Abstract

Introduction

A multicenter, open-label phase III study was conducted to test whether sunitinib plus paclitaxel prolongs progression-free survival (PFS) compared with bevacizumab plus paclitaxel as first-line treatment for patients with HER2− advanced breast cancer.

Patients and Methods

Patients with HER2− advanced breast cancer who were disease free for ≥ 12 months after adjuvant taxane treatment were randomized (1:1; planned enrollment 740 patients) to receive intravenous (I.V.) paclitaxel 90 mg/m2 every week for 3 weeks in 4-week cycles plus either sunitinib 25 to 37.5 mg every day or bevacizumab 10 mg/kg I.V. every 2 weeks.

Results

The trial was terminated early because of futility in reaching the primary endpoint as determined by the independent data monitoring committee during an interim futility analysis. At data cutoff, 242 patients had been randomized to sunitinib-paclitaxel and 243 patients to bevacizumab-paclitaxel. Median PFS was shorter with sunitinib-paclitaxel (7.4 vs. 9.2 months; hazard ratio [HR] 1.63 [95% confidence interval (CI), 1.18–2.25]; 1-sided P = .999). At a median follow-up of 8.1 months, with 79% of sunitinib-paclitaxel and 87% of bevacizumab-paclitaxel patients alive, overall survival analysis favored bevacizumab-paclitaxel (HR 1.82 [95% CI, 1.16–2.86]; 1-sided P = .996). The objective response rate was 32% in both arms, but median duration of response was shorter with sunitinib-paclitaxel (6.3 vs. 14.8 months). Bevacizumab-paclitaxel was better tolerated than sunitinib-paclitaxel. This was primarily due to a high frequency of grade 3/4, treatment-related neutropenia with sunitinib-paclitaxel (52%) precluding delivery of the prescribed doses of both drugs.

Conclusion

The sunitinib-paclitaxel regimen evaluated in this study was clinically inferior to the bevacizumab-paclitaxel regimen and is not a recommended treatment option for patients with advanced breast cancer.

Keywords: Advanced breast cancer, Bevacizumab, Paclitaxel, Sunitinib malate, Tyrosine kinase inhibitor

Introduction

Paclitaxel is active in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer, whether delivered every week (qw) or every 3 weeks (q3w).1–3 Addition of bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody specific for vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), to paclitaxel therapy (given qw for 3 weeks in 4-week cycles) prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) compared with paclitaxel alone (median 11.8 vs. 5.9 months; hazard ratio [HR] 0.60; P < .001) as first-line treatment for HER2− metastatic disease in a phase III study,4 which led to regulatory approval of this combination. Other clinical trials with bevacizumab and taxanes showed PFS improvements of 1 to 2 months, lending further support for the combination of antiangiogenic agents with taxane chemotherapy as treatment for metastatic breast cancer.5,6

The platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) signaling pathway has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of breast cancer. High levels of both PDGF and PDGF receptor (PDGFR)-β have been found to correlate with poor prognosis in this disease.7,8 In preclinical solid tumor models, dual inhibition of VEGF and PDGF signaling pathways was found to be synergistic in blocking tumor growth when compared with inhibition of either pathway alone.9,10

Sunitinib malate is an oral multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor with activity against VEGF receptors (VEGFRs) −1, −2 and −3 and PDGFR-α and -β, as well as stem-cell factor receptor (KIT), FMS- like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3), colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF-1R), and glial cell line—derived neurotrophic factor receptor (rearranged during transfection [RET; Pfizer Inc., New York, NY; data on file]).11–15 Sunitinib is approved worldwide for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and for gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) after progression while taking or intolerance to imatinib treatment. In preclinical breast cancer models, sunitinib has been shown to inhibit tumor growth and increase survival both alone and in combination with standard chemotherapy.14,16

A phase II study of single-agent sunitinib, using the approved dosing schedule of 50 mg/day given in 6-week cycles of 4 weeks on treatment followed by 2 weeks off (schedule 4/2), demonstrated activity (objective response rate [ORR], 11%) in patients with heavily pretreated metastatic breast cancer (n = 64).17 he feasibility of an alternative sunitinib dosing schedule (37.5 mg on continuous daily dosing [CDD]) has been reported in several studies involving patients with RCC or GIST.18–20 An exploratory study investigated the combination of sunitinib (25 mg with escalation to 37.5 mg as tolerated on the CDD schedule) with paclitaxel (90 mg/m2 given qw for 3 weeks in 4-week cycles) in patients with metastatic or locally advanced breast cancer.21 With administration of a median of 6 cycles of sunitinib and 5 cycles of paclitaxel, this study found that the sunitinib-paclitaxel combination was well tolerated and showed evidence of antitumor activity (ORR, 39% in 18 patients with measurable disease at baseline).

We hypothesized that inhibition of multiple signaling pathways using a multitargeted agent such as sunitinib would yield a long-term efficacy benefit superior to that of bevacizumab when combined with paclitaxel in advanced breast cancer. In this article we report the final results of a multicenter randomized open-label phase III trial designed to test the hypothesis that the PFS of patients receiving sunitinib plus paclitaxel would be superior to that of patients receiving bevacizumab plus paclitaxel as first-line treatment for HER2− advanced breast cancer (defined as metastatic or locally recurrent disease). The trial was terminated early because of futility in reaching its primary endpoint as determined by the independent data monitoring committee (DMC) at the first interim analysis.

Methods

Patients

The study population was composed of female patients and 1 male patient ≥ 18 years of age with unresectable histologically or cytologically proven advanced breast cancer that was measurable based on Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST)22 or bone- only disease. Eligible patients had HER2− disease (or HER2+ disease that had failed to resolve on trastuzumab treatment or HER2+ disease and contraindications for trastuzumab). Patients who had bone-only disease and were hormone receptor-positive (HR+ ) were required to have disease that had progressed on hormone therapy. Patients were required to have an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) of 0 or 1 with adequate organ function and resolution of acute toxic effects of previous therapy or surgical procedures to National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0 (NCI CTCAE v3.0) grade ≤ 1 (except alopecia). Patients could have received any type of adjuvant treatment before entering the trial, except adjuvant taxane treatment unless they had been disease free for ≥ 12 months after treatment. In addition patients could not have received previous treatment with any cytotoxic anticancer therapies for advanced disease or previous treatment with bevacizumab or sunitinib, nor could they have been candidates for curative therapies. Brain metastases and cardiovascular disease or uncontrolled hypertension were also criteria for exclusion.

This study was conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, the declaration of Helsinki, and applicable local regulatory requirements and laws. Approval from the institutional review board or independent ethics committee of each participating center was required, and all patients gave written informed consent before enrollment.

Study Design

Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive sunitinib plus paclitaxel or bevacizumab plus paclitaxel on an open-label basis because of the differing routes of sunitinib and bevacizumab administration. Patients were stratified based on previous neoadjuvant/adjuvant therapy (yes/no), hormone receptor status (+/−), and disease-free interval ( ≤ 24 months or > 24 months). The primary endpoint was PFS, defined as time from randomization to first documented tumor progression or death while in the study from any cause, whichever occurred first. Secondary endpoints included ORR, duration of response, overall survival (OS), 1- to 3-year survival, and safety.

