Abstract

Background

Our objective was to examine differences in hospital resource utilization for children with Down syndrome by age and the presence of other birth defects, particularly severe and non-severe congenital heart defects (CHDs).

Methods

This was a retrospective, population-based, statewide study of children with Down syndrome born 1998-2007, identified by the Florida Birth Defects Registry (FBDR) and linked to hospital discharge records for 1-10 years after birth. To evaluate hospital resource utilization, descriptive statistics on number of hospitalized days and hospital costs were calculated. Results were stratified by isolated Down syndrome (no other coded major birth defect); presence of severe and non-severe CHDs; and presence of major FBDR-eligible birth defects without CHDs.

Results

For 2,552 children with Down syndrome, there were 6,856 inpatient admissions, of which 68.9% occurred during the first year of life (infancy). Of the 2,552 children, 31.7% (n=808) had isolated Down syndrome, 24.0% (n=612) had severe CHDs, 36.3% (n=927) had non-severe CHDs, and 8.0% (n=205) had a major FBDR-eligible birth defect in the absence of CHD. Infants in all three non-isolated DS groups had significantly higher hospital costs compared to those with isolated Down syndrome. From infancy through age 4, children with severe CHDs had the highest inpatient costs compared to children in the other sub-groups.

Conclusions

Results support findings that for children with Down syndrome the presence of other anomalies influences hospital use and costs, and children with severe CHDs have greater hospital resource utilization than children with other CHDs or major birth defects without CHDs.

Keywords: Down syndrome; congenital heart defect; cost, hospital; birth defects surveillance

INTRODUCTION

Down syndrome, also known as trisomy 21, occurs in approximately 1 in 700 births (Parker et al., 2010). Down syndrome is often associated with impaired speech, hearing, and vision capabilities, and most individuals have impaired cognitive ability. In addition, approximately half of all individuals with Down syndrome also have a congenital heart defect (CHD) (Boulet et al., 2008; Freeman et al., 1998). Direct costs associated with Down syndrome include costs to the health care system, caregiver and psychosocial services, special education, loss of time from work, and out-of-pocket expenses for services, equipment and appliances not covered by insurance.

In a study conducted using the 2004 MarketScan Commercial claims database, researchers examined medical care expenditures for children ages birth through four years with and without Down syndrome in a privately insured population (Boulet et al., 2008). In this study, the mean and median expenditures for children with Down syndrome were 12 to 13 times higher than for children without Down syndrome and did not vary by age (Boulet et al., 2008). In addition, researchers found mean and median expenditures to be higher for children with Down syndrome and a CHD than for children with Down syndrome without a CHD, but this varied by age; the ratio of median expenditures was 6.9 in infancy, 2.4 at ages one to two, and 1.3 at ages three to four (Boulet et al., 2008). While these studies provide important information on hospital resource utilization for young children with Down syndrome, few studies have examined hospitalizations and costs beyond the first few years of life (Baraona et al., 2013; Geelhoed et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2013). Additionally, although costs associated with CHD-related hospital admissions vary widely by specific condition, studies of costs or expenditures associated with Down syndrome and CHDs do not generally stratify by CHD type (Boulet et al., 2009).

We hypothesize that hospital resource utilization is positively associated with the severity of the CHD among children with Down syndrome, and that this difference may vary by the child’s age. Our objective was to use population-based data to examine differences in hospital resource utilization for children with Down syndrome by age and the presence of other congenital anomalies, particularly severe and non-severe CHDs.

METHODS

Study population

This was a statewide, population-based, retrospective, observational study of children with Down syndrome born January 1, 1998, through December 31, 2007, identified by the Florida Birth Defects Registry (FBDR). The FBDR is a passive, statewide, population-based surveillance system that identifies infants with birth defects, such as Down syndrome, from multiple databases of health care information (National Birth Defects Prevention Network, 2011; Salemi et al., 2010; Salemi et al., 2011). Infants in the FBDR are ascertained during the first year of life, primarily using hospital discharge records from Florida’s Agency for Health Care Administration (AHCA) (Agency for Health Care Administration, 2011). The FBDR does not capture information on adopted infants, prospective adoptees, or on infants whose mothers delivered out-of-state (Salemi et al., 2010; Salemi et al., 2011). Infants included in this study were born to mothers who were residents of Florida at the time of delivery, had an International Classification of Disease, 9th revision; Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code in the FBDR for Down syndrome (758.0) and had at least one inpatient discharge record.

Longitudinal data linkage

Historically, the FBDR datasets included birth and infancy death vital records linked to AHCA inpatient and outpatient visits during the first year of life for infants identified as having at least one FBDR-eligible ICD-9-CM code (Salemi et al., 2010; Salemi et al., 2011). As part of a collaborative project with the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, University of South Florida, Florida Department of Health, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a subset of FBDR infants with specific birth defects, including Down syndrome, was linked to AHCA discharge records beyond the first year of life. The longitudinal data for this project included inpatient admissions that were initiated between January 1, 1999, and December 31, 2008, thereby capturing up to 10 years of post-infancy hospital discharge records. Data linkage was conducted using a stepwise deterministic strategy, with linking stages constructed in a hierarchical order, ranging from highest to lowest confidence. For example, stage one consisted of an exact match between infant social security number (SSN), maternal SSN, infant’s date of birth, and infant’s sex. Subsequent stages included linkages based on less exact matching of infant and/or maternal SSN; crossover matching between infant, maternal, and paternal SSN; and “fuzzy” matching on date of birth (e.g., one or two day variability in infant’s date of birth, month and day are reversed, or day and month digits are reversed). Linking passes were run without replacement; when a link was established during a given stage, the record was then removed from the pool of available records to be linked during subsequent, lower-confidence stages. Linkage was conducted separately for singleton and multiple births due to the increased complexity of linking records for multiple births. Further details of this stepwise deterministic strategy previously have been described (Salemi et al., 2013a).

