Abstract

Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) detects cytosolic DNA during virus infection and induces an antiviral state. cGAS signals by synthesis of a second messenger, cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP), which activates stimulator of interferon genes (STING). We show that cGAMP is incorporated into viral particles, including lentivirus and herpesvirus virions, when these are produced in cGAS-expressing cells. Virions transferred cGAMP to newly infected cells and triggered a STING-dependent antiviral program. These effects were independent of exosomes and viral nucleic acids. Our results reveal a way by which a signal for innate immunity is transferred between cells, potentially accelerating and broadening antiviral responses. Moreover, infection of dendritic cells with cGAMP-loaded lentiviruses enhanced their activation. Loading viral vectors with cGAMP therefore holds promise for vaccine development.

Type I interferons (IFNs) play pivotal roles in the immune response to virus infection (1). IFN expression is induced by signaling pathways activated by sensors of virus presence, including cytosolic DNA sensors (2, 3). cGAS is a cytosolic DNA sensor that signals by catalyzing the synthesis of a second messenger, cGAMP (4, 5). cGAMP binds to and activates STING (5, 6), which plays a central role in cytosolic DNA sensing by relaying signals from DNA sensors to transcription factors driving IFN gene transcription (3, 7).

DNA viruses and retroviruses trigger cGAS-dependent IFN responses in infected cells (8-15). This is thought to involve sensing by cGAS of viral DNA, leading to IFN gene transcription in the same cell where DNA detection occurred or in neighboring cells connected by gap junctions (16). However, it is conceivable that IFN induction upon virus infection could also occur independently of cGAS if the infecting virus were to incorporate and transfer the cGAMP second messenger. For example, human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) particles incorporate host molecules such as APOBEC3G (17). Given this precedent, we hypothesized that cGAMP can be packaged into virions and elicits an IFN response in newly infected cells independently of cGAS expression by the latter, allowing for potentiation of innate antiviral immunity.

