Abstract

Many transcriptional activators act at a distance from core promoter elements and work by recruiting RNA polymerase through protein-protein interactions. We show here how the prokaryotic regulatory protein CueR both represses and activates transcription by differentially modulating local DNA structure within the promoter. Structural studies reveal that the repressor state slightly bends the promoter DNA, precluding optimal RNA polymerase-promoter recognition. Upon binding a metal ion in the allosteric site, CueR switches into an activator conformation. It maintains all protein-DNA contacts but introduces torsional stresses that kink and undertwist the promoter, stabilizing an A-DNA-like conformation. These factors switch on and off transcription by exerting dynamic control of DNA stereochemistry, reshaping the core promoter and making it a better or worse substrate for polymerase.

While transcription factors can introduce kinks, bends (1), or loops in DNA (2), the mechanistic roles of such distortions are not always clear. Factors in the prokaryotic MerR family alter DNA structure between the core promoter elements where they repress and activate transcription in response to many signals, including metal ion concentration changes (3, 4). The activator conformation of MerR proteins introduces a DNA distortion at the center of the operator (3, 5–7) and structural studies of the activator protein-DNA complexes reveal a kink at this site (8–10). This distortion is thought to stimulate transcription by realigning the suboptimally-spaced −10 and −35 core promoter elements (fig. S1A); however, the mechanisms of allosteric conversion, repression and activation remain unknown. To understand how a protein can switch transcription off and on while bound to a single site, we solved the structures of the DNA complexes of Escherichia coli(E. coli) CueR in the repressor and activator conformation s.

CueR, a member of the metalloregulatory subfamily of MerR proteins, is a CuI and AgI-sensing factor that controls expression of metal homeostasis genes copA and cueO (11–15). The metal-bound state, AgI-CueR (i.e. activator), co-crystallized with a 23 base pair (bp) DNA based on E. coli copA promoter, PcopA (table S1, figs. S1, S2). Given the extreme affinity of CueR for copper (Kd = 2 x10−21 M) (12), crystallization of the metal free (i.e. repressor) complex required mutation of metal-binding residues (C112S, C120S) and deletion of residues disordered in the DNA-free AgI-CueR structure (C129-G135) (12). This variant is a repressor in the presence or absence of copper and co-crystallized with a 26 bp PcopA DNA (table S1, figs. S1, S2). Both structures were solved using molecular replacement (MR) and single-wavelength anomalous diffraction (SAD): the activator and repressor complexes were refined to 2.8 Å and 2.1 Å, with final models that include CueR residues 1–130 and 1–111, respectively (Figs. 1A, B; table S2)

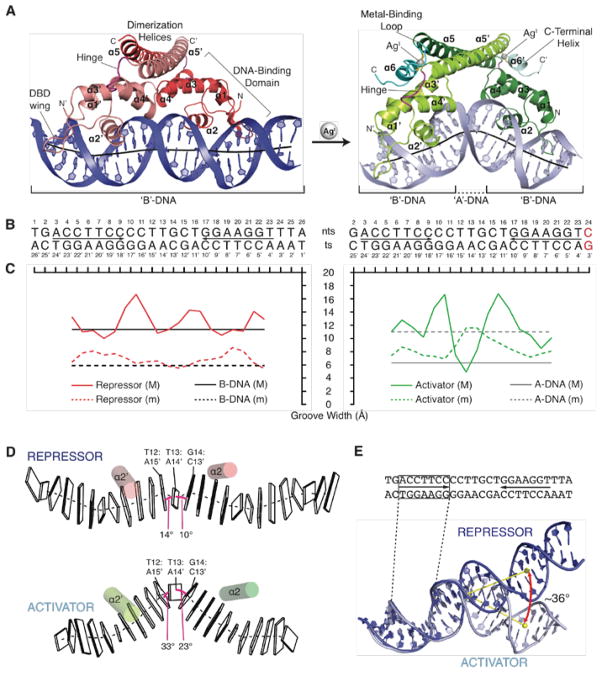

Fig. 1. Crystal Structures of Repressor and Activator Complexes with DNA.

(A) Repressor and activator CueR/DNA structures. (B) Sequences of crystallized DNA duplexes. (C) DNA groove widths (M=major groove; m=minor groove). (D) Kinks at the central bp-steps. The minor grooves are shaded black and kinks are defined by the roll angles (pink lines) between the bp-steps. (E) The activator introduces a ~36° angular change in the DNA.

