Abstract

Background and Objectives

It remains unknown whether the association between diabetes mellitus (DM) and cognitive function differs in Eastern and Western populations. This study aimed to elucidate whether DM is associated with worse cognitive performance in both populations.

Methods

The Shanghai Aging Study (SAS) and the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging (MCSA) are two population-based studies with similar design and methodology in Shanghai, China and Rochester, MN USA. Non-demented participants underwent cognitive testing, and DM was assessed from the medical record. Separate analyses were performed in SAS and MCSA regarding the association between DM and cognitive performance.

Results

A total of 3348 Chinese participants in the SAS and 3734 American subjects in the MCSA were included. Compared with MCSA subjects, SAS participants were younger, less educated, and had lower frequency of vascular disease, APOE ε4 carriers and obesity. Participants with DM (compared to non-DM participants) performed significantly worse on all the cognitive domains in both the SAS and MCSA. After adjustment for age, sex and education, and vascular covariates, DM was associated with worse performance in executive function (β= −0.15, p = 0.001 for SAS, and β= −0.10, p = 0.008 for MCSA) in the total sample and in the cognitively normal sub-sample. Furthermore, DM was associated with poor performance in visuospatial skills, language, and memory in the SAS, but not in the MCSA.

Conclusions

Diabetes is associated with cognitive dysfunction, in particular exerts a negative impact on executive function regardless of race, age and prevalence of vascular risk factors.

Keywords: cognition, diabetes mellitus, executive function, cross-sectional studies

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM) is estimated at 171 million worldwide, and is projected to double by 2030, resulting in a substantial increase in DM-related cognitive dysfunction. Studies that deepen the understanding of the association between DM and cognitive impairment are of pivotal importance. Previous studies, primarily on Western populations show that, DM is associated with increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia [1–3]. Cross-sectional studies suggested that DM is also associated with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [4–6] whereas results from prospective studies are inconsistent [7–9].

Most population-based studies typically examined associations of DM with diagnosis of dementia or MCI as an endpoint, rather than more sensitive psychometric testing [2, 3, 6, 10]. A possible reason is that a decline on a cognitive test score may not permit a clinical diagnosis. However, in contrast to clinical endpoints that could have been subjectively influenced, psychometric testing provides an objective assessment, which is critical when comparing different studies. Furthermore, subtle cognitive decline may be the only clinical manifestation in the very early stage of the disease process when intervention might be most effective.

The Shanghai Aging Study (SAS) and the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging (MCSA) are two independent epidemiological investigations performed separately in Chinese and American community, with similar aims, study design and methodology, thus making it feasible to perform comparative analyses. The objective of this study was to investigate the association of DM with performance in domain-specific cognitive measures in the SAS and the MCSA.

METHODS

Study Cohort

The Shanghai Aging Study was established in 2009, based on the Jingansi Community, an urban district of Shanghai, China. Subjects were identified using the government maintained “residents list”. Study coordinators went to each home to introduce the study. Eligible residents who were willing to participate were consecutively enrolled. The initial inclusion age criterion was initially ≥ 60 years old, and has recently been broadened to 50 years and older. Consequently, 3348 non-demented SAS participants were included in this study [11]. Details of these studies design and participant recruitment are described elsewhere [11–13]. The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging (MCSA) was established to estimate the prevalence and incidence of MCI and to identify risk factors for MCI and dementia[14]. At baseline, Olmsted County, Minnesota, residents aged 70–89 y on October 1, 2004, were randomly selected from an enumeration of the Olmsted County population using the Rochester Epidemiology medical records linkage system and invited to participate. Starting in 2008, additional subjects were recruited continually to maintain a sample size of approximately 2,000 participants. Since 2012, the study has been expanded to include subjects aged 50–69 years. The present analysis includes 3734 non-demented MCSA participants aged 50 years and older at recruitment.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consent

The SAS was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) of Huashan Hospital. The MCSA protocol was approved by the IRB of the Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal representative and included the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act authorization to use and disclose protected health information.

Clinical evaluation and cognition measurement

The on-site study procedures were similar for SAS and MCSA. Each participant completed an in-person evaluation including three main components: 1) An interview by a research nurse to collect demographic information, medical and neurologic history, and a risk factor profile. The interview also included a short set of questions about memory administered directly to the participant. The Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR) and the Functional assessment (Functional Activities Questionnaire [FAQ] in the MCSA, and Activities of Daily Living [ADLs] in the SAS) were administered to an informant. 2) A neurologic evaluation performed by a physician included a medical history review and a complete neurologic examination; and 3) Neuropsychological testing. In both studies, participants underwent a comprehensive neuropsychological evaluation to assess performance in memory, executive function, language, and visuospatial skills.

In the SAS, neuropsychological tests were translated, adapted and normed from western tests to harmonize with Chinese culture, relying on previous normative work and extensive experience with the measurement of cognitive abilities of the population from which the study participants were drawn, covering the aforementioned 4 domains as well: (1) memory (delayed recall from the Auditory Verbal Learning Test[15], delayed visual recall from Stick Test[16]); (2) executive function (Trail Making Test B[17], Go/No Go task[18], and Modified card sorting test[16]); (3) language (Modified Boston Naming Test[19] and Common Objects Naming Test[16]); (4) visuospatial skills (constructional copy and rotation task of Stick Test[16]). Normative data and detailed descriptions of these tests are reported elsewhere[13]. The mini-mental status test (MMSE) was used to assess global cognition.

