Abstract

A perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm (PEComa) in the chest is rare, let alone in the mediastinum and lung.

A 63-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with chest pain for more than 2 months and was found to have an opacity in his mediastinum and lung for 3 weeks. Enhanced chest computed tomography (CT) revealed a mass in both the left upper lobe and central anterior mediastinum. To identify the disease, a CT-guided percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy of the upper left lung lesions was performed. The pathology result was consistent with epithelioid angiomyolipoma/PEComa. After a standard preparation for surgery, the neoplasms in the mediastinum and left lung were resected. The operative findings revealed extensive mediastinal tumor invasion in parts adjacent to the pericardium, including the mediastinal pleura, left pulmonary artery and vein, and phrenic nerve. The left lung tumor had invaded the lung membranes. The final pathologic diagnosis was malignant epithelioid angioleiomyoma in the left upper lung and mediastinum. Later, the mediastinal tumor recurred. The radiography of this case resembles left upper lobe lung cancer with mediastinal lymph node metastasis. Because this tumor lacks fat, the enhanced CT indicated that it was malignant but failed to identify it as a perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm.

This case reminds clinicians that, although most PEComa are benign, some can be malignant. As the radiology indicated, chest PEComas lack fat, which makes their preoperative diagnosis difficult. Therefore, needle biopsy is valuable for a definitive diagnosis.

INTRODUCTION

Perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm (PEComa) is usually a benign mesenchymal neoplasm and occurs in the kidney. The name PEComa is now widely accepted, and the tumor is composed of different proportions of fat, abnormal blood vessels, and smooth muscle cells. The PEComa family includes angiomyolipoma (AML), clear-cell sugar tumor (CCST) of the lung, lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), clear-cell myomelanocytic tumor of the falciform ligament/ligamentum teres and other rare clear-cell tumors.1 Histopathology and immunohistochemistry show that PEComa is composed of distinctive perivascular epithelioid cells.2 Classic AML is a benign tumor composed of mature adipose tissues, spindle and epithelioid smooth muscle cells, and thick-walled blood vessels.3 Epithelioid AML is a special type of AML with potential risk of malignant stromal tumors, which is mainly manifested as epithelioid cell proliferation, and can demonstrate malignant behavior.3 CCSTs are usually benign tumors composed of round to polygonal epithelioid cells, with clear or eosinophilic cytoplasm, and abundant thin-walled blood vessels.1 These tumors are related to the tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), an autosomal dominant genetic disorder due to loss of either TSC1 (chromosome 9q34) or TSC2 (chromosome 16p13), which encodes the hamartin and tuberin proteins, respectively, and may play important regulatory roles in the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway.4–7 Similar genetic mutations have been found in many PEComas, with variable expressions of TSC.8 A small number of PEComas are accompanied by transcription factor E3 (TFE3) gene rearrangements, a finding that has been confirmed and may play a key role during tumorigenesis.9–11 PEComa is also reported at other sites, including the bladder and prostate, uterus, ovary, vulva and vagina, lung, pancreas, and liver.1 As far as we know, only a small number of PEComas occur in the mediastinum or in the lung. To the best of our knowledge, ours is the second case of PEComa occurring in both the mediastinum and the lung. We report for the first time that the level of a tumor marker (cancer antigen 125, CA 125) was increased in mediastinal PEComa, a finding that may help to predict a highly malignant behavior by the tumor.

CONSENT

The patient signed informed consent for the publication of this case report and related images.

