Abstract

The goal of this study was to systematically review the effects of biliary stenting on postoperative morbidity and mortality of patients with obstructive jaundice. PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and other relevant databases were searched by computer and manually for published and unpublished studies on the impact of preoperative biliary drainage on patients with obstructive jaundice from 2000 to the present day. Two investigators independently selected the studies according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, extracted the data, and assessed the quality of the selected studies. Meta-analysis was performed to compare postoperative morbidity and mortality of patients between the drainage and nondrainage groups.

Compared with the nondrainage group, the overall mortality, overall morbidity, infectious morbidity, incidence of wound infection, intra-abdominal abscess, pancreatic fistulas, bile leak, and delayed gastric emptying in the drainage group were not significantly different. Compared with the nondrainage group, the drainage group had a drainage time of <4 weeks with an increased overall morbidity by 7% to 23%; however, the overall morbidity of the drainage group with a drainage time >4 weeks was not significantly different. Compared with the nondrainage group, the overall mortality of the drainage group using metal stents and plastic stents as internal drainage devices was reduced by 0.5% to 6%, whereas that of the drainage group using plastic stent devices was not significantly different.

In summary, preoperative drainage should be applied selectively. The drainage time should be >4 weeks, and metal stents should be used for internal drainage.

BACKGROUND

The postoperative mortality and postoperative morbidity of patients with malignant obstructive jaundice was 5% to 27% and ∼50%, respectively1,2; in view of high mortality and morbidity, a large number of studies have been carried out to explore the main risk factors. It has been reported that hyperbilirubinemia (serum bilirubin ≥170 μmoL/L) in patients who underwent obstructive jaundice surgery might increase their postoperative morbidity and mortality,3–5 given that hyperbilirubinemia would lead to impairment of liver function, decreased clearance of endotoxin, coagulation disorders, decreased immune function, and impaired gastrointestinal mucosal barrier.6,7 Therefore, to reduce the level of serum bilirubin, preoperative biliary drainage was performed before obstructive jaundice surgery. The earliest report of preoperative biliary drainage was published by Whipple et al8 in 1935, in which 4 weeks after the first operation, a cholecystogastrostomy, pancreatectomy was performed.8 With the development and application of radiological and endoscopic technologies, the methods of minimally invasive preoperative drainage gradually emerged, they include percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography, nasobiliary drainage, and biliary stenting (percutaneous transhepatic approach, endoscopic retrograde approach), with the former serving as external drainage and the latter serving as internal drainage. Despite that preoperative biliary drainage has been suggested to exert positive effect on jaundice patients, such as improving their liver function and reducing the incidence of perioperative complications 9–12; it was not proved to be capable of improving prognosis. The supporters of preoperative biliary drainage have argued that in those studies, the applied drainage methods mostly included external drainage devices or even bypasses, whereas actually, internal drainage adapts better to human physiology; hence, they deemed that those conclusions might be biased.13 Meta-analyses of preoperative biliary drainage have been carried out by several researchers; however, a specific meta-analysis targeting internal drainage has not yet been published. Therefore, the goal of our study was to perform a meta-analysis on the effects of preoperative biliary stenting on patients with obstructive jaundice and to explore the impact of preoperative internal drainage on postoperative complications and mortality.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

All published and unpublished journal articles regarding the impact of preoperative biliary drainage on patients with obstructive jaundice from 2000 to present day were searched by both computer and manual procedures. We followed the meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines for searching and reporting, and this investigation was approved by the ethics committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Guiyang Medical College. Computer research was done in databases of PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and other relevant databases, with the following keywords: preoperative biliary drainage, preoperative biliary stenting, malignant obstructive jaundice, ampullary carcinoma, pancreatic cancer, and pancreaticoduodenectomy. No language restrictions were set; mesh words and free words were combined. In this way, the search range was maximized to select articles that met the requirements.

Methods

Inclusion Criteria

Patients were mainly those suffering from obstructive jaundice; cancer patients who had no local invasion, distant metastasis or cholangitis, and whose condition still allows operations were also included. The primary surgical method was pancreaticoduodenectomy. The intervention measure was biliary stent placement for internal drainage, and there were no restrictions regarding the surgical approach for stent placement, drainage time, or stent material. The outcomes included postoperative morbidity and/or postoperative mortality. The hypotheses of all the included studies were similar.

Exclusion Criteria

The patient had local invasion or distant metastasis, or concomitant cholangitis; the drainage method was external drainage or a combination of external and internal; the outcomes did not include postoperative complications and mortality; repeated reports; the design was flawed, and the quality of the study was poor.

