Abstract

Background

Religion and spirituality (R/S) play an important role in the daily lives of many cancer patients. There has been great interest in determining whether R/S factors are related to clinically-relevant health outcomes. This meta-analytic review examined associations between dimensions of R/S and social health (e.g., social roles and relationships).

Methods

A systematic search of PubMed, PsycInfo, Cochrane Library, and CINAHL databases was conducted, and data were extracted by four pairs of investigators. Bivariate associations between specific R/S dimensions and social health outcomes were examined in a meta-analysis using a generalized estimating equation (GEE) approach.

Results

A total of 78 independent samples encompassing 14,277 patients were included in the meta-analysis. Social health was significantly associated with overall R/S (Fisher z effect size = .20, P< .001), and with each of the R/S dimensions (affective R/S effect size = .32, P< .001; cognitive R/S effect size = .11, P< .01; behavioral R/S effect size = .08, P < .05; and ‘other’ R/S effect size = .13, P < .001). Within these dimensions, specific variables tied to social health included spiritual well-being, spiritual struggle, images of God, R/S beliefs, and composite R/S measures (all P’s < .05). None of the demographic or clinical moderating variables examined was significant.

Conclusions

Several R/S dimensions are modestly associated with patients’ capacity to maintain satisfying social roles and relationships in the context of cancer. Further research is needed to examine the temporal nature of these associations and the mechanisms that underlie them.

Keywords: religion, spirituality, cancer, meta-analysis, quality-of-life

Religious or spiritual (R/S) involvement among cancer patients has been the focus of considerable research activity over the past two decades. These beliefs and practices represent an important resource for many patients as they seek to cope with the burdens of illness.1–3 There are some indications that R/S involvement may be associated with clinically meaningful outcomes, including indices of physical, mental, and social health, but findings have been mixed and the quality of research uneven.4–6

Social health, which reflects patients’ capacity to remain actively engaged in social roles and to feel meaningfully connected with others, is a critical aspect of quality of life and adjustment to cancer.7,8 R/S involvement may contribute to social health through a number of important mechanisms. Indeed, the social implications of religious activity have been highlighted by writers for many years.9–11 Epidemiological findings suggest that religious individuals have larger social networks and more satisfying relationships than their less religious peers.10–12 For many cancer patients, R/S involvement may provide access to practical and emotional assistance during trying circumstances.13,14,15 Moreover, R/S involvement may offer a durable sense of belonging, secure attachment, and social identity16–19 -- ties that may diminish the isolation or role disruption that some patients experience.20–22 Other dimensions of R/S involvement may enhance social health as well (e.g., feelings of spiritual equanimity, beliefs about a beneficent God who is engaged in human affairs, behaviors that embody forgiveness or piety).†,14,23,24 Conversely, of course, relationships with fellow congregants or God may be a source of conflict instead of comfort.25,26 Thus, R/S involvement may contribute to diminished rather than enhanced social well-being.27,28

Although a large number of R/S studies in oncology have included social health outcomes, we are aware of no published meta-analytic reviews. Such efforts would be important in evaluating the current status of this body of research, and delineating areas in need of further work. The current study, which focuses on social health outcomes, is part of a series of meta-analyses; findings regarding physical health and mental health outcomes among oncology patients are reported in companion papers [in review with this journal, masked for review].

Social health may have distinct associations with different dimensions of R/S involvement (e.g., an emotional sense of reverence vs. R/S practices vs. core beliefs). Moreover, these relationships may be colored by the biological imperatives of the disease (e.g., early vs. advanced tumor stage) or the socio-demographic context in which patients are embedded. The primary aim of this meta-analytic review was to examine the strength of relationships between social health and specific dimensions of R/S involvement. The study also examined which R/S dimensions have been evaluated most frequently, and whether relationships between R/S involvement and social health are modified by important clinical and demographic characteristics (e.g., stage, type of malignancy, phase of treatment or survivorship, age, etc.).