In the MCSA, the neuropsychological battery for the 4 domains were: (1) memory (Delayed recall trials from the Auditory Verbal Learning Test[20] and Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised Logical Memory and Visual Reproduction subtests[21]; (2) executive function (Trail Making Test B[17] and Digit Symbol Substitution Test[22] from Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Revised [WAIS-R]); (3) language (Boston Naming Test[19] and Category Fluency[23]); and (4) visuospatial skill (Picture Completion and Block Design from the WAIS-R[22]).

In both the SAS and the MCSA, the results of individual tests were scaled and tests within a domain were summed and scaled to compute z-scores. This allowed comparisons across domains, and also permitted domain-specific parallel comparisons between the two cohorts, despite differences in the original cognitive measures. For each domain, at least two independent valid test scores were necessary to compute the domain score. The domain z scores were then summed and scaled to obtain a global cognitive z score. The mean and standard deviation (SD) of the z-scores in both cohorts were normalized to be 0 and 1.

Diabetes ascertainment

DM was defined as: (1) treatment for DM, (2) fasting blood glucose>126 mg/dL on 2 separate occasions[24], or (3) physician diagnosis in the participant medical record, utilizing information including self-report (SAS), medical records and fasting blood glucose (FBG) levels. In the SAS, subjects who reported a physician diagnosis of DM, currently on DM medication, or reporting DM complications were defined as having DM. The research nurse then checked the participants’ medical records, Jingansi Community DM registry database (SAS) for verification. In the MCSA, information on DM was based on abstraction of data using the Rochester Epidemiology Project medical records linkage system (MCSA), and a review of medications brought to the evaluation.

Blood sample collection and laboratory test

In the SAS and in a subset of the MCSA, overnight fast venous blood samples were collected. Fasting blood glucose (FBG) level was measured using a photometric rate reaction (Roche/Hitachi Modular Systems, Indianapolis, Indiana).

DNA was extracted and the apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotyping was conducted in the SAS[25] and the MCSA[26]. The presence of at least one ε4 allele was categorized as APOE ε4 positive.

Consensus Diagnoses

A panel of neurologists, neuropsychologists and research coordinators reviewed all the information collected for each participant and reached a consensus diagnoses of cognitively normal (CN), MCI or dementia using previously published criteria[27, 28]. The final decision was ultimately based on all the clinical information collected by the research coordinator, physician, and neuropsychological performance, taking into account education, prior occupation, personal experience and other information.

Other covariate definition

Demographic characteristics including date of birth and educational level were assessed by interview. A history of hypertension, coronary artery disease (CHD), and stroke was abstracted from the medical records. In the SAS, “stroke” included cerebral infarction/hemorrhage, transient ischemia attack and lacunar infarct; in the MCSA “stroke” only consisted of cerebral infarction/hemorrhage. Depression was assessed using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire in the MCSA and Center for Epidemiologic Studies of Depression Scale in the SAS. Body mass index (BMI) was measured by direct exam at the study visit. Obesity was defined as a body mass index ≥ 27.5 kg/m2 for SAS or ≥ 30.0 kg/m2 for MCSA[29].

Statistical analyses

Only participants who were non-demented at the baseline visit in SAS and MCSA were included in the analysis. Baseline differences were examined using Chi-square tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables. We used generalized linear models (GLM) to assess the cross-sectional associations (beta estimates [β], standard error [SE]) of DM vs. non-DM (reference group) with domain-specific and global cognitive measures (z-scores). All models were adjusted for age, sex, and education (base models). In the fully adjusted multivariable models, we adjusted for age, sex, education, APOE ε4 allele (carrier versus non-carrier), hypertension, CHD, stroke, depression and obesity.

All hypothesis testing was conducted assuming a 0.05 significance level and a two-sided alternative hypothesis. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Study sample

We included 3348 non-demented participants in SAS and 3734 from the MCSA. Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of participants. Generally, the SAS participants (compared to MCSA participants) were younger (median, 67.6 vs 76.2, p<0.0001), less educated (≤12yr, 60.8% vs 39.7%, p<0.0001), had fewer men (46.6% vs 51.3%, p<0.0001), a lower frequency of hypertension (51.3% vs 72.1%, p<0.0001), CHD (11.4% vs 37.7%, p<0.0001), depression (11.0% vs 13.0%, p=0.01), and DM (12.9% vs 18.4%, p<0.0001). In addition, SAS participants had a lower frequency of APOE ε4 carriers (17.7% vs 26.5%, p<0.0001), and a lower frequency of obesity (16.6% vs 30.8%, p<0.0001). The definition of “stroke” was different between the two studies, with the SAS including TIA/lacunar infarction whereas the MCSA did not. Thus, the SAS reported more participants with stroke (11.1% vs 5.9%, p<0.0001).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristic of SAS and MCSA

| SAS (n=3348) | MCSA (n=3734) | pa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 67.6 (62.5,75.6) | 76.2 (71.8,82.1) | <0.0001 |

| Male sex | 1561 (46.6) | 1914 (51.3) | 0.0001 |

| Education≤12y | 2034 (60.8) | 1483 (39.7) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 1712 (51.3) | 2692 (72.1) | <0.0001 |

| Strokeb | 370 (11.1) | 220 (5.9) | <0.0001 |

| Coronary Heart Disease | 379 (11.4) | 1407 (37.7) | <0.0001 |

| Depression | 367 (11.0) | 462 (13.0) | 0.0109 |

| Diabetes | 430 (12.9) | 687 (18.4) | <0.0001 |

| APOE ε4 carrier | 549 (17.7) | 962 (26.5) | <0.0001 |

| Obesityc | 554 (16.6) | 1130 (30.8) | <0.0001 |

Estimates are n (%, among non-missing) or median (Q1, Q3)

Abbreviations: SAS=Shanghai Aging Study; MCSA= Mayo Clinic Study of Aging; APOE=apolipoprotein E; BMI=body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); MMSE=mini-mental state examination, Folstein, 1987.

comparison between SAS and MCSA.

