Abstract

Bacterial biofilms infect 2 – 4 % of medical devices upon implantation, resulting in multiple surgeries and increased recovery time due to the very great increase in antibiotic resistance in the biofilm phenotype. This work investigates the feasibility of thermal mitigation of biofilms at physiologically accessible temperatures. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms were cultured to high bacterial density (1.7 × 109 CFU cm−2) and subjected to thermal shocks ranging from 50 °C to 80 °C for durations of 1 to 30 min. The decrease in viable bacteria was closely correlated with an Arrhenius temperature dependence and Weibull-style time dependence, demonstrating up to six orders of magnitude reduction in bacterial load. The bacterial load for films with more conventional initial bacterial densities dropped below quantifiable levels, indicating thermal mitigation as a viable approach to biofilm control.

Keywords: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, biofilm, infection, heat shock, implanted medical device

Introduction

Each year over 3.6 million medical devices are surgically implanted in the US, with 150,000 (4%) becoming infected (Darouiche 2004). Adding dental implants and catheters, these numbers increase by an order of magnitude (Ehrlich et al. 2005). These infections are particularly difficult to treat and typically require explantation and replacement of the device (Darouiche 2004, Hedrick et al. 2006, Vinh and Embil 2005). The resulting increased hospitalization, additional surgical procedures, and replacement medical devices drive the cumulative cost of these device-related nosocomial (hospital-acquired) infections over five billion dollars per year (Burke 2003, Darouiche 2004). This figure does not include patient loss of productivity and quality of life, or the impact of the thousands of patients who do not survive their infections. Consequently, a great deal of effort is devoted to preventing nosocomial infections, from rigid protocols for hand-washing and sterilization to prophylactic antibiotic regimens for weeks prior to surgery. Despite these efforts infection rates remain high, with the number of nosocomial infections holding steady over a 20-year span while hospital patient-days decreased 30% (Burke 2003, Jarvis 2001). Moreover, the infection rate for the replacement device is higher than for the original. For example, 1.5-2.5% of total hip and knee replacements develop joint infections upon primary implantation. After replacement, the rates increase to 3.2-5.6% (Lentino 2003).

These infections are typically caused by bacteria which colonize the device surface and surround themselves in an extracellular matrix of polysaccharides, forming a biofilm. Bacteria in biofilms exhibit a markedly different phenotype from planktonic (ie free-floating) bacteria, including a substantial increase in antibiotic resistance (Nickel et al. 1985, Vinh and Embil 2005), effectively negating the primary clinical approach of antibiotic administration for bacterial infection. The extracellular polymeric substance (EPS)can act as a transport barrier to larger antimicrobial agents (Drenkard 2003, Fux et al. 2003) and act as a reactive sink for oxidizing agents (Chang and Craik 2012, Chen and Stewart 1996), protecting the cells deeper in the film. However, it has become clear that obstruction of biocide transport is not the only resistance mechanism associated with biofilms. In many cases, transport of oxygen and nutrients is also limited, with available oxygen being depleted in the top 50 μm of the biofilm (Borriello et al. 2004, Drenkard 2003, Fux, Stoodley, Hall-Stoodley and Costerton 2003, Werner et al. 2004). As aerobic metabolism drops, the internal activity of the antimicrobial agents also drops, rendering many agents much less effective. Resistance may also derive from the significant difference in the regulation of genes in the biofilm. Further complicating matters, the biofilm may host multiple species of pathogens, each with different resistance characteristics (Stoodley et al. 2002, Watnick and Kolter 2000). These biofilm-specific resistance problems suggest an inherent limit on the effectiveness of strictly chemical approaches to biofilm eradication.

At the device level, most effort has been devoted to prevention, creating device surfaces which prevent bacteria from colonizing (Carlson et al. 2008, Cheng et al. 2007, Kingshott and Griesser 1999, Mi and Jiang 2014). A variety of anti-adhesive polymer coatings have demonstrated decreased bacterial adhesion in vitro, though these surfaces may be fouled by other chemical species in vivo and it is unclear that any decrease short of zero adhesion will be sufficient to prevent biofilm formation (von Eiff et al. 2005). Alternatively, the surface may contain an antimicrobial agent to kill adhering bacteria before they can switch to their more robust biofilm phenotype (Smith 2005, Sreekumari et al. 2003, Tamilvanan et al. 2008, von Eiff, Jansen, Kohnen and Becker 2005). This requires more careful formulation to constantly guarantee a local concentration sufficient to quickly kill all bacteria without harming the patient. It also requires that none of the potential colonizing bacteria have a resistance to the antimicrobial agent. As the prevalence of resistant bacteria increases, the chances of success by this approach decreases.

Once a biofilm infection is established, treatment options are more limited. A variety of techniques including electrical currents (Blenkinsopp et al. 1992, Jass and Lappin-Scott 1996, van der Borden et al. 2003), ultrasound (Carmen et al. 2005), extracorporeal shock waves (Gerdesmeyer et al. 2005), quorum-sensing peptides (Boles and Horswill 2008, Davies et al. 1998, Kalia 2013) and photodynamic therapy (Di Poto et al. 2009, Wood et al. 2006) have been investigated without advancing to clinical tests. Concerns with these approaches include an insufficient in vitro effect, insufficient breadth of susceptible pathogens and difficulty of in vivo implementation. At present, patients with infected devices are still treated with strong antibiotic regimens, typically followed by explantation and eventual replacement of the device (Darouiche 2004, von Eiff, Jansen, Kohnen and Becker 2005). This is often done in multiple stages, where explantation is followed by weeks or months (Moran et al. 2010) of antibiotic treatment before re-implantation of a device. Even with these precautions, the incidence of infection in the replacement device is higher than for the original one (Darouiche 2004).

