Abstract

Adeno-associated virus rhesus isolate 8 (AAVrh.8) is a leading vector for the treatment of neurological diseases due to its efficient transduction of neuronal cells and reduced peripheral tissue tropism. Toward identification of the capsid determinants for these properties, the structure of AAVrh.8 was determined by X-ray crystallography to 3.5 Å resolution and compared to those of other AAV isolates. The capsid viral protein (VP) structure consists of an αA helix and an eight-stranded anti-parallel β-barrel core conserved in parvoviruses, and large insertion loop regions between the β-strands form the capsid surface topology. The AAVrh.8 capsid exhibits the surface topology conserved in all AAVs: depressions at the icosahedral twofold axis and surrounding the cylindrical channel at the fivefold axis, and three protrusions around the threefold axis. A structural comparison to serotypes AAV2, AAV8, and AAV9, to which AAVrh.8 shares ~84, ~91, and ~87% VP sequence identity, respectively, revealed differences in the surface loops known to affect receptor binding, transduction efficiency, and antigenicity. Consistent with this observation, biochemical assays showed that AAVrh.8 is unable to bind heparin and does not cross-react with conformational monoclonal antibodies directed against the other AAVs compared. This structure of AAVrh.8 thus identified capsid surface differences which can serve as template regions for rational design of vectors with enhanced transduction for specific tissues and escape pre-existing antibody recognition. These features are essential for the creation of an AAV vector toolkit that is amenable to personalized disease treatment.

Keywords: AAV vectors, Neurotropism, Capsid structure, Parvovirus, X-ray crystallography, Gene therapy

INTRODUCTION

Viral vectors based on the non-pathogenic parvovirus adeno-associated virus (AAV) show great promise as gene delivery vectors due to their ability to deliver packaged foreign genes for stable and long-term protein expression in a wide range of human tissues (reviewed in (Flotte and Carter, 1995; Mingozzi and High, 2011)). They serve as the first approved gene therapy treatment (Salmon et al., 2014). These non-enveloped, single-stranded (ss) DNA packaging viruses belong to the genus Dependoparvovirus of the family Parvoviridae and require co-infection with a helper virus such as Adenovirus for replication (Bowles et al., 2006; Cotmore et al., 2014). Currently, clinical trials are underway with AAV vectors packaging therapeutic genes for the treatment of several diseases, including alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency, Leber’s congenital amaurosis, muscular dystrophy, hemophilia B, cystic fibrosis, Alzheimer’s disease, arthritis, lipoprotein lipase deficiency, Parkinson’s disease, and HIV infection (e.g. (Carter, 2006; Coura Rdos and Nardi, 2007; Daya and Berns, 2008; Mueller and Flotte, 2008; Nathwani et al., 2011; Stieger et al., 2011)). Challenges for these clinical studies include the need to (I) improve viral-tissue specificity and (II) decrease the detrimental effects of the host immune response against the vector (especially for treatments that may require vector re-administration) (e.g. (Boutin et al., 2010; Michelfelder and Trepel, 2009; Tseng and Agbandje-McKenna, 2014)). In an effort to overcome these issues several novel AAV serotypes/variants have been isolated from nonhuman sources to exploit their varied tissue tropisms, transgene expression efficiencies, and expected lack of human immune system recognition.

To date, thirteen AAV serotypes (AAV1–13) and ~150 gene sequences have been isolated from human/non-human primate tissues (Gao et al., 2004). Amino acid sequence comparison between these serotypes shows ~60–99% identity, with AAV4 and AAV5 being the most different (Gao et al., 2004). Of these 13 serotypes, AAV1, AAV2, AAV3, AAV5, AAV6, and AAV9 have human hosts (Atchison et al., 1965; Bantel-Schaal and zur Hausen, 1984; Gao et al., 2004; Georg-Fries et al., 1984; Hoggan et al., 1966; Melnick et al., 1965; Muramatsu et al., 1996; Rutledge et al., 1998), AAV4, AAV7, AAV8, AAV10, and AAV11 were isolated from nonhuman primates (Blacklow et al., 1968; Gao et al., 2002; Mori et al., 2004), and AAV12 and AAV13 were contaminants of Adenovirus stocks (Schmidt et al., 2008a; Schmidt et al., 2008b). AAVrh.8, isolated from rhesus macaques, shares the highest sequence identity with AAV8 at 91% (Gao et al., 2004). Recent preclinical studies with AAVrh.8 have demonstrated that it efficiently transduces the retina, and crosses the blood-brain barrier (BBB) to transduce neuronal cells while also displaying reduced tropism for peripheral tissues (Giove et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2014). AAV9 and AAVrh.10 (another rhesus isolate) can also cross the BBB to target the central nervous system (CNS) (Foust et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2011) . Due to these properties AAVrh.8, AAVrh.10, and AAV9 are being actively developed for treatment of neurological disorders.

The AAVs package their linear ssDNA genome of ~4.7 kb into a T=1 icosahedral capsid with a diameter of ~260 Å. The capsids are assembled from 60 copies (in total) of three viral proteins (VPs), VP1 (~87 kDa), VP2 (~73 kDa), and VP3 (~61 kDa) encoded from the cap gene and stochastically incorporated in an estimated ratio of 1:1:10, respectively (Buller and Rose, 1978; Johnson et al., 1971; Rose et al., 1971; Snijder et al., 2014). The VPs share a common C-terminal sequence (~520 amino acids; within VP3), with the entire sequence of VP3 contained within VP2, and all of VP2 contained within VP1, which has a unique N-terminal region of 137 amino acids (VP1u). Currently, structures of nine serotype members, AAV1–9, serving as the representative members of the AAV antigenic clades and clonal isolates, and AAVrh32.33, have been determined using X-ray crystallography and/or cryo-electron microscopy and image reconstruction (cryo-reconstruction) (DiMattia et al., 2012; Govindasamy et al., 2006; Govindasamy et al., 2013; Kronenberg et al., 2001; Lerch et al., 2010; Mikals et al., 2014; Nam et al., 2007; Ng et al., 2010; Padron et al., 2005; Walters et al., 2004; Xie et al., 2011; Xie et al., 2002) (and unpublished data). Only the common VP3 region is observed in the structures. The conserved common core regions, which include a βA strand, an eight stranded β-barrel motif (βB-βI), and an α-helix (αA), are superposable while the apex of the loops inserted between the β-strands vary in sequence and structure. These regions are defined as variable regions (VRs) I-IX based on the comparison of two structurally diverse serotypes, AAV2 and AAV4 (Govindasamy et al., 2006). The VRs cluster at the icosahedral five-, three-, and twofold axes of symmetry to produce local variations on the capsid surface. Mutagenesis, biochemical, and structural studies demonstrate that residues in these VRs play important functional roles, including receptor attachment, transduction determination, and immunogenic reactivity (reviewed in (Adachi et al., 2014; Gurda et al., 2012; Gurda et al., 2013; Kotchey et al., 2011; Li et al., 2008; Lochrie et al., 2006; Pulicherla et al., 2011; Raupp et al., 2012)).

In this study, the high resolution structure of AAVrh.8 was determined by X-ray crystallography to 3.5 Å resolution in an effort to pinpoint the capsid surface regions that differ in sequence and structure for this serotype and possibly responsible for its neuronal tropism. Similar to other AAV structures, only the VP3 common region of AAVrh.8 is ordered and conserves the VP topology. Comparison to selected AAV VP3 structures, AAV2, AAV8, and AAV9, identified the largest differences at VR-I and VR-IV with main-chain shifts of up to ~10 and ~5 Å, respectively, compared to AAV9. Minor main-chain shifts, for example up to 1.5 Å, were observed in the other VRs. However, significant differences were observed in some of the amino acid side-chain orientations even for conserved residues within these VRs. A heparin binding analysis showed lack of interaction for AAVrh.8 in contrast to the AAV2 positive control. In addition, native dot blot showed a lack of cross-reactivity with monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) and human donor serum directed against conformational AAV2, AAV8, and AAV9 epitopes. While these functional annotations are limited, the observations are consistent with published reports that residues within the VRs control receptor attachment and antigenicity for the AAVs. The AAVrh.8 structure thus identified surface loop regions to be (I) tested in an effort to pinpoint its neurotropism determinant, (II) modified in the development of AAVrh.8 and other AAV-based vectors for tissue-targeted gene therapy applications, and (III) modified in the development of vectors to evade pre-existing antibody responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus production and purification

The recombinant vector used in this study, AAV2/rh8.TBG.GFP.BGH, was manufactured by PennVector at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, PA) as previously described (Wang et al., 2005). Briefly, a plasmid containing the enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) transgene cDNA driven by the thyroxine binding globulin promoter and bovine growth hormone gene polyadenylation signal and flanked by AAV2 inverted terminal repeats, was packaged into the AAVrh.8 capsid by triple transfection using calcium phosphate precipitation. The helper construct used was the pAdΔF6 adenovirus helper plasmid. The recombinant rAAVrh.8-GFP vector was purified by three rounds of cesium chloride centrifugation and buffer-exchanged into phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The vector titer (genome copies/ml (gc/ml)) was determined by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). For crystallization, the purified sample was concentrated to ~10 mg/ml using Apollo concentrators (Orbital Biosciences, MA) (150 kDa molecular-weight cutoff) by centrifugation at 2300 x g at 277 K into PBS or Tris-HCl buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 6% glycerol (v/v)). The purity and integrity of the vectors was assessed by 12% SDS-PAGE with GelCode Blue staining (ThermoScientific, IL) and negative-stain electron microscopy (EM), respectively. For the EM visualization, samples were negatively stained with NanoW (Nanoprobes, NY) and viewed on an FEI Tecnai G2 Spirit electron microscope, as described in Halder et al (Halder et al., 2012b).

Crystallization, X-ray diffraction data collection, and data processing

Crystallization conditions were screened by varying the buffer (PBS or Tris-HCl), the concentration of polyethylene glycol 8000 (PEG 8000) (3–5.5% w/v), and NaCl (0.15–1.0 M). The crystal screens were set up using the hanging-drop vapor-diffusion method (McPherson, 1982) in VDX 24-well plates with siliconized cover slips (Hampton Research, Laguna Niguel, CA). Crystallization drops consisted of vector sample in the PBS or Tris-HCl buffer mixed with reservoir solution at a 1:1 ratio (v/v) and equilibrated against 1 ml of reservoir solution at RT.

Prior to data collection, the crystals were soaked for 30 s in cryoprotectant solution consisting of the reservoir solution and 30% glycerol (v/v) and flash-cooled in a liquid-nitrogen stream. A total of 302 X-ray diffraction images were collected from a single crystal at the F1 beamline at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY) on an ADSC Quantum 270 CCD detector. Data collection parameters were: crystal-to-detector distance of 400 mm, oscillation angle of 0.3° per image, exposure time of 40 s per image, and λ = 0.9186 Å . The crystal diffracted X-rays to ~3.5 Å resolution. The reflections were indexed and integrated with the HKL2000 suite of programs and scaled with SCALEPACK (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997). The crystals grew in the primitive orthorhombic crystal system with unit cell dimensions of a = 355.5, b = 358.9, and c = 371.5 Å. Inspection of the h00, 0k0, and 00l classes of reflections demonstrated systematic absence patterns for the odd reflections, consistent with three mutually perpendicular 21 screw axes and the space group P212121. The data set scaled with an Rsym of 17.6% and completeness of 90.0%. The data processing statistics are given in Table 1. Based on the unit-cell parameters and the P212121 space group, packing considerations suggested the presence of four capsids per unit cell with one capsid in the crystallographic asymmetric unit. The Matthew’s coefficient (VM) was calculated to be 2.19 Å3Da−1 (assuming molecular weight of rAAVrh.8-GFP = ~5.4 × 106 Da), corresponding to a solvent content of 44% (Matthews, 1968).

Table 1.