CASE REPORT

A 63-year-old man went to our hospital after suffering from chest pain for more than 2 months and was found with an opacity in the mediastinum and the left lung for 3 weeks (Figure 1). His medical history included hepatitis B. The patient had undergone a right nephrectomy at a local hospital 15 years previously, but the case was only characterized as malignancy, without a definite pathologic diagnosis. On physical examination, breath sounds were decreased on the left side and a surgical scar was consistent with a right nephrectomy. Bronchoscopic examination revealed inflammatory lesions in the left bronchial mucosa. Blood routine examination showed a slight anemia (hemoglobin 100 g/L (normal range 131–172), red blood cells 3.35, 10E12/L (normal range 4.09–5.74)), a moderate reduction in the albumin/globulin ratio of 1.2 (normal range 1.5–2.5), and a slight increase in serum CA-125 level (58.8 U/mL (normal range 0.0–35.0)). Other tumor markers, including alpha fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, ferritin, sugar antigen 199, and total prostate specific antigen, were within normal ranges.

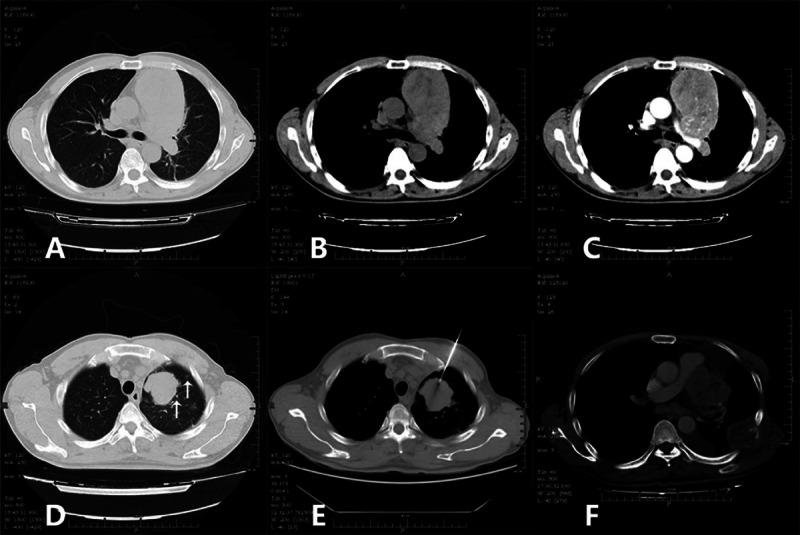

FIGURE 1.

A smoothly edged masses in the left upper lung and the left hilum. .

Plain and contrast enhanced chest computed tomography (CT) revealed a large mass (approximately 6.7 cm × 9.8 cm) with moderately heterogeneous enhancement in the anterior and middle mediastinum and with well-defined margins (Figure 2A–C). The densities of the mediastinal lesions were 21.8–66.8 Hounsfield units (HU) (mean 44.7 HU) in the plain scan and 36.0–79.8 HU (mean 69.4 HU) in the enhanced scan. The main pulmonary artery and the trunk of the left pulmonary artery were compressed, whereas the left upper lobe artery was wrapped in between them. Another mass (approximately 4.2 cm × 4.7 cm) with heterogeneous density and clear edges was also observed in the left upper lobe (Figure 2D), which adhered to the pleura and showed light to medium heterogeneous enhancement. The density of the left upper lung lesion was 26.3–73.5 HU (mean 51.8 HU) in the plain scan and 40.8–96.3 HU (mean 77.2 HU) in the enhanced scan. No fat density or calcification was detected in either type of lesions. A few small nodules were observed around the left pulmonary focus. Swollen lymph nodes were seen in the mediastinum. Based on these CT features, a malignant tumor in the mediastinum and the upper left lung was diagnosed. Emission computed tomography (ECT) revealed a local focal radionuclide concentration in the left sixth rib.

FIGURE 2.

(A) Smoothly edged soft-tissue mass in the anterior and middle mediastinum. (B) Mediastinal mass with slightly heterogeneous density. (C) Abundant blood supply, indicating the blood supply vessels. (D) Mass in the left upper lung found with lobulated edges, clear boundaries, and several small nodules around. (E) The puncture biopsy needle reaches the lesion in the left upper lung. (F) Mass in the mediastinum reoccurs, and the left chest-wall rib is broken, accompanied by a soft-tissue mass.