Literature Screening, Quality Assessment, and Data Extraction

The literature was screened by 2 investigators independently, the quality of the studies were assessed afterwards based on the quality assessment criteria recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews (Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: version 5.0.1. Cochrane Collaboration, 2008), namely whether the included studies involved randomly assigned groups, allocation concealment, blind design, description of dropped follow-ups, intention to treat (ITT) analysis on dropped follow-ups, and consistent baselines. The data in all studies were then extracted before a cross-check of the results. If there was disagreement, a discussion or consultation with a third party was needed.

Statistical Analysis

Meta-analysis was performed on RevMan 5.2 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK) software provided by the Cochrane Collaboration. A χ2 test was performed to test the heterogeneity between target studies. If there was no significant heterogeneity (P ≥ 0.05), the fixed effect model was applied for follow-up analysis; if there was significant heterogeneity (P < 0.05), the random effects model was applied. The outcome variables were the ratio of postoperative morbidity and mortality of the group with preoperative drainage to that of the group without preoperative drainage, that is, the corresponding odds ratio (OR). STATA 12.0 (Stata, StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) software was used to analyze publication bias through Begg test. Subgroup analysis was used to evaluate the effect of drainage material and time to the results.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Included Studies and Quality Assessment

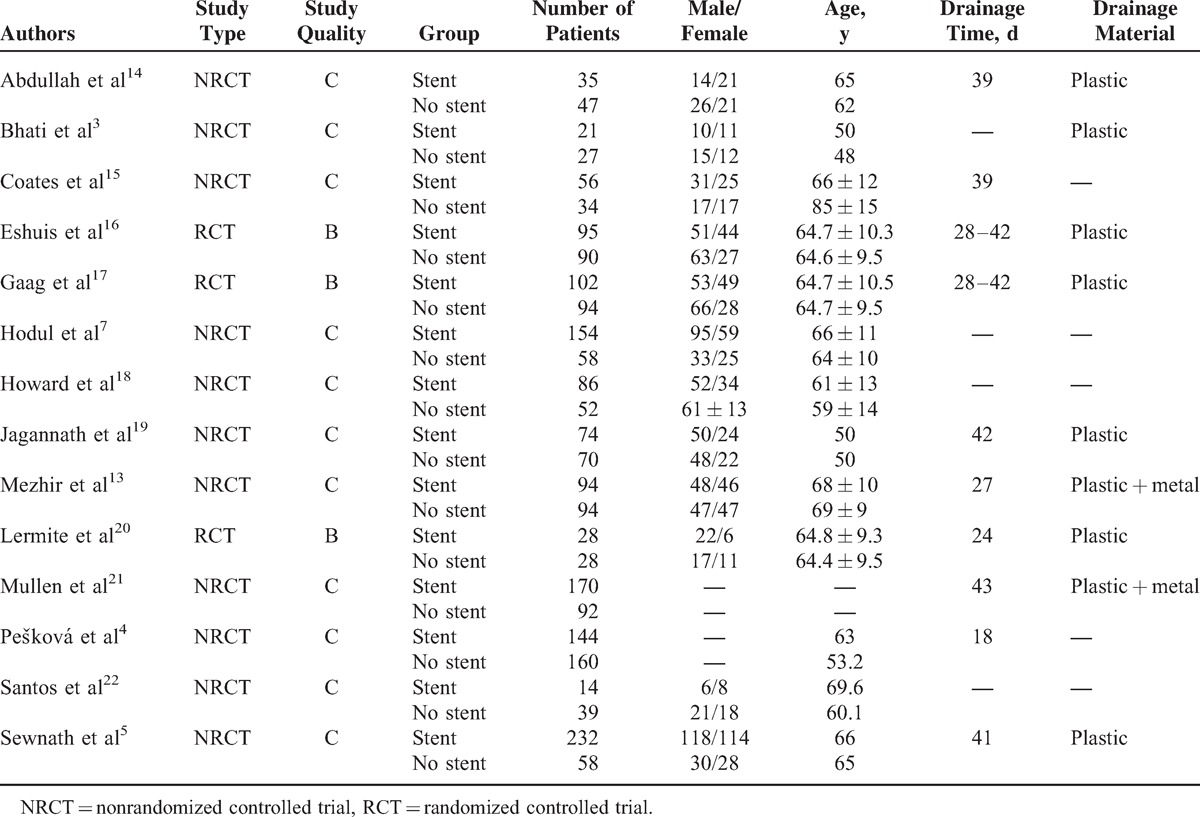

According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 14 articles were included in the present study. The total number of patients was 2248, of whom 1305 had undergone preoperative drainage and 943 had not. Among the 14 articles, 11 (quality assessment for class C) of them were retrospective cohort studies except for 3 (quality assessment for class B) randomized controlled trials. Two studies out of the 14 involved pancreatic cancer patients and 1 study involved an ampullary cancer patient; the other