Study Treatment

Treatment was administered in 4-week cycles. In both treatment arms, paclitaxel was administered intravenously at a starting dose of 90 mg/m2 as a 1-hour nusionqw for 3 weeks followed by 1 week off treatment. The paclitaxel dose could be reduced to 65 mg/m2 after the first cycle depending on individual tolerability. Patients were pretreated with standard medications before paclitaxel administration. Bevacizumab 10 mg/kg was administered by intravenous infusion every 2 weeks. Patients received sunitinib at a starting dose of 25 mg orally on the CDD schedule. After successful administration of paclitaxel at 90 mg/m2 and no complicated neutropenia (prolonged or associated with fever or infection) during the first cycle of treatment, the sunitinib dose could be increased to 37.5 mg/day in the second or subsequent cycles at the investigator’s discretion. Interruptions in sunitinib dosing of 1 to 4 weeks were permitted for treatment-related dose-limiting toxicities, and dose reductions to 12.5 mg were permitted as necessary.

Hematopoietic growth factor use was permitted prophylactically and if the absolute neutrophil count was ≤ 1500/µL. Treatment with sunitinib could continue during granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) therapy except in cases of complicated neutropenia.

Paclitaxel could be discontinued at the investigator’s discretion because of toxicity or if it was determined that maximum benefit had been achieved. In such instances single-agent sunitinib or bevacizumab therapy (as randomized) was to be continued until disease progression or patient withdrawal from the study.

Assessments

Tumors were imaged using computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging at baseline and at 8-week intervals, or whenever disease progression was suspected, to confirm response based on RECIST. In addition, imaging was performed at the end of treatment/withdrawal visit. Bone scans were performed every 16 weeks in all patients. In patients with bone-only disease, an additional bone scan was performed at week 8 to detect radiographic “flare” reactions and to set a new baseline for subsequent assessments. Safety was assessed overall by physical examination and analysis of adverse events (AEs; graded using NCI CTCAE v3.0), hematologic tests, blood chemistry tests, and vital signs at regular intervals. Thyroid-stimulating hormone levels were measured at screening and as clinically indicated thereafter. QTc intervals were determined using triplicate 12-lead electrocardiography at screening, on day 15 of the first treatment cycle, 2 weeks after a dose modification, as clinically indicated, and at the end of treatment. Left ventricular ejection fraction was assessed using 2-dimensional echocardiography or multigated acquisition scanning at screening, on day 1 of cycle 2 for patients with previous anthracycline exposure, every 3 months and as clinically indicated, and at the end of treatment.

Statistical Analyses

The sample size was determined based on the assumption that in the first-line setting sunitinib and paclitaxel would improve PFS by 30% compared with bevacizumab plus paclitaxel. Evaluation of 513 events in the 2 treatment arms using a 1-sided unstratified log-rank test was required for a significance level of 0.025 and a power of 0.80 to detect a difference, for which it was determined that approximately 740 patients (370 per treatment arm) would be randomized. Interim analyses were planned when 30% and 67% of PFS events had occurred to allow the trial to be stopped early for futility or safety; in addition the second analysis allowed the trial to be stopped early for efficacy.

The intention-to-treat (ITT) population was the primary population for evaluating all efficacy parameters (except for duration of response, which was assessed only in responders) and patient characteristics. The safety population comprised all patients who received at least 1 dose of study medication, with treatment assignments designated according to actual treatment received. Time-to-event end-points (PFS, duration of response, and OS) were summarized using the Kaplan-Meier method, and between-treatment comparisons for PFS and OS were conducted using 1-sided stratified and unstratified log-rank tests at the α = 0.025 overall significance level. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient characteristics, treatment administration, tumor response, and safety parameters.

Role of the Study Sponsor

This study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00373256; SUN 1094) was designed and managed by Pfizer Inc. Data were collected and analyzed by Pfizer in collaboration with the team of investigators. All authors had full access to the data and final responsibility for approving this manuscript for publication.

Results

Study Conduct, Patient Characteristics, and Treatment Summary

As part of an ongoing safety and efficacy review by the DMC, an interim futility analysis was conducted on May 27, 2009 with 27% of accrued events. The prespecified futility boundary was an observed upper boundary of the 90% confidence interval (CI) of the HR ≥ 1.15. Based on the available PFS data, the HR was found to be 1.73 (95% CI, 1.22–2.43) favoring the bevacizumab combination arm. With the futility boundary having been crossed, the DMC recommended that trial enrollment be stopped.

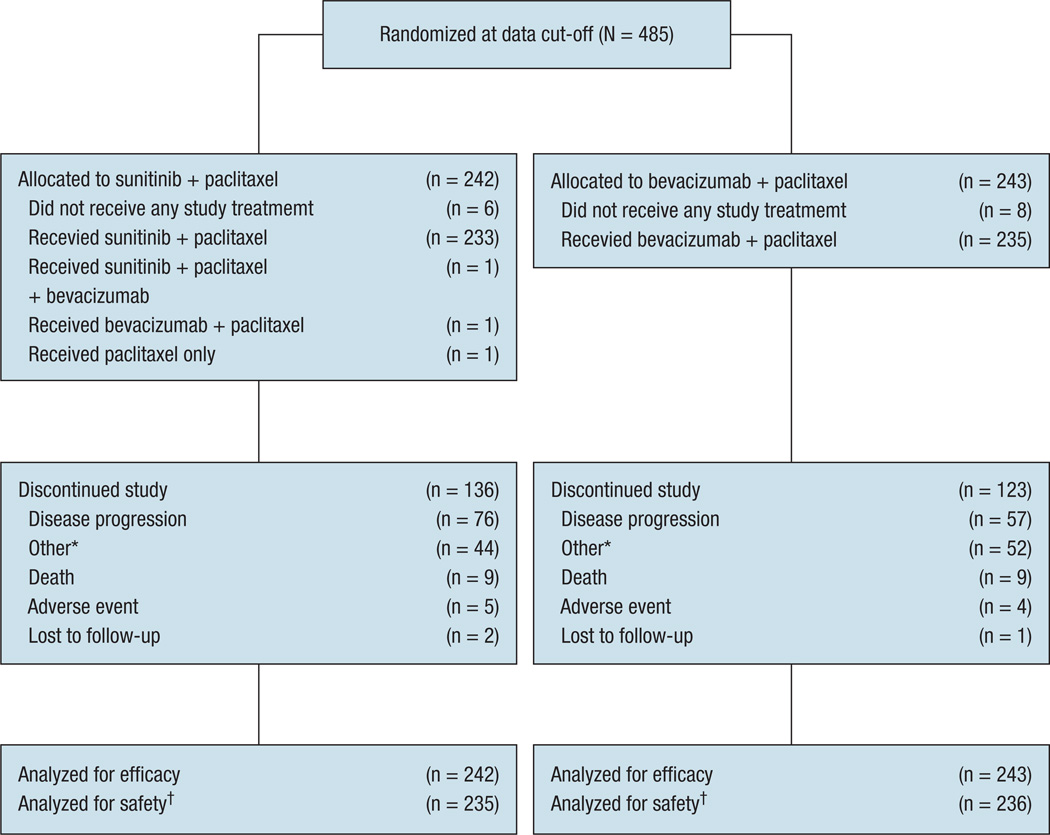

Between November 7, 2006 and June 1, 2009 (data cutoff), 485 patients were randomized at 109 centers in 4 countries (Germany, Italy, Spain, and the United States). Of these patients, 242 were randomized to the sunitinib combination arm and 243 to the bevacizumab combination arm (ITT population; Figure 1). Six patients in the sunitinib combination arm and 8 in the bevacizumab combination arm did not receive any study treatment at all (due to withdrawal of consent after randomization) or did not receive treatment before data cutoff. The safety populations comprised 235 patients in the sunitinib combination arm and 236 in the bevacizumab combination arm. At data cutoff a total of136and 123 patients had discontinued the study, whereas 106 and 120 patients were still receiving treatment in the sunitinib and bevacizumab combination arms, respectively (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient Disposition (CONSORT Flow Diagram)