Data collection, processing, and refinement statistics of AAVrh.8 structure

| Parameter | AAVrh.8 |

|---|---|

| Wavelength (λ, Å) | 0.9186 |

| No. of films | 302 |

| Space Group | P212121 |

| Unit cell parameters (Å, °) |

a=355.5, b=358.9, c=371.5 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50–3.5 |

| (3.6–3.5)a | |

| Total number of reflections | 8,236,295 |

| No. of unique reflections | 532,197 (50,545) |

| Crystal mosaicity (°) | 0.3 −0.5 |

| Completeness (%) | 90.0 (86.0) |

| Rsymb (%) | 17.6 (37.0) |

| Rpimc (%) | 12.8 (33.0) |

| Redundancy (N) | 2.8 (2.1) |

| I/σ | 3.2 (1.2) |

| VM (Å3/Da) | 2.19 |

| No. of atoms | 4120/11/22/1 |

| (protein/H20/DNA/ion) | |

| Average Bfactor (Å2) | 50.4/39.4/74.7/50.9 |

| (protein/H20/DNA/ion) | |

| Rfactord/Rfreee (%) | 23.2/23.4 |

| R.M.S.D bonds (Å) and angles (°) | 0.008, 1.45 |

| Ramachandran Statistics (%) | 98.1/1.9/0 |

| Most favored/Allowed/Outliers |

Values in parenthesis are for the highest resolution shell.

Rsym=ΣhklΣi|Ii(hkl)-<I(hkl)>|/ΣhklΣiIi(hkl)×100, where Ii(hkl) is the ith intensity of an individual reflection with indices h, k, l and <I(hkl)> is the average intensity of all symmetry equivalent measurements of that reflection; the summation is over all intensities.

Rpim=Σhkl[1/(N-1)1/2] Σi|Ii(hkl)-<I(hkl)>|/ΣhklΣiIi(hkl)×100, where Ii(hkl) is the ith intensity of an individual reflection with indices h, k, l and N is the redundancy, and <I(hkl)> is the average intensity of all symmetry equivalent measurements of that reflection; the summation is over all intensities.

Rfactor=(Σ|Fo|-|Fc|/Σ|Fo|)×100, where Fo and Fc are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes, respectively.

Rfree is calculated the same as Rfactor, except that it uses 5% of the reflection data partitioned from the refinement process.

Structure determination and refinement

The orientations of the four virus capsids in the crystal unit cell were determined with a self-rotation function (Rossmann and Blow, 1962) using the General Lock Rotation Function (GLRF) program (Tong and Rossmann, 1997) with 10% of the observed data between 10.0 and 5.0 Å resolution as large terms to search for the fivefold, threefold, and twofold symmetry axes of the virus capsid with κ = 72°, 120°, and 180°, respectively. The κ = 72° search was consistent with four capsid orientations related by a twofold along the unit cell axis.

The structure was determined by molecular replacement with AAV8 as the phasing model (Rossmann et al., 1992). A Cα model of the AAV8 VP3 crystal structure (PDB accession no. 2qa0; (Nam et al., 2007)) was generated by the MOLEMAN program (Kleywegt and Jones, 1997) and expanded to 60 subunits (one capsid) by icosahedral matrix multiplication using the Oligomer Generator subroutine available at the VIPERdb website (http://viperdb.scripps.edu/) (Carrillo-Tripp et al., 2009). Molecular replacement, utilizing rotation and translation function searches, and evaluation for packing clashes, was carried out using the phenix.automr subroutine in the PHENIX program (Adams et al., 2010). The best solution gave a Log Likelihood Gain (LLG) score of 2886, z-score for rotation function of 42.0 and z-score for translation function of 78.8 and Rfactor of 40.1% (Rfactor = (Σ |Fo|-|Fc|/Σ |Fo|)×100 where Fo are the observed structure factors and Fc are structure factors calculated from the model), with an orientation, in Eulerian angles, of α=222.46°, β=88.84°, and γ=149.77° and fractional coordinate position of 0.008, 0.000, and −0.005. An AAV8 VP3 polyalanine model (from PDB accession no. 2qa0; (Nam et al., 2007)) was generated by the MOLEMAN program (Kleywegt and Jones, 1997) and superimposed individually onto the 60 subunits of the oriented and positioned AAV8 Cα capsid model to generate the 60 non-crystallographic symmetry (NCS) operators required for subsequent refinement steps using the CNS program (Brunger et al., 1998). A subset of reflections (5%) was partitioned for monitoring of the refinement process and used to calculate Rfree (same as Rfactor but calculated with only 5% of randomly selected data) (Brunger, 1993). The initial phases were improved using simulated annealing, energy minimization, conventional position, and individual temperature factor (atomic displacement, measured in Å2, termed B-factor) refinement while applying strict 60-fold NCS in CNS (Brunger et al., 1998). Following the first cycle of refinement, real-space 60-fold NCS averaged σ-weighted Fo-Fc and 2Fo-Fc electron density maps (with Fo and Fc defined as above) were generated in CNS (Brunger et al., 1998) using a VP3 molecular mask, and used for model-building in the COOT program (Emsley et al., 2010).

A total of 519 amino acid residues, interpreted as positions 218 to 736 (VP1 numbering) of AAVrh.8 VP (here after referred to as VP3), were fitted into the averaged density maps by interactive substitution, insertion, and deletion of amino acids relative to the initial AAV8 VP3 polyalanine model using the COOT program (Emsley et al., 2010). Phases were generated and improved by several alternating cycles of refinement, real-space electron density averaging, and model rebuilding until there was no further improvement in the agreement between the Fo and Fc structure factors as monitored by the Rfactor. To improve the quality of the map, density modification was carried out using the Density Modification subroutine in the CNS program which performed solvent flattening and NCS averaging (Brunger et al., 1998). Additional unassigned ordered density (Fo-Fc density at a threshold of >5.0 σ) in the capsid interior consistent with a purine nucleotide (NT) was modeled as dAMP. An occupancy value of 0.7 was determined for the NT following a test of occupancy values from 0.3–1.0 to achieve acceptable B-factor values that were also comparable to that of the surrounding amino acid residues. The resolution of the averaged density map was insufficient to determine unambiguously the identity of the purine base. In addition to the nucleotide density, a stretch of positive density was observed in the averaged Fo-Fc map (at >3.0 σ) inside the channel at the icosahedral fivefold axis of the capsid which could be modeled as the N-terminus of one copy of VP3 (residues 204 – 210). This stretch of amino acids was excluded from refinement because it exhibited high structural dynamics (high B-factors) possibly due to different conformations of the VP3 common N-terminal sequence which is incompatible with the NCS constrained refinement and density averaging. Further unassigned averaged positive Fo-Fc density (a ≥3.0 σ) were modeled and refined as 11 water molecules (within hydrogen-bonding distances) and one Cl− ion with acceptable B-factors.

The quality of the refined VP3 structure was analyzed using the COOT and MOLPROBITY programs (Chen et al., 2010; Emsley et al., 2010). The root mean square deviations (R.M.S.D) from ideal bond lengths and angles were obtained from the CNS program (Brunger et al., 1998) and the average Bfactor for the VP3 model, solvent molecules, NT, and ions were calculated using the MOLEMAN program (Kleywegt and Jones, 1997). The refinement statistics are listed in Table 1. The figures were generated using the PYMOL (DeLano, 2002), UCSF-Chimera (Pettersen et al., 2004), and RIVEM (Xiao and Rossmann, 2007) programs.

Protein structure accession number

The refined AAVrh.8 VP3 coordinate and structure factors have been deposited in the RCSB PDB database under accession no. 4RSO.

Structural comparison of AAVrh.8 to other AAV structures

The refined AAVrh.8 VP3 crystal structure was superposed onto the VP3 structures of AAV2, AAV8, and AAV9 (PDB accession no. 1lp3, 2qa0, and 3ux1, respectively) (DiMattia et al., 2012; Nam et al., 2007; Xie et al., 2002) using the secondary structure matching (SSM) program available in PDBefold (Krissinel and Henrick, 2004) to identify similar and VRs. This program superposes Cα positions and gives the atomic distances (in Å) between aligned Cα positions and calculates the overall R.M.S.D for the aligned Cα positions. Based on this information and as previously defined (Govindasamy et al., 2006), VRs were identified that contain two or more residues with Cα atom distances of ≥1.0 Å apart between the superposed structures.

Heparin binding assay

To confirm a prediction that AAVrh.8 will not bind heparan sulfate (HS), the heparin binding profile of AAVrh.8 and AAV2 (positive control) was analyzed using microspin columns (732–6204; Biorad) loaded with 500 µL of heparin-conjugated agarose type I resin (H-6508; Sigma). The affinity column was equilibrated with 1 ml of 1X TD buffer (1X PBS, 1mM MgCl2, 2.5mM KCl), and then charged by washing with 1 ml of 1X TD/1 M NaCl buffer followed by two sequential washes with 1 ml of 1X TD buffer. The column was loaded with 100 ng of virus sample in 300 µL of 1X TD buffer followed by sequential collection of flow through, four column washes with 1X TD buffer (1 ml each), and elution with increasing concentrations of NaCl in 1X TD buffer (1.5 ml of 0.05–1.0 M NaCl). The input, flow through, washes, and elution fractions were boiled at 100 °C for 10 min and detected by dot blot hybridization as described in Gurda et al (Gurda et al., 2012) using the B1 MAb that recognizes a linear epitope located at the C-terminus of the AAV VP (Wobus et al., 2000).

Antigenic reactivity

To probe the AAVrh.8 antigenic properties in lieu of available anti-AAVrh.8 MAbs, the cross-reactivity of this vector for MAbs raised against AAV2 (A20) (Wobus et al., 2000), AAV8 (ADK8) (Sonntag et al., 2011) and AAV9 (ADK9) (Sonntag et al., 2011) capsids was tested by dot blot hybridization as described in Gurda et al (Gurda et al., 2012). In addition, the antigenic reactivity of AAVrh.8 was tested against commercially available human donor sera (Valley Biomedical, Cat. # HS-1004; Lot #s 4K1933-02 (donor serum #2), 4K1933-8 (donor serum #8), and 4K1933-15 (donor serum #15). A total of 100 ng (in 30 µL) of each virus was loaded onto the nitrocellulose membrane prior to incubation with the MAbs or human donor sera. To verify that virus was loaded, samples were boiled at 100 °C for 10 min and detected with the B1 antibody which recognizes denatured AAV capsids (Wobus et al., 2000). The B1 and A20 MAbs were used at a dilution of 1:3000 and 1:1000, respectively, while the ADK8 and ADK9 were used at dilution of 1:50. The human donor sera were used at dilution of 1:500.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Vector purification and crystallization