In SAS, “stroke” included cerebral infarction/hemorrhage, transient ischemia attack and lacunar infarct; in MCSA “stroke” consisted of cerebral infarction/hemorrhage, the TIA and lacunar infarct were not taken into account.

Information missing: MCSA: 1 for education, 182 for depression, 103 for APOE, 63 for BMI; SAS: 10 for HBP, 6 for Stroke, 15 for coronary heart disease, 14 for depression, 12 for DM, 238 for APOE, 10 for BMI.

Obesity was defined as BMI⩾30 kg/m2 for MCSA participants and ⩾27.5 kg/m2 for SAS participants using World Health Organization cutpoint for obesity in Asians [29].

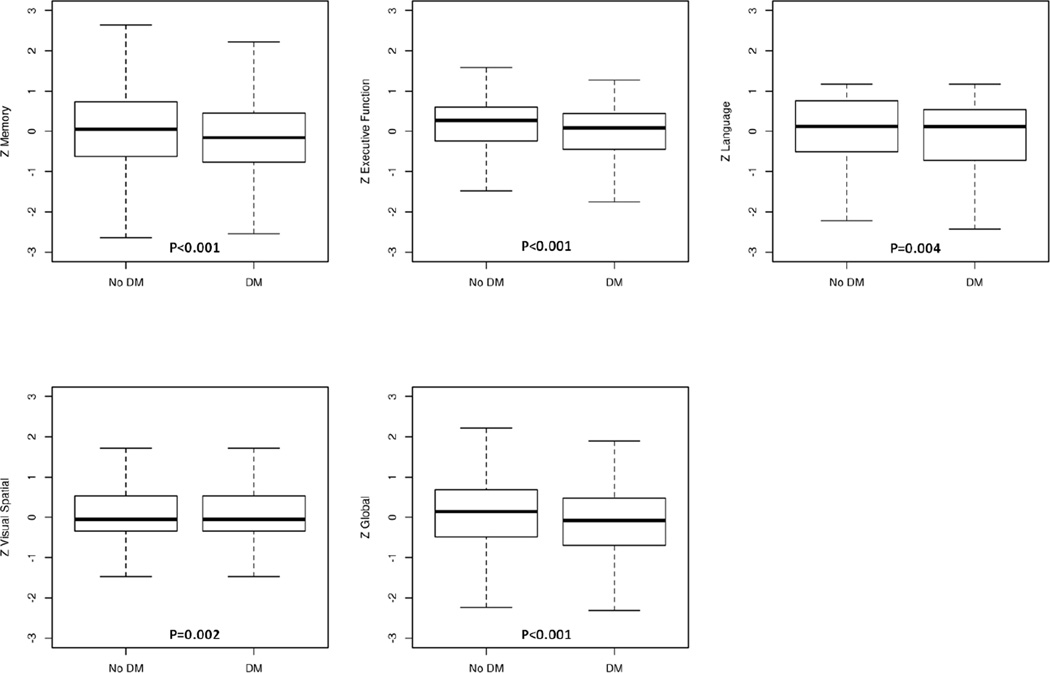

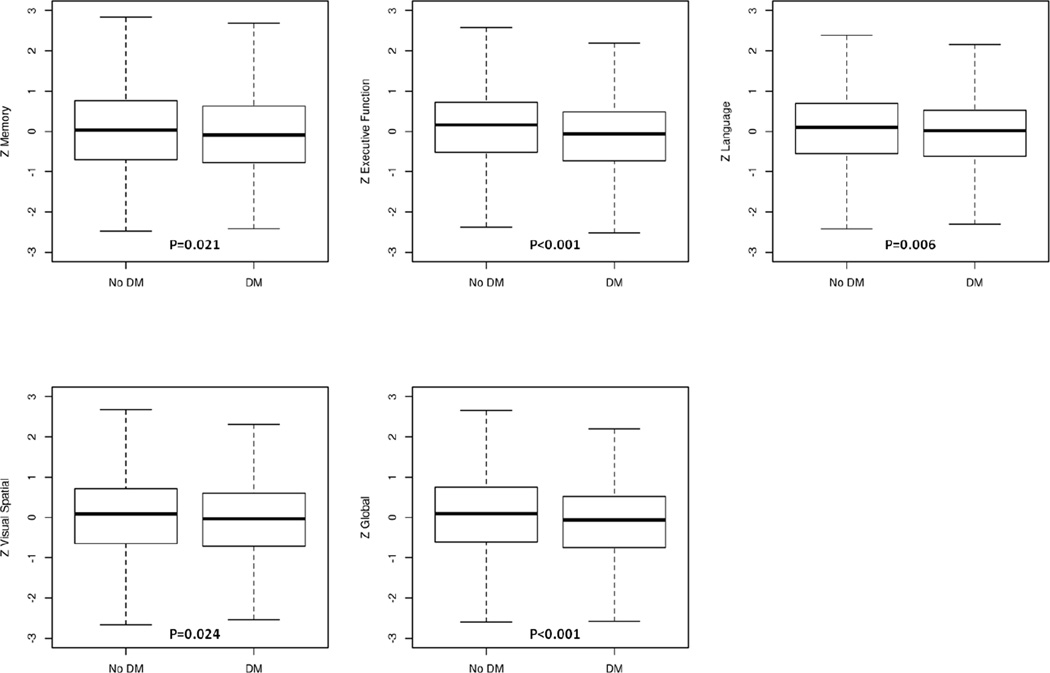

Characteristics of participants with and without DM

Table 2 shows participants with and without DM in regard to age, gender, education, vascular variables, APOE ε4 allele, and cognitive measures. In the SAS, participants with DM were older (median age 70.6 vs 67.2, p<0.0001), more frequently obese (8.9% vs 4.9%, p=0.0006), and had a higher frequency of hypertension (68.8% vs 48.7%, p<0.0001), stroke (15.8% vs 10.4%, p=0.0008), and CHD (23.1% vs 9.7%, p<0.0001) compared to those without DM. In the MCSA, similar differences were observed for DM and non-DM participants in regard to vascular risk factors and for depression (15.9% vs 12.4%, p=0.0148). MCSA DM participants were similar in age to those without DM. Participants with DM in both the SAS and MCSA performed worse on memory, executive function, visuospatial skills, language, and global cognition z-scores (p: <0.0001– 0.024), (Figures 1A, 1B).

Table 2.

Demographic, clinical and cognitive assessments for SAS and MCSA participants by diabetes status

| SAS |

MCSA |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No DM | DM | p | No DM | DM | p | |

| N | 2906a | 430a | -- | 3047 | 687 | -- |

| Age, y | 67.2 (62.3,75.4) | 70.6 (64.0,77.4) | <0.0001 | 76.2 (71.7,82.1) | 76.4 (72.2,82.2) | 0.099 |

| Male sex | 1324 (45.6) | 232 (54.0) | 0.001 | 1519 (49.9) | 395 (57.5) | 0.0003 |

| Education≤12y | 1772 (61.0) | 256 (59.5) | 0.568 | 1188 (39.0) | 295 (43.0) | 0.052 |

| Hypertension | 1414 (48.7) | 296 (68.8) | <0.0001 | 2063 (67.7) | 629 (91.6) | <0.0001 |

| Stroke | 302 (10.4) | 68 (15.8) | 0.001 | 167 (5.5) | 53 (7.7) | 0.025 |

| Coronary Heart Disease | 280 (9.7) | 99 (23.1) | <0.0001 | 1042 (34.2) | 365 (53.1) | <0.0001 |

| Depression | 318 (11.0) | 49 (11.4) | 0.786 | 358 (12.4) | 104 (15.9) | 0.015 |

| APOE ε4 carrier | 485 (17.9) | 63 (15.9) | 0.318 | 796 (26.8) | 166 (25.0) | 0.347 |