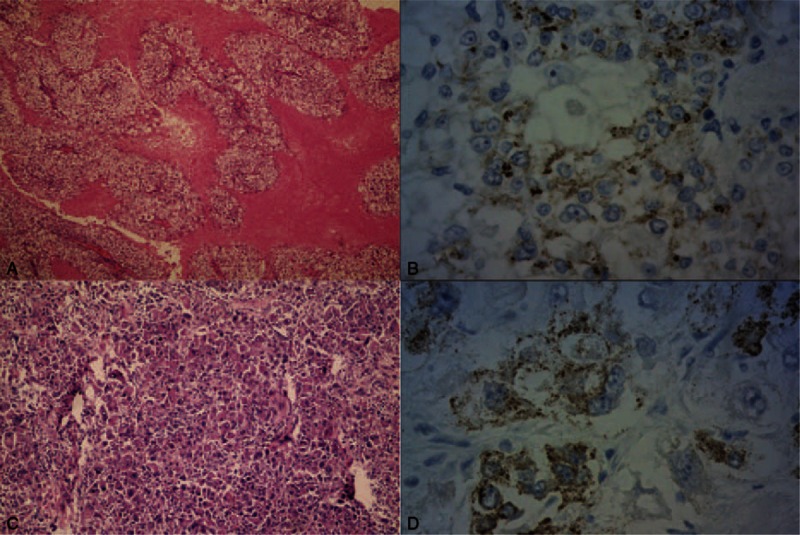

For a definitive diagnosis, CT-guided percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy of the upper left lung lesions was performed (Figure 2E). Histologic examination revealed tumor in soft tissues. The immunohistochemical (IHC) results were consistent with an epithelioid angiomyolipoma/PEComa. On the basis of these comprehensive evaluations, the neoplasms in the mediastinum and the left upper lung were resected. At surgery, masses were located in the anterior mediastinum and the left upper lung, with the tumors widely invading the left phrenic nerve, a part of the pericardium, the mediastinal pleura, and the left pulmonary artery and veins. Abundant necrotic and tumor tissues were found on the sections. The frozen section demonstrated a (mediastinal) epithelioid tumor accompanied by necrosis. As the tumor was partly inseparable from the left pulmonary artery and vein, approximately 5% of the tumor remained in-situ. The left upper pulmonary masses were resected in accordance with the standards of radical resection, the tumor masses were completely removed, and the surgical margins were negative. No metastasis to lymph nodes was seen. The surgical specimens from the mediastinum were reported as follows: tumor tissues composed of thick-wall vessels with distorted tubes, smooth muscular bundles, and fat. Abundant heterotypic cells with red-stained cytoplasm, nuclear atypia, and obvious nucleoli were seen, accompanied by massive hemorrhage and necrosis (Figure 3A). IHC showed that the tumor cells were positive for TFE3, Vimentin and Melan-A; slightly positive for human melanoma black 45 (HMB45) (Figure 3B); and negative for P63, smooth muscle actin (SMA), cytokeratin 7 (CK 7), cluster of differentiation 10 (CD10), paired box gene 8 (PAX8), pan-cytokeratin, Napsin A, and thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1). Based on these findings, the pathologic diagnosis was mediastinal epithelioid AML. Surgical specimens from the left lung masses comprised tumor cells arranged in nest-like lumps with infiltration of the lung membranes. Abundant abnormal vessels were found between tumor cells. Mature fat tissues and massive necrosis were seen in some areas. Cells were found with significant atypia and rich cytoplasm and were stained red. The nuclei were very large with obvious nucleoli (Figure 3C). IHC showed that the tumor cells were positive for Vimentin, HMB45 (Figure 3D), Melan-A, and Ki67 but were negative for pan-cytokeratin, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), and S-100. Based on these findings, the pathologic diagnosis was epithelioid angioleiomyoma in the left upper lung. Three months after surgery, the anterior mediastinal mass recurred, and the metastatic tumor in the left rib had enlarged (Figure 2F). The patient returned to the local hospital but did not undergo radiotherapy due to limited conditions. After a course of chemotherapy (specific chemotherapeutics were unknown), CT re-examination at the local hospital found widespread thoracic metastasis of the tumor and pleural effusion. The patient died of cardiopulmonary failure approximately 7 months after the surgery.