In both structures, the protein is a dimer with each protomer contacting the duplex via an N-terminal DNA-binding domain (DBD) composed of four α-helices in a winged helix-turn-helix motif (Fig. 1A). A hinge loop connects the DBD to a long dimerization helix (DH). In the activator structure, the DH is followed by a metal -binding loop (MBL) and a two-turn C-terminal α-helix (CTH) (Figs. 1A, S3A, B). These features, as well as the AgI coordination, are similar in the presence and absence of DNA (fig. S3C–F) (12). As discussed below, the MBL and CTH are disordered in the repressor complex.

The most striking difference between these complexes is the DNA conformation. The stereochemistry of the central seven base pairs, which are B-form DNA in the repressor complex, switches in the activator complex to an A-DNA-like structure known as TA-DNA, first described for the TBP/DNA complex (fig. S4A–F, table S3) (16). The two central bp-steps (T12T13 and T13G14) in the repressor complex exhibit elevated roll angles (14° and 10°), consistent with a slight distortion at the center of the DNA. These become highly kinked (33° and 23°) as the minor groove becomes significantly wider than the major groove in the activator complex (Fig. 1C, D) and alters the trajectory of the helical axis by ~36° relative to the repressor complex DNA (Fig. 1E). The repressor undertwists the DNA by ~50° and the activator further undertwists the DNA by ~22°, for a total of ~72° (fig. S5 A). Other MerR-family activator/DNA complexes show similar distortions (table S3, fig. S5B) (8, 10). Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations reveal that the activator duplex structure rapidly relaxes to B-form DNA upon removal of protein constraints, supporting the idea that the DNA distortions are energetically distinct states that are stabilized by two different protein conformations (fig. S6).

Remarkably, protein-DNA contacts in repressor and activator complexes are indistinguishable in the two structures. CueR interacts with phosphate groups at the distal edges of the pseudo-palindrome through three Arg residues from α2 and the loop wing of the DBDs (Arg18, 31 and 37) that serve as clamps that “grip” the DNA backbone (i.e. R-clamps) (figs. S7A, B). Mutagenesis and functional assays reveal that all three residues are required for transcription activation (figs. S7C, D). We conclude that these conserved R-clamp residues (fig. S8) (8–10) play a key role as the activator conformation exerts the torque needed to distort the duplex into the A-DNA-like conformation.

In terms of DNA recognition, Tyr36 inserts into the minor groove and forms H-bonds to N2 of G22/23′ and O4′ of T23/24′. Lys15 inserts into the major groove and forms H-bonds to N7 and O6 of G18/19′ and N7 of G17/18′ (fig. S7B) and may confer DNA-binding site specificity (10). These interactions are not conserved among E. coli MerR proteins (fig. S8). A conserved feature among MerR proteins is the van der Waals (VDW) packing of an aromatic residue against a base in the major groove (8–10). In both CueR/DNA structures, the aromatic ring of Phe19 sits perpendicular to and forms VDW contacts with C15 and G16′ (fig. S7B). This appears to contribute to the stability of the activator state (10); however these interactions are unchanged in the repressor complex. Thus, the transcriptional switching event is not explained by changes in individual side-chain interactions with DNA.