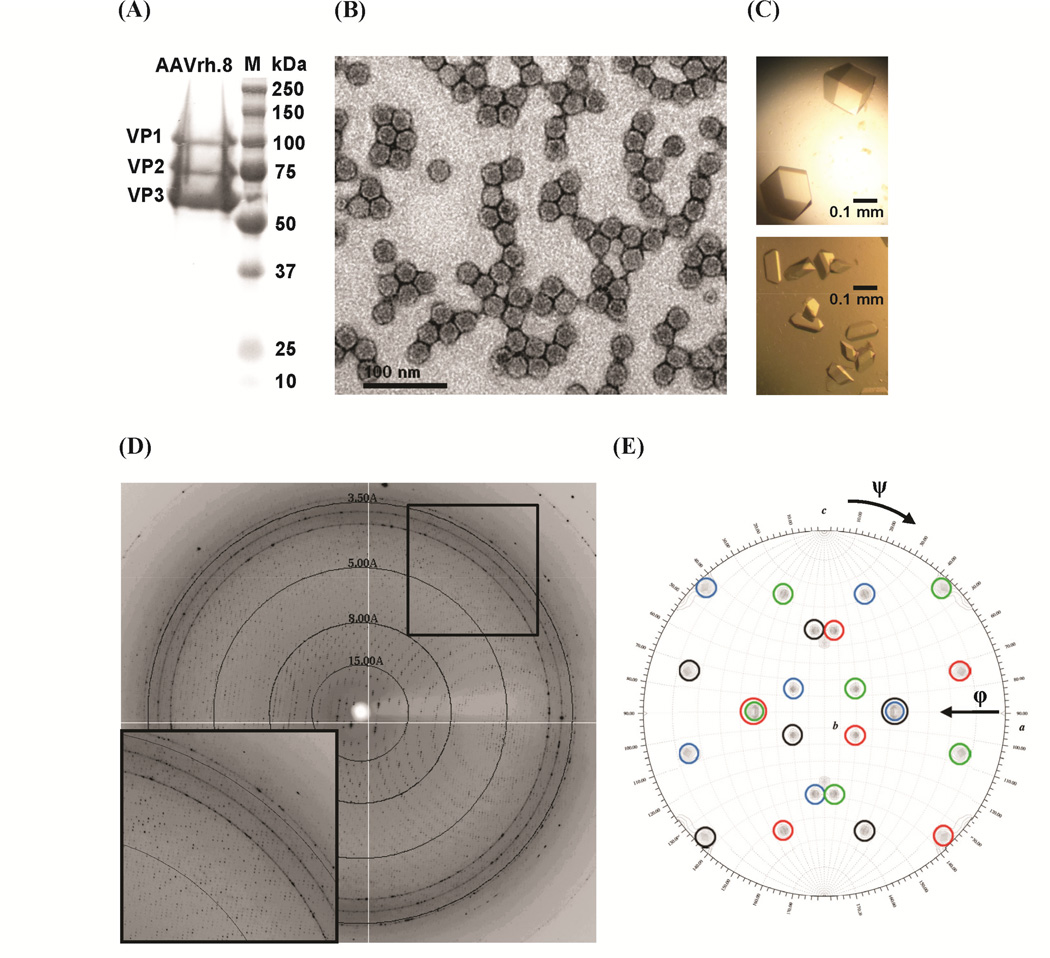

The titers for the purified rAAV.rh8-GFP vectors were in the range of 7×1012-2×1013 gc/ml, which is consistent with yields for other rAAV vectors. The vector sample contained VP1–3, as expected, and was pure as confirmed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1A). Negative-stain EM showed the capsids to be intact (Fig. 1B). Crystals were obtained from both the PBS (5.5% PEG 8000) and Tris-HCl screens (3–5% PEG 8000, 1 M NaCl) in ~ 1 week and were of different habits and sizes (Fig. 1C). Diffraction data was collected on crystals obtained from both screens, but only those grown in PBS, which diffracted X-rays to ~3.5 Å resolution (Fig. 1D and Table 1), were used for structure determination. The data from the crystals grown in Tris-HCl were mosaic and therefore not useful. The orientations of the four capsid molecules in the unit cell were evident in the self-rotation function (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1.

Characterization of the rAAV.rh8-GFP vector, crystallization, and X-ray diffraction data. (A) 12% SDS-PAGE image of purified vector showing VP1, VP2, and VP3. Molecular weight standards (M) are as shown. (B) Negatively stained electron micrographs, viewed at 30,000X magnification. (C) Optical photograph of crystals (~0.2–0.3mm3) from the PBS (top) and Tris-HCl (bottom) screens. (D) X-ray diffraction pattern. The image is a 0.3° oscillation and the concentric rings indicate the 15.0, 8.0, 5.0, and 3.5 Å resolution shells. The inset shows a close-up of the boxed region in the upper right-hand corner. (E) Stereographic proje ctions of the self-rotation function search for κ = 72°, searching for the fivefold icosahedral symmetry elements. The peaks belonging to each of the four capsid orientations in the unit cell are circled in black, blue, red, and green, respectively. The a, b, and c axes are labeled.

The AAVrh.8 crystal structure

The AAVrh.8 VP3 structure was refined to 3.5 Å resolution with Rfactor and Rfree values of 23.2% and 23.4%, respectively. The average NCS correlation coefficient was 0.90. The refinement and molecular geometry statistics are consistent with those reported for other virus structures determined at comparable resolution, as documented in VIPERdb website (http://viperdb.scripps.edu/) (Carrillo-Tripp et al., 2009), and also calculated by the Polygon subroutine (Urzhumtseva et al., 2009) in the program PHENIX (Adams et al., 2010). The similarity of Rfactor and Rfree values for virus structures is due to the high non-crystallographic icosahedral symmetry of the capsid that results in strong correlations between the reflections in the working and test data sets, thus limiting the ability to select truly random unique reflections for the Rfree calculation.

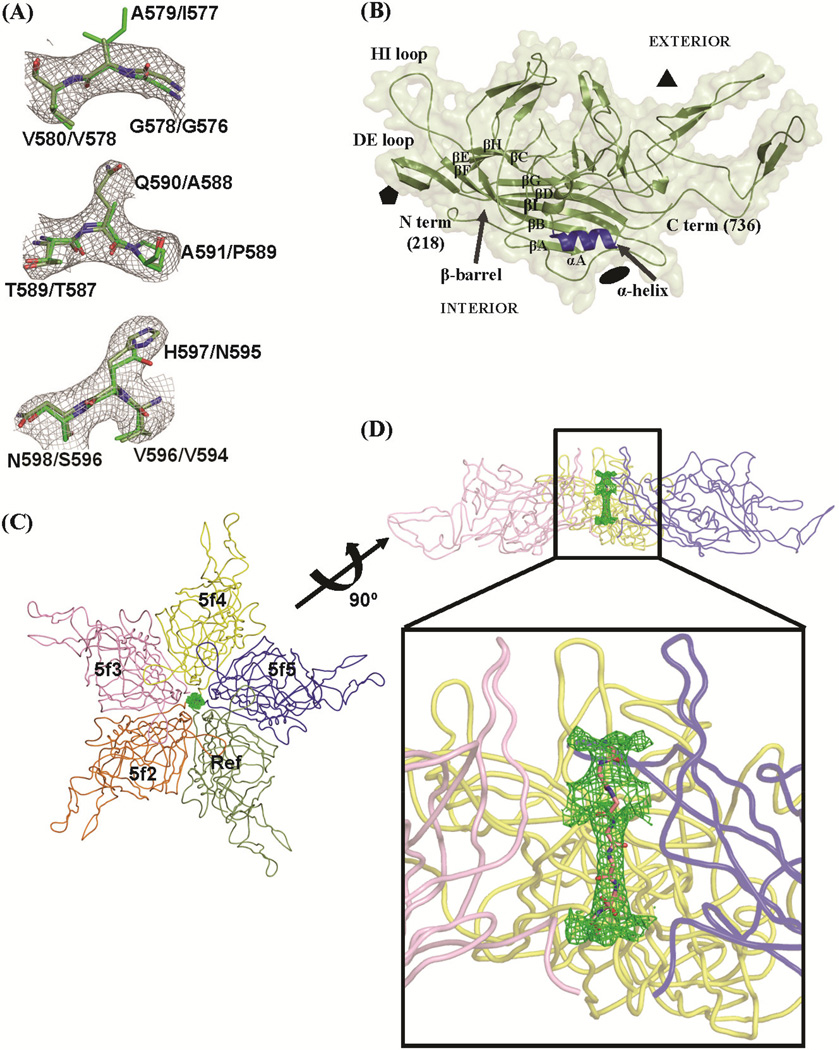

Although all three viral proteins were present in the AAVrh.8 vector sample, only residues 218–736 (VP1 numbering) which comprises most of the VP1/VP2/VP3 common region were ordered in the icosahedrally averaged electron density maps. Representative sections of the NCS-averaged 2Fo-Fc electron density map are shown in Fig. 2A. The resolution was suitable for accurate assignment of the AAVrh.8 VP3 amino acid side-chains, surface loops, and secondary structure elements (Fig. 2B) and demonstrated that there was no phase bias from the closely related AAV8 phasing model (Fig. 2A). Amino acid residues 1–217, which includes the VP1u (1–137), the VP1/2 common region (138–202), and the first 15 N-terminal residues of VP3 are disordered in the density maps. Density within the fivefold channel interpreted as residues 204–210 could not be refined due to high thermal motion. This lack of N-terminal VP ordering is consistent with all known parvovirus structures determined to date, except for B19 (reviewed in (Chapman and Agbandje-McKenna, 2006; Halder et al., 2012a)). It is postulated that the low copy numbers of VP1 and VP2 in the capsid (Snijder et al., 2014) or different conformations adopted by the VP1–3 N-termini, which is incompatible with the icosahedral averaging employed during structure determination, and/or intrinsic disorder predicted for the VP1/2 common region (Venkatakrishnan et al., 2013) are responsible for the lack of ordering in this region.

Figure 2.

The AAVrh.8 VP3 crystal structure. (A) Sections of the 2Fo-Fc electron density map contoured at threshold of 1.0 σ (grey mesh) for a stretch of residues that differ between AAVrh.8 and AAV8. The coordinates are shown as a stick model: C atom, dark green (AAVrh.8) or light green (AAV8); O atom, red; N atom, blue. The residues are labeled for AAVrh.8/AAV8. (B) Ribbon diagram of the VP3 within its transparent density surface. The conserved β-barrel core motif (βBIDG-βCHEF), αA helix (blue), N- and C-termini, DE and HI loops, and the interior/exterior sides of VP3 are labeled. The approximate positions of icosahedral two-, three-, and fivefold symmetry axes are depicted as a black filled oval, triangle, and pentagon, respectively. (C) A pentamer of VP3 monomers viewed down the fivefold axis and looking inside the capsid, showing the icosahedral reference (Ref) and fivefold (5f2–5f5), symmetry relationships. The Fo-Fc density in the channel at the fivefold axis is contoured at a threshold of ~3.5σ (green mesh). (D) A 90° rotated view of (C) with the Ref and 5f2 monomers removed from view for clarity. The polypeptide stretch (residues 204–210) modeled inside the channel is depicted in the stick form. The inset shows a close-up view of the boxed region. The figures were generated using the PyMol program (DeLano, 2002).

