Abstract

Objective

This study examined negative and positive affect in relation to restrictive eating episodes (i.e., meals/snacks perceived as restrictive) and whether restrictive eating was associated with likelihood of subsequent eating disorder behaviors (i.e., additional restrictive eating, binge eating, vomiting, laxative use, weighing, exercising, meal skipping, drinking fluids to curb appetite, body checking).

Method

Women with anorexia nervosa (N = 118) completed a two-week ecological momentary assessment protocol.

Results

For both restrictive and non-restrictive eating, negative affect significantly increased from pre-behavior to the time of the behavior but remained stable thereafter, while positive affect remained stable from pre-behavior to the time of the behavior but decreased significantly thereafter. Across time, negative affect was significantly lower and positive affect was significantly greater in restrictive than non-restrictive episodes. Engagement in restrictive eating was associated with an increased likelihood of subsequent restrictive eating, laxative use, and body checking, but not other behaviors. Engagement in non-restrictive eating was associated with a decreased likelihood of subsequent restrictive eating, binge eating, vomiting, laxative use, weighing, meal skipping, drinking fluids to curb appetite, and body checking.

Discussion

Despite similar patterns of affect across eating episodes over time, results suggest affect may be involved in the maintenance of restrictive eating in anorexia nervosa since restrictive episodes were associated with lower negative and greater positive affect across time compared to non-restrictive episodes. Further, while restrictive episodes increased the likelihood of only three subsequent eating disorder behaviors, non-restrictive episodes were protective since they decreased likelihood of all but one behavior.

Keywords: anorexia nervosa, ecological momentary assessment, negative affect, positive affect, restrictive eating

Various theoretical models of eating pathology suggest that eating disorder behaviors regulate affect.1-6 In the case of anorexia nervosa (AN), Fairburn, Shafran, and Cooper7 highlighted the role of dietary restriction (defined as “true undereating in a physiological sense” that results in weight loss, Ref. 8, p. 11) in decreasing and avoiding negative emotions as well as increasing positive emotions. Within this cognitive-behavioral model, the negative and positive reinforcement that results from dietary restriction in AN may in turn be associated with further food restriction and engagement in other eating disorder behaviors, such that engagement in restriction may result in a downward or “anorexic spiral.”9

Despite the fact that severely restricted dietary intake is a defining feature of AN,10 very little research has examined the actual maintenance and consequences of dietary restriction in this population. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA), which involves assessing participants multiple times per day in their natural environments (see Ref. 11 for an overview of this approach), is particularly well suited to exploring these research questions. Using EMA, our research group found that higher negative affect on a given day was associated with an increased likelihood of dietary restriction (defined as either not eating for eight continuous hours or consuming <1,200 kcal for the day) on the following day, and conversely that higher momentary positive affect on a given day was associated with a decreased likelihood of dietary restriction on the following day among women with AN.12 However, affect (both positive and negative) on the day after dietary restriction was not significantly different from affect on days after non-restriction.12 This study thus provided information on individuals’ affect on the days prior to and following a dietary restriction “day” but did not provide any information on: 1) whether affect is an immediate antecedent to specific episodes of restrictive eating, or what happens to affect following engagement in specific episodes of restrictive eating; or 2) the short-term consequences of restrictive eating—whether restrictive eating spurs additional eating disorder behaviors within the same day.

Indeed, research has not yet examined negative and positive affect prior to and following specific episodes of restrictive eating (i.e., meals or snacks that the individual perceives as being restrictive) or whether specific episodes of restrictive eating initiate a downward spiral with respect to further eating disorder symptoms. Examining restrictive eating in this way (i.e., specific episodes versus only dietary restriction “days”) may be important because less than three quarters of the Engel et al.12 (and current) sample reported any dietary restriction “days” (defined as either not eating for eight continuous hours or consuming less than 1,200 kcal for the day), and only about one third of days were even characterized by dietary restriction. These data suggest that self-reported dietary restriction “days” are not ubiquitous among women with AN. As such, in the context of AN, there may be limitations to Fairburn’s8 definition of dietary restriction, which focuses more on the trait-like component of this behavior. In addition to understanding sustained under-eating, it may also be valuable to better understand momentary “restriction” as it is defined by individuals with AN. Likewise, restricted dietary intake in AN has been conceptualized as a series of “choices,” with the word “choice” being used to convey that AN is characterized by an individual’s persistent, active selection of a restrictive diet and not that AN itself is a choice.13 Therefore, exploring discrete episodes of restrictive eating may be a complementary way to examine the construct of restriction as it is often engaged in among individuals with AN and may help to provide a more nuanced and complete understanding of the maintenance and consequences of restrictive eating within the cognitive-behavioral model.

