Abstract

Objectives

This study evaluated the effect of dentin pretreatment with collagen crosslinkers on matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) and cathepsin-K mediated (CK) collagen degradation.

Methods

Dentin beams (1×2×6 mm) were demineralized in 10% H3PO4 for 24h. After baseline measurements of dry mass, beams were divided into 11 groups (n=10/group) and, were pretreated for 5 min with 1% glutaraldehyde (GA); 5% GA; 1% grape-seed extract (GS); 5% GS; 10% sumac (S); 20μM curcumin (CR); 200μM CR; 0.l% riboflavin/UV (R); 0.5% R; 0.1% riboflavin-5-phosphate/UV (RP); and control (no pretreatment). After pretreatment, the beams were blot-dried and incubated in 1mL calcium and zinc-containing medium (CM, pH 7.2) at 37°C for 3, 7 or 14 days. After incubation, dry mass was reassessed and aliquots of the incubation media were analyzed for collagen C-telopeptides, ICTP and CTX using specific ELISA kits. Data were analyzed by repeated-measures ANOVA.

Results

The rate of dry mass loss was significantly different among test groups (p<0.05). The lowest 14 day mean dry mass loss was 6.98%±1.99 in the 200 μM curcumin group compared to control loss of dry mass at 32.59%±5.62, p<0.05, at 14 days. The ICTP release over the incubation period (ng/mg dry dentin) ranged between 1.8±0.51 to 31.8±1.8. Similarly, CTX release from demineralized beams pretreated with crosslinkers was significantly lower than CM (5.7±0.2 ng/mg dry dentin).

Significance

The results of this study indicate that collagen crosslinkers tested in this study are good inhibitors of cathepsin-K activity in dentin. However, their inhibitory effect on MMP activity was highly variable.

Keywords: gluteraldehyde, dentin, collagen crosslinker, matrix metalloproteinase, cysteine cathepsins

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Current dental adhesive techniques utilize acid-etching procedures or acidic monomers to create micromechanical retention for adhesive resin attachment to dentin. Dentin matrices contain proteolytic enzymes [1–3], the most recognized group being matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) that were developmentally secreted as inactive proenzymes. These proteases are uncovered and activated during the acid etching step in adhesive procedures [1,4]. In addition to MMPs, cysteine cathepsins were recently discovered in normal and carious dentin [5–8], increasing the list of potential endogenous proteases in dentin matrices.

Crosslinking agents have been reported to increase the stiffness of collagen by promoting additional hydrogen bonding and/or the formation of covalent inter- and -intra-molecular cross-links that prevents the long rod-like helical collagen molecules from sliding past each other under mechanical stress, and also reduce biodegradation by endogenous proteases [9–12]. Several synthetic (glutaraldehyde, carbodiimides etc.) and natural crosslinking (grape seed, cocoa, berries etc.) agents have been used for these purposes [9,10]. Gluteraldehyde has been used as a well-known crosslinking agent for the immobilization of proteins via the formation of a three-dimensional network as a result of intermolecular covalent crosslinking [13]. Concerns about cytotoxicity limit their use in many applications [14]. Natural polyphenols are capable of stabilizing collagen structure via the formation of multiple hydrogen bonds between collagen polypeptides [15]. Polyphenolic compounds of vegetable tannin present in fruits, nuts, vegetables, seeds, leaves and flowers, such as grape seed, sumac berries, or curcumin are crosslinking reagents that may decrease biodegradation of collagen, and do not have high cytotoxicity, compared to gluteraldehyde [9].

The use of collagen crosslinkers to improve the mechanical properties of demineralized dentin and to increase collagen crosslinks has been investigated extensively [11,12,16] and have been shown to increase the durability of resin-dentin bonding interfaces [17]. Long pretreatment times limit the clinical relevancy of these agents. However, Liu et al. [18,19] using demineralized dentin obtained excellent cross-linking with 15% proanthacyanidins in 60 sec. Additionally, a synthetic crosslinking agent, carbodiimide, was recently shown to inhibit protease activity [20] after an application time of 1 min.

