Abstract

Objectives

Critical congenital heart disease (CCHD) was added recently to the U.S. Recommended Uniform Screening Panel for newborns. This study assessed whether maternal/household and infant characteristics were associated with late CCHD detection.

Methods

This was a state-wide, population-based, retrospective, observational study of infants with CCHD born 1998-2007 identified by the Florida Birth Defects Registry. We examined 12 CCHD conditions that are primary and secondary targets of newborn CCHD screening by pulse oximetry. We used Poisson regression models to analyze associations between selected characteristics (e.g., maternal age, CCHD type, and birth hospital nursery level [highest level available in the hospital]) and late CCHD detection, which was defined as diagnosis after the birth hospitalization.

Results

Of 3,603 infants with CCHD and linked hospitalizations, CCHD was not detected during the birth hospitalization for 22.9% (n=825) of infants. The likelihood of late detection varied by CCHD condition. Infants born in a birth hospital with a Level I nursery only (adjusted prevalence ratio [aPR] 1.9, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.6-2.2) or Level II nursery (aPR 1.5, 95% CI 1.3-1.7) were significantly more likely to have late-detected CCHD compared to infants born in a birth hospital with a Level III (highest) nursery.

Conclusions

After controlling for the selected characteristics, hospital nursery level appears to have an independent association with late CCHD detection. Thus, perhaps universal newborn screening for CCHD could be particularly beneficial in Levels I and II nurseries and may reduce differences in the frequency of late diagnosis between birth hospital facilities.

Keywords: congenital heart disease, neonatal screening

INTRODUCTION

Infants with critical congenital heart disease (CCHD) – heart defects requiring surgical or catheter intervention in the first year of life – are at risk for cardiovascular collapse or death if discharged from the birth hospital without a CCHD diagnosis.1 Pulse oximetry monitoring is the instrument currently used for CCHD screening. It is a non-invasive measurement of blood oxygen saturation that, in some cases, can detect CCHD in newborns whose condition was not detected prenatally or during routine postnatal examination.2 In light of recent clinical evidence of the benefits of pulse oximetry screening, CCHD was added to the U.S. Recommended Uniform Screening Panel for newborns in 2011.3

Few studies have investigated factors associated with late or missed detection of critical or other congenital heart disease (CHD). In a 1999 study using data from the Baltimore-Washington Infant Study (BWIS), researchers found that among infants with CHD who died during the first year of life, factors associated with missed CHD diagnosis included the presence of multiple congenital malformations, low birth weight, prematurity, intrauterine growth restriction, and CHD type.4 The authors also found an association between missed diagnosis and low paternal education, but did not find a correlation with other paternal or maternal sociodemographic characteristics.4 In a study using California state-wide death registry data between 1998-2004, researchers estimated that 0.9 per 100,000 infants in California, extrapolated to approximately 36 infants in the United States, die annually due to missed CCHD diagnosis and the likelihood of death due to missed diagnosis varied by CCHD type.5

In a 2013 study using data from the Florida Birth Defects Registry (FBDR), researchers found 22.9% of infants born 1998-2007 and ultimately diagnosed with CCHD did not receive a CCHD diagnosis during their birth hospitalization.6 Our objective was to use these same population-based data to examine whether selected characteristics were associated with late CCHD detection. In particular, we examined hospital nursery level of care because research suggests that tertiary level hospitals may detect fewer additional infants with CCHD through screening because of greater clinical awareness and use of prenatal diagnosis relative to community hospitals.7

METHODS

Study population

This was a state-wide, population-based, retrospective, observational study of infants with CCHD born January 1, 1998, through December 31, 2007, identified by the FBDR. The FBDR is a passive, state-wide, population-based surveillance system that identifies infants with birth defects, such as CCHD, from multiple databases of health care information.8-10 Infants in the FBDR are ascertained during the first year of life, primarily using hospital discharge records from Florida’s Agency for Health Care Administration (AHCA).8-11 AHCA does not collect information from non-hospital based birthing centers, though approximately 99% of births in Florida are in-hospital.12 The FBDR also includes information from state vital statistics, thereby capturing infant deaths that occur outside of the hospital setting. The FBDR does not capture information on adopted infants, prospective adoptees or on infants whose mothers delivered out-of-state.8-10,13