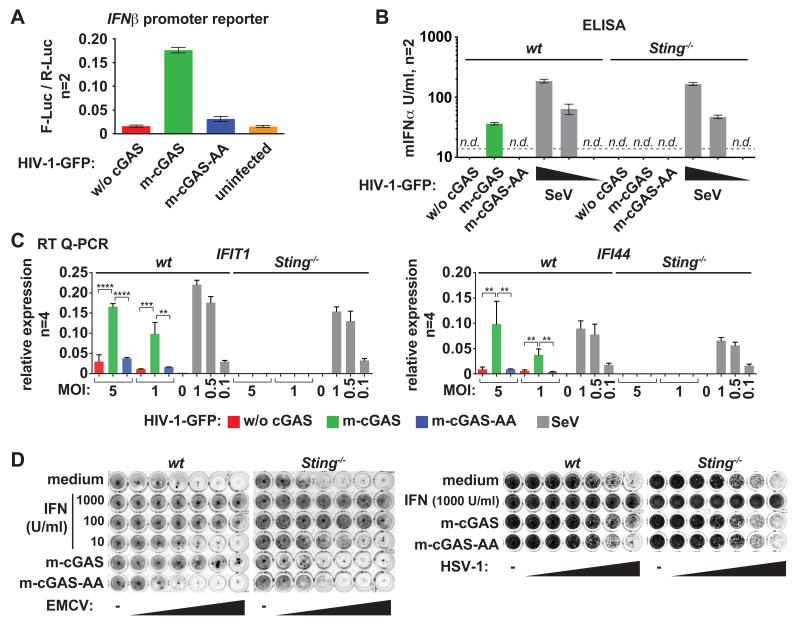

To test this idea, we produced HIV-1-based lentiviral vectors by plasmid transfection in 293T cells, a human cell line that does not express cGAS (4). Virus particles were pseudotyped with vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSV-G) and the viral genome contained enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) in the Env open reading frame. These viruses, henceforth referred to as HIV-1-GFP, are replication incompetent due to the lack of functional Env. Some 293T cells were co-transfected with expression constructs for either wild-type mouse cGAS (m-cGAS) or catalytically inactive m-cGAS-G198A/S199A (m-cGAS-AA) (4). Titrated virus stocks were then used to infect fresh HEK293 cells, which express endogenous STING (7, 18) and induce IFN in response to cGAMP (Fig. S1A-D). HIV-1-GFP collected from cGAS expressing cells triggered induction of an IFNβ promoter reporter, whereas viruses produced in the absence of exogenous cGAS or in the presence of mutant cGAS did not (Fig. 1A). Next, we analyzed IFN secretion by transferring supernatants from infected cells to a reporter cell line (HEK293-ISRE-luc), in which firefly luciferase expression is driven by interferon stimulated response elements (Fig. S1E). Only virus stocks produced in wild-type cGAS expressing cells triggered IFN secretion (Fig. S1F). Moreover, infected cells induced IFI44 and IFIT1 mRNAs specifically when cGAS was present in virus producer cells, further demonstrating induction of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) (Fig. S1G). We made similar observations when infecting the myeloid cell line THP1 (Fig. S2). Next, we infected primary mouse bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs). IFN and ISGs were induced in BMDMs infected with HIV-1-GFP produced in cGAS-reconstituted 293T cells (Fig. 1B,C). STING-deficient BMDMs did not induce IFN and ISGs in response to the same virus preparations, although RIG-I-dependent IFN production triggered by Sendai virus (SeV) was normal (Fig. 1B,C). The increased IFN production triggered by HIV-1-GFP was functionally relevant, as infection with HIV-1-GFP produced in the presence of cGAS conferred a STING-dependent antiviral state against subsequent challenge with encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) or herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

HIV-1-GFP produced in cGAS-reconstituted 293T cells induces IFN. (A) HEK293 cells were transfected with p125-F-Luc (IFNβ promoter reporter) and pRL-TK. After 6-8 hours, cells were infected (MOI=1) with HIV-1-GFP from producer cells expressing cGAS as indicated. FLuc activity was analyzed after 24 hours and normalized to R-Luc. m-cGAS-AA is a catalytically inactive mutant (N=2 biological replicates, average and individual values are shown). (B) BMDMs of the indicated genotypes were infected with HIV-1-GFP (MOI=5) or SeV (wedges: MOI=1, 0.5, 0.1). Supernatant was tested after 24 hours for mIFNα by ELISA (n.d.: not detectable; dashed line: lower limit of detection, N=2 biological replicates, average and individual values are shown). (C) BMDMs were infected as in (B) and the indicated mRNAs were quantified relative to GAPDH mRNA by RT Q-PCR (N=4 replicates; error bars indicate SD and significance was determined by ANOVA; ****, P < 0.0001; ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05). (D) Lung fibroblasts were treated with IFN-A/D or infected with HIV-1-GFP (MOI=2). Cells were then infected with EMCV or HSV-1 (wedges: 4-fold dilutions starting at MOI=4 or MOI=64, respectively). After 24 hours, cells were stained with crystal violet. Data are representative of three or more independent experiments.

To exclude the possibility that transfer of plasmid DNA or of a soluble factor accounts for IFN production by freshly infected cells, we treated virus preparations with DNase or pelleted virions by centrifugation. Neither treatment impacted the ability of HIV-1-GFP produced in cGAS expressing cells to induce IFN (Fig. S3A,B). The IFN response in target cells was independent of reverse transcription and integration, as shown by pharmacological inhibition with nevirapine and raltegravir, respectively (Fig. S3C). Virus-like particles lacking the viral RNA genome induced IFN in target cells when collected from cGAS expressing producer cells (Fig. S3D). These observations demonstrate that neither the viral genome nor its reverse transcription products account for IFN induction in this setting. Substitution of VSV-G with thogotovirus glycoprotein did not diminish the IFN inducing property of virus stocks from cGAS expressing cells, showing that these effects are not related to VSV-G pseudotyping (Fig. S3E) (19).