studies were all about patients with obstructive jaundice who once underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy. In 1/14 articles, patients who had preoperative drainage were divided into 2 subgroups based on the stent material, that is, metal or plastic, to compare the effects of stent material on the outcome; in another article, the drainage group was divided into 3 subgroups based on the preoperative serum bilirubin levels that were low, medium, or high. The result of quality assessment of the included literature is shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Patient Information of the Included Studies

Meta-Analysis

Overall Mortality

All studies reported the overall mortality. There was no significant heterogeneity among the studies (P = 0.63); therefore, the fixed effects model was used. The result of meta-analysis showed that the overall mortality did not differ significantly between the 2 groups (OR = 0.74, 95% confidence interval [CI] [0.52, 1.05]) (see Figure 1 A).

FIGURE 1.

(A) Overall mortality, (B) overall morbidity, (C) infectious morbidity, (D) wound infection, (E) intra-abdominal abscess, (F) pancreatic fistula, (G) bile leak, (H) delayed gastric emptying.

Overall Morbidity

Twelve studies reported the overall morbidity. There was significant heterogeneity between the studies (P = 0.002), and therefore, the random effects model was used. The meta-analysis showed that the overall morbidity did not differ significantly between the 2 groups (OR = 1.11, 95% CI [0.76, 1.64]) (see Figure 1 B).

Incidence of Infectious Morbidity

Seven studies reported the incidence of infectious morbidity. There was significant heterogeneity among the studies (P < 0.001), and therefore, the random effects model was used. The meta-analysis showed that the incidence of infectious morbidity did not differ significantly between the 2 groups (OR = 1.62, 95% CI [0.70, 3.77]) (see Figure 1 C).

Incidence of Wound Infection

Ten studies reported the incidence of wound infection. There was significant heterogeneity among the studies (P = 0.009), and therefore, the random effects model was used. The meta-analysis showed that the incidence of wound infection morbidity did not differ significantly between the 2 groups (OR = 1.46, 95% CI [0.69, 3.10]) (see Figure 1 D).