The case for examining discrete episodes of restrictive eating in AN, which may or may not occur in the context of restriction “days,” is akin to the case for examining discrete episodes of binge eating in bulimia nervosa (BN) (as opposed to binge eating days versus non-binge eating days). In BN, binge days are associated with less positive affect and higher negative affect; in contrast, specific binge eating episodes are preceded by decreasing positive affect and increasing negative affect and are followed by increasing positive affect and decreasing negative affect.14 Without examining trajectories of affect surrounding specific binge eating episodes, it may have been thought that binge eating led to less positive and more negative affect, when in fact the exact opposite was found when those trajectories were examined. Likewise, the examination of affect surrounding specific episodes of restrictive eating may shed light on the role of affect in the maintenance of more momentary engagement in this behavior and provide information that cannot be obtained from an examination of affect on restriction versus non-restriction days. Furthermore, directly examining whether restrictive eating initiates a downward spiral with respect to further eating disorder symptoms may help to identify additional maintenance mechanisms of AN. Such information would have significant clinical implications that might help to guide treatment efforts.

The purpose of the current study was to expand on the findings of Engel et al.12 by examining momentary negative and positive affect in relation to restrictive meals and snacks (as opposed to dietary restriction “days”) using EMA. The present study also examined whether engagement in restrictive eating was associated with an increased likelihood of subsequent eating disorder behaviors (i.e., additional restrictive eating, binge eating, vomiting, laxative use, weighing, exercising, meal skipping, drinking fluids to curb appetite, body checking), controlling for engagement in those eating disorder behaviors at the time of restrictive eating. Given the dearth of research on affect in relation to discrete episodes of restrictive eating, no specific hypotheses were made and these analyses should be considered exploratory. We hypothesized that engagement in a restrictive eating episode would be associated with an increased likelihood of subsequent eating disorder behaviors. As has been suggested to be at work in other forms of psychopathology (e.g., depression, anxiety),15 we believe that restrictive eating may initiate a downward spiral whereby one disordered behavior engenders another, potentially resulting in a self-perpetuating and damaging cycle.

Method

Participants

Participants were women (N = 118) meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV)16 criteria for full (n = 59) or subthreshold AN (n = 59), determined using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P).17 Subthreshold AN was defined as meeting all DSM-IV criteria for AN except 1) body mass index (BMI) could be 17.6-18.5 kg/m2 or 2) either amenorrhea or the cognitive symptoms (i.e., body image disturbance and intense fear of fat) of AN could be absent. In total, 121 individuals met inclusion criteria (i.e., being female, at least 18 years, full or subthreshold AN), agreed to participate, and were enrolled. Three participants with EMA compliance rates of less than 50% were excluded from analyses, leaving a total of 118 participants. Most participants were Caucasian (96.6%), single/never married (75.4%), and had completed at least some post-secondary education (90.7%). With regard to AN subtype, 45 (38.1%) participants were classified as meeting criteria for the binge eating/purging subtype and 73 (61.9%) were classified as meeting criteria for the restricting subtype. Participants had a mean BMI of 17.2 kg/m2 (SD = 1.0; range = 13.4-18.5 kg/m2) and a mean age of 25.3 years (SD = 8.4; range = 18-58 years).

Procedure

Participants were recruited at three sites (Fargo; Minneapolis; Chicago) from various clinical and community sources. After completing an initial phone screen and attending an informational meeting where written informed consent was obtained, participants were scheduled for two assessment visits. Participants were assessed for medical stability and completed self-report questionnaires and structured interviews during these visits. This study was approved by the institutional review board at each site.

During the first assessment visit, research personnel provided training on how to use the palmtop computer for the EMA protocol. Participants provided data for two practice days (not used in the analyses) to establish familiarity with the EMA protocol and minimize reactivity (although past research suggests little evidence of this18). Participants were then given the palmtop computer to complete EMA recordings over the subsequent two weeks, during which attempts were made to schedule each participant for 2-3 visits to obtain recorded data (to minimize loss in the event of technical problems) and to provide compliance feedback. Participants were compensated $100 per week of EMA and were given a $50 bonus for a compliance rate of at least 80% responding to random signals.

The EMA protocol used three types of data collection methods: signal-contingent, event-contingent, and interval-contingent.19 Each EMA report took 2-3 minutes to complete. Participants provided signal-contingent data at six semi-random times throughout the day (every 2-3 hours between 8:00 am and 10:00 pm). When signaled, participants were asked to rate their current mood and to report any eating episode or eating disorder behavior that occurred after the last signal but that had not yet been reported. Participants were also asked to provide event-contingent data when any eating episodes (regular or binge) or eating disorder behaviors occurred and interval-contingent data by completing EMA ratings of mood and other constructs at the end of each day (e.g., whether they had limited daily intake to <1,200 kcal).

EMA Measures

Positive and negative affect

An abbreviated version of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS)20 was used to assess momentary affect. Items included eight assessing negative affect (i.e., nervous, disgusted, distressed, ashamed, angry at self, afraid, sad, dissatisfied with self) and eight assessing positive affect (i.e., strong, enthusiastic, proud, attentive, happy, energetic, confident, cheerful). Participants were asked to rate their current mood on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). In the current study, alpha was .92 for positive affect and .94 for negative affect.