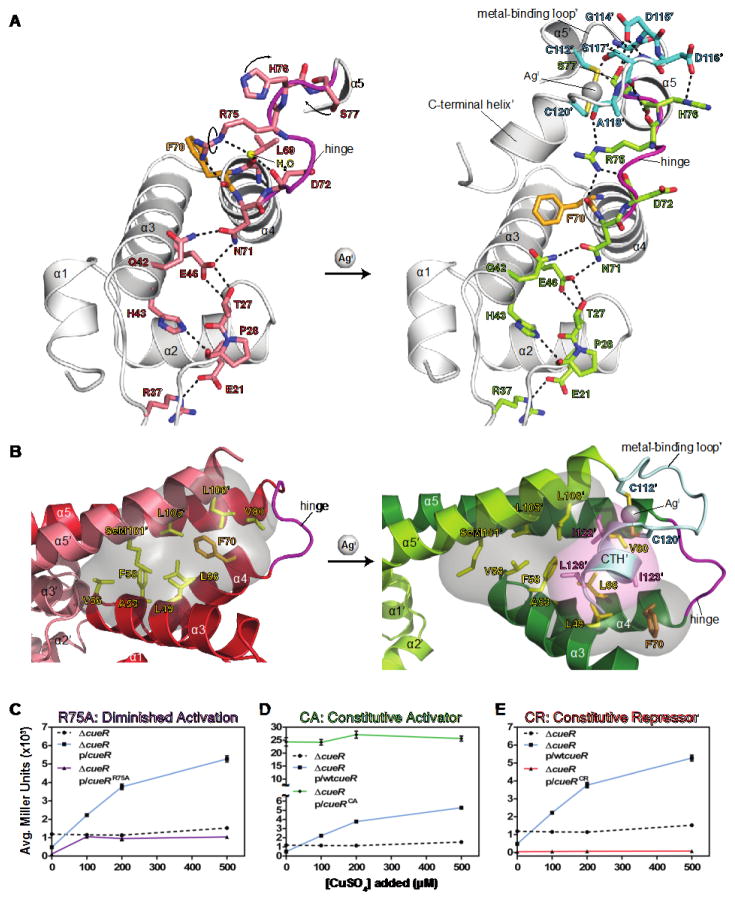

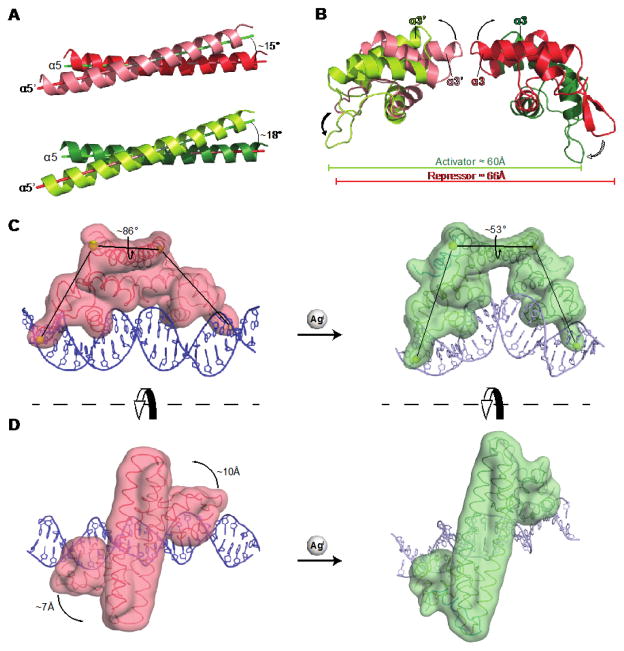

The allosteric switch starts with metal binding to stabilize the MBL conformation. This triggers displacement of key residues in the hinge between DBD and DH (Fig. 2A). The hinge residue Arg75 provides a direct allosteric link between the MBL and the DBD. The backbone carbonyl oxygen of Ala118′ of the MBL forms an H-bond with Arg75 Nε, displacing a water and flipping the residue; Nη1 now H-bonds with the backbone carbonyl oxygen atoms of Asp72 and Phe70 on α4 of the DBD (Fig. 2A). Mutation of Arg75 to alanine decreases transcription activation at PcopA in vivo, consistent with the loss of the H-bond communication network (Figs. 2C, S9A). The activator conformation is further stabilized when the CTH docks into the opened hydrophobic cavity (Fig. 2B). Hydrophobic residues Ile122, Ile123 and Leu126 project into this cavity, displacing Phe70 but not disrupting the H-bond with Arg75 (Figs. 2A, B). This locks in a new orientation between the two protomers in the activator complex. These changes shift the DHs (α5 and α5′) in a small “scissors” movement (Fig. 3A) and decrease the distance between the two DBDs by ~6 Å (Fig. 3B). Since the DBDs move as rigid domains that tightly clamp onto the DNA, their rotation (Fig. 3C) and translation (Fig. 3D) readily force the kinking and undertwisting of the intervening DNA.

Fig. 2. The Allosteric Signal Is Propagated Through the C-Terminal Loop-Helix Motif to the Hinge.