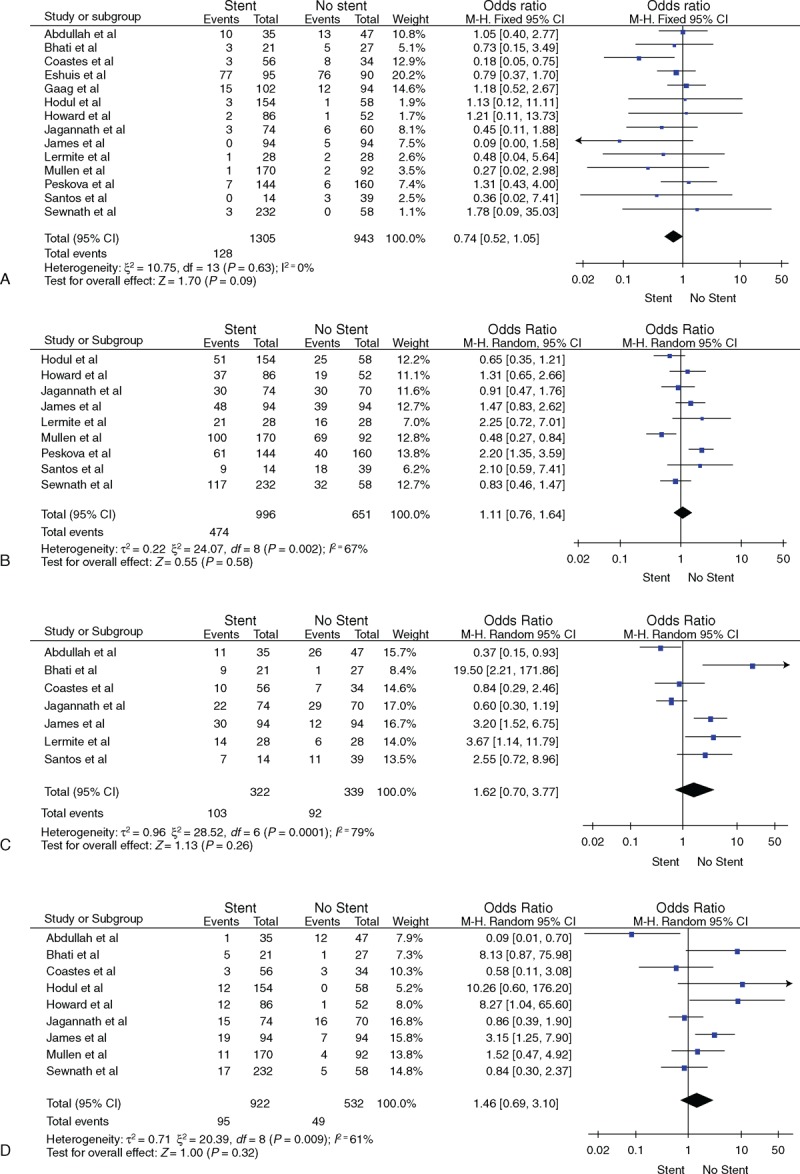

Incidence of Intra-abdominal Abscess

Seven studies reported the incidence of intra-abdominal abscess. There was no significant heterogeneity among the studies (P = 0.04), and therefore, the fixed effects model was used. The meta-analysis showed that the incidence of intra-abdominal abscess did not differ significantly between the 2 groups (OR = 0.77, 95% CI [0.30, 1.93]) (see Figure 1 E).

Incidence of Pancreatic Fistula

Six studies reported the incidence of pancreatic fistula. There was no significant heterogeneity among the studies (P = 0.44), and therefore, the fixed effects model was used. The meta-analysis showed that the incidence of pancreatic fistula did not differ significantly between the 2 groups (OR = 0.95, 95% CI [0.56, 1.61]) (see Figure 1 F).

Incidence of Bile Leak

Six studies reported the incidence of pancreatic bile leak. There was no significant heterogeneity among the studies (P = 0.79), and therefore, the fixed effects model was used. The meta-analysis showed that the incidence of bile leak did not differ significantly between the 2 groups (OR = 1.61, 95% CI [0.74, 3.51]) (see Figure 1 G).

Incidence of Delayed Gastric Emptying

Eight studies reported the incidence of delayed gastric emptying. There was no significant heterogeneity among the studies (P = 0.82), and therefore, the fixed effects model was used. The meta-analysis showed that the incidence of delayed gastric emptying did not differ significantly between the 2 groups (OR = 1.07, 95% CI [0.75, 1.54]) (see Figure 1 H).

Publication Bias Analysis

A funnel plot was applied for publication bias analysis (Figure 2), which resulted in a symmetric inverted funnel shape in all plots. The results of Begg test indicate that there were no publication bias in all studies (P > 0.252).

FIGURE 1 (Continued).

(A) Overall mortality, (B) overall morbidity, (C) infectious morbidity, (D) wound infection, (E) intra-abdominal abscess, (F) pancreatic fistula, (G) bile leak, (H) delayed gastric emptying.

