Abstract

Spastic scapular dyskinesia after stroke is rare, which causes impaired shoulder active range of motion (ROM). To date, there has been no report about botulinum toxin injection to spastic periscapular muscles. This study presents botulinum toxin A injection for management of spastic periscapular muscles after stroke in 2 cases.

This is a retrospective study of 2 cases of spastic scapular dyskinesia after stroke. Spasticity of periscapular muscles including rhomboid and lower trapezius was diagnosed by physical examination and needle electromyographic study. Botulinum toxin was injected into the spastic periscapular muscles under ultrasound imaging guidance.

During the 3-week follow-up visit after injection, both patients showed increased shoulder active ROM, without any sign of scapular destabilization.

The results suggest that botulinum toxin injection to spastic periscapular muscles can increase shoulder active ROM without causing scapular destabilization in patients with poststroke spastic scapular dyskinesia.

INTRODUCTION

Spasticity is a common problem in poststroke hemiplegic patients. Typical clinical presentation of poststroke spasticity in the upper extremity includes shoulder adduction and internal rotation, elbow flexion, forearm pronation, and wrist/finger flexion.1 Botulinum toxin injection has been commonly used for focal spasticity management after stroke.2,3 Botulinum toxin effectively blocks acetycholine receptors presynaptically to decrease the release of acetylcholine at neuromuscular junctions,4 resulting in muscle relaxation, thus spasticity reduction. The effect usually starts 2 to 3 days after injection, and reaches its peak at about 3 weeks, and gradually wears off in 3 months. Side effects of botulinum toxin injection are usually rare. One possible side effect (also treatment effect) is muscle weakness.2,3 Focal spasticity in periscapular muscles, such as rhomboids muscles, is rare. To date, no known study has reported botulinum toxin injection to these muscles for spasticity management. These periscapular muscles play an important role in scapular stabilization. One concern is that scapular destabilization from muscle weakness after botulinum toxin injection might jeopardize shoulder movement.

Recent research findings have shown that there exists sustained spontaneous motor unit firing in spastic muscles in stroke patients at rest.5–7 These spontaneous activities increase during voluntary activation of spastic muscles6 and maintain at a higher level after voluntary activation.7 Injection to a spastic muscle is reported to result in reduction of spontaneous motor unit firing and improved active movement and control of its antagonist.3,4,8,9 It follows that botulinum toxin injection to periscapular muscles for focal spasticity management could improve active movement of the shoulder joint. Here are 2 such cases. This retrospective study was approved by the University of Texas Health Science Center—Houston ethics committee, and both patients provided written informed consent prior to botulinum toxin injection.