| Obesityb | 448 (15.5) | 102 (23.8) | 0.0006 | 786 (26.2) | 344 (51.0) | <0.0001 |

| Zmemory | 0.05 (−0.62,0.73) | −0.16 (−0.76,0.45) | <0.0001 | 0.03 (−0.71,0.76) | −0.09 (−0.77,0.63) | 0.021 |

| Zexecutive | 0.27 (−0.24,0.60) | 0.09 (−0.44,0.44) | <0.0001 | 0.16 (−0.53,0.72) | −0.06 (−0.73,0.49) | <0.0001 |

| Zlanguage | 0.12 (−0.51,0.76) | 0.12 (−0.72,0.54) | 0.004 | 0.10 (−0.55,0.70) | 0.02 (−0.61,0.53) | 0.006 |

| Zvisuospatial | −0.05 (−0.35,0.54) | −0.05 (−0.35,0.54) | 0.002 | 0.09 (−0.65,0.71) | −0.03 (−0.72,0.60) | 0.024 |

| Zglobal | 0.14 (−0.49,0.69) | −0.08 (−0.70,0.47) | <0.0001 | 0.10 (−0.61,0.75) | −0.07 (−0.75,0.52) | 0.0002 |

Estimates are n (%, among non-missing) or median (Q1, Q3)

Abbreviations: DM=diabetes mellitus; SAS, Shanghai Aging Study; MCSA, Mayo Clinic Study of Aging; APOE, apolipoprotein E; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared)

Totals don’t sum to 3348 because diabetic information is missing for 12 participants in Shanghai Aging Study.

Obesity was defined as BMI⩾30 kg/m2 for MCSA participants and ⩾27.5 kg/m2 for SAS participants using World Health Organization cutpoint for obesity in Asians [29].

In both SAS and MCSA, multiple neuropsychological tests were administered on each cognitive domain. The results of individual tests are scaled, scores within a domain are summed and scaled again to obtain z-scores. If the performance on a test is one standard deviation below the mean of the reference group, the z-score is −1. Zmemory, Zexecutive, Zlanguage, Zvisuospatial, Zglobal represent the z-scores for memory, executive function, language, visuospatial ability, and global cognitive function, respectively.

Information missing: MCSA: 1 for education in DM, 182 for depression (149 in No DM, 33 in DM), 103 for APOE (79 in No DM, 24 in DM), 63 for BMI (50 in No DM, 13 in DM), 51 for memory (43 in No DM, 8 in DM), 169 for executive function (123 in No DM, 46 in DM), 132 for language (99 in No DM, 33 in DM), 177 for visuospatial (128 in no DM, 49 in DM), 249 for global (186 in No DM, 63 in DM); SAS: 1 for Stroke in No DM, 9 for coronary heart disease (8 in No DM, 1 in DM), 11 for depression (10 in No DM, 1 in DM), 232 for APOE (199 in No DM, 33 in DM), 10 for BMI (8 in No DM, 2 in DM), 121 for memory (97 in No DM, 24 in DM), 65 for executive function (52 in No DM, 13 in DM), 166 for language (146 in No DM, 20 in DM), 25 for visuospatial (15 in No DM, 10 in DM), 282 for global (241 in No DM, 41 in DM).