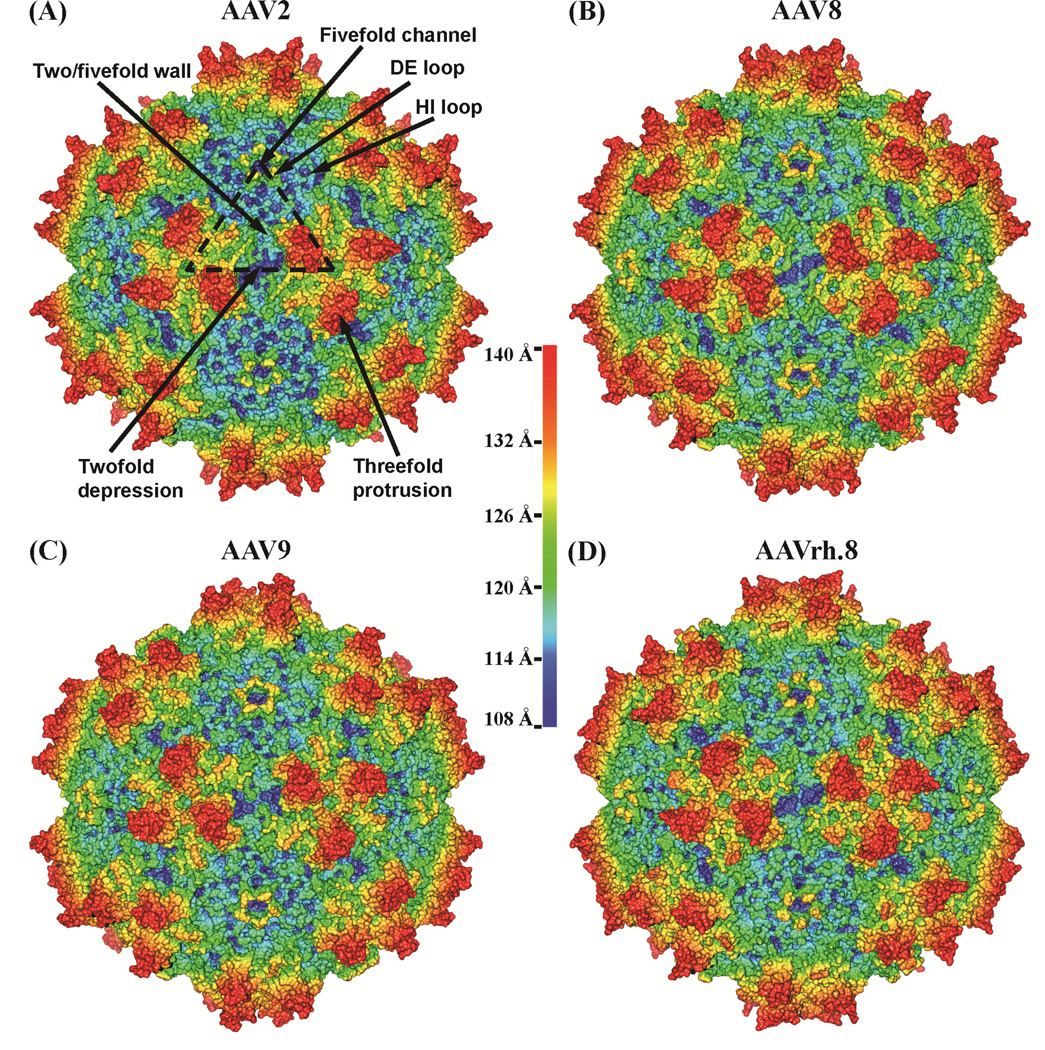

The ordered AAVrh.8 VP3 structure exhibited the AAV structural topology, which includes the eight-stranded (βBIDG and βCHEF sheets) antiparallel β-barrel motif (common in most virus structures), with loop insertions between the β-strands, an α-helix (αA: residues 294–304; VP1 numbering), and an additional β-strand, βA, involved in antiparallel interactions with βB (Fig 2B). The loops are named after the β-strands that they connect and contain small stretches of antiparallel β-strands and helical structures, as previously described for other parvoviruses (reviewed in (Chapman and Agbandje-McKenna, 2006; Halder et al., 2012a)). The β-barrel represents ~16% of the ordered VP3 sequence and forms the core of the capsid with the βBIDG sheet forming the interior capsid surface. The loops connecting the β-barrel strands cluster with the icosahedral symmetry-related VP3 monomers to form the characteristic capsid surface features at and around the icosahedral two-, three- and five-fold axes of symmetry. These include a depression at the twofold axis, three protrusions surrounding the depression at the threefold axis, a depression surrounding the protruding cylindrical channel at the fivefold axis, and a ‘wall’ between the two- and fivefold depressions (the two/fivefold wall) (Fig. 3). The floor of the twofold axis is the thinnest region of the capsid created by the intertwining of the loop after βI (residues 693–707; VP1 numbering) from two twofold symmetry-related monomers, thus, resulting in the least number of inter-monomer interactions. The conserved αA forms the floor of the depression at the twofold axis, and the walls are formed by amino acid stretches 527–535, 559–564, and 723–733 at the C-terminus. Each of the three separate protrusions surrounding the threefold axis is formed by the intertwining of three loop regions (within the GH loop between strands βG and βH) from two threefold symmetry-related VP3 monomers. Residues 442–466 and 578–595 from one VP3 monomer, stabilized by small β-strands form the two fingerlike protrusions and flank the residues 484–509 from the other threefold symmetry-related monomer to form the protrusion. Residues 544–557 form the shoulder of the threefold protrusions. Two small stretches of antiparallel strand structure between βD and βE form a β-ribbon (DE loop; residues 322–338) that icosahedrally cluster to form the lining of the cylindrical channel at the fivefold axis (Fig. 2B and Fig. 3). The floor of the depression around this channel is lined by the loop between βH and βI (HI loop; residues 654–671) that extends over residues 246–252, 362–375, and 677–674 of an adjacent fivefold symmetry-related monomer (Fig. 2B and Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Capsid surface comparison of AAV structures. (A–D) are AAV2, AAV8, AAV9, and AAVrh.8, respectively. The capsid surfaces are shown radially color-cued (from capsid center to surface: blue-green-yellow-red) with radii shown in the color palette. The surface features for AAV capsids: twofold depression, threefold protrusion, fivefold channel, two/fivefold wall, DE loop, and HI loop are indicated on the AAV2 capsid surface. This figure was generated using UCSF-Chimera (Pettersen et al., 2004).

Positive density in the averaged Fo-Fc map (at σ>3.0) was observed inside the channel at the icosahedral fivefold axis of the capsid and could be modeled as a stretch of 7 Gly/Ala residues (possibly residues 204–210 based on the fit into density) (Fig. 2C and D). The observation of density within the fivefold channel and extending into the capsid interior has been previously reported for other parvoviruses, including AAVs (AAV8, AAV9, and AAVrh32.33) and the autonomous parvoviruses (minute virus of mice and canine parvovirus) (Agbandje-McKenna et al., 1998; DiMattia et al., 2012; Mikals et al., 2014; Nam et al., 2007; Xie and Chapman, 1996). Combined with biochemical data, this observation supports the speculation that the phospholipase A2 domain within VP1u and VP1/VP2 nuclear localization signals are externalized through the fivefold channel (Bleker et al., 2005; Grieger et al., 2006; Kronenberg et al., 2005; Sonntag et al., 2006). However, unlike the observation for the AAV8 crystal structure, where weak density (2Fo-Fc ~ 0.5σ, Fo-Fc ~ 2.0σ) extending from residue 218 could be modeled as additional N-terminal residues that connect with the density in the channel or extend between the interfaces of the fivefold symmetry-related VP monomers towards the twofold axis (Nam et al., 2007), the AAVrh.8 density did not connect to residue 218 nor extend inside the capsid between the interfaces of the fivefold related VPs.

Structural comparison of AAVrh.8 to other AAV capsid structures

It has been demonstrated previously that serotype-specific sequences and capsid surface VRs primarily dictate receptor attachment, transduction efficiency, and antigenic properties for each AAV serotype (reviewed in (Agbandje-McKenna and Chapman, 2006; Agbandje-McKenna and Kleinschmidt, 2011; Govindasamy et al., 2006; Halder et al., 2012a; Tseng and Agbandje-McKenna, 2014)). Thus, to begin to delineate the sequence and structural differences of AAVrh.8 which may contribute to its phenotypic properties, its structure was compared to that of AAV2, AAV8, and AAV9 which have functional differences as well as similarities. AAV2, with a broad tissue tropism, is the most functionally characterized serotype; AAV8, which is liver tropic, shares the highest VP sequence identity with AAVrh.8; and AAV9 is phenotypically similar to AAVrh.8 in terms of its ability to cross the BBB and transduce neuronal cells.

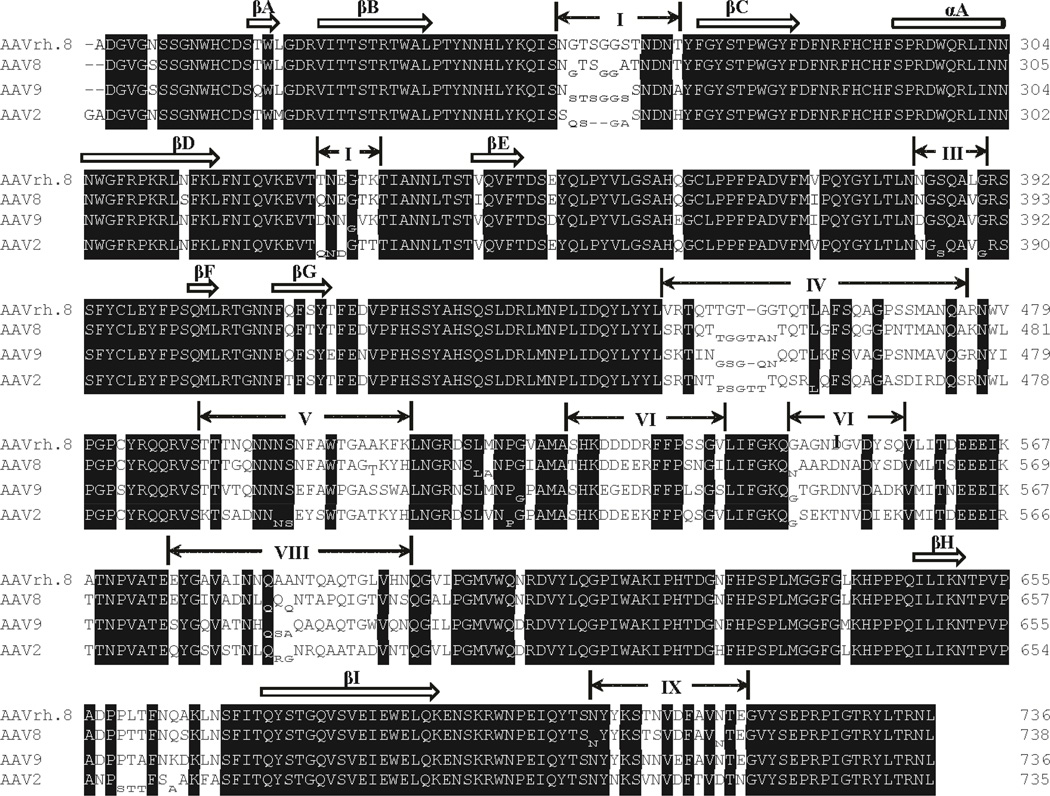

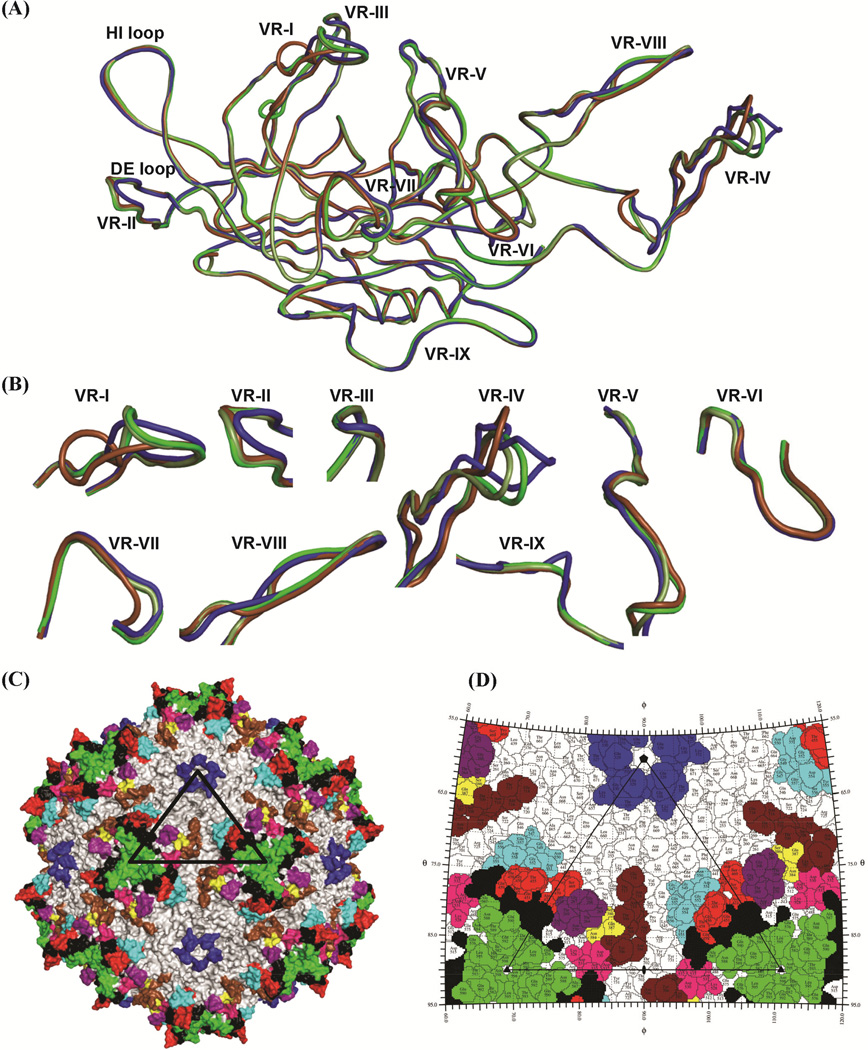

The structural alignment of AAVrh.8 VP3 with the VP3 for AAV2, AAV8, and AAV9 showed that the core β-barrel and α-helix are conserved, and also highlighted differences within the residues of the previously defined VRs (I-IX) (Govindasamy et al., 2006) (Fig. 4, Fig. 5A, B, and Table 2). AAVrh.8 shares the highest VP3 sequence identity of 89% with AAV8 (Table 2). The structurally ordered VP3 Cα positions of AAV2, AAV8, and AAV9 superposed onto AAVrh.8 with an overall R.M.S.D of 0.43–0.58 Å, secondary structure match of 81–94%, and Cα alignment of ~98–99%. The lowest sequence identity is with AAV2. However, overall these structures are very similar (Fig. 5A). It is likely that the conserved structural elements contribute to core functions such as capsid assembly and genome packaging while the surface VRs facilitate specific interactions with cell surface receptors, intracellular factors, or antibodies.