Subgroup Analysis

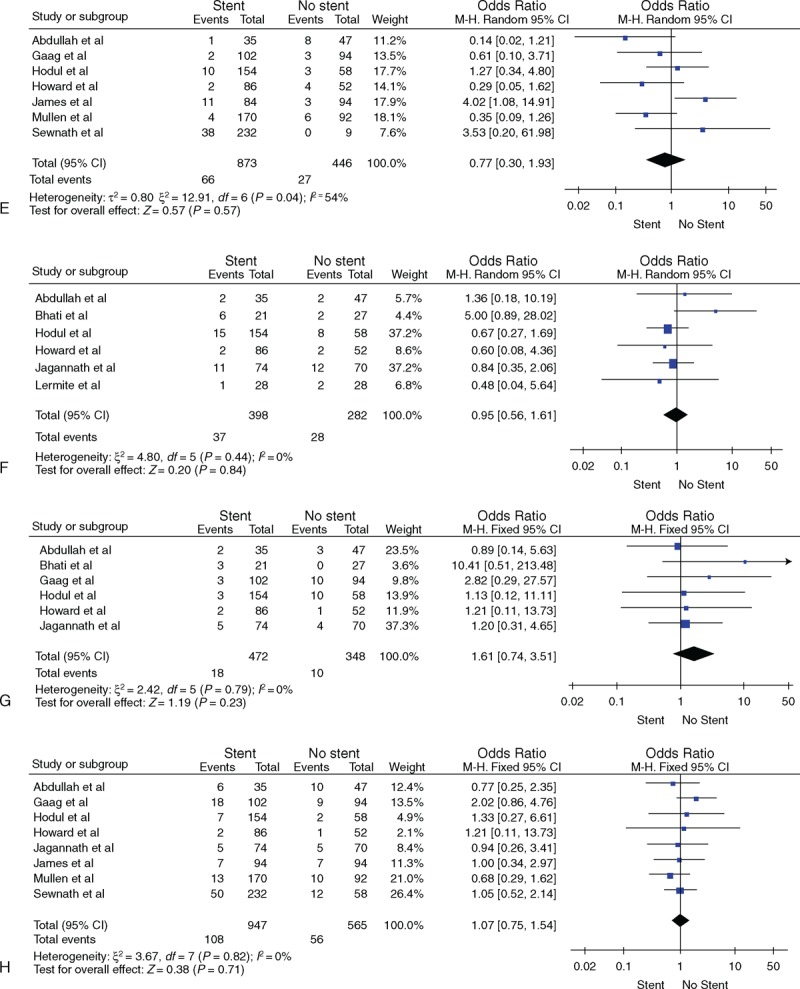

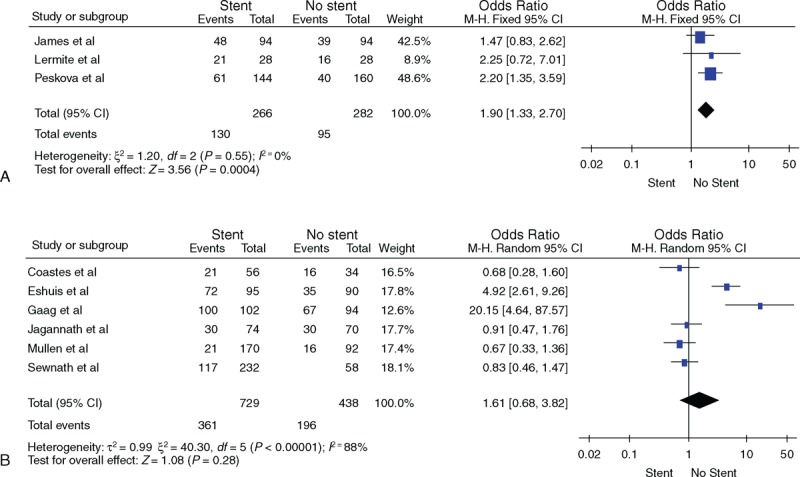

Group Analysis Based on Drainage Time

Ten studies reported the duration of preoperative drainage, including 3 studies discussing a duration of <4 weeks (group I) and 7 discussing a duration of >4 weeks (group II). As shown in Figure 3, the overall mortalities of groups I and II were (OR = 0.66, 95% CI [0.28, 1.58]) and (OR = 0.75, 95% CI [0.50, 1.13]), respectively, which indicate that they did not differ from each other significantly. Besides, in groups of I and II, the overall morbidities were (OR = 1.90, 95% CI [1.33, 2.70]) and (OR = 1.61, 95% CI [0.68, 3.82]), respectively. When compared with nondrainage patients of group I, the overall morbidity of drainage patients increased by 7% to 23%, which was greater than that of nondrainage patients; whereas, the overall morbidity of group II was not obviously different between drainage and nondrainage patients. We speculated that longer drainage duration, for instance, >4 weeks, might help reduce the overall morbidity.

FIGURE 2.

(A) Overall mortality, (B) overall morbidity, (C) infectious morbidity, (D) wound infection, (E) intra-abdominal abscess, (F) pancreatic fistula, (G) bile leak, (H) delayed gastric emptying.