There were several inclusion criteria for this analysis. First, infants had an International Classification of Disease, 9th revision; Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code in the FBDR for CCHD conditions considered as primary or secondary targets of newborn pulse oximetry screening. Primary targets include defects that always or most always present with hypoxemia: dextro-transposition of the great arteries [d-TGA], 745.10; truncus arteriosus [TA], 745.0; total anomalous pulmonary venous connection [TAPVC], 747.41; tricuspid atresia [TRA], 746.1; pulmonary atresia (with intact septum) [PA], 746.01; hypoplastic left heart syndrome [HLHS], 746.7; tetralogy of Fallot [TOF], 745.2.1,14,15 Secondary targets include defects that sometimes present with hypoxemia: double-outlet right ventricle [DORV], 745.11; Ebstein anomaly [EA], 746.2; coarctation/hypoplasia of aortic arch [COA], 747.10; aortic interruption/atresia/hypoplasia [AI/A], 747.11, 747.22; and single ventricle [SV], 745.3.1,14,15 Secondly, infants had a corresponding birth hospitalization discharge record from AHCA. Lastly, if there was no CCHD ICD-9-CM code on the birth hospitalization record, infants had at least one subsequent hospital admission or record of death due to any cause within the first year of life.

Variable construction

Our outcome of interest was late detection of CCHD compared to timely detection. Timely detection was defined as the presence of any CCHD ICD-9-CM diagnosis code on the birth hospital discharge record or, if applicable, on a subsequent hospitalization determined to be a transfer from the birth hospital. Hospitalizations were considered transfers if the subsequent admission occurred on the same day as the birth hospital discharge or within one day of birth hospital discharge and an accompanying “transfer” admission code was present.

Selected maternal/household characteristics of interest were: age, race/ethnicity, nativity, education, expected principal healthcare payer status during the birth hospitalization, and birth hospital nursery level (I, III, or III [highest]).15 Principal healthcare payer status was defined as private insurance (i.e., employer-based insurance, including Tricare), public insurance (i.e., Medicare, Medicaid, Veteran’s Administration insurance, or other state/local government insurance in Florida), and self-pay/uninsured. The birth hospital nursery level was coded as the highest level in the facility (e.g., a hospital with Level II and III beds was classified as Level III). Infant characteristics of interest were: sex, preterm birth, presence of a non-cardiac congenital anomaly (i.e., major structural defects and selected genetic conditions), plurality, and specific CCHD condition.

Statistical analysis

Because late detection of CCHD was relatively common in our study population (i.e., 23% prevalence), we estimated the relative risk of late detection related to each characteristic of interest by comparing the prevalence of late detection at each exposure level. For each variable of interest, which was selected a priori, we estimated unadjusted and adjusted prevalence ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals in Poisson regression models with robust variance estimation.17

For multivariable analysis, we constructed two primary models: 1) effect of CCHD type for infants with a single CCHD condition, excluding infants with multiple CCHDs; and 2) effect of single CCHD versus multiple CCHDs among the entire study sample. All other variables of interest were included in both models. Although our main analyses included both primary and secondary CCHD screening targets, we also report separate analyses restricted to infants with the primary screening targets (i.e., d-TGA, TA, TAPVC, TRA, PA, HLHS, TOF).1,14,15 Finally, we conducted a separate analysis restricted to infants that did not experience a birth hospital transfer because infants who were transferred from their birth hospital may be different in terms of symptoms or severity than non-transferred infants. All models controlled for infants’ birth year with time dummy variables. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