Figure 4.

Structure-based sequence alignment AAV VP3s. The alignment of the structurally ordered VP3 regions of AAVrh.8, AAV8, AAV9, and AAV2 are shown. Identical residues are shown in white text with a black background. The core β strands and the conserved a-helix regions are indicated as open arrows and a tube, respectively, above the alignment. The boundaries for the VRs are indicated by arrows and labeled. Amino acids in the VP regions that differ structurally (Cα R.M.S.D ≥1 Å) from AAVrh.8 are offset below the alignment.

Figure 5.

Comparison of AAV structures. (A) Superposition of coil representations of the VP3 of AAVrh.8 (dark green), AAV2 (blue), AAV8 (light green), and AAV9 (brown). The VRs are as labeled. (B) A close-up view of the VRs. (C) Surface representation of AAVrh.8 capsid with the VRs colored as: VR-I (purple), VR-II (blue), VR-III (yellow), VR-IV (red), VR-V (black), VR-VI (pink), VR-VII (cyan), VR-VIII (green), and VR-IX (brown). (D) Stereographic Roadmap projection of the AAVrh.8 capsid viewed down the twofold axis. Residues are labeled by type (three letter code) and number (AAVrh.8 VP1 numbering). The boundary for each residue is shown in black. The amino acid residues that are exposed on the capsid exterior are visible in this image. VR residues are colored as in (C). The viral asymmetric unit, bounded by a fivefold and two threefolds (connected by a twofold), is shown as a black triangle in (C) and (D). Panels A, B and C were generated using the PyMol program (DeLano, 2002) while panel D was generated using the RIVEM program (Xiao and Rossmann, 2007).

Table 2.

Cα positional variation of AAVrh.8 compared to other AAV VP3s

| Virus | % Identity | Maximum R.M.S.D in Cα position between AAVrh.8 and other AAVs in VR regions (Å) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | VR-I | VR-II | VR-III | VR-IV | VR-V | VR-VI | VR-VII | VR-VIII | VR-IX | ||

| AAV2 | 84a(81)b(98.5)c | 0.58 | 1.8–5.3 | 1.1–1.5 | 1.0 | 1.1–4.2 | 1.1–1.3 | <1.0 | 1.0 | 1.2–1.4 | <1.0 |

| AAV8 | 89a(88)b(99.6)c | 0.43 | 1.2–1.3 | <1.0 | <1.0 | 1.1–3.2 | 1.0 | <1.0 | 1.2 | 1.0–1.2 | 1.0–1.2 |

| AAV9 | 86a(94)b(98.4)c | 0.51 | 1.5–10.5 | 1.2 | <1.0 | 1.0–5.3 | <1.0 | <1.0 | 1.2 | 1.0–1.2 | <1.0 |

Values are for VP3 sequence identity

Values are for the match VP3 secondary structure

Values are for percentage of Cα positions aligned in the ordered VP3 structure

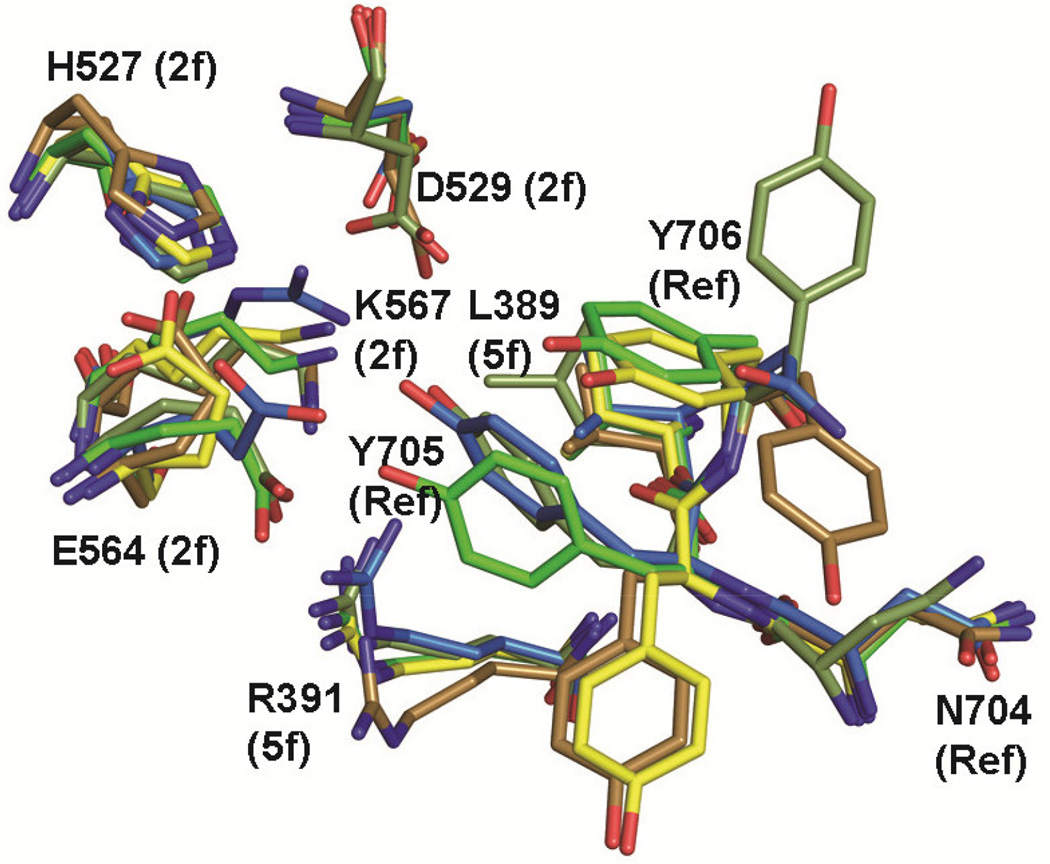

For all the viruses compared, the largest conformational differences to AAVrh.8 are localized within VR-I and VR-IV, with a difference in Cα of up to ~10 and ~5 Å, respectively, with AAV9 (Fig. 5B and Table 2). The Cα differences at the other previously defined VRs were minor (Table 2). The residue ranges comprising these VRs are listed in Table 3. Variable regions VR-I, VR-III, and VR-VII form the surface of the two/fivefold wall; VR-VI forms the wall of the depression at the twofold axis, and VR-IX forms the surface of the two/fivefold wall but also extends into the twofold depression; VR-IV, VR-V, and VR-VIII comprise the protrusion surrounding the threefold axis of symmetry; and VR-II forms the top of the fivefold channel (Fig. 5A, C, and D). Amino acid insertions/deletions contribute to the large conformational differences in VR-I and VR-IV, although for AAV9, with the largest difference in VR-1, there are no insertions/deletions in this region relative to AAVrh.8 (Fig. 4, Fig. 5A, B, and Table 2). In most of the VRs, the sequence composition is varied (Fig. 4), but even in regions where there is sequence conservation, some of the side-chain orientations were observed to vary, for example residues N704-Y706 in VR-IX (Fig. 6). In addition to differences in Cα distance, these variations in side-chain orientation contributed to the delineation of the VRs shown in Fig. 4. The clustering of the VRs on the assembled capsid resulted in local topological differences between the capsids compared, especially at the two/fivefold wall, the threefold protrusion, and the top of the fivefold channel (Fig. 3).

Table 3.

Variable region residue ranges based on comparison of AAV2, AAV8, AAV9, and AAVrh.8

| AAVrh.8/AAV9 | AAV2 | AAV8 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VR-I | 262–273 | 262–271 | 263–274 |

| VR-II | 327–332 | 325–330 | 328–333 |

| VR-III | 384–389 | 382–387 | 385–390 |

| VR-IV | 448–475 | 446–474 | 449–477 |

| VR-V | 491–510 | 490–509 | 493–512 |

| VR-VI | 526–540 | 525–539 | 528–542 |

| VR-VII | 547–557 | 546–556 | 549–559 |

| VR-VIII | 576–598 | 575–597 | 578–600 |

| VR-IX | 704–718 | 703–717 | 706–720 |

Figure 6.

The dynamic VR-IX. Residues 704–706 and neighboring residues are shown for AAVrh.8 (dark green), AAV8 at pH 7.5 (light green), AAV8 at pH 4.0 (yellow), AAV9 (brown), and AAV2 (blue). The AAVrh.8 residue positions are labeled. This figure was generated using the PyMol program (DeLano, 2002).

The largest variation between AAVrh.8 and AAV2 was at the top of the fivefold channel, formed by VR-II (Fig. 3, Fig. 5, and Table 2). Variations are observed at the apex of this loop (VR-II) when most parvovirus structures are compared, despite a conservation of the β-ribbon (DE loop) forming the channel (Fig. 4 and Fig. 5A). This is consistent with the dynamics required for the postulated genome packaging or externalization of VP1u and the N-terminus of VP2 function of the channel. The HI loop, surrounding the channel, is highly conserved among AAVrh.8, AAV2, AAV8, and AAV9 but shows more differences in sequence composition for AAV2 resulting in a minor structural difference (Fig. 3). The HI loop has been demonstrated to play a critical role in capsid assembly and DNA packaging (DiPrimio et al., 2008). Thus the conservation of this structural motif was anticipated.