Method

Search Strategy

In this systematic review, standardized search strategies were applied to four electronic databases (PubMed, PsycInfo, Cochrane Library, and CINAHL). Controlled search terms specific to each database were used for R/S (e.g., religio*, spiritual*), cancer (e.g., neoplasms, cancer, leukemia), and health outcomes (e.g., measure, scale, outcome*; see Supplementary Material I for further details). The search period covered the earliest publication date available in each database through December, 20, 2013, inclusive. Published articles were supplemented by unpublished studies requested from professional listservs of the Society of Behavioral Medicine (Cancer Special Interest Group), the American Psychosocial Oncology Society (Cancer Survivorship Special Interest Group), and the American Psychological Association, Divisions 36 (Religion and Spirituality) and 38 (Health Psychology).

Inclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they: (1) were published in English; (2) included an adult sample (≥18 years old) with a diagnosis of cancer; (3) assessed an R/S variable; (4) evaluated a social health outcome (detailed below); and (5) reported an effect size representing the bivariate association between R/S and social health variables. Data were included from observational investigations, instrument validation studies, and clinical trials (if derived from pretreatment baseline assessments or from control subjects). Exclusion criteria included: (1) qualitative assessments of R/S or health; (2) R/S intervention studies in which the intervention was the only index of R/S; (3) needs assessments of R/S or health; and (4) pediatric or caregiver samples.

Coding R/S Variables and Social Health

R/S involvement is recognized as a complex, multidimensional construct, and there are many ways of categorizing its components.29 In the current study, it was conceptualized a priori as encompassing distinct affective, behavioral, and cognitive dimensions (for further discussion of this model, please see Salsman et al.,30 in review with this journal). The affective dimension was defined as the subjective emotional experience of R/S, including spiritual well-being or connection to the sacred, as well as struggle with or alienation from God. The behavioral dimension was defined as use of R/S practices (e.g., religious service attendance, public or private prayer, meditation) and R/S coping efforts (e.g., reminding oneself of God’s purpose or comfort, seeking spiritual support). The cognitive dimension encompassed R/S beliefs and perceptions, such as the salience of R/S, intrinsic/extrinsic religious orientation, images of God, specific R/S beliefs, causal attributions for illness, and perceived spiritual growth or decline. Measures that did not fit well into these three dimensions or that encompassed multiple dimensions were included in an ‘other’ category (e.g., composite measures, religious affiliation, R/S support).

Social health encompassed the extent of involvement in social roles, relationships, or activities, and the perceived quality of that involvement. We further distinguished among three domains of social health: social well-being (involving favorable interactions), social distress (involving conflicted or unsatisfying interactions), and social support (involving the perceived quality of emotional or instrumental assistance that was available or received; also included were social network indices assessed in 1 study) (see the NIH Toolbox Social Relationship Scales31 for a similar conceptual approach).

Screening Procedures

The review team included four pairs of raters, all of whom had expertise in this field and held advanced degrees. Each abstract was reviewed by a pair of raters to determine which articles warranted full review. Studies possibly meeting inclusion criteria underwent full-text review. Each full-text article was reviewed by a pair of raters; each rater independently evaluated the study and abstracted data for entry into a database. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus within pairs of raters. In the review process, R/S measures were classified as affective, behavioral, cognitive, or ‘other,’ as noted above. (In the parent project, health outcome measures were categorized as social, physical, or mental; the social measures are the focus of this report.) When full text articles could not be located or provided insufficient data, efforts were made to contact authors for additional information.