Hospitalizations and costs

We estimated the number of hospital admissions, number of hospitalized days, and hospital costs based on hospitalizations initiated, but not necessarily completed, during the periods of interest. From birth through age two, we examined hospitalizations in one year intervals (i.e., infancy, age one, and age two). During the infancy period, we also examined resource utilization during the birth hospitalization and post-birth hospitalizations. Inpatient admissions that occurred between three years old through eight years old were examined over two year intervals due to decreasing numbers of children with inpatient admissions in the older age groups. Because of the small sample size of nine and ten-year-old children with inpatient admissions, we did not report these results. Multiple admission records were merged into one if a hospital transfer occurred (Colvin and Bower, 2009). Transfers were defined as inpatient admissions that occurred on the same day that the child was discharged from a previous hospitalization or admissions one day after a previous discharge with an accompanying “transfer” code.

All dollar values are reported as 2012 US dollars calculated using the Producer Price Index for hospitals (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2013). We converted inpatient charges to estimated costs using year-specific statewide cost-to-charge ratios. Based on state-level data from the AHRQ Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project State Inpatient Database, the average all-payer inpatient hospital cost-to-charge ratio among Florida hospitals ranged from 0.355 in 2001 (n=209 hospitals reporting) to 0.294 in 2008 (n=217 hospitals reporting), suggesting hospitals’ costs averaged approximately 29%-36% of the amount those hospitals billed to healthcare payers during this time period (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2013). Because 2001 was the earliest year of data available, the cost-to-charge ratio for 2001 (0.355) was also used to convert inpatient charges to estimated costs for the years 1998-2000.

Case classification

Results were stratified by isolated Down syndrome, severe CHDs, non-severe CHDs, and major FBDR-eligible birth defects without CHDs. We reviewed ICD-9-CM codes present in the database and made database-specific decisions regarding classification when multiple defect codes were present. Isolated Down syndrome was defined as having no other ICD-9-CM code for any major birth defect. Down syndrome with severe CHDs, with or without major non-cardiac defects, was defined by the presence of an ICD-9-CM code between 745.00-747.92 and catheterization (ICD-9 codes: 37.21-37.23, 88.42-88.44, 88.50-88.58) or surgical (ICD-9 codes: 35.00-35.04, 35.10-35.14, 35.20-35.28, 35.31-35.35, 35.39, 35.41, 35.42, 35.50-35.54, 35.60-35.63, 35.70-35.73, 35.81-35.84, 35.91-35.95, 35.98, 35.99, 36.99, 37.33, 37.5, 37.51, 37.52, 39.0, 39.21) procedure codes or death during the first year of life (Mahle et al., 2009). Down syndrome with all other CHDs, with or without major non-cardiac defects, was classified as Down syndrome with non-severe CHDs. Down syndrome with major FBDR-eligible birth defects without CHDs was defined by the presence of any major ICD-9-CM code included in the FBDR, other than those identified as CHD codes.

Variable construction and statistical analysis

Selected maternal demographic characteristics of interest were: age, race/ethnicity, nativity, parity, marital status, and education, along with two healthcare variables: principal expected healthcare payer at delivery and birth hospital nursery level (I, III, or III [highest]) (American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn, 2004). Private payer included private or employer-based insurance, including Tricare. Public insurance included Medicare, Medicaid, and other state and local government insurance in Florida, such as the State’s Children’s Health Insurance Program, KidCare. The birth hospital nursery level was coded as the highest level in the facility (e.g., a hospital with Level II and III beds was classified as Level III). Child demographics of interest included sex, preterm birth, birth weight, plurality, and death during infancy and childhood.

Demographic characteristics for children with Down syndrome and severe and non-severe CHDs, with or without non-cardiac defects, and children with major FBDR-eligible birth defects without CHDs were compared to children with isolated Down syndrome. Mantel-Haenszel chi-square statistics were used to compare group differences for each characteristic of interest. Costs and number of hospitalized days were presented as mean (with standard deviation) and median (with interquartile range) estimates for the infancy period; median (with interquartile range) estimates only were reported for the period beyond infancy because the follow-up time varied for children beyond one year of age. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to detect differences in hospital resource utilization by Down syndrome sub-group.

RESULTS

We identified 2,715 children with ICD-9-CM codes indicating Down syndrome in the FBDR and born 1998-2007, with an estimated administrative birth prevalence of 12.7 per 10,000 live births (n=2,715/2,135,000) (Florida Department of Health Birth, Florida Birth Defects Registry, 2011). Approximately 6.0% (n=163) did not have at least one inpatient discharge record and were excluded, resulting in a final sample size of 2,552. Children excluded from the analysis were more likely to have isolated Down syndrome, Hispanic mothers, foreign-born mothers, and were more likely to be twins or higher order multiples than children included in the analysis.

Among the 2,552 children included in the study, 808 (31.7%) had isolated Down syndrome, 612 (24.0%) had Down syndrome with a severe CHD, 927 (36.3%) had Down syndrome with a non-severe CHD, and 205 (8.0%) had Down syndrome with a major birth defect in the absence of any CHD. Approximately 80.8% (n=1,911/2,366) of children with Down syndrome and available birth hospital discharge records had an ICD-9-CM for Down syndrome on their birth hospital discharge record. Of the remaining children, 13.2% (n=388) and 4.1% (n=104) had their first ICD-9-CM code for Down syndrome on post-birth hospital discharge records during infancy and after the child’s first birthday, respectively, and 7.8% (n=199) did not have an ICD-9-CM code for Down syndrome on any hospital discharge record. Among children with multiple admissions, 87.5% (n=1,258/1,437) had an ICD-9-CM code for Down syndrome on at least two admissions; among those that only had one ICD-9-CM code for Down syndrome, the code was present on the subsequent admission for approximately 50.3% of these children (n=90/179).

