Abstract

Introduction:

The first hospital palliative care unit (HPCU) in Iran (FARS-HPCU) has been established in 2008 in the Cancer Institute, which is the largest referral cancer center in the country. We attempted to assess the performance of the HPCU based on a comprehensive conceptual framework. The main aim of this study was to develop a conceptual framework for assessment of the HPCU performances through designing a value chain in line with the goals and the main processes (core and support).

Materials and Methods:

We collected data from a variety of sources, including international guidelines, international best practices, and expert opinions in the country and compared them with national policies and priorities. We also took into consideration the trend of the HPCU development in the Cancer Institute of Iran. Through benchmarking the gap area with the performance standards, some recommendations for better outcome are proposed.

Results:

The framework for performance assessment consisted of 154 process indicators (PIs), based on which the main stakeholders of the HPCU (including staff, patients, and families) offered their scoring. The outcome revealed the state of the processes as well as the gaps

Conclusion:

Despite a significant improvement in many processes and indicators, more development in the comprehensive and integrative aspects of FARS-HPCU performance is required. Consideration of all supportive and palliative requirements of the patients through interdisciplinary and collaborative approaches is recommended.

Keywords: Cancer, Conceptual framework, Hospital palliative care unit, performance assessment, Palliative care, Value chain

INTRODUCTION

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), “palliative care is an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual“.[1] Different levels of palliative care (PC) include hospital-based PC, home-based or community-based PC, and hospices.

Hospital palliative care unit (HPCU) is an inpatient unit within a general, secondary, or tertiary setting in the hospital, in which the patients are under the clinical direction of specialists within a PC team.[2] HPCU in a cancer center deals with complex physical, psychosocial. and spiritual needs of patients and their families and caregivers.[2,3] In coordination with community PC services, HPCU stabilizes patients’ symptoms and enable them to return home for further support.[4] A similar collaborative work between HPCU and hospices provides the end-of-life support for the terminal patients.

Based on the National Consensus Project Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care in the USA, hospital PCs is delivered through an interdisciplinary team consisting of physicians, nurses, and social workers with appropriate training and obtain certification. Also chaplains, rehabilitative experts, psychiatrists, and other professionals support and contribute as indicated. However, the staffing of a PC program will depend critically on the needs and capacities of the setting.[5]

Although PC is relatively new medical specialty in some developing countries, the number of specialists and programs has increased significantly in the last decade. According to a survey performed in 2010, majority of cancer centers in the US provide a PC service, although the levels of services and integration varied between different centers.[6] In developed countries, the PC unit widely integrated with other special care unit; however, this important integration is lacking in developing countries and remained to be addressed.[7]

A recent study introduced a feasible and efficient model in which PC could be delivered simultaneously with oncology care in anambulatory care setting.[8] In this model, specialist-level PC is delivered through a range of clinical models, including inpatient consultation services, dedicated in patient units, and outpatient practices.[8]

PC units for cancer patients have been recently started to work in Iran. HPCUs have been established in a few major cancer centers across the country. The cancer institute—the first cancer center in Iran—has set up a HPCU called “FARS” in 2008. It consists of an inpatient PC unit, a PC consultation unit, and an outpatient PC clinic. The inpatient PC unit, which is funded by donated money, provides services for 20 beds.

We aim to evaluate infrastructure and function of FARS-HPCU over the past 4 years. The main objective of this study was to develop a performance assessment framework for FARS-HPCU. This frame work can be implemented for establishment and evaluation of the HPCUs across Iran and other countries with similar healthcare system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The process indicators (PIs) for evaluation of HPCUs appropriated with the infrastructures and conditions of the country has been located. Thus, there might be different perceptions of HPCU based on the criteria used to define PIs.

In order to evaluate the performance of a HPCU, it is required to be assessed by three layers of the performance management model; conceptual, operational, and executive frameworks. First, we developed the conceptual framework of the assessment. This includes alignment of values (outcomes) and processes.