(A) Comparison of repressor (left) and activator (right) CueR depicting the transformations occurring at the CTH and hinge upon AgI binding: hinge residues R75, H76 and S77 are displaced (arrows) and form new H-bonds (dashed lines) with CTH residues. (B) The hydrophobic cavity formed by DBD and DH residues (yellow), F70 (orange) and surfaces (gray) are shown in the repressor (left). The CTH′ residues and surfaces (pink) dock into the opened hydrophobic cavity in the activator (right). (C, D, E) β-galactosidase activity for allosteric-control (AC) mutants. Error bars (under symbols) correspond to S.D. (C) The cueRR75A variant exhibits full repression in the absence of copper and diminished activation upon addition of copper. (D) The cueRCA variant exhibits greatly increased activation at all copper concentrations. (E) The cueRCR variant exhibits full repression at all copper concentrations.

Fig. 3. The DNA-Binding Domains (DBD) Rotate and Translate Upon Metal Binding.

(A) The slight “scissors” motion of the repressor (top) and activator (bottom) DHs (α5 and α5′) is shown. (B) The repressor DBDs rotate, bringing the wings closer by ~6 Å, and (C) decreasing the dihedral angle by ~33°, resulting in kinked/undertwisted DNA in the activator complex. (D) The complexes from (C) are viewed from the top. The DBDs translate by ~7 Å and ~10 Å, respectively. The DBDs move as rigid bodies: superposition of the individual repressor and the activator DBDs reveals an RMSD of ~0.5 Å for main chain atoms.

To test this mechanism, two types of allosteric-control (AC) CueR variants were made: a CuI-independent constitutive activator (CueRCA), and a constitutive repressor (CueRCR). Early phenotype screens (17, 18) and studies of A89V/S131L MerR identified variants that activate transcription in the absence of the effector, Hg II (19). We mutated homologous positions in CueR (T84V/N125L) (fig. S9B) and evaluated transcription in a cueR knock-out E. coli strain (ΔcueR) using in vivo β-galactosidase reporter assays. This variant exhibits clear CuI-independent transcription activation at all added copper concentrations (Fig. 2D), supporting its designation as a constitutive activator. To test whether the CTH communicates the allosteric signal to the DBD via docking into the hydrophobic cavity, we evaluated a mutant lacking the CTH(fig. S9C) and found it was a constitutive repressor at all copper concentrations (Fig. 2E), providing additional support for the allosteric mechanism. Inspection of other MerR-family proteins suggests that the repression and activation mechanisms, including docking of the CTH, can be employed by proteins with similar C-termini (e.g. SoxR), and by homologs with larger C-termini (e.g. BmrR). These results reveal how the allosteric transition induces significant stereochemical reorganization of the structure and orientation of the core promoter elements with little or no change in protein-DNA contacts or affinity (20, 21). To understand how these changes lead from repression to activation of transcription, we next considered the promoter geometry from the polymerase point of view.