Approximately 5.0% (n=126) of all children with Down syndrome died during infancy. Of these infants, 76 (60.3%) died in the hospital, with a median of 4 days hospitalized (range 0-156 days) prior to death. An additional 2.2% (n=55) of children died in the period from age one through the end of the study period, December 31, 2008, with the mortality rate ranging from 0.9% of children one year old (n=23/2,426) to 0.2% of children seven years old (n=3/875); no eight-year-old children in this cohort died. Of the children that died after infancy, 20 (36.4%) died in the hospital, with a median of 12 days hospitalized (range 0-32 days) prior to death. The most common cause of death was Down syndrome (n=44, 24.3%), followed by atrioventricular septal defect (n=14, 7.7%) and Tetralogy of Fallot (n=13, 7.2%).

The distributions of several maternal and infant characteristics were significantly different when comparing children with Down syndrome and CHDs or other major FBDR-eligible birth defects and children with isolated Down syndrome (Table 1). In comparison to mothers of children with isolated Down syndrome, mothers of children with Down syndrome and non-severe CHDs were more likely to be older than 35, of Hispanic ethnicity, and foreign-born. Children with Down syndrome and major birth defects without CHDs or with severe CHDs were more likely to be born low birth weight, and children with Down syndrome major FBDR-eligible birth defects without CHDs were more likely to have been born preterm compared to children with isolated Down syndrome. Children with Down syndrome and severe CHDs, non-severe CHDs, and other major FBDR-eligible birth defects without CHDs were more likely to have been born in a hospital with level III nursery care. The mortality rate during the study period was three times higher for children with Down syndrome and severe CHDs and almost twice as high for children with Down syndrome and other major FBDR-eligible birth defects without CHDs compared to children with isolated Down syndrome. Children with isolated Down syndrome were twice as likely to die during the study period as children Down syndrome and with non-severe CHDs, although, by definition, infants with CHDs that died during infancy were considered to have severe CHDs.

Table 1.

Selected demographic characteristics for Florida-born children with Down syndrome, 1998-2007

| Down syndrome case classification |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All children (n=2,552) |

Isolateda (n=808) |

Severe CHDsb (n=612) |

Non-severe CHDsb (n=927) |

Other major FBDRc- eligible birth defects without CHDsb (n=205) |

|

|

| |||||

| Parent/ household | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Mother’s age, years | |||||

| < 20 | 172 (6.7) | 66 (8.2) | 41 (6.7) | 49 (5.3)* | 16 (7.8) |

| 20-24 | 393 (15.4) | 126 (15.6) | 107 (17.5) | 128 (13.8) | 32 (15.6) |

| 25-29 | 384 (15.1) | 141 (17.5) | 95 (15.5) | 121 (13.1) | 27 (13.2) |

| 30-34 | 508 (19.9) | 165 (20.4) | 116 (19.0) | 175 (18.9) | 52 (25.4) |

| 35-39 | 655 (25.7) | 183 (22.7) | 147 (24.0) | 272 (29.3) | 53 (25.9) |

| ≥ 40 | 440 (17.2) | 127 (15.7) | 106 (17.3) | 182 (19.6) | 25 (12.2) |

| Mother’s race / ethnicity | |||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 1,288 (50.4) | 432 (53.5) | 333 (54.4) | 422 (45.5)* | 101 (49.3) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 514 (20.1) | 147 (18.2) | 134 (21.9) | 185 (20.0) | 48 (23.4) |

| Hispanic | 668 (26.2) | 201 (24.9) | 130 (21.2) | 292 (31.5) | 45 (22.0) |

| Asian / Pacific Islander and American Indian / Alaskan | 60 (2.4) | 20 (2.5) | 11 (1.8) | 19 (2.1) | 10 (4.9) |

| Other or unknown | 22 (0.9) | 8 (1.0) | 4 (0.7) | 9 (1.0) | 1 (0.5) |

| Mother’s nativity, foreign-born | 829 (32.5) | 249 (30.8) | 174 (28.4) | 339 (36.6)* | 67 (32.7) |

| Mother’s parity, nulliparous | 807 (31.7) | 266 (32.9) | 203 (33.2) | 271 (29.3) | 67 (32.7) |

| Mother’s education | |||||

| Less than high school graduate | 471 (18.5) | 164 (20.3) | 107 (17.5) | 160 (17.3) | 40 (19.5) |

| High school graduate or equivalent |

807 (31.6) | 236 (29.2) | 211 (34.5) | 295 (31.8) | 65 (31.7) |

| At least some college or university |

1,255 (49.2) | 404 (50.0) | 288 (47.1) | 467 (50.4) | 96 (46.8) |

| Unknown | 19 (0.7) | 4 (0.5) | 6 (1.0) | 5 (0.5) | 4 (2.0) |

| Principal healthcare payer at birthd | |||||

| Private | 1,312 (55.5) | 421 (56.4) | 307 (54.6) | 489 (56.4) | 95 (49.7) |

| Public | 940 (39.7) | 283 (37.9) | 227 (40.4) | 344 (14.5) | 86 (45.0) |

| Self/underinsured/charity | 114 (4.8) | 42 (5.6) | 28 (5.0) | 34 (3.9) | 10 (5.2) |

| Birth hospital nursery care level | |||||

| I | 535 (21.0) | 217 (26.9) | 108 (17.7)* | 160 (17.3)* | 50 (24.4)* |

| II | 693 (27.2) | 253 (31.3) | 140 (22.9) | 254 (27.4) | 46 (22.4) |

| III | 1,300 (51.0) | 333 (41.2) | 354 (57.8) | 504 (54.4) | 109 (53.2) |

|

| |||||

| Child | |||||

|

| |||||

| Sex, female | 1,186 (46.5) | 372 (46.0) | 312 (51.0) | 416 (44.9) | 86 (42.0) |

| Preterm birth (20-36 weeks) | 664 (26.1) | 193 (24.0) | 164 (26.9) | 241 (26.0) | 66 (32.4)* |

| Low birth weight (<2,500 g) | 535 (21.0) | 140 (17.3) | 156 (25.4)* | 183 (19.7) | 56 (27.3)* |

| Plurality, singleton | 2,503 (98.1) | 793 (98.1) | 595 (97.2) | 914 (98.6) | 201 (98.1) |

| Death during infancy | 126 (4.9) | 30 (3.7) | 81 (13.2)* | 0 (0.0) | 15 (7.3)* |

| Death during study period | 181 (7.1) | 39 (4.8) | 101 (16.5)* | 22 (2.4)* | 19 (9.3)* |

Notes. Percentages may not sum to 100% due to missing data.