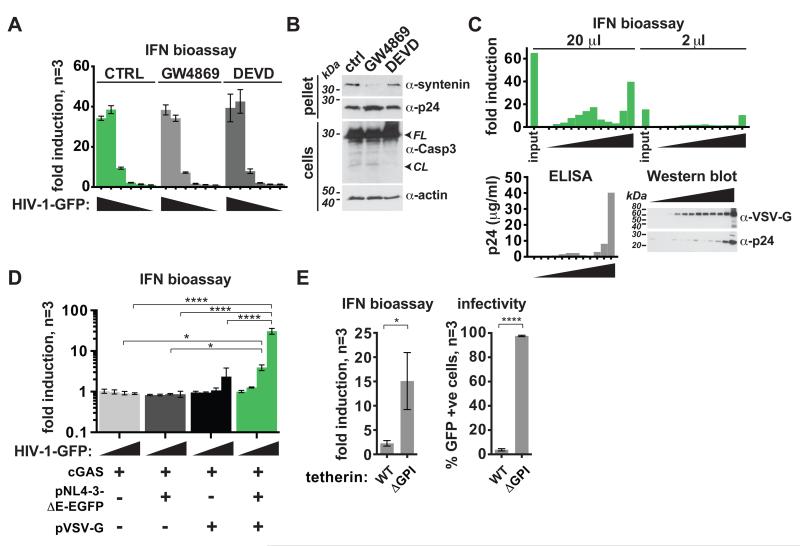

HIV-1-GFP stocks are likely to contain exosomes and other enveloped vesicles such as apoptotic bodies. Treatment of cGAS-reconstituted producer cells with the exosome inhibitor GW4869 (20) or the caspase inhibitor Ac-DEVD-CHO during virus preparation did not impact IFN induction by HIV-1-GFP (Fig. 2A). Reduced amounts of the exosome marker syntenin (21) in virus preparations and diminished cleavage of caspase 3 in virus producer cells confirmed the efficacy of these compounds (Fig. 2B). We then separated virions from exosomes and other extracellular vesicles by density gradient centrifugation (22) and found that the fraction containing the majority of the viral p24 protein and of VSV-G was also the most potent fraction inducing IFN (Fig. 2C). Next, we transfected 293T cells with cGAS plasmid alone and prepared mock “virus” stocks. These preparations did not induce detectable amounts of IFN (Fig. 2D) suggesting that vesicles constitutively shed by cells do not account for IFN induction. Moreover, overexpression of tetherin, which inhibits virion release (23), diminished IFN induction (Fig. 2E). Together, these observations show that the majority of the IFN-inducing activity is associated with virions.

Fig. 2.

IFN induction triggered by HIV-1-GFP from cGAS expressing cells is mediated by virions. (A,C-E) HEK293 cells were infected for 24 hours, washed and after additional 48 hours, secreted IFN was analyzed by bioassay. (A) HIV-1-GFP was produced in cells reconstituted with m-cGAS that were also treated with 20 μM GW4869, 60 μM Ac-DEVD-CHO or were left untreated (control). Fresh cells were infected with pelleted virus (wedges: 10-fold dilutions, N=3 biological replicates). Differences between groups were not statistically significant (ANOVA). (B) Pelleted viruses from (A) (top) or whole cell extracts (bottom) from virus producer cells were tested by Western blot. FL denotes full length and CL cleaved caspase 3. (C) HIV-1-GFP from cGAS expressing cells was loaded onto density gradients. Wedges indicate increasing iodixanol concentration in 12 collected fractions. 20 and 2 μl of each fraction and of the input were tested. p24 concentrations were determined by ELISA (bottom left) and p24 and VSV-G were analyzed by Western blot (bottom right). (D) 293T cells were transfected as indicated to produce mock “virus” stocks (wedges: 10-fold dilutions, N=3 biological replicates). (E) Vpu-deficient lentivectors produced in cells expressing cGAS and either wild type or mutant tetherin were tested. The fraction of infected cells was determined by FACS (right). N=3 biological replicates. Error bars are ±SD and significance was determined by ANOVA (A,D) or unpaired t-test (E) (****, P < 0.0001; ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05). Data are representative of two (C) or three (A,B,D,E) independent experiments.