CASE DESCRIPTION

Case 1

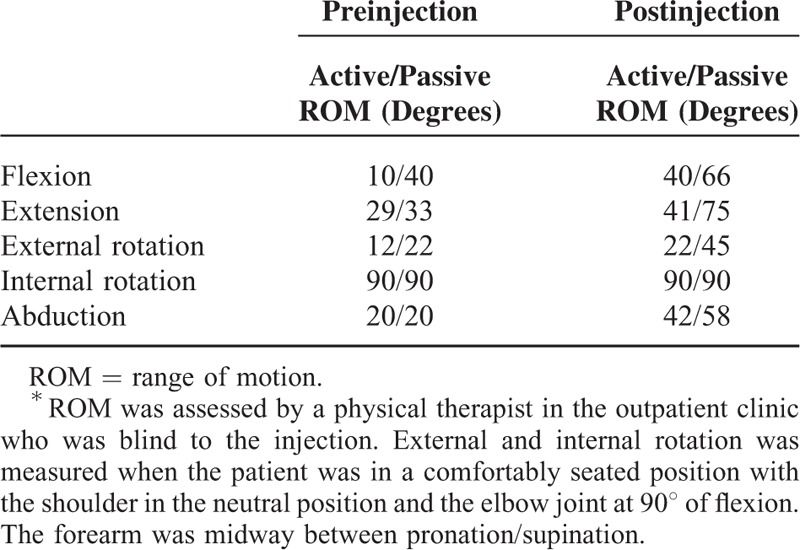

An 86-year-old right-handed woman with past medical history significant for hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and coronary artery disease sustained a hemorrhagic stroke in superior left pons, resulting in right spastic hemiplegia. She received comprehensive inpatient rehabilitation and continued to have outpatient physical therapy (PT) and occupational therapy (OT) for another 2 months after discharge. She presented at 10 months poststroke with right hemiparesis. In her right upper extremity, she had difficulty anteriorly flexing her shoulder, but with adequate active range of motion (ROM) in right elbow/wrist/fingers. She denied history of right shoulder pain, subacromial impingement syndrome, or capsulitis. The patient reported that she could not reach her mouth with her right hand. On physical examination, her right shoulder active and passive ROM was decreased, especially in flexion and abduction (see Table 1). Passive and active ROMs were within normal limits in her right elbow, wrist, hand, and fingers. Muscle strength was 4/5 for shoulder flexors/adductors/rotators and elbow flexors, and 4+/5 for wrist and finger flexors/extensors. She had mild scoliosis. Her right scapula was found to be more superiorly and medially positioned than left side. Except for mild spasticity in her right elbow flexors (Modified Ashworth Scale 1), muscle tone was within normal limits in other muscles in the upper extremity. Right rhomboid muscles were felt tight, as compared to the left side and other periscapular muscles. No focal tenderness or taut band was found in the rhomboids muscle. Needle electromyographic (EMG) study with Clavis (Natus Medical Inc, San Carlos, CA, USA) showed spontaneous activity in right rhomboid at rest, and the activity (loudness) increased during flexion and abduction of right shoulder joint. No spontaneous activity was found in rhomboids muscles on the left side. A total of 100 units of onabotulinum toxin A was injected into the right rhomboid muscles (3 sites) under guidance of ultrasound imaging. She did not receive any therapy after injection. During the 3-week follow-up visit after injection, her right shoulder ROM was significantly improved (Table 1). She was able to reach her mouth with her right hand.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of Active/Passive ROM of the Shoulder Joint Complex Between Preinjection and Postinjection of Onabotulinum Toxin A Into the Rhomboid Muscles∗