Thermal treatment of biofilms may prove to be a more universally effective approach. Pasteurization protocols have been used at a variety of temperatures for over a century, and thermal sterilization of biofilms at temperatures >120 °C on medical and food processing equipment is also standard. Surprisingly little is known, however, about the cell viability of bacterial biofilms at more accessible temperatures (<80 °C). One group has developed a predictive model for heat inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes biofilms on food processing equipment at 70 to 80 °C (Chmielewski and Frank 2004, 2006), and another briefly studied heating effects on Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms when dosing them with superparamagnetic nanoparticles (Park et al. 2011). In this communication, the authors report the systematic investigation of bacterial biofilm cell death at temperatures ranging from 50 to 80 °C for exposure times ranging from 1 to 30 min. In conjunction with the development of a composite coating which can generate these temperatures precisely at the implant surface using an alternating magnetic field, this work aims to develop a new approach to mitigating biofilm infections on medical implants.

Materials and methods

Organism and inoculum

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is commonly associated with nosocomial infections and its biofilm has been extensively investigated (Drenkard and Ausubel 2002, Gellatly and Hancock 2013). P. aeruginosa reference strain PAO1 (16952, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) was used for the current study. This strain is non-mucoidal and representative of typical P. aeruginosa found in a nosocomial setting. For each trial, the bacterium was isolated from frozen glycerol stock cultures and streaked on an agar-filled plate (Difco Nutrient Agar, Sparks, MD). The streaked plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C, and then a single colony was used to inoculate 5 ml of tryptic soy broth (TSB). Prior to inoculation, TSB was autoclaved at 121 °C and cooled to room temperature. The inoculum was incubated at 37 °C in a sealed culture tube. Initially, 1 ml samples were removed periodically over the course of 36 h and quantified via direct enumeration as described below in order to characterize the inoculum growth curve. The inoculum for the heat shock trials was incubated at 37 °C for 24 h.

Media

Tryptic soy broth (TSB, BD Bacto, Sparks, MD) was obtained as a dry powder and dissolved in a ratio of 30 g l−1 of deionized water by heating in a 700 W microwave for 10 min. It was autoclaved at 121 °C and cooled to room temperature prior to use. The components for the glucose-enhanced medium were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA), consisting of 5.232 g of MOPS free acid, 4.3 g of potassium monophosphate, 2.7 g of potassium phosphate dibasic, 24 mg of magnesium sulfate and 1.44 mg of ferrous sulfate heptahydrate in 500 ml of deionized water. This medium was vacuum filtered to ensure sterility.

Biofilm culture

Shaker-plate biofilms

Single-side, fully-frosted microscope slides were placed individually on the bottom of each well in a 4-well polystyrene rectangular dish (Thermo Scientific Nunc, Rochester, NY). 0.33 ml of P. aeruginosa inoculum were added to 5 ml of glucose-enhanced medium in each well. The dishes were sealed with parafilm and placed on an orbital shaker (15 mm orbit diameter) at 150 rpm for 72 h in a 37 °C incubator, producing biofilms with an average bacterial density of 2.66 × 106 CFU cm−2.

Drip flow reactor biofilms

Biofilms were cultured in a 4-channel drip flow reactor (DFR, Biosurface Technologies Corporation, Bozeman, MT) according to ASTM standard E2647-08. Briefly, a single-side, fully-frosted glass microscope slide was placed in each channel along with 15 ml of TSB and 1 ml of inoculum. The reactor was incubated at 37 °C for 4 h, followed by tilting the channels by 10° in the longitudinal direction so that the medium would drain from the channel. Fresh medium was constantly dripped on the raised end of the slide at a rate of 1.25 l day−1channel−1, administered by a four-channel peristaltic pump (MasterFlex L/S, Cole-Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL) for 24 h, producing thick, uniform biofilms with an average bacterial density of 1.65 × 109 CFU cm−2.

Thermal Shock

To expose the biofilms to a uniform, precise temperature for a defined time period, thermal shock was performed by immersion in pre-heated water. A polystyrene 4-well plate was filled with 5 ml of water per well, covered, sealed in parafilm, and submerged in a thermostatted water bath (Isotemp 3013P, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) to preheat the water and the plate. Each well contained two type T thermocouples by which the well temperatures were recorded throughout the trial. Slides from the biofilm reactor were quickly transferred into the plate, one per well, and the plate was resealed and submerged for the prescribed thermal exposure time. The microscope slides with the biofilms were then transferred out of the thermal shock plate into a polystyrene 4-well plate with 5 ml well−1 of fresh medium at room temperature and immediately quantified. Shaker-plate biofilms were thermally shocked at 50 and 80 °C, along with a 37 °C control, at exposure times of 2, 10, and 30 min. DFR biofilms were thermally shocked at temperatures of 50, 60, 70, and 80 °C in addition to 37 °C controls, with exposure times of 1, 2, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 30 min at each temperature. A minimum of three multi-biofilm trials were performed on each time/temperature combination, with replicates occurring on separate days in random order.

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM)

The thickness and architectural characteristics of the biofilms were evaluated using CLSM. In this technique, light from a single focal plane is collected; by stepping through multiple focal planes, a 3-D image of the sample is generated. Fluorescent dyes from a LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability Kit (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) were used for imaging. The dyes are based on membrane integrity, with SYTO 9 entering all cells and fluorescing green when complexed with DNA. Propidium iodide enters only cells with disrupted membranes, quenching SYTO 9 and fluorescing red when complexed with DNA. Stained biofilms were analyzed using an upright Bio-Rad 1024 confocal microscope with Kr/Ar lasers emitting at 488 and 568 nm to excite SYTO 9 and propidium iodide, respectively. Images were collected by scanning the entire sample area with one laser and collecting the resulting fluorescent light, followed by a scan using the other laser to minimize the effect of excitation/emission overlap. Each recorded image is the average of four sets of scans, recording a 512 × 512 pixel array with 256 intensity levels. Samples were imaged through a 40x water-immersion lens in 1 μm vertical increments. Subsequent image analysis was performed using the Java-based, public domain image processor, ImageJ (ImageJ 2015).

