Abstract

Background

Epithelioid glioblastomas (E-GBMs) manifest BRAF V600E mutation in up to fifty percent of cases, compared to a small percentage of ordinary GBMs, suggesting they are best considered variants rather than a different pattern of GBM. Availability of a targeted therapy, vemurafenib, may make testing BRAF status important for treatment. It is unclear whether BRAF VE1 immunohistochemistry (IHC) can substitute for Sanger sequencing in these tumors.

Design

BRAF VE1 IHC was correlated with Sanger sequencing results on our original cohort of E-GBMs, and then new E-GBM cases were tested with both techniques (n=20). Results were compared to those in similarly-assessed giant cell GBMs, anaplastic pleomorphic xanthoastrocytomas (A-PXAs).

Results

All tumors tested showed 1:1 correlation between BRAF V600E mutational results and IHC. However, heavy background immunostaining in some negatively-mutated cases resulted in equivocal results that required repeat IHC testing and additional mutation testing using a different methodology to confirm lack of detectable BRAF mutation. Mutated/ BRAF VE1 IHC+ E-GBMs and A-PXAs tended to manifest strong, diffuse cytoplasmic immunoreactivity, compared to previously-studied GGs which demonstrate more intense immunoreactivity in the ganglion, than glial, tumor component. One of our E-GBM patients with initial gross total resection quickly recurred within 4 months, required a second resection, and then was placed on vemurafenib; she remains tumor-free 21 months after second resection without neuroimaging evidence of residual disease, adding to the growing number of reports of successful treatment of BRAF-mutated glial tumors with drug.

Conclusions

E-GBMs show good correlation between mutational status and IHC, albeit with limitations to IHC. E-GBMs can respond to targeted therapy.

Keywords: vemurafenib, targeted therapy, epithelioid glioblastoma, BRAF, anaplastic pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, Sanger sequencing

Introduction

Epithelioid GBMs (E-GBMs) are a subtype of GBM composed of cohesive sheets of patternless, closely-packed, variably lipidized, small- to medium-sized cells with rounded cytoplasmic profiles, eosinophilic cytoplasm, lack of cytoplasmic stellate processes, and absence of interspersed neuropil [1-6]. Tumors may additionally have rich reticulin investiture but, unlike pleomorphic xanthoastrocytomas with anaplastic features (A-PXAs), usually possess more cytologically-uniform cells and an absence of eosinophilic granular bodies (EGBs) [7, 8]. Unlike very rare rhabdoid GBMs, they retain immunostaining for nuclear INI-1 protein [9]. The cohesive nature of the tumor cells can lead to mistaken initial impression of metastatic neoplasm, especially metastatic melanoma [5, 9], until demonstration of immunostaining for glial fibrillary protein (GFAP), albeit irregular in distribution [9], proves diagnosis of a poorly differentiated GBM. In addition, tumors may be multifocal [5] and/or fairly sharply demarcated [9] on neuroimaging, further contributing preoperatively to the suspicion of metastatic disease.

Currently E-GBMs are not separately listed in the 2007 World Health Organization classification system [10], but appear to have unique clinicopathological features [2, 9], analogous to giant cell GBMs. Like giant cell GBMs, their unique features might better qualify them as variants rather than a pattern. The fact that E-GBMs possess BRAF V600E mutation in up to fifty percent of cases [11], compared to a small percentage of ordinary GBMs [12], further opens the possibility of targeted therapy with vemurafenib, a drug that has been used successfully for several years especially in melanoma patients with tumoral mutation [13. 14].

Our previous work utilized Sanger sequencing to document BRAF mutation in 7/13 EGBs and the absence of mutation in 7 giant cell GBMs [11]. This technique, however, is not available in all laboratories and is more costly and time-consuming than immunohistochemistry (IHC). In the current study, we re-interrogated our original E-GBM and giant cell GBM cases and tested all available cases by IHC, using the most widely-utilized BRAF mutation-specific antibody (VE1 clone, Ventana, Tucson, AZ, bought out from Spring Biosciences, Inc., Pleasanton, CA). After first demonstrating the principle that BRAF VE1 IHC might correlate with positive or negative Sanger sequencing in our original cohort [11], we extended our study to new cases of E-GBMs accrued since that publication as well as a subset of our original anaplastic pleomorphic xanthoastrocytomas (A-PXAs) which we had also previously assessed by Sanger sequencing, but not IHC [8]. We then compared the pattern of immunostaining we saw in these tumor types with our recently-published experience with gangliogliomas immunostained with the same antibody [15, 16].

Materials and Methods

Case accrual

All available immunoblank slides were retrieved from our files from our original E-GBMs and giant cell GBMs assessed by Sanger sequencing for BRAF V600E mutation [11], as were those from A-PXAs we had similarly studied [8]. Many of the original cases [8, 11] had been outside consultation cases and thus not all examples tested by Sanger sequencing for those studies still had immunoblank slides or paraffin blocks remaining in our archives and available for the current study.

After testing our previously published materials, we went forward with IHC and Sanger sequence testing on newly-accrued cases, focusing on new cases of E-GBMs seen since our original publications [9, 11]. All diagnoses had been made by the author (BKD).

Routine histology and immunohistochemistry

Tissues were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and cut at 5 microns; all staining/immunostaining was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections, not frozen material. Immunostains utilized for diagnostic purposes at the time of original assessment included glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, Dako Corporation, Carpentaria, CA, USA, polyclonal, 1:2500, no antigen retrieval), MIB-1 (Dako, monoclonal, 1:400 dilution, antigen retrieval), IDH1(Histobiotec, Miami Beach, FL, monoclonal, antigen retrieval), p53 (Dako, monoclonal, 1:200, antigen retrieval), and in many instances, S100 (Ventana, Tucson, AZ, USA, monoclonal, pre-dilute, antigen retrieval) and synaptophysin (Ventana, polyclonal, pre-dilute, antigen retrieval).

The available original E-GBMs and giant cell GBMs from our previous paper [11] were retrospectively immunostained for BRAF VE1 (Ventana, Tucson, AZ, USA, monoclonal, antigen retrieval); these represented both cases with and without the BRAF V600E mutation as originally assessed by Sanger sequencing for BRAF V600E mutation (see below).