Distribution significantly different than isolated Down syndrome, p<0.05.

Isolated Down syndrome = no International Classification of Disease, 9th revision; Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code for any other major birth defect present in Florida Birth Defects Registry;

CHD = congenital heart defect;

FBDR= Florida Birth Defects Registry;

Private insurance includes employer-based insurance (including Tricare). Public insurance includes Medicare, Medicaid, and other state and local government insurance in Florida, such as the State’s Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) KidCare.

There were a total of 6,856 inpatient admissions during the study period, 4,724 (68.9%) of which were initiated during the first 12 months of life. Approximately 14.0% (n=368) of infants experienced a hospital transfer at birth; an additional 61 infants (n=2.4%) experienced a transfer at a later time. During the first year of life, infants were hospitalized an average of 20.5 days (standard deviation [SD]: 32.4) with a mean estimated inpatient cost of $41,568 (SD: $84,572) (Table 2). Mean estimated inpatient costs during the first year of life for infants with severe CHDs were approximately 11 times the mean estimated inpatient costs for isolated Down syndrome; median costs for infants with severe CHDs were more than 26 times the median costs for infants with isolated Down syndrome. Mean and median estimated inpatient costs were two and four times higher for infants with Down syndrome and non-severe CHDs and four and six times higher for infants with Down syndrome and major FBDR-eligible birth defects without CHDs than for infants with isolated Down syndrome. Mean and median numbers of hospitalized days were also significantly greater for infants with Down syndrome and severe or non-severe CHDs or major FBDR-eligible birth defects without CHDs in comparison to infants with isolated Down syndrome.

Table 2.

Hospital resource utilization during infancy among Florida-born infants with Down syndrome, 1998-2007

| Down syndrome case classification |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalization period | All infants | Isolateda | Severe CHDb | Non-severe CHDb | Other major FBDRc-eligible birth defects without CHDb |

| Birth hospitalization | |||||

|

| |||||

| Number of children with admissions during periodd |

2,366e | 746 | 562 | 867 | 191 |

| Mean (SDf) hospitalized daysg,h (days) | 13.4 (23.0) | 6.0 (10.4) | 23.4 (34.0)* | 12.0 (16.0)* | 19.0 (32.0)* |

| Median (IQRf) hospitalized daysg,h (days) | 5 (2-14) | 3 (2-6) | 9 (3-30)* | 6 (3-15)* | 7 (3-21)* |

| Mean (SD) inpatient costh,i ($) | 22,449 (56,884) | 7,578 (24,549) | 48,820 (94,390)* | 16,752 (30,201)* | 29,286 (65,799)* |

| Median (IQR) inpatient costh,i ($) | 5,247 (1,609-18,331) | 1,791 (941-6,010) | 13,425 (3,085-44,658)* | 7,306 (2,373-19,756)* | 7,335 (1,392-30,556)* |

|

| |||||

| Post-birth hospitalization during infancy | |||||

|

| |||||

| Number of children with admissions initiated during period |

1,149 | 160 | 512 | 381 | 96 |

| Median (IQR) Inpatient admissions (n) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-1) | 1 (1-2)* | 1 (1-3)* | 1 (1-1) |

| Mean (SD) hospitalized days (days) | 15.6 (24.0) | 7.1 (12.7) | 22.2 (30.3)* | 10.6 (15.5)* | 14.5 (18.1)* |

| Median (IQR) hospitalized days (days) | 8 (4-17) | 4 (2-7) | 13 (7-23)* | 6 (3-11)* | 8 (3-19)* |

| Mean (SD) inpatient cost ($) | 39,783 (65,939) | 10,114 (23,604) | 68,907 (84,393)* | 17,607 (31,567)* | 21,907 (31,057)* |

| Median (IQR) inpatient cost ($) | 23,272 (5,495-48,404) | 3,896 (2,329-8,273) | 46,365 (31,802-66,997)* | 7,582 (3,837-18,176)* | 11,138 (3,893-25,922)* |

|

| |||||

| Total infancy | |||||

|

| |||||

| Number of children with admissions initiated during period |

2,497 | 767 | 612 | 917 | 201 |

| Median (IQR) Inpatient admissions (n) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-1) | 1 (1-2)* | 1 (1-3)* | 1 (1-2)* |

| Mean (SD) hospitalized days (days) | 20.5 (32.4) | 7.5 (12.5) | 41.9 (48.9)* | 16.0 (19.8)* | 25.2 (34.9)* |

| Median (IQR) hospitalized days (days) | 9 (3-23) | 3 (2-8) | 25 (13-52)* | 9 (4-20)* | 15 (4-29)* |

| Mean (SD) inpatient cost ($) | 41,568 (84,572) | 9,706 (27,569) | 109,059 (134,293)* | 23,645 (39,095)* | 39,421 (70,339)* |

| Median (IQR) inpatient cost ($) | 13,093 (2,939-46,139) | 2,505 (1,171-8,175) | 67,509 (43,187-118,690)* | 11,188 (4,024-28,463)* | 16,765 (4,204-41,182)* |

Notes.

