Abstract

LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) contributes to coronary heart disease. Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) increases LDL-C by inhibiting LDL-C clearance. The therapeutic potential for PCSK9 inhibitors is highlighted by the fact that PCSK9 loss-of-function carriers exhibit 15–30% lower circulating LDL-C and a disproportionately lower risk (47–88%) of experiencing a cardiovascular event. Here, we utilized pcsk9−/− mice and an anti-PCSK9 antibody to study the role of the LDL receptor (LDLR) and ApoE in PCSK9-mediated regulation of plasma cholesterol and atherosclerotic lesion development. We found that circulating cholesterol and atherosclerotic lesions were minimally modified in pcsk9−/− mice on either an LDLR- or ApoE-deficient background. Acute administration of an anti-PCSK9 antibody did not reduce circulating cholesterol in an ApoE-deficient background, but did reduce circulating cholesterol (−45%) and TGs (−36%) in APOE*3Leiden.cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) mice, which contain mouse ApoE, human mutant APOE3*Leiden, and a functional LDLR. Chronic anti-PCSK9 antibody treatment in APOE*3Leiden.CETP mice resulted in a significant reduction in atherosclerotic lesion area (−91%) and reduced lesion complexity. Taken together, these results indicate that both LDLR and ApoE are required for PCSK9 inhibitor-mediated reductions in atherosclerosis, as both are needed to increase hepatic LDLR expression.

Keywords: apolipoprotein E, anti-proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 antibody, low density lipoprotein receptor, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9

High levels of circulating LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) play a key role in the initiation and development of atherosclerosis. This contributes to the development of CVD and places patients at increased risk of experiencing an adverse cardiovascular event (1, 2).

Circulating LDL-C levels are dictated by the balance between dietary cholesterol absorption, hepatic cholesterol synthesis, storage, and clearance from the blood stream (3, 4). The LDL receptor (LDLR) plays a critical role in regulating the clearance of LDL-C (5–9). It has been shown that proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) promotes LDLR degradation, thereby reducing the number of LDLRs available to sequester LDL-C from circulation (10–16). PCSK9 is a member of the subtilisin family of serine proteases and is expressed primarily by the liver where it is secreted into circulation (17). Self-cleavage by PCSK9 enables secretion from hepatocytes and subsequent binding to the LDLR at the liver cell surface (13, 16, 18, 19). The LDLR:PCSK9 complex enters the cell and is transported to the lysosome compartment and degraded. This leads to a reduction in hepatic LDLR levels (12). Thus, higher circulating PCSK9 levels increase circulating LDL-C by preventing LDLR-mediated LDL-C clearance, whereas lower circulating PCSK9 levels decrease circulating LDL-C by increasing LDLR-mediated LDL-C clearance. The impact of PCSK9-mediated regulation of LDL-C is evident in studies of individuals with gain-of-function PCSK9 mutations. These individuals possess higher circulating LDL-C and an increased risk of experiencing a cardiovascular event (20–22). Additionally, PCSK9 loss-of-function carriers have 15–30% lower circulating LDL-C and a disproportionately lower risk (47–88%) of experiencing a cardiovascular event (23). This disproportionate reduction in risk is in contrast to statins, where 5 year treatment reduced cardiovascular events by 40% even when LDL-C was reduced to 80 mg/dl (24). Whether this disproportionate reduction in risk is due to PCSK9 having a direct negative effect at the atherosclerotic lesion or if the additional benefit is driven by a modest lifelong reduction in serum cholesterol is unclear. These observations have led to the development of PCSK9 inhibitors as a means to therapeutically reduce LDL-C and the associated CVD risk (25–29). Inhibition of PCSK9 by monoclonal antibodies, adnectins, or siRNAs reduces LDL-C levels in patients, and clinical trials designed to assess the effect of anti-PCSK9 therapies on cardiovascular outcomes are underway (30–42).

ApoE, like ApoB, is present in lipoproteins and functions as a ligand of the LDLR and is important for the clearance of TG-rich lipoproteins. The decrease in HDL cholesterol (HDL-C) in pcsk9−/− mice has been attributed to the binding of ApoE containing HDL to the upregulated LDLR (11). Even with a functional LDLR and ApoB, mutations in APOE in humans can lead to hypercholesterolemia (43–46). To date the role of ApoE in the lipid lowering and athero-protective effects of PCSK9 inhibition is unclear. PCSK9 overexpression in an apoe-deficient background has been reported to be proatherogenic, while PCSK9 deletion in apoe-deficient mice leads to a reduction in the amount of cholesterol ester found within the aorta, even though the plaque size and total plasma cholesterol levels remain unchanged (47). The contribution of cholesterol ester content to atherosclerotic lesion development in the absence of changes in lesion area are unknown, but these data hint that a functional ApoE-LDLR pathway is essential for PCSK9-mediated changes in atherosclerosis that are driven by decreases in plasma cholesterol. To investigate this, we utilized both genetically engineered knockout mice (pcsk9−/−) and an anti-PCSK9 antibody to examine the effect of PCSK9 inhibition on plasma lipoproteins and atherosclerotic lesion development in mice lacking the LDLR or ApoE, as well as in APOE*3Leiden.cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) mice (47), which have mouse ApoE and LDLR but hampered clearance of the ApoB-containing lipoproteins due to the expression of human mutant APOE*3Leiden (48). The APOE*3Leiden.CETP mice are a well-established mouse model for familial dysbetalipoproteinemia with human-like lipoprotein metabolism and atherosclerosis development, which respond in a human-like manner to both lipid lowering as well as HDL-raising drugs (like statins, fibrates, niacin, etc.) used in the treatment of CVD (49–52).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibody generation and purification

The fully human PCSK9-targeting antibody, mAb1, was generated as described previously (25). Briefly, mice engineered to express human IgG antibodies were immunized with human PCSK9. Determination of binding affinity, screening for cross reactivity to mouse PCSK9, and activity in a cell-based LDL uptake assay led to mAb1 selection.

cDNA sequences encoding the variable domains of heavy and light chains of mAb1 were fused to constant domains of mouse IgG1 heavy chain and mouse lambda light chain. The resulting cDNA sequences encoding the chimeric mAb1 (CmAb1) heavy chains and light chains were inserted into pTT5 expression plasmid separately. CmAb1 mouse IgG1 was expressed by cotransfecting 293 6E cells with pTT5 plasmids containing light chain and heavy chain sequences. Expressed chimeric antibody was purified by capturing on a MabSelect SuRe column and polished on a SP-Sepharose column as previously described (25).

Binding of mAb1 and CmAb1 to mouse PCSK9 was measured in a kinetic binding assay by BIAcore. Mouse anti-His antibody (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) was immobilized on all four flow cells of a CM5 chip using amine coupling reagents (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) with an approximate density of 5,000–6,000 RU. His-tagged PCSK9 was captured on the second and fourth flow cells at an approximate density of 130 RU for mouse PCSK9. Flow cells one and three were used as background controls. Anti-PCSK9 antibody at 100 nM was diluted in PBS plus 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 0.005% P20, and injected over the captured PCSK9 surface with a 50 ul/min flow rate (5 min association and 5 min dissociation). CmAb1 showed very similar binding activity compared with mAb1 (25).

Control mouse IgG1 was raised against a PeptiBody peptide AGP-3. The resulting antibody was produced in stably transfected Chinese hamster ovary cells and purified using the same method as CmAb1.