Restrictive and non-restrictive eating episodes

Participants were asked to report all eating episodes, indicating whether the episode was a meal, snack, or binge. Participants then rated each eating episode on several features. Restrictive eating episodes were defined as meals/snacks for which the participant indicated that she “ate as little as possible” and did not endorse that she “ate an excessive amount of food.” The participant may have also indicated that she “limited calories,” “limited fat grams,” and/or “limited carbs” but these were not essential in defining the episode as restrictive. This operational definition was chosen given that it was significantly more strongly correlated with participants’ end of day ratings of limiting intake to <1,200 kcal (r = .31, p < .001) than a definition using all four indicators (i.e., ate as little as possible, limited calories, limited fat grams, and/or limited carbs) (r = .17, Z = 5.63, p < .001) or two indicators (i.e., ate as little as possible and/or limited calories) (r = .22, Z = 3.56, p < .001).21 Meals and snacks that were not defined as restrictive were classified as non-restrictive. Of note, the current definition for a restrictive eating episode (i.e., “ate as little as possible” but not “ate an excessive amount of food”) is similar to that used in a recent EMA study of college women with subclinical disordered eating (i.e., “Did you try to limit the amount of food you ate?”),22 providing support for the validity of this approach for assessing restrictive eating episodes.

Eating disorder behaviors

Participants were asked to report engagement in eating disorder behaviors, including self-induced vomiting, laxative use for weight control, weighing one’s self on a scale, exercising, meal skipping, drinking fluids to curb appetite, body checking (i.e., “I made sure my thighs didn’t touch” and/or “I checked my joints and bones for fat”), and binge eating. The EMA measure of binge eating was defined as a participant endorsing the “binge” option regarding her eating episode. This rating could be indicated when recording an eating episode or during a random signal in which the participant indicated that she had engaged in binge eating since the last signal. Binge eating was defined for participants as both: 1) eating an unambiguously large amount of food (“an amount of food that most people would consider excessive”) and 2) experiencing a sense of loss of control over eating (“the inability to stop eating”).

Statistical Analyses

Multilevel modeling was used to examine negative and positive affect in relation to both restrictive and non-restrictive eating episodes. In particular, we examined models with time, eating episode type (i.e., restrictive versus non-restrictive), and their interaction as predictors of affect; these models included a random intercept. Time was coded relative to the eating episode (i.e., mood pre-episode, at the time the episode was reported, and post-episode). These models assume that repeated observations are nested within persons. If two eating episodes were recorded at two back-to-back signals, the first episode would not have post-episode affect ratings and the second episode would not have pre-episode affect ratings. That is, we did not use affect ratings two times/in two different ways, and data points that would have been used twice were dropped.

Generalized estimating equation (GEE)23 models with a logit response function were used to assess eating episode type (restrictive versus non-restrictive, both relative to not engaging in an eating episode) as a predictor of engagement in a restrictive eating episode and other eating disorder behaviors at the next report, controlling for engagement in that same eating disorder behavior at the prior report. Only within-day lagged effects were examined. That is, eating episode type before going to sleep one evening was not examined as a predictor of eating disorder behaviors the next morning.

In order to provide an even more stringent test of the study hypotheses, analyses were re-run controlling for BMI, AN subtype, and full/subthreshold AN. Results were the same whether or not these covariates were included, with three minor exceptions noted in the Results. As such, results without covariates included are presented for the sake of parsimony.

Results

Participants provided 14,945 separate EMA recordings, representing 1,768 separate participant days. These recordings included 9,085 responses to signals, 3,383 eating episode recordings, 999 eating disorder behavior recordings, and 1,478 end-of-day recordings. Compliance rates to signals (defined as responding to signals within 45 minutes) averaged 87% across participants (range = 58-100%). Compliance with end-of-day ratings averaged 89% (range = 24-100%).

Participants reported an average of 11.68 restrictive eating episodes (SD = 12.81; range = 0-63) and 32.14 non-restrictive eating episodes (SD = 21.52; range = 1-90) over the two-week EMA period, for an average of 3.13 eating episodes per day. One or more restrictive eating episodes were reported by 83.1% of participants, and one or more non-restrictive eating episodes were reported by 100.0% of participants. Over the two-week interval, participants reported an average of 2.52 binge eating episodes (SD = 4.90; range = 0-30), 4.26 vomiting episodes (SD = 8.89; range = 0-43), .62 episodes of laxative use (SD = 1.83; range = 0-13), 4.98 episodes of weighing (SD = 7.17; range = 0-46), 6.28 exercise episodes (SD = 7.89; range = 0-45), 6.98 episodes of meal skipping (SD = 8.01; range = 0-34), 10.42 episodes of drinking fluids to curb their appetite (SD = 12.34; range = 0-58), and 23.58 instances of body checking (SD = 26.72; range = 0-88). Binge eating episodes were reported by 42.4% of participants, vomiting by 39.8%, laxative use by 21.2%, weighing by 62.7%, exercise by 72.0%, meal skipping by 78.0%, drinking fluids to curb appetite by 79.7%, and body checking by 71.2%.

