Abstract

We compare the performance of multiple respondent-driven sampling estimators under different sample recruitment conditions in hidden populations of female sex workers in the midst of China’s ongoing epidemic of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). We first examine empirically calibrated simulations grounded in survey data to evaluate the relative performance of each estimator under ideal sampling conditions consistent with respondent-driven sampling assumptions and under conditions that mimic observed respondent-driven sampling recruitment processes. One estimator, which incorporates respondents’ reports on their network of contacts, substantially out-performs the others under all conditions. We then apply the estimators to empirical samples of female sex workers collected in two Chinese cities which include unique data on respondents’ networks. These empirical results are consistent with the simulation results, suggesting that traditional respondent-driven sampling estimators overestimate the proportion of female sex workers working in low tiers of sex work and are likely to overstate the STI risk profiles of these populations.

Introduction

Hidden and hard-to-reach populations, such as female sex workers and others at high risk of acquiring sexually transmitted infections (STIs), lack a sampling frame but are of special interest to public health.1 Traditional observation schemes for these populations—from direct observation to clinic-based inquiries to snowball sampling—are non-representative, impeding efforts to understand STI prevalence and transmission. Respondent-driven sampling has become the dominant method for collecting generalizable samples of hidden populations, with more than $150 million in federal funding.2–4 Respondent-driven sampling uses peer referral and a dual incentive structure to recruit a sample, compensating respondents for participating and referring others. Several estimators have been suggested to reduce sampling biases in respondent-driven sampling, but each makes stringent assumptions about recruitment dynamics that may diverge from the real world.5,6 Therefore, applied researchers have little guidance on which estimator to present in manuscripts and reports.

Here, we consider the relative performance of seven estimators under ideal sample recruitment conditions as well as real-world conditions observed in respondent-driven sampling studies of female sex workers in China, a hidden population with socially ordered tiers of sex work,7,8 each related to different levels of STI infection in the backdrop of a growing Chinese STI epidemic.9–11 We examine the following respondent-driven sampling estimators: 1) Naïve, 2) RDS1-SH12, 3) RDS1-DS13, 4) RDS1-DG14, 5) RDS2-VH15, 6) RDS2-SS16, and 7) RDS1-LEN17 (these estimators are discussed in the eAppendix). We anchor our evaluation in empirically grounded simulations,18 which combine novel statistical techniques for network estimation and prediction19,20 with data collected with respondent-driven sampling and a venue-based sampling approach among Chinese female sex workers. We follow up these analyses with an application of each estimator to two empirical samples of female sex workers in China.7,18

Prior Evaluations of respondent-driven sampling

Prior empirical assessments of the methodological validity of respondent-driven sampling have compared it to alternative sampling approaches,21–25 or benchmarked its estimates against known population parameters in non-hidden populations.26–29 Prior studies show that respondent-driven sampling recruits samples more quickly, more cost-effectively, and with more confidentiality than other approaches, but that its estimates “are reasonable but not precise” compared to benchmarks.27 Few comparative studies have examined the validity of respondent-driven sampling assumptions in the field, but recent work has shown that respondents in the real world recruit peers preferentially, violating crucial respondent-driven sampling assumptions.7,30 Other evaluations have simulated respondent-driven sampling-style samples on synthetic or empirical social networks and evaluated robustness to violations of assumptions about social network structure,4,5,31–33 data collection practices,5,16 and recruitment dynamics,6,18 but these studies typically only look at one or two estimators; more extensive comparisons have presented inconclusive findings.6

Methods

We focus on a variable of particular relevance to the expanding STI epidemic in China: the proportion of female sex workers in low tiers of sex work, who solicit clients in saunas, massage parlors, or streets, as opposed to high-tier female sex workers who solicit clients in karaoke bars, star hotels, and night clubs.7 Tiers are a distinctive feature of sex work in Asia34 and STI infections and risky behaviors are concentrated among female sex workers in low tiers.11,35,36 The tier-based social stratification of sex work has also been shown to bias recruitment dynamics in respondent-driven sampling, leading to overestimates of the proportion in low tiers.7,18