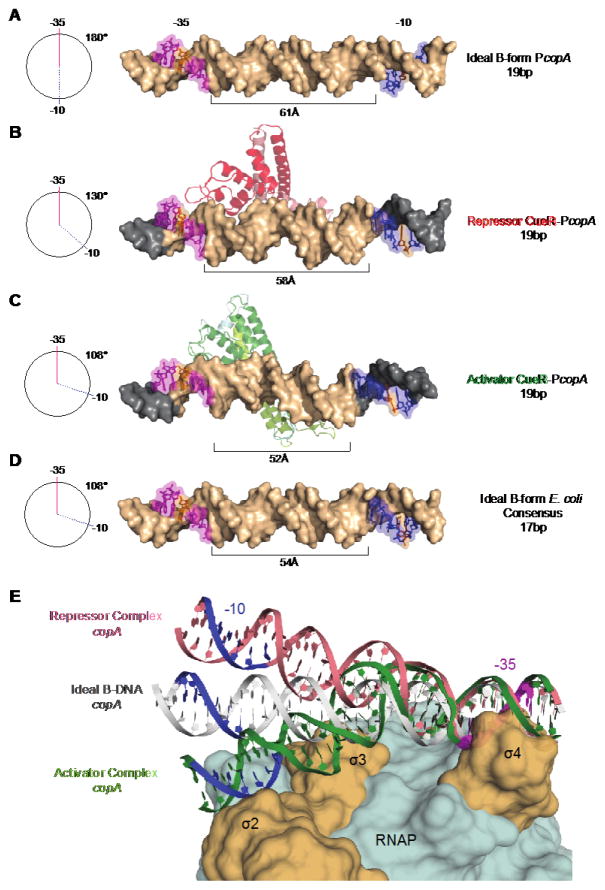

MerR family proteins are thought to work by adjusting the phase angle and distance between the hexameric polymerase contact sites, namely the −35 and −10 promoter elements (Fig. 4). In consensus E. coli promoters, there are 17 bp between these elements but in MerR-type promoters, there are 19–20 bps (22). Assuming B-form DNA, the −10 and −35 elements of the latter are 72° out of phase with respect to the productive conformation, and have a longer separation between the two polymerase binding sites (Fig. 4A). In the repressor/DNA complex, the promoter is shortened by ~3 Å (Fig. 4B), consistent with hydrodynamic and biophysical studies of apo-MerR-family/DNA complexes (20, 23, 24). The repressor also undertwists the DNA, reducing the phase angle by 50° (to ~130°), a value approaching that of a 17 bp promoter (Fig. 4B, D). Conversion to the activator structure induces further DNA undertwisting and kinking, which shortens the duplex by an additional ~6 Å relative to the repressor complex. This results in phasing and spacing parameters that are close to that of a 17 bp promoter (~108°) (Fig. 4C, D), corroborating studies of other MerR-family/DNA complexes (5, 8–10, 24). While this two-dimensional analysis provides a plausible account for transcription from the activator complex, it also suggests that the repressor, which also decreases the distance and the phase angle between the elements, should stimulate transcription. Clearly, it does not. The question of how the repressor exerts transcriptional silencing is best understood from a three-dimensional perspective.

Fig. 4. CueR Bends, Undertwists and Kinks DNA for Transcription Control.

(A) B-DNA model of PcopA (19 bp), (B) repressor CueR/DNA complex, (C) activator CueR/DNA complex, and (D) B-DNA model consensus E. coli promoter (17 bp). In (B) and (C), the crystallized DNA (tan) is extended with ideal B-DNA (gray) to include promoter elements. The radial plots (left) show relative positions of the two elements looking down the central axis with −35 in front; the corresponding angle between −10 and −35 is given. (E) DNA from the repressor and activator complexes, and the B-DNA model of PcopA were modeled onto RNAP (see fig. S10). The repressor complex DNA is bent away from σ2. The transition from repressor to activator kinks the DNA, positioning the −10 element in close proximity to σ2.

By examining how these proteins alter the overall shape of the promoter with respect to the polymerase surface, we can account for repression as well as activation. Both structures were modeled onto structurally characterized RNAP/DNA complexes (Figs. S10, 4E) (25). Consistent with results showing that MerR can form stable ternary complexes with the promoter and RNAP (7, 21), we find that CueR and RNAP can bind on opposite faces of DNA without steric penalties (figs. S10A, B). By overlaying CueR/DNA and RNAP complexes at the −35 element where the DNA interacts with the polymerase σ4 domain, we find that the repressor-imposed DNA conformation prevents contacts with the −10 element by forcing it ~40 Å away from the σ2 domain (figs. S10A, B). This is accomplished by two bends that move the DNA towards the repressor and away from the polymerase (figs. S10C). These bends map to DNaseI hypersensitivity sites in repressor MerR/DNA complexes, indicating that they persist in solution (5). We propose that this undertwisting and shortening of the promoter by the repressor poises the conformation of the DNA substrate, but maintains a significant barrier to transcription activation. As it switches from the repressor to activator, CueR introduces a major kink in the central base pairs of the promoter, bringing the −10 element to the σ2 domain. The repressor and the activator forms modulate the overall shape of the core promoter in order to place the highly critical −10 element bases (26, 27) away from or near the RNAP σ2 domain, respectively (Figs. 4E, S10B). Thus, regulatory factors can reshape a core promoter via local changes in DNA stereochemistry and thereby stimulate facile switching between inactive and active transcription states.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge NIH Grants R01GM038784 and U54CA143869, LS-CAT staff assistance at the Advanced Photon Source, a US Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility operated for DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory (Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357) and the Structural Biology Facility, Northwestern Lurie Cancer Center. Coordinates and structure factors (accession number 4WLS and 4WLW) are deposited in the Protein Data Bank.