Effect Size Measures

Studies that reported bivariate associations between R/S and social health variables were included in the meta-analysis, as noted above. These effect size statistics included Pearson product-moment or Spearman correlation coefficients, standardized mean differences between groups, and odds ratios based on dichotomizing two continuous variables. When an effect size estimate was not reported in the article, an attempt was made to calculate it based on the data provided in the publication or from authors who supplied supplementary data. Excluded from the analyses were multivariable measures of association (e.g., regression or partial correlation coefficients), because they are not directly comparable to measures of bivariate association and present notable analytic challenges.32

Effect sizes were coded in a standard manner such that a positive relationship between an R/S variable and a social health outcome reflected higher levels of R/S and better social health. For purposes of meta-analysis, all reported effect sizes were converted to the Fisher z scale, which is a non-linear transformation of Pearson’s correlation measure. The Fisher z scale was chosen because it normalizes and stabilizes the sampling variance of Pearson correlation coefficients and because it has an unbounded range.33 Transformation to the z-scale has very little effect in the range of correlations found in the present analysis (−.40 < z < .40)-- thus, the value of z-scale estimates reported below are nearly equivalent to the value of corresponding Pearson’s correlation coefficients.

Moderator Variables

Relationships between R/S variables and social health outcomes might be influenced by a number of demographic and clinical characteristics. Potential moderating factors were coded for each article, including sample-level summaries of demographic (i.e., gender, age, race, and geographic region) and clinical (i.e., type of malignancy, stage, and phase in the trajectory of treatment or recovery) variables.

Meta-analytic Procedures

Many studies reported effect size data for several measures of R/S and/or several measures of health outcomes derived from a common sample of participants,†† leading to dependence of the effect size estimates nested within a study.34 To address this concern, a generalized estimating equation (GEE) approach was used to estimate average effect sizes and meta-regression coefficients. In conjunction with robust variance estimation, this approach produces valid estimates of average effects, standard errors, and hypothesis tests even when effect sizes drawn from common studies are correlated rather than independent .35 For inference regarding single regression coefficients in the meta-analysis (e.g., tests for differences in average effect size between two R/S dimensions), we employed robust t-tests involving small-sample corrections proposed by Tipton.36 For simultaneous inference regarding multiple regression coefficients (e.g., tests for differences among three or more dimensions), we used robust Wald test statistics that follow chi-square reference distributions when the number of independent studies is large.††† Weights for the GEE analysis were determined based on a hierarchical model containing between-study and within-study random effects.

GEE analyses were used to evaluate the associations of each R/S dimension (affective, behavioral, cognitive, ‘other’) with social health. We examined which R/S dimensions had been studied most frequently (i.e., number of studies and number of effect sizes). For R/S dimensions with significant effects, additional GEE analyses were used to probe which specific R/S variables within each broad dimension were most strongly tied to social health. Similar GEE analyses examined whether there were differential associations with different types of social health outcomes. Finally, potential moderator variables were tested to determine whether associations between overall R/S and social health differed among patient subgroups.

