SUMMARY

In this study, Leishmaniaspecies were identified by Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). The epidemiology of patients suspected of having American Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in the municipality of Assis Brasil, Acre State, located in the Brazil/Peru/Bolivia triborder was also investigated. By PCR, the DNA of Leishmaniawas detected in 100% of the cases (37 samples) and a PCR-Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (RFLP) of the hsp 70gene identified the species in 32 samples: Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis (65.6%) , L. (V.) shawi (28.1%) , L. (V.) guyanensis (3.1%) and mixed infection L. (V.) guyanensis and L. (Leishmania) amazonensis (3.1%)This is the first report of L. (V.) shawiand L. (L.) amazonensis in Acre. The two predominant species were found in patients living in urban and rural areas. Most cases were found in males living in rural areas for at least three years and involved in rural work. This suggests, in most cases, a possible transmission of the disease from a rural/forest source, although some patients had not engaged in activities associated with permanence in forestall areas, which indicate a possible sandflies adaptation to the periurban setting.

KEY WORDS: Leishmania, Acre State, PCR

RESUMO

O presente estudo caracterizou as espécies de Leishmaniapela Reação em Cadeia da Polimerase (PCR). Também descreveu os aspectos epidemiológicos de pacientes com suspeita de leishmaniose tegumentar americana do município de Assis Brasil, Estado do Acre, Brasil, localizado na tríplice fronteira Brasil/Peru/Bolívia. A PCR detectou DNA de Leishmaniaem 100% dos casos (37 amostras) e a PCR- Restriction Fragment Length Polymorfism(RFLP) do gene hsp 70identificou as espécies em 32 amostras: Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis (65,6%) , L. (V.) shawi (28,1%) , L. (V.) guyanensis (3,1%) e infecção mista L. (V.) guyanensis e L. (Leishmania) amazonensis(3,1%)Esse é o primeiro registro de L. (V.) shawie L. (L.) amazonensis no Acre. As duas espécies predominantes foram encontradas em indivíduos residentes em áreas rurais e urbanas. O maior número de casos foi notificado entre indivíduos de áreas rurais, sexo masculino, de ocupação rural e tempo de residência maior que três anos. Esses dados sugerem possível transmissão da doença em ambiente rural/florestal na maioria dos casos, no entanto alguns pacientes não tinham envolvimento com atividades relacionadas com a permanência na floresta, indicando possível adaptação de flebotomíneos no ambiente periurbano.

INTRODUCTION

American Cutaneous Leishmaniasis (ACL) is an infectious-parasitic disease caused by different species of protozoa of the Leishmaniagenus that is transmitted to humans by phlebotomine flies.19 Although there was a decreased incidence of ACL in Brazil, due to Brazilian socioeconomic improvement and increased environmental monitoring over the last 15 years, providing a decrease of people exposed to the vectors26, the disease still persists in the country with a high number of cases. Between 2010 and 2012, 68,855 occurrences of ACL were recorded in Brazil. The disease occurs in several endemic areas, 40% of which are found in the North, the area of higher endemicity. Acre was the unit of the federation with the highest incidence of ACL, with 141.64 cases per 100,000 inhabitants in 20104.

In spite of the high incidence of ACL in Acre, the published clinical and demographic studies about this disease are based on the data provided by the Ministry of Health16 , 22 , 23. The only exception is an epidemiological study in Rio Branco, in which Leishmaniaspecies were characterized using molecular biology techniques27.

The identification of Leishmania species from endemic areas is an important step in our understanding of the epidemiology of ACL that could improve its diagnostic and prognostic, and also contribute to the implementation of control and epidemiological surveillance measures20 , 27. The Polymerase Chain Reaction - Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) of samples obtained from leishmaniasis-like lesions - can distinguish the different pathogenic species and this method is more sensitive than the conventional method, which is a parasitological examination performed with an optical microscope7 , 20.

In the majority of Acre municipalities, the reports of ACL are based on non-specific tests, such as the Montenegro's intradermal-reaction, direct microscopic examination and clinical-epidemiological findings16 , 22 , 23. In Acre, the epidemiological profile study of ACL and its control must be considered in a special context, because this is a region that borders with two endemic countries for ACL: Peru/Madre de Dios, with 380 cases/100,000 inhabitants from 2000 to 2012 and Bolivia/Pando, with 659 cases/100,000 inhabitants in 20123 , 18.