*Includes withdrawal of consent, physician’s decision, disease progression, patient achieved best response, new therapy started, patient received maximum benefit, patient refused treatment, global deterioration of health status, and missing data. †For the purposes of the safety analysis, the patient who inadvertently received bevacizumab plus paclitaxelin the sunitinib combination arm was included in the bevacizumab plus paclitaxel safety population.

Patient demographic characteristics, disease, and previous treatment characteristics were well balanced in the 2 treatment arms (Table 1). The majority of patients in both arms had received previous adjuvant chemotherapy (68% and 67%, respectively). Exposure to study drugs is summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics at Baseline

| Patient Characteristic | Sunitinib + Paclitaxel (N = 242) |

Bevacizumab + Paclitaxel (N = 243) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| Median | 57 | 57 |

| Range | 27–84 | 32–92 |

| ECOG Performance Status n (%) | ||

| 0 | 135 (56) | 143 (59) |

| 1 | 104 (43) | 95 (39) |

| 2 | 2 (1) | 5 (2) |

| Missing | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| Extent of Disease, n (%) | ||

| Metastatic | 240 (99) | 240 (99) |

| Locally recurrent | 2 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Histology, n (%) | ||

| Ductal | 208 (86) | 200 (82) |

| Lobular | 26 (11) | 31 (13) |

| Other | 8 (3) | 12 (5) |

| Receptor Status, n (%) | ||

| Hormone receptor-positive | 183 (76) | 185 (76) |

| HER2−* | 234 (97) | 236 (97) |

| Triple negative | 51 (21) | 52 (21) |

| Previous Neoadjuvant/Adjuvant Chemotherapy,†n (%) | 165 (68) | 163 (67) |

| Disease-free Interval, n (%) | ||

| ≤ 24 months | 113 (47) | 115 (47) |

| > 24 months | 129 (53) | 128 (53) |

Abbreviations: ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; triple negative = hormone receptor-negative and HER2−

Determined using fluorescence in situ hybridization, chromogenic in situ hybridization, and immunohistochemistry; 3 patients unknown/not determined in each arm; patients with HER2+ disease were included in the study based on either disease progression on previous trastuzumab therapy or contraindications for trastuzumab.

Although neoadjuvant therapy was permitted (if the patient was disease free for ≥ 12 months after treatment), all previous chemotherapy was administered in the adjuvant setting.

Table 2.

Study Drug Exposure

| Sunitinib + Paclitaxel | Bevacizumab + Paclitaxel | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sunitinib (N = 234)* |

Paclitaxel (N = 235) |

Bevacizumab (N = 236) |

Paclitaxel (N = 236) |

|

| Median no. of Days Drug Administered (range)† | 97 (1–494) | 11 (1–46) | 9 (1–51) | 15 (1–61) |

| Median Total Dose Administered (range) | 2344 mg (12.5‡-15,800) | 944 mg/m2 (87–4020) | 93 mg/kg (9–612) | 1225 mg/m2 (68–5280) |

| Dosing Interruptions§ | ||||

| Patients, n (%) | 113 (48) | 116 (49) | 88 (37) | 91 (39) |

| Median duration (range), days | 9 (3–48) | 7 (3–14) | 14 (10–18) | 7 (3–14) |

| Dose Reductions | ||||

| Patients, n (%) | 83 (35) | 120 (51) | 9 (4)¶ | 79 (34) |

| Median Relative Dose Intensity (range), %** | 62 (2–107) | 80 (32–109) | 91 (46–145)†† | 89 (25–109) |

One patient inadvertently received bevacizumab instead of sunitinib and was not included in this analysis.

Expected number of days of administered treatment per cycle was 28 for sunitinib, 3 for paclitaxel, and 2 for bevacizumab.

Since sunitinib can only be dosed in increments of 12.5 mg, this value has not been rounded.

Defined as ≥ 3 consecutive days sunitinib was not given, failure to give any of the 3 planned paclitaxel doses or a delay ≥ 10 days between paclitaxel doses per 4-week cycle, or failure to give any of the 2 planned bevacizumab doses or ≥ 17 days between bevacizumab doses per 4-week cycle.

Includes patients whose bevacizumab dose was reduced on recalculation because of weight changes and patients who received < 10 mg/kg bevacizumab per the investigator’s decision.

For sunitinib, the target dose was assumed to be 25 mg/day in cycle 1 and 37.5 mg/day thereafter; for paclitaxel, the target dose was based on body surface area and assigned dose level.

Overestimated in 1 patient because of a data-entry error; 2 patients received more than the intended dose.