Affect in Relation to Restrictive and Non-Restrictive Eating Episodes

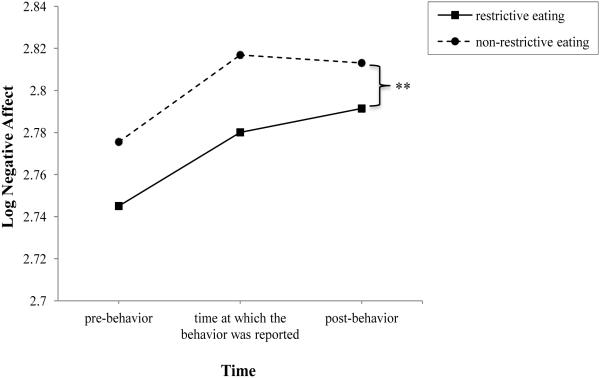

Negative affect

Results indicated that negative affect was non-normally distributed (standardized skew = 16.64); as such, log transformed values were used in the multilevel regression model. Results indicated that both time (F(2, 8541.04) = 14.50, p < .001) and eating episode type (F(1, 8596.95) = 9.92, p < .002) significantly predicted negative affect, while their interaction did not (F(2, 8540.34) = .16, p < .86). As depicted in Figure 1, across eating episode type, negative affect significantly increased from pre-behavior to the time the behavior was reported (p < .001), as well as from pre-behavior to post-behavior (p < .001). However, negative affect was not significantly different from the time the behavior was reported to post-behavior (p < .81). Results also indicated that across time (i.e., pre-episode, at the time the episode was reported, and post-episode), negative affect was significantly greater overall in non-restrictive than in restrictive eating episodes (p < .002). The non-significant time by eating episode type interaction suggests that on average, trajectories of negative affect from pre-behavior to post-behavior did not significantly differ between restrictive and non-restrictive eating episodes.

Figure 1. Level of negative affect over time in relation to restrictive and non-restrictive eating episodes.

Note. ** indicates that across time, negative affect was significantly greater overall in non-restrictive than in restrictive eating episodes (p < .002).

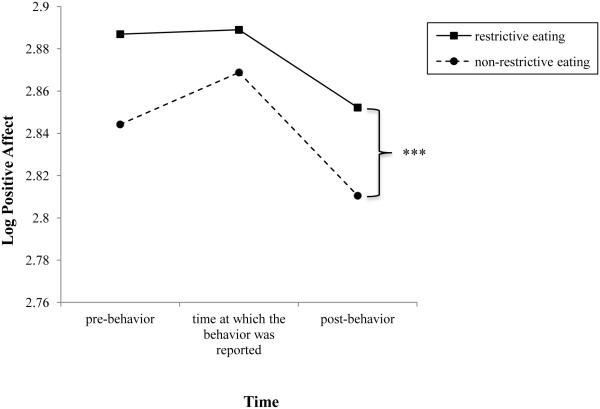

Positive Affect

Similar to negative affect, log transformed values for positive affect were used in the multilevel regression model due to its non-normal distribution (standardized skew = −6.60). Results indicated that both time (F(2, 8542.49) = 9.18, p < .001) and eating episode type (F(1, 8619.62) = 23.13, p < .001) significantly predicted positive affect, while their interaction did not (F(2, 8541.44) = .45, p < .64). As depicted in Figure 2, across eating episode type, positive affect significantly decreased from the time the behavior was reported to post-behavior (p = .001), as well as from pre-behavior to post-behavior (p < .001). However, positive affect did not change significantly from pre-behavior to the time the behavior was reported (p < .16). Results also indicated that across time (i.e., pre-episode, at the time the episode was reported, and post-episode), positive affect was significantly greater overall in restrictive than in non-restrictive eating episodes (p < .001). The non-significant time by eating episode type interaction suggests that on average, trajectories of positive affect from pre-behavior to post-behavior did not significantly differ between restrictive and non-restrictive eating episodes.

Figure 2. Level of positive affect over time in relation to restrictive and non-restrictive eating episodes.

Note. *** indicates that across time, positive affect was significantly greater overall in restrictive than in non-restrictive eating episodes (p < .001).

Of note, for both restrictive and non-restrictive eating episodes, the average time interval between affect ratings made pre-episode and at the time of the episode (restrictive: 121.64 minutes, SD = 83.22, range = 5-761; non-restrictive: 120.80 minutes, SD = 71.30, range = 5-640) was larger than the average interval between affect ratings made at the time of the episode and post-episode (restrictive: 84.17 minutes, SD = 70.17, range = 1-426; non-restrictive: 67.74 minutes, SD = 69.97, range = 1-733) (restrictive: d = .49; non-restrictive: d = .75).

Eating Episode Type as a Predictor of Later Engagement in Additional Eating Disorder Behaviors

Engagement in a restrictive eating episode was significantly associated with an increased likelihood of subsequent engagement in another restrictive eating episode at the next report, relative to engagement in a non-restrictive eating episode (B = 1.07, odds ratio (OR) = 2.91, Wald χ2 = 28.22, p < .001). Engagement in a non-restrictive eating episode was significantly associated with a decreased likelihood of subsequent engagement in a restrictive eating episode, relative to engagement in a non-restrictive eating episode (B = −1.27, OR = .28, Wald χ2 = 50.37, p < .001).

