Abstract

Background:

The term ‘Medically Unexplained Symptoms’ (MUS) is used by health professionals and researchers to refer to persistent bodily complaints, including pain and discomfort.

Aims:

This study explores the views held by a lay sample on the clinical terminology used to describe ‘MUS’, to ascertain reasons for particular preferences and whether preferences differ between individuals who experience more somatic symptoms.

Design and methods:

A sample (n = 844) of healthy adults completed an online survey, which included a questionnaire measuring somatic symptoms (Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15)) and a question about their preferences for terminology used to describe MUS.

Results:

Of 844 participants, 698 offered their preferences for terminology. The most popular terms were ‘Persistent Physical Symptoms’ (20%) and ‘Functional Symptoms’ (17%). ‘MUS’ (15%), ‘Body Distress Disorder’ (13%) and ‘Complex Physical Symptoms’ (5%) were less popular. And 24% indicated no preference, but high PHQ-15 scorers were more likely to express preferences than low scorers.

Conclusion:

Persistent Physical Symptoms and Functional Symptoms are more acceptable to this sample of healthy adults than the more commonly used term ‘MUS’.

Keywords: Medically Unexplained Symptoms, somatoform disorders, pain, Functional Symptoms, Persistent Physical Symptoms

Introduction

The term ‘Medically Unexplained Symptoms’ (MUS) or ‘persistent bodily complaints for which adequate examination does not reveal sufficiently explanatory structural or other specified pathology’1 is commonly used to describe people with pain and discomfort in general practice and secondary care.2,3 It is used as the generic term to include ‘non cardiac chest pain’, ‘irritable bowel syndrome’ and ‘fibromyalgia’.4,5

Assuming that a generic term is useful, and even here there is much debate,1,6 it needs to be carefully considered. Patient engagement is important and labels should be acceptable, meaningful and relevant to patients.2 The term ‘MUS’ has been criticised in terms of its ambiguity; a ‘negative label’ offers no insight into the cause, duration, severity or significance of symptoms. It is arguably misleading and unhelpful when applied to patients with chronic pain.7,8 The term reinforces ‘mind–body dualism’9 and may not acknowledge the diverse biological processes often associated with common physical symptoms10 or the interrelationship between psychological, social and physical states. The term ‘MUS’ prioritises medical explanation despite evidence suggesting this is less predictive of long-term outcome than symptom profile and psychological correlates.11–13 The term ‘MUS’ may appear to be an objective and straightforward term to describe symptoms that have not been medically explained, but ‘MUS’ historically has strong dualistic connotations, having been developed within psychiatry to refer to ‘physical symptoms caused by psychological distress’.14 Such associations may not be immediately clear to the general public.

Psychiatric classification systems (International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)) have offered alternative labels, such as ‘somatisation’, ‘unexplained somatic complaints’, ‘somatoform disorders’ and ‘somatisation disorder’. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) has recently replaced the diagnosis of ‘MUS’ and now refers to ‘Somatic Symptom Disorder’ (SSD). A diagnosis of SSD does not require symptoms to be ‘medically unexplained’ but instead refers to any persistent and clinically significant somatic complaints with associated excessive thoughts, feelings and behaviours. In the DSM-5 criteria, SSD as a mental disorder is not dependent upon whether or not a medical cause is demonstrable, and patients must also meet all the other requisite criteria for diagnosis.15

Creed et al.9 suggested 10 criteria for evaluating suitable terms. These included the following: acceptability to patients and professionals; avoiding dualism; having relevance to established disease; being a stand-alone diagnosis; having a clear core theoretical concept; facilitating multidisciplinary treatment; having cross-cultural relevance; being neutral with regard to pathology and aetiology and having an acceptable acronym. Using these criteria, Creed et al.9 appraised eight common terms and concluded that ‘functional somatic disorder or syndrome’ and ‘bodily distress disorder’ were most suitable; ‘MUS’ failed on most criteria.

Few studies have examined how laypeople view this terminology. Stone et al.16 assessed to what extent service users found certain terms (such as hysteria) ‘offensive’, but they did not ask for alternative viewpoints. Other studies have focused upon specific labels, such as chronic fatigue syndrome,17 but patients already labelled may have developed bias from experiences of healthcare,17 and no studies have explored how laypeople with and without somatic symptoms view the terminology used in this area.