Indicates p < 0.05, comparison group = isolated Down syndrome (Wilcoxon rank-sum test);

Isolated Down syndrome = no other International Classification of Disease, 9th revision; Clinical Modification ( ICD-9-CM) code for any major birth defect;

CHD = congenital heart defect;

FBDR= Florida Birth Defects Registry;

Resource utilization indicators refer to admissions initiated, but not necessarily completed, within the specified period. Not all children are represented in each time point;

Not all children in the FBDR had linked hospital discharge records for each time period of interest, including birth hospitalizations;

SD =standard deviation, IQR =interquartile range;

Hospitalized days refers to the number of days that an infant spent in the hospital for all admissions initiated within the specified period;

Hospitalizations were assessed as continuous episodes of hospital care, regardless of whether a transfer took place. Multiple admission records were merged into one if an infant was admitted to a hospital on the same day as a discharge from a previous admission, or if the infant was admitted to a hospital on the day after a previous discharge with an accompanying “transfer” code;

Presented as 2012 values. Estimated costs calculated as total charges adjusted using statewide year-specific cost-to-charge ratios. Inpatient charges include all hospital facility charges (excludes professional fees): pharmacy, medical and surgical supply, laboratory, radiology and other imaging, cardiology, operating room, anesthesia, recovery room, emergency room (if an inpatient admission originated in the emergency room), treatment or observation room (if a visit resulted in an inpatient admission) charges.

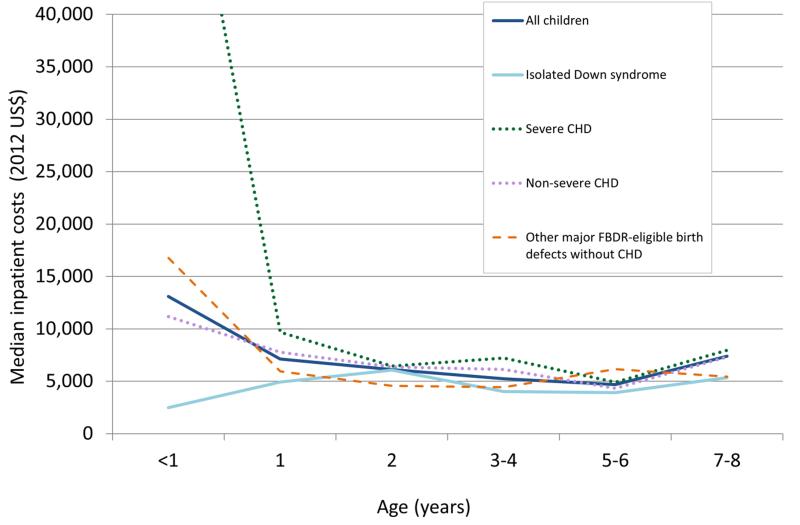

Median estimated inpatient costs for all children with Down syndrome decreased with increasing age until age six and then increased for ages seven to eight (Table 3). However, there were relatively small numbers of children in the older age groups, and most likely co-morbid conditions contributed to the inpatient resource utilization. Children with Down syndrome and severe and non-severe CHDs had significantly greater median inpatient costs for hospitalizations at age one and ages three to four in comparison to children with isolated Down syndrome. Beyond infancy, there were no significant differences in hospital resource utilization for children with Down syndrome and major FBDR-eligible birth defects without CHDs compared to children with isolated Down syndrome. Median inpatient costs were higher for children with Down syndrome and severe CHDs than any other sub-group, particularly during the first two years of life (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Hospital resource utilization during childhood among Florida-born children with Down syndrome, 1998-2007

| Down syndrome case classification |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | All children | Isolateda | Severe CHDb | Non-severe CHDb | Other major birth FBDRc-eligible defects without CHDb |

| 1 | |||||

|

| |||||

| Number (% of total) of children with admissions initiated during periodd |

507 (19.9) | 107 | 145 | 214 | 41 |

| Median (IQRe) inpatient admissions (n) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) |

| Median (IQR) hospitalized daysf,g (days) | 4 (2-9) | 4 (2-7) | 5 (2-13) | 4 (3-9) | 3 (2-7) |

| Median (IQR) inpatient costg,h ($) | 7,128 (3,150-18,526) | 4,924 (2,224-12,025) | 9,680 (4,019-25,481)* | 7,786 (3,581-19,535)* | 5,951 (2,276-9,479) |

|

| |||||

| 2 | |||||

|

| |||||

| Number (% of total) of children with admissions initiated during period |

266 (10.4) | 62 | 74 | 114 | 16 |

| Median (IQR) inpatient admissions (n) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) |

| Median (IQR) hospitalized days (days) | 4 (2-8) | 4 (2-8) | 4 (2-11) | 4 (2-8) | 4 (1-6) |

| Median (IQR) inpatient cost ($) | 6,137 (3,011-15,222) | 6,073 (2,680-13,259) | 6,459 (3,187-25,818) | 6,379 (3,024-16,187) | 4,568 (3,153-7,516) |

|

| |||||

| 3-4 | |||||

|

| |||||

| Number (% of total) of children with admissions initiated during period |

295 (11.6) | 78 | 77 | 113 | 27 |

| Median (IQR) inpatient admissions (n) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-1) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-1) |

| Median (IQR) hospitalized days (days) | 3 (2-6) | 3 (2-4) | 5 (3-8) | 3 (2-7) | 4 (2-15) |

| Median (IQR) inpatient cost ($) | 5,240 (2,836-11,721) | 4,033 (2,291-6,688) | 7,223 (3,175-17,547)* | 6,148 (3,026-12,895)* | 4,432 (3,156-34,988) |

|

| |||||

| 5-6 | |||||

|

| |||||

| Number (% of total) of children with admissions initiated during period |

136 (5.3) | 33 | 46 | 49 | 8 |

| Median (IQR) inpatient admissions (n) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-1) | 1 (1-1) | 1 (1-1) |