Quantification via direct enumeration

While microscopy allows rapid analysis and determination of the spatial distribution of bacteria within the biofilm, its quantification limits for biofilm bacterial load are modest. To quantify the reduction in viable bacteria over multiple orders of magnitude direct enumeration was used. The polystyrene 4-well plate containing thermally shocked biofilms, each in 5 ml of fresh, room-temperature medium was sealed and placed in a 45 kHz sonication bath (VWR 9.5L, Radnor, PA) for 10 min to disrupt the polysaccharide matrix and homogenize the bacteria into the medium. After sonication, a 100 μl sample was taken from each well and serially diluted by factors of 10 across several culture tubes. 100 μl samples from each culture tube were spread across agar-filled Petri dishes using glass beads, then incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Duplicate dilutions and plating were performed for every biofilm. Following incubation, the numbers of colonies on each agar plate were counted. The logarithm of the CFU concentration in the biofilm was then calculated using Equation 1:

| (1) |

where the plate count is the number of colonies on a particular plate and the dilution factor is the factor by which the original 100 μl sample was diluted before being spread across the agar plate. Only plate counts between 5 and 150 were used; in instances where more than one plate in a dilution series met this criterion, the one with the lower dilution factor was used.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using JMP 11.2 statistical software. Means comparisons were performed using a one-way ANOVA Tukey-Kramer method with α = 0.05. Average log (CFU cm−2) values are arithmetic averages of all log (CFU cm−2) values for all samples from a given time/temperature thermal shock combination, with the corresponding standard deviation (SD).

Results

Growth study

Incubated at 37 °C, the lag phase for P. aeruginosa was less than 2 h, followed by an exponential growth phase plateauing approximately 24 h after inoculation. The bacterial concentration from 24 to 36 h post-inoculation was constant at 1.6 (+/− 0.2) × 109 CFU ml−1 (n = 7).

Shaker plate biofilms

Biofilms cultured on a shaker plate in glucose-enhanced medium were thin (25-50 μm) and variegated. Figure 1 shows a visual comparison of shaker-plate and drip-flow-reactor biofilms using CLSM. In all, 48 biofilms underwent the thermal shock process at the control temperature of 37 °C (ie no actual temperature change) with 16 at each of three exposure times: 2, 10, and 30 min. The average log (CFU cm−2) across all trials was 6.24 (0.48 SD), with no significant effect of exposure time. Average log (CFU cm−2) were 6.29 (0.48 SD), 6.15 (0.55 SD), and 6.28 (0.48 SD) for 2, 10, and 30 min exposures, respectively. These results are summarized graphically in Figure S1 of the Supplemental material.

Figure 1.

CLSM control biofilms. Live bacteria fluoresce green and dead bacteria fluoresce red. Shaker biofilms (A) were ~25 to 45 μm thick with patchy coverage over the microscope slide, while DFR biofilms (B) were 50 to 150 μm thick with dense coverage over the entire slide.

Sixty three biofilms were thermally shocked at 80 °C, 21 at each of three exposure times: 2, 10, and 30 min. The resulting bacteria concentrations were below the quantification limit in most instances (data not shown). Only 6 of the 21 biofilms exposed at 80 °C for 2 min had at least 13.3 CFU cm−2 (log(CFU cm−2) = 1.12). At exposure times of 10 and 30 min, the number of quantifiable biofilms dropped to 3 and 1, respectively. In 9 of the 21 biofilms exposed for 30 minutes, no CFUs were detected.

DFR biofilms

Biofilms cultured in drip flow reactors were thicker (50-150 μm) and more carpetlike, as shown in Figure 1. Moreover, their bacterial concentrations were much higher, permitting quantification of the large CFU reductions observed after thermal shock of the shaker plate biofilms. Ninety-six control biofilms were thermally ‘shocked’ at 37 °C (ie no actual temperature change) for exposure times of 1, 2, 5, 10, 15, 20, or 30 min. Their average log (CFU cm−2) following this treatment was 8.56 (0.66 SD), 2.3 orders of magnitude larger than the shaker-plate biofilms, again with no apparent dependence on exposure time. These results are summarized graphically in Figure S2.

