Abstract

In order to make EBTs available to a large number of children and families, developers and expert therapists have used their experience and expertise to train community-based therapists in EBTs. Understanding current training practices of treatment experts may be one method for establishing best practices for training community-based therapists prior to comprehensive empirical examinations of training practices. A qualitative study was conducted using surveys and phone interviews to identify the specific procedures used by treatment experts to train and implement an evidence-based treatment in community settings. Twenty-three doctoral-level, clinical psychologists were identified to participate because of their expertise in conducting and training Parent-Child Interaction Therapy. Semi-structured qualitative interviews were completed by phone, later transcribed verbatim, and analyzed using thematic coding. The de-identified data were coded by two independent qualitative data researchers and then compared for consistency of interpretation. The themes that emerged following the final coding were used to construct a training protocol to be empirically tested. The goal of this paper is to not only understand the current state of training practices for training therapists in a particular EBT, Parent-Child Interaction Therapy, but to illustrate the use of expert opinion as the best available evidence in preparation for empirical evaluation.

Keywords: Evidence-based treatment, training practices, implementation science, qualitative research methods, expert opinion

1. Introduction

Evidence-based treatments (EBTs) are interventions which have an extensive research base for therapeutic change produced for specific clinical presentations (Kazdin, 2008). Several expert panels have recommended incorporating evidence-based treatments (EBTs) into standard clinical practice, calling it a priority for improving the quality of mental health services (President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2004). Panel recommendations to incorporate EBTs led to calls for the scaling up of EBTs and a demand for training therapists in community-based settings. However, reports continue to highlight a lack of access to EBTs in community settings (President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2004; U.S. Public Health Service, 2009). Research continues to indicate that same lack of access and poorer outcomes for community treated children compared to children treated at university clinics (Costello, Jian-ping He, Sampson, Kessler, & Merikangas, 2014; Rones & Hoagwood, 2000) and that “treatment as usual,” or usual clinical care, for children in community settings is considerably different from EBTs. (Garland et al., 2010).

The lack of both comprehensive guidelines to support the transfer of EBTs to community therapists (McHugh & Barlow, 2010) and empirical information regarding effective knowledge and skill transfer (Fixsen, Naoom, Blase, Friedman, & Wallace, 2005; Gotham, 2004) creates numerous challenges in the implementation of EBTs in community settings. The differences in the characteristics of community therapists and those involved in controlled research studies examining EBTs leave a particular paucity of data about how to most effectively train those who provide care in community settings (Herschell, Kolko, Baumann, & Davis, 2010). A majority of community-based clinicians are masters-level therapists, with an “eclectic” theoretical orientation, who value the quality of the therapeutic alliance over the use of specific techniques (Garland, Kruse, & Aarons, 2003). To date, the most common way to train community therapists in EBTs has been to ask them to read written materials (e.g., treatment manuals) or attend standalone workshops (i.e., one to two-day workshops without additional training follow up), but there is little to no evidence that this ‘train and hope’ approach (Henggeler, Schoenwald, Liao, Letourneau, & Edwards, 2002), similar to continuing education formats, will result in positive, sustained increases in skill and competence (Beidas & Kendall, 2010; Herschell et al., 2010).

Trainers of EBTs have met the demand for community trained therapists by developing training strategies based on their years of clinical experience and expertise (e.g., Landes & Linehan, 2012). Training protocols have been developed for several EBTs, which have contributed to their successful implementation (Herschell, McNeil, & McNeil, 2004). Examples include Multisystemic Therapy (MST Services, Inc., 2014), Dialectical Behavior Therapy (Linehan, 1993), and Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care (TFC Consultants, Inc., 2014). Similar to PCIT training, these training processes are often extensive and include multiple training days with time in between for therapists to practice skills with consumers and receive feedback from experts through coaching or consultation (Beidas & Kendall, 2010; Herschell et al., 2010; Sholomskas, Syracuse-Siewert, Rounsaville, Ball, & Nuro, 2005). Several training models are prominently used to implement EBTs to community settings (e.g., cascading model and learning collaborative model). These models vary in how materials are delivered and emphasized across the training process. For example, a cascading model places greatest training emphasis on the role of the trained therapist in delivering the clinical model (e.g., Chamberlain, Price, Reid, & Landsverk, 2008), while a learning collaborative model includes involvement of multiple levels within the organization (e.g., administrator, clinical supervisor, therapist) and specific components which address the organizational context (e.g., culture, climate, resources, leadership engagement) in which the intervention will be implemented (Damschroder et al., 2009).

1.1 Use of Expert-Informed Strategies

Expert opinion can be systematically organized to provide the best available evidence about a topic which has limited empirical study. In the medical and mental health fields, criterion sampling can be used to select and integrate expertise of individuals with a particular knowledge base. Expert opinion has been used to improve the reporting of clinical trials (e.g., Tetzlaff, Moher, & Chan, 2012), provision of systematic reviews of controlled trials (e.g., the Cochrane Collaboration), and development of practice guidelines (e.g., August et al., 2008; Frances, Kahn, Carpenter, Frances, & Docherty, 1998; Waltz et al., 2014). These methods embody practice-based evidence through synthesizing existing expertise in order to develop procedures to be empirically tested. Subsequently, these methods provide results that are relevant, readily implementable, and integrate clinical experience with the best available systematic research (e.g., Hanson et al., 2013), which overcome some of the limitations identified with EBT (Minas & Jorm, 2010; Straus & Sackett, 1998; Strauss, 1987). Due to the existing gaps in knowledge related to training methods of EBTs in community settings, qualitative research methods are indicated (Creswell, 2013). The goal of grounded theory study is to generate or discover a “unified theoretical explanation” for a process or action (Corbin & Strauss, 2008, p. 107), which explains practice and provides a framework for further research. A particular EBT, PCIT, was selected to serve as an example for several reasons: 1) children with disruptive behavior difficulties represent the largest source of referrals to mental health agencies, accounting for one third to one half of child outpatient mental health referrals (Kazdin, 1995), 2) a majority of these referrals are received in early childhood (e.g., Garland et al., 2010), 3) PCIT is an early childhood EBT which if effectively provided can change the child’s developmental trajectory, and 4) it is an EBT with developed training requirements, a highly structured treatment protocol which eases the development of specific training practices, and has been recommended for wide-scale implementation.