Since there are a large variety of synthetic and natural crosslinkers available, a better understanding of the ability of these agents to interact with the endogenous protease activity in dentin matrix is of great interest. Thus, the aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of different collagen crosslinkers on their ability to inactivate dentin proteases. The null hypotheses tested were that pretreatment of demineralized dentin matrix with collagen crosslinkers does not inhibit dentinal MMPs or/dentinal cysteine K activity, and does not reduce the loss of dry mass of demineralized dentin matrix.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Specimen Preparation

One hundred-ten extracted non-carious human third molars from 18–21 year olds were obtained under a protocol approved by the Georgia Reagents University. The teeth were stored at 4 °C in 0.9% NaCl containing 0.02% NaN3 to prevent microbial growth, and were used within one month after extraction.

The enamel and superficial dentin of each tooth were removed with use of a low-speed saw (Isomet, Buehler Ltd., Lake Bluff, IL, USA) under water lubrication. Dentin beams with dimensions 6 × 2 × 1 mm were sectioned from the mid-coronal dentin (110 beams). Beams were completely demineralized in 10wt % H3PO4 for 24 h at 25°C and rinsed in distilled water at 4 °C for 1 h. Digital radiography was used to confirm the absence of residual minerals. Ten beams were assigned to each of 11 groups (N=10/group) so that the mean dry mass of each group was statistically similar. Six different crosslinkers (glutaraldehyde, GA; riboflavin/UVA, R; riboflavin-5-monophospate/UVA, RP; sumac berry extract, S; grape seed extract, GS; and curcumin, CR) were used at different concentrations (Table 1).

Table 1.

Synthetic and natural crosslinking agents used in this study.

| Abbreviation | Group | Solvent | Composition | Manufacturer | Lot No |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

GA1 GA5 |

1% Glutaraldehyde (v/v) 5% Glutaraldehyde (v/v) |

Distilled water | Protein crosslinker OHC(CH2)3CHO | Merck, Finland | S5334503-928 |

|

GS1 GS5 |

1% Grape seed extract (w/v) 5%Grape seed extract (w/v) |

Hot water | Vitis vinifera, Natural proanthocyanidin source | Mega-natural gold grape seed extract CA, USA | 13682503-01 |

|

R1 R5 |

0.1% Riboflavin (w/v) 0.5% Riboflavin (w/v) with UVA light 365nm, 7mW/cm2 |

Distilled water | Enzyme cofactor C17H20N4O6 | Sigma-Aldrich, Finland | OSOM1704Y |

| S | 10% Sumac (w/v) | Hot water | Natural proanthocyanidin source | Collected natural seed | |

| RP | 0.1% Riboflavin-5-phosphate (w/v) with UVA light 365nm, 7mW/cm2 | Distilled water | C17H20N4P | Sigma-Aldrich, Finland | 24887210 |

|

CR20 CR200 |

20μM Curcumin (w/v) 200μM Curcumin (w/v) |

0.2% ethanol in water | (1E,6E)-1,7-Bis(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-1,6-heptadiene-3,5-dione | LKT Laboratories Inc. | 458-37-7 |

The beams in each group were dipped in respective crosslinkers of the designated concentration for five minutes, and the riboflavin and riboflavin-5-phosphate groups were exposed to 365 nm UVA light at 7mW/cm2 for 5 min during the pretreatment. After pretreatment, the beams were blot-dried and then incubated into 1 mL calcium and zinc containing media (CM) in labeled screw-top polypropylene tubes at 37ºC for 3-, 7-, 14-day in a shaking-water bath (60 cycles/min). The CM contained 5 mM HEPES, 2.5 mM CaCl2.H2O, 0.02 mM ZnCl2, and 0.3 mM NaN3 (pH 7.2). The control group consisted of demineralized dentin beams without any crosslinker pretreatment.