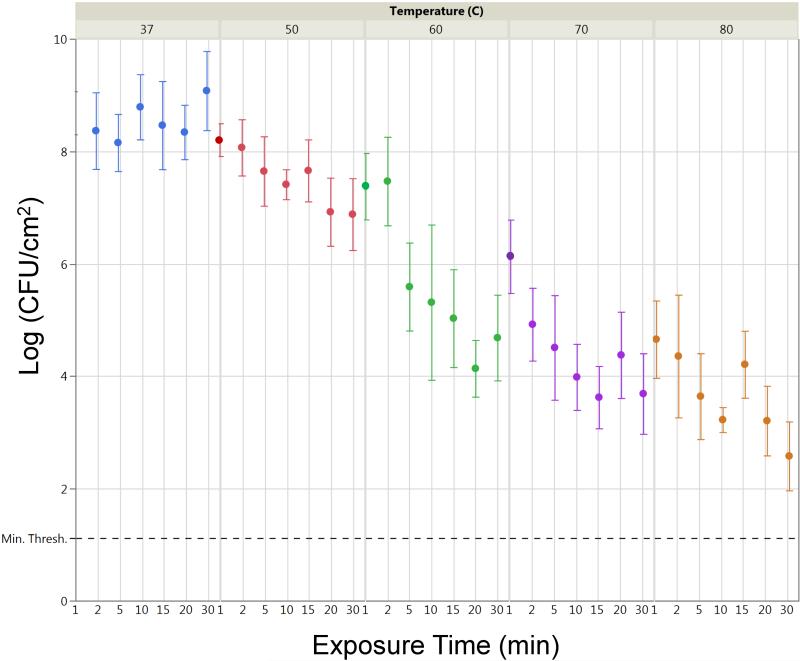

Table 1 lists the average log (CFU cm−2) at each temperature/exposure time combination, with a minimum of 9 biofilms per combination and an average n = 13.6 biofilms. CFU reductions of up to six orders of magnitude are observed, with CFU cm−2 concentrations still well above the quantification limit, as indicated in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Average log(CFU cm-2) for biofilm thermal shock experiments.

| Thermal shock Temp. (°C) |

Exposure time (min) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 30 | |

| 37 | 8.68 ± 0.38 | 8.37 ± 0.68 | 8.15 ± 0.51 | 8.79 ± 0.58 | 8.46 ± 0.78 | 8.34 ± 0.48 | 9.08 ± 0.70 |

| 50 | 8.21 ± 0.29 | 8.07 ± 0.50 | 7.65 ± 0.62 | 7.41 ± 0.27 | 7.66 ± 0.55 | 6.92 ± 0.61 | 6.88 ± 0.64 |

| 60 | 7.38 ± 0.59 | 7.47 ± 0.79 | 5.59 ± 0.78 | 5.32 ± 1.38 | 5.03 ± 0.87 | 4.14 ± 0.50 | 4.69 ± 0.76 |

| 70 | 6.13 ± 0.65 | 4.92 ± 0.65 | 4.51 ± 0.93 | 3.99 ± 0.59 | 3.63 ± 0.55 | 4.38 ± 0.77 | 3.69 ± 0.72 |

| 80 | 4.66 ± 0.69 | 4.36 ± 1.09 | 3.64 ± 0.76 | 3.23 ± 0.22 | 4.21 ± 0.60 | 3.21 ± 0.62 | 2.58 ± 0.61 |

Heat shocks at 37°C were comparable controls. As heat shock temperature or exposure time increases, the average log(CFU cm−2) decreases. SDs (n ≥ 9) are indicated with ±. Bright red cells indicate large CFU densities while bright blue cells indicate low CFU densities.

Figure 2.

Average log(CFU cm−2) of thermally shocked DFR biofilms as a function of temperature and exposures time. Error bars indicate SDs of log(CFU cm−2) averages (n ≥ 9). Dashed line indicates a minimum quantification limit of 1.12.

Discussion

A wide variety of approaches to biofilm mitigation have been investigated, with most reporting CFU decreases of 1-2 orders of magnitude. For instance ozone has reduced biofilm populations by two orders of magnitude (Chang and Craik 2012), and oral plaque biofilms have been reduced by two orders of magnitude using photodynamic therapy (Wood, Metcalf, Devine and Robinson 2006), but like many other approaches it is unclear how these would be implemented in situ.

Thermal biofilm mitigation, however, demonstrated CFU reductions of up to six orders of magnitude, necessitating the use of biofilms with much higher initial bacterial loads in order to fully quantify the reduction. The shaker plate biofilms in this study had bacterial loads averaging log (CFU cm−2) = 6.24 (ie nearly two million CFU cm−2). At 80 °C, however, the bacterial load often dropped below the quantification limit, even at short exposure times. The quantification limit was set to keep a single CFU from altering the calculated bacterial concentration by >20%. Hence the plate count in Equation 1 must be at least five. Homogenizing an entire 18.75 cm2 biofilm into 5 ml of mediim and plating 100 μl of the suspension on an agar plate, at least 13.3 CFU cm−2 (log(CFU cm−2 = 1.12) must be present to produce five colonies on average. With this quantification limit, the shaker plate films could demonstrate at best (6.24 – 1.12 =) a 5.12 orders of magnitude reduction in bacterial load. In practice, the observable range is smaller as any variability would otherwise push some results below the quantification limit. To fully quantify the reduction in log (CFU cm−2), drip flow reactor biofilms (with initial log (CFU cm−2) of 8.56) were required, though this load may be much higher than in a typical clinical infection.

Regarding in situ implementation, there are a variety of means for delivering heat at the precise location of the biofilm infection. One approach is to coat the implant with a magnetically susceptible composite. Any biofilm colonizing the implant would be in direct contact with the coating, which could apply the necessary temperature wirelessly on demand from an external alternating magnetic field. Magnetic nanoparticle / polymer composite coatings capable of achieving 80 °C in 15 s under static tissue have recently been reported (Coffel and Nuxoll 2015). As with pasteurization of planktonic bacteria, a continuum of temperature and exposure time combinations can be used to achieve a target CFU reduction (FDA 2011). To interpolate the combination that will achieve the CFU reduction while minimizing damage to adjacent tissue, clear understanding of each parameter’s role is needed. This paper aims to assist in that understanding.

