Abstract

The aim of this study is to assess the influence of surgeon specialization on outcomes following appendicectomy in children.

General surgeons and pediatric surgeons manage appendicitis in children; however, the influence of subspecialization on outcomes remains unclear.

Two authors searched Medline and Embase to identify relevant studies. Eligible studies were comparative and provided data on children who had appendicectomy while under the care of general or pediatric surgical teams. Two authors initially screened titles and abstracts and then full text manuscripts were evaluated. Data were extracted by 2 authors using an electronic spreadsheet. Pooled risk ratios and pooled mean differences were used in analyses.

We identified 9 relevant studies involving 50,963 children who were managed by general surgery teams and 15,032 children who were managed by pediatric surgery teams. A normal appendix was removed in 4660/48,105 children treated by general surgery units and in 889/14,760 children treated by pediatric units (pooled risk ratio 1.79; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.26–2.54; P = 0.001). Children managed in general units had shorter mean hospital stays compared with children managed in pediatric units (pooled mean difference −0.70 days; 95%CI −1.09 to −0.30; P = 0.0005). There were no significant differences regarding wound infections, intra-abdominal abscesses, readmissions, or mortality.

We found that children who were managed by specialized pediatric surgery teams had lower rates of negative appendicectomy although mean length of stay was longer. Our article is based upon a group of heterogeneous and mostly retrospective studies and therefore there is little external validity. Further studies are needed.

INTRODUCTION

Appendicitis is the most common pediatric surgical emergency.1 There are in excess of 40,000 cases in England annually1 and its incidence is about 9.4 cases per 10,000 patient years.2 In 2010, the Global Burden of Disease Study estimated that appendicitis causes 19 years of life lost per 100,000 population and 21 disability adjusted life years per 100,000 population globally;3 therefore, it is important that we strive to improve the management of appendicitis.

An expanding body of evidence suggests that surgeon subspecialization affects outcomes; studies found that colorectal surgery subspecialization4 and orthopedic surgery subspecialization5 lead to improved results and that outcomes from a variety of cancers are improved with subspecialization.6 Higher volume surgeons have also been shown to generate improved outcomes.7 At present, appendicitis in pediatric patients is managed by both general surgeons and specialized pediatric surgeons;8 however, the influence of surgeon subspecialization on outcomes is unclear. We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the influence of surgeon subspecialty on outcomes following appendicectomy in children. Our hypothesis was that surgeon specialization influences outcomes in appendicitis in children.

METHODS

This systematic article was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. There was no requirement for ethical approval.

Eligible studies were comparative and provided data on children who had appendicectomy while under the care of general or pediatric surgical teams. Randomized and observational studies were eligible. Eligible studies had to report on at least 1 of the following outcomes: normal appendicectomy rate, wound infections, intra-abdominal collections, readmissions, mortality, and length of stay. We excluded studies that reported selectively on laparoscopic or open procedures. We also excluded review articles, case reports, and case series and we limited eligibility to English language studies.

In order to identify studies and determine eligibility, 2 authors (DD and MM) independently searched Medline and EMBASE up to June 24, 2015 using the following search strategy “([paediatric surgery OR pediatric surgery OR pediatric surgeon OR paediatric surgeon] AND (appendectomy OR appendicectomy)].” The search terms were inputted as free text. Titles and abstracts were examined initially and then full manuscripts were obtained to finalize eligibility. The reference lists of eligible studies were examined to identify further studies. In cases where there was disagreement regarding eligibility, a third reviewer (DH) was consulted. In addition, conference abstracts from a variety of pediatric surgery meetings were searched by 1 author (EM). These comprised the Surgical Section of the American Academy of Pediatrics (2004–2014), the British Association of Paediatric Surgeons (2004–2014), the American Pediatric Surgical Association (2004–2014), the Canadian Association of Paediatric Surgeons (2004–2014), the Pacific Association of Pediatric Surgeons (2004–2014), the Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland (2004–2014), and the American College of Surgery (2004–2014).