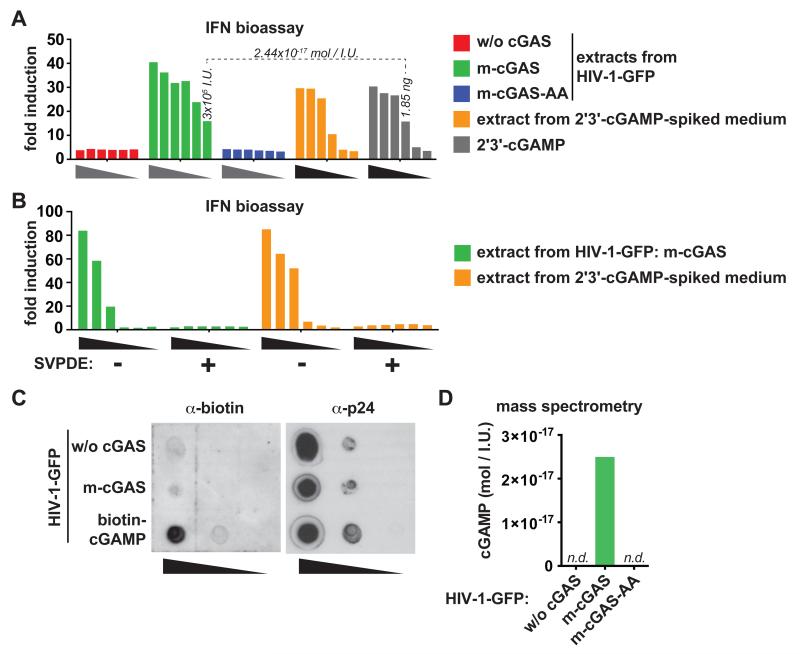

Next, we prepared small molecule extracts from HIV-1-GFP, which we then added to PMA differentiated THP1 cells that were mildly permeabilized with digitonin (Fig. S4). HIV-1-GFP extracts collected from wild-type cGAS reconstituted producer cells induced IFN secretion, while HIV-1-GFP extracts collected from catalytically inactive m-cGAS-AA reconstituted producer cells failed to induce IFN secretion (Fig. 3A). Pre-incubation of extracts with snake venom phosphodiesterase I (SVPDE), which cleaves cGAMP (24), abrogated this effect (Fig. 3B). To further test whether cGAMP is present in lentiviral particles, we transfected virus producer cells with biotin-labeled cGAMP. Biotin-cGAMP was detectable in virus preparations (Fig. 3C). Next, we quantified the amount of cGAMP present in HIV-1-GFP preparations using mass spectrometry. cGAMP was detectable only in extracts from virus produced in cGAS expressing cells (Fig. 3D). Based on a calibration curve and the efficiency of extraction (Fig. S5), we found that 2.50×10−17 mol cGAMP were present in virus stocks per infectious unit (Fig. 3D). A similar estimate was obtained from the data in Fig. 3A.

Fig. 3.

Small molecule extracts from HIV-1-GFP generated in cGAS-reconstituted producer cells induce IFN and contain cGAMP. (A) Extracts from viruses produced in the absence of cGAS or in the presence of wild-type (m-cGAS) or mutant cGAS (m-cGAS-AA) were added to digitonin permeabilized THP1 cells. IFN in THP1 supernatants was assessed by bioassay. Gray wedges represent a 1:2 dilution series starting with extract from 107 infectious units. As controls, synthetic 2′3′-cGAMP was either directly added to THP1 cells (grey bars) or was spiked into medium and then included in the extraction procedure (orange bars). Black wedges represent a 1:3 dilution series starting with 50 ng 2′3′-cGAMP. Extraction efficiency (Fig. S5B) was taken into account to estimate the amount of cGAMP per infectious unit (dotted line). (B) Extract from 107 infectious units HIV-1-GFP produced in the presence of cGAS was incubated with or without SVPDE for 1 hour and then added to digitonin permeabilized THP1 cells. IFN in THP1 supernatants was assessed by bioassay. Wedges represent a 1:3 dilution series. (C) HIV-1-GFP produced in the absence or presence of cGAS or in biotin-cGAMP transfected cells was probed by dot blot for biotin (left). The stripped membrane was re-probed for p24 (right). Wedges represent a 1:10 dilution series starting with 2×106 infectious units. (D) cGAMP concentration in samples from (A) was analyzed by mass spectrometry. n.d., not detectable. Data are representative of two (B) or three (A,C,D) independent experiments.

