Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Key Words: Gorham-Stout Disease, generalized lymphatic anomaly, lymphatic malformation, treatment, management, sunitinib, taxol, metronomic chemotherapy, lymphangiogenesis, chylothorax

Abstract

The recently revised ISSVA classification approved in Melbourne in April 2014 recognizes generalized lymphatic anomaly and lymphatic malformation in Gorham-Stout disease. The 2 entities can overlap in presentation, as both are characterized by destructive lymphatic vessel invasion of the axial skeleton and surrounding soft tissues. At least at present, no standard therapeutic options exist, and due to the rarity of the disease, no clinical trials are available. We present 2 patients, 1 with generalized lymphatic anomaly and 1 with lymphatic malformation in Gorham-Stout disease, with severe exacerbation during puberty. The first child presented in florid pulmonary failure and pleural effusion, the other with severe pain due to bone destruction of the pelvis and inability to walk. Both were treated using individualized protocols. The manuscript describes the rationale for choosing sunitinib in combination with low-dose (metronomic) taxol. Both patients experienced clinical and radiologic response without major toxicities, suggesting that patients with rare conditions may benefit from individualized, molecularly based therapies.

This manuscript presents 2 types of systemic lymphatic malformations described in the recently revised ISSVA classification approved in Melbourne in April 2014.1 Generalized lymphatic anomaly (GLA) is characterized by multifocal lymphatic malformation affecting the skin and superficial soft tissues, viscera of the abdominal and thoracic cavities, and bone. The bone disease in GLA usually spares the bone cortex, and does not progress with time. GLA can present with acute or persistent pericardial, pleural, or peritoneal effusions. Although the lymphatic malformation in Gorham-Stout disease (GSD) is also characterized by lymphatic malformation affecting a single or multiple bones and adjacent soft tissues, the osteolysis is progressive and invades the bone cortex. It was originally described in the orthopedic literature as disappearing or vanishing bone disease.2–4 The progression of GSD often includes visceral progression with thoracic and abdominal involvement leading to effusions and ascites. Pathologic fractures occur in both GLA and GSD, even though they are more frequent in GSD.

The older literature can be confusing as clinicians often describe involvement of soft tissues and visceral organs by lymphatics as “congenital lymphangiomatosis,” “disseminated lymphangiomatosis,” or “multifocal lymphangiomatosis.” These terms are better to be avoided because they are not very helpful for prognostication or in guiding future medical management.

In addition to the skeleton, systemic lymphatic disease often includes aggressive unremitting proliferation of lymphatic vessels in lungs, spleen, and other visceral organs.5–7 This aggressive disease benefits from early intervention. In contrast, many patients with GLA can be safely observed, and timely management depends on correct diagnosis. At least at present, there are no molecular markers or radiologic features that can identify the patient at risk for progression. Some clinicians feel that multiple lesions with distinct sclerotic edges may suggest disease that will remain stable for years, and that the presence of a soft tissue component and/or pleural effusion may identify disease more likely to progress,7 but even for experts, defining an incipient progression is difficult.

Notable are also the differences in the character of the disease across the life span. Commonly, a previously quiescent disease is exacerbated by puberty,8,9 suggesting an anabolic effect of sex-specific steroids on the lymphatic vasculature. Although in early childhood most GLA/GSD diagnoses are incidental findings of a lytic lesion during a trauma evaluation, the diagnoses of GSD/GLA during puberty/adolescence are usually due to symptoms associated with disease progression.9,10

For those pediatricians working without the help of a vascular anomalies expert, it is often difficult to recognize an acute exacerbation of systemic lymphatic lesions such as GLA/GSD and recommend the most appropriate early intervention. GLA, because of its resemblance to metastatic lesions is often referred to oncology, whereas GSD is usually evaluated by orthopedics. The referral to a vascular anomalies center is often delayed and the window of opportunity is often missed until the disease gathers an unremitting course, involving multiple organs leading eventual cardiovascular collapse. Even though there are no standard therapies for GLA, early case reports indicate that stabilization of the disease and/or remission can be achieved. As is the case with many rare diseases, a large spectrum of interventions has been used and includes: glucocorticoids, radiation, bisphosphonates, combination of radiation and bisphosphonates, pegylated-interferon, regular interferon and heparin, bevacizumab, or thalidomide.