Efficacy

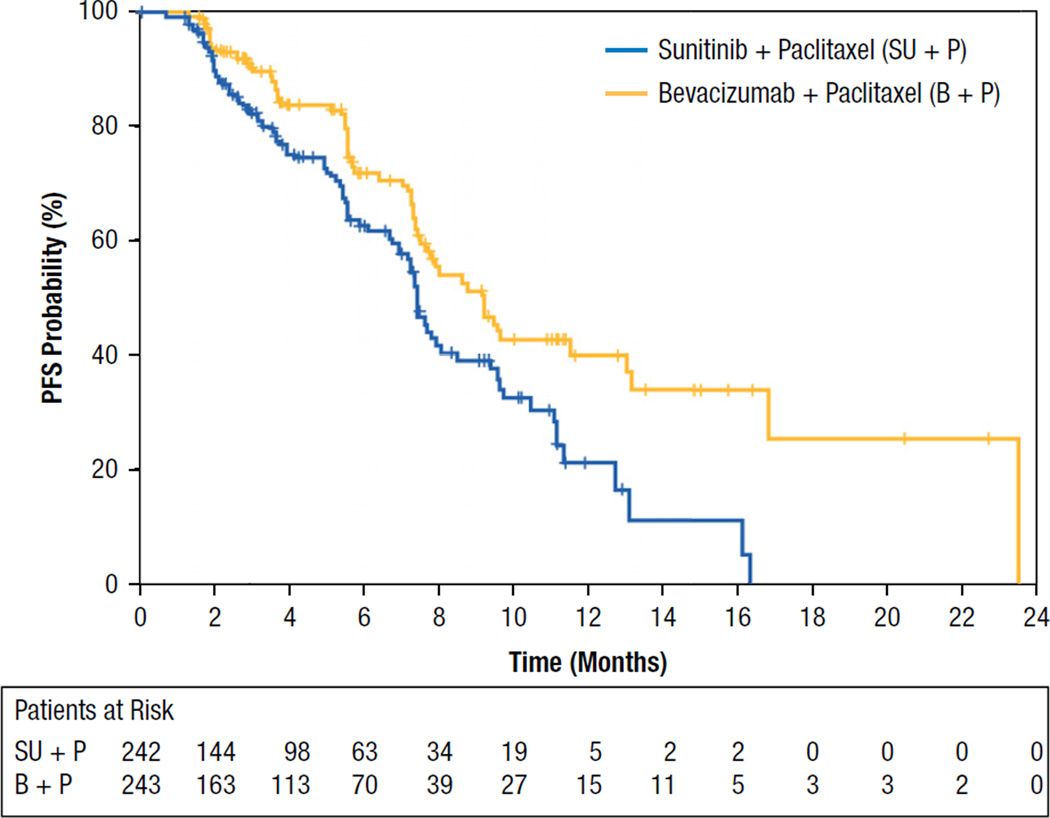

Final efficacy results are presented in Table 3. The primary end-point, median PFS, was 7.4 months (95% CI, 6.9–8.5) in the sunitinib combination arm compared with 9.2 months (95% CI, 7.7–13.0) in the bevacizumab combination arm (Figure 2). The HR of 1.63 (stratified analysis) favored the bevacizumab combination arm (95% CI, 1.18–2.25; 1-sided log-rank P = .999). Thirty-seven percent and 29% of patients in the sunitinib and bevacizumab combination arms, respectively, had experienced disease progression or died.

Table 3.

Efficacy Results

| Variable | Sunitinib + Paclitaxel (N = 242) |

Bevacizumab + Paclitaxel (N = 243) |

Hazard Ratio | 95% CI of Hazard Ratio |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Progression-free Survival | |||||

| Events, n (%) | 89 (37) | 70 (29) | |||

| Median, months (95% CI) | 7.4 (6.9–8.5) | 9.2 (7.7–13.0) | |||

| Stratified analysis* | 1.63 | 1.18–2.25 | .999† | ||

| Overall Survival | |||||

| Events, n (%) | 52 (21) | 32 (13) | |||

| Median, months (95% CI) | 17.6 (16.4-NR) | NR (22.1-NR) | |||

| Stratified analysis* | 1.82 | 1.16–2.86 | .996† | ||

| Objective Responses, n (%) | 78 (32.2) | 78 (32.1) | |||

| 95% CI‡ | 26–39 | 26–38 | |||

| Stratified analysis* | 1.01§ | 0.67–1.50¶ | .525** | ||

| Duration of Response | |||||

| Observations, n (%)†† | 35 (45) | 24 (31) | |||

| Median, months‡ | 6.3 | 14.8 | |||

| 95% CI | 5.6–7.9 | 7.4–21.7 |

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; NR = not yet reached; objective responses = complete responses and partial responses

Stratified by randomization factors.

One-sided log-rank test.

Based on Kaplan-Meier estimates.

Odds ratio.

95% exact CI.

One-sided exact test.

Responders who subsequently experienced disease progression or death.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier Estimates of Progression-free Survival

Analysis of the stratification factors used for randomization and other baseline characteristics indicated that in most subgroups, median PFS was shorter in the sunitinib than in the bevacizumab combination arm. Exceptions to this, whereby similar treatment effects between the sunitinib plus paclitaxel arm and the bevacizumab plus paclitaxel arm were observed, were found for 3 subgroups of patients: (1) patients with triple-negative (HR− and HER2− ) disease (6.9 vs. 5.7 months), (2) patient age of ≥ 65 years (8.0 vs. 7.9 months), and (3) patients of nonwhite race (6.9 vs. 5.5 months). For all other subgroups the treatment effect favored the bevacizumab plus paclitaxel arm.

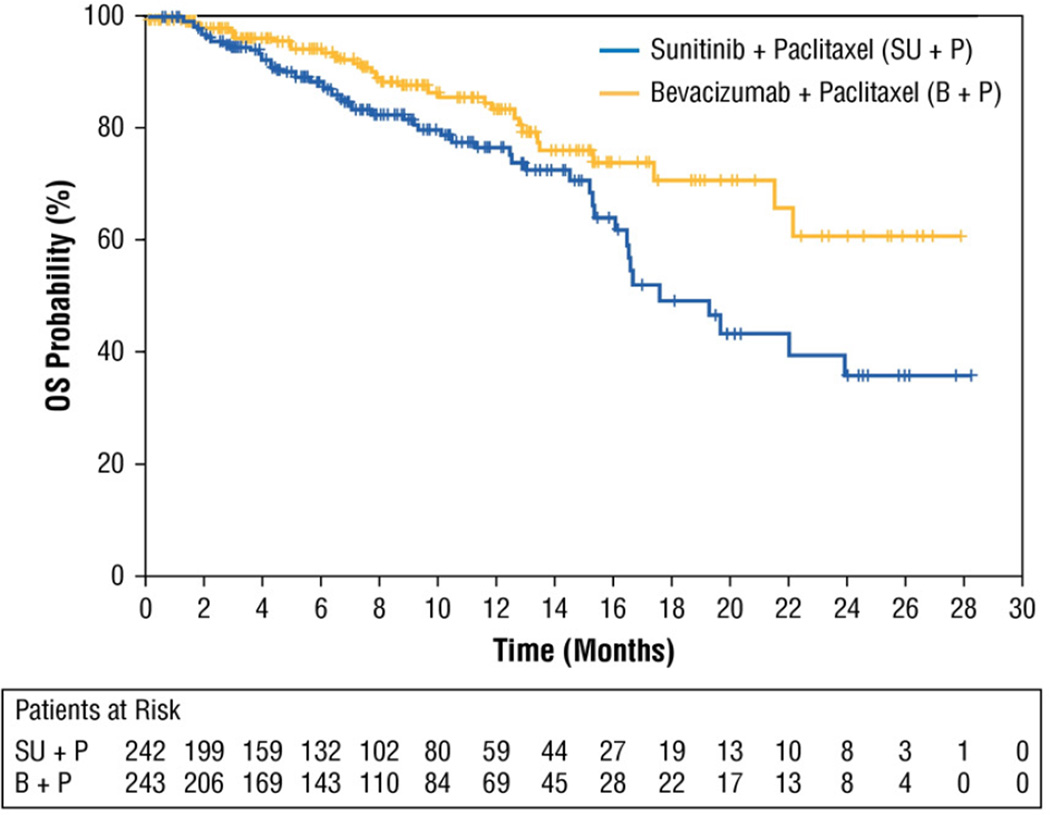

At data cutoff, with a median follow-up of 8.1 months (95% CI, 7.5–8.9), 79% and 87% of patients in the sunitinib and bevacizumab combination arms, respectively, were alive. Stratified analysis of OS at this early time point yielded a HR of 1.82 favoring the bevacizumab combination arm (95% CI, 1.16–2.86; 1-sided log-rank P = .996) (Table 3, Figure 3). The probability of survival at 1 year was 77% (95% CI, 69–83) in the sunitinib combination arm vs. 84% (95% CI, 76–89) in the bevacizumab combination arm, and at 2 years it was 36% (95% CI, 21–50) vs. 61% (95% CI, 43–75). The probability of survival at 3 years could not be calculated because of insufficient data.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier Estimates of Overall Survival

ORRs were 32.2% in the sunitinib combination arm and 32.1% in the bevacizumab combination arm (stratified odds ratio, 1.01; 1-sided exact P = .525) (Table 3). The median duration of response was 6.3 months (95% CI, 5.6–7.9) and 14.8 months (95% CI, 7.4–21.7) in the sunitinib and bevacizumab combination arms, respectively.