2.2. Loss of Dry Mass

Loss of dry mass was used as an indirect measurement of hydrolysis and solubilization of the dentin matrix after each (3-, 7-, 14-day) incubation period [21]. Following demineralization, beams were transferred to individually labelled containers and placed in a vacuum desiccator containing dry silica beads for 72 h. The initial dry mass was measured with an analytical balance (XP6 Microbalance, Mettler Toledo, Hightstown, NJ, USA). After the dry mass measurement, beams were rehydrated for 1h in distilled water at 4ºC and placed in corresponding polypropylene tubes containing 1 mL complete media. After each incubation period, dentin beams were rinsed free of buffer salts in distilled water at 4ºC, followed by dehydration (72 h), measurement of mass loss and rehydration (1h) as previously described. The measurement of dry mass was repeated after each incubation period. After each incubation period the incubation medium was stored frozen (−80 ºC) until the end of the experiment when the media were analysed for ICTP/CTX.

2.3. Solubilized Telopeptides of Collagen

Matrix degradation by MMPs was determined by measuring the amount of solubilized type I collagen C-terminal cross-linked telopeptides (ICTP) [22] using an ICTP ELISA kit (UniQ EIA, Orion Diagnostica, Finland). After each incubation period, the incubation medium was replaced with fresh incubation medium. The only source of ICTP telopeptide fragments from collagen matrices is attributed to the telopeptidase activity of MMPs [22–24]. Matrix degradation by cathepsin K was determined by measuring the amount of solubilized C-terminal peptide, CTX in the incubation medium using the Serum CrossLaps ELISA (Immunodiagnostic System, Farmington, UK). The only known source of CTX is cathepsin K [23,25,26]. Although the optimum pH is 5.5, the release of CTX was done at pH 7.2. Preliminary work shows cathepsine K has about 10% as much activity in pH 7.2 as it does at pH 5.5. After each incubation period, the sealed tubes incubated in a shaker-water bath at 37°C were removed and the entire 1 mL of medium was removed. Ten to twenty μL aliquots of the incubation medium were used to measure solubilized ICTP and CTX collagen fragments.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

The percent loss of dry mass and the rate of release of ICTP (ng telopeptide/mg dry dentin/unit time) and CTX (ng telopeptide/mg dry dentin/unit time) from all groups were compared for normality (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) and homoscedasticity (modified Levine test). When the normality and equality variance assumptions of the data were valid, they were analyzed using repeated measures of ANOVA. When the data could not be transformed into a normal distribution, the data were analyzed with Kruskal Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. Post-hoc multiple comparisons were performed with the Tukey test using IBM SPSS v.21 (NY, USA). Statistical significance was preset at α = 0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Loss of Dry Mass

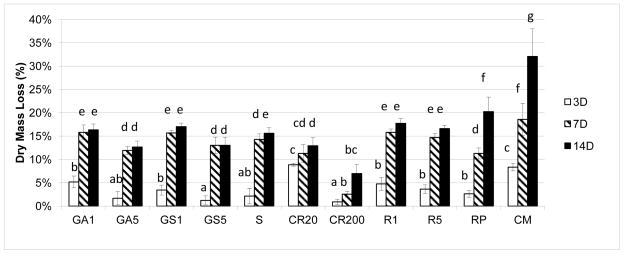

Loss of dry mass (Fig. 1) after 3, 7 and 14-day incubation periods showed a decrease in all experimental groups compared to the uninhibited control (p<0.05). Dentin beams pretreated with 200μM curcumin showed the least loss of dry mass of 0.9±0.5% at 3 days and 6.9 ± 1.9% loss at 14 days compared to the control loss of 8.4±0.8% at 3 days and 32±6% loss at 14 days (p<0.05). Among the crosslinker groups, increases in crosslinker concentration generally decreased the loss of dry mass with the exception of 0.1 vs 0.5% riboflavin, where the higher concentration did not inhibit loss of dry mass any more than the 0.1% concentration (Fig. 1). Riboflavin and riboflavin phosphate were good inhibitors of dry mass at 3 days but that inhibition was lost at 7 and 14 days. Grape seed and sumac extract behaved like riboflavin, giving good initial inhibitions at 3 days that were lost at 7 and 14 days (Fig. 1)

Figure 1.