We have used the “value chain” concept to show the alignment between the processes of the unit with outcomes. The idea of value chain is originated from the process view of the organizations. A value chain is a chain of activities that an organization performs in order to deliver a valuable product or service. The value chain concept was first described and popularized by Michel Porter in 1980s and applied in health systems in 2009.[9]

In our case, a “value chain” is a chain of processes that a unit performs to deliver valuable services to the patients and their families. The primary activities that are required to meet the outcomes are called “core processes” and secondary activities include procurement, human resource management, technological development, and infrastructure are known as “support processes“. The core processes assure that the unit works effectively and the support process are responsible for the efficiency of the unit.

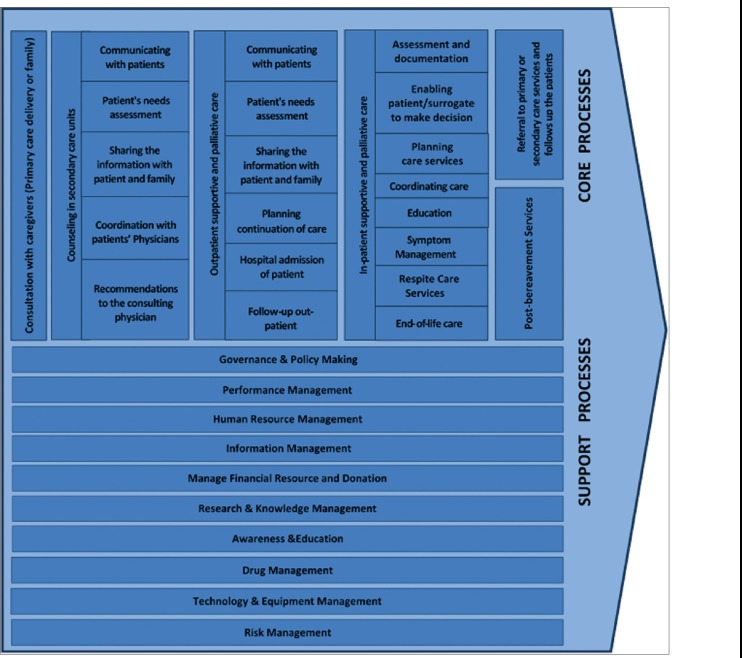

The conceptual framework that was designed for evaluation of FARS-HPCU performance includes a value chain, an outcome, and an inventory of 154 PIs covering the main processes in the chain. This framework was used to prepare the questionnaire and interviews [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Developing the conceptual framework in assessment of the FARS HPCU

We prepared the questionnaire in three phases. First, we performed an in-depth literature review. We included the recommendations of the WHO and other international associations such as International Association for Hospice and Palliative care (IAHPC), Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance (WPCA), Middle East Cancer Consortium (MECC), and African Palliative Care Association (APCA).[1,2,10,11,12]

Accordingly, the reports from several countries were reviewed systematically for comparative analysis. Developed and developing countries have been considered in this analysis. The best practices selected by the quality assurance organizations were used to define the PIs.[5,13,14,15]

Second, we adjusted the values and inventory of the PIs with policies and regulations such as the clinical governance and the hospital accreditation framework and guidelines.[16]

We also collected the opinions of the policy-makers in the ministry of health through two sessions of semistructured interviews. The questions were prepared to the outcome and value chain of an HPCU in a cancer center in Iran. The PIs were not considered in this interview. We further have reviewed the reports of the FARS-HPCU and setup interviews with the director of the Cancer Institute, founders, and head of the unit for achieving historical overview.