Safety

Treatment-related AEs and hematologic laboratory abnormalities reported are shown in Table 4. The most frequently reported AEs were neutropenia (69%), fatigue (55%), and diarrhea (54%) in the sunitinib combination arm and alopecia (54%), fatigue (51%), and peripheral neuropathy (40%) in the bevacizumab combination arm. AEs that were reported ≥ 10% more frequently in the sunitinib combination arm than in the bevacizumab combination arm were neutropenia, diarrhea, nausea, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and hand-foot syndrome. Only nail disorders were reported ≥ 10% more frequently in the bevacizumab combination arm. Likewise the frequencies of all hematologic laboratory abnormalities were considerably higher with sunitinib plus paclitaxel than with bevacizumab plus paclitaxel.

Table 4.

Treatment-related Adverse Events and Hematologic Laboratory Abnormalities

| Adverse Event or Laboratory Abnormality |

n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sunitinib + Paclitaxel (N = 235) | Bevacizumab + Paclitaxel (N = 236) | |||||

| Any Grade |

Grade 3 |

Grade 4 |

Any Grade |

Grade 3 |

Grade 4 |

|

| Treatment-related Adverse Events* Reported in ≥ 10% of Patients in Either Treatment Arm | ||||||

| Any Adverse Event | 227 (97) | 130 (55) | 52 (22) | 224 (95) | 105 (44) | 19 (8) |

| Neutropenia | 161 (69) | 91 (39) | 32 (14) | 84 (36) | 36 (15) | 12 (5) |

| Fatigue | 130 (55) | 28 (12) | 1 (0.4) | 121 (51) | 18 (8) | 1 (0.4) |

| Diarrhea | 128 (54) | 21 (9) | 1 (0.4) | 75 (32) | 6 (3) | 0 |

| Alopecia | 113 (48) | 4 (2) | 0 | 127 (54) | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Nausea | 105 (45) | 6 (3) | 0 | 83 (35) | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Anemia | 89 (38) | 13 (6) | 1 (0.4) | 51 (22) | 5 (2) | 1 (0.4) |

| Peripheral Neuropathy | 79 (34) | 19 (8) | 0 | 94 (40) | 35 (15) | 0 |

| Dysgeusia | 57 (24) | 0 | 0 | 49 (21) | 0 | 1 (0.4) |

| Leukopenia | 57 (24) | 23 (10) | 5 (2) | 48 (20) | 13 (6) | 4 (2) |

| Rash | 55 (23) | 6 (3) | 0 | 38 (16) | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Epistaxis | 53 (23) | 2 (1) | 0 | 76 (32) | 0 | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 53 (23) | 9 (4) | 1 (0.4) | 12 (5) | 2 (1) | 1 (0.4) |

| Mucosal Inflammation | 48 (20) | 7 (3) | 0 | 50 (21) | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Vomiting | 46 (20) | 5 (2) | 0 | 32 (14) | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Anorexia | 42 (18) | 0 | 0 | 31 (13) | 4 (2) | 0 |

| Stomatitis | 40 (17) | 7 (3) | 0 | 20 (8) | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| Constipation | 38 (16) | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 42 (18) | 0 | 0 |

| Hypertension | 37 (16) | 7 (3) | 0 | 56 (24) | 24 (10) | 0 |

| Dyspepsia | 30 (13) | 3 (1) | 0 | 15 (6) | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Hand–foot Syndrome | 26 (11) | 10 (4) | 0 | 3 (1) | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| Asthenia | 25 (11) | 3 (1) | 2 (1) | 13 (6) | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| Arthralgia | 23 (10) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 28 (12) | 0 | 0 |

| Dyspnea | 23 (10) | 4 (2) | 0 | 16 (7) | 3 (1) | 0 |

| Peripheral Sensory Neuropathy | 21 (9) | 6 (3) | 0 | 29 (12) | 7 (3) | 0 |

| Headache | 20 (9) | 2 (1) | 0 | 29 (12) | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| Myalgia | 20 (9) | 2 (1) | 1 (0.4) | 29 (12) | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| Nail Disorder | 12 (5) | 0 | 0 | 37 (16) | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| Hematologic Laboratory Abnormalities (Decreases)*† | ||||||

| Leukocytes | 219 (95) | 88 (38) | 17 (7) | 184 (79) | 42 (18) | 5 (2) |

| Neutrophils | 203 (88) | 102 (44) | 39 (17) | 149 (64) | 40 (17) | 17 (7) |

| Hemoglobin | 198 (86) | 12 (5) | 0 | 175 (75) | 7 (3) | 0 |

| Lymphocytes | 152 (66) | 64 (28) | 5 (2) | 121 (52) | 30 (13) | 7 (3) |

| Platelets | 116 (50) | 11 (5) | 2 (1) | 32 (14) | 3 (1) | 2 (1) |

Maximum National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events grade.

n = 231 (sunitinib + paclitaxel) and 233 (bevacizumab + paclitaxel).

A higher frequency of grade 3/4 treatment-related AEs was reported in the sunitinib combination arm (77%) than in the bevacizumab combination arm (53%) (Table 4). Grade 3/4 treatment-related AEs reported in ≥ 5% of patients on sunitinib plus paclitaxel were neutropenia, fatigue, leukopenia, diarrhea, peripheral neuropathy, anemia, and febrile neutropenia. Of these, all except peripheral neuropathy and hypertension occurred at a minimally increased frequency with sunitinib plus paclitaxel. Most notably grade 3/4 treatment-related neutropenia was reported in 52% vs. 20% of patients in the sunitinib and bevacizumab combination arms. Grade 3/4 treatment-related AEs reported in ≥ 5% of patients receiving bevacizumab plus paclitaxel were neutropenia, peripheral neuropathy, hypertension, fatigue, and leukopenia. There were 9 on-study deaths in the sunitinib combination arm, 8 due to disease progression or underlying disease and 1 due to cardiogenic shock attributed to diabetes and sepsis. There were 6 on-study deaths in the bevacizumab combination arm, 4 due to disease progression that was not deemed related to treatment and 1 each due to acute pulmonary edema and septic shock, which were considered treatment-related.

Dosing interruptions or reductions due to an AE occurred more frequently with sunitinib plus paclitaxel than with bevacizumab plus paclitaxel (64% and 72% vs. 45% and 55% for each drug), in each case most commonly due to neutropenia (18% and 53% vs. 11% and 23%). Other AEs leading to interruptions/reductions in ≥ 10% of patients were diarrhea (12%, sunitinib) and leukopenia and thrombocytopenia (13% and 12%, respectively, paclitaxel) in the sunitinib combination arm and peripheral neuropathy (15%, paclitaxel) in the bevacizumab combination arm. Therapy discontinuations due to an AE were similar with sunitinib plus paclitaxel and bevacizumab plus paclitaxel (21% and 23% vs. 20% and 24% for each drug). In the sunitinib combination arm, the AE leading most frequently to discontinuation of both sunitinib and paclitaxel was fatigue (2% and 3%); in the bevacizumab combination arm, peripheral neuropathy most frequently led to discontinuation of both bevacizumab (2%) and paclitaxel (8%).