BRAF VE1immunostaining was automated and conducted on a Benchmark Ultra stainer from Ventana/Roche, utilizing the proprietary antigen retrieval system necessary for this equipment as provided by the company, which is high pH (8.5). All immunostained sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. All newly accrued cases of E-GBMs were also both immunostained for BRAF VE1 and assessed for BRAF V600E mutation by Sanger sequencing (see below). Equivocal results for IHC were repeated and whenever possible, fresh-cut slides from the paraffin block were utilized in retesting equivocal results.

Methods for fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) had been conducted as part of the routine workup at the time of diagnosis in most E-GBM cases. Briefly, dual-color FISH probe sets, manufactured by Vysis (Abbott Laboratories Inc., Des Plaines, IL, USA), were used for amplification status of EGFR. To test for monosomy 22, DNA probes directed to 22q11.2 and 22q13 were used; this method detects most deletions but does not detect point mutations in chromosome 22. For analysis of PTEN, a PTEN (10q23)-specific DNA probe and a probe directed to the chromosome 10 centromere were used.

DNA sequencing for BRAF exon 15 mutation

In all cases optimal areas of tumor were identified by the author (BKD), microdissected using microscope assisted manual microdissection as needed and utilized for mutational testing, with microdissection of these areas to ensure that the testing was performed on areas enriched for at least 50% tumor cells.

DNA was extracted from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) material using the DNeasy FFPE extraction kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA) according to manufacturer's instructions. DNA yields were then quantified using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer ND-1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA).

For direct sequencing, approximately 10 ng of template DNA was PCR amplified using 5 pmol each of forward (5′TGCTTGCTCTGATAGGAAAAT3′) and reverse (5′TCAGGGCCAAAAATTTAATCA3′) BRAF exon 15 primers KAPA2G™ Robust HotStart Enzyme and PCR master mix with KAPA™ dNTP mix (KAPA Biosystems cat# KK5525 and KK1017) in a 25μl reaction. PCR was performed on an ABI 9700 thermocycler with an initial denaturing step at 95°C followed by 20 cycles of touchdown PCR (starting annealing temperature of 65°C, decremented 0.5°C per cycle) and 25 cycles at 94°C denaturation, 55°C annealing and 72°C extension finished by a 10 minute 72°C final extension. The resultant PCR products were purified with the QIAquick 96 well PCR cleanup kit (Qiagen cat# 28106). The purified PCR products were sequenced in forward and reverse directions using an ABI 3730 automated sequencer using BigDye Terminator Version 1.1 (Applied Biosystems). Each chromatogram was visually inspected for any abnormalities, using NM_004333.4 as a reference sequence, with particular attention directed to codon 600. Sequences were also evaluated using Mutation Surveyor software (Soft Genetics, State College, PA). Mutations were determined to be present when peaks reached a threshold value above baseline calculated from background level, combined with visual inspection of the chromatogram.

SNaPshot mutational assessment

Single nucleotide base extension (SNaPshot TM) assessment for BRAF c.1799T mutation, an assay with higher analytic (technical) sensitivity compared to Sanger sequencing, was performed on the subset of cases with equivocal IHC but negative Sanger results, with methods identical to those utilized in our previous study [16].

Results

Patient cohort

Of the original published cohort [11], 9 of 15 E-GBMs (2 negative for mutation, 7 positive for mutation) and 8 of 9 giant cell GBMs (all negative for mutation) had sufficient material remaining in our files for BRAF VE1 IHC testing. Of the original published A-PXA cohort [8], 6 of 10 cases assessed by Sanger sequencing were available for BRAF VE1 IHC (4 positive, 2 negative for mutation).

Eleven new cases of E-GBMs were identified, making a total of 20 total E-GBMs tested by both techniques. Clinical and demographic features are provided in the Table. Of the newly-accrued cases, 7 of the 11 new E-GBMs represented consultation cases from outside hospitals (see Table), with one seen as a consultation biopsy case from an outside hospital with subsequent resection at our facility (case 19). Although the majority of E-GBM cases were consultation cases, it is important to note that these cases had not been specifically submitted to rule out epithelioid GBM, i.e., they came from regional hospitals that often submit brain biopsy specimens to us for diagnosis. Thus, these cases of E-GBMs were not exceptional and had come up in routine community hospitals in daily practice, underscoring that the E-GBM subtype is not exceedingly rare. All but one of these had been referred with the suspicion of high grade glioma. The exception was a case that had originally been diagnosed at the outside hospital as a metastatic melanoma to brain until her case had been presented at the local Tumor Board at the referring hospital and it became evident that she did not have an antecedent history of melanoma (case 17). The brain biopsy was then submitted to our institution for a second opinion. Unlike our original series where we focused primarily on relatively “pure” epithelioid GBMs, in this study we expanded our cohort to include those with more focal epithelioid features (n=5, cases 12, 13, 18, 19, 20).

Table. Clinical, Immunohistochemical, Mutational Features of E-GBMs.

| Patient age, gender, year of surgical biopsy/resection. C= consultation case Tumor location/Surgical procedure | Diagnosis | BRAF V600E mutational status confirmed by Sanger sequencing | BRAF VE1 IHC | FISH for EGFR, PTEN, monosomy 22, LOH 1p, 19q | IDH1 IHC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPITHELIOID GLIOBLASTOMAS from original series* | |||||||

| 1 | 27 F 2001 Left occipital Resection |

Primary epithelioid GBM | V600E mutation present | Positive for cells with EGFR amplification | IDH1 negative | ||

| 2 | 43 M 2003 C Left temporal-Parietal Resection |

Primary epithelioid GBM | V600E mutation present | Negative for monosomy of Ch. 22 | IDH1 negative | ||

| 3 | 10 F 2009 2009 (2 surgical procedures same year) Right parieto-occipital Biopsy Resection |

Primary epithelioid GBM | V600E mutation present | Strong, diffuse VE1 IHC+ | Negative for EGFR amplification Negative for loss of PTEN (10q23)sequences Negative for monosomy of Ch. 22 |