Results of the analyses examining eating episode type as a predictor of engagement in other eating disorder behaviors at the next report, controlling for engagement in that same eating disorder behavior at the prior report, are presented in Table 1. Engagement in a restrictive eating episode was significantly associated with an increased likelihood of subsequent laxative use (OR = 2.90, p < .02) and body checking (OR = 2.36, p < .001) and a decreased likelihood of subsequent weighing (OR = .71, p < .03). Engagement in a restrictive eating episode was not significantly associated with later engagement in any other eating disorder behaviors (ps > .094). Engagement in a non-restrictive eating episode was significantly associated with a decreased likelihood of subsequent binge eating (OR = .51, p < .004), vomiting (OR = .49, p < .001), laxative use (OR = .31, p < .006), weighing (OR = .42, p < .001), meal skipping (OR = .25, p < .001), drinking fluids to curb appetite (OR = .53, p < .001), and body checking (OR = .77, p < .03). When controlling for covariates, engagement in a non-restrictive eating episode was not significantly associated with likelihood of subsequent body checking (p < .09). Engagement in a non-restrictive eating episode was not significantly associated with likelihood of subsequent exercise (p < .41). Of note, engagement in a particular eating disorder behavior was always significantly associated with an increased likelihood of subsequent engagement in that same behavior (ps < .002), with the exception that when controlling for covariates, engagement in binge eating and vomiting were not significantly associated with likelihood of subsequent engagement in these behaviors (ps > .13).

Table 1.

Parameter Estimates for Generalized Estimating Equation Models Examining Eating Episode Type as a Predictor of Later Engagement in Eating Disorder Behaviors

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variables | B | SE | Odds Ratio | Wald χ2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binge eatingT2 | Restrictive eating episodeT1 | −.30 | .27 | .74 | 1.19 | .28 |

| Non-restrictive eating episode T1 | −.69 | .24 | .51 | 8.39 | .004 | |

| Binge eating T1 | 1.16 | .32 | 3.19 | 13.06 | < .001 | |

|

| ||||||

| VomitingT2 | Restrictive eating episodeT1 | −.10 | .25 | .91 | .15 | .70 |

| Non-restrictive eating episode T1 | −.72 | .19 | .49 | 13.86 | < .001 | |

| Vomiting T1 | 1.28 | .23 | 3.60 | 30.65 | < .001 | |

|

| ||||||

| Laxative use T2 | Restrictive eating episodeT1 | 1.06 | .46 | 2.90 | 5.46 | .02 |

| Non-restrictive eating episode T1 | −1.17 | .43 | .31 | 7.43 | .006 | |

| Laxative use T1 | 2.97 | .46 | 19.39 | 40.68 | < .001 | |

|

| ||||||

| WeighingT2 | Restrictive eating episodeT1 | −.35 | .16 | .71 | 4.60 | .03 |

| Non-restrictive eating episode T1 | −.87 | .21 | .42 | 17.59 | < .001 | |

| Weighing T1 | 1.12 | .29 | 3.06 | 14.83 | < .001 | |

|

| ||||||

| ExerciseT2 | Restrictive eating episodeT1 | .28 | .17 | 1.33 | 2.78 | .10 |

| Non-restrictive eating episode T1 | .09 | .11 | 1.10 | .67 | .41 | |

| Exercise T1 | .77 | .23 | 2.15 | 10.71 | .001 | |

|

| ||||||

| Skip mealT2 | Restrictive eating episodeT1 | −.40 | .24 | .67 | 2.69 | .10 |

| Non-restrictive eating episode T1 | −1.39 | .17 | .25 | 65.24 | < .001 | |

| Skip meal T1 | .71 | .20 | 2.03 | 12.89 | < .001 | |

|

| ||||||

| Drinking fluidsT2 | Restrictive eating episodeT1 | .18 | .15 | 1.20 | 1.45 | .23 |

| Non-restrictive eating episode T1 | −.64 | .15 | .53 | 17.20 | < .001 | |

| Drinking fluids T1 | 1.29 | .15 | 3.65 | 79.66 | < .001 | |

|

| ||||||

| Body checkingT2 | Restrictive eating episodeT1 | .86 | .14 | 2.36 | 35.64 | < .001 |

| Non-restrictive eating episode T1 | −.26 | .12 | .77 | 4.56 | .03 | |

| Body checking T1 | 1.49 | .18 | 4.44 | 70.24 | < .001 | |

Note. T1 = Time 1. T2 = Time 2. These terms are meant to refer to the notion that we examined the relationships between the independent variables at one EMA report and the dependent variable at the next EMA report.