References

- 1.Rohs R, Jin X, West SM, Joshi R, Honig B, Mann RS. Origins of specificity in protein-DNA recognition. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:233–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060408-091030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schleif R. AraC protein, regulation of the l-arabinose operon in Escherichia coli, and the light switch mechanism of AraC action. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2010;34:779–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown NL, Stoyanov JV, Kidd SP, Hobman JL. The MerR family of transcriptional regulators. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;27:145–163. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma Z, Jacobsen FE, Giedroc DP. Coordination chemistry of bacterial metal transport and sensing. Chem Rev. 2009;109:4644–4681. doi: 10.1021/cr900077w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ansari AZ, Bradner JE, O’Halloran TV. DNA-bend modulation in a repressor-to-activator switching mechanism. Nature. 1995;374:371–375. doi: 10.1038/374370a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Outten CE, Outten FW, O’Halloran TV. DNA distortion mechanism for transcriptional activation by ZntR, a Zn(II)-responsive MerR homologue in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37517–37524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.37517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frantz B, O’Halloran TV. DNA distortion accompanies transcriptional activation by the metal-responsive gene-regulatory protein MerR. Biochemistry. 1990;29:4747–4751. doi: 10.1021/bi00472a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heldwein EE, Brennan RG. Crystal structure of the transcription activator BmrR bound to DNA and a drug. Nature. 2001;409:378–382. doi: 10.1038/35053138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newberry KJ, Brennan RG. The structural mechanism for transcription activation by MerR family member multidrug transporter activation, N terminus. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20356–20362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400960200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watanabe S, Kita A, Kobayashi K, Miki K. Crystal structure of the [2Fe-2S] oxidative-stress sensor SoxR bound to DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4121–4126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709188105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Outten FW, Outten CE, Hale J, O’Halloran TV. Transcriptional activation of an Escherichia coli copper efflux regulon by the chromosomal MerR homologue, cueR. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:31024–31029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006508200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Changela A, Chen K, Xue Y, Holschen J, Outten CE, O’Halloran TV, Mondragon A. Molecular basis of metal-ion selectivity and zeptomolar sensitivity by CueR. Science. 2003;301:1383–1387. doi: 10.1126/science.1085950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stoyanov JV, Hobman JL, Brown NL. CueR (YbbI) of Escherichia coli is a MerR family regulator controlling expression of the copper exporter CopA. Molecular microbiology. 2001;39:502–511. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petersen C, Moller LB. Control of copper homeostasis in Escherichia coli by a P-type ATPase, CopA, and a MerR-like transcriptional activator, CopR. Gene. 2000;261:289–298. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00509-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamamoto K, Ishihama A. Transcriptional response of Escherichia coli to external copper. Molecular microbiology. 2005;56:215–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guzikevich-Guerstein G, Shakked Z. A novel form of the DNA double helix imposed on the TATA-box by the TATA-binding protein. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:32–37. doi: 10.1038/nsb0196-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross W, Park SJ, Summers AO. Genetic analysis of transcriptional activation and repression in the Tn21 mer operon. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:4009–4018. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.7.4009-4018.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Comess KM, Shewchuk LM, Ivanetich K, Walsh CT. Construction of a synthetic gene for the metalloregulatory protein MerR and analysis of regionally mutated proteins for transcriptional regulation. Biochemistry. 