We first consider how respondent-driven sampling estimators perform under realistic and idealized recruitment conditions using multiple data sources including (a) a population social network generated from data collected in the PLACE-RDS Comparison Study of female sex workers in Liuzhou, China18,21, and (b) two sets of respondent-driven sampling chains simulated over this network, one that mimics recruitment patterns observed in the PLACE-RDS Comparison Study (“real-world scenario”), the other consistent with respondent-driven sampling assumptions (“ideal-world scenario”). These data sources are drawn from a previous study18 and are discussed in greater detail in the eAppendix. After examining simulation results, we also draw on empirical respondent-driven sampling data from the PLACE-RDS Comparison Study and the Shanghai Women’s Health Survey in an application section where we explore whether the simulation results generalize to empirical contexts. Respondents in both the PLACE-RDS Comparison Study and the Shanghai Women’s Health Survey provided verbal informed consent prior to participation. Surveys were administered face-to-face by trained interviewers in Mandarin Chinese or Zhuang. The PLACE-RDS Comparison Study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the National Center for STD Control, China and the Institutional Review Boards at the University of North Carolina and Duke University. The Shanghai Women’s Health Survey protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Wisconsin, Madison and of the Shanghai Institute of Planned Parenthood Research.

We examine both bias (accuracy) and efficiency (precision). Bias is measured as the mean difference between the statistic and parameter across simulated samples; it reflects tendencies toward over- or underestimation of population proportions of female sex workers in low tiers. To measure efficiency, we follow the respondent-driven sampling literature and examine design effects,37,38 which are the ratio of the variance of the sampling distribution of RDS estimates to the sampling variance that would be obtained via simple random sampling. Because a biased estimator with low design effects may be preferable to one which is accurate but inefficient, we also compute the root mean square error, defined as the square root of the sum of sampling variance and squared bias.