Discussion

The current study examined negative and positive affect in relation to engagement in discrete episodes of restrictive eating among women with AN using EMA. This investigation extends upon previous work examining affect in relation to dietary restriction “days”12 by examining restrictive eating episodes. We also examined whether engagement in a restrictive eating episode was prospectively associated with an increased likelihood of engagement in additional eating disorder behaviors.

Some past research suggested that higher momentary negative affect on a given day was associated with a greater likelihood of dietary restriction the next day and that higher momentary positive affect on a given day was associated with a decreased likelihood of dietary restriction the next day among women with AN, but the reciprocal relationships were not found—restriction one day did not predict negative or positive affect the next day.12 However, the extent to which these findings would extend to discrete episodes of restrictive eating was unclear. Examining affect in relation to discrete episodes of restrictive eating is essential given that self-reported dietary restriction “days” are not ubiquitous among women with AN12 and that such an examination may shed light on the maintenance of restrictive eating on a more momentary, within-day level and allow for further testing of the cognitive-behavioral theory. While negative affect did indeed significantly increase prior to restrictive eating episodes, it remained stable following the behavior. Positive affect showed no change prior to restrictive eating and actually significantly decreased following the behavior. The pattern of affect was similar for non-restrictive eating episodes. One interpretation of the current findings is that any kind of eating (restrictive or non-restrictive) may be negatively anticipated by individuals with AN and result in decreased positive affect. However, restrictive eating episodes were associated with lower negative affect and greater positive affect across time compared to non-restrictive episodes. This finding suggests that affect may be involved in the maintenance of restrictive eating episodes overall, in the sense that mood appeared to be better before, during, and after engaging in restrictive versus non-restrictive eating; however, actual engagement in restrictive eating does not appear to improve mood.

Although individuals may not consciously restrict to feel “less bad,” as just discussed, restrictive episodes are associated with better mood than non-restrictive episodes. In Dignon et al.’s9 patient testimonies, individuals with AN reported that exerting control over food provides considerable enjoyment (e.g., “feeling that I’m good at something,” “I’m onto a good thing here,” p. 950). Although the data do not support this directly, they do suggest that restricting is associated with less bad feelings and more positive feelings overall—feelings that may stick with those with AN when they think back on restricting.

A number of factors should be considered in interpreting these findings. First, we examined affect in relation to self-reported restrictive eating episodes—episodes for which participants endorsed that they “ate as little as possible.” Some research suggests that dietary restraint and actual caloric restriction may not be highly related.10,24 Thus, it is possible that the meals/snacks that participants in the current study identified as restrictive were not actually calorically restrictive. Nevertheless, participants may indeed have been restricting their intake relative to what they would have liked to have eaten at the time,25 which in and of itself may have negative consequences (e.g., increased eating disorder behaviors).26 In addition, this assessment approach is very similar to that used in a recent EMA study of college women with subclinical disordered eating for assessing restrictive eating (i.e., “Did you try to limit the amount of food you ate?”), providing additional support for its utility.22

Second, it is possible that the uneven timing of affect ratings may have influenced results. For example, although negative affect was found to be significantly greater post- versus pre-restrictive eating, post-episode affect ratings occurred more proximally to the restrictive eating episode than pre-episode affect ratings. As postulated by Berg et al.,27 negative affect could have been on the decline and may have ultimately ended up lower post- versus pre-restrictive eating episode, but this pattern may have not been captured due to the uneven timing of affect ratings. Third, because episodes of restrictive eating (as defined here) occurred rather frequently, we were only able to examine affect ratings prior to, at, and following the episode (i.e., three data points total). Future research may benefit from examining longer trajectories of affect prior to and following episodes of restrictive eating, with more frequent measurement of affect across this extended time, as past research has indicated that comparing proximal affect ratings before and after eating disorder behaviors versus examining longer trajectories of affect can result in different patterns of findings.12 It is possible that the affective effects of restrictive eating are immediate and briefly experienced, and as such, more frequent assessment of affect following restrictive eating may be especially important.

Regardless, these findings may have implications for the cognitive-behavioral theory of AN. As previously discussed, this theory suggests that dietary restriction functions to decrease negative emotions and increase positive emotions,7 and studies regarding the neurobiology of AN have provided some support for this model (e.g., palatable food ingestion associated with striatal endogenous dopamine release, which is associated with anxiety in those recovered from AN28). Neither Engel et al.12 nor the present study found support for decreased negative emotions or increased positive emotions following a dietary restriction day or a discrete restrictive eating episode, respectively. However, the current study did find that restrictive eating episodes were associated with lower negative and greater positive affect across time than non-restrictive eating episodes. Future research should confirm whether dietary restriction and restrictive eating are negatively and positively reinforced in the shorter-term or rather whether restrictive eating is more generally associated with less negative and more positive affect than non-restrictive eating. Alternatively, it may be necessary to examine more specific emotions (e.g., anxiety), rather than composite negative and positive emotionality constructs, in relation to restrictive eating. If other studies, using even stronger methodological approaches for assessing restrictive eating and examining specific emotions, confirm that restrictive eating among those with AN is not negatively and positively reinforced in the shorter-term, theories of AN maintenance may need to be modified.