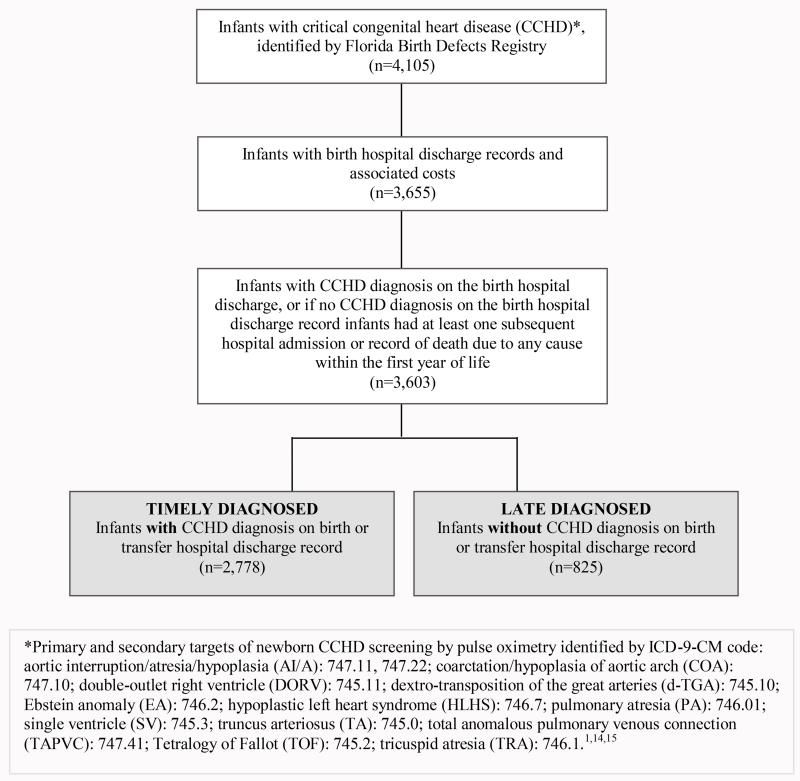

We identified 4,105 infants with ICD-9-CM codes indicating a CCHD in the FBDR and born 1998 - 2007, with an estimated birth prevalence of 19 per 10,000 live births (n=4,105/2,135,000).13 Among these infants, 3,655 had a birth hospitalization discharge record. Of these infants, 3,603 had a CCHD diagnosis on the birth hospitalization discharge record or at least one subsequent hospital discharge record or record of death and constituted the group of infants for analysis (Figure 1). Infants with CCHD in the FBDR that did not meet any of the inclusion criteria (n=502, 12.2%) were significantly more likely to have been born to mothers who were less educated, unmarried, foreign-born, and of Hispanic ethnicity than infants included in the analysis. Infants excluded from the analysis were more likely to be multiple births than infants included in the analysis. There were no significant differences in maternal age, infant sex, birth year, or death during infancy between infants included and excluded from the analysis.

Figure 1.

Infant data inclusion flowchart

Among the 3,603 infants, 22.9% (n=825) of infants had late-detected CCHD (Table 1). Among infants with one of the seven primary CCHD screening targets (n=1,639, 45.5%), 21.2% (n=348) had late-detected CCHD. The most common single CCHD condition among infants with timely detection was TOF (20.2%; n=561/2,778). The most common condition among infants with late-detected CCHD was COA (33.3%; n=275/825). Approximately 20% (n=568/2,778) of timely-detected infants and 8.0% (n=66/825) of late-detected infants died during infancy. About 53% (n=1,462/2,778) of timely-detected infants and 10.3% (n=85/825) of late-detected infants were transferred to another hospital during the birth hospitalization.

Table 1.

Selected characteristics of Florida-born infants with critical congenital heart disease (CCHD) (n=3,603), 1998-2007

| Characteristic | Infants with timely detected CCHD (n=2,778) n (%) |

Infants with late detected CCHD (n=825) n (%) |

Unadjusted prevalence ratio (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal / household | |||

|

| |||

| Mother’s age, years | |||

| ≤ 24 | 945 (34.0) | 321 (38.9) | 1.2 (1.0-1.3) |

| 25-34 | 1,338 (48.2) | 376 (45.6) | Reference |

| ≥ 35 | 495 (17.8) | 128 (15.5) | 0.8 (0.7-1.0) |

| Mother’s race / ethnicity | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 1,495 (53.9) | 470 (57.0) | Reference |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 621 (22.4) | 178 (21.6) | 1.0 (0.8-1.1) |

| Hispanic | 586 (21.1) | 155 (18.8) | 0.9 (0.8-1.1) |

| Asian / Pacific Islander and American Indian / Alaskan |

50 (1.8) | 17 (2.1) | 1.0 (0.6-1.5) |

| Mother’s education | |||

| Less than high school graduate | 564 (20.3) | 177 (21.5) | 1.1 (0.9-1.3) |

| High school graduate or equivalent | 912 (32.8) | 304 (36.9) | 1.2 (1.1-1.4) |

| College or university (some or graduate) | 1,275 (45.9) | 340 (41.2) | Reference |

| Mother’s nativity: foreign-born | 677 (24.4) | 163 (19.8) | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) |

| Principal healthcare payer type on birth hospitalization recorda | |||

| Private | 1,324 (47.7) | 377 (45.7) | Reference |

| Public | 1,360 (49.0) | 409 (49.6) | 1.1 (0.9-1.2) |

| Self-Insured/Uninsured | 94 (3.4) | 39 (4.7) | 1.3 (0.9-1.7) |

| Birth hospital nursery level | |||

| I | 425 (15.3) | 250 (30.3) | 2.1 (1.8-2.4) |

| II | 598 (21.5) | 214 (25.9) | 1.5 (1.3-1.8) |

| III | 1,755 (63.2) | 361 (43.8) | Reference |

|

| |||

| Infant | |||

|

| |||

| Sex, female | 1,195 (43.0) | 361 (43.8) | 1.0 (0.9-1.2) |

| Preterm or very preterm birth (20-36 weeks) | 595 (21.4) | 143 (17.3) | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) |

| Non-cardiac congenital anomaly | 883 (31.8) | 250 (30.3) | 0.9 (0.8-1.1) |

| Plurality, multiple gestation | 54 (1.9) | 9 (1.1) | 0.7 (0.4-1.3) |

| Critical congenital heart disease (CCHD) typeb,c | |||

| Single condition | |||

| Hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS)c | 196 (7.1) | 27 (3.3) | Reference |