Results

Performance of Respondent-Driven Sampling Estimators in Simulated Samples

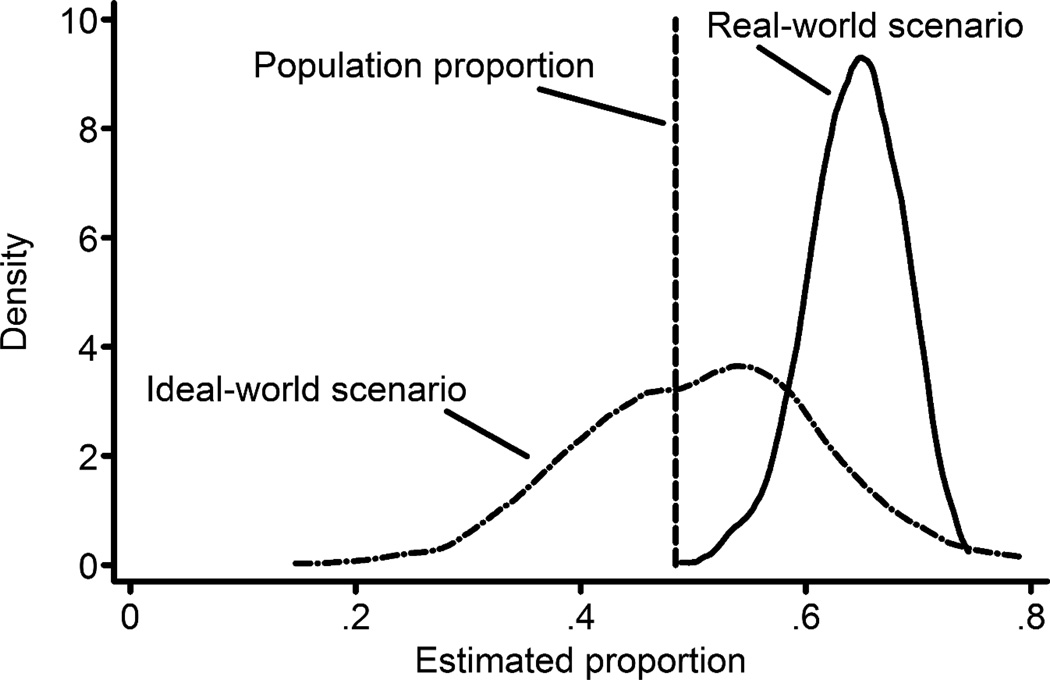

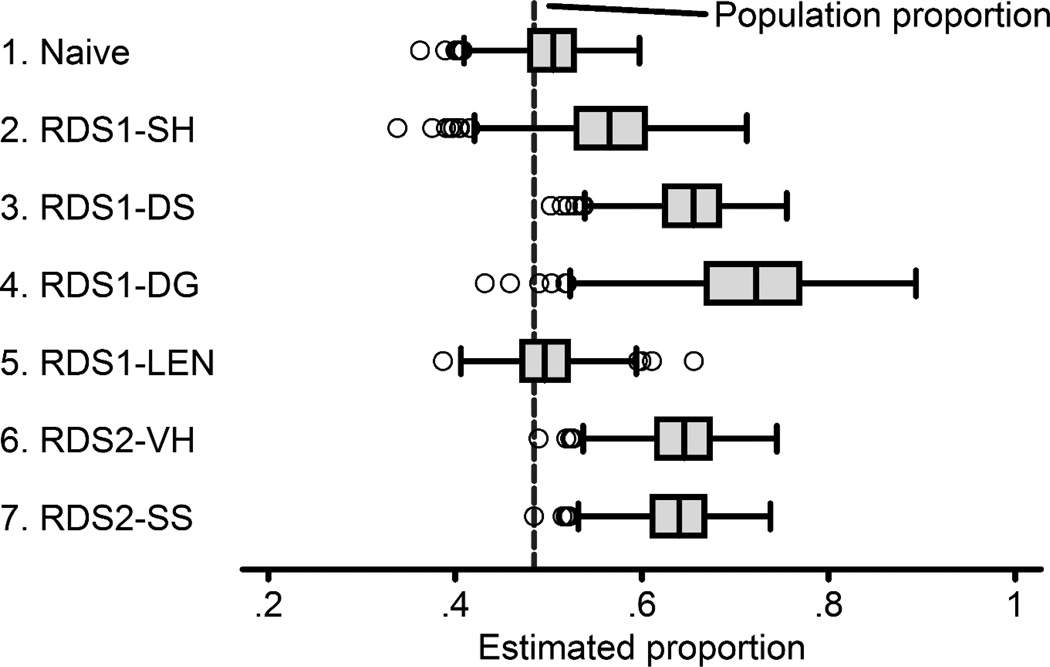

Figure 1 focuses on how an estimator which is commonly presented in the literature, RDS2-VH, performs under real-world vs. ideal-world conditions.5,18 Deviations from theoretical ideals in the real-world scenario lead to upward bias in the RDS2-VH estimator and to an overstatement of the fraction of the population in low tiers of sex work. However, estimates from the real-world scenario are less variable than estimates in the ideal-world scenario. Figure 2 shows the performance of all seven respondent-driven sampling estimators under the real-world scenario, where each tends to overstate the fraction of the population in low tiers of sex work. The RDS1-LEN estimator is least sensitive to these tendencies, followed by the Naïve mean, which has been reported to perform well in gold-standard evaluations.28

Figure 1. Distributions of estimates of proportion in low tiers of sex work using the RDS2-VH estimator, by seeding and recruitment scenario.

Notes: The population proportion is computed from the largest connected component of the simulated population network and is shown with a dashed vertical line. Population social network is priorities for local AIDS control efforts survey data source with venue size adjustments and weak geographic distribution of ties assumption (see eAppendix for description of population social networks). Distributions are plotted by kernel density estimation.

Figure 2. Distributions of estimates of proportion in low tiers of sex work in the real world recruitment scenario, by estimator.

Notes: Dashed vertical line indicates the population proportion. Population social network is priorities for local AIDS control efforts survey data source with venue size adjustments and weak geographic distribution of ties assumption (see eAppendix for description of population social networks). Recruitment and seeding scenario is matched seeds and matched recruitments.