Results

Study Selection

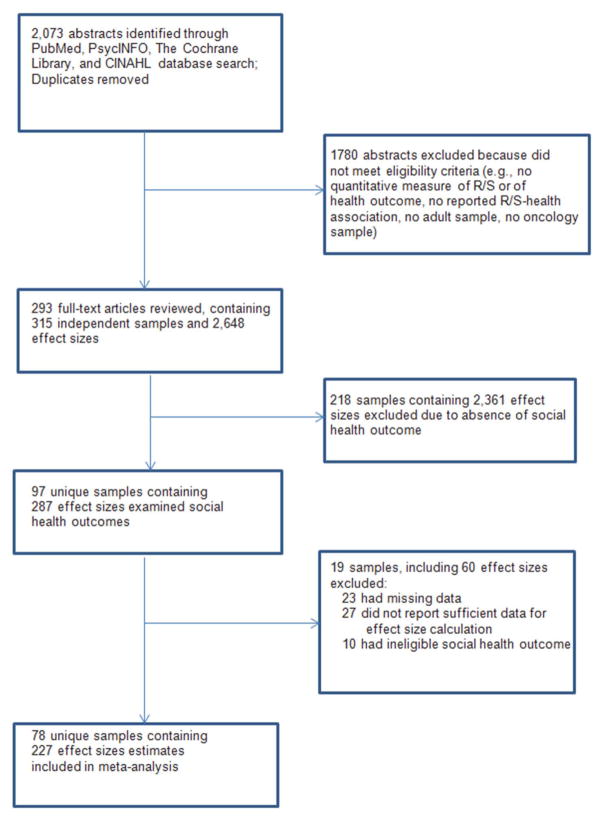

A total of 2073 abstracts were identified through electronic databases (see Figure 1). Following a systematic search, 293 full-text articles were examined containing 315 unique samples, which netted 2,648 effect sizes regarding R/S variables and health outcomes. Of these, 97 samples encompassing 287 effect sizes included a social health outcome. We eliminated 60 of these effect sizes from the analyses because of missing data (23 effect sizes), because they did not measure a bivariate relationship (27 effect sizes), or because the outcome measure was excluded†††† (10 effect sizes). The final analyses included 227 effect sizes derived from 78 unique samples (see online Supplementary Material II for a list of the characteristics of these studies).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of selection of studies

Study Participants

The analyses included 14,277 patients drawn from 78 separate samples. Across studies, the mean age was 57.1 (SD = 7.3), and the mean percentage of females was 65.0% (SD = 27.1). Fifty-six percent of the studies were conducted in North America, and among these, the mean proportion of Caucasians was 73.1% (SD= 31.7). Most studies included patients with mixed disease sites (53%); 24% focused solely on breast cancer patients and 23% focused on another single malignancy. Ten percent of studies evaluated patients with only early-stage disease, 17% included patients with only advanced tumors, 42% enrolled patients with diverse stages of disease, and 31% of reports did not include this variable. With respect to the trajectory of illness, 28% of studies focused on the period of diagnosis or active treatment, 19% evaluated post-treatment survivorship, 10% assessed patients at the end of life, and 42% included patients at diverse phases of the illness continuum.

Meta-Analyses

Effects of different R/S dimensions

The association between overall R/S involvement (collapsing across all R/S dimensions) and social health was statistically significant (Fisher z effect size = .20, P < .0001) in the GEE model (Table 1). A subsequent analysis examined the separate associations of each of the R/S dimensions (Table 1); each dimension was significantly related to social health (effect sizes ranged from .32 for affective R/S to .08 for behavioral R/S; all P’s < .05). The effect size estimate for affective R/S was significantly larger than those for behavioral R/S (P < .001), cognitive R/S (P < .001), and ‘other’ R/S (P < .001), which did not differ from each other.

Table 1.

Estimated Associations between Religious/Spiritual Dimensions and Social Health

| Religion/Spirituality Dimension | Estimate (SE) | 95% CI | Number of studies | Number of effect sizes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall R/S | .20 (.02)*** | [.16, .24] | 78 | 227 |

| Affective | .32 (.03)*** | [.25, .37] | 39 | 112 |

| Behavioral | .08 (.03)* | [.02, .15] | 17 | 38 |

| Cognitive | .10 (.03)** | [.04, .17] | 18 | 45 |

| Other | .13 (.03)*** | [.05, .20] | 22 | 32 |

Abbreviations R/S = religion/spirituality; SE = standard error, CI = confidence interval

Note: effect sizes are Fisher z-scale correlations

P<0.05,

P < 0.01

P <0.001

Additional analyses provided a closer look at some of the major R/S variables within each broad dimension (i.e., within the categories of affective, cognitive, behavioral, and ‘other’ R/S). Specific R/S variables were included in the GEE regression model if they had been examined in at least 3 independent studies yielding at least 6 effect sizes (the number of available effect sizes for each variable in the model ranged from 6 to 102). As indicated in Table 2, associations with social health were significant for spiritual well-being and spiritual distress (both in the affective dimension), God image and R/S beliefs (both in the cognitive dimension), and a composite index (based on measures that used elements from several R/S dimensions); these effect sizes ranged from .13 to 33. Neither of the specific variables examined within the behavioral R/S dimension was statistically distinguishable from zero (Table 2).