1.2 Examining Training Practices of one EBT as an Example: Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT)

PCIT is a well-established, evidence-based treatment for young children (aged 2.5 – 7) who are experiencing externalizing behavior problems such as aggression, noncompliance, and defiance (Eyberg et al., 2001). PCIT was developed from Hanf’s two-stage model (Reitman & McMahon, 2013) which includes a relationship focused, behaviorally-oriented play therapy stage (child directed interaction [CDI]) and a behavior management focused stage (parent directed interaction [PDI]). Accordingly, PCIT consists of several core features: (a) the parent and child are actively involved together in treatment sessions, (b) interactions are coded to determine progress and treatment planning, (c) traditional play-therapy skills are taught to enhance the quality of the parent-child relationship, (d) problem-solving and behavior management skills are taught to develop family success in addressing problem behaviors, which include the use of a specialized timeout procedure, (e) parents are coached with the goal of reaching a level of mastery of both play-therapy and behavior management skills, (f) the treatment model is clinically validated, and (g) changes are made based on empirical evidence (Eyberg, 2005). PCIT has also been established as a “Best Practice” for children with histories of child physical abuse (e.g., Kauffman Foundation, 2004). For a more detailed description of PCIT see Scudder, Herschell and McNeil (2015). Expert groups have recommended the widespread implementation of PCIT (e.g., Substance Abuse Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA), National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN)), but the best strategy for how to scale-up the treatment for broad public health impact remains in question.

1.2.1 PCIT training history

Since PCIT’s development, PCIT training has been primarily provided in training clinics housed in university-based, doctoral-level psychology departments and university-affiliated medical centers. Training in PCIT, like many other EBTs, was historically conducted using an apprenticeship model with intensive supervision of PCIT-related research and clinical skills under the direction of an expert, faculty-level PCIT scientist-practitioner. As the demand for PCIT has increased, it has been implemented more broadly and other modalities of training and supervision have been tried. States such as California, Delaware, Iowa, and Pennsylvania have had large-scale dissemination efforts sponsored by a variety of funding sources (e.g., public and private foundations, SAMHSA, NIMH). PCIT International was developed as a business with the primary mission to ensure high fidelity as well as “foster the growth and expertise of the network of local, regional, national, and international PCIT therapists” (www.pcit.org).

PCIT International has published training guidelines and requirements for certification (PCIT International, 2009; 2013) that outline requirements of training at all levels (i.e., PCIT therapists, Level I Trainers, Level II Trainers, and Master Trainers). The PCIT International Certified PCIT Therapist Training Requirements (PCIT International, 2013) specifically outline therapist competencies to be assessed across the training process. At least 40 hours of in-person training or 30 hours of in-person training supplemented with 10 hours of online training is required and should include: (a) an overview of PCIT’s theoretical basis, assessment and behavioral coding practice, 2011 PCIT treatment protocol, and session structure, (b) clinical case review of relatively straight-forward to very complex cases, and (c) interactive discussions, modeling, role-plays, and live demonstrations with children and families. These requirements are largely based on clinical experience, but there have also been some empirical investigations examining specific components of PCIT training.

1.3 Empirical Examinations of PCIT Training Components

Training manuals, workshops, and seminars alone have been shown to be insufficient to achieve reliable and competent PCIT skill transfer from training to service provision (Herschell et al., 2009). Studies evaluating the utility of self-directed trainings and workshops have documented that these methods alone do not routinely produce positive outcomes (Beidas & Kendall, 2010; Herschell et al., 2010). The PCIT International Training Guidelines acknowledge that these training methods are insufficient. Instead, they require that following an initial in-person training, trainees complete clinical case consultation with a PCIT trainer until they have graduated at least two families from PCIT and to continue consultation until all required training competencies are met. Workshop follow-ups are used to help sustain training outcomes.

Several authors have started examining the incorporation of technology to specific components of training such as using telemedicine technology for consultation (Funderburk, Chaffin, Bard, Shanley, Bard, & Berliner, 2014; Funderburk, Ware, Altshuler, & Chaffin, 2008; Wilsie & Brestan-Knight, 2012). Telemedicine technology, such as Remote Real-Time Coaching, allows the PCIT trainer to actively coach the PCIT trainee during therapy sessions, which may be a more time efficient method to increase trainee clinical competencies when compared to standard consultation conference calls. PCIT trainees (n = 10) rated the real-time feedback and observation higher than consultation calls for skills-based elements of consultation and rated consultation calls higher than Remote Real-Time for conceptual elements (Funderburk et al., 2008). When given the choice of only one form, all participating trainees chose Remote Real-Time as the preferred form of consultation. When tested in a larger trial conducted across two states and involving 80 therapists and 330 cases, live video consultation (remote real-time) was found to help improve client outcome by one standard deviation in comparison to standard consultation, which had no association with client improvement (Funderburk et al., 2014).

1.4 Empirical Examinations of PCIT Trainee Characteristics

Therapist characteristics and attitudes towards the adoption of EBTs have been shown to impact dissemination and implementation efforts (Herschell, McNeil, & McNeil, 2004). Therapist verbal behavior and communication styles (e.g., use of labeled praise) early in treatment have been shown to be related to family success in skill development and treatment completion (Harwood & Eyberg, 2004; Herschell, Capage, Bahl, & McNeil, 2008). In training, initial therapist attitudes have been shown to be related to their participation and satisfaction with varying levels of post-workshop training support and case enrollment for PCIT (Nelson, Shanley, Funderbunk, & Bard, 2012).

Studies examining components of PCIT training and characteristics of trained clinicians assist in understanding effective training practices; however, are unable to fully examine how individual trainers and groups incorporate these components into larger training protocols. Similar to the training of other EBTs, there is a gap between the PCIT International Training Guidelines and the empirical literature, which may be bridged by the experience of expert scientist-practitioners. Just as years ago treatment developers sought to uncover the “black box” of therapy (e.g., Bearman et al., 2013; Hoagwood, Atkins, & Ialongo, 2013), the goal of the current study was to uncover the contents of the “black box” of training in an EBT. The central aim of the current study was to operationalize the training protocols of PCIT trainers of community-based therapists.