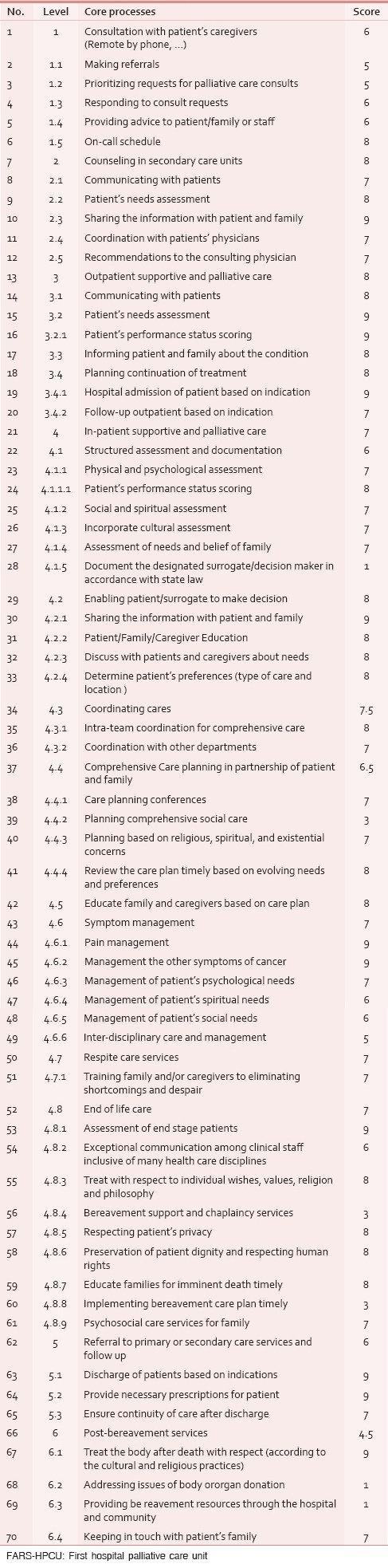

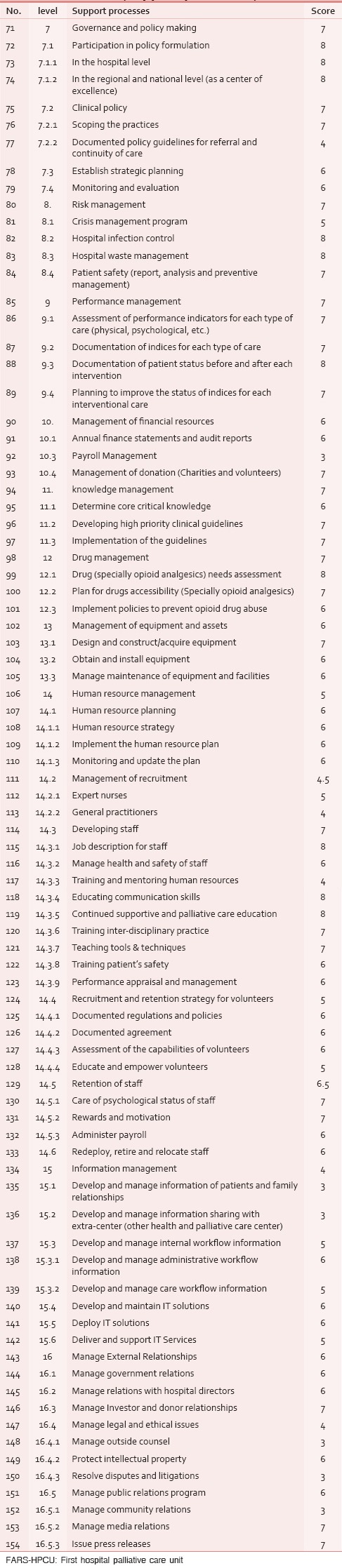

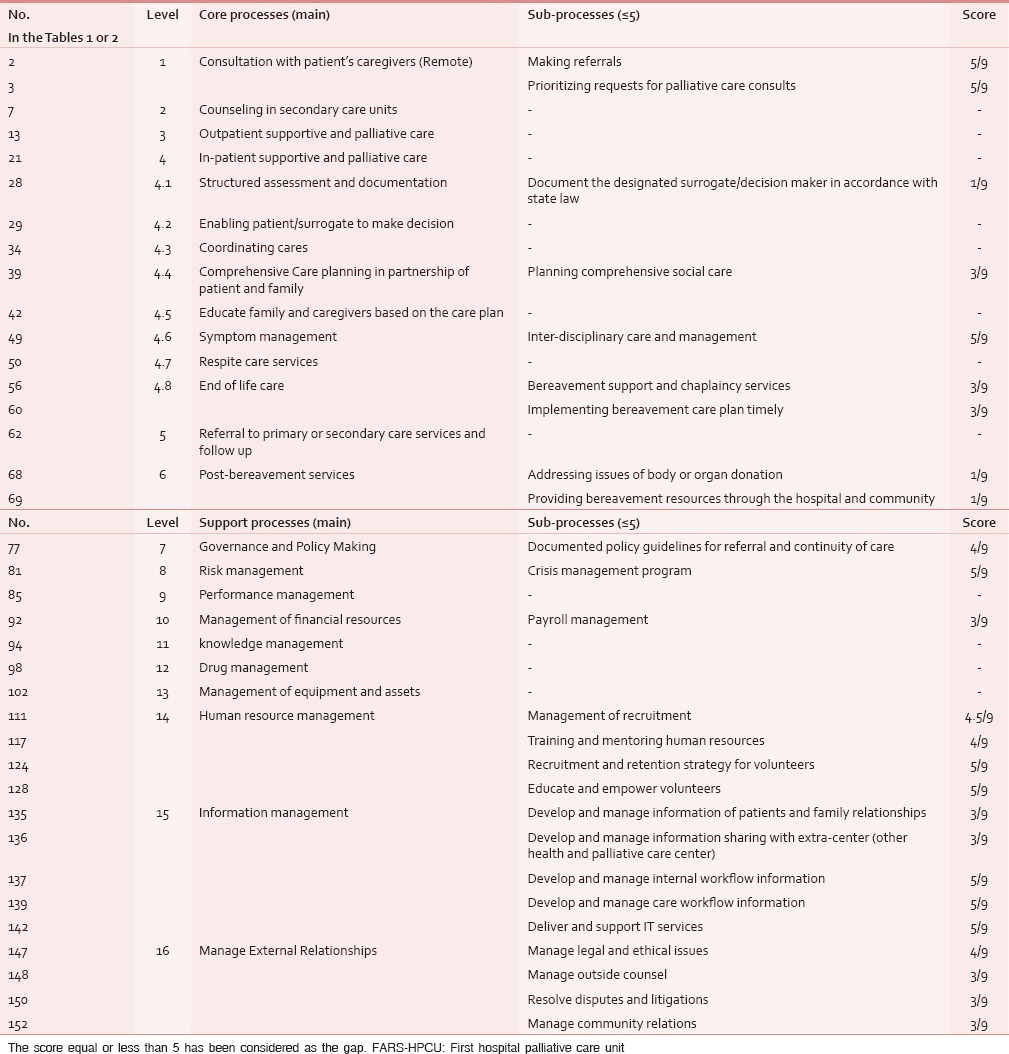

Finally, we obtained expert opinions about the outcome statements and inventory of PIs [Box 1]. A list of 197 PIs was asked in a questionnaire from the experts to select the most appropriate ones based on the relevance and feasibility. For each of the item, the answerers had three choices, “agree“, “not agree“, and “unsure“. We received 21 of 25 questionnaires and analyzed them, statistically. According to the answers, we have extracted 154 PIs in a comprehensive list. The processes of the method are illustrated in Figure 1. After preparing a comprehensive list of the core and support PIs, we asked the three categories of stakeholders to score each process status. Patients and families (n = 5), staff of FARS-HPCU (n = 3), and director of the FARS-HPCU answered a 154-item questionnaire from which 70items were about the core processes [Table 1] and 84items were about support processes [Table 2]. The patients and families only scored the core processes, but the other answerer scored both the core and support.

Highlights in methodology of developing the assessment framework.

Box 1. On the sideline of the summit in developing the national palltive strategic plan, we have a chance to contact with the most often palliative care experts in around of the country. The total 25 experts were in following categories by discipline:

- Expert palliativisit(3);

- Medical oncologist (adult and pediatric) expert in palliative care (4);

- Radiation oncologist concentrates on palliative care (3;)

- Anesthesiologist and pain management (2);

- Physical therapist (1);

- Pharmacotherapist (1);

- Psychiatrics and psychologist (3);

- Medical ethics (1);

- Nutritionist (1);

- Nursing (4);

- Social worker (2);

For the experts, we designed a draft explaining the logic of the research and also the inventory of the lprocess indicators considered appropriate for the FARS HPCU by reviewing the lierature, best practices and also trend analysis.