Case 2

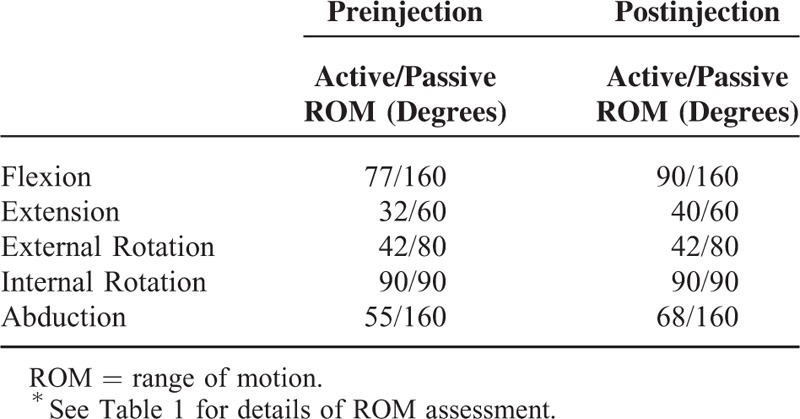

This was a 53-year-old right-handed woman with a history of obesity (125 kg, body mass index: 48), hypertension, and cerebral aneurysm and left middle cerebral artery (MCA) infarct. Patient developed a left MCA infarct after stenting of the left MCA aneurysm 2 years ago with residual right hemiparesis for which she was hospitalized for inpatient rehabilitation. She was then discharged with continuing outpatient PT, OT, and speech therapy. Patient has recovered very well. She was able to ambulate without any assistance. Two year after stroke, she was referred for evaluation and management of pain in her right upper extremity. The patient reported that it was difficult for her to elevate her right shoulder and reach her mouth consistently, and that her right hand/fingers were mildly swollen and sensitive to touch. She denied history of injury, impingement syndrome or capsulitis in her right shoulder. On examination, the right scapula was found to be medially and superiorly positioned as compared to the left scapula. There was diffuse tenderness to palpation, more on right trapezius and rhomboids muscles. Her right hand and fingers were mildly and diffusely swollen and were sensitive to touch. Muscle strength was 4+/5 in right upper extremity. Passive ROM was adequate and impingement signs were negative in her right shoulder (Table 2). Active ROM was normal in her right elbow, wrist, and fingers. Muscle tone was within normal limits in shoulder adductors and internal rotators as well as elbow, wrist, and finger flexors or extensors; however, there was increased tightness in right trapezius and rhomboids muscles. No focal tenderness or taut band was found in these muscles. Needle EMG study with Clavis showed spontaneous activity (noise) in right rhomboid and lower trapezius muscles at rest, and the activity increased during flexion or abduction of the right shoulder. No spontaneous motor unit activity was detected on the left side. She received 200 units of botulinum toxin injection to those 2 muscles (100 units each) under ultrasound guidance. She was also prescribed gabapentin 200 mg three times a day by mouth for neuropathic pain. During follow-up 3 weeks after injection, pain in her right upper extremity was much improved and active ROM of her right shoulder increased. She was able to move her right shoulder more and was able to engage her right arm/hand for eating (Table 2). She did not receive any therapy before and after injection.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of Active/Passive ROM of the Shoulder Joint Complex Between Preinjection and Postinjection of Botulinum Toxin Into Rhomboid and Lower Trapezius Muscles∗

DISCUSSION

We reported 2 cases with focal spasticity in periscapular (rhomboids) muscles after stroke. Both had adequate elbow/wrist/hand movements. Spasticity in periscapular muscles was diagnosed based on physical examination and needle EMG examination. Botulinum toxin injection to rhomboids muscles with subsequent improvement in active and passive ROM of shoulder joint further supports the diagnosis. The positive clinical outcome suggests that botulinum toxin injection is not likely to cause scapular destabilization in these patients with spastic rhomboids. In contrast, botulinum toxin injection to another perioscapular muscle (the upper trapezius) was reported to result in scapular dyskinesis in a patient without neurological impairment. Abbott and Richardson10 reported a case of a 49-year-old woman with a 25-year history of cervical and upper thoracic myofascial pain secondary to a motor vehicle collision. Patient's symptoms were refractory to a wide array of traditional treatments. She received 3 sets of botulinum toxin injection into the upper trapezius. Her myofascial pain significantly improved but unfortunately she developed subacromial impingement syndrome. The contrasting clinical outcome is likely mediated by different underlying mechanisms.