FIGURE 3.

(A) Tumor is composed of smooth muscular bundles and fat and contains many heterotypic cells (hematoxylin-eosin stain, original magnification × 100). (B) Some tumor cells are HMB45-positive (HMB45 stain, original magnification × 400). (C) Tumor cells are arranged like nest lumps and are obviously atypical (hematoxylin-eosin stain, original magnification × 100). (D) Some tumor cells are HMB45-positive (HMB45 stain, original magnification × 400).

DISCUSSION

Only 9 cases of mediastinal PEComa are reported in the English literature.12–20 The age of onset in these cases was 22–62 (mean 43) years, with similar gender distribution.12–20 The lesions occurred mainly in the anterior or the posterior mediastinum, sometimes involving the middle mediastinum.12–20 Approximately half of the patients were asymptomatic, and the tumors were discovered incidentally.12,14,16,17 Some patients suffered from dyspnea, chest pain, and dry cough.13,15,19,20 Some of these symptoms were probably induced by other concomitant diseases. Among patients with mediastinal PEComa, two cases were accompanied by TSC and four cases by LAM; four cases had a history of nephrectomy: three for renal angiomyolipoma and one for an unknown reason.13–15,17,19 Our case was an elderly man without a history of TSC or LAM but with a history of a unilateral nephrectomy. Although the renal disease was unknown, we thought that the kidney lesion was probably associated with the extrarenal PEComa. The main symptom in our case was chest pain. We think that this probably arose from the surgically confirmed lung lesion involving the pleura, rather than the mediastinal lesions. In our case, the pulmonary lesion was only present in the left upper lung, the imaging does not support a metastasis, and the time span is also too long. Moreover, the mediastinal mass was larger than the pulmonary lesion. Furthermore, histopathology does not support the view that the mediastinal lesions originated from a lymph node metastasis. It therefore seems unlikely that the pulmonary and mediastinal lesions are both metastases from the kidney. Based on our findings and interpretation, we hypothesize that malignant epithelioid angiomyolipoma may have a multifocal origin.

As reported, the size of mediastinal PEComa ranges from 1.8 × 2.4 × 3.0 to 5.3 × 10.8 × 23.0 cm3. CT shows that the lesions usually have regular and clear margins and reveals different amounts of fat, but calcification was found in only 1 case.12–20 CT mostly shows slight heterogeneous reinforcement but revealed obvious enhancement only in 1 case, where the lesion had mainly vascular and smooth muscular components.12–18,20 CT in our case showed slight heterogeneous reinforcement but did not detect fat components in the mediastinum or pulmonary masses. As a result, we failed to establish the diagnosis of AML by imaging preoperatively. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings have been reported in 4 cases.13,17,19,20 These included T1 weighted image (T1WI) hyperintensity and slight T2 weight image (T2WI) hyperintensity in 2 cases where fat was present. In the other 2 cases, where fat was not identified, the MRI features included T1WI hypointensity and T2WI hyperintensity.13,17,19,20 Although MRI did not detect fat components in approximately half of the cases, the histopathological examination usually did.12–20 Thus, we recommend a specific MRI sequence, such as the double-echo chemical shift gradient-echo technique, which may help to detect the small amount of fat in a tumor and thus provide clues for preoperative diagnosis and treatment planning. To our knowledge, ours is the first description of the clinical and imaging-based characteristics of a malignant mediastinal PEComa.