Table 2.

Estimated Associations between Specific Religious/Spiritual Variables and Social Health

| Religious/Spiritual (R/S) Variable | Estimate (SE) | 95% CI | Number of studies | Number of effect sizes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spiritual distress (affective) | .24 (.07)* | .07, .40 | 7 | 9 |

| Spiritual well-being (affective) | .33 (.03)*** | .27, .40 | 33 | 102 |

| Private R/S activities (behavioral) | .11 (.06) | −.19, .40 | 3 | 11 |

| R/S coping (behavioral) | .06 (.05) | −.04, .16 | 14 | 25 |

| God image (cognitive) | .19 (.03)* | .03, .36 | 3 | 11 |

| Locus of control (cognitive) | .07 (.08) | −.23, .38 | 3 | 6 |

| R/S beliefs (cognitive) | .13 (.02)* | .06, .20 | 4 | 7 |

| Spiritual growth (cognitive) | .09 (.13) | −.33, .51 | 4 | 6 |

| Composite measures (other) | .13 (.02)*** | .07, .18 | 16 | 22 |

Abbreviations R/S = religion/spirituality; SE = standard error, CI = confidence interval

Note: effect size estimates are Fisher z-scale correlations

P<0.05,

P < 0.01

P <0.001

Across samples, the most commonly studied R/S dimension was the affective one, which was evaluated in roughly twice as many investigations as were the other R/S dimensions (Table 1). This difference was due largely to the widespread use of a particular measure of affective R/S, the FACIT-Spiritual Well-being Scale.37 Sensitivity analysis evaluated whether associations with social health differed for this instrument vs. other measures of spiritual well-being. There were no significant differences (P = .48).

Effects on Different Social Health Outcomes

The most commonly studied social health variable was social well-being, for which 117 effect sizes were available, compared with 41 for social distress and 69 for social support. Each type of social health outcome was significantly related to overall R/S (effect sizes = .17 to .22; all P’s <.01). There were no significant differences among these effects (all P’s > .20).

Moderator analyses

Moderator analyses examined whether the relationship between overall R/S involvement and social health differed as a function of pertinent demographic factors (age, gender, geographic setting) or clinical characteristics (cancer type, stage, and phase in the trajectory of illness). None of these variables had significant effects (all P’s ≥ .08).