IDH1 negative | |

| 4 | 29 M 2012 Left temporal lobe Resection |

Primary epithelioid GBM | V600E mutation present | Strong, diffuse VE1 IHC+ | Negative for EGFR amplification Low level loss of PTEN and 10 centromere consistent with monosomy 10 Negative for monosomy of Ch. 22 |

IDH1 negative | |

| 5 | 21 F 2012 C Right temporal lobe Resection |

Primary epithelioid GBM | V600E mutation present | Strong, diffuse VE1 IHC+ | Negative for amplification of EGFR sequences Negative for loss of PTEN sequences Weak EGFR expression |

IDH1 negative | |

| 6 | 29 F 2012 C Left temporal-parietal lobe Resection |

Primary epithelioid GBM | V600E mutation present | Strong, diffuse VE1 IHC+ | Negative for amplification of EGFR sequences Positive for loss of PTEN and 10 centromere sequences, consistent with monosomy 10 |

IDH1 negative | |

| 7 | 50 M 2012 Left temporal lobe Resection C |

Primary epithelioid GBM | V600E mutation present | Strong, diffuse VE1 IHC+ | Negative for amplification of EGFR sequences Positive for loss of PTEN and 10 centromere sequences, consistent with monosomy 10 |

IDH1 negative | |

| 8 | 41 M 2003 Right frontal Resection |

Secondary epithelioid GBM arising as a well-demarcated enhancing mass in cavity of previous surgical resection bed Previous mixed oligoastrocytoma, WHO grade II 2 years prior |

No mutation present | BAF47 Retained in all tumor nuclei | Negative for monosomy of Ch. 22 Negative for LOH 1p, 19q (testing performed on epithelioid glioblastoma) |

IDH1 positive | |

| 9 | 14 M 2011 Right frontal lobe Biopsy |

Primary epithelioid GBM | No mutation present | BAF47 Retained in all tumor nuclei | Rare cells with amplification of EGFR (1.8%); other cells with polysomy (3-4, 43.6%), and high polysomy for Ch. 7 (≥5, 35.0%) | IDH1 negative | |

| NEW E GBMs since publication* | |||||||

| 10 | 55 M 2013 Left temporal lobe Excisional biopsies C |

Primary epithelioid GBM | V600E mutation present | Strong, diffuse VE1 IHC+ | Genetic testing not performed | IDH1 negative | |

| 11 | 39 F 2014 Left frontal lobe Resection C |

Primary epithelioid GBM | V600E mutation present | Strong, diffuse VE1 IHC+ | Negative for amplification of EGFR sequences Negative for loss of PTEN sequences |

IDH1 negative | |

| 12 | 32 F 2014 Right parietal lobe Resection C |

Primary GBM with focal epithelioid and admixed giant cell GBM features | V600E mutation present | Strong, diffuse VE1 IHC+ | Positive for rare cells with amplification of EGFR sequences Positive for rare cells with amplification of PTEN sequences |

IDH1 negative | |

| 13 | 69 M 2014 Left parietal lobe Resection |

Primary GBM with focal epithelioid features | V600E mutation present | Strong, diffuse VE1 IHC+ | No amplification of EGFR Positive for PTEN mutation ^ |

IDH1 negative | |

| 14 | 63 M 2013 Left temporal lobe Resection |

Primary epithelioid GBM | No mutation present | Equivocal VE1 IHC | Negative for amplification of EGFR sequences Negative for loss of PTEN sequences |

IDH1 negative | |

| 15 | 53 M 2014 Left parietal lobe Resection C |

Primary epithelioid GBM | No mutation present | Negative VE1 IHC | Negative for amplification of EGFR sequences Positive for loss of PTEN and 10 centromere sequences, consistent with monosomy 10 |

IDH1 negative | |

| 16 | 56 M 2014 Left frontal lobe Biopsies |

Primary epithelioid GBM | No mutation present | Negative VE1 IHC | Genetic testing not performed | IDH1 negative | |

| 17 | 82 F 2014 Left frontal lobe Biopsies C |

Primary epithelioid GBM | No mutation present | Negative VE1 IHC | Genetic testing not performed | IDH1 negative | |

| 18 | 63 M 2014 Left frontal lobe Resection C |

Primary GBM with focal epithelioid features | No mutation present | Equivocal VE1 IHC | Positive for amplification of EGFR sequences Positive for loss of PTEN and 10 centromere sequences, consistent with monosomy 10 |

IDH1 negative | |

| 19 | 35 M 2014 Right temporal lobe Biopsies C and resection |

Primary GBM with focal epithelioid features | No mutation present | Negative VE1 IHC | Negative for amplification of EGFR sequences Borderline positive for loss of PTEN and 10 centromere sequences, consistent with monosomy 10 |

IDH1 negative (also IDH1/2 mutational negative) | |

| 20 | 55 M 2014 Cerebellum Resection |

Radiation induced GBM with focal epithelioid and admixed giant cell/pleomorphic GBM features | No mutation present | Equivocal VE1 IHC | Negative for amplification of EGFR sequences Population of cells with monosomy 10 and population with loss of PTEN relative to 10 centromere |

IDH1 negative | |

Key: M=male, F=female, IHC=immunohistochemistry, GBM=glioblastoma, Ch.=chromosome;

= Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Aisner DL, Birks DK, et al. Epithelioid GBMs show a high percentage of BRAF V600E mutation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:658-698,

=testing performed at University of California-San Diego

Overall age range for the E-GBM cohort in which both BRAF VE1 IHC and Sanger sequencing results were available was 10-82 years with 6 cases age < 30 years, younger than most GBMs [10] (see Table). 19/20 cases were negative for IDH1 by immunohistochemistry; the sole positive case was a secondary GBM as previously reported from our original paper [11]. FISH had been conducted in most of the E-GBM cases as part of the original diagnostic assessment (17/20, see Table) and, since available, we provide those results (Table). FISH results in our larger E-GBM cohort confirm our original impression [11] that no particular pattern is characteristic of E-GBMs, except possibly that EGFR amplification in more than a few rare cells was uncommon.