| Median (IQR) hospitalized days (days) | 3 (2-6) | 3 (2-6) | 3 (2-6) | 3 (2-5) | 4 (3-8) |

| Median (IQR) inpatient cost ($) | 4,706 (2,572-10,562) | 3,937 (2,112-7,563) | 4,914 (2,957-11,296) | 4,342 (2,556-11,831) | 6,173 (3,893-19,576) |

|

| |||||

| 7-8 | |||||

|

| |||||

| Number (% of total) of children with admissions initiated during period |

68 (2.7) | 23 | 19 | 22 | 4 |

| Median (IQR) inpatient admissions (n) | 1 (1-1) | 1 (1-1) | 1 (1-1) | 1 (1-2) | 1 (1-1) |

| Median (IQR) hospitalized days (days) | 3 (2-9) | 3 (1-7) | 5 (2-10) | 4 (2-10) | 2 (1-4) |

| Median (IQR) inpatient cost ($) | 7,411 (2,915-15,260) | 5,359 (2,547-17,460) | 7,956 (4,221-7,956) | 7,343 (3,418-10,073) | 5,444 (2,152-9,397) |

Notes.

Indicates p <0.05, comparison group = isolated Down syndrome (Wilcoxon rank-sum test);

Isolated Down syndrome = no other International Classification of Disease, 9th revision; Clinical Modification ( ICD-9-CM) code for any major birth defect;

CHD = congenital heart defect;

FBDR= Florida Birth Defects Registry;

Resource utilization indicators refer to admissions initiated, but not necessarily completed, within the specified period. Not all children are represented in each time point;

SD =standard deviation, IQR =interquartile range;

Hospitalized days refers to the number of days that an infant spent in the hospital for all admissions initiated within the specified period;

Hospitalizations were assessed as continuous episodes of hospital care, regardless of whether a transfer took place. Multiple admission records were merged into one if an infant was admitted to a hospital on the same day as a discharge from a previous admission, or if the infant was admitted to a hospital on the day after a previous discharge with an accompanying “transfer” code.;

Presented as 2012 values. Estimated costs calculated as total charges adjusted using statewide year-specific cost-to-charge ratios. Inpatient charges include all hospital facility charges (excludes professional fees): pharmacy, medical and surgical supply, laboratory, radiology and other imaging, cardiology, operating room, anesthesia, recovery room, emergency room (if an inpatient admission originated in the emergency room), treatment or observation room (if a visit resulted in an inpatient admission) charges.

Figure 1.

Trends in estimated inpatient costs for children with Down syndrome in Florida, 1998-2007. Isolated Down syndrome was defined as no other International Classification of Disease, 9th revision; Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code for any major birth defect included in the Florida Birth Defects Registry (FBDR). CHD=congenital heart defect.

DISCUSSION

This analysis described the demographics and hospital resource utilization for 2,552 Florida-born children with Down syndrome. The mortality rate during the study period was significantly greater for children with Down syndrome and severe CHDs and major FBDR-eligible birth defects without CHDs and significantly lower for children with Down syndrome and non-severe CHDs than for children with isolated Down syndrome. Estimated inpatient costs and number of hospitalized days were significantly greater for children with Down syndrome and severe CHDs (with or without other major FBDR-eligible birth defects) and for children with Down syndrome and major FBDR-eligible birth defects without CHDs than for children with Down syndrome and non-severe CHDs or isolated Down syndrome during the first year of life. Infants with severe CHDs and major FBDR-eligible birth defects without CHDs were also significantly more likely to be born low birth weight than infants with isolated Down syndrome, which likely contributed to the difference in hospital resource utilization observed during infancy. During early childhood, inpatient costs were significantly greater for children with Down syndrome and severe or non-severe CHDs than for children with isolated Down syndrome, but this difference became less pronounced with increasing age.

Although our study utilized data from a single state, our findings about the importance of other birth defects in patterns of hospital use by children with Down syndrome were generally consistent with other studies. For example, a longitudinal study of linked birth defects surveillance and hospital discharge records in Massachusetts for children with Down syndrome found that during the first three years of life, total hospital days were almost twice as great for those with either CHDs or a non-cardiac major birth defect compared to children with Down syndrome without CHDs or non-cardiac birth defects (Derrington et al., 2013). In a 2013 study of hospitalizations among children and adults with and without Down syndrome, using data from the Danish health care system, researchers found that presence of other malformations, especially CHDs, was an important predictor of the relative frequency of hospital days (Zhu et al., 2013). That study examined data for all age ranges of individuals with Down syndrome and found that relative hospital use was greatest among children under the age of five years.

A study of school-aged children with Down syndrome in Western Australia observed a decrease in healthcare utilization for children with Down syndrome and CHDs and less ongoing cardiac co-morbidity in a 2004 survey compared to a 1997 survey (Thomas et al., 2011). The authors hypothesized that this difference was due to improvements in early identification and surgical repair of CHDs, which is supported by our findings that the majority of hospital resource utilization for children with Down syndrome and CHDs occurred in early childhood. Researchers in a second study, using data from Western Australia, found that the majority of health costs for children with Down syndrome occurred during the first two years of life and declined with increasing age (Geelhoed et al., 2011), which is consistent with our findings.

Using data from the 2004 MarketScan Commercial Database, researchers reported that infants with Down syndrome averaged 49 days in the hospital during the first year of life and had mean inpatient cost of $87,568 in 2012 dollars (Boulet et al., 2008). Both estimates are more than twice as large as our study’s findings of 20 hospital days and $41,568 mean inpatient costs. Our estimates of median inpatient costs beyond infancy, however, appear consistent with the estimates of mean costs in the MarketScan study.