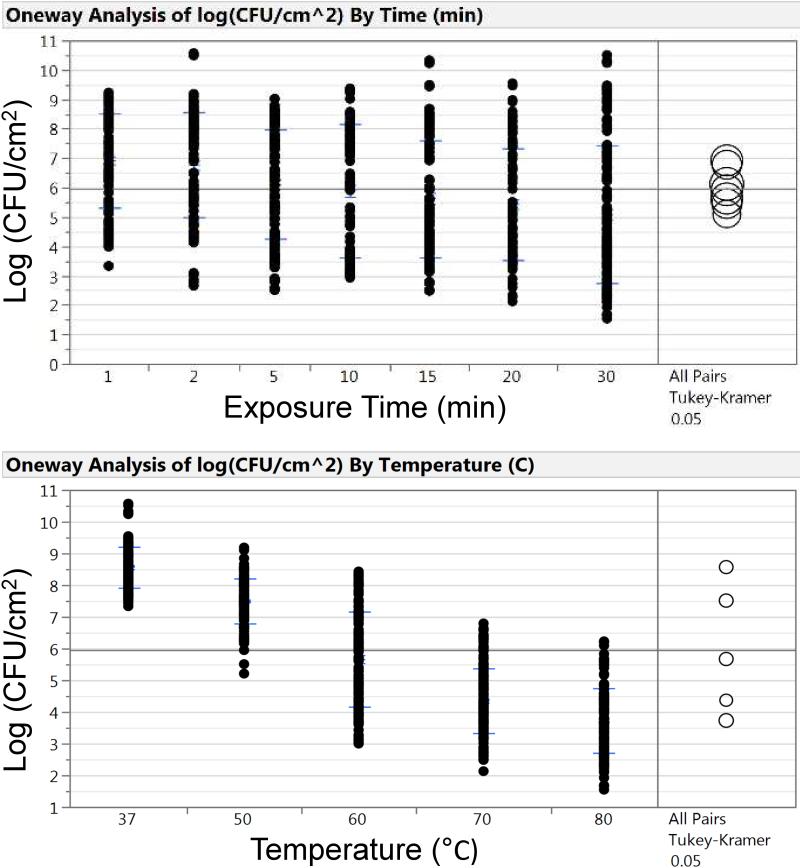

Table 1 indicates that increasing either the exposure time or temperature decreased log (CFU cm−2). However, increasing the temperature had a much larger impact than increasing the time over the range investigated. Comparing the means using a one-way ANOVA Tukey-Kramer method showed that the effect of exposure time on the resulting log (CFU cm−2) was not statistically different or significant (Figure 3A), while the same means comparison on temperature vs log (CFU cm−2) shows a statistical difference (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Analysis of exposure time (A) and temperature (B) on log(CFU cm−2). Exposure time and temperature are both important when reducing log(CFU cm−2). However, one-way ANOVA mean comparison using the Tukey-Kramer method (alpha = 0.05) shows there is a larger significant difference with regards to temperature than time.

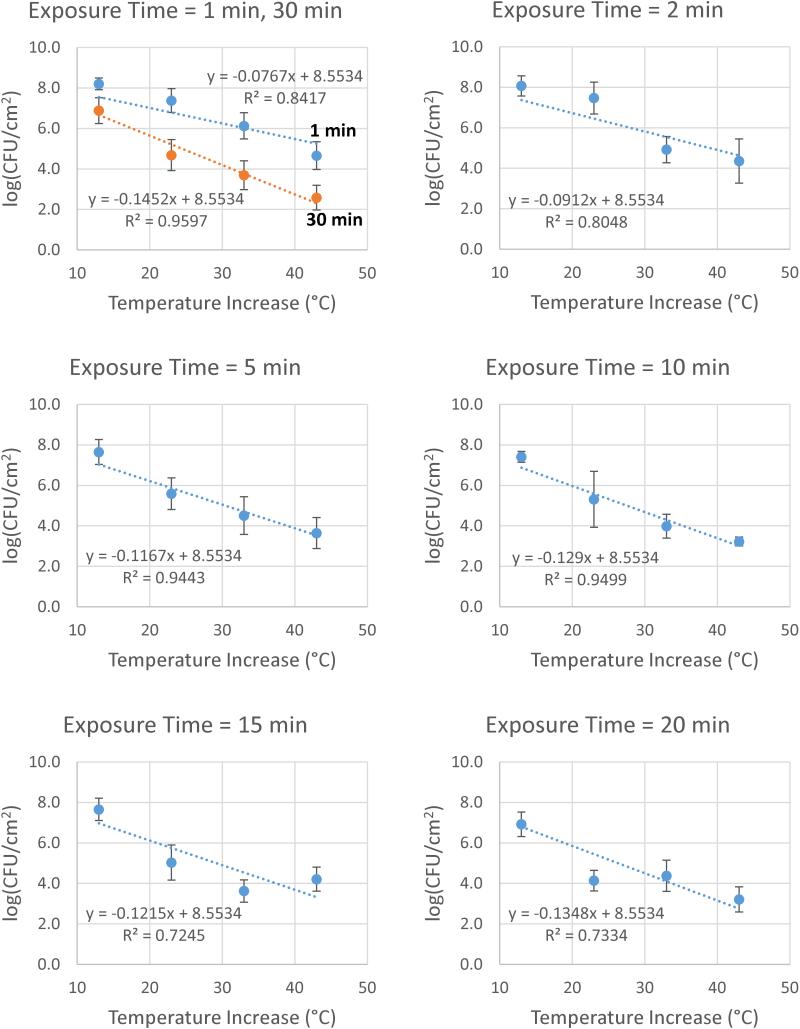

Correlation with temperature increase

Correlating the results with an analytical expression yields a similar conclusion. Linear regressions of log (CFU cm−2) vs the temperature increase at each exposure time yield tight correlations with r2 values > 0.92 for all but two exposure times. Moreover, the deviations from linearity do not follow a clear trend suggesting any mathematical modification to the linear relationship, as shown in Figures S3-S9. The intercepts of these regressions, however, should equal the log (CFU cm−2) of the control experiments, where the temperature increase is zero. Pinning the intercepts of these regressions to the overall average control log (CFU cm−2) of 8.553, the regressions maintain an average r2 value of 0.85 as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Correlation of log(CFU cm−2) with temperature increase. Post-thermal-shock CFU density on a log scale shows good linear correlation with temperature increase, even with trendlines pinned to an intercept of 8.5534 to match the overall average control log(CFU cm−2). Error bars indicate SDs.