In vivo

All animal care and experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Amgen for work performed at Amgen and by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Netherlands Organization for Applied Research for work performed at TNO Metabolic Health Research. All mice were housed and maintained under standard environmental conditions with a 12 h light-dark cycle and had free access to food and water. All mice were in a C57Bl/6 background.

Ldlr−/− and apoE−/− mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories. Each strain was crossed with pcsk9−/− mice (Ozgene Pty Ltd, Bentley, Australia) to generate ldlr+/−/pcsk9+/− and apoe+/−/pcsk9+/− colonies. These pcsk9+/− colonies were crossed again to generate the male double knockouts (ldlr−/−/pcsk9−/− and apoe−/−/pcsk9−/−) and the respective littermate controls (ldlr−/−/pcsk9+/+ and apoe−/−/pcsk9+/+) used for these experiments. Mice (male) on the ldlr−/− background were fed an atherogenic diet (Research Diets D12108C) containing 40% kcal from fat and 1.25% cholesterol. Mice (male) on the apoe−/− background were fed chow diet (Harlan 2020X).

Female APOE*3Leiden.CETP transgenic mice (11–13 weeks of age) (53), expressing human CETP under control of its natural flanking regions, were used. APOE*3Leiden.CETP transgenic mice were fed a semi-synthetic cholesterol-rich diet containing 15% (w/w) cacao butter and 0.15% cholesterol [Western-type diet (WTD); Hope Farms, Woerden, The Netherlands] for a run-in period of 3–4 weeks to increase plasma total cholesterol (TC) levels to approximately 650 mg/dl. Mice were matched based on body weight, TC, TGs, and age.

In pharmacologic inhibitory studies, antibodies were administered by sc injection (10 mg/kg) every 10 days for 14 weeks, to examine effects on atherosclerotic plaque development.

Whole blood was collected by tail nick, vena cava, or cardiac puncture. At study termination, animals were euthanized either by CO2 asphyxiation or by exsanguination under anesthesia (100 mg/kg ketamine, 5 mg/kg diazepam).

For liver collection, sections of the right medial or left lobe were excised, flash frozen, and stored until further use. For heart and aorta isolation, hearts were either isolated and placed directly in formalin or animals were perfused by gravity flow under anesthesia. Perfusion was performed by inserting a 25 gauge needle into the apex of the left ventricle and nicking the right atrium. Animals were perfused with saline for 10 min followed by 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min for fixation. Hearts and aortas were removed, immersed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and stored at 4°C.

Cholesterol, TG analysis, PCSK9 ELISA

Mouse serum or EDTA plasma was obtained from whole blood collected via centrifugation. Serum or plasma cholesterol and TGs were analyzed using either a Cobas Integra 400 chemistry analyzer or enzymatic kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions (catalog numbers 1458216 and 1488872, respectively; Roche/Hitachi). In some instances, pooled serum from mice treated with either control or anti-PCSK9 monoclonal antibodies was fractionated by fast protein liquid chromatography (Superose 6 10/300 GL column). Cholesterol content of each fraction was measured using the HDL-C E kit omitting the phosphotungstate-magnesium salt precipitation step (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan). Mouse PCSK9 serum protein levels were measured by sandwich ELISA (R&D Systems; MPC900) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Hepatic LDLR mRNA and protein expression

Total RNA was extracted from liver tissue samples using RNA-Bee (Amsbio, Oxon, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Random primers were used to convert RNA to single stranded cDNA by reverse transcription (Promega, Fitchburg, WI) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Levels of cDNA were measured by real-time PCR using the 7500 Fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Assay-on-demand primers and probes were obtained from Applied Biosystems. The mRNA levels were normalized to mRNA levels of three housekeeping genes (i.e., cyclophilin, HPRT, and GAPDH). The level of mRNA expression for each gene of interest was calculated according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Applied Biosystems).

For protein expression, liver tissues were homogenized in lysis buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) containing complete protease inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics) and incubated on ice for 30 min. The lysis buffer consisted of 50 mM Tris-HCL (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 0.25% deoxycholic acid, 1% NP-40 (Igepal), 1 mM EDTA, protease inhibitor cocktail (complete, Roche), 1 mM PMSF, and 1 mM Na3VO4. Samples were then centrifuged at 13,000 g at 4°C for 20 min. Protein concentration in cell lysates was determined by BioRad protein assay reagents (BioRad) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Fifty micrograms of protein lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (BioRad). Blots were subjected to goat anti-mouse LDLR from R&D Systems and rabbit anti-goat HRP from Santa Cruz. Mouse anti-α-actin from Cell Signaling Technologies was used to confirm equal loading in conjunction with horse anti-mouse HRP from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Blots were developed with Bio-Rad Clarity Western ECL (BioRad) and subjected to ChemiDoc™ XRS+ imaging system. Intensities of protein bands were quantified using Image Lab™ software.

Atherosclerosis measurements

Hearts embedded in paraffin were cross-sectioned (5 μm each) through the entire aortic root area. Sections were stained with either Verhoeff-Van Gieson (VVG) or hematoxylin-phloxine-saffron to measure lesion area. In some studies, histological analysis was performed by Charles River Discovery Research Services and sections were stained with Mac-2 to monitor macrophage content. For each mouse, three or four sections at intervals of 40 to 50 μm were used for quantitative and qualitative assessment of the atherosclerotic lesions (54, 55). To qualify lesion severity, the lesions were classified into one of five categories according to the American Heart Association classification: early fatty streak (I), regular fatty streak (II), mild plaque (III), moderate plaque (IV), and severe plaque (V), as previously described (56). To assess lesion severity as a percentage of all lesions, type I through III lesions were classified as mild lesions and type IV and V lesions were classified as severe lesions. Images were acquired with an Olympus BX51 microscope. Atherosclerosis development was quantified by measuring lesion areas using Cell D imaging software (Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions).

For en face analysis, aortas were soaked in PBS followed by 70% ethanol (5 min each). Aortas were subsequently soaked with Sudan IV stain for 6 min with occasional agitation. Aortas were then rinsed twice with 80% ethanol followed by PBS (3 min each). Aortas were mounted and photographed under a stereo microscope. Aortic plaque area was quantified by Image-Pro.

Statistical analysis

Significance between groups was calculated by two-way ANOVA, Sidak posttest, for longitudinal studies, by a two-tailed t-test for single end points containing two groups, and by a one-way ANOVA, Tukey posttest, using Prism (GraphPad, Inc). In the figures: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001.

RESULTS

LDLR is the predominant means for PCSK9-mediated regulation of circulating cholesterol and is required for PCSK9 inhibitor-mediated regulation of atherosclerosis

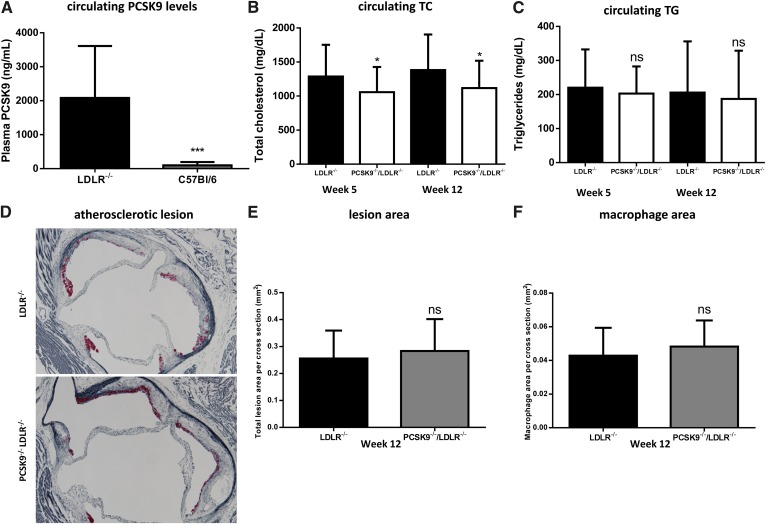

To investigate whether LDLR influences circulating PCSK9 levels, we measured plasma PCSK9 levels in ldlr−/− and WT mice and found a significant elevation in plasma PCSK9 in ldlr−/− mice (2,083 ± 1,529 ng/ml and 98 ± 98 ng/ml) providing further confirmation that PCSK9 and LDLR influence the clearance of one another (Fig. 1A) (57, 58).