Two authors (DD and DH) independently extracted data from eligible studies using an electronic spreadsheet. Extracted data comprised details on the following variables: lead author, publication date, study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, outcomes reported, whether there was a specified primary endpoint, main results, numbers and characteristics of patients, surgical approach, rate of negative appendiceal histology, wound infections, intra-abdominal collections, readmissions, mortality, and length of stay. The outcomes for the meta-analysis were rates of negative appendiceal histology, wound infections, intra-abdominal collections, readmissions, mortality, and length of stay. Definitions and timeframes for these outcomes were those specified in individual manuscripts.

Study quality was assessed using the Downs and Black tool.9 This involves 27 questions that evaluate reporting quality as well as internal and external validity. The checklist allows scores from 0 to 32 which includes a score of 0 to 5 for sample size estimation. We modified the sample size estimation section by awarding 1 point for providing justification for sample size and no point in the absence of justification. Therefore, our quality checklist could award scores varying from 0 to 27 with larger scores denoting higher quality.

Statistical analyses were completed using RevMan version 5.310 (Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). Pooled risk ratios and pooled mean differences were used to evaluate the effect of treatment by general surgery units or pediatric surgery units on dichotomous and continuous outcomes, respectively. We used Mantel Haenszel random effects models. The potential for publication bias was evaluated by visually inspecting funnel plots. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic. Higher I2 values indicate increased heterogeneity. Results were given with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and P values where appropriate and we used the 5% level for significance.

RESULTS

We identified 1035 Medline sources and 1868 Embase sources. Figure 1 summarizes the results of the search. A total of 1841 citations were excluded based on titles and abstracts. A total of 27 full text manuscripts were examined and 9 studies were finally eligible for inclusion. No additional studies were identified from the gray literature search or from searching included article reference lists.

FIGURE 1.

Results of the search.