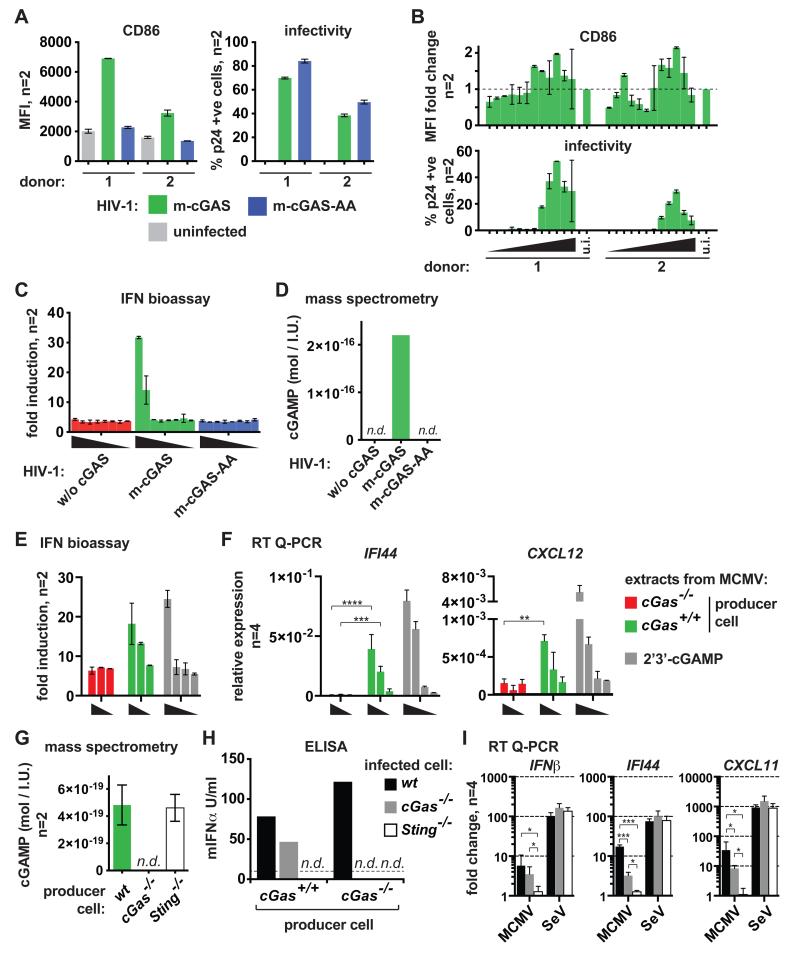

These results show that cGAMP can be packaged into HIV-1-GFP and induces IFN via STING in newly infected cells. Similarly, we found that an HIV-2-based, replication-deficient lentivirus produced in cGAS-expressing cells induced IFN secretion in HEK293 cells (Fig. S6). To further explore the relevance of our findings, we extended our study from replication-deficient, VSV-G pseudotyped lentiviruses to fully infectious HIV-1 bearing a native CXCR4-tropic envelope glycoprotein. Human monocyte-derived dendritic cells (hMDDCs) infected with HIV-1 produced in 293T cells reconstituted with wild-type cGAS induced the expression of IFN and of CD86, encoded by an ISG (Fig. 4A, S7-S9). Density gradient centrifugation demonstrated that most of the CD86-inducing activity fractionated together with infectious virus particles (Fig. 4B). Next, we prepared extracts and found that these induced IFN secretion by THP1 cells (Fig. 4C). Mass spectrometry confirmed that cGAMP was specifically present in extracts from HIV-1 stocks from cGAS expressing cells (Fig. 4D). These results show that cGAMP is not only incorporated into VSV-G pseudotyped lentivectors but can also be incorporated into fully infectious HIV-1. However, these experiments relied on overexpression of cGAS in virus producer cells. We therefore asked whether triggering of endogenous cGAS during virus infection results in the packaging of cGAMP into progeny virus particles. We used mouse cytomegalovirus (MCMV), an enveloped DNA virus, for these experiments (Fig. S10) as this virus induces STING-dependent IFN responses (25). We propagated MCMV in primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). Extracts from MCMV stocks collected from wild type cells contained an activity that induced IFN secretion and ISG expression in THP1 cells, while extracts from virus from cGAS-deficient cells did not (Fig. 4 E,F). Mass spectrometry confirmed the presence of cGAMP in MCMV stocks from wild type cells (Fig. 4G). Similarly, virus produced in Sting−/− cells contained cGAMP, while no cGAMP was detectable in virus preparations from cGas−/− cells (Fig. 4G). Consistent with this observation, MCMV produced in cGAS-sufficient MEFs induced IFNα secretion by cGas−/− BMDMs upon infection, but failed to do so in Sting−/− cells (Fig. 4H). In contrast, the response to MCMV from cGAS-deficient producer cells required both cGAS and STING. Furthermore, IFNβ, ISG and chemokine mRNA up-regulation following infection with MCMV from wild type producer cells was partially cGAS-independent but fully STING-dependent (Fig. 4I). Taken together, these results demonstrate that cGAMP produced by endogenous cGAS is incorporated into MCMV particles, which contributes to IFN induction in newly infected cells in a cGAS-independent but STING-dependent manner.