Fig. 1.

Minimal effect of deleting PCSK9 on circulating lipids or atherosclerosis in LDLR-deficient mice. A: Plasma PCSK9 levels are higher in ldlr−/− mice compared with C57Bl/6 mice, consistent with the LDLR being a key clearance mechanism for PCSK9 (n = 9, ldlr−/−; n = 12, C57Bl/6). The pcsk9−/−/ldlr−/− mice exhibit a slight decrease in TC (B) but not TGs (C) relative to ldlr−/− mice when fed a WTD (n = 41, ldlr−/−; n = 43, pcsk9−/−/ldlr−/−). D: The aortic sinus was sectioned and stained with VVG to measure lesion area (blue) and Mac-2 to monitor macrophage content (red). D–F: No difference in atherosclerosis development or macrophage accumulation was observed in the aortic sinus for ldlr−/− mice relative to pcsk9−/−/ldlr−/− mice (n = 25 per group). Data represented as the means (bars) ± SD (*P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, as compared with ldlr−/−, two-tailed t-test, unpaired).

Pcsk9−/− mice exhibit increased hepatic LDLR levels leading to lower circulating cholesterol levels (26). However, it is unclear if PCSK9 also influences the levels of circulating cholesterol independent of the LDLR (47). We investigated this possibility by comparing the levels of circulating cholesterol in 12-week-old ldlr−/−/pcsk9−/− mice relative to ldlr−/− littermate controls. Mice were fed a WTD (40% kcal from fat and 1.25% cholesterol) for 12 weeks, and circulating cholesterol and TG levels were measured at 5 and 12 weeks from the initiation of WTD feeding. The ldlr−/−/pcsk9−/− mice exhibited a slight but significant (18–19%) decrease in both TC and LDL-C at 5 and 12 weeks and a decrease in HDL-C at 12 weeks (Fig. 1B, supplementary Fig. I) while circulating TG levels were not significantly different between groups at either time point (Fig. 1C). To determine whether these reductions in TC levels translated into reduced atherosclerosis development, we measured the amount of atherosclerotic plaque within the aorta and the aortic root after 12 weeks. Atherosclerotic lesions covered 11 ± 5% and 10 ± 3% of the aortic area in the ldlr−/− and ldlr−/−/pcsk9−/− mice, respectively (supplementary Fig. II). Similarly, no significant difference was observed in lesion area (0.26 ± 0.10 mm2 and 0.28 ± 0.11 mm2) or macrophage content (0.04 ± 0.02 mm2 and 0.05 ± 0.02 mm2) in the aortic sinus of ldlr−/− and ldlr−/−/pcsk9−/− mice, respectively (Fig. 1D–F). Thus, deletion of PCSK9 in the absence of the LDLR reduces circulating cholesterol levels, suggesting that other receptors or mechanisms are involved in the PCSK9-mediated cholesterol clearance.

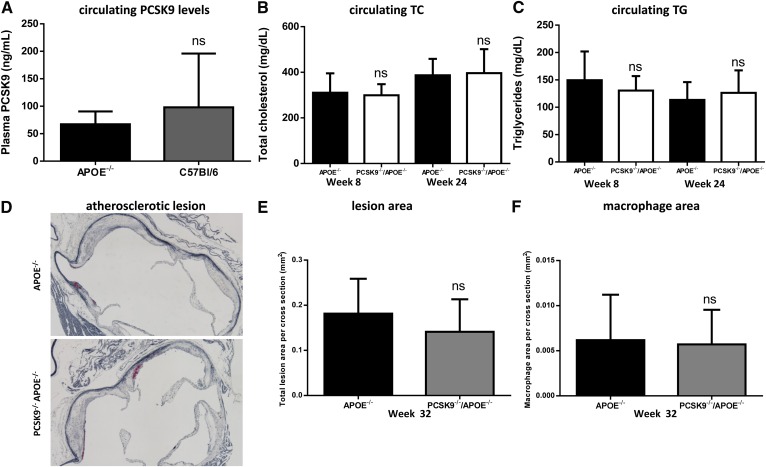

PCSK9 deletion in apoe−/− mice does not affect circulating cholesterol and atherosclerosis

Another key player and essential protein for normal particle uptake by the liver via the LDLR gene family is ApoE, which is present on chylomicrons, VLDLs, IDLs, and LDLs, and also on large HDL particles. Consequently, apoe−/− mice exhibit elevated circulating cholesterol levels leading to accelerated atherosclerotic plaque accumulation on a chow diet (59, 60). In contrast to ldlr−/− mice, apoe−/− mice exhibit comparable PCSK9 plasma and hepatic LDLR protein levels relative to WT mice (67 ± 23 ng/ml and 98 ± 98 ng/ml, respectively; Fig. 2A, supplementary Fig. III). Comparing apoe−/−/pcsk9−/− and apoe−/− littermate controls revealed that there was no difference in circulating TC, HDLs, LDLs, or TGs, and there was no significant difference in hepatic LDLR protein levels (Fig. 2B, C; supplementary Figs. IV, V). In addition, there was no difference in either atherosclerotic plaque accumulation (0.18 ± 0.08 mm2 and 0.14 ± 0.07 mm2) or macrophage content (0.006 ± 0.005 mm2 and 0.006 ± 0.003 mm2) within the aortic root between apoe−/−/pcsk9−/− and apoe−/− littermate controls at 32 weeks of age, respectively (Fig. 2D–F). Together these data demonstrate that in the absence of ApoE, expected lipid lowering and atheroprotective effects caused by the deletion of PCSK9 are not apparent.

Fig. 2.

No effect of deleting PCSK9 on circulating lipids or atherosclerosis in APOE-deficient mice. A: Comparable levels of PCSK9 are observed in apoe−/− mice compared with C57Bl/6 mice (n = 12, apoe−/−; n = 12, C57Bl/6). No significant reduction in circulating TC (B) and TG (C) levels was observed in pcsk9−/−/apoe−/− mice relative to apoe−/− mice (n = 9 (8 weeks), n = 21 (24 weeks) for pcsk9−/−/apoe−/−; n = 11 (8 weeks), n = 15 (24 weeks) for apoe−/−). D–F: The aortic sinus was sectioned and stained with VVG to measure lesion area (blue) and Mac-2 to monitor macrophage content (red), and consistent with these observations, no difference in atherosclerosis development or macrophage accumulation was observed in the aortic sinus for apoe−/− mice relative to pcsk9−/−/apoe−/− mice (n = 18, pcsk9−/−/apoe−/−; n = 20, apoe−/−). Data represented as the means (bars) ± SD, two-tailed t-test, unpaired, as compared with apoe−/−.