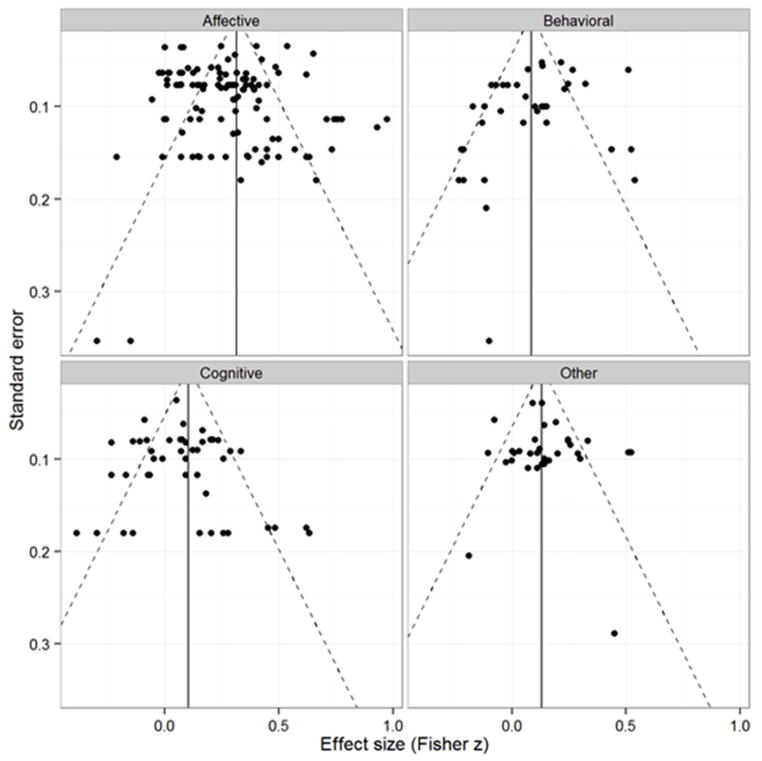

Reporting Bias

The threat of reporting or publication bias was assessed through visual inspection of funnel plots of the effect sizes for each R/S dimension (see Figure 2). The plots do not display noticeable asymmetry that would indicate reporting bias, with the possible exception of the ‘other’ R/S dimension. A cluster-robust variant of Egger’s test did not detect reporting bias (P = .95). The marked heterogeneity of effects within each R/S dimension is apparent from the plots. We also examined effect sizes that had been excluded from the meta-analysis due to missing data; of these, 13 effect sizes from 3 samples were reported to be statistically nonsignificant in the original studies. In sensitivity analyses, we imputed a value of zero for each of these effect sizes and included them in the meta-analysis; this did not alter the results described above in any meaningful way.

Figure 2.

Funnel plots of effect sizes versus standard errors for each R/S domain

Discussion

The capacity to remain actively engaged with others and to maintain satisfying relationships, despite the demands of the illness, is a critical concern for cancer patients. The current meta-analysis, based on a large number of independent studies, suggests that social health is related to overall R/S involvement, and to each of the R/S dimensions examined (i.e., affective, cognitive, behavioral, and other). These effects varied in magnitude but were generally modest. To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to examine these relationships.

The affective R/S dimension displayed the strongest associations with social health. More specifically, individuals who reported deriving a sense of equanimity, peacefulness, or harmony from their R/S pursuits (i.e., spiritual well-being) demonstrated the most favorable levels of social health (Fisher z effect size =.33). Conversely, patients who experienced a sense of struggle with or alienation from their faith reported lower levels of social health (effect size = .24). These findings highlight the importance of attending to negative as well as positive R/S experiences. The measures of R/S struggle included in this review focused predominantly on difficulties with God. Additional research is needed to clarify the effects of struggle with religious leaders or members of the religious community.38

The effects of cognitive, behavioral, and ‘other’ (mixed) R/S dimensions were statistically significant but small (effect sizes ranged from .08 to .13). These dimensions represented conceptually coherent clusters of R/S variables, but they remained relatively broad categories. Additional analyses sought to make finer distinctions as a basis for further research. Within the cognitive R/S dimension, there were indications that social health was related to more benign images of God (e.g., perceptions of a benevolent rather than an angry or distant God; effect size =.19), and stronger R/S beliefs (e.g., convictions that a personal God can be called upon for assistance; effect size = .13). In addition, social health was modestly associated with composite measures of R/S involvement (i.e., those that incorporated mixed elements of cognitive, behavioral, and affective dimensions; effect size = .13). Investigations that further explore these areas, including in particular R/S images or beliefs that are specific to the illness and defined within their cultural context, would offer a useful contribution.

In contrast to these findings, no significant effects emerged for other R/S variables such as positive religious coping (e.g., turning to one’s faith to manage the burdens of illness), private religious activities (e.g., private prayer or meditation), or God locus of control (e.g., perceptions that health is controlled mainly by God rather than clinicians or luck). These analyses were based on relatively few independent studies, so firm conclusions await further research. Still, the lack of support for positive religious coping seems notable, given the larger number of independent studies that contributed to this estimate (14 samples) and the greater theoretical and empirical attention that this construct has commanded. The current meta-analytic findings are in line with the inconsistent results previously observed across individual studies of positive religious coping, many of which reported null results.4,5