Table 1.

Process classification framework of the FARS-HPCU (core processes)

Table 2.

Process classification framework of the FARS-HPCU (support processes)

The items were scored with Likert-type scale in nine levels.[17] Score 1–2 were considered as poor, scores 3–4 as weak, score 5 as medium, scores 6–7 as good, and scores 8–9 were considered as excellent. The average of the obtained scores has been considered.

RESULTS

The main outcome indicators of the HPCU we achieved through the above mentioned methods are:

The patients benefit from the counseling services

Only patients in actual need are admitted in the HPCU

The quality and speed of services provided in the HPCU

The care patients receive is provided according to their actual need rather than the medical diagnosis

Appropriate physical and psychological conditions of HPCU space

Making sure that after receiving the required care, patients are transferred back to their previous level of care services

Making sure that referred patients to the previous level of care, can still benefit from the HPCU counseling services

Making sure those patients in the end stages of disease are promptly identified and provided with the required services.

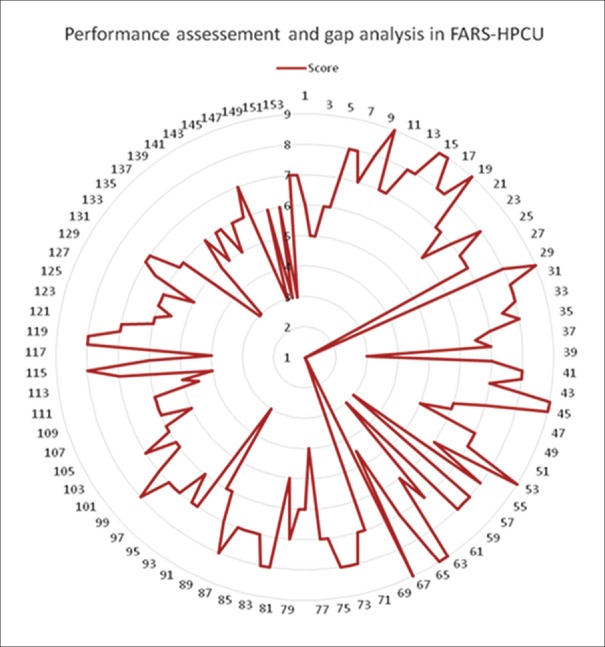

The value chain diagram has been drawn to show the main core and support processes of the FARS-HPCU [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Value Chain in FARS-HPCU-Porter diagram with main care and support processes

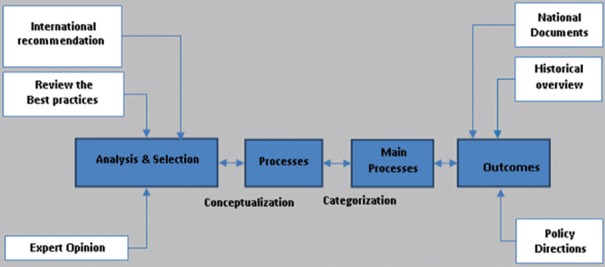

All main processes and their elements have been shown in Tables 1 and 2 in a classification framework. Mean scores were provided for the overall status of the processes indicators. After scale ranking of the processes by the different stakeholders, we have drawn a radar diagram to show an overview of the FARS-HPCU status [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

A radar diagram presents the assessment and gap of the FARS-HPCU

It is presumed that in such assessments the participating stakeholders are less likely to overestimate or underestimate the current situation and are anticipated to answer realistically. In this study, scores of ≤5 are considered as gap area [Table 3].

Table 3.

Gap area in the processes (core and support) of the FARS-HPCU

Finally, there were 25 subprocesses in the core and support processes equal or less than 5 score, which suggested the gap areas. In these areas; nine zones are in medium, 13 zones in weak, and nine zones in poor status. Figure 3 shows the gap between the current situation (as is) and the optimal situation (to be) of the HPCU-FARS at a glance and based on the conceptual framework.