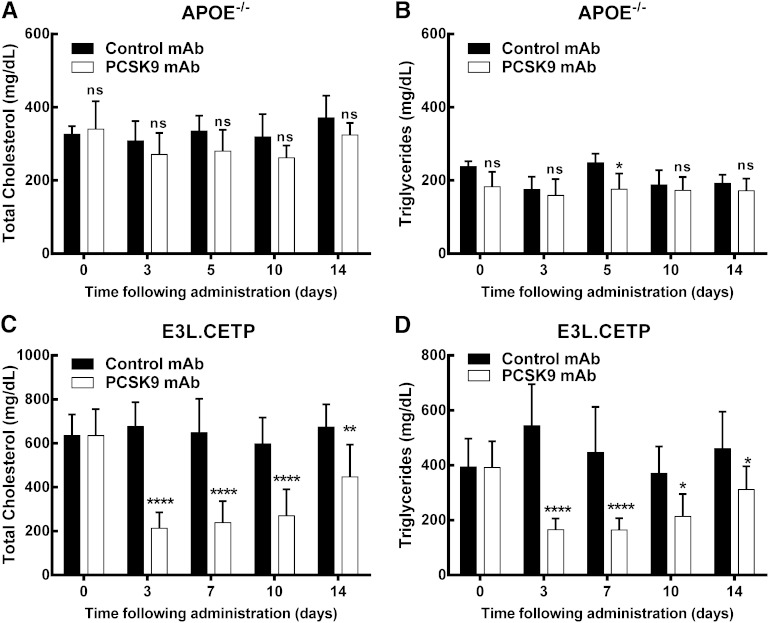

PCSK9 inhibition is effective in APOE*3Leiden.CETP mice but not in apoe−/− mice

Recently, several PCSK9 monoclonal antibodies have been developed as a therapy to reduce plasma lipids. To determine whether anti-PCSK9 antibody treatment can lower circulating lipids in the absence of ApoE, we administered a single dose (10 mg/kg, sc) of either an anti-PCSK9 antibody (CmAb1) or control antibody to either apoe−/− or APOE*3Leiden.CETP mice, which express both mouse ApoE and the human mutant APOE3*Leiden, as well as a functional LDLR.

Consistent with our observations utilizing pcsk9−/− mice, a single dose of anti-PCSK9 antibody did not significantly lower circulating cholesterol levels at up to 14 days posttreatment or affect hepatic LDLR protein levels in apoe−/− mice (Fig. 3A, supplementary Fig. VI). This is in contrast to C57Bl/6 mice, where a significant increase in hepatic LDLR was observed following anti-PCSK9 antibody treatment (supplementary Fig. VII), which is consistent with our previous findings for PCSK9 inhibition in WT mice (25). Circulating TGs were not significantly different at day 3, 10, or 14, but did reach significance at the day 5 time point (P < 0.05, Fig. 3B). Additionally, chronic administration of anti-PCSK9 antibody (10 mg/kg, sc, every 10 days) failed to reduce circulating lipid levels or atherosclerosis in apoe−/− mice (supplementary Fig. VIII). Together, these data suggest that ApoE is required for cholesterol and TG lowering, and atherosclerosis reduction, by anti-PCSK9 antibody.

Fig. 3.

Anti-PCSK9 antibody treatment reduces TC and TG levels in APOE*3Leiden.CETP mice but not apoe−/− mice. No significant reduction in TC (A) and only a slight but significant reduction in TGs 5 days posttreatment (B) are observed for anti-PCSK9 antibody-treated apoe−/− mice relative to control antibody-treated apoe−/− mice [10 mg/kg (sc) day 0, n = 5 per group]. This contrasts results with APOE*3Leiden.CETP mice, where anti-PCSK9 antibody treatment resulted in a significant decrease in TC (C) and TGs (D) (10 mg/kg (sc) day 0, n = 8 per group). Data represented as the means (bars) ± SD, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001, as compared with control, two-way ANOVA, Sidak posttest.

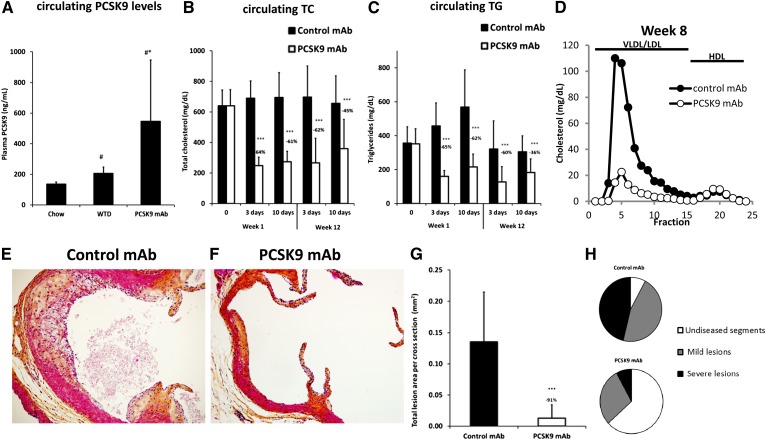

In contrast, in APOE*3Leiden.CETP mice the single dose sc injection of anti-PCSK9 antibody significantly reduced both cholesterol (up to 69%) and TGs (up to 70%) during 14 days posttreatment (Fig. 3C, D) compared with control antibody. This corresponded to a significant increase in hepatic LDLR mRNA and protein expression (supplementary Fig. IX). We next assessed the effect of anti-PCSK9 antibody (10 mg/kg, sc, every 10 days) on atherosclerosis in APOE*3Leiden.CETP mice on a WTD. As compared with a chow diet, the WTD, containing 0.15% cholesterol, increased PCSK9 levels by 51% (from 135.4 ± 14.2 ng/ml to 205.2 ± 41.9 ng/ml, P < 0.05; Fig. 4A). Treatment with anti-PCSK9 antibody further increased the circulating PCSK9 levels by another 166% (to 545.8 ± 399.7 ng/ml, P < 0.01; Fig. 4A), demonstrating circulating complexes of antibody bound to PCSK9. During the 14 week treatment, consistent and significant reductions in TC and TG levels were observed as measured 3 and 10 days after the first (week 1) and ninth (week 12) injection (Fig. 4B, C). On average, TC was reduced by 67% (P < 0.001), which was driven by a decrease in nonHDL-C (Fig. 4D), and TGs were reduced by 61% (P < 0.001), as compared with control. After 14 weeks of treatment, atherosclerosis development was reduced by 91% (P < 0.001) in the mice treated with anti-PCSK9 antibody as compared with control (Fig. 4E–G). Lesion severity was also reduced, with 8-fold more lesion-free segments in the animals treated with anti-PCSK9 antibody, as compared with control (7.8 ± 9.2% in control and 62.5 ± 31.0% in anti-PCSK9 antibody; P < 0.001), and a strong significant reduction in the percentage of severe lesions (46.2 ± 23.9% in control and 7.8 ± 15.1% in anti-PCSK9 antibody; P < 0.001; Fig. 4H). All together these data suggest that LDLR and ApoE are required for the atheroprotective effects of PCSK9 inhibition. Moreover we clearly demonstrate that an anti-PCSK9 antibody is highly efficacious in reducing lipid levels and atherosclerosis development in diet-induced hyperlipidemic APOE*3Leiden.CETP mice (a translational model for dysbetalipoproteinemia), which have an intact ApoE-LDLR clearance pathway.

Fig. 4.