Cumulative loss of dry mass from demineralized dentin beams pretreated with various crosslinkers after 3-, 7-, 14- days of incubation. The group incubated in calcium and zinc containing media (CM) without any crosslinker pretreatment served as the control (n=10). Groups identified by different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05). Abbreviations correspond to; glutaraldehyde (GA), grape-seed extract (GS), sumac (S), curcumin (CR), riboflavin/UV (R), riboflavin-5-phosphate/UV (RP) and no pretreatment control (CM).

3.2. Inactivation of total endogenous proteases of dentin

In the untreated controls, the rate of release of ICTP telopeptides was relatively high after 3 days, and increased significantly (p<0.05) after 7 days, and then fell to the 3 day level after 14 days (Fig 2). Similar to the mass loss results, the mean ICTP release of pretreatment groups showed significant differences (Fig. 2). The mean liberation of the most ICTP 32±1.28 ng/mg dry dentin per 7 days occurred in the control group, whereas groups pretreated with various crosslinkers liberated between 0.6±0.12 and 28.07±3.67 ng/mg dentin. Dentin matrices pretreated with 1 or 5 % grape seed, 10% sumac or 200 μM curcumin all showed significantly lower rates of ICTP telopeptide release at 3 days than 7 days, suggesting that crosslinker pretreatment was initially effective, but the inactivation was only temporary because, ICTP rate release rate increased significantly (p<0.05) after 7 day incubation. However, after 14 day incubation, the release rate fell significantly (p<0.05) in the 1% grape seed and sumac group, but still the 14 day release rate was about half as much as the 14 day ICTP release rate seen in controls.

Figure 2.

The rate of ICTP telopeptide release from demineralized dentin beams pretreated with various crosslinkers. The aliquots of the media were analyzed after 3-, 7-, 14- day of incubation. Values are ng telopeptide/mg dry dentin per unit time. Bar heights are mean values (n=10); brackets indicate ± SD. Abbreviations correspond to; glutaraldehyde (GA), grape-seed extract (GS), sumac (S), curcumin (CR), riboflavin/UV (R), riboflavin-5-phosphate/UV (RP) and no pretreatment control (CM).

Matrices pretreated with 0.1% or 0.5% riboflavin or 0.1% riboflavin phosphate showed no significant reduction in the rate of release of ICTP telopeptide fragments at any incubation periods with the exception of 7 day incubation for riboflavin-phosphate. The least release of ICTP telopeptides was seen in the specimens pretreated with 5% gluteraldehyde (GA5). In both GA groups there was no change in ICTP release between 1,2 and 14 days.

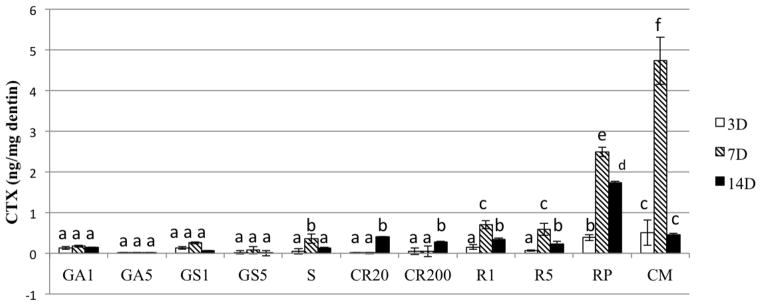

Unlike the variable rates of release of ICTP telopeptides by the experimental groups, the rate of release of CTX telopeptides by matrices treated with gluteraldehyde, grape seed, sumac and curcumin were all significantly less than the untreated controls (Fig. 3) and did not change very much over the experiment period. Unlike the inability of 0.1 and 0.5% riboflavin or 0.1% riboflavin phosphate to inhibit MMPs (i.e the release of ICTP telopeptides), the same pretreatment significantly (p<0.05) inhibited cathepsin K, although the day 3 inhibition was significantly more effective than the day 7 inhibition.

Figure 3.