Fig. 4.

Fully infectious HIV-1 and MCMV incorporate cGAMP. (A) hMDDCs from two blood donors were infected with HIV-1 produced in the presence of wild-type (m-cGAS) or mutant cGAS (m-cGAS-AA). CD86 and p24 expression were determined by FACS; MFI = mean fluorescence intensity (N=2 infections per donor, average and individual values are shown). (B) HIV-1 produced in the presence of wild-type cGAS was fractionated on density gradients and analyzed as in (A). CD86 MFI in uninfected (u.i.) cells was set to 1 (N=2 infections per donor, average and individual values are shown). (C) Extracts from HIV-1 were tested as in Fig. 3A. wedges = 3-fold dilutions (N=2 biological replicates, average and individual values are shown). (D) 2′3′-cGAMP concentration in samples from (C) was analyzed by mass spectrometry. n.d., not detectable. (E,F) MCMV was propagated in primary MEFs of the indicated genotypes. Virus extracts or 2′3′-cGAMP were added to permeabilized THP1 cells. Secreted IFN was assessed by bioassay (E, N=2 biological replicates, average and individual values are shown) and the indicated mRNAs were quantified by RT Q-PCR relative to GAPDH mRNA (F, N=4 replicates). Wedges represent a 1:3 dilution series starting with extract from 250,000 infectious units or 0.0686 ng cGAMP. (G) cGAMP concentrations in MCMV extracts were analyzed by mass spectrometry. n.d., not detectable. Data were pooled from two independent experiments. Average and individual values are shown. (H) BMDMs of the indicated genotypes were infected with MCMV (MOI=7) from cGas+/+ or cGas−/− MEFs and supernatant mIFNα was analyzed by ELISA after 20 hours (n.d., not detectable; dashed line: lower limit of detection). (I) BMDMs as in (H) were infected with MCMV (MOI=1) from cGas+/+ MEFs for 20 hours. The indicated mRNAs were quantified by RT Q-PCR relative to GAPDH mRNA and fold changes compared to mock infected cells were calculated (N=4 replicates). SeV was used as a control (MOI=0.5). In F and I error bars indicate SD and significance was determined by ANOVA (****, P < 0.0001; ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05). Data are representative of three (A) or two (B-F,I) independent experiments.