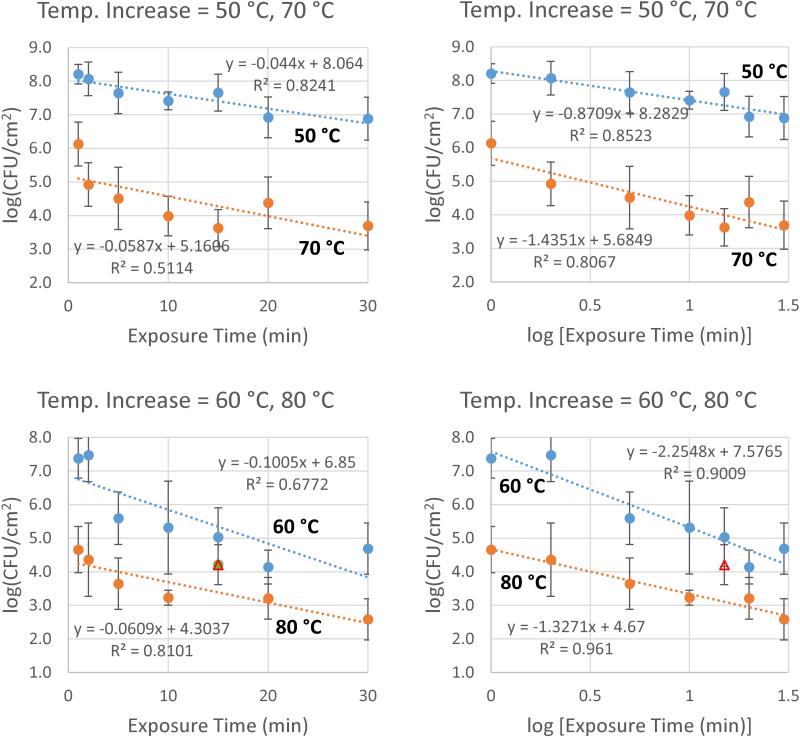

Correlation with exposure time

The relationship between log (CFU cm−2) and exposure time does not appear to be best represented by a linear expression. Figure 5 compares linear correlations (left-hand-side) with logarithmic correlations (right-hand-side), indicating that log (CFU cm−2) more closely correlates with log (exposure time) than with exposure time directly. One datum (80 °C, 15 min) is over a SD away from both the linear and logarithmic trendlines, and therefore has been excluded from the analysis to provide a clearer comparison. When included, the logarithmic correlation is still closer than the linear one. CFU cm−2

Figure 5.

Correlation of log(CFU cm−2) with exposure time.Post-thermal-shock CFU density on a log scale shows a better correlation with log (exposure time) (right) than with exposure time directly (left). Triangular point at 80 °C, 15 min is excluded from analysis for clarity; when included r2 values are 0.6572 (linear regression) and 0.6741 (log regression).

Combined correlation with temperature increase and exposure time

Figure 4 correlates log (CFU/cm−2) to temperature increase in the form

| (2) |

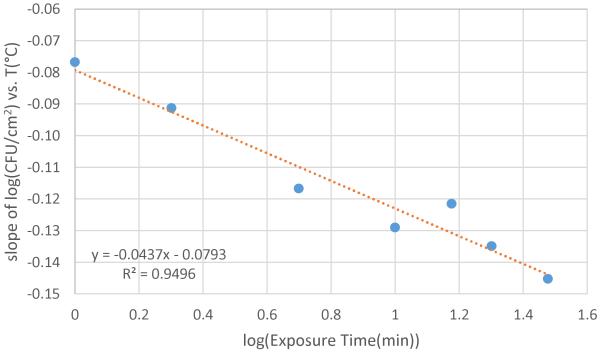

where log(CFU/cm−2)0 is the overall average control value at 37 °C of 8.553 and T is the thermal shock temperature in °C. The slopes from these regressions at each exposure time are compiled in Table 2. Plotting these slopes vs log (exposure time), a clear linear relationship is seen (Figure 6) with an r2 of 0.95.

Table 2.

Slopes of [log(CFU cm−2) vs temperature increase] shown in Figure 4.

| Exposure time (min) | Slope | r2 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | −0.0767 | 0.9852 |

| 2 | −0.0912 | 0.9238 |

| 5 | −0.1167 | 0.9574 |

| 10 | −0.1290 | 0.9555 |

| 15 | −0.1215 | 0.7255 |

| 20 | −0.1348 | 0.7843 |

| 30 | −0.1452 | 0.9620 |

Compiling slopes of linear trendlines from Figure 4 reveals a correlation with exposure time.

Figure 6.

Correlation of cell death temperature dependence to log(exposures time).

Using the slope and intercept from Figure 6, an analytical expression for log (CFU cm−2) as a function of thermal shock temperature and exposure time is determined:

| (3) |

where T is the thermal shock temperature in °C and t is the exposure time. Equation 3 may also be expressed:

| (4) |

which more clearly shows a modified Arrhenius dependence on temperature. However, not only is there no discernable lag time in cell death, the relationship to exposure time follows a Weibull-style relationship (Juneja et al. 2006), while planktonic bacterial death is traditionally modeled with a linear relationship between log (CFU cm−2) and time (Moats 1971). Moreover, the thermal shock temperature affects even this relationship, with higher temperatures prompting a stronger time dependence not just as a coefficient but also as an exponent. Figure 5 demonstrates that log(CFU cm−2) is much more linearly related to log(t) than to t.