| Aortic interruption/atresia/hypoplasia (AI/A) | 70 (2.5) | 26 (3.2) | 2.2 (1.4-3.6) |

| Coarctation/hypoplasia of aortic arch (COA) | 472 (17.0) | 275 (33.3) | 3.0 (2.1-4.4) |

| Double-outlet right ventricle (DORV) | 77 (2.8) | 32 (3.9) | 2.4 (1.5-3.8) |

| Dextro-transposition of the great arteries (d-TGA)c | 234 (8.4) | 26 (3.2) | 0.8 (0.5-1.4) |

| Ebstein anomaly (EA) | 76 (2.7) | 11 (1.3) | 1.0 (0.5-2.0) |

| Pulmonary atresia (PA)c | 74 (2.7) | 22 (2.7) | 1.9 (1.1-3.2) |

| Single ventricle (SV) | 24 (0.9) | 8 (1.0) | 2.1 (1.0-4.1) |

| Truncus arteriosus (TA)c | 69 (2.5) | 32 (3.9) | 2.6 (1.7-4.1) |

| Total anomalous pulmonary venous connection (TAPVC)c |

55 (2.0) | 37 (4.5) | 3.3 (2.2-5.1) |

| Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF)c | 561 (20.2) | 184 (22.3) | 2.0 (1.4-3.0) |

| Tricuspid atresia (TRA)c | 102 (3.7) | 20 (2.4) | 1.4 (0.8-2.3) |

| Multiple conditions | 768 (27.7) | 125 (15.2) | 0.5 (0.4-0.7) |

| Year of birth | |||

| 1998 | 247 (8.9) | 73 (8.9) | 1.1 (0.8-1.5) |

| 1999 | 234 (8.4) | 86 (10.4) | 1.3 (0.9-1.7) |

| 2000 | 268 (9.7) | 77 (9.3) | 1.2 (0.9-1.6) |

| 2001 | 238 (8.6) | 90 (10.9) | 1.4 (1.1-1.9) |

| 2002 | 265 (9.5) | 73 (8.9) | 1.0 (0.8-1.4) |

| 2003 | 276 (9.9) | 77 (9.3) | 1.2 (0.9-1.6) |

| 2004 | 264 (9.5) | 106 (12.9) | 1.4 (1.1-1.9) |

| 2005 | 331 (11.9) | 69 (8.4) | 0.9 (0.6-1.2) |

| 2006 | 322 (11.6) | 82 (9.9) | 0.9 (0.7-1.2) |

| 2007 | 333 (12.0) | 79 (9.6) | Reference |

Bold results indicate p-value <0.05

Private insurance included employer-based insurance (including Tricare). Public insurance included Medicare, Medicaid, Veteran’s Administration insurance, and other state and local government health insurance in Florida, such as KidCare.

CCHD identified by ICD-9-CM codes: HLHS: 746.7, AI/A: 747.11, 747.22; COA: 747.10; DORV: 745.11; d-TGA: 745.10; EA: 746.2; PA: 746.01; SV: 745.3; TA: 745.0; TAPVC: 747.41; TOF: 745.2; TRA: 746.1.

In bivariate analyses, several characteristics were associated with late detection (Table 1). In comparison to mothers 25-34 years of age, infants born to younger mothers (≤ 24 years of age) were significantly more likely to be late-detected. Infants born to mothers with a high school education were more likely to be late-detected than infants whose mother attended college or university. The relative risk of late detection was greater among infants with U.S.-born mothers than among those with foreign-born mothers. Premature infants were less likely than term infants to have late-detected CCHD.

In the multivariable model controlling for CCHD condition among infants with a single CCHD condition, among other factors, the birth hospital nursery level and infants’ CCHD condition were significantly associated with late detection (Table 2). The prevalence of late detection was significantly higher for birth years 2001 and 2004 than 2007. The relative risk of late detection was significantly greater among infants born in a Level I hospital nursery (adjusted prevalence ratio [aPR]: 1.9, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.6-2.2) or Level II hospital nursery (aPR: 1.5, 95% CI: 1.3-1.7) compared to infants born in a birth hospital with a Level III nursery. The magnitude and direction of these associations did not differ substantially in the model controlling for single versus multiple CCHD conditions (Level I nursery aPR: 2.1, 95% CI: 1.8-2.4; Level II nursery aPR: 1.5, 95% CI: 1.3-1.7). The results were similar when the analysis was restricted to infants with one of the primary CCHD screening targets (Level I nursery aPR: 1.9, 95% CI: 1.6-2.4; Level II nursery aPR: 1.3, 95% CI: 1.1-1.7) or when restricted to infants who did not experience birth hospital transfers (Level I nursery aPR: 2.3, 95% CI: 1.9-2.7; Level II nursery aPR: 1.8, 95% CI: 1.5-2.1).