The rate of release of CTX fragment of C-terminal telopeptide from demineralized dentin beams pretreated with various crosslinkers. The aliquots of the media were analyzed after each incubation period. Values are pg telopeptide/mg dentin. Bar heights are mean values (n =10); brackets indicate ± SD. Abbreviations correspond to; glutaraldehyde (GA), grape-seed extract (GS), sumac (S), curcumin (CR), riboflavin/UV (R), riboflavin-5-phosphate/UV (RP) and no pretreatment control (CM).

4. Discussion

The results of this study clearly show that the positive control, 5% gluteraldehyde, lowered the rate of release of both ICTP and CTX telopeptide fragments to a very low level, while treatment with polyphenols only temporarily inhibited ICTP release, although it permanently inhibited CTX release. The polyphenols and riboflavin/UV were much less effective against inhibiting ICTP release. Hence, the results require partial rejection of the first two null hypotheses. The third null hypothesis, that crosslinkers do not reduce the loss of dry mass is partially accepted. The crosslinkers reduced the loss of dry mass around 50%.

Loss of dry mass was used to quantitate total degradation of demineralized dentin matrix over time. The use of loss of dry mass as an indirect indication of the rate of solubilization of small peptides from insoluble collagen, assuming that there is an equilibrium between the rate of solubilization of, ICTP and CTX telopeptide fragments and their diffusion out of the insoluble collagen matrix that was partially cross-linked during pretreatment [27]. The recent work by Toroian et al. [28] and Takahashi et al. [29] on the size-exclusion characteristics of type I collagen show that small molecules (up to 6×103 Da) can diffuse in and out of collagen fibrils, but that molecules over 48×103 Da are excluded from entering or leaving insoluble type I collagen.

It is likely that pretreatment of insoluble dentin matrix by cross-linking agents would produce considerable additional intermolecular crosslinking, not only between adjacent collagen molecules but perhaps between ICTP and CTX telopeptides of collagen, lowering the permeability of ICTP and CTX fragments from dentin. As the concentration of ICTP or CTX increases in the cross-linked matrix, the diffusion gradient driving the diffusion of ICTP or CTX may increase to the point that they can diffuse into the incubation buffer. Such a mechanism might explain the sustained loss of dry mass from cross-linked matrices (Fig. 1).

Polyhydroxy crosslinkers, like grape seed extract, curcumin and sumac, are polyphenols that can hydrogen bond with the dentin. However, the results of this study show that hydrogen bonding may be reversible. Hydrogen bonds are weak intermolecular associations, which can be reversed by storage in buffer. Surprisingly, even the gluteraldehyde pretreated groups showed significant loss of dry mass after the 7 day incubation, compared to day 3, despite the covalent crosslinks by gluteraldehyde.

The ICTP release rate from the pretreated dentin groups was significantly lower over time compared to untreated controls, except for riboflavin groups which showed an increased ICTP release over time. As the ICTP release is due to MMP telopeptide activity [22], ICTP release provides information about the functional activity of endogenous dentin MMPs. When the concentration of grape seed polyphenols was increased, the ICTP release showed a significant decrease (p<0.05).

The ICTP release from dentin was previously shown to be 10-fold higher than the CTX release [30]. The major reason for this is when dentin matrices are incubated in pH 7.2 buffer, cathepsin-K must function more than 2 pH units from its optimum pH of 5.0 [31]. Cathepsin-K may play a crucial role in collagen degradation since it can cleave the helical portion of collagen at multiple sides, while MMP-8 can only cleave collagen at a specific gly-leu peptide bond [22].