1.5 Protocol Development

In recent decades, comprehensive clinical protocols have allowed EBTs to be easily identified and empirically evaluated (Chambless et al., 1996). However, a protocol for training community-based therapists has not yet been developed or empirically studied (Herschell et al., 2010) and the current practices of clinical trainers have not yet been well documented. This is particularly relevant as community-based clinical training is a complex, expensive, multifaceted intervention, which requires skilled decision-making.

The development of a clinical training protocol based on current training practices is considered an initial and necessary step towards developing evidence-based training models (Tetzlaff, Chan, et al., 2012; Tetzlaff, Moher, et al., 2012). In the current study, we chose to report similarities and differences in expert opinion. The themes that emerged following the final coding were used to construct a theory of current training practices and a training protocol that is now being empirically tested (R01 MH095750; A statewide trial to compare three training models for implementing an EBT).

2. Method

A grounded theory approach (Creswell, 2013; Strauss & Corbin, 1998) was used to acquire an in-depth understanding of the current PCIT training practices. In turn, a framework of the training process was developed in order to operationalize a detailed training protocol informed by expert delivery of PCIT training. This training protocol is now being tested in a large training and implementation trial (R01 MH095750).

2.1 Trainer Participants

Trainers were invited to participate if they had been identified as a “Master Trainer” (Parent-Child Interaction Therapy, 2011) or if they had led a large-scale PCIT initiative to train community-based clinicians. The practices of these trainers were of specific interest because the considerations and practices used to train multiple agencies at once differ from training practices used to train clinicians within one agency. Twenty-three trainers were invited to participate. Eighteen trainers (78.3%) participated in interviews guided by the semi-structured format; sixteen trainers (69.6%) also completed an online current training practices survey.

Trainer participants were asked to provide their expert opinion based on their current training practices. Particular steps were taken to keep trainers’ individual responses confidential. In several instances, the reported training practices varied from the recommended training guidelines, which are based on collective experience and recommendations. Across the interviews, trainer participants frequently commented that they strived to implement practices at or above the recommendations, however training practices have evolved over time and formal training guidelines did not exist until 2009 (i.e., PCIT International, 2009).

2.2 Training Interview and Survey

A semi-structured interview outline was developed based on the PCIT International Training Guidelines (PCIT International, 2009). Additional items were constructed with the goal of operationalizing all components of the current training practices (See Table 1 for interview). Each interview, conducted by a PhD-level clinical psychologist (ATS), lasted from 45 to 120 minutes, and was audio recorded. A bachelor’s level research associate transcribed the interviews verbatim. Collectively, 427 pages (i.e., a range of 13–53 pages per participant) were cleaned and checked for accuracy.

Table 1.

PCIT Trainer Interview

| Pretraining Preparation/ Support & Startup |

|

| Training |

|

| Organization of Training Records |

|

| Consultation |

|

| Case Review |

|

| Follow up Support (after consultation period) |

|

| Use of training supports |

|

| Trainer Reflections on Training |

|

3. Results

3.1 Data Analysis

The research team contracted with an independent data unit at the university which specializes in qualitative data analysis to assist in code construction, operationalization, and coding the written interview transcripts. Data analysis was guided by basic principles of grounded theory research (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). The developed codebook contained 52 descriptive codes based on relevant PCIT training topics (e.g., pre-training preparation, workshop training, consultation, and follow up support). Two coders independently coded all transcripts for major domains of inquiry using qualitative data analysis software (ATLAS.ti, 2006). Both coders had at least three years of coding experience and had previously worked on multiple qualitative coding projects through the data unit. Coder 1 was a Caucasian male with a bachelors’ degree in History and English. Coder 2 was a Caucasian female with a PhD in Geography. Initial kappa calculations ranged from .29 to .87 across codes. Kappas for primary codes were high (Pre-training Preparation=0.71, Training Workshop= K=. 77, Consultation K=.87, Follow Up Support K=.85). Following initial kappa calculations, the coders identified and discussed any disagreements that occurred with independent coding. Consensus was reached in most cases. In cases in which the coders did not reach consensus, the text was discussed with a project manager and a member of the research team to clarify and achieve a consensus about the statement. The project manager had doctoral training in clinical psychology and six years of experience overseeing qualitative data projects through the data unit. First, the transcripts were open coded for major categories of a core training process. From this coding, categories were developed around the core process. A visual model was created which allowed for propositions to be made about the relations among categories within the model and a theory of current training practices to be developed. The initial categories were finalized after a comparative process in which each statement was checked against similar data (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Subsequently, the coding team discussed the content of each category, reviewed interrater reliability by code, and refined the coding scheme by expanding, collapsing, or eliminating codes until there was consensus. Throughout the coding process the coding team was in regular contact with the primary researchers to discuss coding progress as well as nuances of the EBT and training practices to ensure accurate coding.