The treatment varies widely. A retrospective analysis of 67 cases (64 published in Chinese and 3 in English) from 54 publications were analyzed,11 and the treatment varied from surgery (n=27, 40.3%), radiation therapy (n=6, 9.0%), surgery combined with radiation therapy (n=2, 3.0%), and medical therapy (n=7, 10.4%), such as interferon (n=2), bisphosphonates (n=1), calcium/vitamin D (n=1), cyclophosphamide/5FU (n=2), and calcitonin/alendronate (n=1). The few available larger case series10,12 also included cases before the emergence of molecular markers and the efficacy of the used oncological therapies could not be assessed. Recently, a successful use of bevacizumab, an antibody against vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), in a Gorham-Stout disease patient was reported.13

As oncology embraces molecularly based therapeutics, many promising antiangiogenic agents and combinations that may be useful in GLA/GSD are being accepted, and sharing these strategies is extremely important. In absence of evidence-based, disease-modifying, curative therapy for GLA/GSD, this manuscript provides a rational approach to individualizing the treatments of patients with GLA/GSD on the basis known biology, and their tissue-specific molecular markers. We used a synergistic combination of sunitinib, a direct inhibitor of angiogenesis, and low-dose metronomic schedule14 of taxol to minimize toxicity in this nonmalignant disease.

CASE REPORTS

The patients and their guardians were informed of the risks, benefits, and therapeutic alternatives before treatment on an individualized protocol. It was stressed that their lesions were not amenable to more standard therapeutic approaches such as surgery or sclerotherapy, and they understood that the goal of the therapy was disease stabilization rather than cure.