Comparing each experimental result from Table 1 with the corresponding calculation from Equation 3, it can be seen that Equation 3 predicts the experimental log (CFU cm−2) with an accuracy exceeding the precision of the experimental measurements. The difference between the calculated and experimental log (CFU cm−2) values are shown in Table S2. In all but nine instances (highlighted in Table S2), the calculation from Equation 3 is within one SD of the experimental mean.

Implications

For thermal mitigation of medical implant infections, thermal shock can be applied directly by the substratum on which the biofilm is growing. While the maximum temperature will be experienced by the biofilm itself, heat will likely conduct into the surrounding tissue and damage it. This damage should be viewed in the context, however, of the current treatment, which is explantation surgery and removal of the surrounding tissue, followed by reimplantation surgery with a higher degree of infection. Besides all the other disadvantages to this treatment (for example extended hospitalization, time without a needed medical device, loss of alignment markers for joint implants) the tissue damage from the current treatment is significant. Importantly, the presence of a coating which can supply a thermal shock does not commit the patient to using thermal mitigation if an infection is diagnosed; it would only be applied if it were deemed better than the alternatives.

To determine an appropriate exposure protocol and make that decision, the effects of both temperature and exposure time must be understood. Standard conduction of heat into the surrounding tissue depends linearly on the applied temperature, and decreases with the square root of time as the penetration distance increases. As the cell death relationship expressed in Equation 3 has a larger dependence on temperature and a smaller dependence on time, these results indicate that to minimize damage to the surrounding tissue while achieving a set degree of bacterial death, higher temperatures at lower exposure times may be preferred. Investigations on whether antibiotics may decrease the thermal shock required to achieve a set degree of bacterial death are ongoing.

There are also many instances beyond the field of medicine where biofilm mitigation is necessary but conventional ex situ treatments such as autoclaving are not viable. Plastics with glass transition temperatures <120 °C cannot be autoclaved, and may have surfaces inaccessible to UV light or antimicrobial chemicals. The current work provides a framework for thermally mitigating these biofilms at more accessible temperatures.

Conclusions

Infection of newly implanted medical devices by bacterial biofilms is a severe problem with no immediate solution. The increased chemical resistance of bacteria in biofilms, along with the continued evolutionary resistance of bacteria in general, make chemical approaches problematic. Similarly, the diverse chemical environment of the body has confounded material-based approaches to non-fouling surfaces. Thermal shock of bacterial biofilms, however, can reduce their populations by six orders of magnitude at temperatures not exceeding 80 °C. The decrease in cell viability in P. aeruginosa bacterial biofilms has been experimentally determined for temperatures ranging from 50 to 80 °C and exposure times ranging from 1 to 30 min. These results have been correlated with an analytical expression which on average calculates the resulting bacterial loading to within a factor of three across the entire parameter space. The results indicate temperature has a larger effect than exposure time on biofilm cell death. With the development of implant coatings which can provide on-demand heating directly at the infection site, thermal mitigation should be a viable treatment strategy for medical implant infections.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the American Heart Association (11SDG7600044) and the National Science Foundation (CBET-1133297). E. Ricker was supported by the Predoctoral Training Program in Biotechnology from the National Institute for General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (T32GM008365). A. O’Toole was supported by a training grant from the Iowa Center for Biocatalysis and Bioprocessing, also associated with the above NIGMS NIH Predoctoral Training Program in Biotechnology. The content of this material is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the supporting agencies.

This work was supported by the American Heart Association under Grant 11SDG7600044; the National Science Foundation under Grant CBET-1133297; and the National Institute for General Medical Sciences, NIH under Grant 5T32GM008365.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest related to this work.

7. References

- Blenkinsopp SA, Khoury AE, Costerton JW. Electrical enhancement of biocide efficacy against Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1992;58:3770–3773. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.11.3770-3773.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boles BR, Horswill AR. agr-mediated dispersal of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. PLoS Pathogens. 2008;4:1–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borriello G, Werner E, Roe F, Kim AM, Ehrlich GD, Stewart PS. Oxygen limitation contributes to antibiotic tolerance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in biofilms. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2004;48:2659–2664. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.7.2659-2664.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JP. Infection Control - a problem for patient safety. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;348:651–656. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr020557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson RP, Taffs R, Davison WM, Stewart PS. Anti-biofilm properties of chitosan-coated surfaces. Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition. 2008;19:1035–1046. doi: 10.1163/156856208784909372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmen JC, Roeder BL, Nelson JL, Ogilvie RL, Robison RA, Schaalje GB, Pitt WG. Treatment of biofilm infections on implants with low-frequency ultrasound and antibiotics. American Journal of Infection Control. 2005;33:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Craik S. Laboratory Simulation of the Effect of ozone and monochloramine on biofilms in drinking water mains. Ozone: Science & Engineering. 2012;34:243–251. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Stewart PS. Chlorine penetration into artificial biofilm is limited by a reaction-diffusion interaction. Environmental Science & Technology. 1996;30:2078–2083. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng G, Zhang Z, Chen S, Bryers JD, Jiang S. Inhibition of bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation on zwitterionic surfaces. Biomaterials. 2007 Oct;28:4192–4199. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski RAN, Frank JF. A predictive model for heat inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes biofilm on stainless steel. Journal of Food Protection. 2004;67:2712–2718. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-67.12.2712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmielewski RAN, Frank JF. A predictive model for heat inactivation of Listeria monocytogenes biofilm on buna-N rubber. LWT Food Science and Technology. 2006;39:11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Coffel J, Nuxoll E. Magnetic nanoparticle / polymer composites for medical implant infection control. Advanced Healthcare Materials. 2015 doi: 10.1039/c5tb01540e. (submitted; placeholder) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darouiche RO. Treatment of infections associated with surgical implants. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;350:1422–1429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies DG, Parsek MR, Pearson JP, Iglewski BH, Costerton JW, Greenberg EP. The involvement of cell-to-cell signals in the development of a bacterial biofilm. Science. 1998;280:295–298. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5361.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Poto A, Sbarra MS, Provenza G, Visai L, Speziale P. The effect of photodynamic treatment combined with antibiotic action or host defence mechanisms on Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Biomaterials. 2009;30:3158–3166. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenkard E. Antimicrobial resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Microbes and Infection. 2003;5:1213–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenkard E, Ausubel FM. Pseudomonas biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance are linked to phenotypic variation. Nature. 2002;416:740–743. doi: 10.1038/416740a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich GD, Stoodley P, Kathju S, Zhao Y, McLeod BR, Balaban N, Hu FZ, Sotereanos NG, Costerton JW, Stewart PS, et al. Engineering approaches for the detection and control of orthopaedic biofilm infections. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2005;437:59–66. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200508000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fux CA, Stoodley P, Hall-Stoodley L, Costerton JW. Bacterial biofilms: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy. 2003;1:667–683. doi: 10.1586/14787210.1.4.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellatly SL, Hancock RE. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: new insights into pathogenesis and host defenses. Pathogens and disease. 2013;67:159–173. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerdesmeyer L, von Eiff C, Horn C, Henne M, Roessner M, Diehl P, Gollwitzer H. Antibacterial effects of extracorporeal shock waves. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2005;31:115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2004.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrick TL, Adams JD, Sawyer RG. Implant-associated infections: an overview. Journal of Long-Term Effects of Medical Implants. 2006;16:83–99. doi: 10.1615/jlongtermeffmedimplants.v16.i1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [accessed May 19, 2015];Image Processing and analysis in Java. Available from imagej.nih.gov/ij/

