SUMMARY

Chagas disease (CD) is an endemic anthropozoonosis from Latin America of which the main means of transmission is the contact of skin lesions or mucosa with the feces of triatomine bugs infected by Trypanosoma cruzi. In this article, we describe the first acute CD case acquired by vector transmission in the Rio de Janeiro State and confirmed by parasitological, serological and PCR tests. The patient presented acute cardiomyopathy and pericardial effusion without cardiac tamponade. Together with fever and malaise, a 3 cm wide erythematous, non-pruritic, papule compatible with a "chagoma" was found on his left wrist. This case report draws attention to the possible transmission of CD by non-domiciled native vectors in non-endemic areas. Therefore, acute CD should be included in the diagnostic workout of febrile diseases and acute myopericarditis in Rio de Janeiro.

KEYWORDS: Chagas disease, Transmission, Triatoma vitticeps, Rio de Janeiro

RESUMO

A doença de Chagas é antropozoonose endêmica na América Latina que tem como principal mecanismo de transmissão humana o contato da pele lesada ou da mucosa com as fezes de triatomíneos infectados por Trypanosoma cruzi. Neste artigo descrevemos o primeiro caso de doença de Chagas aguda adquirida no Estado do Rio de Janeiro por transmissão vetorial com confirmação parasitológica, sorológica e pela PCR. O paciente apresentou miocardite aguda e derrame pericárdico de evolução benigna. Juntamente com as manifestações sistêmicas da fase aguda, foi notada pápula eritematosa de três cm de diâmetro compatível com chagoma em punho esquerdo. Este relato de caso chama a atenção para a possibilidade de transmissão da doença de Chagas por vetores nativos não domiciliados e em áreas consideradas indenes. Portanto, a doença de Chagas aguda deve ser incluída entre os diagnósticos diferenciais de doenças febris e miopericardites agudas no Rio de Janeiro.

INTRODUCTION

Chagas disease (CD) is an endemic anthropozoonosis from Latin America of which the main mechanism of transmission is the contact of skin lesions or mucosa with the feces of triatomine bugs infected by Trypanosoma cruzi 3. Significant changes in CD epidemiology in endemic countries occurred after widespread efforts to control the main domiciled vectors (Triatoma infestans and Rhodnius prolixus) and improvement in blood banking quality programs4 , 16 , 19. In 2006, Brazil was certified by WHO as an area free of CD vectorial transmission by T. infestans 19 , 24. Although the prevalence of CD has decreased in the last decades, a recent meta-analysis estimated CD prevalence in Brazil to be near 2.4% or about 4.6 million Brazilians infected by T. cruzi 15. However, other transmission mechanisms may keep CD as a public health problem such as the ingestion of food contaminated with T cruzi, causing outbreaks of acute CD and transmission by native vectors in different areas of Brazil1 , 3 , 5 , 12 , 14 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 27 , 28.

Rio de Janeiro State (RJ) was always considered free of CD vectorial transmission with few old reports of domiciled T. infestans 2 , 11 , 25. Most of the eight vector species found in RJ are sylvatic, living in the Atlantic Forest and rarely found inside human habitations or in the peridomicile9.

However, T. vitticeps may be attracted to lights and invade human habitations in RJ rural areas7 , 8 , 11 , 13 , 14 , 21.

In this study, we report the first acute CD case acquired by vector transmission in RJ and confirmed by parasitological, serological and PCR tests. The patient presented acute cardiomyopathy and pericardial effusion without cardiac tamponade. Together with fever and malaise, an indurated, erythematous, and swollen skin lesion compatible with a "chagoma" was found on his left wrist20. This case report draws attention to the possible transmission of CD by non-domiciled native vectors in non-endemic areas where enzootic cycles in the peridomicile may contribute to CD human cases21. Therefore, acute CD should be included in the diagnostic workout of febrile diseases and acute myopericarditis in RJ.

CASE REPORT

A forty-seven-year-old white man born in the city of Rio de Janeiro and resident in the Engenho de Dentro neighborhood, in the city of Rio de Janeiro, was referred to the outpatient service of the Instituto Nacional de Infectologia Evandro Chagas (INI) with a one-month history of headache and daily remittent high fever (40 ºC). The symptoms started some days after returning from his country house located 100 km south of RJ, in the municipality of Mangaratiba. Over the last month, he went to other outpatient services where dengue, urinary infection, acute toxoplasmosis, tuberculosis, and HIV infection were ruled out. He was referred to our institution for malaria testing. Thick blood smear examination was negative for Plasmodium spp., but positive for T. cruzi trypomastigotes (Fig. 1A). On his epidemiological history, the patient denied knowing triatomine bugs, having received any blood transfusion or organ transplant, or having traveled outside RJ. However, there were fruit trees surrounding his country house, and he used to sleep in hammocks on the porch every weekend.