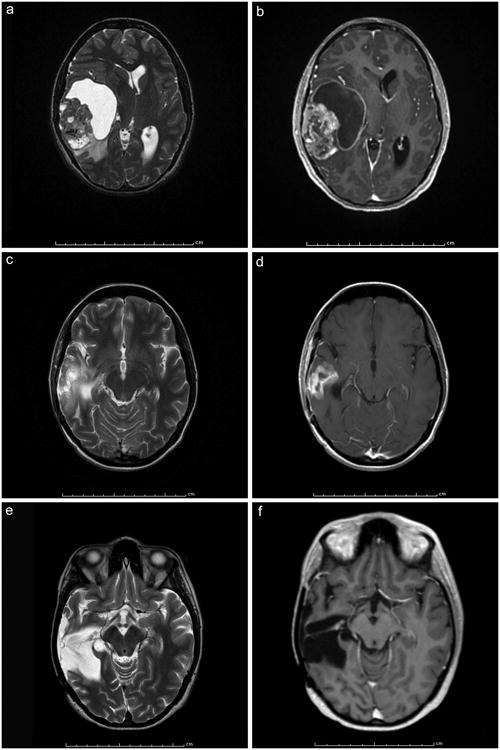

One of our original E-GBM patients with tumor showing BRAF mutation has, since publication, been treated with the targeted drug vemurafinib (case 5). Her original tumor showed the characteristic relatively-demarcated, mixed cystic and solid features typical of many E-GBMs [11], with the cyst highlighted on the T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging scans (Figure 1a) and the enhancement on T1-weighted MRI with gadolinium (Figure 1b). She then received radiation therapy but suffered a rapid recurrence, 5 months after initial surgery and less than 3 months after completion of radiation, requiring re-excision of the tumor. MRIs after this recurrence showed new signal in the tumor bed (Figures 1c, d). Recurrence rather than therapy-induced necrosis was confirmed at surgery. She then received treatment with vemurafenib, to a dose of 960 mg. twice daily as her only therapy. She is still receiving this medication 23 months after recurrence, with an excellent quality of life. MRIs show no recurrence after receipt of drug (Figures 1 e, f, at 19 months post second surgery); her most recent scan at 23 months was also negative for recurrent/progressive tumor.

Figure 1.

a, b. Axial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans pre-resection from the E-GBM from our original series [11] treated with targeted therapy; note the cystic component seen as bright white peri-tumoral signal on (a), the enhancement (b), and relatively sharp demarcation from surrounding brain (b). T2-weighted (a) and T1-weighted with contrast (b).

c, d. Axial MRIs after rapid recurrence had occurred 5 months post resection and less than 3 months after completion of radiation therapy. Recurrence rather than therapy-induced necrosis was confirmed at surgery. T2-weighted (c) and T1-weighted with contrast (d).

e, f. Axial MRIs at 19 months post second surgery show no recurrence after treatment with vemurafenib only, to a dose of 960 mg twice daily. The complete absence of enhancing tumor in the tumor bed is best seen on (f). She is still receiving this medication 21 months after recurrence, with an excellent quality of life. T2-weighted (e) and T1-weighted with contrast (f).

Histology results

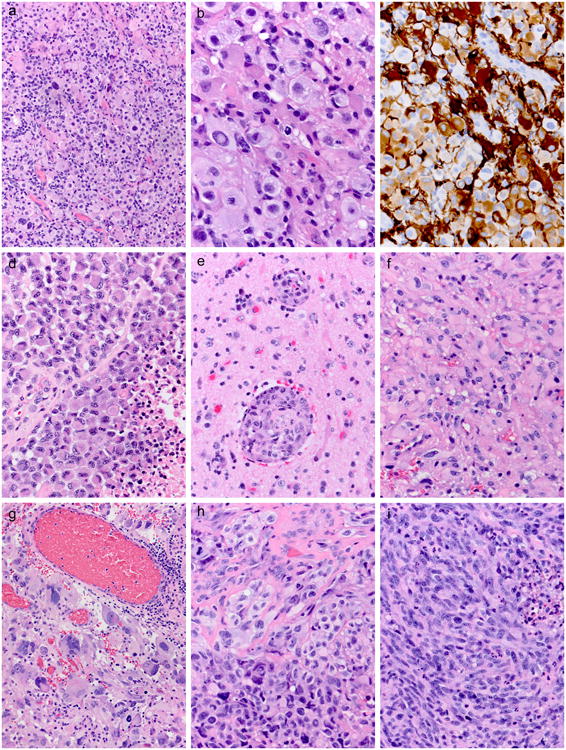

Histological features detailed in our original E-GBM and giant cell GBM paper [11] and in our A-PXA paper [8] on those cohorts are not repeated here. Six of the 11 new E-GBMs were almost identical histologically to cases in our original series [11] and these tumors contained a majority of epithelioid tumor cells and had been “pure” E-GBMs. The 6 new “pure” E-GBM cases demonstrated the pathognomonic cohesive sheets of patternless, closely-packed (Figure 2a), variably lipidized, small- to medium-sized cells with rounded cytoplasmic profiles, eosinophilic cytoplasm, lack of cytoplasmic stellate processes, and absence of interspersed neuropil (Figure 2b). As previously described [11], GFAP could be quite variable from one area to another in the tumor or between cells (Figure 2c). Necrosis was often not associated with pseudopalisading of tumor cells or with prominent microvascular proliferation (Figure 2d). Both limited individual cell infiltration into the surrounding parenchyma and occasional perivascular tumor spread (Figure 2e) could be found.

Figure 2.

a. Low power view of one of the new E-GBM cases demonstrates the pathognomonic cohesive sheets of patternless, closely-packed cells. Case 10 illustrated. Hematoxylin and eosin, 200×.

b. This same case at higher magnification shows the typical rounded cytoplasmic profiles, eosinophilic cytoplasm, lack of cytoplasmic stellate processes, and absence of interspersed neuropil. Case 10 illustrated. Hematoxylin and eosin, 600×.

c. GFAP could be quite variable from one area to another in the tumor and from one cell to the next. Case 10 illustrated. Immunostaining for glial fibrillary acidic protein with light hematoxylin counterstain, 400×.

d. Most of our E-GBM cases manifested near-pure populations of epithelioid cells, usually of small to medium size; necrosis (lower right) was usually not associated with pseudopalisading of tumor cells or microvascular proliferation. Case 11 illustrated. H&E, 400×.

e. In a few cases where adjacent brain tissue was included with the tumor resection material, perivascular tumor spread could be found. Case 11 illustrated. H&E, 400×.

f. Two of our new cases manifested a less-pure epithelioid phenotype; Case 12 had relatively discrete areas with epithelioid cells of small to medium size. H&E, 400×.

g. Other areas from the same case showed classic features of giant cell GBM, even with co-associated non-neoplastic lymphocytes. Case 12 illustrated. H&E, 200×.

i. Case 13 manifested a rich admixture of epithelioid and pleomorphic cells in some areas. H&E, 400×.

j. Other areas from the same case consisted solely of elongate, pleomorphic cells and these areas were more prevalent. H&E, 400×.