Aim

This study aimed to assess the following:

The preferences of a healthy adult sample for the term used to describe physical symptoms with no clear physical cause;

Whether people with more somatic symptoms (high and low Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15) scores) differed in their preferences.

Methods

Participants

From December 2011 to February 2012, 844 healthy individuals consented to take part in an online survey. The sample was recruited via circular emails sent to staff and students at two universities, on social networking sites and to members of a volunteer database of healthy adults (‘Mindsearch’). Of these, 598 (65% of the total sample) provided complete data. Participants were excluded if they had a current diagnosis of a severe physical health problem or mental illness or were under 18 years of age. The study was given ethical approval by King’s College London University, number PNM/12/13–1.

Procedure and materials

Participants completed a questionnaire including demographic questions and the PHQ-15, which assesses the severity (0 to 2 scale) of 15 somatic symptom clusters common in outpatient settings,18 and a multiple-choice preference question:

We are interested in your views about the terms used to describe common physical symptoms that persist when no clear physical cause is found. If you had a physical symptom, such as fatigue or pain that persisted and was found by doctors not to be caused by a particular disease, which of the following do you think should be used to describe the symptoms?

Participants could choose one of the seven options: ‘Complex Physical Symptoms’, ‘Functional Symptoms’, Bodily Distress Disorder’, ‘Medically Unexplained Symptoms’, ‘Persistent Physical Symptoms’, ‘Other’ (stating what in an open text box) or ‘No Preference’. The options did not include terms that failed to meet Creed’s 10 criteria9 (i.e. ‘somatoform disorder’, ‘symptom defined illness’, ‘somatic symptom disorder’ and ‘psychosomatic disorder’). However, MUS was included due to its current common usage. Participants could then explain their choice or offer further opinions in an open text box.

Analysis

Participant demographics and descriptive statistics of preferred terms were analysed using SPSS version 21.0. The open text answers were subjected to content analysis.

Results

The mean age was 27 years (standard deviation (SD) 9.6 years) (range 18–83 years), 75% were female and the majority (77%) were White. The mean score on the PHQ-15 was 6.85 (SD 4.23) with 75% scoring below the suggested clinical cut-off of 10.19