Assis Brasil/Brazil is located in the microregion of Brasileia, which, together with the microregion of Rio Branco, is an endemic area of epidemiological relevance for ACL in the Acre State 22 , 23. Between 2007 and 2010, a total of 227 cases were reported in the municipality, which corresponds to a mean detection coefficient of 1,027 ACL cases per 100,000 inhabitants.4 This was the first study performed in the municipality that used molecular methods to characterize the Leishmania from ACL patients

The diagnostic of ACL was performed on 37 patients that spontaneously attended the Basic Urban Health Unit of Assis Brasil between August 2012 and December 2013 with cutaneous lesions raising the suspicion of ACL. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee in Human Research of the Instituto de Ciências Biomédicas - USP (nº 77885/2012). Each patient underwent a clinical examination. A biopsy was collected and sent to the Genetics Laboratory of Fiocruz Rondônia for the PCR assay.

During the medical appointment, the following clinicalepidemiological data were collected: sex, age, address (rural or urban), type of lesion (cutaneous, cutaneous-mucosal, and diffuse cutaneous), time since the lesion was detected, if it was a recurring lesion, what type of treatment had been used (which drug) and whether there had been any progress towards the clinical cure of the lesion. Additional information on the patients' occupations was also gathered in the following categories: rural (such as farmers, herdsmen, professors and students from rural areas), non-rural (military personnel, journalists and drivers) and others (housewives, retired workers and children).

The DNA was extracted from the biopsies according to the recommendations of the manufacturer (PureLink Genomic DNA Mini Kit(tm); Invitrogen(r) Carlsbad, CA, USA). To identify the Leishmania genus, PCR was performed as described by OLIVEIRA et al.16. This PCR targeting a conserved region of the Leishmania kDNA minicircle (PCR mkDNA) was performed with primers 5'-GGG(GT) AGGGGCGTTCT(G/C)CGAA-3' and 5'-(G/C)(G/C)(G/C)(A/T) CTAT(A/T)TTACAC CAACCCC3'. The final volume of the PCR reactions was 25 µL (18.7 µL of Milli-Q water; 2.5 µL of Buffer Green; 0.75 µL of MgCl2 (2 mM final); 0.38 µL of each mkDNA primer (1 µmol final); 0.50 µL of dNTPs (0.2 mM final); 0.25 µL of Taq Polymerase (1.25 U); 2 µL of DNA). The amplification conditions were: 94 ºC denaturation for five minutes, 40 cycles at 94 ºC for 30 seconds, 55 ºC for 30 seconds and 72 ºC for 45 seconds, and a final extension at 72 ºC for 10 minutes.

In order to identify the Leishmania species from the human biopsies, a fragment of the hsp70 gene was amplified (PCR hsp70) with primers hsp 70cF 5'-GGACGAGATCGAGCGCATG GT-3' and hsp 70cR 5'-TCCTTCGACGCCTCCTGGTTG-3' (adapted from GRAÇA et al.)8. The PCR mix composition was: 36.25 µL of Milli-Q water, 5.0 µL of Buffer Green; 1.5 µL of MgCl2 (2 mM); 1.0 µL of each primer hsp70 (1 µmol final); 2.0 µL of dNTPs (0.2 mM final); 0.5 µL of Taq Polymerase (1.25 U); 5.0 µL of DNA, for a final volume of 52.25 µL. The amplification conditions were: 94 ºC denaturation for four minutes, 33 cycles at 94 ºC for 15 seconds, 58 ºC for 30 seconds and 72 ºC for 30 seconds, and a final extension at 72 ºC for 10 minutes.

The mkDNA (120 pb) hsp70 (234 pb) amplicons were analyzed on a 2% agarose gel stained with GelRed and examined under UV light.

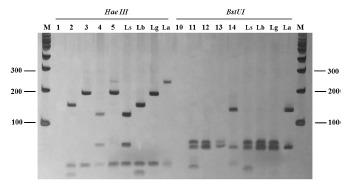

For the digestion of the hsp70 amplicons, the restriction enzymes HaeIII (Invitrogen(r), USA) and BstUI (Bio Labs(r), New England) were used in independent reactions according to the recommendations of the manufacturer. The resulting products of the restriction digestion were analyzed on a silver-stained 12% polyacrylamide gel (Fig. 1). As a positive control for the PCR and RFLP reactions, DNAs of reference strains of the Leishmania collection from the Instituto Oswaldo Cruz (CLIOC) were used, namely: L. (V.) braziliensis (IOCL 566), L.(V.) guyanensis (IOCL 565), L. (V.) lainsoni(IOCL 1023), L. (V.) naiffi (IOCL 1365), L. (V.) shawi (IOCL 1545) and L. (L.) amazonensis (IOCL 575). As negative controls, a PCR reaction mix without DNA was used.