Figure 1.

A Box-plots of domain-specific z-scores among Shanghai Aging Study participants by diabetes status

Abbreviations: DM=diabetes mellitus; No DM=participants without diabetes; SAS=Shanghai Aging Study.

The results of individual tests are scaled; tests within a domain are summed and scaled again to obtain z-scores. Zmemory, Zexecutive function, Zlanguage, Zvisuospatial, Zglobal represent the cognitive z-scores for memory, executive function, language, visuospatial ability, and global cognitive function, respectively.

B Box-plots of domain-specific z-scores among MCSA participants by diabetes status

Abbreviations: DM=diabetes mellitus; No DM=participants without diabetes; MCSA=Mayo Clinic Study of Aging.

The results of individual tests are converted to z-scores and summed per domain. Zmemory, Zexecutive function, Zlanguage, Zvisuospatial, Zglobal represent the cognitive measures for memory, executive function, language, visuospatial ability, and global cognitive function, respectively.

Cross-sectional associations of DM with cognition using GLM analysis

Table 3 shows the results of the GLM analysis in basic (adjusted for age, gender, education) and full models (further adjusted for APOE, hypertension, depression, stroke, CHD, BMI) for the association between DM and cognitive measures. The analyses were conducted in total sample and in the CN only.

Table 3.

Cross-sectional associations of DM with cognitive measures in total and cognitively normal subjects

| Non-demented (MCI+CN) |

CN only |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAS | MCSA | SAS | MCSA | ||||||

| Basic modela | Full modelb | Basic modela | Full modelb | Basic modela | Full modelb | Basic modela | Full modelb | ||

| Zmemory | β (SE) | −0.10 (0.05) | −0.10 (0.05) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.11 (0.05) | −0.11 (0.05) | −0.02 (0.04) | −0.02 (0.04) |

| p | 0.046 | 0.040 | 0.802 | 0.801 | 0.013 | 0.022 | 0.645 | 0.596 | |

| Zexecutive | β (SE) | −0.13 (0.05) | −0.15 (0.05) | −0.14 (0.04) | −0.10 (0.04) | −0.84 (0.04) | −0.09 (0.04) | −0.11 (0.03) | −0.09 (0.04) |

| p | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.0001 | 0.008 | 0.029 | 0.020 | 0.0009 | 0.018 | |

| Zlanguage | β (SE) | −0.10 (0.05) | −0.13 (0.05) | −0.05 (0.04) | −0.03 (0.04) | −0.08 (0.05) | −0.08 (0.05) | −0.07 (0.04) | −0.05 (0.04) |

| p | 0.039 | 0.012 | 0.187 | 0.437 | 0.105 | 0.098 | 0.077 | 0.231 | |

| Zvisuospatial | β (SE) | −0.12 (0.05) | −0.15 (0.05) | −0.06 (0.04) | −0.05 (0.04) | −0.12 (0.05) | −0.14 (0.05) | −0.08 (0.04) | −0.07 (0.04) |

| p | 0.020 | 0.004 | 0.101 | 0.251 | 0.010 | 0.005 | 0.030 | 0.087 | |

| Zglobal | β (SE) | −0.15 (0.05) | −0.17 (0.05) | −0.08 (0.04) | −0.07 (0.04) | −0.14 (0.04) | −0.15 (0.04) | −0.10 (0.03) | −0.08 (0.04) |

| p | 0.001 | 0.0003 | 0.023 | 0.082 | 0.0009 | 0.0005 | 0.004 | 0.019 | |

GLM model adopted. Diabetes was the independent variable in each model.

Abbreviations: DM=diabetes mellitus; MCI: mild cognitive normal; NC: cognition within normal range; SAS=Shanghai Aging Study; MCSA=Mayo Clinic Study of Aging.

adjusted for age, gender, and education as the covariates.

adjusted for age, gender, education, apolipoprotein E, hypertension, depression, stroke, coronary heart disease, body mass index.

In the total sample which included individuals with CN and MCI, both the SAS and MCSA, showed a concordant, inverse association between DM and executive function, in both the basic and fully-adjusted models. Global cognition showed a similar trend except for marginal significance for MCSA in full model (p=0.08). In the SAS, DM was associated with poor performance in visuospatial skills, language, and memory (p value: 0.004–0.046). In the MCSA, however, DM was not associated with these three cognitive domains in the basic or fully adjusted models (p>0.05).

We examined the potential interaction of APOE ε4 with diabetes. In the SAS, we found no significant interactions. In the MCSA, however, there was a significant interaction of diabetes with APOE ε4 allele for the memory domain (p for interaction = 0.008). Compared to subjects without diabetes or an APOE ε4 allele, the β(SE) estimates were −0.23 (0.04), p <0.0001 for persons with no diabetes and an APOE ε4 allele, and −0.07 (0.04), p = 0.10 for diabetes and no ε4 allele, and −0.07 (0.07), p = 0.30 for diabetes and an ε4 allele, suggesting the strongest effect with having an APOE ε4 allele.

We also performed the analyses with diabetics by severity of diabetes defined by fasting blood sugar, HBA1c and duration of diabetes (Tables S1–S3). In general, there were stronger inverse associations of either memory, or executive function, or global z scores in subjects with higher fasting blood sugar, HBA1C, and longer duration of diabetes in the SAS; and also with executive function and global z scores and HBA1C in the MCSA.