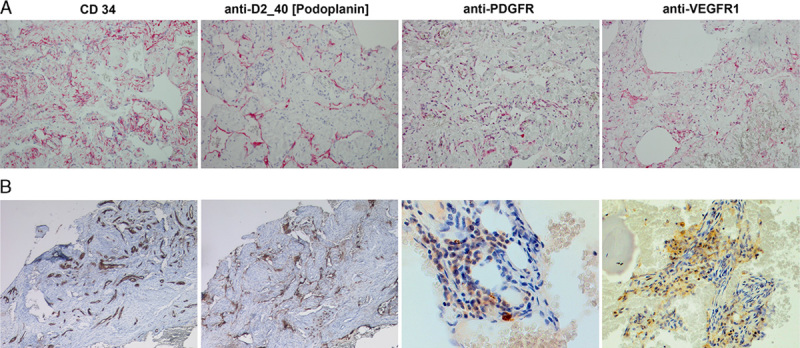

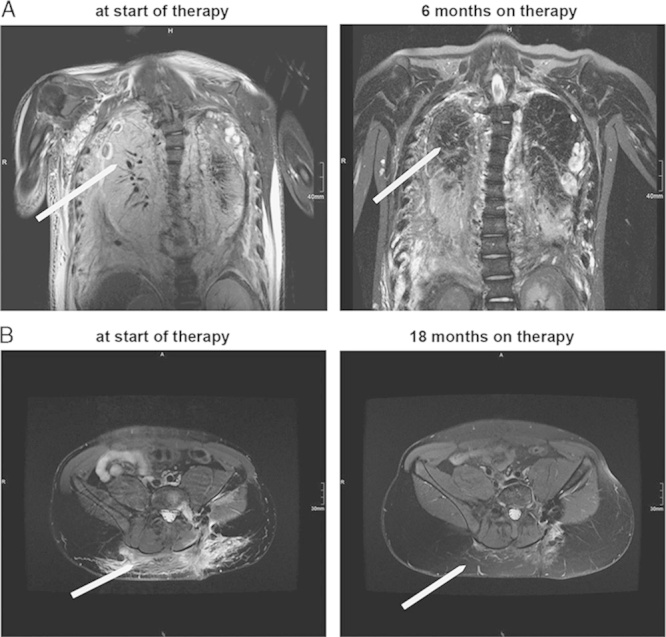

The first patient was initially diagnosed with GLA at the age of 7 years. He presented with recurrent coughing leading to the diagnosis of a left-sided chylothorax requiring multiple drains. The effusion did not recede despite a medium chain triglyceride (MCT) diet. The child’s pulmonary disease was exacerbated as he entered puberty. By 13 years, he had severe pulmonary insufficiency, and large persistent bilateral chylous pleural effusions due to the presence of bilateral paravertebral lymphatic malformation extending from third to seventh thoracic vertebrae. He had undergone external drainage of the pleural effusion followed by pleurodesis, with minimal improvement in symptoms. Immunohistochemistry of this pleural biopsy showed D2-40 and CD31+ endothelium with expression of PDGFR and VEGFR1 (Fig. 1). At the time of this child’s diagnosis, there was no clinically applicable antibody for VEGFR2, but there was sufficient overlap between VEGFR1 and 2 and 3 using the ZYTOMED Systems (GmbH, Berlin) antibody to justify its use. The choice of PDGFR was based on previously published data on its expression in Gorham disease.15 The child ultimately required tracheostomy for long-term airway management, and a gastroduodenostomy to facilitate low fat, MCT diet. It was at this late point of the disease progression that he was referred to the oncologist. He was initially treated with sarcoma-like therapy with 2 cycles of cyclophosphamide (1500 mg/m2) and vincristine (1.5 mg/m2). Despite severe side effects such as neutropenia, sepsis, and candidiasis, this regimen provided no benefit. After 2 months on mechanical ventilation, and no standard therapeutic options, we reviewed the tissue markers with hope to develop new approaches for this child. Although it is not always possible to do colocalization studies to establish that lymphatic endothelium is positive for tyrosine kinase receptors such as VEGFR and PDGFR in clinical setting, the pleural biopsy showed D2-40+ and CD31+ endothelium, with PDGFR+ and VEGFR-1/2+ expression in the same vascular pattern (Fig. 1) providing some reassurance about the histologic configuration. The goals of the therapy, namely disease stabilization and extubation, were clearly identified to parents, and consents obtained before initiation of treatment. The child’s therapy was then changed to sunitinib 12.5 mg daily and taxol 10 mg/m2/once weekly. The dose of taxol was increased every 4 weeks up to 60 mg/m2/once weekly, and was tittered to avoid myelosuppression. There were no significant toxicities with this regimen, no peripheral neuropathy, no neutropenia, and no increase in infections. Over the subsequent 12 months, he was weaned off mechanical ventilation, extubated, and weaned from 8 to 10 L of O2 to room air (supplemental data, Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JPHO/A111). He had both clinical and radiologic regression of the pulmonary infiltration, as well as of the soft tissue lesions (Fig. 2). Unfortunately, the patient later relapsed on therapy, required reintubation, and ultimately succumbed to the disease.

FIGURE 1.

Immunhistochemistry of pleural biopsy in case 1 (A), and of left ileosacral soft tissue in case 2 (B). Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded archival tissues were processed using standard IHC methods and stained with anti-VEGFR-1, anti-PDGFR, and anti-podoplanin (D2-40) antibodies (all from ZYTOMED Systems; GmbH) at 1:20 dilution. In both cases the CD34+ endothelium was also positive for D2-40 confirming its lymphatic origin. Further support for the therapy was the positive staining for PDGFR and VEGFR-1 tyrosine kinases, both targets of sunitinib. All images were taken at ×20 magnification with the exception of PDGFR and VEGFR in case B (ileosacral soft tissue), which was captured with ×40 lens. VEGFR indicates vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

FIGURE 2.