3.2 General Themes

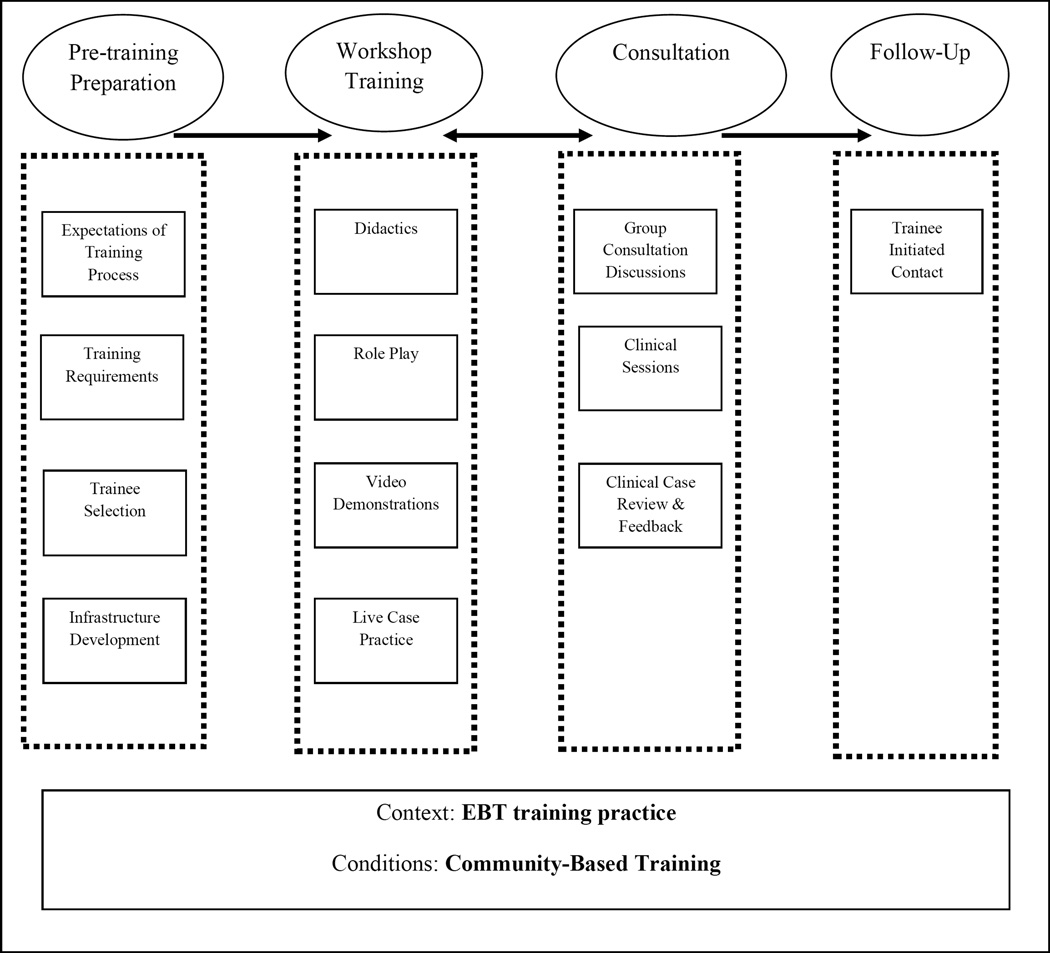

In this section general themes are reported and presented based on the order of progression of most trainings. The training period was generally discussed as consisting of several components: pre-training preparation, workshop trainings, consultation, and follow up (see Figure 1). Collectively, training across the training period was identified as a mechanism to facilitate trainee ‘s continual movement towards independence with the training model. Trainers frequently conceptualized training as a parallel process to the PCIT therapy process. For example, in PCIT, therapists coach using “scaffolding” or “shaping” of parent skill. One trainer described this process by saying that therapists should use “behavioral principles to shape a parent’s skill acquisition--their coaching changes from one session to another-- and from one moment to another.” Most trainers discussed the importance of progressing with training components based on trainee skill level. They also discussed how specific treatment techniques should change over time, beginning with less demanding interactions and moving to more demanding interactions. For example, training components were presented first using less demanding methods such as modeling of skills by the trainer and then moved towards role-plays and case demonstrations by trainees. They discussed increasing trainee buy-in and comfort through the training process by informal group activities such as “providing food,” “eating meals together,” or having activities towards the end of training to “process the experience as a training group.” Trainers reported many common elements across the training process. For example, all trainers include PowerPoint presentations and most integrate a combination of role-plays, live demonstrations, and video presentations. Additionally, some training components appear more variable across trainings such as the level of emphasis placed on training particular details of PCIT (e.g., backups to the timeout chair), methods used to review therapists’ cases, elements added to address clinical topics or populations uniquely relevant for particular training groups (e.g., child maltreatment, military families), and the timing and method of evaluation of trainee competencies.

Figure 1.

Components and Subcomponents of Training Practices

3.3 Areas of Common Elements

3.3.1 Pre-training preparation

Most trainers emphasized an importance in pre-training preparation and a need for increased focus on training preparation. For example, one trainer noted, “Pre-training preparation and selection is key. Those are two things that have emerged in the implementation research as really important. And I think it’s especially important for PCIT because it’s a very intensive model… to give people a sense of what it looks like and how fast paced it is - when you say to somebody, ‘PCIT is a very structured EBT, is that comfortable for you?’ They say ‘yes,’ but they’re thinking of a less intensive model, I can guarantee it… I think it’s really really important.” Most trainers reported contact prior to training to include in-person or phone meetings. Many trainers reported requesting trainees to review materials such as articles and short video overviews presented by a PCIT expert. Some included other preparation such as the completion of a “pre-training application” or “trainee survey,” an “agency site visit,” or “review of the PCIT treatment manual,” the “DPICS manual and workbook,” or other created introductory materials. Some also reported having trainee agencies assist with the purchasing of “PCIT treatment manuals,” “PCIT books,” or “printing of training materials.” As depicted in Figure 1, trainers who incorporated pre-training meetings or site visits into their training preparation described these visits as assisting with agency startup which might include: 1) discussing expectations of the training process such as “the agency’s commitment to therapist time in co-therapy or peer consultation,” 2) understanding training requirements such “videotaping sessions” and case selection, 3) informing topics related to trainee selection such as “trainee characteristics” (e.g., masters level, license or license eligible), and 4) planning for infrastructure development such as ―establishing a referral process,” “identifying an observation room,” and “developing a timeout space.” Half of the trainers required trainees to identify 2 to 3 PCIT-eligible families prior to receiving training and an additional 25% reported ‘strongly recommending’ identification of PCIT-eligible families prior to training.

3.3.2 Workshop training components

Trainers reported general characteristics of their training workshops as well as specific details related to workshop structure. Face-to-face training time varied between 5 and 8 days and was most commonly reported as 7 days. Training workshops most commonly included 8 trainees, although workshops range from 2 to 12 trainees with 1 to 12 trainees per agency. A few trainers indicated the importance of the trainer to trainee ratio and suggested ratios of 1 to 4 or 1 to 6. A majority of trainers reported providing continuing education credits (56%), which they most commonly offered for psychologists (53%), social workers (29 %), and others such as licensed mental health counselors, marriage and family therapists, and professional counselors (18%).