Fig.1. Amplicons of hsp70 (234 pb) after digestion with Hae III and BstUI from samples of patients suspected of having ACL. Silver-stained 12% polyacrylamide gel. Lanes 1 and 10: negative control; Lanes 2 and 11: sample from patient 01; Lanes 3 and 12: sample from patient 02; Lanes 4 and 13: sample from patient 03; Lanes 5 and 14: sample from patient 04 with mixed infection; Ls: L. (V.) shawi; Lb: L. (V.) braziliensis; Lg: L. (V.) guyanensis; La: L. (L.) amazonensis. M: 100 pb molecular weight marker (Invitrogen(r)).

Measures of central tendency (mean, Md = median, standard deviation, and Q = quartiles) were used for the descriptive analysis, and to calculate the proportions and the confidence interval (IC 95%) for each variable.

PCR for the genus Leishmania was positive in the 37 samples. The hsp70 PCR identified four species in 32 (86.4%) samples: Leishmania (V.) braziliensis (21/32; 65.6%), L. (V.) guyanensis (1/32; 3.1%), L. (V.) shawi (9/32; 28.1%) and a mixed infection (1/32; 3.1%) by L. (V.) guyanensis and L. (L.) amazonensis; notably, this is the first report of L. (V.) shawi and L. (L.) amazonensis in Acre. In the microregion of Rio Branco, besides Leishmania (V.) braziliensis and L. (V.) guyanensis, L. (V.) lainsoni and L. (V.) naiffi have also been identified27. Except for L. (V.) shawi, the species that have been described in Acre were also found in other regions of Occidental Amazonia: in Rondônia State, species Leishmania (V.) braziliensis, L. (V.) lainsoni, and L. (V.) guyanensis 21 were reported; and in Amazonas State, L. (L.) amazonensis, L. (V.) braziliensis, L. (V.) guyanensis and L. (V.) naiffi have been detected1 , 9 , 25, L. (V.) guyanensis being the most frequent species6 , 10.

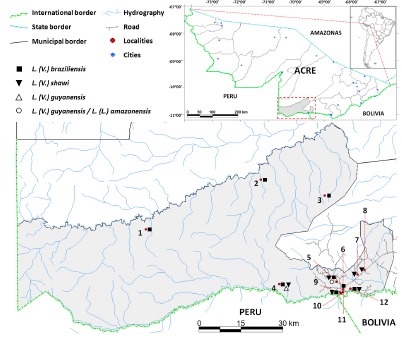

L. (V.) braziliensis was the most common species in this study, similar to observations in the microregion of Rio Branco and other areas in Bolivia and in the Peruvian State of Madre de Dios 8 , 27 , 28. It is possible that the high number of L. (V.) braziliensis in Assis Brasil/Brazil and its broad geographical spreading in the municipality (Fig. 2) was related to the several phlebotominae species adapted to both the rural/forest and peridomicile environments. Lu. wellcomei, Lu. migonei, Lu. carrerai, Lu. davisi and Lu. whitmani were the potential L. braziliensisvectors19, the latter two notable for their relative abundance in Acre State 2 , 24.

Fig. 2. Geographic distribution of the Leishmania spp. from patients attended in Assis Brasil (AC) suspected of having ACL. Each symbol represents one or more specimens collected in a given region. 1: Mamoadate Indigenous reserve; 2: Icuriã Extractive rubber reserve; 3: Guanabara Extractive rubber reserve; 4: São Francisco Extractive rubber reserve; 5: Paraguaçu Extractive rubber reserve; 6: Federal highway BR 317 km 2; 7: Federal highway BR 317 km 10; 8: Federal highway BR 317 km 13; 9: Centro Neighborhood; 10: Cascata Neighborhood; 11: Bela Vista Neighborhood; 12: Santa QuitériaExtractive rubber reserve.

The identification of L. (V.) braziliensis as the predominant species is a relevant epidemiological factor, given that this species is the mainly responsible for the evolution of the mucosal form of ACL in Latin America11 , 27. In Assis Brasil/Brazil, from 2003 to 2010, there were 53.5% confirmed cases of the cutaneous form, 17% confirmed cases of the mucosal form, and 29.5% for which there was no information of the clinical form16. Besides its association with the mucosal form of the disease, L. (V.) braziliensis is also considered a therapeutic challenge14. The study found three recurring cases infected by that species, and from the six clinical cases that underwent two cycles of treatment with meglumine antimoniate (glucantime) for lesions heal, five were infected with L. (V.) braziliensis.