Fig. 1. A. Walker-stained thick blood smear positive for T. cruzi trypomastigotes (1000x). B. A 3 cm wide erythematous papule on the left wrist compatible with "chagoma".

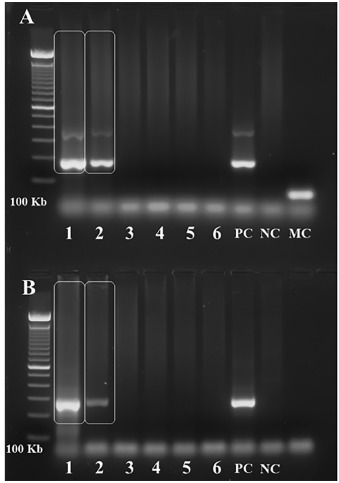

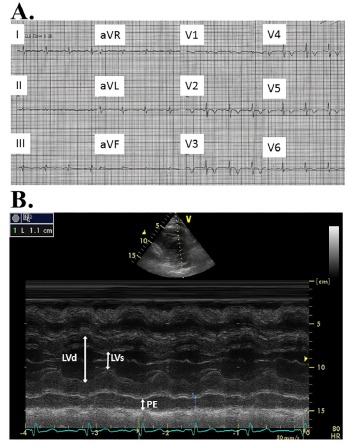

Examination was remarkable for high temperature (38 ºC), one cm rubbery, non-tender, freely movable bilateral occipital and right submandibular lymph nodes, and a three cm wide erythematous nonpruritic papule on his left wrist (Fig. 1B). Vital signs: heart rate 86 beats per minute, blood pressure 130⁄80 mmHg, weight 90 kg. The patient was alert, without respiratory distress, and with unremarkable respiratory, cardiovascular, and abdominal physical examination. Blood work revealed mild anemia, leukocytosis, and neutrophilia; high erythrocyte sedimentation rate (50 mm⁄h); a positive IgG indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) test for CD (1:1,280) and a negative enzymelinked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for CD. ELISA became positive (index of reactivity 1.3) on the fifth test obtained fifteen days after the first blood work, while IIF was strongly reactive (1:5,120) in the same blood sample. Hemoculture and PCR (Satellite DNA and kDNA) were positive for T. cruzi (Fig. 2). PCR was performed as previously described17. Electrocardiogram (ECG) showed sinus rhythm, incomplete right bundle branch block, low voltage complexes on the frontal plane and primary repolarization changes in anterior and inferior leads (Fig. 3A). Echocardiogram (ECO) revealed normal chamber diameters and left ventricular systolic function, left ventricular delayed relaxation and moderate pericardial effusion with no signs of restriction to diastolic filling of the heart (Fig. 3B). Those findings were considered compatible with acute myocarditis18. The patient started treatment with benznidazole (BZN) 300 mg/d, and seven days later the fever resolved. However, after 12 days of BZN treatment, the thick blood smear examination remained positive for T. cruzi and BZN dose was increased to 500 mg/d. Three days later the thick blood smear examination became negative for T. cruzi. The patient presented a mild transitory exanthema during BZN treatment. BZN treatment was discontinued after 60 days of treatment. The ECG and ECO findings normalized within 60 days of BZN treatment. A 5-fold decrease in serologic titers was observed four months after the end of BZN treatment.

Fig. 2. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) for T. cruzi . Positive result for T. cruzi satellite DNA (A.) and kDNA (B.) in the first two slots of both agarose gels depicted in the figure. The first slot corresponds to the collection made on the 13thday of BZN treatment, second slot on the 20thday, third slot on the 27th day, fourth slot on the 34th day, and fifth slot on the 41st day of BZN treatment. The sixth slot represents the sample collected four days after BZN was discontinued. PC = positive control; NC = negative control; MC = mix control (negative control: master mix devoid of DNA). PCR was performed as previously described17.

Fig. 3. A. Electrocardiogram. The electrocardiogram depicts sinus rhythm, incomplete right bundle branch block, low voltage complexes in the frontal plane and primary repolarization changes in anterior and inferior leads. B. Echocardiogram. Two-dimensional-guided M-mode echocardiogram at the papillary muscle level. Note the normal LV chamber diameters and systolic function, and moderate pericardial effusion. LV= left ventricle; LVd = LV end-diastolic diameter; LVs = LV end-systolic diameter; PE = pericardial effusion.

According to the epidemiological investigation carried out at Mangaratiba after the case was notified to the RJ vigilance authorities, T. cruzi was found in the feces of an adult specimen of Triatoma tibiamaculata collected inside of one of the houses and T. cruzi infection was identified in sylvatic rodents and dogs (GIORDANO-DIAS 2012, unpublished results).