Anti-PCSK9 antibody treatment reduces atherosclerosis in APOE*3Leiden.CETP mice. Plasma PCSK9 levels (A) in APOE*3Leiden.CETP mice were determined on chow diet and WTD, as well as two weeks after a single injection with anti-PSCK9 antibody (10 mg/kg, sc) in mice fed WTD. Data represented as the means (bars) ± SD (n = 8 per group). *P < 0.01 versus chow; #P < 0.05 versus WD, one-way ANOVA, Tukey posttest. To assess the effect on atherosclerosis, control or anti-PCSK9 antibody was injected sc every 10 days for 14 weeks in APOE*3Leiden.CETP mice. Plasma TC (B) and TGs (C) were measured at 3 and 10 days postinjection in the first and twelfth week of treatment. Data represented as means (bars) ± SD (n = 15 per group). ***P < 0.001 versus control antibody. D: Fast protein liquid chromatography fractionation of pooled plasma samples are shown from week 8. Atherosclerosis development was determined in the aortic sinus of APOE*3Leiden.CETP mice. E–F: Representative pictures of control antibody- and anti-PCSK9 antibody-treated mice are shown. The total lesion area per cross-section (G) was measured and lesion severity (H) was determined. Data represented as means (bars) ± SD (n = 15 per group). ***P < 0.001 versus control antibody.

DISCUSSION

Classic work, such as that by Ishibashi et al. (61), has set the foundation of understanding of ApoE and LDLR in lipoprotein homeostasis. To study the role of LDLR and ApoE on PCSK9-mediated regulation of plasma cholesterol and atherosclerosis lesion development, we utilized ldlr−/−, apoe−/−, and APOE*3Leiden.CETP mice. We demonstrate that circulating cholesterol and atherosclerotic lesions are minimally modified in pcsk9−/− mice on either an ldlr−/− or an apoe−/− background, strongly suggesting requirement of both proteins for robust atheroprotection mediated by PCSK9 inhibition. It is likely that the minor effects on plasma cholesterol lowering are the major reason for the lack of lesion reduction, as the key role of lipids in driving atherosclerotic lesion development in rodent models has been well-defined (62). We also demonstrate the ability of anti-PCSK9 monoclonal antibody to robustly reduce atherosclerosis in a mouse model with a functional ApoE-LDLR pathway, but with no effect when ApoE is absent.

We observed small but significant reductions in serum cholesterol levels after deletion of pcsk9 in ldlr−/− mice. These data are in contrast with previous studies showing no effect of pcsk9 deletion or PCSK9 inhibition by mAbs (25, 47). However, these studies used low-cholesterol diets (≤0.2% w/w cholesterol) in contrast to the current study (1.25% w/w), which might be the reason for the discrepancy in effect. The small but significant reduction in serum cholesterol levels after deletion of pcsk9 in ldlr−/− mice might relate to potential effects of PCSK9 in enabling ApoB secretion in nascent VLDL, or perhaps in upregulation of other LDLR family members, such as LDLR related protein 1 (LRP1), that could also bind and clear lipoproteins (63–68). Alternatively, Le May et al. (69) demonstrated that transintestinal cholesterol excretion (TICE) is upregulated in pcsk9−/− mice driven by increased intestinal LDLR expression. Although TICE was not examined in this study, if upregulated in pcsk9−/−/ldlr−/− mice, this could point to an unidentified LDLR-independent mechanism of TICE.

After deleting or inhibiting PCSK9 in apoe−/− mice we anticipated decreases in ApoB-containing lipoproteins (and hence some plasma cholesterol reduction) by the expected increase in liver LDLR expression, even though lipoproteins normally containing ApoE would be unaffected. However, our experiments clearly show that in absence of ApoE, PCSK9 deletion or inhibition does not reduce lipids, whereas in the presence of ApoE, using the APOE*3Leiden.CETP mice, PCSK9 inhibition is effective. Further, we show that in the absence of ApoE, PCSK9 inhibition does not lead to LDLR upregulation, which was also unexpected. Of course the lack of effect on LDLR expression after PCSK9 inhibition in apoe−/− mice most likely explains the absence of lipid lowering effects. This phenomenon, however, was not previously explained.

We hypothesize that in the absence of ApoE there is no uptake and intracellular trafficking of LDLR (bound to the lipoprotein), and consequently there is no shuttling of the LDLR into the lysosomal degradation pathway. In this situation when the LDLR is not degraded, PCSK9 inhibition, rescuing the LDLR from degradation, is not effective. Supportive data was provided by Mortimer et al. (70), showing that under normal circumstances, chylomicron remnants are rapidly internalized by the LDLR and catabolized in hepatocytes, with a critical requirement for ApoE. Ishibashi et al. (71) showed similar remnant clearance in apoe−/− mice and ldlr−/−/apoe−/− mice, strongly suggesting a minor function of the LDLR in apoe−/− mice.

In both ldlr−/− and apoe−/− strains, knockout of PCSK9 did not affect lesion formation, which is consistent with the results reported by Denis et al. (47), although the authors concluded a protection from atherosclerosis based on aortic cholesterol ester levels. They found that aortic cholesterol levels were reduced, without observing effects on lesion area in the aortic root or thoracic aorta in apoe−/−/pcsk9−/−, as compared with their respective apoe−/− controls. We did not measure aortic cholesterol ester levels in our studies.

Here we provide further evidence that ApoE is necessary for the atheroprotective effects of PCSK9 inhibition, as treating APOE*3Leiden.CETP mice with anti-PCSK9 antibodies resulted in significant and sustained reductions in TC and TG levels, which translated to reduced atherosclerosis development in the aortic root. While normal WT mice have a very rapid clearance of apoB-containing lipoproteins, APOE*3Leiden mice have an impaired clearance and increased TG levels, and are thereby mimicking the slow clearance observed in humans, particularly in patients with familial dysbetalipoproteinemia (45). Upon feeding saturated fat and cholesterol, hyperlipidemia and atherosclerosis will develop. These animals also respond in a human-like manner to drugs used in the treatment of CVD (like statins, fibrates, antihypertensives, etc.) (49, 54, 72–74). However, APOE*3Leiden mice (like WT mice) do not possess a CETP gene, and therefore these mice do not respond to HDL-modulating interventions. By cross-breeding the APOE*3Leiden mice to mice expressing the human CETP gene (75), APOE*3Leiden.CETP mice were obtained that respond to both lipid-lowering as well as HDL-raising interventions (50–53, 76). In the current study, we found significant lowering effects of anti-PCSK9 antibodies on TC and TG levels in APOE*3Leiden.CETP mice, but HDL-C was not affected (data not shown).

Other than the plasma cholesterol modulating effect, other potential atherosclerosis-related effects of PCSK9 have been described or suggested. Previously, Ferri et al. (77) reported that PCSK9 is expressed in human vessel walls and produced locally by vessel smooth muscle cells causing a local effect, and it was suggested that PCSK9 could enter the subendothelial space from the circulation either by itself or in association with LDL. In addition, it has been hypothesized that PCSK9 could impact the expression of LDLR on lesion monocytes and macrophages modulating foam cell formation and/or promoting apoptosis (78). Although our analysis was quite limited, we conclude that PCSK9-mediated local effects at the lesion, reflected by lesion area and macrophage number, is not significant in the models utilized here. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that certain biochemical changes may have occurred in the lesion due to the absence or inhibition of PCSK9.

The difficulty in examining the effect of human and humanized biologics in animal models, particularly when chronic dosing is required, is the potential appearance of neutralizing anti-drug antibodies reducing the efficacy of the therapeutic. In the study described here, there was clear evidence that after 12 weeks of treatment (9 injections) this was the case for approximately 30% of the mice, as demonstrated by a reduced efficacy in lipid lowering in those mice. Regardless, even with all study animals included in the analysis, the effect on atherosclerotic lesions was highly significant.