Five of 11 of our new cases manifested a less-pure, more focal epithelioid phenotype. Case 12 had relatively discrete areas with small epithelioid cells (Figure 2f) and others with giant cell features, with the latter showing non-neoplastic lymphocytes (Figure 2f). Case 13 manifested a rich admixture of epithelioid and spindled, pleomorphic cells in a few regions (Figure 2g), but in most of the tumor the predominant population was that of elongate, pleomorphic cells (Figure 2i). Cases 18, 19, and 20 all had focal epithelioid features with either admixtures of fibrillary (cases 18, 19) or large pleomorphic tumor cells (Case 20). Case 20 was notable since it was a radiation-induced GBM of the cerebellum in a patient with remote history of ependymoma in childhood for which he had received radiation therapy. Although only 2 of these 5 mixed cases eventually proved to have the BRAF V600E mutation (see below), this suggests that even when the epithelioid component is a focal component of a GBM, BRAF testing should be considered.

BRAF VE1 immunohistochemistry correlation with Sanger sequencing for BRAF V600E mutation

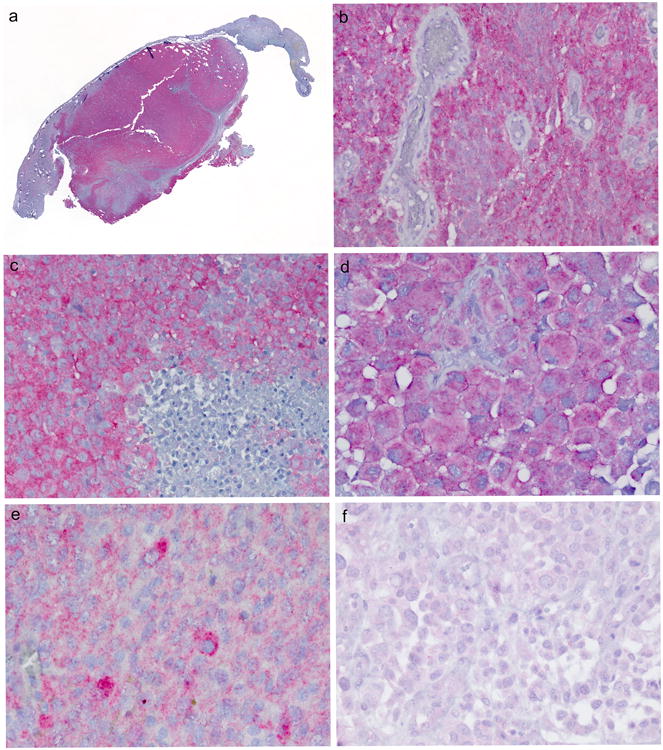

All previously-reported, dually-assessed E-GBMs, giant cell GBMs and A-PXAs showed good concordance between Sanger sequencing results and BRAF VE1 IHC. Immunostaining of the original cohort is illustrated in Figure 3 and the bright red chromagen yielded intensely-positive results in tumor, but not adjacent dura (Figure 3a), blood vessels (Figure 3b), or necrotic foci (Figure 3c) in the same section. Immunostaining was diffuse, crisp, usually of uniform intensity throughout the cytoplasm of tumor cells, and highlighted the epithelioid phenotype (Figure 3d). Two of the 7 immunopositive original cases showed variability in staining quality in the tissue, but we noted that these were the oldest cases in our series (cases 1, 2) and the immunoblank slides available in our archives for testing may have been of the oldest age. Tissue did not remain in the block for newer sections. Both, however, showed convincing positive immunostaining in some regions of the tissue. One of these E-GBMs additionally showed some variability in intensity of immunostaining from cell to cell (Figure 3e, case 2 illustrated). Two of the assessable cases had been negative for BRAF mutation and were also negative by IHC (Figure 3f, case 9 illustrated).

Figure 3.

a, b, c. Immunostaining of the original cohort of E-GBM showed that the bright red chromagen utilized with the BRAF VE1 antibody yielded intensely-positive, convincing results in tumor but not dura to which the tumor was attached (Figure 3a), blood vessels within tumor (Figure 3b), or necrotic foci (lower right, Figure 3c). Cases 6 (a), 5 (b), 2 (c) illustrated. Immunostaining with BRAF VE1 antibody with light hematoxylin counterstain, whole mount, 400×, 600×, respectively.

d. Immunostaining was diffuse and usually uniform throughout the cytoplasm and highlighted the epithelioid phenotype. Case 3 illustrated. Immunostaining with BRAF VE1 antibody with light hematoxylin counterstain, 600×.

e. One of the 7 immunopositive original cases showed some variation in immunostaining intensity from cell to cell. Case 2 illustrated. Immunostaining with BRAF VE1 antibody with light hematoxylin counterstain, 600 ×.

f. Both mutational-negative original E-GBMs that could be tested by BRAF VE1 antibody were negative. Case 9 illustrated. 400×