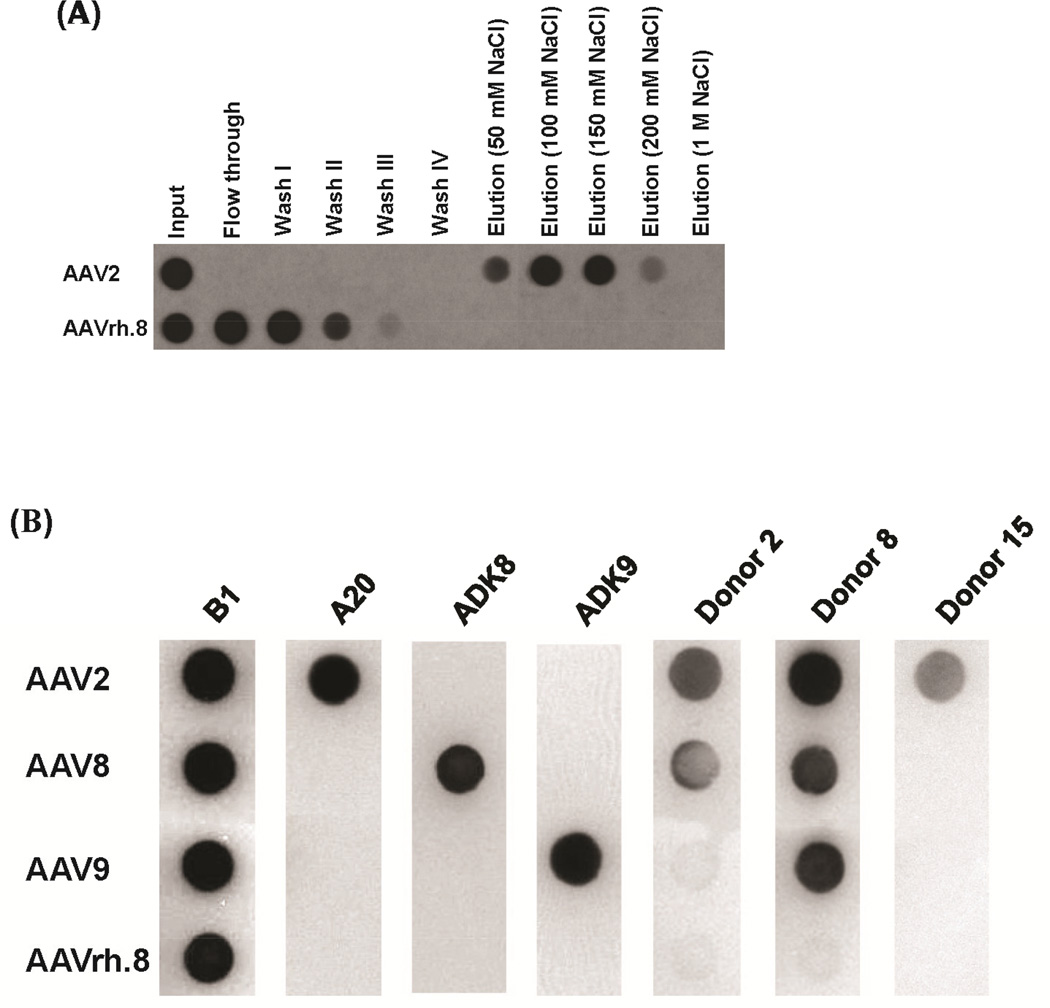

Comparison of AAVrh.8 to other AAVs points to functionally important regions

There is currently no information on the functional regions of the AAVrh.8 capsid. Thus a review of the functionally annotated regions of AAV2, AAV8, and AAV9 was conducted to determine potential overlaps with respect to receptor attachment, transduction determinants, and antigenic regions (Table 4). AAV2 binds HS as a primary glycan receptor and uses several secondary co-receptors, including integrins, for internalization (Asokan et al., 2006; Summerford and Samulski, 1998; Summerford et al., 1999). This serotype utilizes residues R484, R487, K532, R585, and R585 (Table 5) for HS recognition (Kern et al., 2003; Opie et al., 2003; Summerford and Samulski, 1998). These residues are located in VR-V, VR-VI, and VR-VIII and cluster at the inner wall of the threefold protrusions. Residues R484, R487, and K532 are conserved in the AAVrh.8 as R485, R488, and R533 (and also in AAV8 and AAV9) but not the R585 and R588 (A586 and T589 in AAVrh.8) which are the most critical for AAV2’s HS binding. The AAV3b, AAV6 or AAV13 HS binding site residues (AAV3b: R594; AAV6: K531, K459, K493, R576; and AAV13: K528 (Table 5)) (Handa et al., 2000; Lerch and Chapman, 2012; Rabinowitz et al., 2002; Schmidt et al., 2008b; Wu et al., 2006; Xie et al., 2011) are also not conserved in AAVrh.8. AAV8 and AAV9 do not bind HS, thus the prediction was that AAVrh.8 is not capable of this interaction. This was confirmed by the heparin column elution profile of AAVrh.8 (Fig. 7A). While AAV2 was able to bind to the heparin column and was eluted with increasing salt concentration, AAVrh.8 was observed in the flow through and wash fractions. Thus this serotype is not likely to utilize HS as a cellular attachment receptor. However, with respect to co-receptor attachment, the 512NGR514 motif, reported to play a role in the recognition of an α5β1 integrin co-receptor by AAV2 (Asokan et al., 2006) and AAV9 (Shen et al., 2015) is conserved in AAVrh.8. This motif is located at the edge of VR-V and is situated close to the base of the threefold protrusions or the two/fivefold wall. A potential role for this motif in receptor recognition by AAVrh.8 remains to be verified.

Table 4.

Known function(s) of AAV variable regions

Table 5.

Residues known to be involved in HS and galactose interactions for AAV serotypes

| Heparin Binding | |

|---|---|

| AAV2 | R484 (R485*), R487 (R488), K532 (R533), R585 (A586), R588 (T589) |

| AAV3b | R594 (G594) |

| AAV6/ AAV13 |

K531 (D531), K459 (Q459), K493 (T493), R576 (E576) |

| Galactose binding | |

| AAV9 | D271 (D271), N272 (N272), Y446 (Y446), N470 (S470), W503 (W503) |

Figure 7.

AAVrh.8 heparin binding assay and antigenic reactivity. (A) The heparin binding profile of AAV2 (positive control) and AAVrh.8. The elution fractions at 250- 900 mM NaCl are not shown. Virus in the input, flow through, washes and elutions were detected by denatured dot blot using the B1 MAb. (B) Dot blot of AAV2, AAV8, AAV9 and AAVrh.8 against different MAbs or human donor sera; B1 (linear epitope on AAVs), A20 (anti-AAV2), ADK8 (anti-AAV8), ADK9 (anti-AAV9), donor 2, donor 8, and donor 15 (commercially available samples). The black dots indicate a positive response.

AAV8 was shown to utilize the 37/67 kDa laminin receptor (LamR) as a co-receptor (Akache et al., 2006) and because it is also reported to be used by AAV2, AAV3, and AAV9, the possibility remains that it could be utilized by AAVrh.8. The binding site for LamR on the AAV8 capsid was mapped to two large peptide regions containing residues 489–545 and 591–621 within the GH loop (AAVrh.8, VP1 numbering) (Akache et al., 2006). These residues are located on the inner surface of the AAV8 threefold protrusions facing the threefold axis (Nam et al., 2007) and include residues in VR-V and VR-VI for the first stretch of amino acids and residues in VR-VIII and conserved amino acids located before the βH strand for the second stretch. While there are residue-level differences, loop structures at these VRs are similar for AAV2, AAVrh.8, AAV8, and AAV9 (Fig. 5A, B, and Table 2). Thus it is possible that the capsid region/surface features around the threefold axis rather than the specific sequence dictates the LamR recognition, or that the second stretch of residues that is conserved in sequence and structure and located closer to the threefold axis may be more important for this recognition.

For AAV9, reported to bind galactose as a primary receptor, this binding site has been mapped to residues D271 (VR-I), N272 (VR-I), Y446 (VR-IV), N470 (VR-IV), and W503 (VR-V) (Table 5) which form a pocket at the base of the threefold protrusion facing the fivefold axis (Bell et al., 2012). All these residues are conserved in AAVrh.8 except for N470 (S470 in AAVrh.8) which is the most critical for AAV9’s galactose binding and also distinguishes it from other AAVs. Thus it is not anticipated that AAVrh.8 will utilize terminal galactose as a primary cellular attachment receptor. Another glycan reported to be engaged by AAVs for attachment is sialic acid. The critical residues used by AAV4 and AAV5 for this interaction are not present in AAVrh.8 (reviewed in (Huang et al., 2014), (Afione et al., 2015; Shen et al., 2013)). Thus the glycan utilized as a primary receptor by AAVrh.8 (if any) and the capsid region involved in cellular attachment remains to be determined.

The characterizations of the binding sites for a number of neutralizing antibodies against the AAV2 and AAV8 capsids have been reported. For AAV2, the binding site for MAbs A20 and C37-B were determined by cryo-reconstruction following site-directed mutagenesis and peptide scanning analysis (Gurda et al., 2013; Lochrie et al., 2006; McCraw et al., 2012; Wobus et al., 2000). The A20 footprint covers a large area of the capsid and includes residues in VR-I, VR-III, VR-VII, and VR-IX and the HI-Loop (Lochrie et al., 2006; McCraw et al., 2012). The C37-B epitope, determined by peptide scanning analysis and cryo-reconstruction includes residues in VR-V and VR-VIII (Gurda et al., 2013; Wobus et al., 2000). AAV2 and AAVrh.8 display structural and sequence differences in all these VRs. For AAV8, the ADK8 footprint covered residues in VR-IV, VR-V, and VR-VIII, but only the VR-VIII residues were important for neutralization (Gurda et al., 2012). AAVrh.8 displays only minor main-chain differences (1.0–1.2 Å in Cα positions) to AAV8 in VR-VIII, but the two viruses differ at the residue level (Fig. 4). For AAV9, while several MAbs now exist ((Sonntag et al., 2011) and unpublished data), there is no epitope information available, but the prediction is that these will recognize the VRs given the reports for the other AAVs. Thus it was predicted that MAbs raised against AAV2, AAV8, and AAV9 capsids will not cross-react with the AAVrh.8 capsid. This was confirmed by an antibody cross-reactivity assay with MAbs reported to be specific against these three serotypes: A20 (anti-AAV2), ADK8 (anti-AAV8), and ADK9 (anti-AAV9) (Fig. 7B). In addition, a screen of capsid reactivity against human donor serum showed a positive response against AAV2 for all three samples tested. AAV8 showed a positive against two of the samples while AAV9 showed a response against one of the samples (Fig. 7B). These assays thus identified regions of the AAVrh.8 capsid capable of escaping antibody recognition and indicate a low immune prevalence to AAVrh8 in the human population. Neutralizing antibodies to other non-human primates, for example AAVrh32.33 also exist in very low levels in the human population (Calcedo et al., 2009).

Several regions of the capsid, mostly localized to the VRs discussed above, have also been reported as being involved in transduction determination for AAV2, AAV8, and AAV9 (Table 4). Given the phenotypic similarity in the ability of AAVrh.8 and AAV9 to cross the BBB and transduce neuronal cells, residues involved in AAV9 transduction properties were compared, although a neurotropic determinant is unknown for this serotype. Mutagenesis studies have identified residues N498, W503, and P504, and Q590 in VR-V and VR-VIII, respectively, to affect liver and muscle-specific transduction in AAV9 (Pulicherla et al., 2011) and all these residues except P504 are conserved in AAVrh.8, AAV8, and AAV2 (T504 in AAVrh.8; T506 in AAV8 and T503 in AAV2). The same region was reported to contribute to liver and cardiac specific transduction (Adachi et al., 2014). Another study identified residues in VR-IV and VR-VII as determinants of AAV9’s increased liver transduction efficiency compared to AAV1 and delayed blood clearance compared to AAV1, AAV2, and AAV8 (Kotchey et al., 2011). This phenomenon was proposed to maintain infectivity in the bloodstream and facilitate enhanced cardiac transduction by AAV9. The same study identified residues in AAV9 VR-IX as determinants of heart tropism. In yet another study, mutagenesis identified AAV9 residue Y706, also in VR-IX, as the determinant of improved melanoma tropism in a chimeric virus, chimera-1829, created by DNA shuffling approaches from AAV1, AAV8, AAV2, and AAV9 (Li et al., 2008). AAVrh.8 and AAV9 show large structural differences in VR-IV, and side-chain conformation differences in VR-V, VR-VII, VR-VIII, and VR-IX. This observation and the data in Table 4 (for all the serotypes compared) support overlapping transduction functions for these VRs, but the variations in structure suggest capsid-specific interactions.

Interestingly, while residues 704–706 in VR-IX, located adjacent to the twofold axis (Fig. 5C and D), are conserved between AAVrh.8, AAV2, AAV8, and AAV9 (except for AAV2 which has an Asn instead of Tyr at position 705) (Fig. 4), and the VP3 backbone is structurally conserved, the side-chain conformations are very dynamic (Fig. 6). AAVrh.8 Y705 adopts a conformation which is different from AAV9 and the structurally equivalent Y707 in AAV8 (Fig. 6). These side-chain conformational differences result in differences in interactions with neighboring residues such as L389, R391, H527, D529, E564, and K567 (Fig. 6). Interestingly, AAV8 Y707 and adjacent residues are involved in pH-mediated structural transitions predicted to occur during virus trafficking through the endocytic pathway (Nam et al., 2011), and E563A and H526A mutations in AAV2 (equivalent to E564 and H527 in AAVrh.8) showed severe defect in infectivity (Lochrie et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2000). Other studies with AAV2 have shown that an E563A mutation eliminates a novel capsid protease activity (Salganik et al., 2012), and Y704A (equivalent to AAVrh.8 Y705) plays a role in second-strand synthesis and transcription of the input genome (Salganik et al., 2014). AAV2 Y704 is also part of a series of tyrosines which when mutated to phenylalanines resulted in improved intracellular trafficking to the nucleus and hence increase in transduction efficiency dependent on the cell line (Zhong et al., 2008). Furthermore, restraining the two-fold interface by the formation of dityrosine adducts involving Y704 in AAV2 results in decreased transduction efficiency and also hinders the externalization of VP N-termini (Horowitz et al., 2012). AAVrh.8 residue Y706, adjacent to Y705, also adopts a different conformation compared to the tyrosine in the other AAVs compared, oriented away from the twofold interface (Fig. 6). These examples highlight the importance of the residues at the twofold region as transduction determinants. The possibility of similar functions for these residues in AAVrh.8 remains to be tested.

In addition to the side-chain differences observed in the AAV VRs, several conserved residues in the capsid interior, for example R312, K316, and Q412 (located in the BIDG sheet), and K689 located at the twofold interface, adopt conformations that are different from two or all the AAVs compared. Specific functions have not been reported for these residues.