L. (V.) shawi, the second most common species in this study, was recently identified in cutaneous lesions from patients of Madre de Dios/ Peru13, sporadically in cases of the Brazilian Amazonas region, namely in Pará, where it was isolated in cutaneous lesions12, and recently was also reported in Pernambuco5, Northeastern Brazil. The presence of this species could be linked to the presence of the phlebotomine Lu. whitmani 19.

The identification of L. (V.) guyanensis and L. (L.) amazonensis has important epidemiological and clinical implications, because both species are associated with the development of metastases and a high failure rate of treatment with meglumine antimoniate9 , 11. L. (V.) guyanensis has been well characterized in the Amazon Basin, including Acre, Amapá, Roraima and Pará,with higher prevalence in the Amazonas State, where the parasite is associated with edentate animals and marsupials, and its main vector is Lu. umbratilis 9 , 19. The same vector has been reported in Acre/Brazil by AZEVEDO et al. 2. In Peru, L. (V.) guyanensis is one of the species more frequently found in cases of ACL, whereas L. (L.) amazonensis has a broad geographic distribution in Brazil, associated with different clinical forms, including the diffused form; its main reservoirs are rodents and marsupials, and the Lu. flaviscutellata and Lu. olmecaphlebotomines are the main vectors19. Although the finding of mixed infections by more than one species of Leishmania spp. obtained from clinical samples from a single lesion is rare, which was also observed in 14% of skin lesions characterized in Manaus/Brazil by COELHO et al. 6. For these authors, abundance and diversity of infected vectors in an endemic area may contribute to an increased reporting of cases with mixed infection.

The average duration of the cutaneous disease was 55.9 ± 40.7 days (Q1 = 30.0, Q3 = 90 days, Md = 33 days and n = 72.9%). The evolution of the disease in the studied group had a healing rate of 97.3% (36/37), the percentage of patients that abandoned treatment was 2.7% (1/37) and 16.2% (6/37) of the patients (five infected with L. (V.) braziliensis and one with L. (V.) shawi) were administered two cycles of treatment with meglumine antimoniate. Antimonial chemotherapy studies in Latin America have shown different healing rates (26% - 100%), including healing failure. Several factors can influence the outcome of treatment, such as evolution, number, size and location of the lesions, as well as the Leishmania species causing the infection14 , 15. The early diagnosis in the majority of the population studied, the sensitivity of the diagnostic tests (100% for the mKDNA PCR and 86.4% for the hsp70 PCR) to confirm disease and the access to the correct ACL treatment may explain the overall treatment success. These conditions may also reduce the risk of developing a mucosal lesion, which could appear years after the primo-infection.

Most of the ACL patients reported in this work have lived in a rural area (75.7%) for at least three years (70.3%), which suggests that these local cases are linked to activities in a forest environment (59.4%; 22/37). A higher percentage of male individuals was also observed (81.1%) and the age of the infected individuals varied from five to 46 years (Median = 23 years, Mean = 21.6 ± 10.6 years), with a higher percentage of young individuals in their productive years (15 - 40 years) (Table 1). Together, these data suggests that the transmission occurred outside of the residence during the working hours of the population studied. Such epidemiological profile has been observed, in Acre as in other regions of the Brazilian Amazon, which shows that ACL is an occupational disease, since most of the patients are men from rural areas engaged in activities associated with the permanence in the forest16 , 22 , 23 , 25. On the other hand, SILVA & MUNIZ22 reported a different epidemiological leishmaniasis profile in the microregion of Rio Branco, with increasing numbers in recent years of infected women and individuals living in urban areas, and with non-rural occupations. Although in that study the majority of positive cases are from rural areas, particularly Seringal Paraguaçu, Seringal Icuriã, Seringal São Francisco and Seringal Guanabara, which showed the highest indexes of ACL (13.5%, n = 5; 13.5%, n = 5; 11%, n = 4; 8%, n = 3, respectively), thus suggesting the classical rural/forest transmission, it should be noticed that several of those localities are in the periphery of the municipality urban center (Fig. 2). This is a matter of concern, because such proximity could favor the adaptation of infected vectors to intra and peridomicile in the municipality urban area.