Discussion

The primary objective of this phase III study was the demonstration of superior PFS with sunitinib plus paclitaxel vs. bevacizumab plus paclitaxel as first-line treatment for HER2− advanced breast cancer. However statistical significance could not be established for the superiority of PFS with the combination of sunitinib plus paclitaxel compared with bevacizumab plus paclitaxel in this patient population and treatment setting (median PFS, 7.4 months vs. 9.2 months; HR 1.63; P = .999).

No improvement was found in any of the other efficacy endpoints with sunitinib plus paclitaxel in this study. Although interpretation of OS results was limited because of ongoing follow-up at the time of data cutoff, all available survival data favored the bevacizumab combination arm. ORRs were equivalent in the treatment arms, but the median duration of response was nearly twice as long in the bevacizumab combination arm as in the sunitinib combination arm. Likewise subgroup analyses based on stratification factors and other baseline characteristics failed to demonstrate a statistically significant improvement with the sunitinib-paclitaxel combination in any patient subpopulation, either for PFS or for the other efficacy endpoints.

There are several possible reasons that time-to-event endpoints, including OS and its surrogate endpoint PFS, were not superior for the combination of sunitinib plus paclitaxel compared with bevacizumab plus paclitaxel. First, the performance of the combination of bevacizumab plus paclitaxel may have been better than postulated in our initial study design. There is little evidence to support this, as the median PFS obtained with bevacizumab plus paclitaxel was lower in this study than that reported previously for the combination (11.8 months).4 Additionally, recent trials using the combination of bevacizumab plus taxanes have produced survival endpoints similar to that demonstrated in the current study (median PFS, 9–10 months) and have not demonstrated OS benefits for the combinations compared with single-agent taxanes.5,6 Moreover efficacy results obtained with sunitinib plus paclitaxel in this study were comparable to those reported previously for this combination in a small exploratory study (median PFS, 7.6 months; ORR 39%).21

A second possible explanation of the efficacy results is that there may be an inherent inability of sunitinib to amplify or sustain the antitumor activity of paclitaxel beyond that produced by bevacizumab. Evidence providing some support for this hypothesis comes from the similar ORR of 32% in both arms, suggesting that sunitinib plus paclitaxel does induce tumor responses but not at a rate greater than that of bevacizumab plus paclitaxel, and the much shorter duration of response with sunitinib plus paclitaxel, indicating that this early activity could not be sustained.

A third possible explanation is that sunitinib may not be as active as the monoclonal antibody bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy, either because the inhibition of VEGF pathways is not as robust or because the additional targets of sunitinib (PDGFRs, KIT, RET, and others) may not be as relevant as originally predicted in producing an antitumor response in breast cancer. Indeed, results with another multitargeted VEGFR inhibitor, sorafenib, combined with chemotherapy have been mixed, although sorafenib has not been compared directly with bevacizumab. In a phase II study in advanced breast cancer, sorafenib in combination with paclitaxel did not yield a statistically significant improvement in PFS over the chemotherapy plus placebo,23 whereas in another study with a similar design, the combination of sorafenib plus capecitabine did yield a statistically significant improvement24 (although this latter result has yet to be evaluated under phase III conditions).

Last, when compared with bevacizumab in combination with weekly paclitaxel, sunitinib may induce toxicities that do not allow for prolonged treatment duration because of dosing interruptions and dose reductions. The safety profile exhibited by the combination of sunitinib plus paclitaxel in the current study overall was broadly comparable to that seen previously with either agent alone4,17,25 and consistent with that previously reported for the combination in the exploratory study.21 The most frequent treatment-related AEs with sunitinib plus paclitaxel included myelosuppressive events (neutropenia, anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia), gastrointestinal disorders (diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting), and constitutional disorders (fatigue and asthenia). Frequent nonhematologic AEs particular to paclitaxel included alopecia and peripheral neuropathy. However the frequency of grade 3/4 treatment-related neutropenia (52%) was particularly notable with sunitinib plus paclitaxel treatment. This level was much higher than that reported previously (as laboratory abnormality data) with single-agent sunitinib treatment of RCC or GIST (12% and 10%, respectively)26 or metastatic breast cancer (34%), noting that sunitinib was administered at 50 mg/day on schedule 4/2 in these studies. It was also higher than that reported for single-agent paclitaxel in metastatic breast cancer (0.3%-11%).4,27 A similarly high frequency (48%, reported as laboratory abnormalities) was however observed with the sunitinib-paclitaxel combination in the previously reported exploratory study,21 with the combined myelosuppressive effects of both agents cited as a possible explanation.

Importantly, the frequency and severity of treatment-related neutropenia reported with the sunitinib-paclitaxel combination in the current study was considerably higher than that seen with bevacizumab plus paclitaxel. Additionally, several other treatment-related AEs (diarrhea, nausea, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and hand-foot syndrome) were reported ≥ 10% more frequently in the sunitinib combination arm than in the bevacizumab combination arm, whereas only nail disorders were reported ≥ 10% more frequently in the bevacizumab combination arm. Therefore bevacizumab plus paclitaxel appeared to be more tolerable than sunitinib plus paclitaxel, although AEs in both treatment arms were generally manageable with standard medical therapy with or without dosing interruption and/or dose reductions.

The lower tolerability of the sunitinib-paclitaxel combination overall and the higher frequency and severity of neutropenia in particular was reflected in more dosing interruptions and dose reductions in the sunitinib combination arm (Table 2). Consequently the median relative dose intensity for sunitinib was 62% compared with 91% for bevacizumab. For paclitaxel the median total dose administered was almost 30% higher in the bevacizumab combination arm (1225 mg/m2) than in the sunitinib combination arm (944 mg/m2), and the median number of paclitaxel infusions was 15 and 11, respectively.

In the earlier exploratory study evaluating sunitinib plus paclitaxel,21 high-grade neutropenia was managed using short courses (3–4 days) of G-CSF based on modified National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines.28 The current study used those guidelines as a model without requiring a specific length of G-CSF treatment. Fifty-five percent of patients receiving sunitinib plus paclitaxel in the current study were given G-CSF. Those patients receiving G-CSF had a greater exposure to drug treatment as measured by days on treatment (median 14 vs. 7 paclitaxel infusions when receiving G-CSF vs. no G-CSF) and total paclitaxel dose administered (median 1102 vs. 630 mg/m2). On bevacizumab plus paclitaxel, patients receiving G-CSF also had greater exposure to paclitaxel but the difference was less pronounced (days on treatment, median 17 vs. 13 infusions; median total dose administered, 1414 vs. 1085 mg/m2). Overall the use of G-CSF was insufficient to improve the treatment effect in the sunitinib plus paclitaxel arm.