Preferred terms

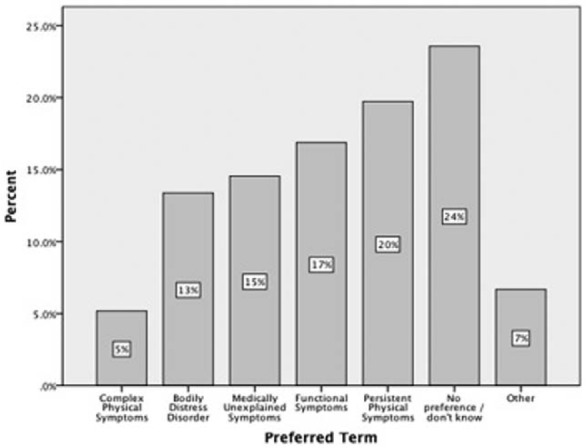

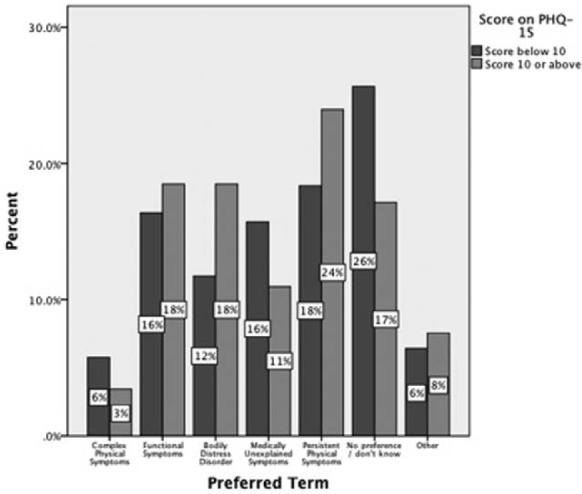

In total, 141 (24%) participants indicated that they had no preference. The most popular term was ‘Persistent Physical Symptoms’ (20%), followed by ‘Functional Symptoms’ (17%). Less popular were ‘Medically Unexplained Symptoms’ (15%), ‘Bodily Distress Disorder’ (13%) and ‘Complex Physical Symptoms’ (5%) (Figure 1). There were no significant differences in preferences for gender, age, ethnicity nor educational level. There was a non-significant trend for high PHQ-15 scorers, compared to low PHQ-15 scorers, to show greater preference for ‘Persistent Physical Symptoms’ (24%) and ‘Bodily Distress Disorder’ (18%) and less preference for ‘Medically Unexplained Symptoms’ (11%) (χ2 = 12.32, p = .055). High PHQ-15 scorers were more likely to express an opinion, with only 17% having ‘no preference’, compared to 26% of low scorers (see Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Preferred terms reported by the overall sample.

Figure 2.

Preferred terms demonstrated by high versus low PHQ-15 scorers.

PHQ-15: Patient Health Questionnaire-15.

Qualitative data

Opinions about terms and themes offered by 141 participants are shown in Table 1. Many participants viewed labels as unhelpful as they reinforced ‘mind–body dualism’. More useful terms were those that were transparent, clear and easily explained to patients, and demonstrate how psychological, emotional and physical factors interact. Healthcare professionals were deemed to have a moral and professional duty to use terms that enhance patients’ understanding and self-care. A number of participants discussed the potential risk of using diagnostic labels in this area and how easily a term such as ‘MUS’ could be conflated with pejorative meanings, which might be easily discovered by patients (e.g. using Internet searches).

Table 1.

Comments about terminology made by participants in response to open question.

| Term | (n) | Advantages of using this terminology | (n) | Disadvantages of using this terminology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complex physical symptoms | 1 | Accounts for different causes and symptoms | 4 | Sounds like you are ‘being humoured’ |

| Risky as is unconfirmed Does not account for symptoms that | ||||

| are not ‘complex’ (in one area) | ||||

| Functional symptoms | 6 | Least imposing/distressingMost realistic if no diseaseAcknowledgement of impact on lifeFunctional is more accurateHelpful focus on ‘no disease’ | 4 | Does not confirm what is happening |

| May be confusingImplies symptoms are ‘made up’ | ||||

| Bodily distress disorder | 6 | Highlights psychological impactExplains real and unpleasant sensations can result from stressAppropriate if no diseaseRelief as like a ‘diagnosis’ | 9 | Potentially worrying due to negative connotations |

| Overcomplicated and does not acknowledge possible causes | ||||

| Suggests you are malingering | ||||

| ‘Distress’ too emotive | ||||

| ‘Disorder’ too frightening | ||||

| Medically Unexplained Symptoms | 13 | Accurate and truthful (as the medical profession does not know all the answers)UK specific as medical treatment is usual course and will not workLeast emotive, most objective phraseNot caused by diseaseLeast judgmentalBalanced – not oversimplified not overcomplicatedMay be reasonable for someClearer for the layperson | 15 | Frustrating; does not acknowledge a concrete cause or explanation |

| Not culturally transferable | ||||

| ‘Doctors code for “all in your head”’ or fictional problems. | ||||

| Belittles, implicitly blames patient | ||||

| Possibly incorrect if there is a medical explanation | ||||

| Suggests medicine cannot treat physiological problems | ||||

| Not reassuring or encouraging | ||||

| Feels like things are hopeless, untreatable and uncontrollable | ||||

| Doctor sounds incompetent or ‘given up trying to help’ | ||||

| Suggests ‘medical explanation’ is important | ||||

| Persistent Physical Symptoms | 5 | By implying it is an ongoing condition, it will not be ignored Shows the cause is unknownTransparent description, less likely to raise concernsGrounded and does not blame the person for the symptoms | 2 | Oversimplifies problems |

| Does not acknowledge impact of symptoms on life | ||||

| Does not suggest a cause | ||||

| Fails to account for symptoms that are not completely ‘physical’ (e.g. anxiety) | ||||