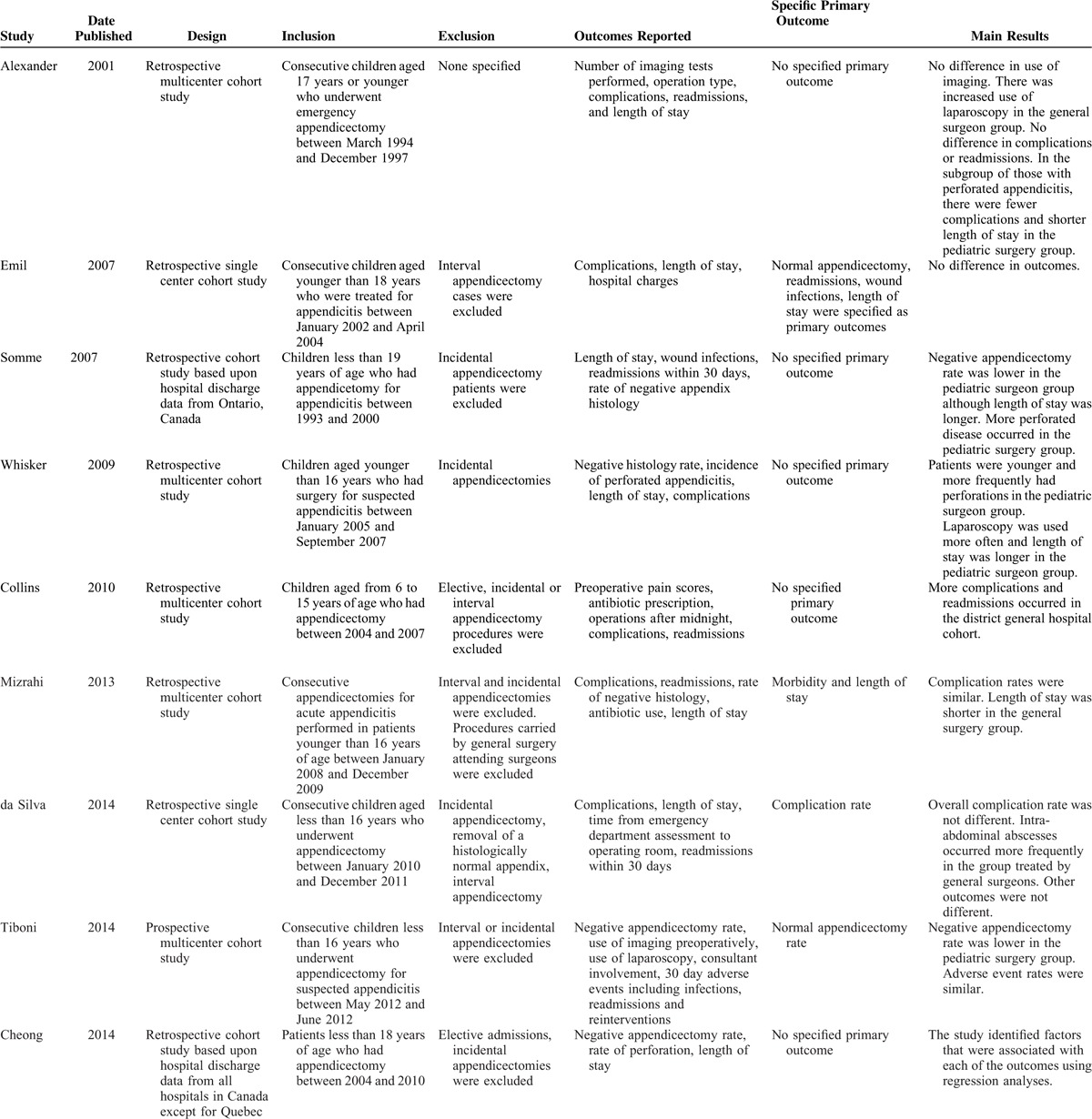

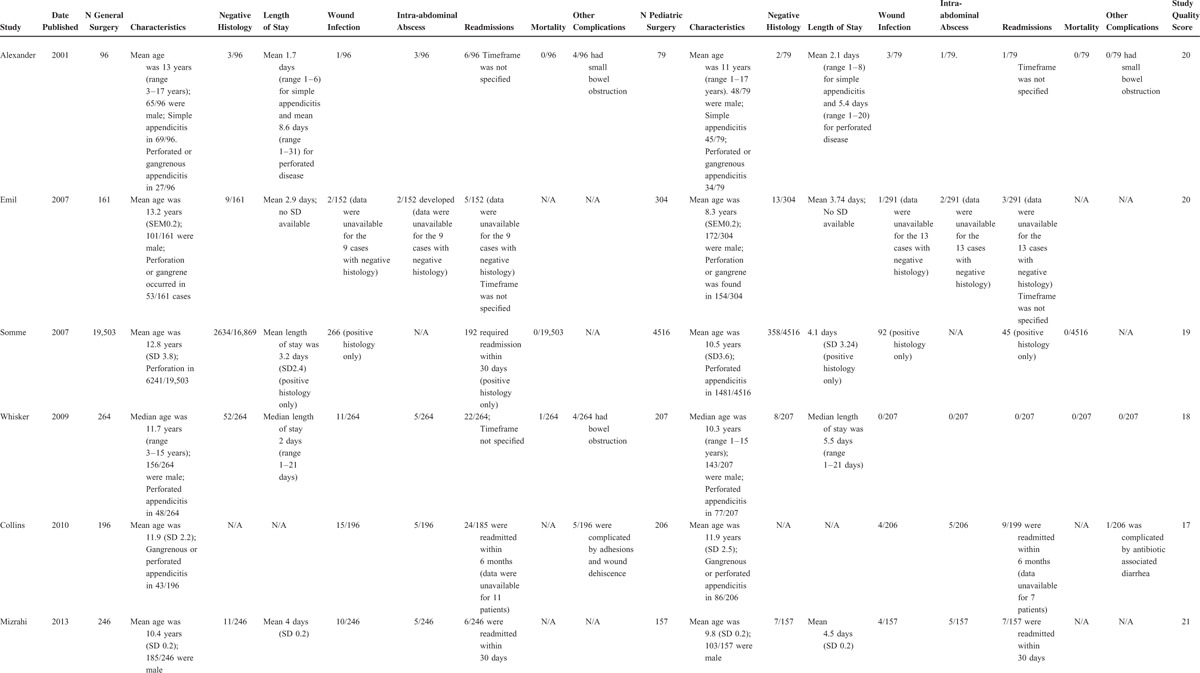

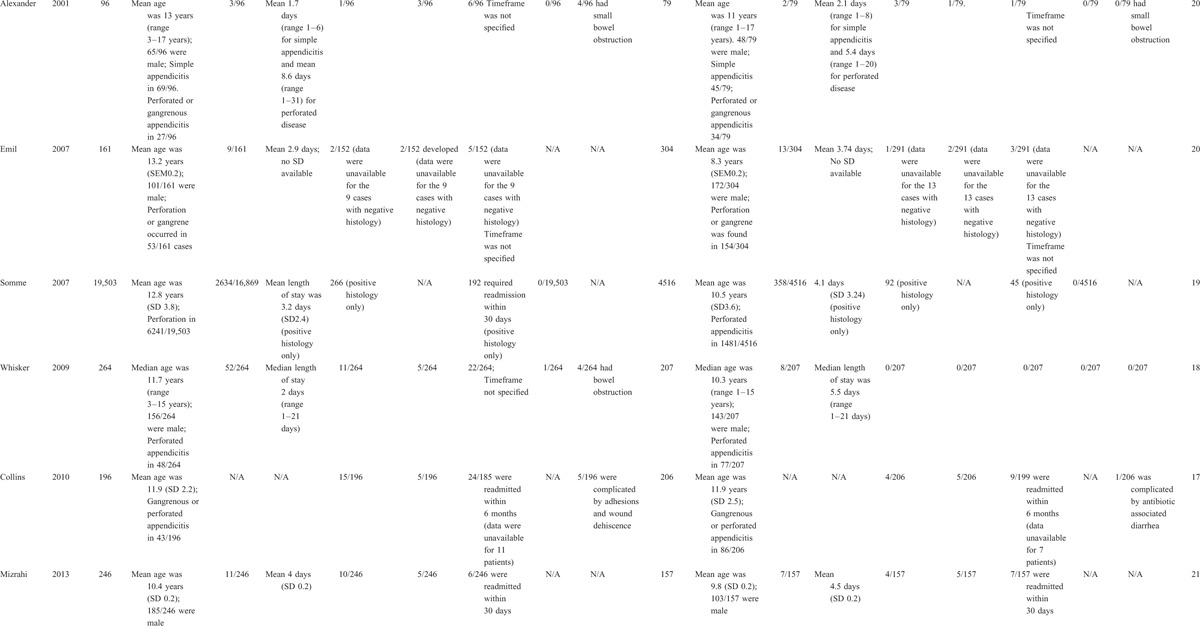

Characteristics of the 9 included studies8,11–18 are shown in Table 1 and results from the studies are provided in Table 2 . In total the studies comprised 50,963 children who were managed by general surgery units and 15,032 children who were managed by pediatric surgery units. Nine of the studies11–18 were retrospective cohort studies and 18 was a prospective cohort study. Two studies (63,282 children) were retrospective analyses of registry-based hospital discharge data.13,18 The other 7 studies (2713 children) concerned specified institutions and were either single-center12,17 or multicenter.8,11,14–16 Recruitment dates for included studies spanned the period from 1993 to 2012. The age ranges for the eligibility of patients within studies also varied – the maximum age of any included patient was 18 years. No study reported explicitly on criteria that determined whether patients were managed by general surgery teams or pediatric surgery teams – however we think that allocation is likely to have reflected the nature of the on-call team and available resources at any particular time. Most of the studies reported on