Table 1. Epidemiological profile of patients examined in Assis Brasil (AC) with cutaneous lesions used in the diagnostic of Leishmania by PCR.

| Variables | Positive | % (CI 95%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 30 | 81.1 (66.1-91.3) |

| Female | 7 | 18.9 (8.7-33.8) | |

| Age | 0 - 11 | 7 | 18.9 (8.7-33.8) |

| 12 - 21 | 13 | 35.1 (21.1-51.4) | |

| 22 - 31 | 9 | 24.3 (12.5-39.9) | |

| 32 - 41 | 7 | 18.9 (8.7-33.8) | |

| ≥41 | 1 | 2.7 (0.1-12.6) | |

| Profession | Rural | 22 | 59.4 (43.2-74.3) |

| Non-Rural | 7 | 18.9 (8.7-33.8) | |

| Others | 8 | 22.6 (10.6-36.9) | |

| Area | Rural | 28 | 75.7 (60.0-87.4) |

| Urban | 9 | 24.3 (12.5-39.9) | |

| Localities | Seringal Paraguaçu | 5 | 13.5 |

| Seringal Icuriã | 5 | 13.5 | |

| Seringal São Francisco | 4 | 11 | |

| Seringal Guanabara | 3 | 8 | |

| Federal highway BR 317 | 3 | 8 | |

| Urban area | 9 | 24 | |

| Others | 8 | 22 | |

These data revealed a predominance of L. (V.) braziliensis in the ACL cases and that probably this disease is linked to rural life, particularly rural work. The presence of several Leishmania species supports a scenario of heterogeneous transmission, which calls for a broader epidemiological study that takes into consideration the vectors, reservoirs, virulence of the parasites and incidence of clinical forms.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) (Project number 08/11319-0) coordinated by Dr. Luís Marcelo Aranha Camargo.