Our findings on number of hospitalized days during infancy are consistent with a previous analysis from Massachusetts for 1999-2004 (Derrington et al., 2013). We found that beyond infancy median inpatient costs for children with Down syndrome did not differ markedly or consistently between those with and without other birth defects, cardiac or non-cardiac. Costs were higher for one-year-olds with severe CHDs. The differences in costs between children with Down syndrome and severe and mild CHDs after infancy are quite modest compared with cost differences for all children with Down syndrome and CHDs (Boulet et al., 2009), which could reflect differences in the spectrum of CHDs in children with Down syndrome.

There were several limitations for this project. The FBDR is a passive birth defects surveillance system, which identified infants with Down syndrome based on ICD-9-CM codes and did not include verbatim or clinically-verified diagnoses for Down syndrome or other birth defects, including CHDs (Strickland et al., 2008). We may have under-ascertainment of children with Down syndrome that were diagnosed after infancy; an estimated 87% of live-born infants with Down syndrome are diagnosed postnatally and the timing of postnatal diagnosis varies widely, although the majority of these infants are diagnosed at birth (Skotko, 2005; de Groot-van der Mooren et al., 2014). Because the study cohort included only children with birth defects, we were unable to compare our results with hospital resource utilization for children without birth defects. However, our data did allow for comparison of hospital resource utilization among children with isolated Down syndrome in comparison to those with Down syndrome and CHDs or other major FBDR-eligible birth defects. Another limitation was that the principal healthcare payer was the expected payer and may not have been the actual payer. In addition, there may be instances where two payers shared the cost of the hospitalization. We were unable to examine the effect to which these limitations may have influenced our results. We were also limited by our lack of information on the prenatal experience, including prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome or other birth defects. An examination of maternal demographics indicated a higher proportion of Hispanic and foreign-born mothers among mothers of children with Down syndrome and CHDs than mothers of children with isolated Down syndrome, suggesting differential access to or use of prenatal care, antenatal diagnosis, or ascertainment (Kucik et al., 2012).

This study was also limited by the use of a statewide cost-to-charge ratio to convert inpatient charges to costs. This cost conversion method is most accurate when there is low variability in cost mark-up between hospitals and departments within a hospital (Rogowski, 1999). Therefore, use of statewide cost-to-charge ratios may be problematic due to potentially wide variability in the difference between costs and charges by hospital and within hospital departments (Salemi et al., 2013b). Additionally, cost-to-charge ratios were unavailable for years prior to 2001, resulting in use of the 2001 ratio to impute the missing cost-to-charge ratios for 1998-2000. As cost-to-charge ratios have decreased over time, costs for hospitalizations during 1998-2000 are a slight underestimate. We also did not have information on professional fees as hospital discharge data only included facility fees. Based on an analysis of claims data from California, it was estimated that hospitalization costs per child could be underestimated by about one-fifth in the present analysis (Rogowski, 1998). In addition, some post-birth hospital visits may have occurred outside Florida and were not included in our analysis. The FBDR does not include linked maternal labor and delivery records, therefore, some birth hospitalization use and costs might have been applied to the mothers’ records.

This study had several strengths. The FBDR is a statewide, population-based registry and includes multiple sources of birth defects ascertainment. This study included a unique combination of registry data linked to longitudinal hospital data. Florida has a racially and ethnically diverse source population with a large number of annual births (Hamilton et al., 2011). This analysis highlights the linkage between birth defects surveillance data and available hospital discharge records, which may be a cost-efficient approach to assessing resource utilization beyond infancy.

CONCLUSION

Results support findings that for children with Down syndrome the presence of other anomalies influences hospital use and costs, and children with Down syndrome and severe CHDs have greater hospital resource utilization than children with Down syndrome and other CHD types. Further examination of the impact of parent/household and child characteristics on hospital resource utilization is warranted. Our findings suggest that birth defects registry and hospital discharge data can provide useful tools for evaluating patterns of hospital use and associated costs over time.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the staff of the Florida Department of Health’s FBDR, Children’s Medical Services Program, and Florida AHCA for data accessibility and acquisition. We also thank Adrienne Henderson and Gloria Barker with the Florida AHCA, Florida Center for Health Information and Policy Analysis and Karen Freeman with the Florida Department of Health for consultations on hospital discharge data and Florida hospitals. We thank Jason L. Salemi at the University of South Florida and Marie Bailey at the Florida Department of Health for consultations on data linkages and variables. Lastly, we acknowledge the March of Dimes Foundation for providing funding for this project (Research Grant No. #5-FY09-533).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Parts of this manuscript were presented at the following meetings: Connecting What Counts: Surveillance, Services, and Supports for Children with Down Syndrome Conference, Oct 11-12, 2012, Tampa, FL; Maternal Child Health/Epidemiology Conference, San Antonio, TX, Dec 12-14, 2012; National Birth Defects Prevention Network Annual Meeting, Atlanta, GA, Feb 25-27, 2013; and Pediatric Research Retreat: Common Complex Childhood Diseases, Atlanta, GA, June 28, 2013.

Disclaimer:The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- Agency for Health Care Administration [Accessed September 19, 2012];Florida Agency for Health Care Administration. http://ahca.myflorida.com/

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Health Care Utilization Project [Accessed June 26, 2013];Cost-to-charge ratio files: 2010 central distributor State Inpatient Database. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/state/costtocharge.jsp.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn Levels of neonatal care. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):1341–1347. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baraona F, Gurvitz M, Landzberg MJ, Opotowsky AR. Hospitalizations and mortality in the United States for adults with Down syndrome and congenital heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111(7):1046–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulet SL, Grosse SD, Correa-Villasenor A, Riehle-Colarusso T. Heath care costs of congenital heart defects. In: Wyszynski DF, Graham T, Correa-Villasenor A, editors. Congenital heart defects: from origin to treatment. Oxford University Press; New York: 2009. pp. 493–501. [Google Scholar]