Table 2.

Factors associated with late detection of critical congenital heart disease (CCHD) among Florida-born infants, 1998-2007

| Characteristic | Adjusted prevalence ratioa (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|

| Maternal / household | |

|

| |

| Mother’s age, years | |

| ≤ 24 | 1.0 (0.9-1.2) |

| 25-34 | Reference |

| ≥35 | 1.0 (0.9-1.0) |

| Mother’s race / ethnicity | |

| White, non-Hispanic | Reference |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 1.1 (0.9-1.2) |

| Hispanic | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) |

| Asian / Pacific Islander and American Indian / Alaskan | 1.3 (0.8-2.0) |

| Mother’s education | |

| Less than high school graduate | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) |

| High school graduate or equivalent | 1.2 (1.0-1.4) |

| College or university (some or graduate) | Reference |

| Mother’s nativity: foreign-born | 0.8 (0.7-1.0) |

| Principal healthcare payer type on birth hospitalization recordb | |

| Private | Reference |

| Public | 1.0 (0.9-1.2) |

| Self-Insured/Uninsured | 1.2 (0.9-1.6) |

| Birth hospital nursery level | |

| I | 1.9 (1.6-2.2) |

| II | 1.5 (1.3-1.7) |

| III | Reference |

|

| |

| Infant | |

|

| |

| Sex, female | 1.0 (0.9-1.1) |

| Preterm or very preterm birth (20-36 weeks) | 0.9 (0.7-1.0) |

| Non-cardiac congenital anomaly | 0.9 (0.8-1.1) |

| Plurality: multiple gestation | 0.8 (0.5-1.3) |

| Critical congenital heart disease type (CCHD)c,d | |

| Single condition | |

| Hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS)d | Reference |

| Aortic interruption/atresia/hypoplasia (AI/A) | 2.2 (1.4-3.4) |

| Coarctation/hypoplasia of aortic arch (COA) | 2.9 (2.1-4.0) |

| Double-outlet right ventricle (DORV) | 2.5 (1.7-3.8) |

| Dextro-transposition of the great arteries (d-TGA)d | 0.8 (0.5-1.2) |

| Ebstein anomaly (EA) | 0.8 (0.6-1.7) |

| Pulmonary atresia (PA)d | 1.7 (1.1-2.7) |

| Single ventricle (SV) | 2.2 (1.1-4.1) |

| Truncus arteriosus (TA)d | 2.5 (1.7-3.8) |

| Total anomalous pulmonary venous connection (TAPVC)d | 2.7 (1.8-4.0) |

| Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF)d | 1.9 (1.4-2.6) |

| Tricuspid atresia (TRA)d | 1.3 (0.8-2.1) |

| Year of birth | |

| 1998 | 1.0 (0.8-1.4) |

| 1999 | 1.2 (0.9-1.6) |

| 2000 | 1.2 (1.0-1.6) |

| 2001 | 1.4 (1.1-1.8) |

| 2002 | 1.1 (0.8-1.4) |

| 2003 | 1.2 (0.9-1.5) |

| 2004 | 1.4 (1.1-1.8) |

| 2005 | 0.9 (0.7-1.2) |

| 2006 | 0.9 (0.7-1.1) |

| 2007 | Reference |

Bold results indicate p-value <0.05

Adjusted models controlled for all characteristics listed in the table. The results shown here are for the multivariable model which examined the effect of CCHD type for infants with a single CCHD, and therefore excludes infants with multiple CCHDs.

Private insurance included employer-based insurance (including Tricare). Public insurance included Medicare, Medicaid, Veteran’s Administration insurance, and other state and local government insurance in Florida, such as KidCare.

CCHD identified by ICD-9-CM codes: HLHS: 746.7, AI/A: 747.11, 747.22; COA: 747.10; DORV: 745.11; d-TGA: 745.10; EA: 746.2; PA: 746.01; SV: 745.3; TA: 745.0; TAPVC: 747.41; TOF: 745.2; TRA: 746.1.