This study also evaluated whether the relationships between R/S dimensions and social health are moderated by a number of clinical and demographic variables. None of these moderating effects was significant, which suggests that the relationships reported here are fairly consistent across subgroups of patients who differ on important characteristics, including stage, type of malignancy, phase in the trajectory of treatment, age, gender, and geographical region. Thus, relationships between R/S involvement and social health may have more to do with the personal qualities that patients bring to the illness than with the particularities of their disease. However, our ability to detect moderator effects was limited by the use of study-level aggregate values of clinical/demographic variables (e.g., mean age in the sample), rather than individual-level patient data, which would have provided a more powerful test. Moreover, some clinical (e.g., terminally ill) and demographic (e.g., young adults, African Americans) subgroups have been little studied, and the potential influence of personal and cultural factors has yet to be carefully examined, so additional research regarding moderator effects clearly would be useful.

Conclusions about associations between R/S involvement and social health are tempered by a number of limitations in the existing literature. The great majority of studies included in this meta-analysis were cross-sectional; thus, it is difficult to draw temporal or causal conclusions about relationships between R/S factors and social health. It seems likely that these associations are reciprocal (e.g., some social ties may promote R/S involvement as well as vice versa). Longitudinal investigations are becoming more common, and the results of this study clearly point to the need for those designs in future research to help clarify temporal effects. Moreover, the quality of studies reviewed was highly variable. Many included heterogeneous samples of patients with diverse types of malignancies (53%), stages of disease (42%), or phases in the illness trajectory (42%). Some failed to report basic clinical characteristics (e.g., 31% did not specify tumor classification). Almost all were based on self-report measures. In general, more recent investigations tend to be characterized by fewer methodological limitations than earlier ones, but concerns remain about poorly designed R/S measures, conceptual confusion about what these instruments actually assess, incomplete description of accrual rates or sample characteristics, or failure to account for the effects of basic clinical variables.

Moreover, social health was rarely the primary focus in these studies; rather, it was usually included as one of a number of health endpoints that were evaluated. R/S variables seem highly relevant for several theoretical models of relationship functioning or social health (e.g., attachment theory, interpersonal circumplex model, relationship goal frameworks);39–42 there is a need for further R/S investigations that specifically target social health as the primary outcome, using theoretically-grounded hypotheses.

Limitations of the meta-analysis warrant consideration as well. The current analyses evaluated the social health correlates of several dimensions of R/S involvement (i.e., affective, cognitive, behavioral, ‘other’), and within these categories, some specific R/S variables (e.g., spiritual distress, spiritual well-being, God image, etc.). Notably, however, there were insufficient numbers of studies to examine the independent effects of other important R/S variables within these larger dimensions (e.g., religious service attendance, intrinsic religious orientation, particular types of R/S coping strategies). It is possible that the effects of some of these variables were masked by their inclusion in broader R/S clusters. Thus, the role of these specific factors awaits further testing as the literature expands. In particular, variables that capture the functions that R/S involvement serves in the day-to-day lives of individuals with cancer (e.g., specific coping strategies or efforts to elicit support), rather than only its structural or descriptive elements (e.g., denomination, frequency of religious service attendance), will be especially important to examine in future reviews.13,14,43 Moreover, the meta-analysis evaluated bivariate relationships; therefore associations between R/S dimensions and social health are not adjusted for covariates. In addition, the current review did not focus on mediating effects. For example, stronger social relationships are often construed as a core mechanism linking R/S involvement with better physical or mental health outcomes.13,44,45 These important associations are beyond the scope of the current report and warrant a separate review.