Radiologic findings. For both patients T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging at baseline (before initiation of therapy), at 6 and 18 months on therapy. In both, the thorax images for case 1 (A), and the pelvis images in case 2 (B) there is a marked reduction of the pathologic lymphatic tissue burden, as well as of the accompanying edema.

The second patient was diagnosed with GSD at the age of 14 years, after an episode of severe pain and swelling in the lower back after a football injury. The magnetic resonance imaging revealed a diffuse osteolytic lesion in the left ileosacral articulation, ileum, and sacrum, as well as in several vertebral bodies. The difficulty with histologic diagnosis necessitated 3 consecutive biopsies, leading to a recalcitrant lymphatic leak for over 3 weeks. This child also received MCT diet. The ileosacral articulation was stabilized by a supportive corset, which also provided some degree of vascular compression. As the lesion continued to progress, the decision was made to escalate therapy, but no standard therapeutic options were available. We again discussed with parents and clearly identified the goal of the potential targeted therapy, namely disease stabilization. We summarized this in a consent that included the risk, benefits, and goals of the various therapies used in the past. We then initiated a combination therapy with sunitinib 12.5 mg PO daily and intravenous taxol 10 mg/m2/once weekly. The child completed 12 months of therapy, and experienced gradual improvement in both clinical and radiologic measures (Fig. 2). There were no significant toxicities with this regimen, no peripheral neuropathy, no neutropenia, and no increase in infections. The therapy was stopped after a year, and he has remained stable for over 4 years.

DISCUSSION

The classification of lymphatic lesions has recently been updated.1 By this new ISSVA classification, case 1 carries the diagnosis of “GLA” because pulmonary effusion was the first pathologic finding, and the second case with a large aggressively osteolytic lesion in the sacrum is a “lymphatic malformation in Gorham-Stout disease.” The purpose of this manuscript is to introduce new therapeutic options for GLA/GSD rather than review classification, and we refer the reader to recent publications discussing the differences between the 2 entities.7 Whether one views GSD/GLA as a continuum ranging from a single lymphatic malformation of the bone (monostotic), multiple but nonprogressive lytic lesions of the bone (polyostotic), to disseminated lymphangiomatosis with pulmonary compromise,6,16 the diagnostic distinction is important for management. Recognizing which lesion is likely to progress is more likely to lead to a timely referral to an experienced multidisciplinary team familiar with the disorder, and to institution of a timely and effective therapy.

The etiology of GLA/GSD remains unclear, even though the triggering effect of inflammation, puberty, and trauma is quite established. There are early indications that at least some of these osteolytic bone lesions are due to genetic mutations.17 The V-MAF—musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene family protein B was described in 11 cases of multicentric carpotarsal osteolysis syndrome by the Australian group of Zankl and Duncan,18 the lymphoedema-distichiasis syndrome described in 74 patients with FOXC2 mutation,19 the Nonne-Milroy syndrome in patients with FLT4/VEGFR3 mutation,20 hypotrichosis-lymphedema-telangiectasia in patients with SOX18,21,22 and primary GLA (Hennekam lymphangiectasia-lymphedema syndrome) in patients with CCBE1 mutation.23 It is very likely that with time additional genetic mutations will further clarify the spectrum of lymphatic malformations of the bone. Although the genetic alterations may be both germinal and/or somatic, neither GLA nor GSD are presently associated with a risk of malignant transformation.7

The pathogenesis of GLA/GSD is also unclear. Although some investigators believe that there is minimal cell turnover in the pathologic lesions of GLA or GSD, the disease is in fact characterized by an active proliferation of lymphatic endothelium,24 by platelet derived growth factor pathway activation,15 and by upregulation of a number of lymphangiogenesis stimulating pathways.5 A recent analysis of the cellular and humoral mechanisms underlying GSD25 compared the numbers and sensitivity to osteoclastogenic factors between age/sex-matched controls and a GSD patient. They found that even though the number of circulating osteoclast progenitors was not increased, the osteoclast precursors showed an increased sensitivity to IL-1β, IL-6/sIL-6R, and TNFα, leading to increased osteoclastic activity.