| Psychosomatic/psychogenic | 13 | Acknowledges that psychological and physical factors work both ways | 3 | Implies that any symptoms not understood by contemporary medicine are ‘psychosomatic’ |

| May discredit people’s symptoms | ||||

| Psychological/emotional/stress related | 24 | Term should show psychological factors play a role if they doAcknowledges the relationship of stress and physical symptomsOften are psychological causes to unpleasant sensationsReminds the patient that there may not be a physical cause,reducing impact of symptomsAids normalisation, acceptanceMention autonomic nervous systemReduces over-medicalisation | 5 | Suggestion of psychologically mediated symptoms feels like you are being ‘fobbed off’ |

| Increases risk of trivialising and under-investigation of symptoms | ||||

| Risk of labelled a hypochondriac | ||||

| ‘Stress’ feels like a ‘cop out’ | ||||

| Not all such symptoms are related to stress | ||||

| Any term with ‘disorder’ or ‘disease’ | 1 | This title makes it seem more legitimate | 8 | May increase anxiety and the idea you cannot be cured |

| Not always true | ||||

| Negative connotations for a common experience | ||||

| Not all embodied experiences are explained by medical discourse | ||||

| It is only a disorder when it interferes with daily function | ||||

| Increases risk of stigma | ||||

| Any term with ‘symptoms’ | 4 | Recognition of symptoms even if doctor has not found a causeShows symptoms as part of a continuum and thus avoids overstating importance | 2 | Too vague |

| ‘Symptoms’ implies an illness, which makes no sense if there is no diagnosis | ||||

| Use of diagnostic terminology | 3 | A diagnostic ‘hook’ makes one feel understood that things are controllable or treatable thus helping recovery | 2 | Official medical names may make suggest the doctor will ‘fix them’ |

| Any fancy name will soon reveal the truth anyway | ||||

| Call things what they are, ‘fancy names’ just label patients and suggests things are complex and unsolvable |

Discussion

This study explored the views held by a lay sample on common terms describing persistent bodily pain and discomfort. The sample of relatively young adults that reflects the demographic characteristics common among people reporting ‘MUS’, that is, including a large proportion of younger, female, highly educated individuals,3 is a strength of this study. Approximately one-quarter reported ‘no preference’ for terminology, which may suggest a lack of relevance in this relatively healthy sample. Of the terms suggested, ‘Persistent Physical Symptoms’ was preferred, followed by ‘Functional Symptoms’. ‘Medically Unexplained Symptoms’ was less popular, particularly among individuals scoring high on the PHQ-15, who were less likely to show ‘no preference’ and who preferred ‘Persistent Physical Symptoms’, followed by ‘Bodily Distress Disorder’ and ‘Functional Symptoms’. The results did not vary with age, gender, educational level or ethnicity.

These are important findings considering how commonly the term ‘MUS’ is used by clinicians and academics. A possible alternative endorsed in this study is ‘Persistent Physical Symptoms’, which is a transparent description of the symptoms experienced. The finding that ‘Functional Symptoms’ is the second preferred term is consistent with a previous report that service users found this term ‘least offensive’.16 ‘Functional Symptoms’ can imply that symptoms arise from a disturbance in bodily functioning,20 and participants felt that ‘functional’ acknowledges the impact of symptoms upon one’s life.

Participants referred to helpful terms as those that avoid mind–body dualism, have cross-cultural relevance and include the physical as well as the emotional factors in aetiology, in line with critiques in the literature.9 They decried jargon, over-medicalisation and emotive terms and viewed ‘unexplained symptoms’ as unhelpfully culturally specific and implying medical incompetence and hopelessness. However, some participants thought ‘MUS’ truthful and non-judgemental. Terms including ‘disorder’ or ‘disease’ were regarded as emotive or stigmatising; however, they could also help to legitimise symptoms. Participants preferred terms that identified the interaction of different factors in precipitating and perpetuating physical symptoms, that is, minimising mind–body dualism by offering a ‘biopsychosocial’ model of illness.

