SUMMARY

Clinical studies on MET-targeting cancer therapeutics yielded mixed results in recent years and MET relevant predictive biomarkers remain elusive. New studies now reveal METex14 alternative splicing aberrations to represent potential predictive cancer genomic biomarkers, hence renewing optimism and directions in the quest for optimized MET-targeting personalized cancer therapy.

In this issue of Cancer Discovery, Dr. Paul Paik and colleagues reported that mutations of RNA splice acceptor and donor sites involving exon 14 of MET could lead to the exon skipping resulting in an in-frame deletion of the juxtamembrane domain, which normally is a negative regulator of the kinase catalytic activities. More important the authors provided evidence of tumor response to MET targeted therapies using crizotinib or carbozantinib [1]. Another article by Dr. Garrett Frampton and colleagues identified recurrent and diverse genomic alterations in multiple tumor types leading to MET exon 14 (METex14) alternative splicing aberrations [2]. A small case series of patients harboring METex14 aberrancy was highlighted with tumor response towards crizotinib and INC280. Since the last “In The Spotlight” article in 2011 [3] reviewing the impact of the first reported durable complete response under MetMab treatment in a patient with chemotherapy-refractory gastric cancer metastatic to the liver, much further clinical effort has been devoted in MET-targeted therapeutics, but only with mixed results upon the completion of several advanced clinical trial studies. Aberrant MET/HGF regulation is seen in wide variety of human cancers with dysregulated proliferative and invasive signaling program, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), cell motility/migration, scattering, angiogenesis, invasion and metastasis. MET/HGF signaling has also been inducted as one of the “Hallmarks of Cancer” in “activating invasion and metastasis” [4]. To put into perspectives for the two articles by Drs. Paik and Frampton in this issue [1, 2, 5], recent course of clinical trial development of MET-targeting agents is briefly reviewed below.

Built upon the success of a positive phase II clinical study revealing that the anti-MET one-arm monoclonal antibody onartuzumab (MetMab) was efficacious in advanced NSCLC patients selected for high MET expression, the phase III METLung trial was soon introduced to as a biomarker-selected study to investigate onartuzumab/erlotinib versus erlotinib/placebo in previously treated stage IIIB-IV NSCLC with centrally confirmed MET-positive expression. The phase II results strongly suggested that MET-IHC status may predict clinical benefit from onartuzumab/erlotinib combination; hence the METLung trial was designed to include patients with MET-IHC 2+/3+ in ≥50% tumor cells. However, on March 3, 2014, Roche announced termination of the phase III METLung study for reason of a lack of clinically meaningful efficacy.

Tivantinib (ARQ197) is a non-ATP–competitive small molecule targeting MET. A global randomized phase II trial ARQ197–209 initially compared erlotinib/tivantinib (ET) versus erlotinib/placebo (EP) in unselected advanced NSCLC, and found progression-free-survival (PFS) to be prolonged as the primary endpoint in ET group. Biomarker analysis demonstrated that among nonsquamous tumors, 75% were MET-positive by IHC(2+/3+), compared with only 12% among squamous subtype. Exploratory analysis demonstrated significant delay in time-to-development of new metastases among patients treated with ET (HR 0.49, P<0.01), most notable in the nonsquamous population. A global randomized phase 3 trial MARQUEE soon followed for patients with nonsquamous NSCLC histology, enriching for MET-high expression, with overall survival (OS) as primary endpoint [6]. Unfortunately, MARQUEE trial was again discontinued early after a planned interim analysis revealed study futility. Nonetheless, final analysis showed both PFS and overall response rates (ORR) were improved. Besides, tivantinib treatment group did show significant OS improvement in the subgroup with MET-high expression, essentially recapitulating the phase II MetMab study results.

Crizotinib was approved in 2011 for ALK(2p23) translocation-positive NSCLC based on its ALK activities, despite its initial development intended as a MET inhibitor. Since then, genomic MET amplification associated with various tumor types has been correlated with crizotinib treatment response [7]. A recent The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Research Network report on lung adenocarcinoma confirmed a frequency of 2.2% with also evidence as oncogene-driver alteration [8]. The first results of crizotinib treatment in MET-amplified NSCLC from the original phase I study of the dual MET/ALK inhibitor was presented in ASCO 2014 Annual Meeting with 14 patients accrued to the NSCLC cohort, predominantly with adenocarcinoma and mostly with positive smoking status. Objective partial response rates were observed: 0%, 17%, and 67% in the low-(MET/CEP7 ratio ≥1.8–≤2.2), intermediate- (ratio >2.2–<5.0), and high-MET (ratio ≥5.0) groups respectively, suggesting an improved efficacy as the MET amplification ratio increased.