The examples highlighted for regions of the AAV capsid utilized for receptor attachment, as transduction determinants, and antigenic footprints (Table 4), combined with the structural differences in the AAVrh.8 compared to AAV2, AAV8, and AAV9 (Fig. 3, 4, 5, 6, and Tables 2 and 3) show a concentration of functional determinants on the VRs. Thus we postulate that regions of VRs that did not differ significantly between AAVrh.8 and AAV9, such as VR-V and VR-IX, could be responsible for their common property of increased transduction efficiency in neuronal cells. It is also possible that they utilize a common VR(s) with a structural difference (to be determined) but engage in virus-specific host interactions to facilitate this function.

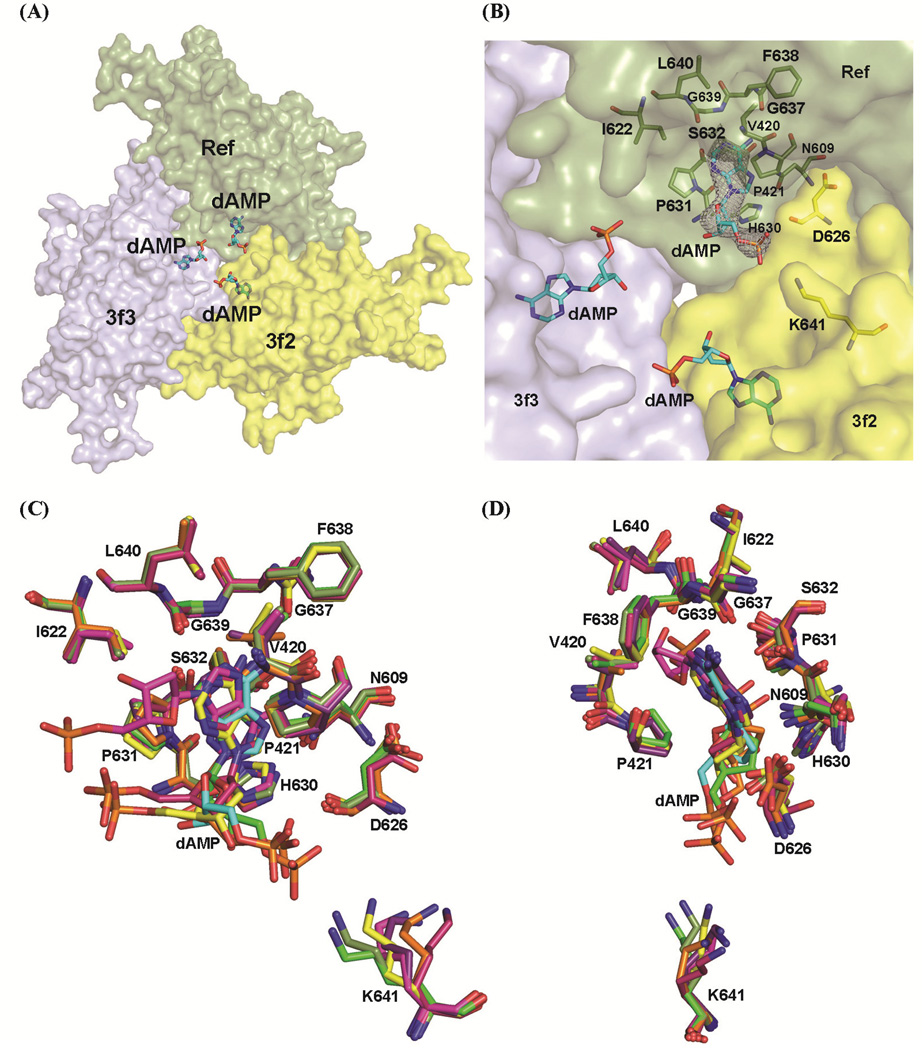

The conserved AAV DNA binding pocket

Electron density for a single purine NT was clearly observed in the capsid interior close to the threefold axis in a previously identified AAV DNA binding pocket (Fig. 8) (Govindasamy et al., 2006; Lerch et al., 2010; Mikals et al., 2014; Nam et al., 2011; Nam et al., 2007; Ng et al., 2010). The density threshold (Fo-Fc ~5.0σ; 2Fo-Fc ~1.5σ) for the base, which inserts itself into the capsid, was higher than that for the deoxyribose sugar (Fo-Fc ~4.0σ; 2Fo-Fc ~1.0σ) and the phosphate group (Fo-Fc ~3.5σ; 2Fo-Fc ~0.8σ). The base was modeled as a purine consistent with the size of the density and it could be modeled as either adenine or guanine (positive Fo-Fc density at 2.0σ observed around the C2 position for amino group; average B-factors of 75 Å2 for AMP versus 82 Å2 for GMP). Due to the icosahedral averaging applied during structure determination, it is possible that the density represents a symmetry averaged mixture with a small proportion of other base types. The binding site consists of residues V420, P421, N609, I622, H630, P631, S632, G637, F638, G639, and L640 from one VP3, and residues D626 and K641 from a threefold related VP3 (Table 6). These residues participate in non-specific (with deoxyribose sugar and phosphate) and specific (with base) hydrophobic and polar interactions with the NT (Table 6).

Figure 8.

AAVrh.8 NT binding site. (A) Surface representation of a trimer showing the inside surface of the capsid with the NT (dAMP) shown in stick model (C in cyan, N in blue, O in red, and phosphate group in orange). The threefold symmetry related monomers interacting with the NT are labeled (3f2, 3f3). (B) A close-up of the NT binding pocket. The NT is shown inside the 2Fo-Fc electron density map (gray mesh) contoured at threshold of 1.0 σ. The residues in the Ref and threefold symmetry related monomers (3f2, 3f3) that interact with the NT are depicted as a stick model and labeled. (C) Superposition of the AAVrh.8 (dark green) NT binding site with that of AAV1 (purple), AAV3b (yellow), AAV4 (red), AAV6 (hot pink), AAV8 (light green), and AAVrh32.33 (orange). (D) Another view of the conserved NT binding pocket rotated relative to panel (C) for better visualization of the residues forming the binding pocket. This figure was generated using the PyMol program (DeLano, 2002).

Table 6.

AAVrh.8 VP3-NT interaction

| AAV Serotypes | AAVrh.8 VP atom (Ref) |

NT atom | Dist (Å) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3b | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 9 | rh32.33 | AMP/GMP | ||

| V | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | V | V420 (CG2) | N1 | 3.6/3.7 |

| P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P421 (CG) | C5 | 4.1/4.2 |

| D | D | D | N | E | D | N | D | N | N609 (ND2) | N7 | 3.8/3.6 |

| I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I622 (CD1) | C2/N2 | 4.5/3.7 |

| H | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | H | H630 (ND1)/(CE1) |

C2’/C8 | 3.2/3.1 |

| P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P631 (O) | C2 | 3.3/3.4 |

| S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S632 (OG) | N6/O6 | 3.3/3.1 |

| G | G | G | G | G | G | G | G | G | G637 (O) | N6/O6 | 3.7/3.6 |

| F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F | F638 (CA) | N6/O6 | 3.8/3.9 |

| G | G | G | G | G | G | G | G | G | G639 (O) | C2/N2 | 3.1/2.3 |

| L | L | L | L | L | L | L | L | L | L640 (N) | −/N2 | −/4.4 |

| VP atom (3f) | |||||||||||

| D | D | D | D | G | D | D | D | D | D626 (O) | OP2/C8 | 3.9/4.4 |

| K | K | K | K | K | K | K | K | K | K641 (NZ) | OP1 | 4.0/4.2 |

A NT has been observed in the same location for AAV1, AAV3b, AAV4, AAV6, AAV8, and AAVrh32.33 structures but not for AAV2, AAV5, and AAV9 although the binding site is highly conserved in all AAV serotypes (Table 6). Where a NT is observed, the base is located in the same capsid interior position while the orientations of the deoxyribose and phosphate groups differ. The conserved location of the base and its higher sigma threshold compared to the sugar and phosphate groups suggests that specific VP-base interactions dictate the ordering of the nucleotide. As has been discussed in previous reports, the ordering of a NT is unusual because the AAVs package only a single copy of either the negative or positive sense strand of the genome, so the crystal contains two different populations of capsids and also the structure determination procedure assumes icosahedral symmetry (i.e. 60 equivalent positions). A lower occupancy, 0.7 relative to the VP3 amino acids was used for the refinement of the NT to achieve acceptable temperature factors for its atoms (~74.7 Å2). This is likely due to all 60 VP3 sites not being occupied consistent with the expected lack of icosahedral symmetry for NTs ordered within capsids. Similar occupancy levels were utilized during the refinement of the ordered NT in other AAV capsid structures (Govindasamy et al., 2006; Lerch et al., 2010; Mikals et al., 2014; Nam et al., 2011; Ng et al., 2010).

Interestingly, the high conservation in sequence and structure of the NT binding site residues in all AAV serotypes suggests a functional importance for this interaction in the viral life cycle, such as a role in capsid/DNA stabilization or genome packaging or capsid assembly. The fact that a similar NT is observed in AAV capsids containing different DNA sequences such as wild type, GFP, luciferase, baculovirus or insect cell DNA suggests that the conserved binding pocket dictates the NT ordering and not the genome sequence or structure as previously proposed (Ng et al., 2010). Further studies characterizing this VP-DNA interaction could aid efforts to improve vector packaging efficiency. However, this binding pocket is not conserved in the capsid structures of other parvoviruses that package only the negative sense strand of their genomes, and also the ordered NT observed in these structures is located in a different pocket (Agbandje-McKenna et al., 1998; Halder et al., 2013; Xie and Chapman, 1996). In addition, the NT observed in the AAVs constitutes a very small fraction (~1%) of the genome, and is lower than that observed for the autonomous parvoviruses (12–25%).

Summary

The structure of AAVrh.8, a non-human primate derived vector, was determined to provide a structural basis for its phenotypic properties. The structural differences observed between the closely related AAVrh.8, AAV8, and AAV9 visualize regions of the VP which can be probed using molecular and biochemical approaches to understand the mechanism of AAVrh.8’s enhanced neuronal transduction and antigenic differences. The observation of an ordered nucleotide in the previously identified conserved AAV DNA binding pocket suggests an important role for this interaction in virus infection. This structure will aid in the efforts to develop recombinant AAV vectors with improved transduction, specific tissue targeting, and ability to evade antibody immune responses.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff at the F1 beamline at CHESS, Cornell University, for help during data collection. We especially thank Kathy Dedrick at CHESS, for assistance in obtaining beam time. CHESS is supported by the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of General Medical Sciences under NSF award DMR-0936384, and the MacCHESS facility through award GM-103485 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health. This research was funded by NIH R01 GM082946 (to MAM and RM), NHLBI HHSN268201200041C (JMW) and P01HL059407-15 (JMW) and funds from the College of Medicine and McKnight Brain Institute (to MAM).

Abbreviations

- VP

Viral protein

- HS

Heparan sulfate

- VR

Variable region

- AAV

Adeno-associated virus

- ss

single-stranded

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- EM

electron microscopy

- NCS

non-crystallographic symmetry

- NT

nucleotide

- LamR

laminin receptor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Statement of Conflict: M. Agbandje-McKenna (MAM) is a SAB member for Voyager Therapeutics, Inc and has a sponsored research agreement with AGTC. Both companies have interest in the development of AAV for gene delivery applications. MAM is also an inventor of AAV patents licensed to various biopharmaceutical companies. J.M. Wilson is an advisor to REGENXBIO, Dimension Therapeutics, and Solid Gene Therapy, and is a founder of, holds equity in, and has a sponsored research agreement with REGENXBIO and Dimension Therapeutics; in addition, he is a consultant to several biopharmaceutical companies and is an inventor on patents licensed to various biopharmaceutical companies.