Infants with AI/A, COA, DORV, PA, SV, TA, TAPVC, and TOF were significantly more likely to experience late detection compared to infants with HLHS (Table 2). Infants with multiple CCHD conditions were significantly less likely to be late-detected than infants with a single CCHD (aPR: 0.5, 95% CI: 0.4-0.6). In a model restricted to infants with the primary CCHD screening targets, the significance, direction, and magnitude of the association of PA, TA, TAPVR, and TOF and late detection remained similar (data not shown). Likewise, the results were similar when restricted to infants that did not experience birth hospital transfers (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Our results suggest that birth hospital nursery level and infants’ CCHD type are associated with late detection. Infants born in hospitals with only Level I or II nursery facilities were more likely to have late-detected CCHD compared to infants born in hospitals with Level III nursery facilities. From Table 1, it can be calculated that the rate of late detection was 37% for infants born in hospitals with Level I nurseries and 26% for infants born in hospitals with Level II nurseries – which suggests that infants born in hospitals with only Level I or II nurseries may be at substantial risk of leaving the birth hospital with an undiagnosed CCHD. One possible explanation for this association is the greater use of pulse oximetry and other diagnostic tools in higher level nurseries. However, routine pulse oximetry screening practices are focused on detecting CCHD conditions in asymptomatic newborns – newborns unlikely to be admitted to higher level nurseries prior to diagnosis. The birth cohort in our study predated the 2011 addition of screening for CCHD to the U.S. Recommended Uniform Screening Panel. In addition, although we do not have data on the use of pulse oximetry screening in Florida during our study period, a 2007 survey of pediatric cardiologists suggests a low utilization of routine pulse oximetry screening at that time.18 Another hypothesis is that hospitals with Level III nurseries may detect more cases of CCHD through prenatal diagnosis and clinical awareness relative to community hospitals;7 thus, the greatest benefit to newborn CCHD screening may accrue to infants born in community hospitals.

The prevalence of late detection varied by CCHD type. Although these conditions share the characteristic of requiring surgical or catheter intervention within the first year of life, they represent a heterogeneous grouping of conditions with varying pathology, clinical presentation and risk of hypoxemia during the birth hospitalization. This heterogeneity also has implications for routine pulse oximetry screening, with the sensitivity of screening likely variable by specific condition.19

Most of the characteristics that were significant in the bivariate analyses ceased to be significant in the multivariable models. Several maternal factors associated with late detection in the bivariate analysis were also associated with delivering in a hospital with a Level I nursery (e.g., younger maternal age, high school graduate or equivalent, and U.S.-born) and having public insurance (e.g., younger maternal age, high school graduate), suggesting these factors are possibly related to access to higher-level hospital facilities.20 The significance of preterm birth in the bivariate analyses also could have been related to hospital facility level because premature labor could lead mothers to give birth in facilities with more sophisticated nursery care and premature infants may be under increased scrutiny.21

This study was limited by several factors. First, the study could not control for the role of prenatal diagnosis in late detection because prenatal diagnosis information is not available in the FBDR. According to data provided by the Florida Department of Health’s Bureau of Community Health Assessment, the distribution of births by nursery level (defined as the highest nursery level available in the facility) was significantly different (p-value <0.001) for infants with CCHD (nursery Level I: 18.7%; Level II: 22.5%; Level III: 58.7%) compared to all infants born in the same Florida hospitals (nursery Level I: 19.6%; Level II: 31.1%; Level III: 49.3%). The increased frequency of delivery at hospitals with higher level nurseries could reflect mothers’ choices or clinical advice to attend such birth hospitals due to prenatal diagnosis of CCHD. In particular, prenatal diagnosis of CCHD might account for the gap in the frequency of late diagnosis between infants born at hospitals with Levels II and III nursery facilities. However, regardless of the explanation for the association, routine CCHD screening could reduce differences in the frequency of late diagnosis.

This study was limited also by its use of hospital-wide indicators of nursery level. It would have been preferable to examine the nursery in which an infant actually received care. Another limitation is that this study relied on administrative data based on ICD-9-CM codes, which are imperfect identifiers of CCHD conditions.22,23 Even though the FBDR uses multiple data sources to ascertain infants with birth defects, the diagnoses are not clinically verified. However, the FBDR’s overall completeness of ascertainment of birth defects has been estimated at approximately 87%, with case ascertainment variation noted by specific defect.9,10 A recent report on the prevalence of select CCHDs among birth defect surveillance programs in the United States showed that while individual programs’ birth defects prevalence estimates varied, partially due to differences in case finding, mean prevalence estimates across programs were similar for several CCHDs.24 Our dataset reflected information from one state, which limits generalizability. Lastly, we were unable to control for length of stay as a determinant of timely detection. An infant who is hospitalized longer is more likely to be detected with CCHD prior to discharge. However, because CCHD diagnosis also leads to longer length of stay, we could not use length of stay as an independent predictor. The shorter average length of stay in hospitals with Level I or II nurseries might help account for the greater frequencies of late-detected CCHD among infants in those hospitals.