Limitations

We did not include ‘SSD’ since the survey was carried out before the publication of the DSM-5. The term did not meet the criteria proposed by Creed9, who states that ‘somatic symptom disorder is not a term that is likely to be embraced enthusiastically by doctors or patients; it has an uncertain core concept, dubious wide acceptability across cultures and does not promote multidisciplinary treatment’ (p. 5). It was therefore not included in this survey. However, with hindsight, it would have been useful to examine preferences for this term now that it is included in DSM-5. The sample is mainly of White British ethnicity; while this may be a minor limitation as there may be few differences between ethnicities in terms of ‘somatization’,21 more research is needed to explore preferences for terms among people of a range of ethnicities.

Conclusion

A lay-population did not endorse MUS as a preferred term, and although 25% had no preference, the most popular term was ‘Persistent Physical Symptoms’, followed by ‘Functional Symptoms’. We suggest that the use of ‘MUS’ should be reconsidered. If clinicians and academics are to continue using a generic term for these symptom clusters, patients must be involved in the development of a relevant, helpful, transparent term that encapsulates a biopsychosocial, multidisciplinary approach to health.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Henningsen P, Zipfel S, Herzog W. Management of functional somatic syndromes. Lancet 2007; 369: 946–955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Van Ravenzwaaij J, olde Hartman TC, van Ravesteijn H, et al. Explanatory models of medically unexplained symptoms: a qualitative analysis of the literature. Ment Health Fam Med 2010; 7: 223–231. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nimnuan T, Hotopf M, Wessely S. Medically unexplained symptoms: an epidemiological study in seven specialties. J Psychosom Res 2001; 51: 361–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fink P, Schroder A. One single diagnosis, bodily distress syndrome, succeeded to capture 10 diagnostic categories of functional somatic syndromes and somatoform disorders. J Psychosom Res 2010; 68: 415–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Department of Health. Improving Access to Psychological Therapies. Medically unexplained symptoms positive practice guide, 2008, www.iapt.nhs.uk

- 6. Wessely S, White PD. There is only one functional somatic syndrome. Br J Psychiatry 2004; 185: 95–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tracey I, Bushnell C. How neuroimaging studies have challenged us to rethink: is chronic pain a disease? J Pain 2009; 10(11): 1113–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain 2011; 152(3): 2–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Creed F, Guthrie E, Fink P, et al. Is there a better term than ‘Medically unexplained symptoms’? J Psychosom Res 2010; 68: 5–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rief W, Barsky AJ. Psychobiological perspectives on somatoform disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2005; 30: 996–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tomenson B, Essan C, Jacobi F, et al. Total somatic symptom score as a predictor of health outcome in somatic symptom disorders. Br J Psychiatry 2013; 203: 373–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kisely S, Simon G. An international study comparing the effect of medically explained and unexplained somatic symptoms on psycho-social outcome. J Psychosom Res 2006; 60: 125–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jackson J, Fiddler M, Kapur N, et al. Number of bodily symptoms predicts outcome more accurately than health anxiety in patients attending neurology, cardiology, and gastroenterology clinics. J Psychosom Res 2006; 60: 357–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Department of Health. Talking therapies: a four year plan, 2011, www.iapt.nhs.uk

- 15. American Psychiatric Association. Somatic symptom disorder fact sheet, 2013, www.dsm5.org

- 16. Stone J, Wojcik W, Durrance D, et al. What should we say to patients with symptoms unexplained by disease? The ‘number needed to offend’. BMJ 2002; 325: 1449–1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jason LA, Holbert C, Torres-Harding S, et al. Stigma and the term Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: results of surveys on changing the name. J Disabil Pol Stud 2004; 14(4): 222–228. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med 2002; 64(2): 258–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Körber S, Frieser D, Steinbrecher N, et al. Classification characteristics of the Patient Health Questionnaire-15 for screening somatoform disorders in a primary care setting. J Psychosom Res 2011; 71(3): 142–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mayou R, Farmer A. Functional somatic symptoms and syndromes. BMJ 2002; 325: 265–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Busaidi ZQ. The concept of somatization: a cross-cultural perspective. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 2010; 10(2): 180–186. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]