The ability of anti-PCSK9 therapies to lower LDL-C in human subjects is evident from numerous late stage clinical trials. The lipid lowering effect of statins has been shown to reduce the risk of cardiovascular events and death in several outcome trials (30–41, 79). Determining whether anti-PCSK9 antibody therapies will be efficacious in reducing the risk of cardiovascular events and death, as suggested by the current study using APOE*3Leiden.CETP mice, will be defined in the current outcome trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Wei Wang for measuring the binding characteristics of CmAb1 and Charles River Discovery Research Services for histological support.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- CETP

- cholesteryl ester transfer protein

- CmAb1

- chimeric mAb1

- HDL-C

- HDL cholesterol

- LDL-C

- LDL cholesterol

- LDLR

- LDL receptor

- PCSK9

- proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9

- TC

- total cholesterol

- TICE

- transintestinal cholesterol excretion

- VVG

- Verhoeff-Van Gieson

- WTD

- Western-type diet

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains supplementary data in the form of nine figures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Steinberg D. 2004. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. An interpretive history of the cholesterol controversy: part I. J. Lipid Res. 45: 1583–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinberg D. 2005. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. An interpretive history of the cholesterol controversy: part II: the early evidence linking hypercholesterolemia to coronary disease in humans. J. Lipid Res. 46: 179–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maxfield F. R., Tabas I. 2005. Role of cholesterol and lipid organization in disease. Nature. 438: 612–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gylling H. 2004. Cholesterol metabolism and its implications for therapeutic interventions in patients with hypercholesterolaemia. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 58: 859–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Top B., Koeleman B. P., Gevers Leuven J. A., Havekes L. M., Frants R. R. 1990. Rearrangements in the LDL receptor gene in Dutch familial hypercholesterolemic patients and the presence of a common 4 kb deletion. Atherosclerosis. 83: 127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hummel M., Li Z. G., Pfaffinger D., Neven L., Scanu A. M. 1990. Familial hypercholesterolemia in a rhesus monkey pedigree: molecular basis of low density lipoprotein receptor deficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 87: 3122–3126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson J. M., Johnston D. E., Jefferson D. M., Mulligan R. C. 1988. Correction of the genetic defect in hepatocytes from the Watanabe heritable hyperlipidemic rabbit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 85: 4421–4425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldstein J. L., Brown M. S. 2009. The LDL receptor. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 29: 431–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L. 2004. Lowering plasma cholesterol by raising ldl receptors. 1981. Atheroscler. Suppl. 5: 57–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maxwell K. N., Breslow J. L. 2004. Adenoviral-mediated expression of Pcsk9 in mice results in a low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout phenotype. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101: 7100–7105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rashid S., Curtis D. E., Garuti R., Anderson N. N., Bashmakov Y., Ho Y. K., Hammer R. E., Moon Y. A., Horton J. D. 2005. Decreased plasma cholesterol and hypersensitivity to statins in mice lacking Pcsk9. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102: 5374–5379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lagace T. A., Curtis D. E., Garuti R., McNutt M. C., Park S. W., Prather H. B., Anderson N. N., Ho Y. K., Hammer R. E., Horton J. D. 2006. Secreted PCSK9 decreases the number of LDL receptors in hepatocytes and in livers of parabiotic mice. J. Clin. Invest. 116: 2995–3005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwon H. J., Lagace T. A., McNutt M. C., Horton J. D., Deisenhofer J. 2008. Molecular basis for LDL receptor recognition by PCSK9. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105: 1820–1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang D. W., Lagace T. A., Garuti R., Zhao Z., McDonald M., Horton J. D., Cohen J. C., Hobbs H. H. 2007. Binding of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 to epidermal growth factor-like repeat A of low density lipoprotein receptor decreases receptor recycling and increases degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 282: 18602–18612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen M. A., Kosenko T., Lagace T. A. 2014. Internalized PCSK9 dissociates from recycling LDL receptors in PCSK9-resistant SV-589 fibroblasts. J. Lipid Res. 55: 266–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benjannet S., Rhainds D., Essalmani R., Mayne J., Wickham L., Jin W., Asselin M. C., Hamelin J., Varret M., Allard D., et al. 2004. NARC-1/PCSK9 and its natural mutants: zymogen cleavage and effects on the low density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor and LDL cholesterol. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 48865–48875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seidah N. G., Benjannet S., Wickham L., Marcinkiewicz J., Jasmin S. B., Stifani S., Basak A., Prat A., Chretien M. 2003. The secretory proprotein convertase neural apoptosis-regulated convertase 1 (NARC-1): liver regeneration and neuronal differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100: 928–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Du F., Hui Y., Zhang M., Linton M. F., Fazio S., Fan D. 2011. Novel domain interaction regulates secretion of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) protein. J. Biol. Chem. 286: 43054–43061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piper D. E., Jackson S., Liu Q., Romanow W. G., Shetterly S., Thibault S. T., Shan B., Walker N. P. 2007. The crystal structure of PCSK9: a regulator of plasma LDL-cholesterol. Structure. 15: 545–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kotowski I. K., Pertsemlidis A., Luke A., Cooper R. S., Vega G. L., Cohen J. C., Hobbs H. H. 2006. A spectrum of PCSK9 alleles contributes to plasma levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 78: 410–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abifadel M., Varret M., Rabes J. P., Allard D., Ouguerram K., Devillers M., Cruaud C., Benjannet S., Wickham L., Erlich D., et al. 2003. Mutations in PCSK9 cause autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia. Nat. Genet. 34: 154–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naoumova R. P., Tosi I., Patel D., Neuwirth C., Horswell S. D., Marais A. D., van Heyningen C., Soutar A. K. 2005. Severe hypercholesterolemia in four British families with the D374Y mutation in the PCSK9 gene: long-term follow-up and treatment response. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25: 2654–2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen J. C., Boerwinkle E., Mosley T. H., Jr, Hobbs H. H. 2006. Sequence variations in PCSK9, low LDL, and protection against coronary heart disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 354: 1264–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baigent C., Keech A., Kearney P. M., Blackwell L., Buck G., Pollicino C., Kirby A., Sourjina T., Peto R., Collins R., et al. 2005. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 366: 1267–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan J. C., Piper D. E., Cao Q., Liu D., King C., Wang W., Tang J., Liu Q., Higbee J., Xia Z., et al. 2009. A proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 neutralizing antibody reduces serum cholesterol in mice and nonhuman primates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106: 9820–9825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ni Y. G., Condra J. H., Orsatti L., Shen X., Di Marco S., Pandit S., Bottomley M. J., Ruggeri L., Cummings R. T., Cubbon R. M., et al. 2010. A proprotein convertase subtilisin-like/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) C-terminal domain antibody antigen-binding fragment inhibits PCSK9 internalization and restores low density lipoprotein uptake. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 12882–12891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duff C. J., Scott M. J., Kirby I. T., Hutchinson S. E., Martin S. L., Hooper N. M. 2009. Antibody-mediated disruption of the interaction between PCSK9 and the low-density lipoprotein receptor. Biochem. J. 419: 577–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frank-Kamenetsky M., Grefhorst A., Anderson N. N., Racie T. S., Bramlage B., Akinc A., Butler D., Charisse K., Dorkin R., Fan Y., et al. 2008. Therapeutic RNAi targeting PCSK9 acutely lowers plasma cholesterol in rodents and LDL cholesterol in nonhuman primates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105: 11915–11920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liang H., Chaparro-Riggers J., Strop P., Geng T., Sutton J. E., Tsai D., Bai L., Abdiche Y., Dilley J., Yu J., et al. 2012. Proprotein convertase substilisin/kexin type 9 antagonism reduces low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in statin-treated hypercholesterolemic nonhuman primates. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 340: 228–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stein E. A., Honarpour N., Wasserman S. M., Xu F., Scott R., Raal F. J. 2013. Effect of the proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9 monoclonal antibody, AMG 145, in homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 128: 2113–2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stein E. A., Gipe D., Bergeron J., Gaudet D., Weiss R., Dufour R., Wu R., Pordy R. 2012. Effect of a monoclonal antibody to PCSK9, REGN727/SAR236553, to reduce low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia on stable statin dose with or without ezetimibe therapy: a phase 2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 380: 29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Giugliano R. P., Desai N. R., Kohli P., Rogers W. J., Somaratne R., Huang F., Liu T., Mohanavelu S., Hoffman E. B., McDonald S. T., et al. 2012. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of a monoclonal antibody to proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 in combination with a statin in patients with hypercholesterolaemia (LAPLACE-TIMI 57): a randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging, phase 2 study. Lancet. 380: 2007–2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sullivan D., Olsson A. G., Scott R., Kim J. B., Xue A., Gebski V., Wasserman S. M., Stein E. A. 2012. Effect of a monoclonal antibody to PCSK9 on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in statin-intolerant patients: the GAUSS randomized trial. JAMA. 308: 2497–2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blom D. J., Hala T., Bolognese M., Lillestol M. J., Toth P. D., Burgess L., Ceska R., Roth E., Koren M. J., Ballantyne C. M., et al. 2014. A 52-week placebo-controlled trial of evolocumab in hyperlipidemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 370: 1809–1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Robinson J. G., Nedergaard B. S., Rogers W. J., Fialkow J., Neutel J. M., Ramstad D., Somaratne R., Legg J. C., Nelson P., Scott R., et al. 2014. Effect of evolocumab or ezetimibe added to moderate- or high-intensity statin therapy on LDL-C lowering in patients with hypercholesterolemia: the LAPLACE-2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 311: 1870–1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirayama A., Honarpour N., Yoshida M., Yamashita S., Huang F., Wasserman S. M., Teramoto T. 2014. Effects of evolocumab (AMG 145), a monoclonal antibody to PCSK9, in hypercholesterolemic, statin-treated Japanese patients at high cardiovascular risk. Circ. J. 78: 1073–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roth E. M., McKenney J. M., Hanotin C., Asset G., Stein E. A. (2012) Atorvastatin with or without an antibody to PCSK9 in primary hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med. 367, 1891–1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stein E. A., Mellis S., Yancopoulos G. D., Stahl N., Logan D., Smith W. B., Lisbon E., Gutierrez M., Webb C., Wu R., et al. 2012. Effect of a monoclonal antibody to PCSK9 on LDL cholesterol. N. Engl. J. Med. 366: 1108–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fitzgerald K., Frank-Kamenetsky M., Shulga-Morskaya S., Liebow A., Bettencourt B. R., Sutherland J. E., Hutabarat R. M., Clausen V. A., Karsten V., Cehelsky J., et al. 2014. Effect of an RNA interference drug on the synthesis of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) and the concentration of serum LDL cholesterol in healthy volunteers: a randomised, single-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1 trial. Lancet. 383: 60–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stroes E., Colquhoun D., Sullivan D., Civeira F., Rosenson R. S., Watts G. F., Bruckert E., Cho L., Dent R., Knusel B., et al. 2014. Anti-PCSK9 antibody effectively lowers cholesterol in patients with statin intolerance: the GAUSS-2 randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 clinical trial of evolocumab. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 63: 2541–2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koren M. J., Lundqvist P., Bolognese M., Neutel J. M., Monsalvo M. L., Yang J., Kim J. B., Scott R., Wasserman S. M., Bays H. 2014. Anti-PCSK9 monotherapy for hypercholesterolemia: the MENDEL-2 randomized, controlled phase 3 clinical trial of evolocumab. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 63: 2531–2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hooper A. J., Burnett J. R. 2013. Anti-PCSK9 therapies for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 13: 429–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Awan Z., Choi H. Y., Stitziel N., Ruel I., Bamimore M. A., Husa R., Gagnon M. H., Wang R. H., Peloso G. M., Hegele R. A., et al. 2013. APOE p.Leu167del mutation in familial hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis. 231: 218–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marduel M., Ouguerram K., Serre V., Bonnefont-Rousselot D., Marques-Pinheiro A., Erik Berge K., Devillers M., Luc G., Lecerf J. M., Tosolini L., et al. 2013. Description of a large family with autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia associated with the APOE p.Leu167del mutation. Hum. Mutat. 34: 83–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Knijff P., van den Maagdenberg A. M., Stalenhoef A. F., Leuven J. A., Demacker P. N., Kuyt L. P., Frants R. R., Havekes L. M. 1991. Familial dysbetalipoproteinemia associated with apolipoprotein E3-Leiden in an extended multigeneration pedigree. J. Clin. Invest. 88: 643–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smit M., de Knijff P., van der Kooij-Meijs E., Groenendijk C., van den Maagdenberg A. M., Gevers Leuven J. A., Stalenhoef A. F., Stuyt P. M., Frants R. R., Havekes L. M. 1990. Genetic heterogeneity in familial dysbetalipoproteinemia. The E2(lys146----gln) variant results in a dominant mode of inheritance. J. Lipid Res. 31: 45–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Denis M., Marcinkiewicz J., Zaid A., Gauthier D., Poirier S., Lazure C., Seidah N. G., Prat A. 2012. Gene inactivation of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 reduces atherosclerosis in mice. Circulation. 125: 894–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van den Maagdenberg A. M., Hofker M. H., Krimpenfort P. J., de Bruijn I., van Vlijmen B., van der Boom H., Havekes L. M., Frants R. R. 1993. Transgenic mice carrying the apolipoprotein E3-Leiden gene exhibit hyperlipoproteinemia. J. Biol. Chem. 268: 10540–10545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zadelaar S., Kleemann R., Verschuren L., de Vries-Van der Weij J., van der Hoorn J., Princen H. M., Kooistra T. 2007. Mouse models for atherosclerosis and pharmaceutical modifiers. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27: 1706–1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van der Hoogt C. C., de Haan W., Westerterp M., Hoekstra M., Dallinga-Thie G. M., Romijn J. A., Princen H. M., Jukema J. W., Havekes L. M., Rensen P. C. 2007. Fenofibrate increases HDL-cholesterol by reducing cholesteryl ester transfer protein expression. J. Lipid Res. 48: 1763–1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van der Hoorn J. W., de Haan W., Berbee J. F., Havekes L. M., Jukema J. W., Rensen P. C., Princen H. M. 2008. Niacin increases HDL by reducing hepatic expression and plasma levels of cholesteryl ester transfer protein in APOE*3Leiden.CETP mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28: 2016–2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Haan W., de Vries-van der Weij J., van der Hoorn J. W., Gautier T., van der Hoogt C. C., Westerterp M., Romijn J. A., Jukema J. W., Havekes L. M., Princen H. M., et al. 2008. Torcetrapib does not reduce atherosclerosis beyond atorvastatin and induces more proinflammatory lesions than atorvastatin. Circulation. 