In the combined SAS and MCSA cohorts, there was increasingly worse performance in executive function and global z scores across treatment categories from no treatment or diet only, oral hypoglycemic, insulin treatment (strongest inverse association) compared to no diabetes (Table S4).

In analysis restricted to CN subjects only, we found a significant association between DM and executive function and global cognition for both SAS and MCSA, in the basic and the full models, consistent with full sample. In the SAS, DM was associated with worse performance in memory and visuspatial skills, but not associated with language. In the MCSA, DM was associated with visuospationl skills in the basic model (with a borderline association in the fully adjusted model), but was not associated with memory or language.

DISCUSSION

The SAS and MCSA were two independent cognition-oriented investigations in Eastern and Western countries. Parallel analysis indicated that DM was negatively associated with the performance on executive function and global cognition, regardless of the study population. Similar results were observed in both total population and CN only participants. After adjustment for various covariates using GLM, DM was still associated with all the domain-specific and global z-scores in the SAS. The significant association between DM and visuospatial skills diminished in the MCSA.

Our findings suggest that impairment in executive function is an important component of cognitive impairment among individuals with DM. Individuals with DM in both the SAS and MCSA samples demonstrated considerably worse performance in executive function compared to non-DM participants, consistent with previous reports [1, 30, 31]. In a large sample of 1900 non-demented people in a population-based study, subjects with diagnosed diabetes had worse executive function and slower processing speed compared to normoglycemics [32] In a cross-sectional study of 563 elderly diabetics, decreasing hemoglobin A1c level was associated with improvement in executive function [[1, 30, 31]; the study did not include non-diabetics as in the present study thus the estimates magnitude of the differences may have been biased toward the null. In small study (n=40) of elderly diabetics and non-diabetics (a convenience sample), diabetics performed worse on the test of executive function compared to non-diabetics [33]. In contrast to these studies that used a single test to assess executive function, we measured executive function from a composite of two tests. Another study showed no differences in cognitive measures in diabetic and non-diabetic controls, however, diabetic statin users had worse performance on tests of executive function, suggesting potentially worse vascular disease that could impact executive function [34]. Previous reports on neuropsychological testing in DM versus non-DM have varied from comparisons of a single test [35, 36] to a comprehensive battery [37–39]. Generally, population-based studies tend to use briefer tests, while hospital-based research utilizes a more detailed battery. Executive function is an umbrella term including reasoning, mental flexibility, and problem solving, as well as planning and decision making. Both studies used Trail Making Test B, which measures mental flexibility and the ability to “shift set”. The SAS also includes “Go-no Go” test for sustained attention and response control, in addition to “modified card sorting test” for reasoning and planning. The MCSA used the “Digit Symbol Substitution test” to measure attention and psychomotor speed. Taken together, the common and different tests of executive function in the two studies confirmed and complemented each other.

The SAS and the MCSA showed differences in the GLM analysis. The SAS was designed to recruit participants older than 60 years at baseline, whereas the MCSA enrolled participants aged 70–89 years from 2004 through 2012. Although both studies subsequently revised the inclusion criteria to recruit younger participants, the MCSA participants in the present analyses are significantly older than the SAS participants. Nearly half of SAS participants (48.2%) were aged between 60–69 years, whereas the majority of MCSA participants (46.0%) were 70–79 years. Consequently, the age at onset of DM is earlier (median 61.0 vs. 66.5 years, p<0.0001) in the SAS. In the SAS sample, we might see the insult of DM in a relatively younger population, and within a relatively earlier time frame, which might be missed in the MCSA. It has been hypothesized that midlife exposure of vascular risk is associated with a higher risk of cognitive impairment than late life onset [40]. In a recently published study among MCSA participants, midlife onset of DM was found to affect late-life cognition through loss of brain volume, while late-life onset had fewer effects on brain pathology and cognition; in addition, midlife but not late life onset, was associated with MCI [41]. Whether the age discrepancy contributes to the different multivariate results in the SAS and the MCSA remains uncertain. However, it demonstrates the importance of assessing vascular risk factors in a time-specific manner. Another explanation could be that, apart from DM, the MCSA participants also had a greater vascular burden than the SAS subjects. For instance, the frequence of hypertension in the SAS and the MCSA were 51.3% vs 72.1%, respectively (p<0.0001). Thus, even in subjects without DM, greater burden and severity of vascular factors could still exert detrimental effects on cognition, and could thereby bias the association between DM and cognition in the MCSA toward the null. Alternatively, the GLM analysis adjusting for these covariates, which are likely in the causal pathway, might result in over-controlling and bias of estimates toward the null. Other possibilities include differences in degree of DM control, disease severity, DM complications, and treatment with insulin. We did not have sufficient information to assess these differences between the groups and their potential impact on study findings. Furthermore, greater non-participation by persons with DM at baseline could have contributed to higher participation in those with less severe DM [12]. However, despite the absence of associations of DM with memory, language and visuospatial skills in MCSA participants, the association with the global score was significant, confirming that the poorer performance in the 3 domains observed in the bivariate analyses contribute to impaired performance observed in global score.