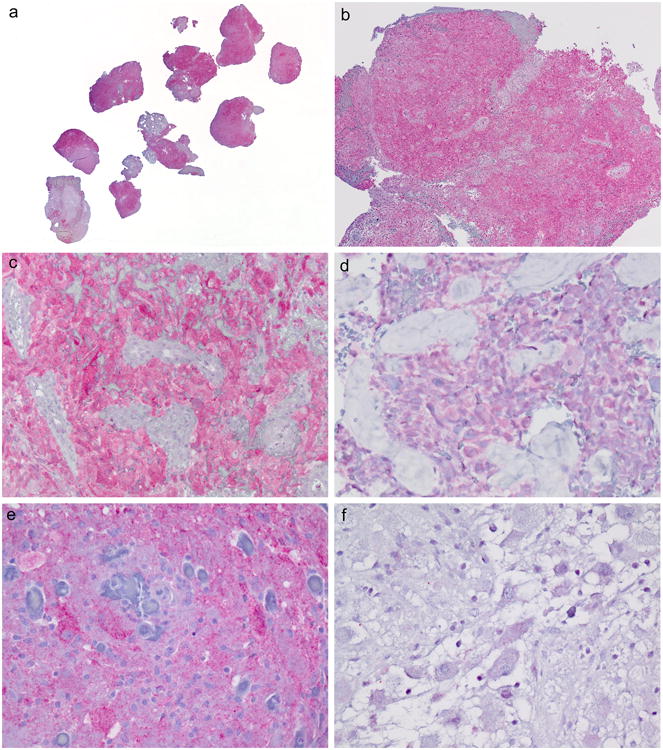

New E-GBMs further highlighted the uniform immunostaining with BRAF VE1 immunohistochemistry, with sparing only of non-tumorous areas on the slide (Figure 4a). With use of immunoblank slides <2 years of age in our archives, all tumor areas were uniformly immunoreactive on the slide (Figure 4b). Two of the 5 cases with focal epithelioid features (case 12 with epithelioid [Figure 2e] and giant cell features [Figure 2f]; case 13 with an admixture of epithelioid and pleomorphic cells [Figure 2h] as well as non-epithelioid areas [Figure 2i] showed diffuse uniform immunostaining in both tumor components (Figure 4c). The other three were initially equivocal by IHC (Figure 4d) although subsequent repeat immunostaining on the same section suggested these were likely negative. Nevertheless, we further tested these three equivocal E-GBMs by a technique with greater analytic (technical) sensitivity, SNaPshotTM, on the possibility that they represented cases with lower mutational burden than could be detected by Sanger sequencing. These three cases were also negative for mutation by this technique (cases 14, 18, 20).

Figure 4.

a. New E-GBMs further highlighted the uniform immunostaining with BRAF VE1 immunohistochemistry, with sparing only of non-tumorous areas on the slide. Case 10 illustrated. Immunostaining with BRAF VE1 antibody with light hematoxylin counterstain, whole mount section.

b. For new E-GBMs, all immunoblank slides were <2 years of age in our archives and all tumor areas were uniformly immunoreactive on the slide. Case 10 illustrated. Immunostaining with BRAF VE1 antibody with light hematoxylin counterstain, 40×.

c. In our two new cases where epithelioid morphology was more focally seen, the BRAF VE1 IHC was present in both components. Case 12 illustrated. Immunostaining with BRAF VE1 antibody with light hematoxylin counterstain, 200×.

d. New E-GBM with weak/equivocal immunostaining that required further mutational analysis; this case was negative by both Sanger sequencing and SNaPshot TM. Immunostaining with BRAF VE1 antibody with light hematoxylin counterstain, 400×

e. Gangliogliomas positive for mutation/protein expression showed significantly stronger immunostaining in the neoplastic ganglion cell component of the tumor than in the glial tumor component. Immunostaining with BRAF VE1 antibody with light hematoxylin counterstain, 400×

f. Gangliogliomas negative for mutation/protein expression were negative in both the neoplastic ganglion cell and glial components of tumor. Immunostaining with BRAF VE1 antibody with light hematoxylin counterstain, 400×

Reassessing clinical and demographic features with the IHC/mutational results above showed that of the 11 mutated/IHC+ E-GBM cases, 6 were female, 5 were male (Table). Most of the patients < age 30 years in the study did show mutation/IHC+ (5/6 examples), but the overall cohort numbers are clearly too small for firm conclusions.

All 8 assessable giant cell GBMs were negative, all of which were assessed on freshly-cut immunoblank slides prepared from paraffin blocks still available in our archives. We were able to immunostain 6 of our 10 original A-PXAs [8] and there was 1:1 concordance in 6 of 6 cases, albeit with more variation in immunostaining intensity throughout the slide than for our E-GBMs. Once again, fresh cut slides from the block were necessary in all cases to achieve concordant IHC results with the known mutational status (4 originally positive, 2 negative for mutation). Although the numbers of these cases were small (n=6), it appeared that while the immunostaining was also uniform throughout the tumor population, it appeared to be weaker in intensity than what we generally encountered for immunopositive E-GBMs.

GGs as previously reported by our group [15] showed that immunopositive cases manifesting stronger immunoreactivity in the ganglion cell component (Figure 4e) than the glial component, but never in the glial cell component alone. Indeed, the strong immunostaining in positive cases served to highlight the neoplastic ganglion cells, but in negatively mutated/negatively immunostained cases, both tumor components were equally negative (Figure 4f).

Thus, limitations in the immunostaining exist with this commercial antibody, at least in our hands, even after multiple diligent attempts made to optimize parameters of staining technique. First, very strong diffuse, crisp cellular immunostaining results with the red chromagen were indisputably positive, and were able to be achieved in our study with all mutationally-positive new E-GBMs as well as our original E-GBMs. Some loss of antigen fidelity with older-cut archival slides was noted. Second, negative IHC correlated with negative mutational status in almost all examples, but the immunostain requires experience to interpret because of the background that sometimes occurs. Heavy background leads to equivocal results in some cases. We first tried repeating the IHC procedure but then further assessed the case by Sanger sequencing and in equivocal cases the “heavy background cases” ultimately proved negative by mutational testing even with SNapshotTM. Thus, given the importance of accurate documentation of BRAF mutational status prior to potential use of targeted therapy, we continue to test cases with heavy background/“hue” by mutational analysis accompanied by microdissection to ensure an appropriately high proportion of tumor in the tested sample.