The use of glutharaldehyde on demineralized dentin was previously shown to decrease the degradation in bovine dentin [16]. Although, glutharaldehyde is capable of creating covalent crosslinks in dentin collagen, its potential cytotoxicity limits its clinical use. The reduction in dry mass loss, and ICTP and CTX release obtained in the current study also confirm the efficiency of GA both for MMP and cathepsin-K mediated degradation. Even after a short 1 min pretreatment, these crosslinkers can inactivate these proteases by crosslinking their catalytic sites [13,32]. The ability of 5% gluteraldehyde to inhibit both ICTP and CTX telopeptide release indicates that it can inactivate most of the endogenous MMPs and cathepsin-K in dentin matrix. The inability of 5% gluteraldehyde to inhibit loss of dry mass more than 60 % suggests that the loss of dry mass may continue even after inactivation of the endogenous proteases of dentin. This might be due to the accumulation of collagen degradation products that continue to slowly leak out of demineralized dentin matrices long after the proteases are inactivated. Takahashi et al. [29] recently demonstrated that molecules of 10 KDa may have difficulty permeating into or out of collagen.

Cova et al. reported that UV crosslinking of collagen by riboflavin inactivated MMPs, particularly MMP-9 in the hybrid layer. They observed that 0.1% riboflavin treated specimens showed less nanoleakage, and inhibited the zymographic activity of dentin matrix MMPs [33]. However, the effectiveness of ribofilavin/UVA penetration is limited to 200 μm [34]. The results of the current study using 1.0 mm thick demineralized beams, showed that riboflavin/UVA treatment produced almost no MMP inhibition since the ICTP release in that group was similar to that of the control group. Furthermore, the CTX release from matrices treated with riboflavin-5-phosphate/UVA was the highest among pretreatment groups. This might be due to the fact that, riboflavin/UVA and riboflavin-5-phosphate/UVA could only affect the superficial dentin matrix, and that UV light penetration may not be effective deeper than 200 μm. The riboflavin that was not crosslinked by UVA might leach out over time, restoring protease activity over time.

In the control group, the release rate of both ICTP and CTX telopeptide fragments was highest at 7 days and then fell significantly at 14 days (P<0.05). It is interesting to speculate that matrix-bound proteases may have a limited degradation zone that is restricted to the zone around the tethered enzymes. In such a model, the proteases would hydrolyze peptides within their immediate environment, causing the release of telopeptide fragments to decrease over time. The loss of dry mass shows the same time-dependent behavior when it is expressed as percent per day (results now shown). However, it is possible for matrix-bound proteases to temporarily become unbound if they destroy the peptides to which they are bound, but then re-attach to the nearest binding site.

If we consider the total telopeptide fragment release of (ICTP+CTX fragments) over time (results not shown), the lowest release of total telopeptides was obtained in dentin beams treated with 5% GA, indicating that it inactivated almost most of the matrix MMP and cathepsin K, irreversibly. The 5% GA group indicates that 5 min pretreatment is adequate time for crosslinks to diffuse throughout the dentin matrices. The highest release of telopeptide fragments was seen in the uninhibited controls. The next highest release was seen in the riboflavin/UVA and riboflavin phosphate/UVA groups, indicating that they were not nearly as effective as the polyphenols or gluteraldehyde. Longer incubations where the incubation medium is replaced weekly should determine how much the polyphenol inhibition of protease activity can be reversed over time.

The result of this study indicated that polyphenols are better inhibitors of cathepsin K activity than the larger MMPs in dentin. The reason for this is unknown at this time. The results of this work require partial rejection of the null hypothesis, that the use of crosslinkers does not inactivate dentin proteases.

Highlights.

Dentin matrices contain proteolytic enzymes which are uncovered and activated during the acid etching step in adhesive procedures

For the first time, we evaluated the inhibition effect of collagen crosslinkers on both the MMP-mediated and Cathepsin-K mediated degradation separately

Collagen crosslinkers as a new class of protease inhibitors holds much promise for increasing the durability of resin-dentin bonds and saving billions of dollars of dental care currently spent on replacement of resin composites.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant #8126472 from the Academy of Finland to AT-M (PI), EVO funding of Turku University Hospital to AT-M (PI) and by R01 DE015306 from the NIDCR to DHP, P.I. Prof. Pashley is a Hi-Sci scholar for the King Abdulazziz Faculty of Dentistry, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Footnotes