the proportions of patients who underwent laparoscopic or open appendicectomy procedures8,11,12,14,16,17 although these data were not reported in some studies.13,15,18,19 Few studies reported conversion rates from laparoscopic to open surgery.8,16 Only 2 studies8,17 specified a single primary endpoint: 1 favored the pediatric surgery group8 and there was no primary outcome difference in the other.17 The results of the quality assessment are available in a supplementary table and are also summarized in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies

TABLE 2.

Results from Included Studies

TABLE 2 (Continued).

Results from Included Studies

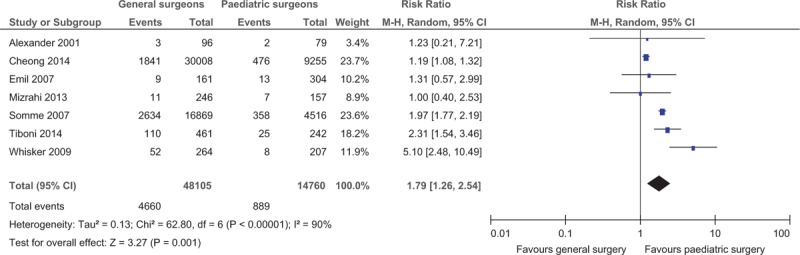

Seven studies8,11–14,16,18 (62,865 children) reported on numbers of histologically negative appendicectomies. A normal appendix was removed in 4660/48,105 children treated by general surgery units and in 889/14,760 children treated by pediatric units (pooled risk ratio 1.79; 95%CI 1.26–2.54; P = 0.001) (Figure 2). There was evidence for considerable heterogeneity with an I2 value of 90%. The funnel plot did not suggest publication bias.

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot for negative appendicectomy rate.

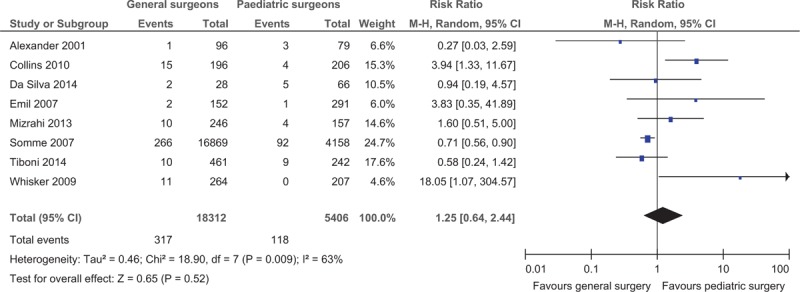

Eight studies8,11–17 (23,718 children) reported on wound infections. This complication occurred in 317/18,312 children treated by general surgery units versus 118/5406 children who were treated in pediatric surgery units (pooled risk ratio 1.25; 95%CI 0.64–2.44; P = 0.52) (Figure 3). There was substantial heterogeneity with an I2 statistic of 63%. The funnel plot did not suggest publication bias.

FIGURE 3.

Forest plot for wound infections.

Seven studies8,11,12,14–17 (2691 children) reported on intra-abdominal collections. This complication occurred in 34/1443 children who were treated in general surgery units versus 32/1248 children who were treated in pediatric units (pooled risk ratio 1.24; 95%CI 0.47–3.25; P = 0.66). There was evidence for substantial heterogeneity with an I2 statistic of 61%. The funnel plot was asymmetrical indicating possible publication bias.

Eight studies8,11–17 (23,700 children) reported on readmissions. This occurred in 285/18,301 children treated in general surgery units versus 90/5399 children managed in pediatric surgery units (pooled risk ratio 1.62; 95%CI 0.85–3.06; P = 0.14). There was evidence for substantial heterogeneity with an I2 statistic of 73%. The funnel plot did not suggest bias.