Trainers reported training agencies which provide services in a variety of settings such as outpatient community-based clinics (94%), outpatient private practice (75%), outpatient university settings (63%), home-based (50%), school-based (38%), inpatient (25%), and other settings such as residential treatment centers and military-based service settings (13%). Trainees served the following professional roles: masters-level therapists (94%), clinical psychologists (81%), supervisors (75%), administrators (38%), medical professionals (31%), Child Advocacy Center therapists (25%), and others such as students, interns, and researchers (50%). Most trainers (75%) reported also training individuals serving as clinical supervisors of PCIT services. Most commonly, trainers reported conducting trainings in a university-based setting (81%) or at community mental health centers (44%). Of the trainers using both types of training sites, 30% indicated that trainees more commonly travel to the trainer’s site.

Generally, trainers reported that role-plays are often used to give the participants experience in demonstrating skills. A majority of role-plays emphasized the demonstration of parent mastery skills, coding, and coaching, and to a lesser degree other clinical competencies. Most but not all of the trainers incorporated clinical videos and live skill practice with families or children during their training. Many trainers noted the central difference in coaching during CDI versus PDI. In CDI, coaches work to keep parents in the lead as they shape the use of specific selective attention skills, while in PDI, coaches lead parents until they demonstrate the use of specific disciplinary skills.

3.4 Areas of Greater Variability

3.4.1 Workshop training process

The process and timing of the workshop training components was one area found to have greater variability among trainers. Specific details from the training schedules (e.g., number of breaks, length of training days) were collected and incorporated into the developed protocol but are beyond the scope of this paper. Trainers frequently agreed on the components needed in training but varied on how they chose to rollout particular training components such as coding and coaching. Trainers noted that considerations of trainee comfort and engagement with the training process were primary factors in their decision of the order to introduce specific components. In addition to the ordering of specific components, the amount of detail and mode of delivery also appeared to vary across trainings. For example, use of PowerPoint presentations across the course of training ranged from approximately “3 hours” to “20 hours.” Trainers also reported that their individual delivery of training may vary from one training to the next based on tailoring to trainee needs, knowledge, and skill level.

Trainers checked clinicians off of predetermined clinical competencies across the training and consultation periods; however, trainers varied in the methods and timing of these competency check offs. Some trainers relied more heavily on the in-person training period while others relied more heavily on clinical case review of therapists’ demonstration of the competencies with their clinical families. For example, trainer responses ranged from “most [competency check offs] are done in the first 40 hour training—and then a bunch of them are done in the two- day advanced training. And then the last three of them, I save to check off [during the consultation and case review period]” to “during the face-to-face training we do check offs for parent mastery skills but… it’s in their cases, that we’re really checking them off [of their other clinical competencies].” Several trainers also reported their incorporation of constructed measures such as a “coach’s quiz” to assess therapists’ CDI and PDI coaching knowledge and a “coach-coding system” to provide feedback on therapists’ coaching skills. Trainers also reported differences in the number of trainers and training supports attending trainings. While some trainers train independently, others co-train with graduate students or predoctoral interns, and still others report large training teams of up to nine members. Those reporting large training teams discussed the importance of trainers being coordinated and interchangeable.

3.4.2 Timeout training

Unique implementation challenges are found with all EBTs. A particular challenge of PCIT is the implementation of the highly structured timeout procedure (see Eyberg & Funderburk, 2011 for a full description). Subsequently, we asked trainers to discuss their training of timeout in great detail. All trainers were asked what timeout backups they: 1) were training, 2) the depth of this training, and 3) what methods trained agencies were using. All trainers reported that they trained the timeout backup room. Four trainers trained alternatives to the timeout chair only if needed, seven provided a brief discussion or demonstration of the swoop-and-go (i.e., parent takes the toys and stands outside the therapy room), and seven emphasized both the timeout room and swoop-and- go procedures, having trainees practice both procedures in role-play during the face-to-face training. Twelve trainers provided estimates of the practices in the agencies that they had trained. Five trainers reported that most agencies have timeout rooms built in their PCIT session room, and seven trainers reported that most agencies use backups such as “an adjacent therapy room” or “swoop- and- go procedure.” The use of alternative backup methods was reported to be commonly utilized for two reasons: 1) lack of resources such as funding and space and 2) a philosophical disagreement at the agency or system level with use of a timeout room.

3.4.3 Clinical case review

Following the workshop training, most trainers conducted clinical case review. However, trainers varied in the structure and method used. Many, but not all of the trainers, used video for clinical case review. Others used video streaming or live in-session review. Regardless of method, trainers often provided highly detailed feedback after reviewing clinical sessions. Some trainers noted the specific utility of clinical case review in revealing clinical challenges or low adherence to the PCIT model; which may not be reported in consultation calls or in self-reported metrics. There was also variability in how trainers decided that remediation was needed for case review. For example, one trainer indicated “If they hit the integrity checklist items, then that’s good enough. And I can give them some feedback to try to make them better.” While another trainer noted, “even though they completed those things [items on the integrity checklist]… I request another video if… its superficial detail or I don’t think they grasped it.” Additionally, trainers varied in their feedback methods as some trainers provided written feedback and then set up an individual phone call to discuss feedback further while others emailed feedback or discussed feedback on group consultation calls.

3.4.4 Consultation

Consultation was reported to be less structured than in-person training and more varied among trainers. The frequency of scheduled consultation ranged from weekly to monthly one-hour sessions. Consultations generally were done as group conference calls, although some were done live, with members of the same training group or from the same agency. Generally, trainers discussed using consultation discussions to highlight experiences commonly addressed during PCIT. For example, one trainer listed several common issues brought up during consultation calls such as “how to get the parents to do their homework, attend sessions every week, and use labeled praises.” The trainer further reflected that trainees often experience “similar issues so even though we’re talking about specific clients I always say, “Ok, here’s an issue that you are all dealing with-- so let’s talk about it in regards to a specific case.” Consultations usually first focused on particularly challenging cases, before focusing on any feedback the trainer wants to give from their case reviews or other topics. The content of consultation appeared to vary based on the frequency of contact. Typically, time was allotted to all of the participants at each consultation. Most trainers consulted with trainees for 1 year following initial training with a range from 6 months to 3 years. Most mentioned that the duration of the consultation period is determined by the graduation of 2 cases, regardless of how long that takes.