Table 1 extends these evaluations to both recruitment scenarios and quantifies estimator performance in terms of bias, design effect, and root mean square error. The ideal-world scenario has smaller biases but larger design effects than the real-world scenario. The RDS1-LEN estimator is the least biased and has the lowest design effects under both scenarios. Other estimators show substantial biases or else persistently high design effects, at levels consistent with prior literature4,33,38, resulting in poor root mean square errors. These conclusions are robust to the underlying population distribution of female sex workers (see eAppendix).

Table 1.

Summary measures of estimator performance for proportion in lower tiers, by scenario.

| Bias | Design effects | Root mean square errors | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Real world scenario | |||

| 1. Naive | 0.018 | 2.969 | 0.040 |

| 2. RDS1-SH | 0.080 | 7.583 | 0.098 |

| 3. RDS1-DS | 0.168 | 4.303 | 0.173 |

| 4. RDS1-DG | 0.232 | 12.406 | 0.243 |

| 5. RDS1-LEN | 0.013 | 3.251 | 0.040 |

| 6. RDS2-VH | 0.159 | 3.990 | 0.164 |

| 7. RDS2-SS | 0.153 | 3.913 | 0.159 |

| Ideal world scenario | |||

| 1. Naive | −0.092 | 20.170 | 0.131 |

| 2. RDS1-SH | 0.006 | 13.046 | 0.075 |

| 3. RDS1-DS | 0.024 | 29.728 | 0.115 |

| 4. RDS1-DG | 0.028 | 74.102 | 0.180 |

| 5. RDS1-LEN | −0.018 | 6.267 | 0.055 |

| 6. RDS2-VH | 0.023 | 25.849 | 0.108 |

| 7. RDS2-SS | 0.018 | 25.557 | 0.106 |

Notes: Population social network data is drawn from PLACE data source with venue size adjustments and weak geographic distribution of ties assumption (see eAppendix materials for description of population social networks).

Performance of Respondent-Driven Sampling Estimators in Empirical Samples

Table 2 considers estimator performance in two empirical respondent-driven sampling samples of female sex workers in China, one recruited in Liuzhou for the PLACE-RDS Comparison Study in 2010,18 the other recruited in 2007 for the Shanghai Women’s HealthSurvey.7 Both studies gathered unique self-reports of network composition in follow-up interviews administered to recruiting participants when they collected incentives for successful referrals, which we use to provide the first empirical comparison of RDS1-LEN estimates to other RDS estimators.

Table 2.

Estimated proportions in low tiers of sex work in two data sets, by estimator.

| Liuzhou data | Shanghai data | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole samplea | Ego network subsetb |

Whole samplea | Ego network subsetb |

|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Summary statisticsc | ||||

| No. of observations | 583 | 310 | 522 | 271 |

| Proportion fully assigned | 0.803 | 0.465 | ||

| Earlier estimatorsd | ||||

| Naïve | 0.576 | 0.584 | 0.668 | 0.708 |

| RDS1-SH | 0.693 | 0.695 | 0.779 | 0.818 |

| RDS1-DS | 0.689 | 0.695 | 0.796 | 0.782 |

| RDS1-DG | 0.660 | 0.684 | 0.784 | 0.700 |

| RDS2-VH | 0.689 | 0.695 | 0.781 | 0.816 |

| RDS2-SS | 0.685 | 0.693 | 0.781 | 0.816 |

| Linked ego networks estimator (RDS1-LEN)e | ||||

| Accepted coupons | 0.658 | 0.752 | ||

| Offered coupons | 0.626 | 0.751 | ||

| Whole network | 0.634 | 0.815 | ||

Notes:

: these columns show the traditional respondent-driven sampling estimators computed on the entire empirical sample; because only respondents who completed follow-up interviews reported on their ego networks, the RDS1-LEN cannot be computed for 273 of the Liuzhou and 251 of the Shanghai cases.

: these columns show the traditional estimators and the RDS1-LEN by type of network reported on the subset of respondents who completed follow-up interviews (see eAppendix).

: rows in this section show summary statistics of interest; “Proportion fully assigned” indicates the proportion of cases in that sample’s follow-up questionnaire reports where we were able to assign 100% of self-reported uninvited network peers to a tier of sex work.