Results also revealed that engagement in restrictive eating was associated with an increased likelihood of subsequent restrictive eating, laxative use, and body checking. These results are somewhat consistent with the hypothesis that engagement in a restrictive eating episode would potentially precipitate a downward spiral in terms of exacerbating eating disorder symptoms. Surprisingly, however, restrictive eating was not predictive of engagement in other types of eating disorder behaviors. In fact, engagement in a restrictive eating episode was associated with a decreased likelihood of subsequent weighing. It is possible that restrictive eating immediately enhances an individual’s sense of being in control,7 which decreases the urge to engage in most other eating disorder behaviors. Future research should test the effect of restrictive eating on momentary feelings of control and the role of such feelings in the prediction of subsequent eating disorder behaviors. Nevertheless, engagement in non-restrictive eating was associated with a decreased likelihood of subsequent restrictive eating, binge eating, vomiting, laxative use, weighing, meal skipping, drinking fluids to curb appetite, and body checking. Thus, while restrictive eating episodes did not always increase the likelihood of later eating disorder behaviors, non-restrictive eating appeared to be protective against later engagement in such behaviors. Just as clusters of negative behaviors, such as restrictive eating, binge eating, and substance use, may occur in a downward spiral, clusters of more positive, healthful behaviors may occur and work together in an upward spiral.29,30

Of particular interest is the fact that restrictive eating episodes tend to be followed by more restrictive eating but that non-restrictive eating episodes are associated with a decreased likelihood of subsequent restrictive eating. It is possible that restrictive eating leaves individuals feeling less full or satiated, and thus, they may feel compelled to “eat as little as possible” again sooner (i.e., at the next time point) than would be the case following a non-restrictive eating episode—these behaviors could function in a vicious cycle. In contrast, non-restrictive eating may leave individuals feeling more appropriately full, thus making it less likely that they would feel compelled to eat again very soon. As aforementioned, non-restrictive eating may also promote upward spirals of more healthful behaviors.

A major strength of the current study is its use of EMA given that this approach reduces the impact of retrospective recall bias.11 Additional strengths include the use of a relatively large sample of individuals with AN and the examination of affect surrounding and the momentary effects of restrictive eating, understudied research areas in AN. Although we are unaware of any other research on affect surrounding or the consequences of discrete episodes of restrictive eating in AN, this study nonetheless is limited by reliance on self-reported dietary intake, which may have resulted in potentially under- or over-reporting. Given that all of the participants in the current study were at a low body weight, it is possible that they may not have a realistic notion of whether or not a given episode is restrictive. Additionally, although the current methodological approach has a number of strengths, EMA data are still subject to some of the issues inherent to self-report assessment.31 Finally, it is important to consider that non-restrictive eating episodes (defined as any meal/snack for which the individual did not endorse “eating as little as possible”) may or may not be particularly informative in the context of an overall pattern of dietary restriction as seen in AN. However, findings suggest that it may be informative to examine non-restrictive eating episodes—even within the context of restrictive eating patterns in AN—since non-restrictive eating episodes were associated with a decreased likelihood of nearly all eating disorder behaviors examined.

Future research should replicate this study using objective measures of restrictive eating episodes based on caloric and other metrics of energy intake. It may also be of use to examine trajectories of affect and consequences of meal skipping. However, the fact that meal skipping behavior tends to be less discrete limits our ability to precisely locate this behavior in temporal space and accurately examine trajectories of affect prior to and following its occurrence. Additionally, it may be of interest for future research to examine the effects of experimental affect manipulation on discrete eating episodes in order to further ascertain how pre-eating affect impacts the type of subsequent eating episode.

Results of the current study have several clinical implications. Given that engagement in discrete episodes of restrictive eating was associated with decreases in positive affect and no change in negative affect, it may be useful for treatment to target patients’ expectations regarding the impact of restrictive eating on mood. In addition, it may also be useful to explicitly discuss the finding that engagement in restrictive eating may initiate a downward spiral with respect to eating disorder symptoms, whereas engagement in non-restrictive eating episodes may prevent subsequent eating disorder behaviors from occurring. Of particular interest is the fact that restrictive eating tended to be followed by more restrictive eating episodes, whereas non-restrictive eating was followed by fewer restrictive eating episodes. These findings suggest that focusing on restrictive behavior—decreasing restrictive and increasing non-restrictive eating episodes—may be therapeutically productive in terms of ultimately decreasing engagement in dietary restriction. Furthermore, because the current findings highlight that engaging in restrictive eating may also put individuals at especially high risk for subsequent laxative use and body checking, clinicians may find it helpful to additionally target the links between restrictive eating and these behaviors in particular.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the following grants: R01 MH59674 and T32 MH082761 from the National Institute of Mental Health; T32 HL007456 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Footnotes