Both the SAS and MCSA focused on the non-demented population, thereby excluding dementia cases from the present analysis. Multivariate analyses performed in both total samples of CN and MCI subjects, and in CN only, yielded similar results. This suggests that even in participants whose cognitive performance were within the normal range, DM had an adverse impact on cognition. It’s known that DM is related to Alzheimer’s disease and possibly to MCI [4–6, 9]. The results in CN subjects suggest that DM has an early adverse impact on cognition that this is evident even in those who are cognitively normal. We observed a mild to moderate detrimental effect of DM on cognition, with the effect sizes ranging from 0.10–0.25 standard deviation (SD). This is slightly lower than reported for hospital-based studies [31, 42], and is understandable considering the potential sample selection bias in clinic-based studies that typically include subjects with more severe disease. Moreover, according to our previous comparison between the participants and non-participants in the two study samples [12, 13], the non-participants or telephone-interviewed subjects were older and had more vascular comorbidities which would have biased our estimates. Hence, the current estimates may more likely reflect the true associations. Nevertheless, given the results in the present study, the differences in cognitive scores between the DM and non-DM were relatively small and should be interpreted with caution when translated into the clinical setting.

Strengths of this study include the relatively large and diverse samples of Eastern and Western study participants. With a comprehensive neuropsychological exam and detailed risk factor profiles, we were able to perform domain-specific cognition analysis, adjusting for several potential confounders simultaneously. There are, however, important limitations as well. The cross-sectional nature of the study prohibits us from investigating the causal relationship.

This study supports the hypothesis that older adults with DM have reduced cognitive function, especially in the executive function domain, and this finding is consistent in both Chinese and Americans with northern European ancestry (98.7% were Caucasian), regardless of the different age and vascular burdens. Prospective studies on the longitudinal outcomes of DM in non-demented persons are underway to further elucidate the clinical relevance and implications of DM-associated cognitive dysfunction in the community setting.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dr. Minhua Shao for her technical assistance in the APOE genotype assays, Zhaolan Ding, Yan Zhou, Meihua Jin, Lirong Yu, Li Zheng, Meirong Chen, for their efforts to the study, and all the participants for their cooperation. In addition, the authors thank Ms. Mary Dugdale, RN and Ms. Connie Fortner, RN, and Ms. Julie Gingras, RN for abstraction of medical record data for the MCSA.

The study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health U01 AG006786, P50 AG016574, K01 AG028573, K01 MH068351, and R01 AG034676; the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Harold Amos Program), and the Robert H. and Clarice Smith and Abigail Van Buren Alzheimer’s Disease Research Program, the Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research; the Science & Technology Committee, Shanghai, China (09DZ1950400), the Natural Science Foundation of China (81200835), the National 973 Project of China (2013CB530900, 2013CB530904, 2011ZX09307-001-03), and the National Key Technology Project (2011ZX09307-001).

References

- 1.Biessels GJ, Deary IJ, Ryan CM. Cognition and diabetes: a lifespan perspective. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:184–190. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peila R, Rodriguez BL, Launer LJ. Type 2 diabetes, APOE gene, and the risk for dementia and related pathologies: The Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Diabetes. 2002;51:1256–1262. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.4.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ott A, Stolk RP, van Harskamp F, Pols HA, Hofman A, Breteler MM. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of dementia: The Rotterdam Study. Neurology. 1999;53:1937–1942. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.9.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Artero S, Ancelin ML, Portet F, Dupuy A, Berr C, Dartigues JF, Tzourio C, Rouaud O, Poncet M, Pasquier F, Auriacombe S, Touchon J, Ritchie K. Risk profiles for mild cognitive impairment and progression to dementia are gender specific. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:979–984. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.136903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atti AR, Forlani C, De Ronchi D, Palmer K, Casadio P, Dalmonte E, Fratiglioni L. Cognitive impairment after age 60: clinical and social correlates in the Faenza Project. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;21:1325–1334. doi: 10.3233/jad-2010-091618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roberts RO, Geda YE, Knopman DS, Christianson TJ, Pankratz VS, Boeve BF, Vella A, Rocca WA, Petersen RC. Association of duration and severity of diabetes mellitus with mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:1066–1073. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.8.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solfrizzi V, Panza F, Colacicco AM, D’Introno A, Capurso C, Torres F, Grigoletto F, Maggi S, Del Parigi A, Reiman EM, Caselli RJ, Scafato E, Farchi G, Capurso A. Vascular risk factors, incidence of MCI, and rates of progression to dementia. Neurology. 2004;63:1882–1891. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000144281.38555.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luck T, Luppa M, Briel S, Matschinger H, Konig HH, Bleich S, Villringer A, Angermeyer MC, Riedel-Heller SG. Mild cognitive impairment: incidence and risk factors: results of the leipzig longitudinal study of the aged. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1903–1910. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Geda YE, Cha RH, Pankratz VS, Baertlein L, Boeve BF, Tangalos EG, Ivnik RJ, Mielke MM, Petersen RC. Association of diabetes with amnestic and nonamnestic mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacKnight C, Rockwood K, Awalt E, McDowell I. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of dementia, Alzheimer’s disease and vascular cognitive impairment in the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2002;14:77–83. doi: 10.1159/000064928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding D, Zhao Q, Guo Q, Meng H, Wang B, Yu P, Luo J, Zhou Y, Yu L, Zheng L, Chu S, Mortimer JA, Borenstein AR, Hong Z. The Shanghai Aging Study: study design, baseline characteristics, and prevalence of dementia. Neuroepidemiology. 2014;43:114–122. doi: 10.1159/000366163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts RO, Geda YE, Knopman DS, Cha RH, Pankratz VS, Boeve BF, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Petersen RC, Rocca WA. The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging: design and sampling, participation, baseline measures and sample characteristics. Neuroepidemiology. 2008;30:58–69. doi: 10.1159/000115751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding D, Zhao Q, Guo Q, Meng H, Wang B, Luo J, Mortimer JA, Borenstein AR, Hong Z. Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment in an urban community in China: A cross-sectional analysis of the Shanghai Aging Study. Alzheimers Dement. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petersen RC, Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Geda YE, Cha RH, Pankratz VS, Boeve BF, Tangalos EG, Ivnik RJ, Rocca WA. Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment is higher in men. The Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Neurology. 2010;75:889–897. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f11d85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo Q, Zhao Q, Chen M, Ding D, Hong Z. A comparison study of mild cognitive impairment with 3 memory tests among Chinese individuals. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:253–259. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181999e92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lezak MDHD, Loring DW, editors. Neuropsychological Assessment. 4th Edition. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.RM R. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an indicator of organic brain damage. Percept Motor Skills. 1958;8:6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dubois B, Slachevsky A, Litvan I, Pillon B. The FAB: a Frontal Assessment Battery at bedside. Neurology. 2000;55:1621–1626. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.11.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan EFGH, Weintraub S, editors. The Boston Naming Test. ed 2. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ivnik RJMJ, Smith GE, et al. WAISR, WMS-R and AVLT norms for ages 56 through 97. Clin Neuropsychol. 1992;6:104. [Google Scholar]