: rows in this section show estimates based on estimators in the literature prior to 2012; for the RDS2-SS estimator, the assumed population sizes of sex workers in Liuzhou and Shanghai were 7,500 and 15,000, respectively.

: rows in this section show estimates obtained using different network types reported on in the follow-up questionnaire and described in the supplemental appendix with the RDS1-LEN estimator.

The top portion of Table 2 shows few large differences between estimates obtained in the full sample vs. the subset of respondents who were administered network composition questions. The bottom portion of the table presents RDS1-LEN results for three measured network types: (a) invited peers who accepted the invitation, (b) all invited peers, and (c) a respondent’s whole network comprising both invited and uninvited peers. The eAppendix provides details on the measurement of these network types. Table 2 yields the following conclusions: the RDS1-LEN estimator generates estimates that suggest a smaller fraction of female sex workers in low tiers than earlier estimators, albeit with a few discrepancies across network types discussed in the eAppendix. These results are consistent with the simulation results, indicating a smaller proportion of female sex workers in low tiers than that estimated by other estimators when applied to real-world data.

Discussion and Conclusions

We extended prior evaluations of respondent-driven sampling by comparing seven estimators under realistic sample recruitment scenarios that applied researchers are likely to experience in the field. We find that Lu’s linked ego networks (RDS1-LEN) estimator outperforms all others in simulated samples under both ideal and realistic sample recruitment scenarios, and that these results generalize to two empirical samples of female sex workers. Compared with earlier estimators, the RDS1-LEN estimator generates lower estimates of the proportion of female sex workers in low tiers in empirical settings where respondent-driven sampling recruitment assumptions are known to be violated.7,18 By relying on self-reported personal network information, the RDS1-LEN estimator circumvents preferential recruitment biases, which confound other estimators.

This paper makes two contributions to the literature. First, we demonstrate that the RDS1-LEN estimator overcomes the two the most persistent problems plaguing other respondent-driven sampling estimators: bias in the face of realistic preferential recruitment and high design effects. We also demonstrate that it is possible to collect the type of data required by the RDS1-LEN estimator in empirical settings, and we consider three separate approaches to that data collection. We used a strong approach to derive these conclusions, relying on both simulated and empirical data about hidden populations of female sex workers and simulated and comparative approaches to data analysis, which enhances our confidence that the results can generalize, at least to other populations of female sex workers.

An important early paper on respondent-driven sampling estimators considered whether “to ask respondents what percentage of their friends fall into certain groups,”12 but the authors dismissed this approach because respondents may misreport peers’ epidemiologically salient attributes, especially difficult-to-observe characteristics or behaviors such as STI/HIV status or condom use. The chief limitation of our paper is that the RDS1-LEN estimator cannot readily be extended to estimate such unobservable characteristics, which are of considerable interest to public health practitioners. However, RDS1-LEN’s outperformance of earlier estimators suggests that further attention to its development is warranted, especially gaining accurate self-reports about respondents’ personal network composition. We have highlighted measures of three different personal network types in this paper, showing that they produce consistent estimates, but more work is needed to develop protocols for accurate personal network data collection in respondent-driven sampling.7,18 By comparing multiple respondent-driven sampling estimators, this paper will aid applied researchers in identifying which respondent-driven sampling estimator(s) should be presented in manuscripts and policy reports on the basis of their robustness to real-world sampling conditions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Statement about funding: The analyses described here are funded by NICHD grant 1 R01 HD068523 (Merli, PI) and grant 1 R01 HD075712 (Moody, PI). The collection of the data grounding the simulations and empirical analyses was funded through multiple sources. Funding for the collection of the PLACE-RDS Comparison Study data was provided by USAID under the terms of cooperative agreements GPO-A-00-03-00003-00 and GPO-A-00-09-00003-0; by NICHD through the UNC R24 “Partnership for Social Science Research on HIV/AIDS in China” (Henderson, PI; by UNICEF, UNDP, World Bank, and WHO through the “WHO Rapid Syphilis Test Project (WHO A70577)”; by the Duke University and University of North Carolina Center(s) for AIDS Research; and by the National Center for STD Control in China. The PLACE-RDS Comparison Study was led by Sharon Weir (PI), with co-investigators, Xiangsheng Chen and M. Giovanna Merli. The Shanghai Women’s Health Survey was funded by an NICHD/NIDA grant R21HD047521 (Merli, PI) and a Ford Foundation grant to the Shanghai Institute of Planned Parenthood Research (Ersheng Gao PI). We thank physicians and the outreach workers in the study areas for their hard work, and the study participants for their cooperation. We are also grateful to the Carolina Population Center for training support (T32 HD007168) and for general support (R24 HD050924). We thank participants at the Duke Network Analysis Center’s seminar series, and participants at the Sunbelt Social Networks Conference, especially Krista Gile and Mark Handcock, for helpful comments on an early version of this paper.