Discussion

Combining our newly-assessed E-GBMs (11 cases) with our original cohort [11] (13 cases) we show that 7/13 original and 4/11 new E-GBMs (11/24, 46%) are mutated for BRAF V600E and in tested cases, there was concordance between strong, crisp BRAF VE1 IHC and positive Sanger sequencing results. There were no significant differences in histological features between BRAF-mutated and non-mutated examples and now with our larger numbers of cases, there are also no significant demographic differences. We also show in this study that reasonable IHC results occur for A-PXAs, although the available cohort for testing (n=6) was too small for strong conclusions.

It is not known what mutational event leads to epithelioid formation in high grade gliomas, although a recent, in-depth study of a single case by array comparative genomic hybridization separately performed for epithelioid versus non-epithelioid areas of a GBM hinted at possibly causation [17]. Specifically, Nobusawa et al. demonstrated BRAF V600E mutation both in epithelioid tumor cells and in diffusely infiltrating less atypical astrocytoma cells in the same tumor [17]. In contrast, eight shared copy number alterations (CNAs) and three CNAs were observed only in epithelioid cells; one of the latter was a homozygous deletion of a tumor suppressor gene, LSAMP, at 3q13.31 [17]. Thus the BRAF mutation was not confined to the epithelioid component, even when confined to focal areas within a tumor. This parallels our findings in this study in that the 2/5 cases with focal epithelioid features that were BRAF VE1 IHC positive showed strong uniform immunostaining in both tumor components.

BRAF VE1 antibody results were reported by Koelsche et al. in a 2013 study in which GGs were assessed [18]. Protein expression was predominantly identified in the ganglion cell component of the tumor but no case showed immunostaining in the glial component alone [18]. We found a similar IHC pattern exists in pediatric brainstem gliomas [15] and conversely noted that widely metastatic GGs of the spinal cord in adults were both VE1 IHC and Sanger sequencing negative for BRAF, all using the same laboratory and techniques [16]. In contrast, in E-GBMs, as well as the few A-PXAs we had available for the current study, the distribution of immunostaining was usually more uniform and diffuse than what was seen in GGs. There was a good correlation in our E-GBMs (n=17), giant cell GBMs (n=8), and A-PXAs (n=6) between the IHC and Sanger sequencing results, but with significant limitations in the antibody.

Background immunostaining results in a subset of cases required repeat immunostaining despite every attempt at optimization of the protocol. Our experience of difficulty with the BRAF antibody parallels those reported by others [19-22]. Specifically, in colorectal cancers the authors had to optimize conditions, but when this was done, similar to our study, there was excellent concordance between IHC and mutational results (using the antibody from Spring Biosciences) [22]. Interestingly, 1 of 4 of their cases which had been scored as having weak immunostaining proved to have BRAF V600E mutation [22], also underscoring the need to follow up the occasional weak/equivocal result to appropriately classify mutational status. They further studied the optimal antigen retrieval method and found it to be EDTA buffer (pH 6.0) [22]. This parallels our use of high pH buffer and the proprietary buffer from the same manufacturer.

Concordance between IHC and mutational analysis with pituitary tumors has not been good [19-21]. To our knowledge there is no alternate biological reason for immunopositive BRAF VE1 immunostaining in a tumor except for the presence of BRAF V600E mutation and thus we feel the background immunostaining is likely technical and not due to an alternative pathway that upregulates BRAF protein expression. We also do not favor a low-level mutation in these equivocal cases since SNaPshot testing was also negative. We specifically microdissected optimal tumor areas for mutational testing and thus dilution by non-tumoral elements is unlikely to account for negative results in the three cases with equivocal IHC. While heterogeneity for BRAF mutation is a possible explanation for discordant IHC and mutational results, this study specifically shows that BRAF protein expression (using a mutation-specific antibody) appears to be quite homogeneous throughout the tumor population in E-GBMs, even in non-pure cases, thus leading to the likely explanation that when the positive results of immunostaining represent true positive findings for BRAF mutation, the cells are homogeneously impacted.

As of 2014, we recommend using IDH1 antibody differently from the BRAF VE1 antibody. With IDH1 IHC, when the result is clearly immunopositive (and in our experience the immunostain has high fidelity and is usually easy to interpret, with either all tumor cells positive or negative), then no additional mutational confirmation is necessary. If IDH1 IHC is negative, then mutational testing for IDH1/ IDH2 mutation should be done in select patient groups including younger patients to rule out the rare types of IDH1/IDH2 mutation not detected by the antibody; a predictive algorithm has been recently developed and is online for directing IDH1/2 testing [23].

For BRAF VE1 IHC, completely negative IHC appears to preclude the need mutational testing for BRAF V600E, at least when fresh-cut blanks are utilized. Thus far, all very strongly IHC+ E-GBM cases in our experience equate with the positive presence of BRAF V600E mutation. However, heavy background/“hue” IHC occurs more often than is desirable, even with antibody optimization. We first repeat IHC testing and then, if still equivocal, proceed to mutational assessment by molecular methods. This recommendation of proceeding to mutational assessment in cases with equivocal/ weak IHC is concordant with the recommendation for colorectal tumors [22].

Finally, the need a more cost-effective method for screening BRAF mutational status in a significant subset of different glial tumor types is obvious. Although anecdotal, BRAF IHC immunopositive/Sanger sequencing positive glial tumors have shown clinical response with the targeted therapy, vemurafinib. Although this favorable response to therapy has been well-established in BRAF-mutated patients with metastatic melanoma [13 14], it is unlikely that large cohorts of far less-common E-GBMs, A-PXAs or even GGs can be similarly accrued in rapid fashion without multi-institutional efforts.

Indeed, to date, while only individual reports of patients with these uncommon brain tumor types and BRAF mutation responsive to vemurafenib have appeared [24-29], the evidence is accumulating that the drug is effective in various types of BRAF-mutated glial tumors. These have included 2 pediatric anaplastic supratentorial GGs (both with illustrated BRAF IHC+) [24], a pediatric brainstem GG [25], a pediatric GBM which interestingly also had focal epitheloid features (Figure 2c in paper) [26], 4 of 5 treated adult recurrent or progressive PXAs [27, 28], a pilomyxoid astrocytoma [29], and now an adult E-GBM. Furthermore, we have seen a recurrent pediatric A-PXA with BRAF mutation (but not included in our study of adult A-PXAs [8]) with stabilization on drug (unpublished observation, NKF). Collectively, this suggests the potential for targeted therapy, a particularly exciting prospect in WHO grade IV gliomas such as E-GBMs, even if a less-frequent GBM tumor type.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank The Morgan Adams Foundation and the Molecular Pathology Shared Resource of the University of Colorado's NIH/NCI Cancer Center Grant P30CA046934 for financial support of this project, Mrs. Diane Hutchinson for expert manuscript preparation, and Ms. Lisa Litzenberger for photographic expertise.