Conclusion

Statistical significance for superiority of efficacy of sunitinib plus paclitaxel compared with bevacizumab plus paclitaxel as first-line treatment for advanced breast cancer could not be established in this study. Moreover, bevacizumab plus paclitaxel was better tolerated than sunitinib plus paclitaxel. This was primarily due to a high frequency of grade 3/4 treatment-related neutropenia in the sunitinib-paclitaxel arm precluding delivery of the prescribed doses of both drugs. These findings demonstrate that the sunitinib plus weekly paclitaxel regimen evaluated in this study is clinically inferior to the bevacizumab plus paclitaxel regimen and is not a recommended treatment option for patients with advanced breast cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all of the participating patients and their families, as well as the network of investigators (who are listed in the appendix of this article), research nurses, study coordinators, and operations staff. The authors acknowledge María Luisa Mesa Becerril (i3 Research, Madrid, Spain), Jennifer L. Hoffman, Gertrude Luxana, and Maribeth H. Ryan (ExecuPharm, Inc., King of Prussia, PA), and Vatche Kalfayan (Pfizer Oncology, La Jolla, CA) for assistance in data collection. The study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc. Medical writing support was provided by Wendy Sacks at ACUMED (Tytherington, UK) and was funded by Pfizer Inc.

Dr. Robert and Dr. Minton received research funding from Pfizer, Inc. Dr. Gressot received research funding from Pfizer, Genentech, Amgen, Sanofi-Aventis, Johnson & Johnson, Millenium, and Onyx. Ms. Gernhardt, Dr. Huang, Ms. Liau, and Dr. Kern are or were Pfizer employees, and Ms. Gernhardt, Dr. Huang, and Ms. Liau own Pfizer stock.

Appendix

In addition to the authors, the following investigators participated in this study.

Germany—Mutterhaus der Borromaeerinnen, Trier: M.R. Clemens; Onkologischer Schwerpunkt am Oskar-Helene-Heim, Berlin: A. Kirsch; Universitaetsklinikum Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg: V. Mueller.

Italy—Ospedale Civico San Giovanni di Dio, Olbia: S. Ortu; Ospedale Misericordia, Grosseto: R. Algeri.

Spain—Centro Oncologico M.D. Anderson, Madrid: R. Colomer, J. Hornedo; Hospital de Cabueñes, Cabueñes: J.M. Gracia Marco, R.F. Martinez; Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañon, Madrid: P. Khosravi Shahi, G. Perez-Manga; Hospital Universitario de Guadalajara, Guadalajara: J. Cassinello.

United States—Advanced Medical Specialties, Miami, FL: L. Vila Jr; Annapolis Oncology Center, Annapolis, MD: J. Werner; Birmingham Hematology and Oncology Associates, Birmingham, AL: J.E. Cantrell Jr; Blue Ridge Medical Specialists, Bristol, TN: S.J. Prill; Bohannon, Cohen and Hufford MDs, San Francisco, CA: A.D. Baron; Bryan-LGH Hospital, Lincoln, NE: N.B. Green; Cancer and Blood Specialists of Nevada, Henderson, NV: J.A. Ellerton; Cancer Care Center, New Albany, IN: N. Mafooz Chowhan, M.S. Morkas; Cancer Care Centers of South Texas, San Antonio, TX: S.T. Wilks; Cancer Centers of Florida, PA, Ocoee, FL: C.A. Alemany; Carolina Oncology Specialists, Lenoir, NC: R.M. Orlowski; Center for Cancer Care & Research, Lakeland, FL: L.A. Franco; Central Indiana Cancer Centers, Indianapolis, IN: D.M. Loesch, M.M. Sgroi; Charleston Cancer Center, Charleston, SC: C.D. Graham; Citrus Hematology and Oncology Center, Inverness, FL: W.V. Harrer III; Clark Medical Plaza, Jeffersonville, IN: J.T. Hamm; Columbia Basin Hematology and Oncology PLLC, Kennewick, WA: T. Rado; Comprehensive Cancer Centers of Nevada, Henderson, NV: A. Thummala; Department of Pharmacy at Harbor Hospital, Baltimore, MD: Y.J. Lee; Duke University, Durham, NC: K.L. Blackwell; Eastern Carolina Internal Medicine, Pollocksville, NC: V.V. Abhyankar, R.E. Burgess; Florida Cancer Research Institute, Davie, FL: E. Del Prado Tan-chiu; Fremont Area Medical Center, Fremont, NE: M. Salman Haroon, Q.S. Khan; Gabrail Cancer Center, Canton, OH: N. Yousif Gabrail; Genesis Cancer Center, Hot Springs, AR: S. Garrel Divers; Guthrie Cancer Center, Corning, NY: E.T. O’Brien; Harrington Cancer Center, Amarillo, TX: B.T. Pruitt; Hematology Oncology Associates, Mooresville, IN: R.F. Manges; Hematology Oncology of the North Shore, Vernon Hills, IL: S.Ban; Hubert H. Humphrey Cancer Center, Robbinsdale, MN: T.G. Larson, G.G. Nagargoje; Ingalls Memorial Hospital, Harvey, IL: M.F. Kozloff; Jewish Hospital and St Mary’s Healthcare, Inc., Louisville, KY: J.B. Hargis; John B. Amos Cancer Center, Columbus, GA: A.W. Pippas; Kaiser Permanente Center, San Jose, CA: L. Fehren-bacher; Kaiser Permanente Northwest Region, Portland, OR: N. Tirumali; Kaiser Permanente SD Medical Offices, San Diego, CA: J.A. Polikoff; Kenansville Medical Center, Kenasville, NC: P.R. Watson; Kingsport Hematology and Oncology, Kingsport, TN: E.A. McElroy Jr; Lahey Clinic Medical Center, Burlington, MA: N. Natarajan; Longview Cancer Center, Longview, TX: R. Koteswararoa Koya, N. Sharma; Lynn Regional Cancer Center West, Boca Raton, FL: C.L. Vogel; Marion L. Shepard Cancer Center, Washington, NC: J. Robertson Crews; Maryland Oncology Hematology, Columbia, MD: E.J. Lee; Medical Oncology Associates of Wyoming Valley, Kingston, PA: B.H. Saidman; Memorial Cancer Institute, Hollywood, FL: A. Tobon Perez; Mercy Medical Center, Baltimore, MD: D.A. Riseberg; Missouri Cancer Associates, Columbia, MO: J.J. Muscato, D.M. Schlossman; Moses Lake Clinic, Moses Lake, WA: J.C. Smith; New Mexico Oncology, Albuquerque, NM: R.O. Giudice; Northern Utah Associates, Ogden, UT: V.L. Hansen; Northwest Cancer Specialists, PC, Portland, OR: D.A. Smith; Northwest Hospital Center, Randallstown, MD: C.I. Truica; Northwest Medical Specialties, Tacoma, WA: F.M. Senecal; Northwest Oncology and Hematology Associates, Coral Springs, FL: S. Weiss; Ocean Springs Hospital, Ocean Springs, MS: J. Clarkson; Office of Ronald Yanagihara, MD, Gilroy, CA: R.H. Yanagihara; Oregon Health & Science University Center for Health and Healing, Portland, OR: S. Yun-X Chui; Oncology/Hematology, Indianapolis, IN: M.A. Cooper; Osler Medical Inc./Osler Clinical Research, Melbourne, FL: S. Yandel; Penn State Hershey Cancer Institute, Hershey, PA: H.A. Harvey; Queens Hospital Center, Jamaica, NY: M.M. Kemeny; Raleigh Hematology Oncology Associates DBA, Raleigh, NC: W. Rosser Berry; Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY: T.L. O’Connor; Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL: R.D. Rao; Southeastern Medical Oncology Center, Goldsboro, NC: J.N. Atkins; Southern Cancer Center, Daphne, AL: J.R. George, P. Schwarzenberger; South Texas Institute of Cancer, Corpus Christi, TX: M.A. Ghraowi; Southwest Fort Worth Cancer Center, Fort Worth, TX: R.L. Ruxer Jr; St. Agnes HealthCare, Inc., Baltimore, MD: C. Brennan Miller; St. Luke’s Cancer Center, Allentown, PA: S. Satyanarain Agarwala; Texas Oncology Cancer Care and Research Center, Waco, TX: C.A. Encarnacion; Texas Oncology, PA, Bedford, TX: T.C. Anderson; Texas Oncology, PA, Dallas, TX: K.J. McIntyre; Texas Oncology, PA, Midland, TX: D.L. Watkins; Texas Oncology Sammons Cancer Center, Dallas, TX: J.L. Blum; The Angeles Clinic and Research Institute, Santa Monica, CA: S.A. Martino; University of California Davis Investigational Drug Services/Victoria Bradley Medical Center, Sacramento, CA: S.D. Christensen; University of New Mexico Cancer Center, Albuquerque, NM: M.E. Royce; USA Mitchell Cancer Institute, Mobile, AL: H.T. Khong; US Oncology Research and Clinical Pharmacy, Fort Worth, TX: J.R. Caton Jr, J.M. Davis, B.A. Hellerstedt, F.A. Holmes, D.L. Lindquist, D.A. Richards; Wake Forest University Health Sciences, Winston-Salem, NC: S.A. Melin; West Virginia University Hospital, Morgantown, WV: J. Abraham; Whittingham Cancer Center at Norwalk Hospital, Norwalk, CT: R.C. Frank; Winthrop Hospital, Mineola, NY: A.A. Hindenburg.