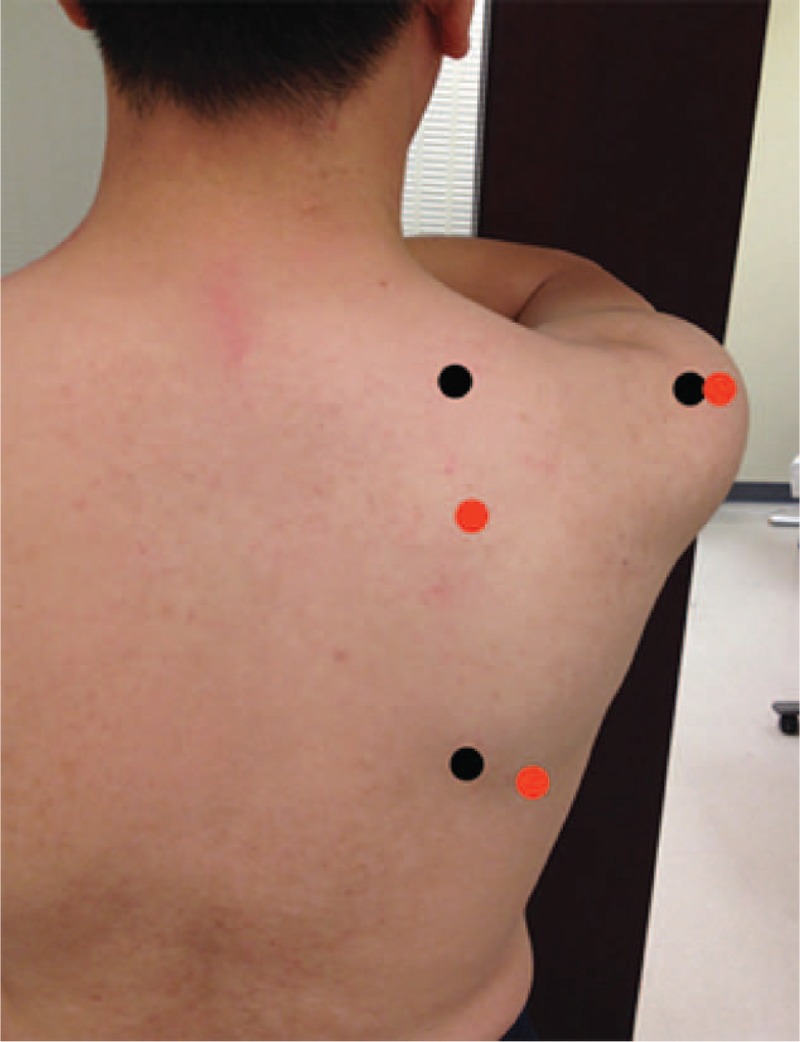

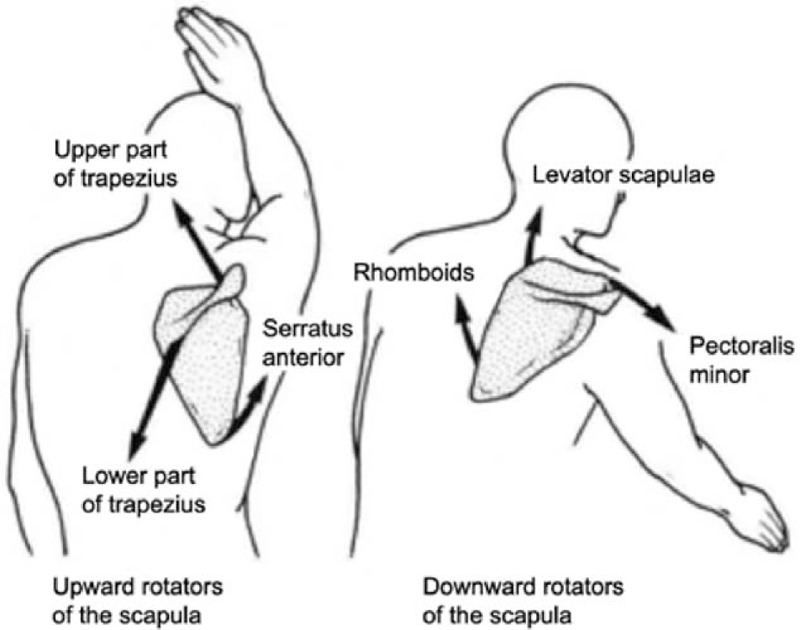

The shoulder joint is a joint complex made of glenohumeral (GH), acromioclavicular, scapulothoracic, and sternoclavicular joints. It has long been clinically observed that the scapula over the thorax is finely coordinated with rotation at the GH joint (“scapula-humeral rhythm”).11,12 As shown in Figure 1, the position of the scapula changes (from the black dots to the red dots) following the scapula-humeral rhythm when the GH joint moves from the neutral position to anterior flexion of 90°. The periscapular muscles are important for the scapula-humeral rhythm because they ensure proper positioning of the scapula in conjunction with the GH joint motion. The lateral (upward) scapular rotation mainly coordinates with shoulder flexion and elevation above head, and shoulder abduction, which is achieved via a force coupling comprised of the upper and lower trapezius and the serratus anterior. In contrast, major muscles contributing to scapular medial rotation consists of rhomboids, levator scapulae, and pectoralis minor muscles (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

Lateral (upward) rotation of scapular motion during 90° anterior flexion of the glenohumeral joint (outlined by red dots) from the neutral position (black dots). Three dots correspond to root of the spine of the scapula (medial upper), inferior angle of the scapula (inferior), and posteroinferior angle of acromion (lateral).

FIGURE 2.

Coordination motion of scapula with shoulder anteflexion and elevated above head.