It is unclear whether the lymphatic vessel proliferation in GLA/GSD is a secondary or a primary event. Although physiologically normal, healthy lymphatic endothelium serves to decompress tissues by returning lymphatic fluid to venous circulation, its pathologic counterpart looses this directional flow and transforms into a leaky, invasive, and proliferative vascular meshwork. These types of leaky lymphatic endothelial cells have been well described in other lesions with pathologic lymphangiogenesis such as in Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome and kaposiform lymphangiomatosis, as well as in many malignancies. The invasive nature and bone destruction within these lesions can be surmised from the increased acid phosphatase activity in mononuclear phagocytes, multinuclear osteoclasts, and vascular endothelium.26 Furthermore, because lymphatic vessels are not present in healthy intact bones,27 lesions in both GLA and GSD are likely to represent a manifestation of systemic disease with either primary or secondary bone and soft tissue activation. In either way, activated lymphatic endothelium can be inhibited by a combination of metronomic therapy and antiangiogenic agent.14 The inhibition of activated stroma using this approach may be further amplified by inhibition of alternative pathways such as the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway by sirolimus. The efficacy of sirolimus in complex vascular anomalies such as kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and diffuse microcystic lymphangiogenesis has recently been published,28 but its efficacy had not been established at the time we needed intervention for our 2 patients. It should be pointed out here that the inhibition of the ras/raf/MAPK pathway by sunitinib had equivalent outcome to the inhibition of PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway (extubation and stabilization of disease), suggesting that these 2 pathways are alternatives and inhibition of both would have synergistic effect.

The lack of understanding of the etiology and pathogenesis of GLA/GSD has been the biggest hindrance in developing effective therapeutic approaches. Although gene therapy may be possible one day for those sybtypes of systemic lymphatic malformations where a single genetic defect has been identified single gene mutations, many GLA/GSD patients will need therapy before then. Because both GLA and GSD are difficult to treat by surgery alone, systemic therapies need to be directed to minimizing the process of lymphangiogenesis, stromal invasion, and at maximizing bone restoration. Even though these lesions are not cancers, or even tumors, they grow and progress. Thus, even though they have not been historically thought to be proliferative, and are therefore presumed not to respond to traditional high-dose chemotherapy, they do grow and proliferate24 and are highly dependent on growth factors15 and can therefore be treated with biological agents. Because the target of metronomic chemotherapy is the tumor stroma rather than the cancer cell, the combination of low-dose metronomic chemotherapy and a direct angiogenesis inhibitor provides a good, minimally toxic therapeutic alternative for lymphatic malformations. The strategy has shown efficacy in preclinical and clinical settings.29 The rationale of using this particular combination of a tubulin inhibitor and direct anti-angiogenic agent was supported by the extreme sensitivity of endothelial cells (both lymphatic and microvascular) to tubulin inhibitors,30 and on the presence of increased levels of PDGFR and VEGFR1/2 in the patient tissues (Fig. 1). Unlike tumor cells, endothelial cells rely on cytoskeleton for both adhesion and polarization, and cannot grow in anchorage independent manner. Endothelial cells are also exquisitely dependent on continuous supply of growth factors and the combination of a direct angiogenesis inhibitor with low-dose tubulin inhibitor has been shown to lead to vascular collapse.14 The combination is particularly attractive in cases of histologically benign, but aggressively invasive disease such as GLA, because a long-term minimally toxic treatment is usually needed and because the likelihood of causing secondary malignancies with this regimen is extremely low.