The authors do not have a financial interest in products, equipment, and companies cited in the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mazzoni A, Pashley DH, Nishitani Y, Breschi L, Manello F, Tjäderhane L, Toledano M, et al. Reactivation of inactivated endogenous proteolytic activities in phosphoric acid-etched dentin by etch-and-rinse adhesives. Biomater. 2006;27:4470–4476. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sulkala M, Tervahartiala T, Sorsa T, Tjäderhane L. Matrix metalloproteinase 8 (MMP-8) is the major collagenase in human dentin. Arch Oral Biol. 2007;52:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tjäderhane L, Nascimento FD, Breschi L, Mazzoni A, Tersariol IL, Geraldeli S, Tezvergil-Mutluay A, et al. Optimizing dentin bond durability: control of collagen degradation by matrix metalloproteinases and cysteine cathepsins. Dent Mater. 2013;29(1):116–135. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pashley DH, Tay FR, Yiu C, Hashimoto M, Breschi L, Carvalho RM, Ito S. Collagen degradation by host-derived enzymes during aging. J Dent Res. 2004;83(3):216–221. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tersariol IL, Geraldeli S, Minciotti CL, Nascimento FD, Pääkkönen V, Martins MT, Carrilho MR, et al. Cysteine cathepsins in human dentin pulp complex. J Endod. 2010;36:475–481. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nascimento FD, Minciotti CL, Geraldeli S, Carrilho MR, Pashley DH, Tay FR, Nader HB, et al. Cysteine cathepsins in human carious dentin. J Dent Res. 2011;90:506–511. doi: 10.1177/0022034510391906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scaffa PM, Vidal CM, Barros N, Gesteira TF, Carmona AK, Breschi L, Pashley DH, et al. Chlorhexidine inhibits the activity of dentin cysteine cathepsins. J Dent Res. 2012;91:420–425. doi: 10.1177/0022034511435329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vidal CMP, Tjäderhane L, Scaffa PM, Tersariol IL, Pashley D, Nader HB, Nascimento FD, et al. Abundance of MMPs and cysteine cathepsins in caries-affected dentin. J Dent Res. 2014;93(3):269–274. doi: 10.1177/0022034513516979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han B, Jaurequi J, Tang BW, Nimni ME. Proanthocyanidin: A natural crosslinking reagent for stabilizing collagen matrices. J Biomed Mater Res. 2003;65A:118–124. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sung HS, Chang WH, Ma CY, Lee MH. Cross-linking of biological tissues using genipin and/or carbodiimide. J Biomed Mater Res. 2003;64A:427–438. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bedran-Russo AK, Pereira PN, Duarte WR, Drummond JL, Yamauchi M. Application of crosslinkers to dentin collagen enhances the ultimate tensile strength. J Biomed Mater Res B: Appl Biomater. 2007;80:268–272. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bedran-Russo AK, Castellan CS, Shionara MS, Hassen L, Antunes A. characterization of biomodified dentin matrices for potential preventive and reparative therapies. Acta Biomaterialia. 2011;7:1735–1741. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Migneault I, Dartiguenave C, Bertrand MJ, Waldron KC. Glutaraldehyde: behavior in aqueous solution, reaction with proteins, and application to enzyme crosslinking. BioTechniques. 2004;37:790–802. doi: 10.2144/04375RV01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill SD, Berry CW, Seale NS, Kaga M. Comparison of antimicrobial and cytotoxic effects of glutaraldehyde and formocresol. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1991;71:89–95. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(91)90530-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tu ST, Lollar RM. A concept of the mechanism of tannage by phenolic substances. J Am Leather Chem Ass. 1950;45:324–346. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ritter AV, Swift EJ, Jr, Yamauchi M. Effects of phosphoric acid and glutaraldehyde-HEMA on dentin collagen. Eur J Oral Sci. 2001;109:348–353. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2001.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Ammar A, Drummond JL, Bedran-Russo AK. The use of collagen cross-linking agents to enhance dentin bond strength. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2009;91(1):419–24. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y, Wang Y. Effect of proanthocyanidins and photo-initiators on photo-polymerization of a dental adhesive. J Dent. 2012;41:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y, Dusevich V, Wong Y. Proanthocyanidins rapidly stabilize the demineralized dentin layer. J Dent Res. 2013;92:746–752. doi: 10.1177/0022034513492769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tezvergil-Mutluay A, Mutluay MM, Agee KA, Seseogullari-Dirihan R, Hoshika T, Cadenaro M, Breschi L, et al. Carbodiimide cross-linking inactivates soluble and matrix-bound MMPs, in vitro. J Dent Res. 2012;91:192–196. doi: 10.1177/0022034511427705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carrilho MRO, Tay FR, Donnelly AM, Agee KA, Tjaderhäne L, Mazzoni A, Breschi L, et al. Host-derived loss of dentin stiffness asoociated with solubilization of collagen. J Biomed Mater Res B, Appl Biomater. 2009;90B:373–380. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garnero P, Ferreras M, Karsdal MA, Nicamhlaoibh R, Risteli J, Borel O, Qwist P, et al. The type I collagen fragments ICTP and CTX reveal distinct enzymatic pathways of bone collagen degradation. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:859–867. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.5.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garnero P, Borel O, Byrjalsen I, Ferreras M, Drake FH, McQueney MS, Foged NT, et al. The collagenolytic activity of cathepsin K is unique among mammalian proteinases. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32347–32352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.32347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osorio R, Yamauti M, Osorio E, Ruiz-Requena ME, Pashley DH, Tay FR, Toledano M. Effect of dentin etching and chlorhexidine application on metalloprotease-mediated collagen degradation. Eur J Oral Sci. 2011;119:79–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2010.00789.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karsdal MA, Woodwoth T, Henriksen K, Maksymowych W, Genant H, Vernand P, Christiansen C, et al. Biochemical markers of ongoing joint damage in rheumatoid artritis-current and future applications, limitation and opportunities. Arthritis Res & Therapy. 2011;13:215–233. doi: 10.1186/ar3280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tezvergil-Mutluay A, Agee K, Mazzoni A, Carvalho RM, Carrilho M, Tersariol IL, Nascimento FD, et al. Can quaternary ammonium methacrylates inhibit matrix MMPs and cathepsins. Dent Mater. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2014.10.006. pii: S0109-5641(14)00639-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bronstein P. Covalent cross-links in collagen: a personal account of their discovery. Matrix Biol. 2003;22:385–391. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(03)00061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toroian D, Lim JE, Price PA. The size exclusion characteristics of type I collagen: implications for the role of noncollagenous bone constituents in mineralization. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:22437–22447. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700591200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takahashi M, Nakajima T, Tagami J, Scheffel DLS, Carvalho RM, Mazzoni A, Cadenaro M, et al. The size-exclusion characteristics of type I collagen in dentin matrices. Acta Biomaterialia. 2013;9:9522–9528. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tezvergil-Mutluay A, Mutluay M, Seseogullari-Dirihan R, Agee KA, Key WO, Scheffel DLS, Breschi L, et al. Effect of phosphoric acid on the degradation of human dentin matrix. J Dent Res. 2013;92(1):87–91. doi: 10.1177/0022034512466264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kometani M, Nonomura K, Tomoo T, Niwa S. Hurdles in the drug discovery of cathepsin K inhibitors. Curr Top Med Chem. 2010;10(7):733–744. doi: 10.2174/156802610791113478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Isenburg JC, Simionescu DT, Vyavahare NR. Elastin stabilization in cardiovascular implants: improved resistance to enzymatic degradation by treatment with tannic acid. Biomater. 2004;25(16):3293–33302. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cova A, Breschi L, Nato F, Ruggeri AJ, Carrilho M, Tjäderhane L, Prati C, et al. Effect of UVA-activated riboflavin on dentin bonding. J Dent Res. 2011;90(12):1439–1445. doi: 10.1177/0022034511423397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ashwin PT, McDonnell PJ. Collagen cross-linkage: a comprehensive review and directions for future research. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94:965–970. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.164228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]