Besides, MET amplification, TCGA lung adenocarcinoma study report also identified 10 tumor samples harboring METex14 skipping within the RNA, in the presence of somatic in cis DNA exon 14 splice site mutation (ss mut), splice site deletion (ss del) or a Y1003* mutation [8]. Hence, the frequency of MET exon 14 skipping in lung adenocarcinoma is determined as 4.3%. Genomic alterations involving exon 14 skipping alternative splicing of MET were first reported in 2003 and 2005 [9, 10]. Exon 14 encoding the juxtamembrane domain of MET was also found to harbor missense mutations R988C and T1010I in lung cancer which were shown activating. Novel MET exon 14 splicing variants, two in SCLC involving a 2 base-pair insertion in a splice acceptor site 5’ of exon 14 and one in a NSCLC tumor involving an in-frame skipping of exon 14 were identified [9, 10]. In 2006, Kong-Beltran et al. identified another series of somatic intronic mutations in lung cancer cell lines and patient samples immediately flanking exon 14, and Y1003 residue that serves as the juxtamembrane domain binding site for CBL, the E3-ubiquitin ligase to regulate MET receptor turnover [11]. Recently, novel chromosomal fusions involving MET kinase have been identified in various cancers. In particular, at least two fusion variants (i.e. KIF5B–MET in lung adenocarcinoma and TFG–MET in thyroid papillary carcinoma) do have the predicted chimeric protein confirming with the classic fusion activation paradigm, joining the dimerization motifs to an intact kinase domain [12]. These findings strongly suggest an oncogenic role of the MET fusion products.

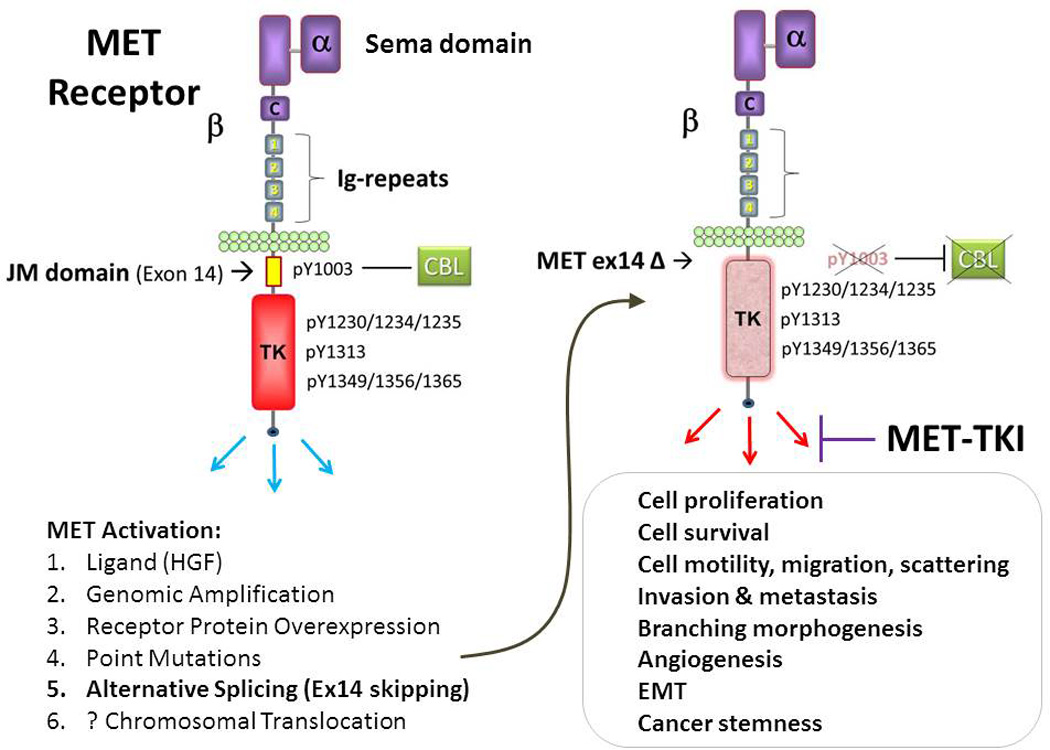

The two new articles by Paik et al. and Frampton et al. [1, 2] further enrich our understanding of MET as molecular target in precision cancer therapy (Figure 1). In the largest tumor genomic profiling cohort performed for MET alteration, Frampton et al. reported 221 positive cases (0.6%) found to express METex14 mutations out of 38,028 profiled tumors. Most interestingly, METex14 alterations comprised of a surprisingly diverse 126 distinct sequence variants, and were found most commonly but not exclusively in lung adenocarcinoma (3%), and were seen also in other lung tumor types (2.3%), brain glioma (0.4%), and tumors of unknown primary (0.4%). Both reports highlighted METex14 conferring sensitivity towards MET-targeting inhibitors with clinical response either by tumor measurement or metabolic PET response, further raising the specter of METex14 collectively as “actionable” genomic alterations and cancer predictive biomarkers. Since the juxtamembrane domain is a key negative regulatory region for the intracellular kinase domain in the human kinome, its disruption through splicing skipping in MET likely can transition the closed kinase conformation to a more open and thus active conformation, akin to the effects of oncogenic FLT3-ITD (internal tandem repeat) in AML. METex14 variants also stabilize the altered MET receptor through decreased CBL-mediated MET-ubiquitination.