3.4.5 Follow-up support

Following the consultation period, the progression of training contact continued to a less structured, informal support. It was most often described as “as needed” and consisting of “email or phone contact.” Trainers reported the follow-up period to be supplemental and optional; not all trainees remained in contact with trainers during this period. Trainers indicated that often clinical discussion becomes more advanced and finessed as therapists attain basic foundations of the intervention. In addition to the most commonly cited methods, trainers also reported formats such as regional conferences and continued consultation calls. Trainers varied on their report of the importance or feasibility of follow-up support. Although most reported conducting follow-up support at no charge, some discussed formal contracts. The longest reported duration of “as needed” follow-up contact was eight years, which was reported by two independent trainers.

3.5 Trainer Reflections on Trainings

Strong opinions related to some training topics were relatively common across trainers and training groups, and were coded as opinions of training positives and opinions of training challenges.

3.5.1 Training positives

Trainers reflected positively about involving either a live demonstration family or children during the training workshop, noting that this allowed trainees to visualize the multiple components of PCIT sessions. Several trainers referenced their live case demonstrations as “one of the most highly favored aspects” of their trainings. Trainers also shared strong positive preferences for observing trainee cases live and providing live consultation. Trainers often recognized that live methods were preferred but not always feasible, also sharing strong positive remarks regarding the incorporation of different types of technology to make distance case review and consultation as active as possible. For example, one trainer reflected “I prefer to be there in person if I can. If I can’t be there in person, I prefer next to be there on the web. Videotape review I think is by far the weakest. I do it because I have some [therapists] that don’t have access to any of those systems… you see that they can do it on the tape but… it is easier to correct something right as it’s happening.” Lastly, trainers emphasized the importance of activities to build comfort during the training process such as meals or closing activities. For example, one trainer reflected, “I’m really convinced that you have to create a very positive attitude of safety for therapists because you are going to be giving corrective feedback-- and part of that is that they have to feel pretty safe. I do some things at the training to increase the feelings of safety, including we eat together…to help people feel comfortable. We are very low key, very informal in order to help people feel comfortable.”

3.5.2 Training challenges

Trainers also consistently noted areas of challenge such as pre-training preparation and infrastructure development, obtaining and calculating coding accuracy during training workshops, case review, and subjectivity of assessing some clinical competencies. Trainers commonly discussed issues involving having infrastructure and adequate facilities at community agencies for use of timeout rooms, use of equipment such as the bug-in-the-ear, call pods, video recording and transfer equipment, and observation rooms with one-way mirrors. A few trainers specifically noted agency administrators’ limited knowledge about the infrastructure requirements of PCIT. For example, one trainer said “It seems like the administration is always getting caught up with PCIT after the fact, when the therapists come back to their agency, they’re like, “Oh, this is what it is.” And they don’t know until the therapist goes back, they don’t really get what it is.”

Many trainers used the process of video submission for case review. Although this was valued, they indicated that submitting videos was often difficult for therapists to complete. One trainer reflected on therapists’ struggles to submit videotape saying, “One of the big problems I run into for community dissemination which is kind of simple, but it’s really not--is the taping.” The trainer reflected the reactions of some community-based therapists by saying “‘What do you mean we have to tape things? I’ve been doing this for 20 years; I’ve never taped a session.”‘ Additionally, trainers reported that providing detailed, written feedback was useful yet time intensive and less efficient than more active or in-the-moment methods.

Trainers also frequently discussed their challenges with the subjectivity involved in providing feedback following case review. For example, one trainer remarked “Honestly, I watch it and I think -’Can this person do this the rest of their career, in the exact same way, would that be ok?’ If I said ‘no’, then I try to articulate to them why… “ Trainers also provided examples to illustrate that reaching 80% treatment integrity may be adequate, but not always sufficient for demonstrating competent treatment delivery. Another noted concern was the ongoing challenge of having video examples of clinical cases consented and able to be shown during face-to-face trainings of PCIT. Lastly, trainers reported that successful completion and “graduation” of families through treatment often takes trainees a long time, suggesting that the nature of outpatient therapy allows many trainees to see numerous cases into the second stage of the treatment program without meeting official graduation criteria. Trainers reported that therapists have taken “six months” to “three years” to successfully graduate two cases.

4. Discussion

Although EBTs have well-established evidence bases, empirical examination of training practices for community-based therapists in the delivery of EBTs is limited. The bulk of literature related to training methods for EBTs has more narrowly focused on particular components of training (e.g., consultation, supervision, or behavioral rehearsal). Few EBTs have yet to have detailed protocols for training community-based clinicians (Herschell et al., 2010). This study illustrated methodology to better understand EBT training practices in community settings. Furthermore, it synthesized the existing training practices for community-based therapists specific to a particular EBT, PCIT. Among the participating trainers there were many similarities in training methods (e.g., incorporation of workshop training, clinical case review, consultation, and follow-up support) yet key differences in the delivery of training components, amount of detail within topics, and administration of clinical competency and skill check offs. Trainers also varied on their review of clinical cases, consultation length and methods, and follow-up support. In areas in which trainers had greater variability, general training components and subcomponents were identified and consideration was given to the number of trainers endorsing a specific practice and the existing training guidelines in order to guide the theory of current training practices and to operationalize a training protocol. Specifically, when practices or opinions varied, practices which were endorsed by more trainers or were outlined explicitly in the training guidelines were weighted more heavily for inclusion. These variations may reflect a need to tailor training to specific groups with diverse knowledge and skill sets, trainer style differences, or that our field is still sorting out what training methods will be best for training community therapists in EBTs. Collectively, the current study produced a general theory of training PCIT in community-based settings through the synthesis of current practices. In turn, this study provided a foundation to develop an extensive training protocol based on current practices of expert trainers, which has broad implications and can be empirically evaluated to allow for further understanding of the effectiveness of the current training practices of the EBT in community settings.