Three studies11,13,14 (24,665 children) reported mortality. One of 19,863 children managed by general surgery units died versus 0/4802 managed by pediatric surgery units (pooled risk ratio 2.35; 95%CI 0.10–57.51; P = 0.6). It was not possible to general an I2 statistic based upon these data. The funnel plot did not suggest bias.

Two studies13,16 (21,430 children) reported on length of hospital stay. Children managed in general units (17,115 children) had shorter mean hospital stays compared with children managed in pediatric units (4315 children) (pooled mean difference −0.70 days; 95%CI −1.09 to −0.30; P = 0.0005). There was evidence for considerable heterogeneity with an I2 statistic of 98%. The funnel plot did not suggest bias.

DISCUSSION

In our article, we examined the influence of surgical specialty on outcomes following pediatric appendicectomy procedures. We included 9 studies comprising 65,995 children and focused on patient important outcomes. We found that children who were managed by general surgeons were more likely to have removal of a histologically normal appendix (pooled risk ratio 1.79; 95%CI 1.26–2.54; P = 0.001) and mean length of stay was significantly longer in children treated by pediatric surgeons (pooled mean difference 0.70 days; 95%CI 0.30 to 1.09; P = 0.0005) compared with those treated by general surgeons. There were no significant differences between the groups regarding wound infections, intra-abdominal collections, and readmission rates. We think that our findings are noteworthy because appendicectomy is the most common pediatric surgical emergency. Despite this, our findings must be interpreted with caution as our article is based entirely upon observational data.

Several noncausal factors may account for the observed difference in the negative appendicectomy rate. One possibility is that specialized pediatric units may have better access to high quality imaging. Four studies reported on the use of preoperative imaging8,11,16,17 – 1 study found no difference in use of imaging,11 2 studies found that children who were managed by specialized pediatric surgical teams were more likely to have undergone ultrasound scanning.8,17 The final study found similar overall use of imaging (computed tomography scanning and ultrasonography) across the groups but more use of computed tomography in the general surgery group.16 Another possible explanation relates to the tendency for children with more severe disease to have been managed by pediatric surgical teams – in many of the included study rates of perforation and gangrene were higher in the pediatric surgery group (Table 2 ). Another possibility is that management in pediatric units may reflect enhanced processes of care. It is important to highlight that both groups in our article had acceptably low-negative appendicectomy rates (9.7% in the general surgery group versus 6% in the pediatric surgery group) but nonetheless any true improvement in this outcome is likely to be clinically meaningful. Regarding the difference in length of stay, we think that the difference we observed probably reflects the tendency for younger children and children with more severe disease (Table 2 ) to have been managed by pediatric surgical teams. Another consideration is that the shorter length of stay in the general surgery group may be a reflection of the higher negative appendicectomy rate in this group. However with the limited available summary data, it is not possible to explore these theories at present. It is noteworthy that we found no difference in wound infections, intra-abdominal infections, readmissions, and mortality even though our sample sizes for these outcomes were considerable.

The principle strength of our review is our exhaustive search strategy which included a detailed gray literature search. It yielded a large number of eligible studies and patients. We focused on patient important outcomes and we extracted and presented data on a wide range of important baseline factors. Regarding limitations, the main issue is the retrospective nature of most of the included studies. Only one involved prospective data collection.8 Furthermore, no randomized data were available and therefore our review is prone to biases and confounding. We aimed to make this limitation as transparent as possible by reporting clearly on study characteristics and by including quality assessment scores (Table 2 ). We also wish to highlight that a large proportion of our data came from discharge registries13,18 which are known to be prone to inaccuracies. Overall, these limitations limit the external validity of this article. Additionally, it is notable that our study evaluated surgeon specialization rather than institutional specialization.