117: 2515–2522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Westerterp M., van der Hoogt C. C., de Haan W., Offerman E. H., Dallinga-Thie G. M., Jukema J. W., Havekes L. M., Rensen P. C. 2006. Cholesteryl ester transfer protein decreases high-density lipoprotein and severely aggravates atherosclerosis in APOE*3-Leiden mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26: 2552–2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Delsing D. J., Offerman E. H., van Duyvenvoorde W., van Der Boom H., de Wit E. C., Gijbels M. J., van Der Laarse A., Jukema J. W., Havekes L. M., Princen H. M. 2001. Acyl-CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase inhibitor avasimibe reduces atherosclerosis in addition to its cholesterol-lowering effect in ApoE*3-Leiden mice. Circulation. 103: 1778–1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kühnast S., van der Hoorn J. W., van den Hoek A. M., Havekes L. M., Liau G., Jukema J. W., Princen H. M. 2012. Aliskiren inhibits atherosclerosis development and improves plaque stability in APOE*3Leiden.CETP transgenic mice with or without treatment with atorvastatin. J. Hypertens. 30: 107–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stary H. C., Chandler A. B., Dinsmore R. E., Fuster V., Glagov S., Insull W., Jr, Rosenfeld M. E., Schwartz C. J., Wagner W. D., Wissler R. W. 1995. A definition of advanced types of atherosclerotic lesions and a histological classification of atherosclerosis. A report from the Committee on Vascular Lesions of the Council on Arteriosclerosis, American Heart Association. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 15: 1512–1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fan D., Yancey P. G., Qiu S., Ding L., Weeber E. J., Linton M. F., Fazio S. 2008. Self-association of human PCSK9 correlates with its LDLR-degrading activity. Biochemistry. 47: 1631–1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tavori H., Fan D., Blakemore J. L., Yancey P. G., Ding L., Linton M. F., Fazio S. 2013. Serum proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 and cell surface low-density lipoprotein receptor: evidence for a reciprocal regulation. Circulation. 127: 2403–2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Plump A. S., Smith J. D., Hayek T., Aalto-Setala K., Walsh A., Verstuyft J. G., Rubin E. M., Breslow J. L. 1992. Severe hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice created by homologous recombination in ES cells. Cell. 71: 343–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van Dijk K. W., Hofker M. H., Havekes L. M. 1999. Dissection of the complex role of apolipoprotein E in lipoprotein metabolism and atherosclerosis using mouse models. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 1: 101–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ishibashi S., Herz J., Maeda N., Goldstein J. L., Brown M. S. 1994. The two-receptor model of lipoprotein clearance: tests of the hypothesis in “knockout” mice lacking the low density lipoprotein receptor, apolipoprotein E, or both proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91: 4431–4435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Breslow J. L. 1996. Mouse models of atherosclerosis. Science. 272: 685–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sun X. M., Eden E. R., Tosi I., Neuwirth C. K., Wile D., Naoumova R. P., Soutar A. K. 2005. Evidence for effect of mutant PCSK9 on apolipoprotein B secretion as the cause of unusually severe dominant hypercholesterolaemia. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14: 1161–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Herbert B., Patel D., Waddington S. N., Eden E. R., McAleenan A., Sun X. M., Soutar A. K. 2010. Increased secretion of lipoproteins in transgenic mice expressing human D374Y PCSK9 under physiological genetic control. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30: 1333–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Roubtsova A., Munkonda M. N., Awan Z., Marcinkiewicz J., Chamberland A., Lazure C., Cianflone K., Seidah N. G., Prat A. 2011. Circulating proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9 (PCSK9) regulates VLDLR protein and triglyceride accumulation in visceral adipose tissue. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 31: 785–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Poirier S., Mayer G., Benjannet S., Bergeron E., Marcinkiewicz J., Nassoury N., Mayer H., Nimpf J., Prat A., Seidah N. G. 2008. The proprotein convertase PCSK9 induces the degradation of low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) and its closest family members VLDLR and ApoER2. J. Biol. Chem. 283: 2363–2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Canuel M., Sun X., Asselin M. C., Paramithiotis E., Prat A., Seidah N. G. 2013. Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) can mediate degradation of the low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP-1). PLoS ONE. 8: e64145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Espirito Santo S. M., Rensen P. C., Goudriaan J. R., Bensadoun A., Bovenschen N., Voshol P. J., Havekes L. M., van Vlijmen B. J. 2005. Triglyceride-rich lipoprotein metabolism in unique VLDL receptor, LDL receptor, and LRP triple-deficient mice. J. Lipid Res. 46: 1097–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Le May C., Berger J. M., Lespine A., Pillot B., Prieur X., Letessier E., Hussain M. M., Collet X., Cariou B., Costet P. 2013. Transintestinal cholesterol excretion is an active metabolic process modulated by PCSK9 and statin involving ABCB1. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 33: 1484–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mortimer B. C., Beveridge D. J., Martins I. J., Redgrave T. G. 1995. Intracellular localization and metabolism of chylomicron remnants in the livers of low density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice and apoE-deficient mice. Evidence for slow metabolism via an alternative apoE-dependent pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 270: 28767–28776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ishibashi S., Perrey S., Chen Z., Osuga J., Shimada M., Ohashi K., Harada K., Yazaki Y., Yamada N. 1996. Role of the low density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor pathway in the metabolism of chylomicron remnants. A quantitative study in knockout mice lacking the LDL receptor, apolipoprotein E, or both. J. Biol. Chem. 271: 22422–22427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.van der Hoorn J. W., Kleemann R., Havekes L. M., Kooistra T., Princen H. M., Jukema J. W. 2007. Olmesartan and pravastatin additively reduce development of atherosclerosis in APOE*3Leiden transgenic mice. J. Hypertens. 25: 2454–2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kooistra T., Verschuren L., de Vries-van der Weij J., Koenig W., Toet K., Princen H. M., Kleemann R. 2006. Fenofibrate reduces atherogenesis in ApoE*3Leiden mice: evidence for multiple antiatherogenic effects besides lowering plasma cholesterol. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26: 2322–2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kleemann R., Princen H. M., Emeis J. J., Jukema J. W., Fontijn R. D., Horrevoets A. J., Kooistra T., Havekes L. M. 2003. Rosuvastatin reduces atherosclerosis development beyond and independent of its plasma cholesterol-lowering effect in APOE*3-Leiden transgenic mice: evidence for antiinflammatory effects of rosuvastatin. Circulation. 108: 1368–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jiang X. C., Agellon L. B., Walsh A., Breslow J. L., Tall A. 1992. Dietary cholesterol increases transcription of the human cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene in transgenic mice. Dependence on natural flanking sequences. J. Clin. Invest. 90: 1290–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.van den Hoek A. M., van der Hoorn J. W., Maas A. C., van den Hoogen R. M., van Nieuwkoop A., Droog S., Offerman E. H., Pieterman E. J., Havekes L. M., Princen H. M. 2014. APOE*3Leiden.CETP transgenic mice as model for pharmaceutical treatment of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 16: 537–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ferri N., Tibolla G., Pirillo A., Cipollone F., Mezzetti A., Pacia S., Corsini A., Catapano A. L. 2012. Proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9 (PCSK9) secreted by cultured smooth muscle cells reduces macrophages LDLR levels. Atherosclerosis. 220: 381–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shen L., Peng H. C., Nees S. N., Zhao S. P., Xu D. Y. 2013. Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 potentially influences cholesterol uptake in macrophages and reverse cholesterol transport. FEBS Lett. 587: 1271–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Baigent C., Blackwell L., Emberson J., Holland L. E., Reith C., Bhala N., Peto R., Barnes E. H., Keech A., Simes J., et al. 2010. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 376: 1670–1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.