Incorporation of cGAMP into virions may broaden the spectrum of cells that initiate an IFN response. For example, HIV-1 reverse transcription, which is inhibited in some cells by SAMHD1 (26), is not required for virus sensing via cGAMP transfer. This Trojan horse mechanism may also accelerate the IFN response. We speculate that cGAMP packaging had been overlooked in previous studies due to virus production in cGAS-negative cell lines such as 293T. Whether the incorporation of cGAMP into virus particles is a selective process or is based on diffusion remains to be determined. It is likely that a lipid envelope is required to encompass cGAMP in virus particles. Indeed, non-enveloped adenovirus produced in cGAS-reconstituted cells did not induce IFN in newly infected cells (Fig. S11). In our experimental settings, cGAMP was primarily transferred by virions; however, these data do not exclude a role of extracellular vesicles such as exosomes in shuttling cGAMP between cells in other models (for example, sterile inflammation). Although it remains unclear whether HIV virions produced during natural infection contain significant levels of cGAMP, our observations have important translational implications. cGAMP delivery via lentiviral vectors results in heightened activation of DCs (Figs. S8, S9 and S12). This could be harnessed in vaccination settings in which viral vectors co-deliver to DCs cyclic dinucleotides as innate stimuli as well as viral antigens. Moreover, IFN induction by oncolytic viruses has been reported to enhance tumor killing (27) and may be achieved by cGAMP-loading. In sum, we have identified a mechanism by which a signal for innate immunity is transferred between cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank P. Klenerman, Q. Sattentau, S. Rowland-Jones and K. James for reagents and advice, D. Gaughan, M-Y. Sun and A. Simmons for hMDDCs, A. Garbe for help with mass spectrometry and C. Reis e Sousa, V. Cerundolo, A. Armitage, G.J. Towers and J. Rasaiyaah for critical discussions. The authors thank J. Sharpe and J. Sloane-Stanley (WIMM Mouse Transgenic and Knockout Facility) for their help with re-derivation of cGas−/− mice. Mpys−/− mice and sperm from cGas−/− mice were provided by J. Cambier and EMMA, respectively, and are subject to materials transfer agreements. The data presented in this manuscript are tabulated in the main paper and in the supplementary materials. This work was funded by the UK Medical Research Council [MRC core funding of the MRC Human Immunology Unit and grant number MR/K012037 (PB)], by the Wellcome Trust, grant number 100954 (JR), and by the NIH, NIAID, grant number AI 114266 (PB). JM was a recipient of an EMBO long-term postdoctoral fellowship and was also supported by Marie Curie Actions (EMBOCOFUND2010, GA-2010-267146). A provisional patent (U.S. patent application 62/051,016) has been filed pertaining to biological applications relating to the use of cGAMP loaded viral particles.