The authors of this manuscript do not have any conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cooper MJ, Wells A, Todd G. A cognitive model of bulimia nervosa. Brit J Clin Psychol. 2004;43:1–16. doi: 10.1348/014466504772812931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fox JRE, Power MJ. Eating disorders and multi-level models of emotion: An integrated model. Clin Psychol Psychot. 2009;16:240–267. doi: 10.1002/cpp.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heatherton TF, Baumeister RF. Binge eating as escape from self-awareness. Psychol Bull. 1991;110:86–108. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmidt U, Treasure J. Anorexia nervosa: Valued and visible. A cognitive-interpersonal maintenance model and its implications for research and practice. Brit J Clin Psychol. 2006;45:343–366. doi: 10.1348/014466505x53902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waller G. A ‘trans-transdiagnostic’ model of the eating disorders: A new way to open the egg? Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2008;16:165–172. doi: 10.1002/erv.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wonderlich SA, Engel SG, Peterson CB, Robinson M, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, et al. Examining the conceptual model of integrative cognitive-affective therapy for BN: Two assessment studies. Int J Eat Disord. 2008;41:748–754. doi: 10.1002/eat.20551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fairburn CG, Shafran R, Cooper Z. A cognitive behavioural theory of anorexia nervosa. Behav Res Ther. 1998;37:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. Guilford; New York, NY: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dignon A, Beardsmore A, Spain S, Kuan A. ‘Why I won’t eat’: Patient testimony from 15 anorexics concerning the causes of their disorder. J Health Psychol. 2006;11:942–956. doi: 10.1177/1359105306069097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sysko R, Walsh BT, Schebendach J, Wilson GT. Eating behavior among women with anorexia nervosa. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:296–301. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.82.2.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smyth J, Wonderlich S, Crosby R, Miltenberger R, Mitchell J, Rorty M. The use of ecological momentary assessment approaches in eating disorder research. Int J Eat Disord. 2001;30:83–95. doi: 10.1002/eat.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engel SG, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, Crow S, Peterson CB, et al. The role of affect in the maintenance of anorexia nervosa: Evidence from a naturalistic assessment of momentary behaviors and emotion. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013;122:709–719. doi: 10.1037/a0034010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steinglass J, Foerde K, Kostro K, Shohamy D, Walsh BT. Restrictive food intake as a choice – A paradigm for study. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48:59–66. doi: 10.1002/eat.22345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smyth JM, Wonderlich SA, Heron KE, Sliwinski MJ, Crosby RD, Mitchell JE, et al. Daily and momentary mood and stress are associated with binge eating and vomiting in bulimia nervosa patients in the natural environment. J Consult Clin Psych. 2007;75:629–638. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garland EL, Fredrickson B, Kring AM, Johnson DP, Meyer PS, Penn DL. Upward spirals of positive emotions counter downward spirals of negativity: Insights from the broaden-and-build theory and affective neuroscience on the treatment of emotion dysfunctions and deficits in psychopathology. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:849–864. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th American Psychiatric Publishing; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders – Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0) New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York, NY: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stein KF, Corte CM. Ecological momentary assessment of eating-disordered behaviors. Int J Eat Disord. 2003;34:349–360. doi: 10.1002/eat.10194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wheeler L, Reis HT. Self-recording of everyday life events: Origins, types, and uses. J Pers. 1991;59:339–353. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meng X, Rosenthal R, Rubin DB. Comparing correlated correlation coefficients. Psychol Bull. 1992;111:172–175. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heron KE, Scott SB, Sliwinski MJ, Smyth JM. Eating behaviors and negative affect in college women’s everyday lives. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47:853–859. doi: 10.1002/eat.22292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeger SL, Liang KY. An overview of methods for the analysis of longitudinal data. Stat Med. 1992;11:1825–1839. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780111406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stice E, Fisher M, Lowe MR. Are dietary restraint scales valid measures of acute dietary restriction? Unobtrusive observational data suggest not. Psychol Assessment. 2004;16:51–59. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowe MR, Butryn ML. Hedonic hunger: A new dimension of appetite? Physiol Behav. 2007;91:432–439. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowe MR, Thomas JG. Measures of restrained eating: Conceptual evolution and psychometric update. In: Allison DB, Baskin ML, editors. Handbook of assessment methods for eating behaviors and weight-related problems: Measures, theory, and research. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2009. pp. 137–186. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berg KC, Cao L, Crosby RD, Engel SG, Peterson CB, Wonderlich SA, et al. Negative affect and binge eating: Reconciling differences between two analytic approaches in ecological momentary assessment research; Paper presented at the meeting of the Academy for Eating Disorders; New York, NY. Mar, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaye WH, Wierenga CE, Bailer UF, Simmons AN, Bischoff-Grethe A. Nothing tastes as good as skinny feels: The neurobiology of anorexia nervosa. Trends Neurosci. 2013;36:110–120. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fredrickson BL, Joiner T. Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional well-being. Psychol Sci. 2002;13:172–175. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Layous K, Chancellor J, Lyubomirsky S. Positive activities as protective factors against mental health conditions. J Abnorm Psychol. 2014;123:3–12. doi: 10.1037/a0034709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stone AA, Shiffman S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in behavioral medicine. Ann Behav Med. 1994;16:199–202. [Google Scholar]