CCSTs in the lung are mostly manifested as round-like peripheral nodules with smooth margins and mainly occur in the lower lung, without cavity or calcification.21 One case of mediastinal PEComa had multiple nodules in both lungs, and imaging showed mediastinal lymph node and pulmonary metastasis.14 In contrast, the foci in our case occurred in the left upper lung and were large and lobulated, resembling a lung cancer. Our case was confirmed as a malignant pulmonary PEComa. Until now, only 5 cases of malignant pulmonary PEComa have been reported in the English literature,22–26 mostly affecting older women. Isolated masses were present in 2 cases (size of 3 and 4 cm), and pulmonary masses were present in 2 other cases (5 and 12 cm), accompanied by multi-nodules in both lungs.22–25 Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) of 1 case showed increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake, and calcification correlated with dystrophy was also found in the focus.22 Our case differs from previous cases in 2 respects. First, the intrapulmonary lesion not only invaded the nearby pleura but also showed unilateral intrapulmonary metastatic tumor. We deduce that it was probably the subfocus of the intrapulmonary mass, rather than an intrapulmonary metastatic tumor due to the mediastinal lesion. Second, the bone metastasis present in our case was not reported in previous cases of malignant pulmonary PEComa, though single cases of brain and liver metastasis are reported.25,26 Thus, patients with malignant PEComa require preoperative ECT to exclude the possibility of bone metastases.

Previous mediastinal cases were highly suspected, or diagnosed, by percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy or video-assisted thoracic biopsy.14,15,20 Our case was diagnosed by histological and IHC examination of the intrapulmonary lesion biopsy, indicating that preoperative percutaneous transthoracic needle is effective. Bronchoscopy did not help much for our, or the previous, mediastinal cases.18,20 Isolated mediastinal or intrapulmonary lesions in previous cases were completely resected, without obvious invasion of adjacent organs or tissues.12,13,15–21 In the present case, however, the mediastinal and intrapulmonary lesions both invaded the nearby organs and tissues, involving the left phrenic nerves, mediastinal pleura, large vessels of the left lung, and pericardium. No previous case of mediastinal PEComa was reported with obvious evidence of malignancy, though one case that recurred after 5 years did involve nearby nerves.12,15,20 In our case, the rib metastasis, the short-term recurrence, and the obvious postoperative enlargement of the rib metastasis are obvious evidence of malignancy. We speculate that this malignancy may be associated with a TFE3 gene rearrangement. Our case stained positive for TFE3, and further confirmation was not conducted. Moreover, malignant PEComa may be effectively treated by targeted drugs, which needs to be further investigated.

CONCLUSION

The occurrence of perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasms in the lungs or mediastinum is rare, let alone their occurrence at both sites at the same time. As this case resembles a lung cancer with mediastinal lymph node metastasis, the possibility that these two diseases developed from different primary lesions cannot be ignored. Although CT did not detect fat ingredients, the possibility of perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm could not be excluded by CT. Needle biopsy of a mass in the lungs can facilitate a definitive diagnosis. For malignant pulmonary PEComa, surgical resection is the primary mode of treatment.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AML = angiomyolipoma, CA 125 = cancer antigen 125, CCST = clear-cell sugar tumor, CT = computed tomography, ECT = emission computed tomography, HMB45 = human melanoma black 45, HU = hounsfield units, IHC = immunohistochemical, LAM = lymphangioleiomyomatosis, mTOR = mammalian target of rapamycin, PEComa = perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm, PET/CT = positron emission tomography/computed tomography, T1WI = T1weighted image, T2WI = T2weighted image, TFE3 = transcription factor E3, TSC = tuberous sclerosis complex.