DISCUSSION

The late diagnosis of acute CD in this case is at least in part due to the fact that CD was never considered endemic in RJ. There are few reports of domiciled triatomines in RJ but the domestic invasion of human habitations by sylvatic triatomines is frequent2 , 7 , 8 , 11 , 13 , 14 , 21. Although domestic invasion by T. tibiamaculata in RJ is very rare, this triatomine has been found frequently inside homes in the Bahia State6 , 10. Moreover, T. tibiamaculata was associated with the acute CD outbreak that occurred in the southern Brazilian Santa Catarina State in 2005, due to the consumption of contaminated sugarcane juice 9 , 27. The contact of the vector with the patient most likely occurred on the porch of the house where the patient used to sleep in a hammock every night. On the other hand, T. vitticeps infected by T. cruzi is often found inside human habitations not only in RJ but in the Espirito Santo and Minas Gerais States8 , 21 , 22 , 26. Although T. vitticeps has never been reported in Mangaratiba, this triatomine was already found in many other municipalities of RJ21. T. cruzi transmission cycles found in the peridomicile in RJ may contribute to the occurrence of CD autochthonous cases in RJ21.

Acute CD is usually asymptomatic, but even when symptoms occurs the disease has a good prognosis19. In this case, the "chagoma" in the left wrist appeared some days before the beginning of fever, as expected according to the described evolution of acute CD cases19. Myocarditis and pericarditis presented a benign evolution, and were resolved after BZN treatment. Meningoencephalitis, which is more prevalent among children under 2 years old, was not observed in this case20. This is the first study to report that a thick blood smear became negative for T. cruzi within 15 days of BZN treatment. This case also illustrated that BZN doses above 300 mg⁄d may be necessary in adults weighing more than 60 kg. In this case, while IIF was already strongly positive in the presentation, ELISA was much less effective to confirm the diagnosis. The different diagnostic effectiveness between these two tests may be due to the use of recombinant antigens in the ELISA with higher affinity for the IgG produced in the chronic phase than in the acute phase of CD29. From 2007 to 2011, 34 vector-transmitted acute CD cases were reported in Brazil outside the Amazon region1 , 28. However, the actual incidence of vector-transmitted acute CD cases must be higher due to several reasons: acute T. cruzi infection is usually asymptomatic, laboratory tests failure to diagnose acute CD cases, and underreporting1 , 19. It is estimated that only 15% of vector-borne acute CD cases are reported1. The case reported in this article draws attention to the challenging control of CD transmission by non-domiciled sylvatic vectors that occasionally invade houses attracted by artificial light sources1.