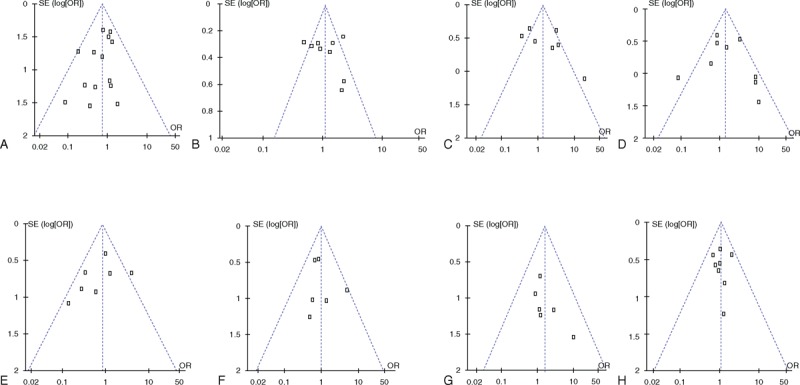

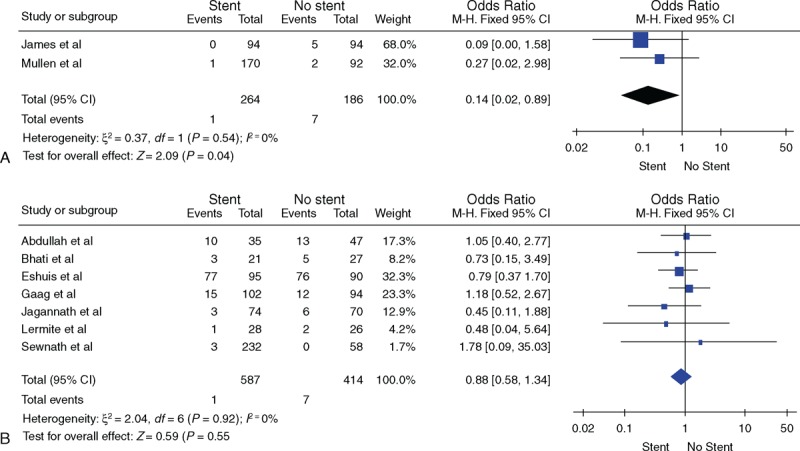

Group Analysis Based on Stent Material

Nine studies discussed the stent material (metal/plastic). In 7 studies, plastic stents were used and in the remaining 2, both metal and plastic stents were used. As shown in Figure 4, the overall mortalities of plastic and metal–plastic group were (OR = 0.88, 95% CI [0.58, 1.34]) and (OR = 0.14, 95% CI [0.02, 0.89]), respectively, and the overall morbidities of the 2 groups were (OR = 2.48, 95% CI [0.91, 6.77]) and (OR = 1.16, 95% CI [0.72, 1.86]), respectively. The overall morbidity was not affected by the stent material.

FIGURE 3.

(A) Comparison of total morbidity between the nondrainage and drainage groups with drainage times <4 weeks. (B) Comparison of total morbidity between the nondrainage and drainage groups with drainage time >4 weeks.

FIGURE 4.

(A) Comparison of total mortality between the nondrainage and drainage groups using plastic and metal as stent material. (B) Comparison of total mortality between the nondrainage and drainage groups using plastic as stent material.

When compared with the nondrainage group, the overall mortality of the drainage group using metal–plastic stents was reduced by 0.5% to 6%; yet, the rates of the drainage group using plastic stents only were not significantly different. We conjectured that metal stents could reduce the overall mortality and possibly are superior to plastic ones.

DISCUSSION

It still remains controversial whether to perform preoperative biliary drainage on obstructive jaundice patients with indications for surgery routinely.4,13,23 Previous retrospective and prospective randomized controlled trials have drawn different conclusions. Some studies have reported that preoperative biliary drainage could reduce the length of a hospital stay, the postoperative infection rate, renal damage, and bleeding.24–26 Lygidakis et al27 suggested that preoperative biliary drainage could reduce the pressure within the biliary tract, improve liver function, and reduce perioperative bleeding and postoperative complications. Abdullah et al14 reported that preoperative biliary drainage could reduce the rate of wound infections and did not affect the overall mortality. However, some studies declared that preoperative biliary drainage can increase the chances of biliary infection and infectious complications.3,19,20 Pešková et al4 indicated that preoperative biliary drainage could also increase the overall morbidity. Studies have shown that many severe complications were caused by improper drainage.17 Despite the improvements in drainage technology, surgical conditions, and perioperative care, it is still unclear whether the outcome of preoperative drainage has caused any improvements. Hence, in the current study, articles from the past decade were selected for meta-analysis.

Preoperative drainage methods include external and internal drainage. External drainage can lead to insufficient bile in the intestines, and thus, weakened inhibition of intestinal bacteria causing endotoxemia.5 It may also cause malnutrition because of lipid malabsorption and fluid balance disorders because of bile loss. In contrast, internal drainage can significantly improve these drawbacks of external drainage. Materials used for internal drainage include plastic and metal stents. Plastic stents are inexpensive and easy to operate for repeated placement; however, its major disadvantage is the presence of 3 to 6 internal obstructions,28 which may result in recurrence of jaundice and increase the incidence of cholangitis.29–31 Compared with plastic stents, metal stents have a larger diameter when expanded, and the expansion time is notably longer.32–34 Wasan et al35 showed that metal stents could reduce the occurrence of cholangitis and intraoperative and postoperative complications. However, metal stents may also become obstructed through tumor ingrowth or overgrowth.36,37 We performed a meta-analysis on drainage subgroups using different stent materials and found that the overall mortality and morbidity of the subgroups using plastic stents were not significantly different from the nondrainage group. Compared with the nondrainage group, the overall morbidity of the drainage subgroup using plastic and metal stents was not significantly different, yet its overall mortality was significantly lower. Compared with using plastic stents only, the use of metal and plastic stents can reduce the overall mortality. This suggests that compared with plastic stents, metal stents can reduce mortality. However, there were only 2 studies that have used plastic and metal stents for internal drainage. The small number of available studies makes this conclusion unreliable.