The radiologic and clinical responses observed in the 2 patients presented in this manuscript support the applicability of this approach in GLA and severe progressive GSD. In our first case, an argument can be made that an earlier application of this therapeutic combination may have prevented the end-organ damage resulting from a long-standing pathologic lymphatic infiltration of pulmonary vasculature. He was diagnosed at 7 years of age, and as expected, his disease was exacerbated by puberty leading to irreversible respiratory compromise. Despite the chronicity of the pulmonary disease, he experienced a marked radiologic and clinical improvement on the combination regimen. It should also be noted that he required long-term therapy. Because long-term anti-angiogenic therapy has been shown to lead to tolerance,31 one is left to wonder if a drug holiday, or a change to an alternative regimen may have resulted in a better outcome for this child. Even though the damage caused by many years of chronic disease would not have been reversed, it is possible that a long-term quiescence may have ensued with changing the regimen.

Both of the cases presented in this manuscript showed with disease exacerbation during puberty. Although many experts in the vascular anomalies field have made this observation, there is paucity of studies on the topic. The frequency of disease exacerbation during puberty, pregnancy, and other conditions involving hormonally unstable states is consistent with the preclinical evidence of testosterone and estrogen having anabolic effect on the vasculature.32 The second inciting stimulus often observed in clinic is trauma. In the case of the second child, the inflammation accompanying an acute injury may have contributed to an exacerbation of otherwise quiescent disease. The inflammation associated with injury tends to disturb the balance of stimulators and inhibitors of lymphangiogenesis and can lead to progressive disease. A reinduction of disease quiescence and adequate control of the lymphatic endothelium proliferation using a combination of sunitinib and low-dose taxol, can reinstitute disease stability. Indeed, after only a year of therapy, the child has remained stable for over 3 years.

In conclusion, a timely referral to vascular anomalies centers with expertise in diagnosis and management of GLA and GSD, leads to timely therapy. In these rare diseases, tailoring the therapy to the underlying biology represents a very rational alternative. Because large randomized double blind clinical trials would be difficult, it will be essential to share both positive and negative experiences with specific molecularly based therapies, and record the outcomes obtained with specific individualized protocols. As more and more angiogenesis inhibitors and biological response modifiers are becoming available in an “off label” setting, collaborative consortia should be used to share these strategies and define the best future approaches.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Website, www.jpho-online.com.