1994;33:4175–4186. doi: 10.1021/bi00180a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parkhill J, Ansari AZ, Wright JG, Brown NL, O’Halloran TV. Construction and characterization of a mercury-independent MerR activator (MerRAC): transcriptional activation in the absence of Hg(II) is accompanied by DNA distortion. EMBO J. 1993;12:413–421. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05673.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andoy NM, Sarkar SK, Wang Q, Panda D, Benitez JJ, Kalininskiy A, Chen P. Single-molecule study of metalloregulator CueR-DNA interactions using engineered Holliday junctions. Biophys J. 2009;97:844–852. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Halloran TV, Frantz B, Shin MK, Ralston DM, Wright JG. The MerR heavy metal receptor mediates positive activation in a topologically novel transcription complex. Cell. 1989;56:119–129. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90990-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Summers AO. Damage control: regulating defenses against toxic metals and metalloids. Current opinion in microbiology. 2009;12:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu C, Kim E, Demple B, Seeman NC. A DNA-based nanomechanical device used to characterize the distortion of DNA by Apo-SoxR protein. Biochemistry. 2012;51:937–943. doi: 10.1021/bi201196s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ansari AZ, Chael ML, O’Halloran TV. Allosteric underwinding of DNA is a critical step in positive control of transcription by Hg-MerR. Nature. 1992;355:87–89. doi: 10.1038/355087a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murakami KS, Masuda S, Campbell EA, Muzzin O, Darst SA. Structural basis of transcription initiation: an RNA polymerase holoenzyme-DNA complex. Science. 2002;296:1285–1290. doi: 10.1126/science.1069595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y, Feng Y, Chatterjee S, Tuske S, Ho MX, Arnold E, Ebright RH. Structural basis of transcription initiation. Science. 2012;338:1076–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1227786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feklistov A, Darst SA. Structural basis for promoter-10 element recognition by the bacterial RNA polymerase sigma subunit. Cell. 2011;147:1257–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, Keegan RM, Krissinel EB, Leslie AG, McCoy A, McNicholas SJ, Murshudov GN, Pannu NS, Potterton EA, Powell HR, Read RJ, Vagin A, Wilson KS. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2011;67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kabsch W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evans P. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:72–82. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905036693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. Journal of applied crystallography. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de La Fortelle E, Bricogne G. Maximum-Likelihood Heavy-Atom Parameter Refinement for Multiple Isomorphous Replacement and Multiwavelength Anomalous Diffraction Methods. Methods in enzymology. 1997;276:472–494. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vagin AA, Steiner RA, Lebedev AA, Potterton L, McNicholas S, Long F, Murshudov GN. REFMAC5 dictionary: organization of prior chemical knowledge and guidelines for its use. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2184–2195. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904023510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agarwal RC. A new least-squares refinement technique based on the fast Fourier transform algorithm. Acta Crystallogr A. 1978;34:791–809. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ten Eyck LF. Crystallographic fast Fourier transforms. Acta Crystallogr A. 1973;29:183–191. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen VB, Arendall WB, 3rd, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. Mol Probity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.French GS, Wilson KS. On the treatment of negative intensity observations. Acta Crystallographica A. 1978;34:517–525. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Howell PL, Smith GD. Identification of heavy-atom derivatives by normal probability methods. J Appl Cryst. 1992;25:81–86. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System Version 1.5.0.3. Shrödinger, LLC; [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu XJ, Olson WK. 3DNA: a versatile, integrated software system for the analysis, rebuilding and visualization of three-dimensional nucleic-acid structures. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1213–1227. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu XJ. 3DNA: a suite of software programs for the analysis, rebuilding and visualization of 3-Dimensional Nucleic Acid structures. 2015 http://x3dna.org/