- 21.DA W, editor. Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 22.DA W, editor. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised. New York: Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lucas JA, Ivnik RJ, Smith GE, Bohac DL, Tangalos EG, Graff-Radford NR, Petersen RC. Mayo’s older Americans normative studies: category fluency norms. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1998;20:194–200. doi: 10.1076/jcen.20.2.194.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morey SC. ADA recommends a lower fasting glucose value in the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Am Fam Physician. 1997;56:2128, 2130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koch W, Ehrenhaft A, Griesser K, Pfeufer A, Muller J, Schomig A, Kastrati A. TaqMan systems for genotyping of disease-related polymorphisms present in the gene encoding apolipoprotein E. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2002;40:1123–1131. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2002.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hixson JE, Vernier DT. Restriction isotyping of human apolipoprotein E by gene amplification and cleavage with HhaI. J Lipid Res. 1990;31:545–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th Edition. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, Jelic V, Fratiglioni L, Wahlund LO, Nordberg A, Backman L, Albert M, Almkvist O, Arai H, Basun H, Blennow K, de Leon M, DeCarli C, Erkinjuntti T, Giacobini E, Graff C, Hardy J, Jack C, Jorm A, Ritchie K, van Duijn C, Visser P, Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment--beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med. 2004;256:240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363:157–163. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCrimmon RJ, Ryan CM, Frier BM. Diabetes and cognitive dysfunction. Lancet. 2012;379:2291–2299. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nguyen HT, Arcury TA, Grzywacz JG, Saldana SJ, Ip EH, Kirk JK, Bell RA, Quandt SA. The association of mental conditions with blood glucose levels in older adults with diabetes. Aging Ment Health. 2012;16:950–957. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2012.688193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saczynski JS, Jonsdottir MK, Garcia ME, Jonsson PV, Peila R, Eiriksdottir G, Olafsdottir E, Harris TB, Gudnason V, Launer LJ. Cognitive impairment: an increasingly important complication of type 2 diabetes: the age, gene/environment susceptibility--Reykjavik study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:1132–1139. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alvarenga PP, Pereira DS, Anjos DM. Functional mobility and executive function in elderly diabetics and non-diabetics. Rev Bras Fisioter. 2010;14:491–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goh DADY, Lee WY, Koay WI, Tay SZ, Soon D, Chen C, Brittain CF, Lowe SL, Wong BS. A pilot study to examine the correlation between cognition and blood biomarkers in a Singapore Chinese male cohort with type 2 diabetes mellitus. PLoS One. 2014;9:e96874. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yaffe K, Falvey C, Hamilton N, Schwartz AV, Simonsick EM, Satterfield S, Cauley JA, Rosano C, Launer LJ, Strotmeyer ES, Harris TB. Diabetes, glucose control, and 9-year cognitive decline among older adults without dementia. Arch Neurol. 2012;69:1170–1175. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2012.1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grodstein F, Chen J, Wilson RS, Manson JE. Type 2 diabetes and cognitive function in community-dwelling elderly women. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1060–1065. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luchsinger JA, Reitz C, Patel B, Tang MX, Manly JJ, Mayeux R. Relation of diabetes to mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:570–575. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.4.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yaffe K, Blackwell T, Kanaya AM, Davidowitz N, Barrett-Connor E, Krueger K. Diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, and development of cognitive impairment in older women. Neurology. 2004;63:658–663. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000134666.64593.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van den Berg E, Reijmer YD, de Bresser J, Kessels RP, Kappelle LJ, Biessels GJ. A 4 year follow-up study of cognitive functioning in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2010;53:58–65. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1571-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reijmer YD, van den Berg E, Ruis C, Kappelle LJ, Biessels GJ. Cognitive dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2010;26:507–519. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roberts RO, Knopman DS, Przybelski SA, Mielke MM, Kantarci K, Preboske GM, Senjem ML, Pankratz VS, Geda YE, Boeve BF, Ivnik RJ, Rocca WA, Petersen RC, Jack CR., Jr Association of type 2 diabetes with brain atrophy and cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2014;82:1132–1141. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palta P, Schneider AL, Biessels GJ, Touradji P, Hill-Briggs F. Magnitude of cognitive dysfunction in adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of six cognitive domains and the most frequently reported neuropsychological tests within domains. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2014;20:278–291. doi: 10.1017/S1355617713001483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.