Footnotes

References and Notes

- 1.Samuel CE. Antiviral actions of interferons. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:778–809. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.4.778-809.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pichlmair A, Reis e Sousa C. Innate recognition of viruses. Immunity. 2007;27:370–383. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paludan SR, Bowie AG. Immune Sensing of DNA. Immunity. 2013;38:870–880. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun L, Wu J, Du F, Chen X, Chen ZJ. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science. 2013;339:786–791. doi: 10.1126/science.1232458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu J, et al. Cyclic GMP-AMP is an endogenous second messenger in innate immune signaling by cytosolic DNA. Science. 2013;339:826–830. doi: 10.1126/science.1229963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gao P, et al. Structure-Function Analysis of STING Activation by c[G(2′,5′)pA(3′,5′)p] and Targeting by Antiviral DMXAA. Cell. 2013;154:748–762. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ishikawa H, Barber GN. STING is an endoplasmic reticulum adaptor that facilitates innate immune signalling. Nature. 2008;455:674–678. doi: 10.1038/nature07317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao D, et al. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is an innate immune sensor of HIV and other retroviruses. Science. 2013;341:903–906. doi: 10.1126/science.1240933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jakobsen MR, et al. IFI16 senses DNA forms of the lentiviral replication cycle and controls HIV-1 replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:E4571–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311669110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lahaye X, et al. The capsids of HIV-1 and HIV-2 determine immune detection of the viral cDNA by the innate sensor cGAS in dendritic cells. Immunity. 2013;39:1132–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rasaiyaah J, et al. HIV-1 evades innate immune recognition through specific cofactor recruitment. Nature. 2013;503:402–405. doi: 10.1038/nature12769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dai P, et al. Barry M, editor. Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara Triggers Type I IFN Production in Murine Conventional Dendritic Cells via a cGAS/STING-Mediated Cytosolic DNA-Sensing Pathway. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1003989. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schoggins JW, et al. Pan-viral specificity of IFN-induced genes reveals new roles for cGAS in innate immunity. Nature. 2014;505:691–695. doi: 10.1038/nature12862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lam E, Stein S, Falck-Pedersen E. Adenovirus detection by the cGAS/STING/TBK1 DNA sensing cascade. J Virol. 2014;88:974–981. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02702-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li X-D, et al. Pivotal roles of cGAS-cGAMP signaling in antiviral defense and immune adjuvant effects. Science. 2013;341:1390–1394. doi: 10.1126/science.1244040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ablasser A, et al. Cell intrinsic immunity spreads to bystander cells via the intercellular transfer of cGAMP. Nature. 2013;503:530–534. doi: 10.1038/nature12640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malim MH. APOBEC proteins and intrinsic resistance to HIV-1 infection. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci. 2009;364:675–687. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burdette DL, et al. STING is a direct innate immune sensor of cyclic di-GMP. Nature. 2011;478:515–518. doi: 10.1038/nature10429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pichlmair A, et al. Tubulovesicular structures within vesicular stomatitis virus G protein-pseudotyped lentiviral vector preparations carry DNA and stimulate antiviral responses via Toll-like receptor 9. J Virol. 2007;81:539–547. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01818-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li J, et al. Exosomes mediate the cell-to-cell transmission of IFN-α-induced antiviral activity. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:793–803. doi: 10.1038/ni.2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baietti MF, et al. Syndecan-syntenin-ALIX regulates the biogenesis of exosomes. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:677–685. doi: 10.1038/ncb2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dettenhofer M, Yu XF. Highly purified human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reveals a virtual absence of Vif in virions. J Virol. 1999;73:1460–1467. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1460-1467.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Neil SJD. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology, Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Vol. 371. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2013. pp. 67–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ablasser A, et al. cGAS produces a 2′-5′-linked cyclic dinucleotide second messenger that activates STING. Nature. 2013;498:380–384. doi: 10.1038/nature12306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun C, et al. Evasion of Innate Cytosolic DNA Sensing by a Gammaherpesvirus Facilitates Establishment of Latent Infection. The Journal of Immunology. 2015;194:1819–1831. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laguette N, Benkirane M. How SAMHD1 changes our view of viral restriction. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang L-CS, et al. Treating tumors with a vaccinia virus expressing IFNβ illustrates the complex relationships between oncolytic ability and immunogenicity. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2012;20:736–748. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang H, et al. Novel single-cell-level phenotypic assay for residual drug susceptibility and reduced replication capacity of drug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2004;78:1718–1729. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.4.1718-1729.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neil SJD, Zang T, Bieniasz PD. Tetherin inhibits retrovirus release and is antagonized by HIV-1 Vpu. Nature. 2008;451:425–430. doi: 10.1038/nature06553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manel N, et al. A cryptic sensor for HIV-1 activates antiviral innate immunity in dendritic cells. Nature. 2010;467:214–217. doi: 10.1038/nature09337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rehwinkel J, et al. SAMHD1-dependent retroviral control and escape in mice. EMBO J. 2013;32:2454–2462. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rehwinkel J, et al. RIG-I detects viral genomic RNA during negative-strand RNA virus infection. Cell. 2010;140:397–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jin L, et al. MPYS is required for IFN response factor 3 activation and type I IFN production in the response of cultured phagocytes to bacterial second messengers cyclic-di-AMP and cyclic-di-GMP. The Journal of Immunology. 2011;187:2595–2601. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakagata N. Cryopreservation of mouse spermatozoa and in vitro fertilization. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;693:57–73. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-974-1_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seluanov A, Vaidya A, Gorbunova V. Establishing primary adult fibroblast cultures from rodents. JoVE. 2010 doi: 10.3791/2033. doi:10.3791/2033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woodward JJ, Iavarone AT, Portnoy DA. c-di-AMP secreted by intracellular Listeria monocytogenes activates a host type I interferon response. Science. 2010;328:1703–1705. doi: 10.1126/science.1189801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.