4.1 Limitations

Several general limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings of the current study. First, although qualitative research involving expert opinion is well accepted in the medical and mental health fields, some previous authors have highlighted the paradox of recommending consensus to make progress, suggesting that this method has the potential to hinder progress in that it does not directly promote innovation (Minas & Jorm, 2010). In the current study, we chose to report similarities and differences in expert opinion as a means of understanding the current state of clinical training practices. This approach allows current practices to serve as a model to be empirically tested with the hopes of promoting future innovation. Secondly, an iterative data collection process which would have required continuing to collect data from participants following the initial analyses was not used. This would have allowed us to further refine our conceptual model and potentially enhance the richness of the data. Third, the study sample size is smaller than what is typical for grounded theory studies. Although small, this sample includes a majority of the existing trainers in the particular EBT across the US (i.e., 78.3%). In grounded theory qualitative research, the criterion for sample size is related to saturation (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Based on the in-depth level of information provided by trainers and the limited new information shared during later interviews, we felt that saturation was achieved with the 18 participating trainers. Lastly, this study outlines a theory of training but future empirical studies will be needed to draw conclusions related to the effectiveness of specific training strategies in community settings, understand whether community-based clinicians implement PCIT in the way that they are trained, and identify what practices translate to effective treatment in community settings.

4.2 Implications for Practice

A strength of this type of study is that it yields implications for practice that are informed by psychologists with years of experience and a wealth of expertise. Training was identified as a mechanism to facilitate trainee’s continual movement towards independence with the treatment model. First, participants emphasized the importance of action-oriented strategies. In planning clinical training activities, psychologists might consider involving consumers in training demonstrations, using technology to ds that allow the ability to observe clinical services and provide immediate feedback. Psychologists might also consider including a combination of activities in their training protocols – providing multiple ways to learn. Along with this, sequencing training activities so that they increase in difficulty across training (e.g., showing, modeling, practicing, and reaching clinical competence) may best facilitate knowledge and skill development. In developing training protocols, psychologist might also consider including activities that help participants feel welcomed, valued, and comfortable. Essentially, experts mentioned how important it was for training participants to feel comfortable, which is sometimes difficult to establish given the need to provide extensive feedback.

These experts also mentioned challenges that psychologists might want to consider before they implement EBTs in community settings. Some challenges were related to the training and assessment of skill development. For example, trainers mentioned obstacles in building particular therapy skills as well as assessing clinicians’ competency in the treatment model through fair and objective methods. Trainers also identified the need to address challenges that occur at the agency level as early as possible in the implementation process. For example, clinicians often face challenges obtaining support from their agencies to help develop the space required for PCIT, order equipment, and identify adequate referral streams.

4.3 Conclusions

The study findings provide an outline about training based on expert opinion and practices. The training period includes general components of pre-training preparation, workshop training, consultation, and follow up contact. Training is largely competency based and takes a graduated path towards trainee independence. Trainers report the importance of providing action-oriented strategies, combining different activities, strategically sequencing training activities, and creating a training environment in which participants feel welcomed, valued, and comfortable. This type of comparison of the current practices of trainers provides a foundation to empirically examine training effectiveness, and in turn, contribute to the enhancement of training practices for EBTs in community-based settings.

Highlights.

Training generally consists of several components: pretraining preparation, workshop trainings, consultation, and follow up.

Collectively, training across the training period was identified as a mechanism to facilitate trainee’s continual movements towards independence with the training model.

Most trainers discussed the importance of progressing with training components based on trainee skill level.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by funding from the National Institute for Mental Health (RO1 MH095750).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

This paper was presented at the 2013 PCIT International Convention.

Contributor Information

Ashley Scudder, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

Amy D. Herschell, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

References

- ATLAS.ti. Scientific Software Development GmbH. Berlin: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- August GP, Caprio S, Fennoy I, Freemark M, Kaufman FR, Lustig RH, Montori VM. Prevention and treatment of pediatric obesity: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline based on expert opinion. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2008;93(1–2):4576–4599. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearman SK, Weisz JR, Chorpita B, Hoagwood K, Marder A, Ugueto A, Bernstein A. More practice, less preach? The role of supervision processes and therapist characteristics in EBP implementation. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2013;40(6):518–529. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0485-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beidas RS, Kendall PC. Training therapists in evidence-based practice: A critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2010;17(1):1–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Price J, Reid J, Landsverk J. Cascading implementation of a foster and kinship parent intervention. Child Welfare League of America. 2008;87(5):27–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, Sanderson WC, Shoham V, Johnson SB, Pope KS, Crits-Christoph P, McCurry S. An update on empirically validated therapies. The Clinical Psychologist. 1996;49:5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Costello JE, Jian-ping He MS, Sampson NA, Kessler RC, Merikangas KR. Services for adolescents with psychiatric disorders: 12-month data from the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent. Psychiatric Services. 2014;65(3) doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science. 2009;4(50) doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM, Funderbunk BW, Hembree-Kigin T, McNeil CB, Querido JG, Hood KK. Parent-child interaction therapy with behavior problem children: One and two year maintenance of treatment effects in the family. Child & Family Behavior Therapy. 2001;23:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM. Tailoring and adapting Parent-Child Interaction Therapy to new populations. Education and Treatment of Children. 2005;28(2):197–201. [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM, Funderburk B. PCIT: Parent-child Interaction Therapy Protocol: 2011. PCIT International, Inc.; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, Friedman RM, Wallace F. Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature. Tampa, FL: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institue, The National Implementation Research Network; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Frances A, Kahn D, Carpenter D, Frances C, Docherty J. A new method of developing expert consensus practice guidelines. American Journal of Managed Care. 1998;4(7):1023–1029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funderburk B, Chaffin M, Bard E, Shanley J, Bard D, Berliner L. Comparing client outcomes for two evidence-based treatment consultation strategies. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2014 doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.910790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funderburk B, Ware LM, Altshuler E, Chaffin MJ. Use and feasibility of telemedicine technology in the dissemination of parent-child interaction therapy. Child Maltreatment. 2008;13(4):377–382. doi: 10.1177/1077559508321483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Brookman-Frazee L, Hurlburt MS, Accurso EC, Zoffness RJ, Haine-Schlagel RA, Ganger W. Mental health care for children with disruptive behavior problems: A view inside therapists' offices. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61:788–795. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.8.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Kruse M, Aarons GA. Clinicians and outcome measurement: What's the use? The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2003;30(4):393–405. doi: 10.1007/BF02287427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotham HJ. Diffusion of mental health and substance abuse treatments: Development, dissemination, and implementation. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2004;11:160–176. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson RF, Gros KS, Davidson TM, Barr S, Cohen J, Deblinger E, Ruggiero KJ. National Trainers’ Perspectives on Challenges to Implementation of an Empirically- Supported Mental Health Treatment. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2013:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0492-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwood M, Eyberg SM. Therapist verbal behavior early in treatment: Relation to successful completion of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33(3):601–612. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3303_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK, Liao JG, Letourneau EJ, Edwards DL. Transporting efficacious treatments to field settings: The link between supervisory practices and therapist fidelity in MST programs. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31(2):155–167. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3102_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herschell AD, Capage L, Bahl A, McNeil CB. The role of therapist communication style in Parent-Child Interaction Therapy. Child & Family Behavior Therapy. 2008;30(1):13–35. [Google Scholar]