Figure 1. METex14 activates oncogenic signaling and is potential MET targeting therapy cancer genomic predictive biomarker.

Wild type MET receptor is known to be activated by a variety of mechanisms including ligand HGF binding (to the ligand-binding and receptor dimerization Sema domain), genomic amplification, receptor protein overexpression, point mutations, alternative splicing and possibly chromosomal translocation. METex14 genomic variants can occur via diverse genomic aberrations involving the splice sites, resultant in in-frame skipping of the juxtamembrane domain encoding exon 14. METex14 not only can represent an important oncogenic variant, but also can serve as genomic predictive biomarker for MET-targeting therapy. C, cystein-rich region; HGF, hepatocyte growth factor; Ig-repeats 1–4, Immunoglobulin-like repeats 1–4; JM domain, juxtamembrane domain; TK, tyrosine kinase domain; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

These new findings also underscore the challenges in genomic tumor profiling: (1) therapeutically relevant alterations could reside within the intronic regions of splice sites, (2) diverse mutational alterations culminating in exon 14 skipping as common end product, and (3) potential utility in clinical RNA-seq profiling. Cancer sequencing only the exons and simple hotspot mutational sequencing panels are inadequate. Of note, the finding that METex14 skipping alterations had coexisting MET amplification is of interest and warrants further clarification. Likewise, the highly coincident genomic events of gene copy number amplification of MDM2 and CDK4 with METex14 alterations deserve further studies. To this end, in the era of genomics-guided personalized cancer therapy, it is now becoming clear that it is not only important to arrive at a genomic biomarker for patient selection, a genuine predictive biomarker should be analyzed in the context of as much genomic landscape background as possible in order to appreciate and categorize potential therapy response genomic-modifiers. An example can be illustrated by the H596 adenosquamous cell line which expresses not only the METex14 skipping variant but also PIK3CA mutation. The H596 cells were found to be insensitive to MET inhibitor alone but had synergistic sensitivity to combined MET/PI3K inhibitors treatment in preclinical models. Moreover, Liu and colleagues reported in the ASCO 2015 Annual Meeting that METex14 variants occurred frequently in pulmonary sacomatoid carcinoma at a resoundingly high 22%, and one such patient with METex14 and concurrent MET amplification displaying substantial response to crizotinib (Balazs Halmos, personal communication).

Now, the time is right to formally test in prospective clinical studies matching METex14 genomic variants with MET therapeutic agents. Clearly, other concurrent variations in MET/HGF as well as other genomic background would be important and should be deciphered simultaneously in tumor profiling, in order to enable thorough and unbiased treatment response analysis. Would METex14 tumors also respond to onartuzumab as well? Also, whether there would be response variations among different MET agents does not have easy answers unfortunately at present. We await further clinical-translational studies to yield the answers. Yet, a number of challenges and questions still remain in the road to optimizing MET cancer therapy. Is MET a legitimate molecular target for cancer therapy? Most believe “Yes” although the precise predictive biomarkers for response remain somewhat elusive. We now have more evidence to support MET amplification and METex14 alterations to be potential genomic predictive determinants; but how about MET protein (over)expression, and other MET missense mutations? Are they out of the questions already? I would argue not. In the MARQUEE study tivantinib did improve OS in the subgroup of tumors with high MET expression, suggesting for a potential efficacy in a biomarker-selected population. This particular biomarker challenge perhaps is not too dissimilar to what we are witnessing in PD-L1 expression assay under immune checkpoint therapy.