- Boulet SL, Molinari NA, Grosse SD, Honein MA, Correa-Villasenor A. Health care expenditures for infants and young children with Down syndrome in a privately insured population. J Pediatr. 2008;153(2):241–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Hospital stays, hospital charges, and in-hospital deaths among infants with selected birth defects--United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(2):25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colvin L, Bower C. A retrospective population-based study of childhood hospital admissions with record linkage to a birth defects registry. BMC Pediatrics. 2009;9:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-9-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor JA, Gauvreau K, Jenkins KJ. Factors associated with increased resource utilization for congenital heart disease. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):689–695. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groot-van der Mooren MD, Gemke RJ, B J, Cornel MC, Weijerman ME. Neonatal diagnosis of Down syndrome in the Netherlands: suspicion and communication with parents. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jir.12125. doi: 10.1111/jir.12125. Epub 2014 Mar 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrington TM, Kotelchuck M, Plummer K, Cabral H, Lin AE, Belanoff C, Shin M, Correa A, Grosse SD. Racial/ethnic differences in hospital use and cost among a statewide population of children with Down syndrome. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2013;34(10):3276–3287. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2013.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florida Department of Health [Accessed September 19, 2012];Florida Birth Defects Registry. Report on birth defects in Florida: 1998-2007. http://www.fbdr.org/pdf/FBDR_report_May2011.pdf.

- Freeman SB, Taft LF, Dooley KJ, Allran K, Sherman SL, Hassold TJ, Khoury MJ, Saker DM. Population-based study of congenital heart defects in Down syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1998;80(3):213–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geelhoed EA, Bebbington A, Bower C, Deshpande A, Leonard H. Direct health care costs of children and adolescents with Down syndrome. J Pediatr. 2011;159(4):541–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2. Vol. 60. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2011. Births: Preliminary Data for 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Harris JA, James L. State-by-state cost of birth defects--1992. Teratology. 1997;56(1-2):11–16. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199707/08)56:1/2<11::AID-TERA4>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ireys HT, Anderson GF, Shaffer TJ, Neff JM. Expenditures for care of children with chronic illnesses enrolled in the Washington State Medicaid program, fiscal year 1993. Pediatrics. 1997;100(2 Pt 1):197–204. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucik JE, Alverson CJ, Gilboa SM, Correa A. Racial/ethnic variations in the prevalence of selected major birth defects, metropolitan Atlanta, 1994-2005. Public Health Rep. 2012;127(1):52–61. doi: 10.1177/003335491212700106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahle WT, Newburger JW, Matherne GP, Smith FC, Hoke TR, Koppel R, Gidding SS, Beekman RH, Grosse SD. Role of pulse oximetry in examining newborns for congenital heart disease: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and American Academy of Pediatrics. Circulation. 2009;120:447–458. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Birth Defects Prevention Network State birth defects surveillance program directory. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2011;91:1028–1149. [Google Scholar]

- Neff JM, Sharp VL, Muldoon J, Graham J, Myers K. Profile of medical charges for children by health status group and severity level in a Washington State Health Plan. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(1):73–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00216.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SE, Mai CT, Canfield MA, Rickard R, Wang Y, Meyer RE, Anderson P, Mason CA, Collins JS, Kirby RS, Correa A, National Birth Defects Prevention Network Updated national birth prevalence estimates for selected birth defects in the United States, 2004-2006. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2010;88(12):1008–1016. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogowski J. Cost-effectiveness of care for very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 1998;102:35–43. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogowski J. Measuring the cost of neonatal and perinatal care. Pediatrics. 1999;103(1 Suppl E):329–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo CA, Elixhauser A. HCUP Statistical brief #24. U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: 2007. Hospitalizations for birth defects, 2004. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb24.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salemi JL, Hauser KW, Tanner JP, Sampat D, Correia JA, Watkins SM, Kirby RS. Developing a database management system to support birth defects surveillance in Florida. J Registry Manag. 2010;37(1):10–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salemi JL, Tanner JP, Bailey M, Mbah AK, Salihu HM. Creation and evaluation of a multi-layered maternal and child health database for comparative effectiveness research. J Registry Manag. 2013;40(1):14–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salemi JL, Comins MM, Chandler K, Mogos MF, Salihu HM. A practical approach for calculating reliable cost estimates from observational data: application to cost analyses in maternal and child health. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy. 2013;11(4):343–357. doi: 10.1007/s40258-013-0040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salemi JL, Tanner JP, Block S, Bailey M, Correia JA, Watkins SM, Kirby RS. The relative contribution of data sources to a birth defects registry utilizing passive multisource ascertainment methods: does a smaller birth defects case ascertainment net lead to overall or disproportionate loss? J Registry Manag. 2011;38(1):30–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skotko BG. Prenatally diagnosed Down syndrome: mothers who continued their pregnancies evaluate their health care providers. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(3):670–677. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland MJ, Riehle-Colarusso TJ, Jacobs JP, Reller MD, Mahle WT, Botto LD, Tolbert PE, Jacobs ML, Lacour-Gayet FG, Tchervenkov CI, Mavroudis C, Correa A. The importance of nomenclature for congenital cardiac disease: implications for research and evaluation. Cardiology in the Young. 2008;18(Suppl 2):92–100. doi: 10.1017/S1047951108002515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas K, Bourke J, Girdler S, Bebbington A, Jacoby P, Leonard H. Variation over time in medical conditions and health service utilization of children with Down syndrome. J Pediatr. 2011;158(2):194–200. e191. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics [Accessed April 30, 2013];Producer price index industry data: hospitals. Series PCU622. http://www.bls.gov/ppi.

- Waitzman NJ, Scheffler RM, Romano PS. The cost of birth defects: estimates of the value of prevention. University Press of America; Lanham, MD: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JL, Hasle H, Correa A, Schendel D, Friedman JM, Olsen J, Rasmussen SA. Hospitalizations among people with Down syndrome: a nationwide population-based study in Denmark. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2013;161(4):650–657. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]