DISCUSSION

In an overview, the current situation in core processes is more favorable than that in support processes. Thus, it is logically expected that the effectiveness (doing the right thing) in this unit to be in a better status than the efficiency (do things right). This issue can lead to dissatisfaction of the staff and even patients in long-term.

Core processes

A glance at the six main core processes in the model (value chain) offered for this HPCU reveals a relatively optimal balance in supporting the comprehensive care services approach. This approach is considered by the modern health and PC services. For instance, The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) profiled an award-winning PC program in the United States which integrates PC in to healthcare with specialized professionals offering comprehensive PC setting. This program led to 50% reduction in reported patient symptoms, reduction in care costs, and improved family satisfaction.[18]

Both through inpatient and outpatient PC setting, counseling processes should be considered for patients, families, and caregivers. Also providing education (including a family conference initiative, a partnership with an academic health center, internal conferences, and leadership conferences for other medical centers), family support (including symptom management for caregivers, especially free phone counseling services through limited hours daily by the palliativist and the nurses, children's programs, and bereavement information) should be considered in the best practice dissemination and community outreach.

In the other core processes, gap areas have become evident. The most important example in this regard is” planning comprehensive social care“, “bereavement support and chaplaincy services” and “post-bereavement services“.

Developing a comprehensive social care plan that addresses the social, practical, and legal needs of the patients and caregivers, including but not limited to relationships, communication, existing social and cultural networks, decision making, work and school settings, finances, sexuality/intimacy, caregiver availability/stress, and access to medicines and equipment is one of the standards of quality improvement of the inpatient PC unit.[19]

Bereavement services which were included in the PC services by the WHO in the past decade have been considered as the major component of PC.[20] Post-bereavement services are not included in HPCU, but this type of care has been considered among the standards of the high quality and modern centers.[21]

Another weakness of this system was in choosing surrogate decision makers in accordance with the State law.[22] Religious rules also play a role in determining the decision makers.[23] Cultural norms influence the decision maker and the decision as well.[15] An important point in this respect is adhering to legal instructions in terms of documentation of the conditions and decision-making about the patient.

Whereas the development of supportive and PC services for cancer patients depends on integration and interdisciplinary care,[24] one of the most important gap areas appeared to be the adequate success in providing interdisciplinary care. Making integrated approach have the added advantage of coordinating treatment protocols, implementing common clinical pathways, and improving communication between specialists; especially in the outpatient setting.[25] Meanwhile the introduction of PC services at the time of diagnosis of cancer leads to meaningful improvement in the experiences of patients and family caregivers by emphasizing symptom management, quality of life, and treatment planning.[26]

Support processes

Regarding the 10 main support processes of FARS-HPCU, except for human resources management and information management, others have possessed a relatively good status. Although, policy making and governance has revealed a relative weakness in documented policy guidance for referral and continuity care. If the interdisciplinary approaches in PC is a necessary component, policies for prioritizing and responding to referrals in a timely manner should be documented. As mentioned above, the integrative approach is the most important gap area in the core processes.

Performance management was also in a relatively good status. It may be better to assess the quality management indices separately. A complex of quality of care assessment indices such as PEACE should be used for this purpose.[27]

In the risk management domain, only the crisis management has a relative weakness. In financial management of the HPCU, the lack of control on payroll may actually affect the staffs’ motivations.

The unit has an acceptable function in cooperation with charity donors. This is an important requirement because without the financial support of the NGOs and charitable people, these units generally have very low budgets and income.

Knowledge management, determination of the required knowledge, providing and managing it, and also its implementation are also in a favorable condition in this unit. In terms of drug management, especially opioids; distribution and allocation of these drugs to those eligible for taking them is supervised by the national system in charge of distribution management of these drugs in the country. However, the control over the illegal export of these drugs in any way from this cycle needs to be further improved. The status of this unit in terms of use and maintenance of equipment has been relatively improved. By the way, providing the opioids is free of charge or at very low price for patients based on the defined national regulation.

One big obstacle of our HPCU is the management of human resources. Recruitment of personnel including physicians and nurses is not adequately supervised and strategies to attract and maintain volunteers still need to be improved. But, development, education, and maintenance of human resources are currently in a relatively good condition.