WL, SX, and FC contributed equally to the manuscript.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Martignoni G, Pea M, Reghellin D, et al. PEComas: the past, the present and the future. Virchows Arch 2008; 452:119–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Folpe AL. Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Epstein J, Mertens F. Neoplasms with perivascular epithelioid cell differentiation (PEComas). Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. Series: WHO Classification of Tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2002. 221–222. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JI, et al. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumour of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs. 2004; Lyon: IARC Press, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crino PB, Nathanson KL, Henske EP. The tuberous sclerosis complex. N Engl J Med 2006; 355:1345–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Slegtenhorst M, de Hoogt R, Hermans C, et al. Identification of the tuberous sclerosis gene TSC1 on chromosome 9q34. Science 1997; 277:805–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Chromosome 16 Tuberous Sclerosis Consortium. Identification and characterization of the tuberous sclerosis gene on chromosome 16. Cell 1993; 75:1305–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwiatkowski DJ. Tuberous sclerosis: from tubers to mTOR. Ann Hum Genet 2003; 67:87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henske EP, Neumann HP, Scheithauer BW, et al. Loss of heterozygosity in the tuberous sclerosis (TSC2) region of chromosome band 16p13 occurs in sporadic as well as TSC-associated renal angiomyolipomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 1995; 13:295–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka M, Kato K, Gomi K, et al. Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor with SFPQ/PSF-TFE3 gene fusion in a patient with advanced neuroblastoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2009; 33:1416–1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Argani P, Aulmann S, Illei PB, et al. A distinctive subset of PEComas harbors TFE3 gene fusions. Am J Surg Pathol 2010; 34:1395–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williamson SR, Bunde PJ, Montironi R, et al. Malignant perivascular epithelioid cell neoplasm (PEComa) of the urinary bladder with TFE3 gene rearrangement: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular features. Am J Surg Pathol 2013; 37:1619–1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Candas F, Berber U, Yildizhan A, et al. Anterior mediastinal angiomyolipoma. Ann Thorac Surg 2013; 95:1431–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han WL, Hu J, Rusidanmu A, et al. Chylous pleural effusion caused by mediastinal angiomyolipomas. Chin Med J (Engl) 2012; 125:945–946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morita K, Shida Y, Shinozaki K, et al. Angiomyolipomas of the mediastinum and the lung. J Thorac Imaging 2012; 27:W21–W23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warth A, Herpel E, Schmähl A, et al. Mediastinal angiomyolipomas in a male patient affected by tuberous sclerosis. Eur Respir J 2008; 31:678–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knight CS, Cerfolio RJ, Winokur TS. Angiomyolipoma of the anterior mediastinum. Ann Diagn Pathol 2008; 12:293–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watts KA, Watts JR., Jr Incidental discovery of an anterior mediastinal angiomyolipoma. J Thorac Imaging 2007; 22:180–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amir AM, Zeebregts CJ, Mulder HJ. Anterior mediastinal presentation of a giant angiomyolipoma. Ann Thorac Surg 2004; 78:2161–2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Torigian DA, Kaiser LR, Soma LA, et al. Symptomatic dysrhythmia caused by a posterior mediastinal angiomyolipoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2002; 178:93–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim YH, Kwon NY, Myung NH, et al. A case of mediastinal angiomyolipoma. Korean J Intern Med 2001; 16:277–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang GX, Zhang D, Diao XW, et al. Clear cell tumor of the lung: a case report and literature review. World J Surg Oncol 2013; 11:247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lim HJ, Lee HY, Han J, et al. Uncommon of the uncommon: malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumor of the lung. Korean J Radiol 2013; 14:692–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ye T, Chen H, Hu H, et al. Malignant clear cell sugar tumor of the lung: patient case report. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28:e626–e628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yan B, Yau EX, Petersson F. Clear cell ‘sugar’ tumour of the lung with malignant histological features and melanin pigmentation—the first reported case. Histopathology 2011; 58:498–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parfitt JR, Keith JL, Megyesi JF, et al. Metastatic PEComa to the brain. Acta Neuropathol 2006; 112:349–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sale GE, Kulander BG. ‘Benign’ clear-cell tumor (sugar tumor) of the lung with hepatic metastases ten years after resection of pulmonaryprimary tumor. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1988; 112:1177–1178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]