Footnotes

This work was presented in part at the 27th Annual Miami Breast Cancer Conference, March 3–6, 2010; Miami, FL.

Disclosures

All other authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Seidman AD, Tiersten A, Hudis C, et al. Phase II trial of paclitaxel by 3-hour infusion as initial and salvage chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2575–2581. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.10.2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seidman AD, Berry D, Cirrincione C, et al. Randomized phase III trial of weekly compared with every-3-weeks paclitaxel for metastatic breast cancer, with trastu-zumab for all HER-2 overexpressors and random assignment to trastuzumab or not in HER-2 nonoverexpressors: final results of Cancer and Leukemia Group B protocol 9840. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1642–1649. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.6699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology™ Breast cancer. 2009 V.I.2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller K, Wang M, Gralow J, et al. Paclitaxel plus bevacizumab versus paclitaxel alone for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2666–2676. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robert NJ, Dieras V, Glaspy J, et al. RIBBON-1: Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial of chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab for first-line treatment of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative, locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1252–1260. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.0982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miles DW, Chan A, Dirix LY, et al. Phase III study of bevacizumab plus docetaxel compared with placebo plus docetaxel for the first-line treatment of human epider- mal growth factor receptor 2-negative metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3239–3247. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.6457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pasanisi P, Venturelli E, Morelli D, et al. Serum insulin-like growth factor-I and platelet-derived growth factor as biomarkers of breast cancer prognosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:1719–1722. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paulsson J, Sjoblom T, Micke P, et al. Prognostic significance of stromal platelet-derived growth factor beta-receptor expression in human breast cancer. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:334–341. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.081030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bergers G, Song S, Meyer-Morse N, et al. Benefits of targeting both pericytes and endothelial cells in the tumor vasculature with kinase inhibitors. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1287–1295. doi: 10.1172/JCI17929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Potapova O, Laird AD, Nannini MA, et al. Contribution of individual targets to the antitumor efficacy of the multitargeted receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor SU11248. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1280–1289. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-03-0156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abrams TJ, Lee LB, Murray LJ, et al. SU11248 inhibits KIT and platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta in preclinical models of human small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:471–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim DW, Jo YS, Jung HS, et al. An orally administered multitarget tyrosine kinase inhibitor, SU11248, is a novel potent inhibitor of thyroid oncogenic RET/papillary thyroid cancer kinases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4070–4076. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mendel DB, Laird AD, Xin X, et al. In vivo antitumor activity of SU11248, a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor receptors: determination of a pharmacokinetic/pharmacody-namic relationship. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:327–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray LJ, Abrams TJ, Long KR, et al. SU11248 inhibits tumor growth and CSF-1R–dependent osteolysis in an experimental breast cancer bone metastasis model. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2003;20:757–766. doi: 10.1023/b:clin.0000006873.65590.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Farrell AM, Abrams TJ, Yuen HA, et al. SU11248is a novel FLT3 tyrosine kinase inhibitor with potent activity in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2003;101:3597–3605. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abrams TJ, Murray LJ, Pesenti E, et al. Preclinical evaluation of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor SU11248 as a single agent and in combination with “standard of care” therapeutic agents for the treatment of breast cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:1011–1021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burstein HJ, Elias AD, Rugo HS, et al. Phase II study of sunitinib malate, an oral multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with metastatic breast cancer previously treated with an anthracycline and a taxane. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1810–1816. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.5375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Escudier B, Roigas J, Gillessen S, et al. Phase II study of sunitinib administered in a continuous once-daily dosing regimen in patients with cytokine-refractory meta-static renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4068–4075. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barrios CH, Hernandez-Barajas D, Brown MP, et al. Phase II trial of continuous once-daily dosing of sunitinib as first-line treatment in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2009;7429(2 Suppl):7122. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26440. Abstract. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.George S, Blay JY, Casali PG, et al. Clinical evaluation of continuous daily dosing of sunitinib malate in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after imatinib failure. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:1959–1968. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kozloff M, Chuang E, Starr A, et al. An exploratory study of sunitinib plus paclitaxel as first-line treatment for patients with advanced breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1436–1441. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gradishar WJ, Kaklamani V, Prasad Sahoo T, et al. A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 2b study evaluating the efficacy and safety of sorafenib (SOR) in combination with paclitaxel (PAC) as a first-line therapy in patients (pts) with locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer (BC) Cancer Res. 2009;69(24 Suppl) Abstract 44. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baselga J Grupo Español de Estudio Tratamiento y Otras Estrategias Experimen-tales en Tumores Sólidos, Roché H, et al. A multinational double-blind, randomized phase 2b study evaluating the efficacy and safety of sorafenib compared to placebo when administered in combination with capecitabine in patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer (BC) Cancer Res. 2009;69(24 Suppl) (Abstract 45) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taxol® (paclitaxel) Injection [package insert] Princeton, NJ: Bristol-Myers Squibb; 2007. [accessed March12, 2011]. Available at http://www.bms.com/products/Pages/prescribing.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sutent (sunitinib malate) capsules, oral [package insert] New York, NY: Pfizer; 2010. [accessed March 12, 2011]. Available at http://www.pfizer.com/products/rx/rx_product_sutent.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albain KS, Nag SM, Calderillo-Ruiz G, et al. Gemcitabine plus paclitaxel versus paclitaxel monotherapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer and prior anthra-cycline treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3950–3957. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.9362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology™ myeloid growth factors. 2009 V.I.2010. [Google Scholar]