Volunteers participating in supportive and PC services in developed countries receive trainings different from those received by the personnel and a considerable amount of budget has to be allocated for this purpose.[28] Instructions for different coping mechanisms to volunteers for confronting work situations and tolerating these conditions are also important and needed to be delivered for a period of time (at least for 1 year in order for the instructions to be cost-effective).[29]

Management of data sources is another challenging point of HPCU. The information management system in core processes of the HPCU which enables the workflow is essential and electronic records can improve the interdisciplinary activities. Although production of these systems can be costly and that may be the reason for underdevelopment of such services in this unit, the open source solutions provided for this purpose can be used with a little naturalization.[30]

Considering that ethical and legal aspects of care are one of the core components in the comprehensive PC, the management of the ethical and legal issues such as the counsels, disputes, and litigations should be addressed.

CONCLUSION

The conceptual framework for assessment of the HPCU in Iran, specifically in case of FARS, including the outcome indicators, value chain, and PIs; developed and assessed through this study has shown the gap areas of the HPCU clearly.

According to the assessment, comprehensive and integrative PC should be enhanced by developing the interdisciplinary and collaborative (integrative) approach in FARS-HPCU.

To improve the integrative approach, the interdisciplinary team should communicate regularly to plan, review, and evaluate the care plan, with input from both the patient and family. The team should meet regularly to discuss provision of quality care, including staffing, policies, and clinical practices. The team leadership should have appropriate training, qualifications, and experience. Clinical multidisciplinary policy guidelines should be documented. For comprehensive approach in PC, FARS-HPCU should emphasize more on social and spiritual PC as physical aspects of care.

For development of the two mentioned approaches, improving the level of care and services and eliminating the imbalance between development of the main and support processes, the need for financial support is clear. The required budget may be provided by the financial resources allocated by the government, received fees for services, or financial help from NGOs and charities. In order to obtain the government budget, policy makers and the authorities should be informed about the importance and benefits of this unit. In order to do so, the clinical and financial outcomes of such units in the cancer center should be assessed. Such evaluations must be done in the first few years following the establishment of such units.[31]

In addition to comprehensiveness, other shortcomings of the main processes of FARS-HPCU should be resolved. For this purpose; support processes, especially human resources management and information management, should be improved. Priority should be given to recruitment of human resources, motivating them, and paying them based on their performance.

Proper strategies should be adapted to benefit from efficient and continuous help of volunteers. Development of an efficient infrastructure for information management, especially information technology, should be more emphasized starting with low-cost solutions at the beginning of the road. Management of legal and ethical affairs is another gap area that needs to be improved. Skillful consulting managers can help in this respect. In conclusion, we may state that FARS-HPCU is half-way on its development path and this study can help in designing a strategic plan for this purpose. By further assessment of gap areas and determination of priorities, this unit can become a successful model for other centers in the country.

Footnotes

Source of Support: No.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Palliative Care, Cancer Control: Knowledge into action; WHO guide for Effective Programs. World Health Organization. 2007. [Last cited on 2013 Sep 12]. Available from: http://www.who.int/cancer/publications/cancer_control_palliative/en/

- 2.Doyle D. 2nd ed. Houston: IAHPC Press; 2009. Getting Started: Guidelines and Suggestions for those Starting a Hospice/Palliative Care Service, International Association for hospice and Palliative care; p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hockley J. Role of the hospital support team. Br J Hosp Med. 1992;48:250–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Victorian Government Department of Health, Department of Health. Strengthening Palliative care: Policy and Strategic Directions 2011-2015. 2011. [Last cited on 2013 Dec 12]. Available from: www.health.vic.gov.au/palliativecare .