Footnotes

Statement about conflict of interest: The authors report no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Heckathorn DD. Respondent-Driven Sampling: A New Approach to the Study of Hidden Populations. Soc Probl. 1997;44(2):174–199. [Google Scholar]

- 2.White RG, Lansky A, Goel S, et al. Respondent driven sampling—where we are and where should we be going? Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88(6):397–399. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2012-050703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malekinejad M, Johnston LG, Kendall C, Kerr LRFS, Rifkin MR, Rutherford GW. Using Respondent-Driven Sampling Methodology for HIV Biological and Behavioral Surveillance in International Settings: A Systematic Review. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(1):105–130. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9421-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verdery AM, Mouw T, Bauldry S, Mucha PJ. Network Structure and Biased Variance Estimation in Respondent Driven Sampling. [Accessed September 25, 2013];2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145296. http://arxiv.org/abs/1309.5109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gile KJ, Handcock MS. Respondent-Driven Sampling: An Assessment of Current Methodology. Sociol Methodol. 2010;40(1):285–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9531.2010.01223.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tomas A, Gile KJ. The effect of differential recruitment, non-response and non-recruitment on estimators for respondent-driven sampling. Electron J Stat. 2011;5:899–934. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamanis TJ, Merli MG, Neely WW, et al. An Empirical Analysis of the Impact of Recruitment Patterns on RDS Estimates among a Socially Ordered Population of Female Sex Workers in China. Sociol Methods Res. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0049124113494576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang Y, Henderson GE, Pan S, Cohen MS. HIV/AIDS risk among brothel-based female sex workers in China: assessing the terms, content, and knowledge of sex work. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31(11):695–700. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000143107.06988.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen X-S, Peeling RW, Yin Y-P, Mabey DC. The epidemic of sexually transmitted infections in China: implications for control and future perspectives. BMC Med. 2011;9(1):111. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tucker JD, Cohen MS. China’s syphilis epidemic: epidemiology, proximate determinants of spread, and control responses. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24(1):50. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32834204bf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen X-S, Wang Q-Q, Yin Y-P, et al. Prevalence of syphilis infection in different tiers of female sex workers in China: implications for surveillance and interventions. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12(1):84. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salganik MJ, Heckathorn DD. Sampling and Estimation in Hidden Populations Using Respondent-Driven Sampling. Sociol Methodol. 2004;34(1):193–240. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heckathorn DD. Respondent-Driven Sampling II: Deriving Valid Population Estimates from Chain-Referral Samples of Hidden Populations. Soc Probl. 2002;49(1):11–34. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heckathorn DD. Extensions of Respondent-Driven Sampling: Analyzing Continuous Variables and Controlling for Differential Recruitment. Sociol Methodol. 2007;37(1):151–207. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Volz E, Heckathorn DD. Probability based estimation theory for respondent driven sampling. J Off Stat. 2008;24(1):79. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gile KJ. Improved Inference for Respondent-Driven Sampling Data With Application to HIV Prevalence Estimation. J Am Stat Assoc. 2011;106(493):135–146. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu X. Linked Ego Networks: Improving estimate reliability and validity with respondent-driven sampling. Soc Netw. 2013;35(4):669–685. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merli MG, Moody J, Smith J, Li J, Weir S, Chen X. Challenges to Recruiting Population Representative Samples of Female Sex Workers in China Using Respondent Driven Sampling. Soc Sci Med. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith JA. Macrostructure from Microstructure Generating Whole Systems from Ego Networks. Sociol Methodol. 2012;42(1):155–205. doi: 10.1177/0081175012455628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunter DR, Handcock MS, Butts CT, Goodreau SM, Morris M. ergm: A Package to Fit, Simulate and Diagnose Exponential-Family Models for Networks. J Stat Softw. 