Drainage time is still a rather controversial issue. The supporters of preoperative biliary drainage believe that the reason why preoperative biliary drainage did not have any benefits in some cases was that the drainage time was too short. As liver function recovery requires 4 to 6 weeks, even if the bilirubin level may have returned to normal prior to 4 weeks, the drainage time should last 4 to 6 weeks.4,20 However, an overly long drainage time may increase infectious morbidity. In the present study, a meta-analysis on studies with drainage times ≥4 weeks showed that the overall mortality and morbidity were not significantly different from that of the nondrainage group. A meta-analysis on studies with drainage times <4 weeks showed that the overall mortality was not significantly different from that of the nondrainage group, yet the overall morbidity of the former group was significantly higher than that of the latter group. This suggests that a drainage time ≥4 weeks can reduce overall morbidity compared with a drainage time <4 weeks. However, studies with drainage times ≥4 weeks showed relatively large heterogeneity. Sensitivity analysis revealed that the results obtained from the fixed effects and random effects models were different. Hence, this conclusion is not very reliable.

Thus, we believe that preoperative biliary drainage should not be routinely applied. However, for patients with severe jaundice (serum bilirubin level ≥150 μm/L), concomitant cholangitis, or severe malnutrition and patients who need a relatively long preoperative assessment and wait for a relatively long time before the surgery, preoperative drainage may be selectively applied.38 We suggest that the drainage time should >4 weeks, and metal stents should be used for drainage.

This study has limitations. First, the quality of the included studies was not high. Second, there was a relatively large heterogeneity among different studies regarding the comparison of overall morbidity, infectious morbidity, and wound infection, and the results obtained from using the fixed effects and random effects models were different, thereby leading to unreliable conclusions. The main cause of the heterogeneity was that different studies defined the complications differently, and the evaluation criteria were different. Hence, future large-scale, large-sample, multicenter randomized controlled trials using standardized assessment indicators are still needed.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval, MOOSE = meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology, NRCT = nonrandomized controlled trial, OR = odds ratio.