The main study strengths lie in the setting and design. We used a state-wide, population-based birth defects registry data over several years. This dataset included information on all state-based hospital admissions and ICD-9-CM codes for infants identified as having CCHD. These data are from a large and racially/ethnically diverse source population. In 2010, Florida was the fourth most populous state and ranked fourth in annual number of live births in the United States.25 Florida was also third in annual live births to Hispanic women and first in annual live births to African-American women.25 Our results indicate that the study sample demographics are generally representative of the overall live-births in Florida, with the exception that infants with CCHD were more likely to have been born preterm, a common association with birth defects,26-28 and included 9% fewer Hispanic mothers than expected.13

CONCLUSION

This study assessed whether selected characteristics were associated with late CCHD detection among a population-based, state-wide cohort of infants with CCHD identified by a state birth defects registry. We found that infants born in hospitals with Level I and Level II nurseries were more likely to have a late diagnosis than infants born in hospitals with Level III nurseries. These results suggest that universal newborn screening for CCHD could be particularly beneficial for infants born in hospitals with Level I and II nurseries. Implementing universal pulse oximetry screening in these nurseries may be challenging due to resource constraints. However, in a recent study in New Jersey, where screening is currently mandated, the nursing staff reported that pulse oximetry was a familiar skill and screening all newborns for CCHD was easily added to other routine tasks.29 The N.J. study and a second study in Georgia, where screening is voluntary, found that differences in screening practices between hospitals could be reduced with more staff education.29,30

This study highlights the importance and use of birth defects surveillance data, which, along with hospital discharge data, can help inform newborn screening programs and other decisions.31 Additional population-based studies with clinically verified CCHD conditions, information on prenatal diagnosis, and conducted after pulse oximetry screening implementation could confirm these findings. Such studies could link birth defects surveillance, medical records, hospital discharge, and insurance data as well as information from prenatal care facilities in various states.

What’s Known on This Subject

Newborns with critical congenital heart disease are at risk of cardiovascular collapse or death if discharged from the birth hospital without a diagnosis. Newborn screening aims to identify critical congenital heart disease missed in prenatal and postnatal examinations.

What This Study Adds

Birth hospital nursery level and critical congenital heart disease type were found to be associated with late critical congenital heart disease detection. Routine newborn screening could conceivably reduce differences in the frequency of late diagnosis between birth hospital facilities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the staff of the Florida Department of Health’s Florida Birth Defects Registry, Children’s Medical Services Program, and Florida Agency for Health Care Administration for data accessibility and acquisition. We also thank Adrienne Henderson and Gloria Barker with the Florida Agency for Health Care Administration, Florida Center for Health Information and Policy Analysis and Karen Freeman with the Florida Department of Health for consultations on hospital discharge data and Florida hospitals. We thank Jason Salemi at the University of South Florida and Marie Bailey at the Florida Department of Health for consultations on data linkages and variables, and we thank Cora Peterson at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for consultations on study design and variables. Lastly, we acknowledge the March of Dimes Foundation for providing funding for this project (Research Grant No. #5-FY09-533).

Funding Source: This study was also supported by appointments to the Research Participation Program at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and CDC. Neither funder was involved in decisions regarding design, analysis, or interpretation of study results.

Abbreviations

- CCHD

critical congenital heart disease

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Contributor’s Statement:

April Dawson: Ms. Dawson designed the study, carried out analyses, drafted the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Cynthia H. Cassell: Dr. Cassell assisted with data acquisition, study design, interpretation of the results, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Tiffany Riehle-Colarusso: Dr. Riehle-Colarusso provided clinical oversight, assisted with interpretation of the results, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Scott D. Grosse: Dr. Grosse assisted with the interpretation of results, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Jean Paul Tanner: Mr. Tanner assisted with data acquisition and linkages, interpretation of the results, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Russell S. Kirby: Dr. Kirby assisted with data acquisition, interpretation of the results, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Sharon M. Watkins: Dr. Watkins assisted with data acquisition, interpretation of the results, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Jane A. Correia: Ms. Correia assisted with data acquisition, interpretation of the results, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Richard S. Olney: Dr. Olney provided clinical oversight, assisted with the interpretation of results, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mahle WT, Newburger JW, Matherne GP, et al. Role of pulse oximetry in examining newborns for congenital heart disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and American Academy of Pediatrics. Circulation. 2009;120(5):447–458. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thangaratinam S, Brown K, Zamora J, et al. Pulse oximetry screening for critical congenital heart defects in asymptomatic newborn babies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2012;379(9835):2459–2464. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60107-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahle WT, Martin GR, Beekman RH, et al. Endorsement of Health and Human Services recommendation for pulse oximetry screening for critical congenital heart disease. Pediatrics. 2012;129(1):190–192. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuehl KS, Loffredo CA, Ferencz C. Failure to diagnose congenital heart disease in infancy. Pediatrics. 1999;103(4 Pt 1):743–747. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.4.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang RK, Gurvitz M, Rodriguez S. Missed diagnosis of critical congenital heart disease. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(10):969–974. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.10.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peterson C, Dawson A, Grosse SD, et al. Hospitalizations and costs among infants with critical congenital heart disease: how important is timely detection? Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2013 doi: 10.1002/bdra.23165. Accepted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradshaw EA, Cuzzi S, Kiernan SC, et al. Feasibility of implementing pulse oximetry screening for congenital heart disease in a community hospital. J Perinatol. 2012;32(9):710–5. doi: 10.1038/jp.2011.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.State Birth Defects Surveillance Program Directory Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2011;91:1028–1149. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salemi JL, Tanner JP, Block S, et al. The relative contribution of data sources to a birth defects registry utilizing passive multisource ascertainment methods: does a smaller birth defects case ascertainment net lead to overall or disproportionate loss? J Registry Manag. 2011;38(1):30–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salemi JL, Tanner JP, Kennedy S, et al. A comparison of two surveillance strategies for selected birth defects in Florida. Public Health Rep. 2012;127(4):391–400. doi: 10.1177/003335491212700407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agency for Health Care Administration (AHCA) Florida Agency for Health Care Administration [Accessed September 19, 2012];2011 http://ahca.myflorida.com/. Published.