- 44.Pettersen E, Goddard T, Huang C, Couch G, Greenblatt D, Meng E, Ferrin T. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Campbell EA, Muzzin O, Chlenov M, Sun JL, Olson CA, Weinman O, Trester-Zedlitz ML, Darst SA. Structure of the bacterial RNA polymerase promoter specificity sigma subunit. Molecular cell. 2002;9:527–539. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vassylyev DG, Sekine S, Laptenko O, Lee J, Vassylyeva MN, Borukhov S, Yokoyama S. Crystal structure of a bacterial RNA polymerase holoenzyme at 2.6 A resolution. Nature. 2002;417:712–719. doi: 10.1038/nature752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller JH. Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cornell WDC, Bayly PCI, Gould IR, Merz KM, Ferguson DM, Spellmeyer DC, Fox T, Caldwell JW, Kollman PA. Second Generation Force Field for the Simulation of Proteins A Nucleic Acids, and Organic Molecules. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:5179–5197. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cornell WD, Cieplak P, Bayly CI, Kollman PA. Application of RESP charges to calculate conformational energies, hydrogen-bond energies, and free-energies of solvation. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:9620–9631. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bayly CI, Cieplak P, Cornell WD, Kollman PA. A well-behaved electrostatic potential based method using charge restraints for deriving atomic charges - the Resp Model. J Phys Chem. 1993;97:10269–10280. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cieplak PC, Bayly WDC, Kollman PA. Application of the multimolecule, multiconformational RESP methodology to biopolymers: Charge derivation for DNA, RNA, and proteins. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 1995;16:1357–1377. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peterson KA, Puzzarini C. Systematically convergent basis sets for transition metals. Pseudopotential-based correlation consistent basis sets for the group 11 (Cu II Ag Au) 12 (Zn Cd, Hg) elements. Theor Chem Acc. 2005;114:283–296. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmidt MW, Baldridge KK, Boatz JA, Elbert ST, Gordon MS, Jensen JH, Koseki S, Matsunaga N, Nguyen KA, Su SJ, Windus TL, Dupuis M, Montgomery JA. General atomic and molecular electronic-structure system. J Comput Chem. 1993;14:1347–1363. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Joung IS, Cheatham TE., 3rd Determination of alkali and halide monovalent ion parameters for use in explicitly solvated biomolecular simulations. The journal of physical chemistry. B. 2008;112:9020–9041. doi: 10.1021/jp8001614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jorgensen WLC, Madura JJD, Impey RW, Klein ML. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yildirim IS, Kennedy HA, Tubbs SD, Turner JDDH. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2010;6:1520–1531. doi: 10.1021/ct900604a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Perez A, Marchan I, Svozil D, Sponer J, Cheatham TE, 3rd, Laughton CA, Orozco M. Refinement of the AMBER force field for nucleic acids: improving the description of alpha/gamma conformers. Biophys J. 2007;92:3817–3829. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.097782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yildirim I, Kennedy SD, Stern HA, Hart JM, Kierzek R, Turner DH. Revision of AMBER Torsional Parameters for RNA Improves Free Energy Predictions for Tetramer Duplexes with GC and iGiC Base Pairs. J Chem Theory Comput. 2012;8:172–181. doi: 10.1021/ct200557r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yildirim I, Stern HA, Tubbs JD, Kennedy SD, Turner DH. Benchmarking AMBER force fields for RNA: comparisons to NMR spectra for single-stranded r(GACC) are improved by revised chi torsions. The journal of physical chemistry. B. 2011;115:9261–9270. doi: 10.1021/jp2016006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ryckaert JPC, Berendsen GHJC. Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. Journal of Computational Physics. 1977;23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 61.DAD, Case TA, Cheatham TEI, Simmerling CL, Wang J, Duke RE, Luo R, Walker RC, Zhang W, Merz KM, Roberts B, Wang B, Hayik S, Roitberg A, Seabra G, Kolossváry I, Wong KF, Paesani F, Vanicek J, Liu J, Wu X, Brozell SR, Steinbrecher T, Gohlke H, Cai Q, Ye X, Wang J, Hsieh M-J, Cui G, Roe DR, Mathews DH, Seetin MG, Sagui C, Babin V, Luchko T, Gusarov S, Kovalenko A, Kollman PA. AMBER 11. University of California; San Fransisco: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kumaraswami M, Newberry KJ, Brennan RG. Conformational plasticity of the coiled-coil domain of BmrR is required for bmr operator binding: the structure of unliganded BmrR. J Mol Biol. 2010;398:264–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim Y, Geiger JH, Hahn S, Sigler PB. Crystal structure of a yeast TBP/TATA-box complex. Nature. 1993;365:512–520. doi: 10.1038/365512a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lu XJ, Olson WK. 3DNA: a software package for the analysis, rebuilding and visualization of three-dimensional nucleic acid structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5108–5121. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lu XJ, Shakked Z, Olson WK. A-form conformational motifs in ligand-bound DNA structures. J Mol Biol. 2000;300:819–840. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Frederick CA, Quigley GJ, Teng MK, Coll M, Van der Marel GA, Van Boom JH, Rich A, Wang AH. Molecular structure of an A-DNA decamer d(ACCGGCCGGT) Eur J Biochem. 1989;181:295–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb14724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mazur AK. Electrostatic Polymer Condensation and the A/B Polymorphism in DNA: Sequence Effects. J Chem Theory Comput. 2005;1:325–336. doi: 10.1021/ct049926d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, Lopez R, McWilliam H, Remmert M, Soding J, Thompson JD, Higgins DG. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Molecular systems biology. 2011;7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Humbert MV, Rasia RM, Checa SK, Soncini FC. Protein signatures that promote operator selectivity among paralog MerR monovalent metal ion regulators. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:20510–20519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.452797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.