- Herschell AD, Kolko DJ, Baumann BL, Davis AC. The role of therapist training in the implementation of psychosocial treatments: A review and critique with recommendations. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:448–466. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herschell AD, McNeil CB, McNeil DW. Clinical child psychology's progress in disseminating empirically supported treatments. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2004;11(3):267–288. [Google Scholar]

- Herschell AD, McNeil CB, Urquiza AJ, McGrath JM, Zebbell NM, Timmer SG, Porter A. Evaluation of a treatment manual and workshops for disseminating, Parent-Child Interaction Therapy. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2009;36:63–81. doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0194-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagwood K, Atkins M, Ialongo N. Unpacking the black box of implementation: The next generation for policy, research and practice. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2013;40:451–455. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0512-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman Foundation. Closing the quality chasm in child abuse treatment: Identifying and disseminating best practices: Findings of the Kauffman best practices project to help children heal from child abuse. Charleston, SC: National Crime Victims Research and Treatment Center; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Conduct disorders in childhood and adolesence. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Evidence-based treatment and practice: New opportunities to bridge clinical research and practice, enhance the knowledge base, and improve patient care. American Psychologist. 2008;63(3):146–159. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.3.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landes SJ, Linehan MM. Dissemination and implementation of dialectical behavior therapy: An intensive training model. In: Barlow DH, McHugh RK, editors. Dissemination and implementation of evidence-based psychological interventions. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 187–208. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Skills training manual for borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, Barlow DH. The dissemination and implemenation of evidence-based psychological treatments: A review of the current efforts. American Psychologist. 2010;65(2):73–84. doi: 10.1037/a0018121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minas H, Jorm AF. Where there is no evidence: Use of expert consensus methods to fill the evidence gap in low-income countries and cultural minorities. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2010;4:33. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-4-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MST Services, Inc. Multisystemic Therapy. 2014 http://www.mstservices.com.

- TFC Consultants, Inc. Multidimensional Treatment Fostercare. 2014 http://www.mtfc.com.

- Nelson MM, Shanley JR, Funderbunk BW, Bard E. Therapists' attitudes toward evidence-based practices and implementation of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy. ChildMaltreatment. 2012;17(1):47–55. doi: 10.1177/1077559512436674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent-Child Interaction Therapy. PCIT International. 2011 from http://www.pcit.org/

- PCIT International. Training Guidelines for Parent-Child Interaction Therapy. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- PCIT International. Training Requirements for Certification as a PCIT Therapist. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.pcit.org/

- President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Report of the President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. 2004 Retrieved from http://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov/reports/FinalReport/toc.html.

- Reitman D, McMahon RJ. Constance "Connie" Hanf (1917-2002): The mentor and the model. Cognitive & Behavioral Practice. 2013;20(1) [Google Scholar]

- Rones M, Hoagwood K. School-based mental health services: A research review. Clinical Child & Family Psychology Review. 2000;3(4):223–241. doi: 10.1023/a:1026425104386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scudder AT, Herschell AD, McNeil CB. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy. In: Reddy LA, Files-Hall TM, Schaefer CS, editors. Empirically Based Play Interventions for Children. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sholomskas DE, Syracuse-Siewert G, Rounsaville BJ, Ball SA, Nuro KF. We don't train in vain: A dissemination trial of three strategies of training clinicians in cognitive behavioral therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(1):106–115. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus SE, Sackett DL. Using research findings in clinical practice. BMU. 1998;3(17):339–342. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7154.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A. Qualitative research for social scientists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tetzlaff JM, Chan AW, Kitchen J, Sampson M, Tricco AC, Moher D. Guidelines for randomized clinical traisl protocol content: A systematic review. Systematic Reviews. 2012;1(43):1175–1186. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-1-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetzlaff JM, Moher D, Chan AW. Developing a guidelines for clinical trial protocol content: Delphi consensus survey. Trials. 2012;13(1):176. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Public Health Service, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General. Mental health: A report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: Author; 2009. Retrieved from http:\\www.surgeongeneral.gov\library\mentalhealth\. [Google Scholar]

- Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Chinman MJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, Proctor EK, Kirchner JE. Expert recommendations for implementing change (ERIC): Protocol for a mixed methods study. Implementation Science. 2014;9(39):1–12. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-9-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsie CC, Brestan-Knight E. Using an online viewing system for Parent-Child Interaction Therapy consulting with professionals. Psychological Services. 2012;9(2):224–226. doi: 10.1037/a0026183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]