Even if all agree on MET being a legitimate target, how should we measure it as target and how should we optimally measure the treatment outcome? It is important also to point out that there is high heterogeneity of MET genomic alterations in cancer, including the large repertoire of mutations identified within the HGF and MET gene, as compiled in the cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics database (http://www.cbioportal.org/index.do), many of which have not been fully functionally tested. Besides, the spatial-temporal heterogeneity of the biomarker within the tumor itself, as well as the stromal microenvironmental influence are not trivial. I would argue that obtaining newly-biopsied pretreatment (by MET agents) tumor tissues, preferably at the site of tumor progression or metastatic site, should be a priority (if not prerequisite) for future MET-targeting trials, so that we would not be left with more questions than answers in analyzing the clinical study outcomes. Novel technologic platforms for genomic interrogation such as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and circulating tumor cells (CTC) as liquid biopsies, could be quite useful in this context to overcome the sampling errors of tissue biopsy. Novel quantitative biomarker expression assay technologies could also shed important new light in MET biomarker research. As MET/HGF pathway is known to activate tumor invasion and metastasis, and recognized as such in the “Hallmarks of Cancer”, should we critically ask whether RECIST and OS represent the proper “measuring ruler” for treatment outcome and efficacy of MET-targeting therapies? To this end, deeper insight into the impact of MET inhibition on time-to-new metastasis in future trials could be quite illuminating. Is there any justifiable ways to study and measure the clinical benefits of MET/HGF-targeting if it impact new metastasis formation and progression but less so on primary tumor growth? Our current clinical trial outcome measurement, based on the conventional definition of “disease progression”, could not readily discern these differences. How to combine MET-targeting therapy most effectively with other therapies including cytotoxic, targeted and immune therapies, to achieve the optimal clinical outcomes would thus be most worthwhile of investigations. At this time, the quest for clinical MET therapy predictive biomarkers evidently has a new beginning. We are returning to the drawing board for a new roadmap in optimized MET-targeting therapy clinical study design.

Acknowledgement

P.C.M. is supported by Mary Babb Randolph Cancer Center at the West Virginia University, West Virginia Clinical and Translational Science Institute (WVCTSI), by the National Institute Of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U54GM104942 (IDeA CTR). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Paik PK, Drilon A, Yu H, Rekhtman N, Ginsberg MS, Borsu L, Schultz N, Berger MF, Rudin CM, Ladanyi M. Response to MET inhibitors in patients with stage IV lung adenocarcinomas harboring MET mutations causing exon 14 skipping. Cancer discovery. 2015 doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frampton GM, Ali SM, Rosenzweig M, Chmielecki J, Lu X, Bauer TM, Akimov M, Bufill J, Lee C, Jentz D, Hoover R, Ou I, Salgia R, Brennan T, Chalmers Z, Elvin JA, et al. Activation of MET via diverse exon 14 splicing alterations occurs in multiple tumor types and confers clinical sensitivity to MET inhibitors. Cancer discovery. 2015 doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feng Y, Ma PC. Anti-MET targeted therapy has come of age: the first durable complete response with MetMAb in metastatic gastric cancer. Cancer discovery. 2011;1(7):550–554. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frampton GM. Comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) of advanced cancers to identify MET exon 14 alterations that confer sensitivity to MET inhibitors. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2015;33(suppl) abstr 11007). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scagliotti GV, Novello S, Schiller JH, Hirsh V, Sequist LV, Soria JC, von Pawel J, Schwartz B, Von Roemeling R, Sandler AB. Rationale and design of MARQUEE: a phase III, randomized, double-blind study of tivantinib plus erlotinib versus placebo plus erlotinib in previously treated patients with locally advanced or metastatic, nonsquamous, non-small-cell lung cancer. Clinical lung cancer. 2012;13(5):391–395. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng Y, Thiagarajan PS, Ma PC. MET signaling: novel targeted inhibition and its clinical development in lung cancer. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer. 2012;7(2):459–467. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182417e44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;511(7511):543–550. doi: 10.1038/nature13385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma PC, Kijima T, Maulik G, Fox EA, Sattler M, Griffin JD, Johnson BE, Salgia R. c-MET mutational analysis in small cell lung cancer: novel juxtamembrane domain mutations regulating cytoskeletal functions. Cancer research. 2003;63(19):6272–6281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma PC, Jagadeeswaran R, Jagadeesh S, Tretiakova MS, Nallasura V, Fox EA, Hansen M, Schaefer E, Naoki K, Lader A, Richards W, Sugarbaker D, Husain AN, Christensen JG, Salgia R. Functional expression and mutations of c-Met and its therapeutic inhibition with SU11274 and small interfering RNA in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer research. 2005;65(4):1479–1488. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kong-Beltran M, Seshagiri S, Zha J, Zhu W, Bhawe K, Mendoza N, Holcomb T, Pujara K, Stinson J, Fu L, Severin C, Rangell L, Schwall R, Amler L, Wickramasinghe D, Yauch R. Somatic mutations lead to an oncogenic deletion of met in lung cancer. Cancer research. 2006;66(1):283–289. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stransky N, Cerami E, Schalm S, Kim JL, Lengauer C. The landscape of kinase fusions in cancer. Nature communications. 2014;5:4846. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]