Based on the above scapular kinematics and the functional role of the periscapular muscles, it is inferred that altered activation of one or more periscapular muscles will disturb the equilibrium between force couples that stabilize the scapula. For example, isolated weakening of the upper trapezius muscle is caused by repeated botulinum injection in a case reported by Abbott and Richardson.10 This subsequently results in increased medial rotation of the scapula (Figure 2). Without other neurological impairments or changes in strength of other muscles, subacromial impingement could then develop overtime. However, we observed improvement in ROM of the GH joint in our cases after botulinum injection to the rhomboids muscles. This improvement is based on a different pathophysiological mechanism. As mentioned in the introduction, there is sustained spontaneous motor unit firing in spastic muscles in stroke patients.5–7 This suggests that involuntary activation of spastic rhomboids muscle maintains the scapula in elevated and medially rotated position (Figure 2). This is consistent with visual inspection of the scapula in our cases. The scapula in such a position certainly limits ROM of the GH joint, particularly in flexion and abduction. Botulinum toxin blocks neuromuscular junction presynaptically,4 thus reducing involuntary activation in spastic rhomboids muscles, that is, decreasing constant medial and upper rotation of the scapula. As a result, the scapula is more mobile during the GH movement. The clinical outcome of increased active ROM of the GH joint after injection, particularly in flexion and abduction, is a reflection of this process. In the second case, the low trapezius muscle was also injected. A similar good result of this case supports the idea that low trapezius functions similar to rhomboid makes the scapula rotate medially. We did not measure scapular position before and after injection for these 2 cases. Future studies with measurement of scapular position are needed to better understand the change of scapular motion after injection.

CONCLUSION

The findings in these 2 cases suggest that spastic scapular dyskinesia can lead to impaired shoulder active and passive ROM after stroke, though rare. Botulinum toxin injection to spastic muscles is promising for management of spastic scapular dyskinesia. However, other etiologies that cause limited shoulder ROM need to be ruled out first. This is a preliminary study. Further studies are required to optimize the dosage of botulinum toxin. Furthermore, therapy for scapular mobilization and ROM is recommended after injection to maximize the outcome of injection.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: EMG = electromyographic, GH = glenohumeral, MCA = middle cerebral artery, OT = occupational therapy, PT = physical therapy, ROM = range of motion.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Li S, Francisco G. New insights into the pathophysiology of post-stroke spasticity. Front Hum Neurosci 2015; 9:192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brashear A, Gordon MF, Elovic E, et al. Intramuscular injection of botulinum toxin for the treatment of wrist and finger spasticity after a stroke. N Engl J Med 2002; 347:395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaw LC, Price CI, van Wijck FM, et al. Botulinum Toxin for the Upper Limb after Stroke (BoTULS) Trial: effect on impairment, activity limitation, and pain. Stroke 2011; 42:1371–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jahn R. Neuroscience. A neuronal receptor for botulinum toxin. Science 2006; 312:540–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mottram CJ, Suresh NL, Heckman CJ, et al. Origins of abnormal excitability in biceps brachii motoneurons of spastic-paretic stroke survivors. J Neurophysiol 2009; 102:2026–2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mottram CJ, Wallace CL, Chikando CN, et al. Origins of spontaneous firing of motor units in the spastic-paretic biceps brachii muscle of stroke survivors. J Neurophysiol 2010; 104:3168–3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang SH, Francisco GE, Zhou P, et al. Spasticity, weakness, force variability, and sustained spontaneous motor unit discharges of resting spastic-paretic biceps brachii muscles in chronic stroke. Muscle Nerve 2013; 48:85–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bensmail D, Robertson J, Fermanian C, et al. Botulinum toxin to treat upper-limb spasticity in hemiparetic patients: grasp strategies and kinematics of reach-to-grasp movements. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2010; 24:141–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang SH, Francisco GE, Li S. Botulinum toxin (BT) injection improves voluntary motor control in selected patients with post-stroke spasticity. Neural Regen Res 2012; 7:1436–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abbott Z, Richardson JK. Subacromial impingement syndrome as a consequence of botulinum therapy to the upper trapezii: a case report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007; 88:947–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robert-Lachaine X, Marion P, Godbout V, et al. Elucidating the scapula-humeral rhythm calculation: 3D joint contribution method. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin 2015; 18:249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pellegrini A, Tonino P, Paladini P, et al. Motion analysis assessment of alterations in the scapulo-humeral rhythm after throwing in baseball pitchers. Musculoskelet Surg 2013; 97 Suppl 1:9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]