2008;24(3) doi: 10.18637/jss.v024.i03. nihpa54860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weir SS, Merli MG, Li J, et al. A comparison of respondent-driven and venue-based sampling of female sex workers in Liuzhou, China. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88(Suppl 2):i95–i101. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2012-050638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burt RD, Hagan H, Sabin K, Thiede H. Evaluating Respondent-Driven Sampling in a Major Metropolitan Area: Comparing Injection Drug Users in the 2005 Seattle Area National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System Survey with Participants in the RAVEN and Kiwi Studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20(2):159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kendall C, Kerr LRFS, Gondim RC, et al. An Empirical Comparison of Respondent-driven Sampling, Time Location Sampling, and Snowball Sampling for Behavioral Surveillance in Men Who Have Sex with Men, Fortaleza, Brazil. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(1):97–104. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9390-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Platt L, Wall M, Rhodes T, et al. Methods to Recruit Hard-to-Reach Groups: Comparing Two Chain Referral Sampling Methods of Recruiting Injecting Drug Users Across Nine Studies in Russia and Estonia. J Urban Health. 2006;83(1):39–53. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9101-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma X, Zhang Q, He X, et al. Trends in prevalence of HIV, syphilis, hepatitis C, hepatitis B, and sexual risk behavior among men who have sex with men. Results of 3 consecutive respondent-driven sampling surveys in Beijing, 2004 through 2006. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2007;45(5):581–587. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31811eadbc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wejnert C. An Empirical Test of Respondent-Driven Sampling: Point Estimates, Variance, Degree Measures, and Out-of-Equilibrium Data. Sociol Methodol. 2009;39(1):73–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9531.2009.01216.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wejnert C, Heckathorn DD. Web-Based Network Sampling Efficiency and Efficacy of Respondent-Driven Sampling for Online Research. Sociol Methods Res. 2008;37(1):105–134. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCreesh N, Frost SDW, Seeley J, et al. Evaluation of respondent-driven sampling. Epidemiol Camb Mass. 2012;23(1):138–147. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31823ac17c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCreesh N, Copas A, Seeley J, et al. Respondent Driven Sampling: Determinants of Recruitment and a Method to Improve Point Estimation. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e78402. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iguchi MY, Ober AJ, Berry SH, et al. Simultaneous Recruitment of Drug Users and Men Who Have Sex with Men in the United States and Russia Using Respondent-Driven Sampling: Sampling Methods and Implications. J Urban Health Bull N Y Acad Med. 2009;86(Suppl 1):5–31. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9365-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goel S, Salganik MJ. Respondent-driven sampling as Markov chain Monte Carlo. Stat Med. 2009;28(17):2202–2229. doi: 10.1002/sim.3613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu X, Bengtsson L, Britton T, et al. The sensitivity of respondent-driven sampling. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc. 2012;175(1):191–216. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mouw T, Verdery AM. Network Sampling with Memory A Proposal for More Efficient Sampling from Social Networks. Sociol Methodol. 2012;42(1):206–256. doi: 10.1177/0081175012461248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lim LL. The Sex Sector: The Economic and Social Bases of Prostitution in Southeast Asia. International Labour Organization; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Q, Yang P, Gong XD, et al. Syphilis prevalence and high risk behaviors among female sex workers in different settings. Chin J AIDS STDs. 2009;15:398–400. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang L, Ding ZW, Ding GW, et al. Data analysis of national HIV comprehensive surveillance sites among female sex workers from 2004 to 2008. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2009;43(11):1009–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salganik MJ. Variance Estimation, Design Effects, and Sample Size Calculations for Respondent-Driven Sampling. J Urban Health. 2006;83(1):98–112. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9106-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goel S, Salganik MJ. Assessing respondent-driven sampling. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107(15):6743–6747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000261107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.