Footnotes

Presented in abstract format at the 90th annual meeting of the American Association of Neuropathologists, Portland, Oregon, June, 2014

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Rosenblum MK, Erlandson RA, Budzilovich GN. The lipid-rich epithelioid glioblastoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:925–934. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199110000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuller GN, Goodman JC, Vogel H, et al. Epithelioid glioblastoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1998;57:501. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akimoto J, Namatame H, Haraoka J, et al. Epithelioid glioblastoma: a case report. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2006;22:21–27. doi: 10.1007/s10014-005-0173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodriguez FJ, Scheithauer BW, Giannini C, et al. Epithelial and pseudoepithelial differentiation in glioblastoma and gliosarcoma: a comparative morphologic and molecular genetic study. Cancer. 2008;113:2779–2789. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gasco J, Franklin B, Fuller GN, et al. Multifocal epithelioid glioblastoma mimicking cerebral metastasis: case report. Neurocirugia (Astur) 2009;20:550–554. doi: 10.1016/s1130-1473(09)70133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanaka S, Nakada M, Hayashi Y, et al. Epithelioid glioblastoma changed to typical glioblastoma: the methylation status of MGMT promoter and 5-ALA fluorescence. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2011;28:59–64. doi: 10.1007/s10014-010-0009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giannini C, Scheithauer BW, Burger PC, et al. Pleomorphic Xanthoastrocytoma. Cancer. 1999;85:2033–2045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt Y, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Aisner DL, et al. Anaplastic PXA in adults: case series with clinicopathologic and molecular features. J Neurooncol. 2013;111:59–69. doi: 10.1007/s11060-012-0991-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Alassiri AH, Birks DK, et al. Epithelioid versus rhabdoid glioblastomas are distinguished by monosomy 22 and immunohistochemical expression of INI-1 but not claudin 6. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:341–354. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181ce107b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kleihues P, Burger PC, Aldape KD, et al. Glioblastoma. In: Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. Albany, New York: WHO Publications Center; 2007. pp. 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Aisner DL, Birks DK, et al. Epithelioid GBMs show a high percentage of BRAF V600E mutation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:658–698. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31827f9c5e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schindler G, Capper D, Meyer J, et al. Analysis of BRAF V600E mutation in 1,320 nervous system tumors reveals high mutation frequencies in pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, ganglioglioma and extra-cerebellar pilocytic astrocytoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121:397–405. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0802-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. Improved Survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2507–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sosman JA, Kim KB, Schuchter L, et al. Survival in BRAF V600-mutant advanced melanoma treated with vemurafenib. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:707–714. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donson AM, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Aisner DL, et al. Pediatric Brainstem gangliogliomas show BRAF V600E mutation in a high percentage of cases. Brain Pathol. 2014;24:173–183. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lummus SC, Aisner DL, Sams SB, et al. Massive Dissemination From Spinal Cord Gangliogliomas Negative for BRAF V600E: Report of Two Rare Adult Cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2014;142:254–260. doi: 10.1309/AJCPIBSV67UVJRQV. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nobusawa S, Hirato J, Kurihara H, et al. Intratumoral heterogeneity of genomic imbalance in a case of epithelioid glioblastoma with BRAF V600E mutation. Brain Pathol. 2014;24:239–246. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koelsche C, Wohrer A, Jeibmann A, et al. Mutant BRAF V600E protein in ganglioglioma is predominantly expressed by neuronal tumor cells. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;125:891–900. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sperveslage J, Gierke M, Capper E, et al. VE1 immunohistochemistry in pituitary adenomas is not associated with BRAF V600E mutation. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;125:911–912. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mordes DA, Lynch K, Campbell S, et al. VE1 antibody immunoreactivity in normal anterior pituitary and adrenal cortex without detectable BRAF V600E mutations. Am J Clin Pathol. 2014;141:811–815. doi: 10.1309/AJCP37TLZLTUAOJL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farzin M, Toon CW, Clarkson A, et al. BRAF V600E mutation specific immunohistochemistry with clone VE1 is not reliable in pituitary adenomas. Pathology. 2014;46:79–80. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0000000000000033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuan SF, Navina S, Cressman KL, et al. Immunohistochemical detection of BRAF V600E mutant protein using the VE1 antibody in colorectal carcinoma is highly concordant with molecular testing but requires rigorous antibody optimization. Hum Pathol. 2014;45:464–472. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2013.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Li, Voronovich Z, Clark K, Hands I, Mannas J, Walsh M, Nikiforova MN, Durbin EB, Weiss H, Horbinski C. Predicting the likelihood of an isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 or 2 mutation in diagnosis of infiltrative glioma. Neuro-oncology. 2014 May 23; doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou097. e pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bautista F, Paci A, Minard-Colin V, et al. Vemurafenib in pediatric patients with BRAFV600E mutated high-grade gliomas. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61:1101–3. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rush S, Foreman N, Liu A. Brainstem ganglioglioma successfully treated with vemurafenib. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:e159–60. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinson GW, Orr BA, Gajjar A. Complete clinical regression of a BRAF V600E-mutant pediatric glioblastoma multiforme after BRAF inhibitor therapy. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:258. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chamberlain MC. Salvage therapy with BRAF inhibitors for recurrent pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma: a retrospective case series. J Neurooncol. 2013;114:237–40. doi: 10.1007/s11060-013-1176-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee EQ, Ruland S, LeBoeuf NR, et al. Successful treatment of a progressive BRAF V600E-mutated anaplastic pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma with vemurafenib monotherapy. J Clin Oncol. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.1766. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skrypek M, Foreman N, Guillaume D, et al. Pilomyxoid astrocytoma treated successfully with vemurafenib. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014 May 12; doi: 10.1002/pbc.25084. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]