We wish to encourage further research on outcomes in pediatric appendicitis. Randomized trials are unfeasible given the likely logistic difficulties and the large sample sizes that would be required for a trial to demonstrate superiority in relation to any outcome; therefore, we think that prospective multicenter appendicectomy registries represent the most feasible study design. Such databases will need to consider a range of baseline, predischarge and postdischarge factors in order to generate externally valid conclusions. We wish to emphasize the need to consider the effect of clustering in future studies – this is an often ignored source of bias in such studies (none of the studies in this article provided data on outcomes from individual surgeons).

CONCLUSIONS

We found that children who were managed by specialized pediatric surgery teams had lower rates of negative appendicectomy although mean length of stay was longer in this group. However, our article is based upon a group of heterogeneous and mostly retrospective studies, and therefore there is little external validity. We wish to encourage future research through the use of large-scale prospective multicenter registries.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval, CT = computed tomography, IQR = interquartile range, N/A = not available, PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses, SD = standard deviation, SEM = standard error of the mean.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alloo J, Gerstle T, Shilyansky J, et al. Appendicitis in children less than 3 years of age: a 28-year review. Pediatr Surg Int 2004; 19:777–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aarabi S, Sidhwa F, Riehle KJ, et al. Pediatric appendicitis in New England: epidemiology and outcomes. J Pediatr Surg 2011; 46:1106–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart B, Khanduri P, McCord C, et al. Global disease burden of conditions requiring emergency surgery. Br J Surg 2014; 101:e9–e22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Archampong D, Borowski D, Wille-Jorgensen P, et al. Workload and surgeon's specialty for outcome after colorectal cancer surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 3:CD005391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hagen TP, Vaughan-Sarrazin MS, Cram P. Relation between hospital orthopaedic specialisation and outcomes in patients aged 65 and older: retrospective analysis of US Medicare data. BMJ 2010; 340:c165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hillner BE, Smith TJ, Desch CE. Hospital and physician volume or specialization and outcomes in cancer treatment: importance in quality of cancer care. J Clin Oncol 2000; 18:2327–2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halm EA, Lee C, Chassin MR. Is volume related to outcome in health care? A systematic review and methodologic critique of the literature. Ann Intern Med 2002; 137:511–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tiboni S, Bhangu A, Hall NJ. Outcome of appendicectomy in children performed in paediatric surgery units compared with general surgery units. Br J Surg 2014; 101:707–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health 1998; 52:377–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexander F, Magnuson D, DiFiore J, et al. Specialty versus generalist care of children with appendicitis: an outcome comparison. J Pediatr Surg 2001; 36:1510–1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emil SG, Taylor MB. Appendicitis in children treated by pediatric versus general surgeons. J Am Coll Surg 2007; 204:34–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Somme S, To T, Langer JC. Effect of subspecialty training on outcome after pediatric appendectomy. J Pediatr Surg 2007; 42:221–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whisker L, Luke D, Hendrickse C, et al. Appendicitis in children: a comparative study between a specialist paediatric centre and a district general hospital. J Pediatr Surg 2009; 44:362–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collins HL, Almond SL, Thompson B, et al. Comparison of childhood appendicitis management in the regional paediatric surgery unit and the district general hospital. J Pediatr Surg 2010; 45:300–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mizrahi I, Mazeh H, Levy Y, et al. Comparison of pediatric appendectomy outcomes between pediatric surgeons and general surgery residents. J Surg Res 2013; 180:185–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.da Silva PS, de Aguiar VE, Waisberg J. Pediatric surgeon vs general surgeon: does subspecialty training affect the outcome of appendicitis? Pediatr Int 2014; 56:248–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheong LH, Emil S. Determinants of appendicitis outcomes in Canadian children. J Pediatr Surg 2014; 49:777–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kokoska ER, Minkes RK, Silen ML, et al. Effect of pediatric surgical practice on the treatment of children with appendicitis. Pediatrics 2001; 107:1298–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]