- 5.Dahlin C. 2nd Ed. Pittsburgh: National Consensus Project For Quality Palliative Care; 2009. [Last accessed on: 2013 Sep 02]. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. Available from: http://www.nationalconsensusproject.org/guideline . [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hui D, Elsayem A, De la Cruz M, Berger A, Zhukovsky DS, Pall S, et al. Availability and integration of palliative care at US cancer centers. JAMA. 2010;303:1054–61. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kulkarni PD. Hospital-based Palliative care: A case for integrating care with cure. Indian J Palliat Care. 2011;17:S74–6. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.76248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Porter ME. A strategy for health care reform – toward a value-based system. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:109–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0904131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance. Policy statement on defining palliative care. July 2011. [Last cited on 2013 Sep 11]. Available from: http://www.thewpca.org .

- 11.Bingely A, Clark D. Palliative Care Development in the Regional Represented by the Middle East Cancer Consortium: A Review and Comparative Analysis. National Cancer Institute. 2008. [Last cited on 2013 Oct 13]. Available from: www.mecc.cancer.gov/PCMONOGRAPH.pdf .

- 12.African Palliative Care Association, APCA Standards for Providing Quality Palliative Care across Africa. 1st ed. 2010. [Last cited on 2013 Nov 02]. Available from: www.thewpca.org .

- 13.Center to Advance Palliative Care; Policies and Tools for Hospital Palliative Care Programs, A Crosswalk of National Quality Forum Preferred Practices. 2007. [Last cited on 2013 Oct 24]. Available from: www.capc.org .

- 14.National Quality Forum, A National Framework and Preferred Practices for Palliative and Hospice Care Quality. 2006. [Last cited on 2013 Nov 11]. Available from: www.qualityforum.org .

- 15.Bullock K. The influence of culture on end-of-life decision making. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2011;7:83–98. doi: 10.1080/15524256.2011.548048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gholami AJ. Iran, Tehran: Ministry of Health and Medical Education; Accreditation Canter for Care; 2010 (In Farsi); Hospital Accreditation Standards in Iran. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elaine A, Seaman C. Likert Scales and Data Analyses. Quality Progress. 2007:64–5. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glazer A, Srinivasan V, Paprica A. A Rapid Literature Review on Integrated Palliative Home Care. Prepared by the Planning Unit Health System Planning and Research Branch Health System Strategy Division Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; April. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrell B, Paice J, Koczywas M. New standards and implications for improving the quality of supportive oncology practice. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3824–31. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.7552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. World Health Research; National cancer control programmes: Policies and managerial guidelines. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holtslander LF. Caring for bereaved family caregivers: Analyzing the context of care. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12:501–6. doi: 10.1188/08.CJON.501-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silveira MJ, Kim SY, Langa KM. Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1211–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0907901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eskew S, Meyers C. Religious belief and surrogate medical decision making. J Clin Ethics. 2009;20:192–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 3rd ed. 2007. [Last cited on 2013 Sep 02]. Available from: Nationalconsensusproject.org .

- 25.Barbour L, Cohen S, Jackson V, Kvale E, Lurse C, Nguyen D. New York, NY: Center to Advance Palliative Cancer Care; 2012. [Last cited on 2013 Sep 02]. Models for Palliative Care outside the Hospital Setting: A Technical Assistance Monograph from IPAL-OP Project. Available from: ipal.capc.org/downloads/overview-of-outpatient-palliative-care-models.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greer J, Jackson VA, Meier DE, Temel JS. Early integration of palliative care services with standard oncology care for patients with advanced cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:349–62. doi: 10.3322/caac.21192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schenck AP, Rokoske FS, Durham DD, Cagle JG, Hanson LC. The PEACE Project: Identification of quality measures for hospice and palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:1415–59. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wittenberg-Lyles E, Schneider G, Oliver DP. Results from the national hospice volunteer training survey. J Palliat Med. 2010;13:261–5. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown MV. How they cope: A qualitative study of the coping skills of hospice volunteers. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2011;28:398–402. doi: 10.1177/1049909110393946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shah KG, Slough TL, Yeh PT, Gombwa S, Kiromera A, Oden ZM, et al. Novel open-source electronic medical records system for palliative care in low-resource settings. BMC Palliat Care. 2013;12:31. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-12-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elsayem A, Swintm K, Fisch MJ, Palmer JL, Reddy S, Walker P, et al. Palliative care inpatient service in a comprehensive cancer center: Clinical and financial outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2008–14. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]