Acute CD is unlikely to become common in RJ as there are no domiciled vectors in RJ and T. vitticeps, which may invade human habitations in several RJ municipalities, has low vector potential due to the long interval between feeding and defecation7 , 22. However, the presence of T. cruzi sylvatic cycles in RJ allows sporadic autochthonous human cases in the State. Thus, CD must be included in the diagnostic workout of febrile diseases and myopericarditis in RJ.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful for the information regarding the epidemiological investigation carried out in Mangaratiba provided by the coordination of Health Surveillance of the Health Secretariat of the Rio de Janeiro State.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abad-Franch F, Diotaiuti L, Gurgel-Gonçalves R, Gürtler RE. On bugs and bias: improving Chagas disease control assessment. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2014;109:125–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aragão MB, Souza SA. Triatoma infestans colonizando em domicílios da Baixada Fluminense, estado do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 1971;5:115–121. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coura JR. Chagas disease: what is known and what is need: a background article. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2007;102(Suppl 1):113–122. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762007000900018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dias JCP, Silveira AC, Schofield CJ. The impact of Chagas disease control in Latin America: a review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97:603–612. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762002000500002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dias JP, Bastos C, Araújo E, Mascarenhas AV, Martins Netto E, Grassi F. Acute Chagas disease outbreak associated with oral transmission. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2008;41:296–300. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822008000300014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dias-Lima AG, Sherlock IA. Sylvatic vectors invading houses and the risk of emergence of cases of Chagas disease in Salvador, State of Bahia, Northeast Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2000;95:611–613. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762000000500004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferreira E, Souza OS, Fonseca M, Filho, Rocha I. Nota sobre a distribuição geográfica do Triatoma vitticeps Stal, 1859 (Hemiptera, Reduviidae) no estado do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Rev Bras Malariol D Trop. 1986;38:11–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonçalves TCM, Oliveira E, Dias LS, Almeida MD, Nogueira WO, Pires FDA. An investigation on the ecology of Triatoma vitticeps (Stal, 1859) and its possible role in the transmission of Trypanosoma cruzi, in the locality of Triunfo, Santa Maria Madalena municipal district, state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1998;93:711–717. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761998000600002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gurgel-Gonçalves R, Galvão C, Costa J, Peterson AT. Geographic distribution of Chagas disease vectors in Brazil based on ecological niche modeling. J Trop Med. 2012;2012:1–15. doi: 10.1155/2012/705326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gurgel-Gonçalves R, Galvão C, Mendonça J, Costa-Neto EM. Guia de triatomíneos da Bahia. Feira de Santana: Ed. UEFS/Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lent H. Transmissores da moléstia de Chagas no estado do Rio de Janeiro. Rev Fluminense Med. 1942;7:151–162. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lima AFR, Jeraldo VLS, Silveira MS, Madi RR, Santana TBK, Melo CM. Triatomines in dwellings and outbuildings in an endemic area of Chagas disease in northeastern Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2012;45:701–706. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822012000600009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lorosa ES, Santos CM, Juberg J. Foco da doença de Chagas em São Fidélis, no estado do Rio de Janeiro. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2008;41:419–420. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822008000400020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorosa ES, Valente MVM, Cunha V, Lent H, Juberg J. Foco da doença de Chagas em Arcádia, estado do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2003;98:885–887. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762003000700004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martins-Melo FR, Ramos AN Jr, Alencar CH, Heukelbach J. Prevalence of Chagas disease in Brazil: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Trop. 2014;130:167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moncayo A, Silveira AC. Current epidemiological trends for Chagas disease in Latin America and future challenges in epidemiology, surveillance and health policy. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104(Suppl 1):17–30. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762009000900005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moser DR, Kirchhoff LV, Donelson JE. Detection of Trypanosoma cruzi by DNA amplification using the polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1477–1482. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.7.1477-1482.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parada H, Carrasco HA, Añez N, Fuenmayor C, Inglessis I. Cardiac involvement is a constant finding in acute Chagas' disease: a clinical, parasitological and histopathological study. Int J Cardiol. 1997;60:49–54. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(97)02952-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rassi A Jr, Rassi A, Marin-Neto JA. Chagas disease. Lancet. 2010;375(9723):1388–1402. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60061-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rassi A Jr, Rassi A, Marcondes de Rezende JM. American trypanosomiasis (Chagas disease) Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2012;26:275–291. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sangenis LHC. Doença de Chagas em naturais do estado do Rio de Janeiro: aspectos clínico-epidemiológicos, caracterização molecular parasitológica e estudo ecoepidemiológico dos casos autóctones . Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Oswaldo Cruz/Fundação Oswaldo Cruz; 2013. Tese. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santos CB, Leite GR, Ferreira GEM, Ferreira AL. Infecção natural de Triatoma vitticeps (Stal, 1859) por flagelados morfologicamente semelhantes a Trypanosoma cruzi (Chagas, 1909) no estado do Espírito Santo. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2006;39:89–91. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822006000100019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarquis O, Sposina R, Oliveira TG, Mac Cord JR, Cabello PH, Borges-Pereira J. Aspects of peridomiciliary ecotopes in rural areas of Northeastern Brazil associated to triatomine (Hemiptera, Reduviidae) infestation, vectors of Chagas disease. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2006;101:143–147. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762006000200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silveira AC, Dias JCP. O controle da transmissão vetorial. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2011;44:52–63. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822011000800009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silveira AC, Sakamoto T, Faria-Filho OF, Gil HSG. Sobre o foco de triatomíneos domiciliados na Baixada Fluminense. Rev Bras Malariol D Trop. 1982;34:50–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Souza RCM, Diotaiuti L, Lorenzo MG, Gorla DE. Analysis of the geographical distribution of Triatoma vitticeps (Stal, 1859) based on data species occurrence in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Infect Genet Evol. 2010;10:720–726. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steindel M, Pacheco LK, Scholl D, Soares M, de Moraes MH, Eger I. Characterization of Trypanosoma cruzi isolated from humans, vectors, and animal reservoirs following an outbreak of acute human Chagas disease in Santa Catarina State, Brazil. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;60:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vinhaes MC, Oliveira SV, Reis PO, Sousa ACL, Silva RA, Obara MT. Assessing the vulnerability of Brazilian municipalities to the vectorial transmission ofTrypanosoma cruzi using multi-criteria decision analysis. Acta Trop. 2014;137:105–110. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Umezawa ES, Luquetti AO, Levitus G, Ponce C, Ponce E, Henriquez D. Serodiagnosis of chronic and acute Chagas' disease with Trypanosoma cruzi recombinant proteins: results of a collaborative study in six Latin American countries. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:449–452. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.1.449-452.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]