- 12.MacDorman MF, Menacker F, Declercq E. Trends and characteristics of home and other out-of-hospital births in the United States, 1990-2006. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010;58(11):1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Florida Department of Health Birth Defects Registry [Accessed September 19, 2012];Report on Birth Defects in Florida: 1998-2007. 2011 http://www.fbdr.org/pdf/FBDR_report_May2011.pdf. Published.

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Accessed December 5, 2012];Screening for Critical Congenital Heart Defects. 2012 http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/pediatricgenetics/documents/CCHD-factsheet.pdf. Published.

- 15.Kemper AR, Mahle WT, Martin GR, et al. Strategies for Implementing Screening for Critical Congenital Heart Disease. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):e1259–e1267. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn Levels of neonatal care. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):1341–1347. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang RK, Rodriguez S, Klitzner TS. Screening newborns for congenital heart disease with pulse oximetry: survey of pediatic cardiologists. Pediatr Cardiol. 2009;30(1):20–25. doi: 10.1007/s00246-008-9270-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prudhoe S, Abu-Harb M, Richmond S, et al. Neonatal screening for critical cardiovascular anomalies using pulse oximetry. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2013 Jan 22; doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-302045. Published Online First. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-302045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samuelson JL, Buehler JW, Norris D, et al. Maternal characteristics associated with place of delivery and neonatal mortality rates among very-low-birthweight infants, Georgia. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2002;16(4):305–313. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2002.00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeitlin J, Gwanfogbe CD, Delmas D, et al. Risk factors for not delivering in a level III unit before 32 weeks of gestation: results from a population-based study in Paris and surrounding districts in 2003. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2008;22(2):126–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2007.00921.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frohnert BK, Lussky RC, Alms MA, et al. Validity of hospital discharge data for identifying infants with cardiac defects. J Perinatol. 2005;25(11):737–742. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strickland MJ, Riehle-Colarusso T, Jacobs JP, et al. The importance of nomenclature for congenital cardiac disease: implications for research and evaluation. Cardiol Young. 2008;(18 Suppl 2):92–100. doi: 10.1017/S1047951108002515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mai CT, Riehle-Colarusso T, O’Halloran A, et al. Selected birth defects data from population-based birth defects surveillance programs in the United States, 2005–2009: Featuring critical congenital heart defects targeted for pulse oximetry screening. Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology. 2012;94(12):970–983. doi: 10.1002/bdra.23098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ. National vital statistics reports. 2. Vol. 60. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2011. Births: Preliminary data for 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Honein MA, Kirby RS, Meyer RE, et al. The association between major birth defects and preterm birth. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13(2):164–175. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0348-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petrini J, Damus K, Russell R, et al. Contribution of birth defects to infant mortality in the United States. Teratology. 2002;(66 Suppl 1):S3–6. doi: 10.1002/tera.90002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Purisch SE, DeFranco EA, Muglia LJ, et al. Preterm birth in pregnancies complicated by major congenital malformations: a population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(3):287 e281–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.06.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rapid implementation of pulse oximetry newborn screening to detect critical congenital heart defects — New Jersey, 2011. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2013;62(15):292–294. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Assessment of current practices and feasibility of routine screening for critical congenital heart defects — Georgia, 2012. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2013;62(15):288–291. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olney RS, Botto LD. Newborn screening for critical congenital heart disease: essential public health roles for birth defects monitoring programs. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2012;94(12):965–969. doi: 10.1002/bdra.23103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]