Footnotes

FINANCIAL SUPPORT This work was supported by grants from Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) (Project number 08/11319-0) coordinated by Dr. Luís Marcelo Aranha Camargo.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arias JR, Freitas RA. Sobre os vetores de leishmaniose cutânea na Amazônia Central do Brasil. 2: Incidência de flagelados em flebótomos selváticos. Acta Amaz. 1978;8:38796–38796. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azevedo AC, Costa SM, Pinto MC, Souza JL, Cruz HC, Vidal J. Studies on the sandfly fauna (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) from transmission areas of American Cutaneous Leishmaniasis in state of Acre, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2008;103:760–767. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762008000800003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolívia. Ministério de Salud y Deporte . Sistema Nacional de Información en Salud y Vigilancia Epidemiológica. Bogotá: Ministerio de Salud y Deportes; 2012. http://www.sns.gob.bo/snis/default.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde . Sistema de Informação de Agravos de Notificação. O que é o SINAN. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2014. http://dtr2004.saude.gov.br/sinanweb [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brito ME, Andrade MS, Mendonça MG, Silva CJ, Almeida EL, Lima BS. Species diversity of Leishmania (Viannia) parasites circulating in an endemic area for cutaneous leishmaniasis located in the Atlantic rainforest region of northeastern Brazil. Trop Med Int Health. 2009;14:1278–1286. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Camara Coelho LI, Paes M, Guerra JA, Barbosa M, Coelho C, Lima B. Characterization of Leishmania spp. causing cutaneous leishmaniasis in Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil. Parasitol Res. 2011;108:671–677. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-2139-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graça GC, Volpini AC, Romero GA, Oliveira MP, Neto, Hueb M, Porrozzi R. Development and validation of PCR-based assays for diagnosis of American cutaneous leishmaniasis and identification of the parasite species. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2012;107:664–674. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762012000500014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia AL, Tellez T, Parrado R, Rojas E, Bermudez H, Dujardin JC. Epidemiological monitoring of American tegumentary leishmaniasis: molecular characterization of a peridomestic transmission cycle in the Amazonian lowlands of Bolivia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101:1208–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guerra JA, Prestes SR, Silveira H, Coelho LI, Gama P, Moura A. Mucosal leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis andLeishmania (Viannia) guyanensis in the Brazilian Amazon. PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5: doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guerra JA, Ribeiro JA, Coelho LI, Barbosa M, Paes MG. Epidemiologia da leishmaniose tegumentar na comunidade São João, Manaus, Amazonas, Brasil. Cad Saúde Pública. 2006;22:2319–2327. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2006001100006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costa JM, Saldanha AC, Nasciento D, Sampaio G, Carneiro F, Lisboa E. Modalidades clínicas, diagnóstico e abordagem terapêutica da leishmaniose tegumentar no Brasil. Gaz Med Bahia. 2009;79:70–83. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jennings YL, De Souza AA, Ishikawa EA, Shaw J, Lainson R, Silveira F. Phenotypic characterization of Leishmania spp. causing cutaneous leishmaniasis in the lower Amazon region, western Pará State, Brazil, reveals a putative hybrid parasite, Leishmania (Viannia) guyanensis andLeishmania (Viannia) shawi shawi. Parasite. 2014;21:39–39. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2014039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato H, Cáceres AG, Mimori T, Ishimaru Y, Sayed AS, Fujita M. Use of FTA cards for direct sampling of patients' lesions in the ecological study of cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:3661–3665. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00498-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Llanos-Cuentas A, Tulliano G, Araujo-Castillo R, Miranda-Verastegui C, SantamariaCastrellon G, Ramirez L. Clinical and parasite species risk factors for pentavalent antimonial treatment failure in cutaneous leishmaniasis in Peru. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:223–231. doi: 10.1086/524042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayrink W, Botelho AC, Magalhães PA, Batista SM, Lima AO, Genaro O. Immunotherapy, immunochemotherapy and chemotherapy for American cutaneous leishmaniasis treatment. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2006;39:14–21. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822006000100003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliart-Guzmán H, Martins AC, Mantovani SA, Braña AM, Delfino BM, Pereira TM. Características epidemiológicas da leishmaniose tegumentar americana na fronteira amazônica: estudo retrospectivo em Assis Brasil, Acre. Rev Patol Trop. 2013;42:187–200. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oliveira JG, Novais FO, de Oliveira CI, da Cruz AC, Junior, Campos LF, de Rocha AV. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is highy sensitive for diagnosis of mucosal leishmaniasis. Acta Trop. 2005;94:55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peru. Ministerio de Salud Análisis y tendencia de la leishmaniosis en el Perú: situación hasta agosto de 2012. Bol Epidemiol (Lima) 2012;21:600–603. http://www.dge.gob.pe/portal/docs/vigilancia/boletines/2012/37 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rangel EF, Lainson R. Proven and putative vectors of American cutaneous leishmaniasis in Brazil: aspects of their biology and vectorial competence. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104:937–954. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762009000700001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Satow MM, Yamashiro-Kanashiro EH, Rocha MC, Oyafuso LK, Soler RC, Cotrim PC. Applicability of kDNA-PCR for routine diagnosis of American Tegumentary Leishmaniasis in a tertiary reference hospital. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2013;55:393–399. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652013000600004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaw JJ, De Faria DL, Basano SA, Corbett CE, Rodrigues CJ, Ishikawa EA. The aetiological agents of American cutaneous leishmaniasis in the municipality of Monte Negro, Rondônia State, western Amazonia, Brazil. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2007;101:681–688. doi: 10.1179/136485907X229103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silva NS, Muniz VD. Epidemiologia da leishmaniose tegumentar Americana no estado do Acre, Amazônia brasileira. Cad Saude Publica. 2009;25:1325–1336. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2009000600015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silva NS, Viana AB, Cordeiro JA, Cavasini CE. Leishmaniose tegumentar no Estado do Acre, Brasil. Rev Saude Publica. 1999;33:554–559. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89101999000600006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silva-Nunes M, Cavasini CE, Silva NS, Galati EA. Epidemiologia da leishmaniose tegumentar e descrição das populações de flebotomíneos no município de Acrelândia, Acre, Brasil. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2008;11:241–251. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silveira FT, Lainson R, Corbett CE. Clinical and immunopathological spectrum of American cutaneous leishmaniasis with special reference to the disease in Amazonian Brazil: a review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2004;99:239–251. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762004000300001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teles CB, Basano SA, Zagonel-Oliveira M, Campos JJ, Oliveira AF, Freitas RA. Epidemiological aspects of American cutaneous leishmaniasis and phlebotomine sandfly population, in the municipality of Monte Negro, State of Rondônia, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2013;46:60–66. doi: 10.1590/0037-868216062013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tojal da Silva AC, Cupolillo E, Volpini AC, Almeida R, Romero GA. Species diversity causing human cutaneous leishmaniasis in Rio Branco, state of Acre, Brazil. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11:1388–1398. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Valdivia HO, De Los Santos MB, Fernandez R, Baldeviano GC, Zorrilla VO, Vera H. Natural Leishmania infection of Lutzomyia (Trichophoromyia) auraensis in Madre de Dios, Peru, detected by a fluorescence resonance energy transfer-based real-time polymerase chain reaction. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87:511–517. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]