References

- Adachi K, Enoki T, Kawano Y, Veraz M, Nakai H. Drawing a high-resolution functional map of adeno-associated virus capsid by massively parallel sequencing. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3075. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afione S, DiMattia MA, Halder S, Di Pasquale G, Agbandje-McKenna M, Chiorini JA. Identification and mutagenesis of the adeno-associated virus 5 sialic A cid binding region. J Virol. 2015;89:1660–1672. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02503-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agbandje-McKenna M, Chapman MS. Correlating structure with function in viral capsid. In: Kerr JR, Cotmore SF, Bloom ME, Linden RM, Parrish CR, editors. Parvoviruses. London: Hodder Arnold; 2006. pp. 125–139. [Google Scholar]

- Agbandje-McKenna M, Kleinschmidt J. AAV capsid structure and cell interactions. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;807:47–92. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-370-7_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agbandje-McKenna M, Llamas-Saiz AL, Wang F, Tattersall P, Rossmann MG. Functional implications of the structure of the murine parvovirus, minute virus of mice. Structure. 1998;6:1369–1381. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00137-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akache B, Grimm D, Pandey K, Yant SR, Xu H, Kay MA. The 37/67-kilodalton laminin receptor is a receptor for adeno-associated virus serotypes 8, 2, 3, and 9. J Virol. 2006;80:9831–9836. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00878-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslanidi GV, Rivers AE, Ortiz L, Song L, Ling C, Govindasamy L, Van Vliet K, Tan M, Agbandje-McKenna M, Srivastava A. Optimization of the capsid of recombinant adeno-associated virus 2 (AAV2) vectors: the final threshold? PLoS One. 2013;8:e59142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asokan A, Hamra JB, Govindasamy L, Agbandje-McKenna M, Samulski RJ. Adeno-associated virus type 2 contains an integrin alpha5beta1 binding domain essential for viral cell entry. J Virol. 2006;80:8961–8969. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00843-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atchison RW, Casto BC, Hammon WM. Adenovirus-Associated Defective Virus Particles. Science. 1965;149:754–756. doi: 10.1126/science.149.3685.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bantel-Schaal U, zur Hausen H. Characterization of the DNA of a defective human parvovirus isolated from a genital site. Virology. 1984;134:52–63. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90271-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell CL, Gurda BL, Van Vliet K, Agbandje-McKenna M, Wilson JM. Identification of the galactose binding domain of the adeno-associated virus serotype 9 capsid. J Virol. 2012;86:7326–7333. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00448-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blacklow NR, Hoggan MD, Kapikian AZ, Austin JB, Rowe WP. Epidemiology of adenovirus-associated virus infection in a nursery population. Am J Epidemiol. 1968;88:368–378. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleker S, Sonntag F, Kleinschmidt JA. Mutational analysis of narrow pores at the fivefold symmetry axes of adeno-associated virus type 2 capsids reveals a dual role in genome packaging and activation of phospholipase A2 activity. J Virol. 2005;79:2528–2540. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.4.2528-2540.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutin S, Monteilhet V, Veron P, Leborgne C, Benveniste O, Montus MF, Masurier C. Prevalence of serum IgG and neutralizing factors against adeno-associated virus (AAV) types 1, 2, 5, 6, 8, and 9 in the healthy population: implications for gene therapy using AAV vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 2010;21:704–712. doi: 10.1089/hum.2009.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles DE, Rabinowitz JE, RJ S. The Genus Dependovirus. In: Kerr JR, Cotmore SF, Bloom ME, Linden RM, Parrish CR, editors. Parvoviruses. London: Hodder Arnold; 2006. pp. 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles DE, McPhee SW, Li C, Gray SJ, Samulski JJ, Camp AS, Li J, Wang B, Monahan PE, Rabinowitz JE, Grieger JC, Govindasamy L, Agbandje-McKenna M, Xiao X, Samulski RJ. Phase 1 gene therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy using a translational optimized AAV vector. Mol Ther. 2012;20:443–455. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger AT. Assessment of phase accuracy by cross validation: the free R value. Methods and applications. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1993;49:24–36. doi: 10.1107/S0907444992007352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kuns tleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buller RM, Rose JA. Characterization of adenovirus-associated virus-induced polypeptides in KB cells. J Virol. 1978;25:331–338. doi: 10.1128/jvi.25.1.331-338.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calcedo R, Vandenberghe LH, Gao G, Lin J, Wilson JM. Worldwide epidemiology of neutralizing antibodies to adeno-associated viruses. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:381–390. doi: 10.1086/595830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo-Tripp M, Shepherd CM, Borelli IA, Venkataraman S, Lander G, Natarajan P, Johnson JE, Brooks CL, 3rd, Reddy VS. VIPERdb2: an enhanced and web API enabled relational database for structural virology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D436–442. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter BJ. Adeno-associated Virus Vectors and Biology of Gene Delivery. In: Kerr JR, Cotmore SF, Bloom ME, Linden RM, Parrish CR, editors. Parvoviruses. London: Hodder Arnold; 2006. pp. 497–498. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman MS, Agbandje-McKenna M. Atomic structure of viral particles. In: Kerr JR, Cotmore SF, Bloom ME, Linden RM, Parrish CR, editors. Parvoviruses. London: Hodder Arnold; 2006. pp. 107–123. [Google Scholar]

- Chen VB, Arendall WB, 3rd, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotmore SF, Agbandje-McKenna M, Chiorini JA, Mukha DV, Pintel DJ, Qiu J, Soderlund-Venermo M, Tattersall P, Tijssen P, Gatherer D, Davison AJ. The family Parvoviridae. Arch Virol. 2014;159:1239–1247. doi: 10.1007/s00705-013-1914-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coura Rdos S, Nardi NB. The state of the art of adeno-associated virus-based vectors in gene therapy. Virol J. 2007;4:99. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-4-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daya S, Berns KI. Gene therapy using adeno-associated virus vectors. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:583–593. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00008-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphic System. San Carlos, CA: DeLano Scientific; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- DiMattia MA, Nam HJ, Van Vliet K, Mitchell M, Bennett A, Gurda BL, McKenna R, Olson NH, Sinkovits RS, Potter M, Byrne BJ, Aslanidi G, Zolotukhin S, Muzyczka N, Baker TS, Agbandje-McKenna M. Structural insight into the unique properties of adeno-associated virus serotype 9. J Virol. 2012;86:6947–6958. doi: 10.1128/JVI.07232-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPrimio N, Asokan A, Govindasamy L, Agbandje-McKenna M, Samulski RJ. Surface loop dynamics in adeno-associated virus capsid assembly. J Virol. 2008;82:5178–5189. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02721-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flotte TR, Carter BJ. Adeno-associated virus vectors for gene therapy. Gene Ther. 1995;2:357–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foust KD, Nurre E, Montgomery CL, Hernandez A, Chan CM, Kaspar BK. Intravascular AAV9 preferentially targets neonatal neurons and adult astrocytes. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G, Vandenberghe LH, Alvira MR, Lu Y, Calcedo R, Zhou X, Wilson JM. Clades of Adeno-associated viruses are widely disseminated in human tissues. J Virol. 2004;78:6381–6388. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.12.6381-6388.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao GP, Alvira MR, Wang L, Calcedo R, Johnston J, Wilson JM. Novel adeno-associated viruses from rhesus monkeys as vectors for human gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11854–11859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182412299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georg-Fries B, Biederlack S, Wolf J, zur Hausen H. Analysis of proteins, helper dependence, and seroepidemiology of a new human parvovirus. Virology. 1984;134:64–71. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90272-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giove TJ, Sena-Esteves M, Eldred WD. Transduction of the inner mouse retina using AAVrh8 and AAVrh10 via intravitreal injection. Exp Eye Res. 2010;91:652–659. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girod A, Ried M, Wobus C, Lahm H, Leike K, Kleinschmidt J, Deleage G, Hallek M. Genetic capsid modifications allow efficient re-targeting of adeno-associated virus type 2. Nat Med. 1999;5:1052–1056. doi: 10.1038/12491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindasamy L, Padron E, McKenna R, Muzyczka N, Kaludov N, Chiorini JA, Agbandje-McKenna M. Structurally mapping the diverse phenotype of adeno-associated virus serotype 4. J Virol. 2006;80:11556–11570. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01536-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindasamy L, DiMattia MA, Gurda BL, Halder S, McKenna R, Chiorini JA, Muzyczka N, Zolotukhin S, Agbandje-McKenna M. Structural insights into adeno-associated virus serotype 5. J Virol. 2013;87:11187–11199. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00867-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieger JC, Snowdy S, Samulski RJ. Separate basic region motifs within the adeno-associated virus capsid proteins are essential for infectivity and assembly. J Virol. 2006;80:5199–5210. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02723-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurda BL, Raupp C, Popa-Wagner R, Naumer M, Olson NH, Ng R, McKenna R, Baker TS, Kleinschmidt JA, Agbandje-McKenna M. Mapping a neutralizing epitope onto the capsid of adeno-associated virus serotype 8. J Virol. 2012;86:7739–7751. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00218-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurda BL, DiMattia MA, Miller EB, Bennett A, McKenna R, Weichert WS, Nelson CD, Chen WJ, Muzyczka N, Olson NH, Sinkovits RS, Chiorini JA, Zolotutkhin S, Kozyreva OG, Samulski RJ, Baker TS, Parrish CR, Agbandje-McKenna M. Capsid antibodies to different adeno-associated virus serotypes bind common regions. J Virol. 2013;87:9111–9124. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00622-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder S, Ng R, Agbandje-McKenna M. Parvoviruses: structure and infection. Future Virology. 2012a;7:253–278. [Google Scholar]

- Halder S, Nam H-J, Govindasamy L, Vogel M, Dinsart C, Salome N, McKenna R, Agbandje-McKenna M. Production, purification, crystallization and structure determination of H-1 Parvovirus. Acta Crystallographica Section F. 2012b;68:1571–1576. doi: 10.1107/S1744309112045563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder S, Nam HJ, Govindasamy L, Vogel M, Dinsart C, Salome N, McKenna R, Agbandje-McKenna M. Structural characterization of H-1 parvovirus: comparison of infectious virions to empty capsids. J Virol. 2013;87:5128–5140. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03416-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handa A, Muramatsu S, Qiu J, Mizukami H, Brown KE. Adeno-associated virus (AAV)-3-based vectors transduce haematopoietic cells not susceptible to transduction with AAV-2-based vectors. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:2077–2084. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-8-2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoggan MD, Blacklow NR, Rowe WP. Studies of small DNA viruses found in various adenovirus preparations: physical, biological, and immunological characteristics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1966;55:1467–1474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.55.6.1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz ED, Finn MG, Asokan A. Tyrosine cross-linking reveals interfacial dynamics in adeno-associated viral capsids during infection. ACS Chem Biol. 2012;7:1059–1066. doi: 10.1021/cb3000265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu C, Busuttil RW, Lipshutz GS. RH10 provides superior transgene expression in mice when compared with natural AAV serotypes for neonatal gene therapy. J Gene Med. 2010;12:766–778. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang LY, Halder S, Agbandje-McKenna M. Parvovirus glycan interactions. Curr Opin Virol. 2014;7:108–118. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttner NA, Girod A, Perabo L, Edbauer D, Kleinschmidt JA, Buning H, Hallek M. Genetic modifications of the adeno-associated virus type 2 capsid reduce the affinity and the neutralizing effects of human serum antibodies. Gene Ther. 2003;10:2139–2147. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson FB, Ozer HL, Hoggan MD. Structural proteins of adenovirus-associated virus type 3. J Virol. 1971;8:860–863. doi: 10.1128/jvi.8.6.860-863.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern A, Schmidt K, Leder C, Muller OJ, Wobus CE, Bettinger K, Von der Lieth CW, King JA, Kleinschmidt JA. Identification of a heparin-binding motif on adeno-associated virus type 2 capsids. J Virol. 2003;77:11072–11081. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.20.11072-11081.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleywegt GJ, Jones TA. Model building and refinement practice. Methods Enzymol. 1997;277:208–230. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)77013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koerber JT, Jang JH, Schaffer DV. DNA shuffling of adeno-associated virus yields functionally diverse viral progeny. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1703–1709. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotchey NM, Adachi K, Zahid M, Inagaki K, Charan R, Parker RS, Nakai H. A potential role of distinctively delayed blood clearance of recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 9 in robust cardiac transduction. Mol Ther. 2011;19:1079–1089. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krissinel E, Henrick K. Secondary-structure matching (SSM), a new tool for fast protein structure alignment in three dimensions. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2256–2268. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904026460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronenberg S, Kleinschmidt JA, Bottcher B. Electron cryo-microscopy and image reconstruction of adeno-associated virus type 2 empty capsids. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:997–1002. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]