CS and GY contributed equally to this work.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lai EC, Chu KM, Lo CY, et al. Surgery for malignant obstructive jaundice: analysis of mortality. Surgery 1992; 112:891–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karsten T, Allema J, Reinders M, et al. Preoperative biliary drainage, colonisation of bile and postoperative complications in patients with tumours of the pancreatic head: a retrospective analysis of 241 consecutive patients. Eur J Surg 1996; 162:881–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhati CS, Kubal C, Sihag PK, et al. Effect of preoperative biliary drainage on outcome of classical pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13:1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pešková M, Gürlich R. Preoperative biliary drainage before pancreatoduodenectomy in patients with obstructive jaundice. Eur Surg 2005; 37:331–335. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sewnath ME, Birjmohun RS, Rauws EA, et al. The effect of preoperative biliary drainage on postoperative complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg 2001; 192:726–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qiu Y-D, Bai J-L, Xu F-G, et al. Effect of preoperative biliary drainage on malignant obstructive jaundice: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17:391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hodul P, Creech S, Pickleman J, et al. The effect of preoperative biliary stenting on postoperative complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Am J Surg 2003; 186:420–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whipple AO, Parsons WB, Mullins CR. Treatment of carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater. Ann Surg 1935; 102:763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armstrong C, Dixon J, Taylor T, et al. Surgical experience of deeply jaundiced patients with bile duct obstruction. Br J Surg 1984; 71:234–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dixon J, Armstrong C, Duffy S, et al. Factors affecting morbidity and mortality after surgery for obstructive jaundice: a review of 373 patients. Gut 1983; 24:845–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kimmings AN, van Deventer SJ, Obertop H, et al. Inflammatory and immunologic effects of obstructive jaundice: pathogenesis and treatment. J Am Coll Surg 1995; 181:567–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Padillo J, Puente J, Gómez M, et al. Improved cardiac function in patients with obstructive jaundice after internal biliary drainage: hemodynamic and hormonal assessment. Ann Surg 2001; 234:652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mezhir JJ, Brennan MF, Baser RE, et al. A matched case–control study of preoperative biliary drainage in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma: routine drainage is not justified. J Gastrointest Surg 2009; 13:2163–2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdullah SA, Gupta T, Jaafar KA, et al. Ampullary carcinoma: effect of preoperative biliary drainage on surgical outcome. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15:2908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coates JM, Beal SH, Russo JE, et al. Negligible effect of selective preoperative biliary drainage on perioperative resuscitation, morbidity, and mortality in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. Arch Surg 2009; 144:841–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eshuis WJ, van der Gaag NA, Rauws EA, et al. Therapeutic delay and survival after surgery for cancer of the pancreatic head with or without preoperative biliary drainage. Ann Surg 2010; 252:840–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Gaag NA, Rauws EA, van Eijck CH, et al. Preoperative biliary drainage for cancer of the head of the pancreas. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howard TJ, Yu J, Greene RB, et al. Influence of bactibilia after preoperative biliary stenting on postoperative infectious complications. J Gastrointest Surg 2006; 10:523–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jagannath P, Dhir V, Shrikhande S, et al. Effect of preoperative biliary stenting on immediate outcome after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg 2005; 92:356–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lermite E, Pessaux P, Teyssedou C, et al. Effect of preoperative endoscopic biliary drainage on infectious morbidity after pancreatoduodenectomy: a case–control study. Am J Surg 2008; 195:442–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mullen JT, Lee JH, Gomez HF, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy after placement of endobiliary metal stents. J Gastrointest Surg 2005; 9:1094–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.dos Santos JS, Júnior WS, Modena J, et al. Effect of preoperative endoscopic decompression on malignant biliary obstruction and postoperative infection. Hepatogastroenterology 2005; 52:45–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith RA, Dajani K, Dodd S, et al. Preoperative resolution of jaundice following biliary stenting predicts more favourable early survival in resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2008; 15:3138–3146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Denning DA, Ellison EC, Carey LC. Preoperative percutaneous transhepatic biliary decompression lowers operative morbidity in patients with obstructive jaundice. Am J Surg 1981; 141:61–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gundry SR, Strodel WE, Knol JA, et al. Efficacy of preoperative biliary tract decompression in patients with obstructive jaundice. Arch Surg 1984; 119:703–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marcus SG, Dobryansky M, Shamamian P, et al. Endoscopic biliary drainage before pancreaticoduodenectomy for periampullary malignancies. J Clin Gastroenterol 1998; 26:125–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lygidakis N, Van der Heyde M, Lubbers M. Evaluation of preoperative biliary drainage in the surgical management of pancreatic head carcinoma. Acta Chir Scand 1986; 153:665–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levy MJ, Baron TH, Gostout CJ, et al. Palliation of malignant extrahepatic biliary obstruction with plastic versus expandable metal stents: an evidence-based approach. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 2:273–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cipolletta L, Rotondano G, Marmo R, et al. Endoscopic palliation of malignant obstructive jaundice: an evidence-based review. Dig Liver Dis 2007; 39:375–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Costamagna G, Pandolfi M. Endoscopic stenting for biliary and pancreatic malignancies. J Clin Gastroenterol 2004; 38:59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siddiqui AA, Sreenarasimhaiah J, Lara LF, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided transduodenal placement of a fully covered metal stent for palliative biliary drainage in patients with malignant biliary obstruction. Surg Endosc 2011; 25:549–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davids PH, Groen AK, Rauws E, et al. Randomised trial of self-expanding metal stents versus polyethylene stents for distal malignant biliary obstruction. Lancet 1992; 340:1488–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Knyrim K, Wagner H, Pausch J, et al. A prospective, randomized, controlled trial of metal stents for malignant obstruction of the common bile duct. Endoscopy 1993; 25:207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prat F, Chapat O, Ducot B, et al. A randomized trial of endoscopic drainage methods for inoperable malignant strictures of the common bile duct. Gastrointest Endosc 1998; 47:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wasan SM, Ross WA, Staerkel GA, et al. Use of expandable metallic biliary stents in resectable pancreatic cancer. Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100:2056–2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fockens P, Waxman I, Davids P, et al. Early recurrence of obstructive jaundice after placement of a self-expanding metal endoprosthesis. Endoscopy 1992; 24:428–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cremer M, Deviere J, Sugai B, et al. Expandable biliary metal stents for malignancies: endoscopic insertion and diathermic cleaning for tumor ingrowth. Gastrointest Endosc 1990; 36:451–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakeeb A, Pitt H. The role of preoperative biliary decompression in obstructive jaundice. Hepatogastroenterology 1994; 42:332–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]