G.L.K. was funded by NIH RO1 GM93050, and by philanthropic funding of Newman Lakka Cancer Foundation.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wassef M, Blei F, Adams D, et al. Vascular anomalies classification: recommendations from the international society for the study of vascular anomalies. Pediatrics. 2015;136:e203–e214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorham LW, Stout AP. Massive osteolysis (acute spontaneous absorption of bone, phantom bone, disappearing bone); its relation to hemangiomatosis. Bone Joint Surg Am. 1955;37-A:985–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pastakia B, Horvath K, Lack EE. Seventeen year follow-up and autopsy findings in a case of massive osteolysis. Skeletal Radiol. 1987;16:291–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein M, Metelmann HR, Gross U. Massive osteolysis (Gorham-Stout syndrome) in the maxillofacial region: an unusual manifestation. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;25:376–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radhakrishnan K, Rockson SG. Gorham’s disease: an osseous disease of lymphangiogenesis? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1131:203–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Radhakrishnan K, Rockson SG. The clinical spectrum of lymphatic disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1131:155–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lala S, Mulliken JB, Alomari AI, et al. Gorham-Stout disease and generalized lymphatic anomaly—clinical, radiologic, and histologic differentiation. Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42:917–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batt RE, Michalski SR, Mahl T, et al. Postmenarchal development of chylous ascites in acrocephalosyndactyly with congenital lymphatic dysplasia. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(pt 2):829–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hassanein AH, Mulliken JB, Fishman SJ, et al. Lymphatic malformation: risk of progression during childhood and adolescence. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23:149–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heritier S, Le Merrer M, Jaubert F, et al. Retrospective French nationwide survey of childhood aggressive vascular anomalies of bone, 1988-2009. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu P, Yuan XG, Hu XY, et al. Gorham-Stout syndrome in mainland China: a case series of 67 patients and review of the literature. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2013;14:729–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez-Gutierrez JC, Miguel M, Diaz M, et al. Osteolysis and lymphatic anomalies: a review of 54 consecutive cases. Lymphat Res Biol. 2012;10:164–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grunewald TG, Damke L, Maschan M, et al. First report of effective and feasible treatment of multifocal lymphangiomatosis (Gorham-Stout) with bevacizumab in a child. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1733–1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klement G, Baruchel S, Rak J, et al. Continuous low-dose therapy with vinblastine and VEGF receptor-2 antibody induces sustained tumor regression without overt toxicity. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:R15–R24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hagendoorn J, Padera TP, Yock TI, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor-beta in Gorham’s disease. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2006;3:693–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rockson SG. The lymphatic continuum revisited. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1131:ix–x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brouillard P, Boon L, Vikkula M. Genetics of lymphatic anomalies. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:898–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zankl A, Duncan EL, Leo PJ, et al. Multicentric carpotarsal osteolysis is caused by mutations clustering in the amino-terminal transcriptional activation domain of MAFB. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90:494–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brice G, Mansour S, Bell R, et al. Analysis of the phenotypic abnormalities in lymphoedema-distichiasis syndrome in 74 patients with FOXC2 mutations or linkage to 16q24. J Med Genet. 2002;39:478–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghalamkarpour A, Morlot S, Raas-Rothschild A, et al. Hereditary lymphedema type I associated with VEGFR3 mutation: the first de novo case and atypical presentations. Clin Genet. 2006;70:330–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moalem S, Brouillard P, Kuypers D, et al. Hypotrichosis-lymphedema-telangiectasia-renal defect associated with a truncating mutation in the SOX18 gene. Clin Genet. 2015;87:378–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Irrthum A, Devriendt K, Chitayat D, et al. Mutations in the transcription factor gene SOX18 underlie recessive and dominant forms of hypotrichosis-lymphedema-telangiectasia. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1470–1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gabrielli O, Catassi C, Carlucci A, et al. Intestinal lymphangiectasia, lymphedema, mental retardation, and typical face: confirmation of the Hennekam syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1991;40:244–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meijer-Jorna LB, van der Loos CM, de Boer OJ, et al. Microvascular proliferation in congenital vascular malformations of skin and soft tissue. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:798–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirayama T, Sabokbar A, Itonaga I, et al. Cellular and humoral mechanisms of osteoclast formation and bone resorption in Gorham-Stout disease. J Pathol. 2001;195:624–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dickson GR, Mollan RA, Carr KE. Cytochemical localization of alkaline and acid phosphatase in human vanishing bone disease. Histochemistry. 1987;87:569–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Edwards JR, Williams K, Kindblom LG, et al. Lymphatics and bone. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hammill AM, Wentzel M, Gupta A, et al. Sirolimus for the treatment of complicated vascular anomalies in children. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57:1018–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kareva I, Waxman DJ, Lakka Klement G. Metronomic chemotherapy: an attractive alternative to maximum tolerated dose therapy that can activate anti-tumor immunity and minimize therapeutic resistance. Cancer Lett. 2015;358:100–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang J, Lou P, Lesniewski R, et al. Paclitaxel at ultra low concentrations inhibits angiogenesis without affecting cellular microtubule assembly. Anticancer Drugs. 2003;14:13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kerbel RS, Yu J, Tran J, et al. Possible mechanisms of acquired resistance to anti-angiogenic drugs: implications for the use of combination therapy approaches. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2001;20:79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shweiki D, Itin A, Neufeld G, et al. Patterns of expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and VEGF receptors in mice suggest a role in hormonally regulated angiogenesis. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:2235–2243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.