- Jarvis WR. Infection control and changing health-care delivery systems. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2001;7:170–173. doi: 10.3201/eid0702.010202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jass J, Lappin-Scott HM. The efficacy of antibiotics enhanced by electrical currents against Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 1996;38:987–1000. doi: 10.1093/jac/38.6.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juneja VK, Huang L, Marks H. Advances in Microbial Food Safety: ACS Symposium Series. 2006. Approaches for modeling thermal inactivation of foodborne pathogens; pp. 235–251. [Google Scholar]

- Kalia VC. Quorum sensing inhibitors: an overview. Biotechnology Advances. 2013;31:224–245. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingshott P, Griesser HJ. Surfaces that resist bioadhesion. Current Opinion in Solid State and Materials Science. 1999;4:403–412. [Google Scholar]

- Lentino JR. Prosthetic joint infections: bane of orthopedists, challenge for infectious disease specialists. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2003;36:1157–1161. doi: 10.1086/374554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi L, Jiang S. Integrated antimicrobial and nonfouling zwitterionic polymers. Angewandte Chemie. 2014;53:1746–1754. doi: 10.1002/anie.201304060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moats WA. Kinetics of thermal death of bacteria. Journal of Bacteriology. 1971;105:165–171. doi: 10.1128/jb.105.1.165-171.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran E, Byren I, Atkins BL. The diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infections. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2010;65(Suppl 3):iii45–54. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickel JC, Ruseska I, Wright JB, Costerton JW. Tobramycin resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells growing as a biofilm on urinary catheter material. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1985;27:619–624. doi: 10.1128/aac.27.4.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H, Park HJ, Kim JA, Lee SH, Kim JH, Yoon J, Park TH. Inactivation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01 biofilms by hyperthermia using superparamagnetic nanoparticles. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2011;84:41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AW. Biofilms and antibiotic therapy: is there a role for combating bacterial resistance by the use of novel drug delivery systems? Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2005;57:1539–1550. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sreekumari KR, Nandakumar K, Takao K, Kikuchi Y. Silver containing stainless steel as a new outlook to abate bacterial adhesion and icmrobiologically influenced corrosion. ISIJ International. 2003;43:1799–1806. [Google Scholar]

- Stoodley P, Sauer K, Davies DG, Costerton JW. Biofilms as complex differentiated communities. Annual Review of Microbiology. 2002;56:187–209. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.56.012302.160705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamilvanan S, Venkateshan N, Ludwig A. The potential of lipid- and polymer-based drug delivery carriers for eradicating biofilm consortia on device-related nosocomial infections. Journal of Controlled Release. 2008;128:2–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Food and Drug Administration Grade “A” Pasteurized Milk Ordinance. 2011.

- van der Borden AJ, van der Mei HC, Busscher HJ. Electric-current-induced detachment of Staphylococcus epidermidis strains from surgical stainless steel. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B, Applied Biomaterials. 2003;68:160–164. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.20015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinh DC, Embil JM. Device-related infections: a review. Journal of Long-Term Effects of Medical Implants. 2005;15:467–488. doi: 10.1615/jlongtermeffmedimplants.v15.i5.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Eiff C, Jansen B, Kohnen W, Becker K. Infections associated with medical devices. Drugs. 2005;65:179–214. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200565020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watnick P, Kolter R. Biofilm, city of microbes. Journal of Bacteriology. 2000;182:2675–2679. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.10.2675-2679.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner E, Roe F, Bugnicourt A, Franklin MJ, Heydorn A, Molin S, Pitts B, Stewart PS. Stratified growth in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2004;70:6188–6196. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.10.6188-6196.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood S, Metcalf D, Devine D, Robinson C. Erythrosine is a potential photosensitizer for the photodynamic therapy of oral plaque biofilms. The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2006;57:680–684. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.