Conclusions

In sum, evidence suggests that several R/S dimensions are modestly associated with social health outcomes. These findings stem from analysis of over 14,000 cancer patients drawn from 78 independent samples. Results did not seem to be affected by reporting bias, consistent with the broad range of studies included in this review. Findings provide an important foundation for future research. Additional work is needed to clarify the temporal ordering of these relationships, to further explore potential moderating factors (e.g., collectivist vs. individualist cultural characteristics), and to evaluate more closely the effects of specific R/S variables (especially those that reflect illness-related rather than only generic R/S experiences, and functional rather than structural elements).

These meta-analytic results help integrate the expansive literature regarding R/S factors and social health, and provide guideposts for the road ahead. A greater understanding of these relationships may illuminate significant resources and vulnerabilities that some oncology patients encounter over the course of illness. These relationships may have salient implications for patient-centered care and quality of life,46 in view of the large proportion of cancer patients who report strong R/S commitments.1–3 Clearly, even small effects may have a broad impact on a population level. Within clinical settings, there has been a growing emphasis on addressing R/S factors, and several practice guidelines now recommend providing screening and appropriate referrals for oncology patients with spiritual concerns.47,48 Current findings also help advance the research agenda by identifying notable effects, delineating R/S factors that have received insufficient attention, and highlighting areas that require more rigorous evaluation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the NIH under award number K07CA158008. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Plausible pathways that might link these R/S variables with social health outcomes in particular contexts may include, among others, positive affect, affiliation, positive attributions, cooperation, forbearance, and prosocial behavior.49–54

A few studies reported results from more than one independent sample of participants. In these cases, each unique sample was treated as an independent study. For simplicity of presentation, the text does not distinguish between independent studies and independent samples reported in the same study.

We are not aware of any small-sample corrections for robust tests of more than one regression coefficient.

The “relationship with doctor” item on early versions of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale7 was dropped from subsequent versions of the instrument due to psychometric concerns; therefore it was excluded from the current analysis.

The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Balboni TA, Vanderwerker LC, Block SD, et al. Religiousness and spiritual support among advanced cancer patients and associations with end-of-life treatment preferences and quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:555–560. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silvestri GA, Knittig S, Zoller JS, Nietert PJ. Importance of faith on medical decisions regarding cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1379–1382. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feher S, Maly RC. Coping with breast cancer in later life: the role of religious faith. Psycho-Oncol. 1999;8:408–416. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199909/10)8:5<408::aid-pon409>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thune-Boyle IC, Stygall JA, Keshtgar MR, Newman SP. Do religious/spiritual coping strategies affect illness adjustment in patients with cancer? A systematic review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:151–164. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sherman AC, Simonton S. Spirituality and cancer. In: Plante TG, Thoresen AC, editors. Spirit, Science, and Health: How the Spiritual Mind Fuels Physical Wellness. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2007. pp. 157–175. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schreiber JA, Brockopp DY. Twenty-five years later—what do we know aobut religion/spirituality and psychological well-being among breast cancer survivors? A systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:82–94. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Durkheim E. Elementary forms of religious life. London: Allen & Unwin; 1915. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellison CG, George LK. Religious involvement, social ties, and social support in a southeastern community. J Sci Study Religion. 1994;33:46–61. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayward RD, Krause N. Trajectories of disability in older adulthood and social support from a religious congregation: a growth curve analysis. J Behav Med. 2013;36:354–360. doi: 10.1007/s10865-012-9430-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strawbridge WJ, Shema SJ, Cohen RD, Kaplan GA. Religious attendance increases survival by improving and maintaining good health behaviors, mental health, and social relationships. Ann Behav Med. 2001;23:68–74. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2301_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howsepian BA, Merluzzi TV. Religious beliefs, social support, self-efficacy and adjustment to cancer. Psycho-Oncol. 2009;18:1069–1079. doi: 10.1002/pon.1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pargament KI. The Psychology of Religion and Coping: Theory, Research, and Practice. New York: Guilford; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nairn RC, Merluzzi TV. The role of religious coping in adjustment to cancer. Psychooncol. 2003;12:428–441. doi: 10.1002/pon.654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gauthier LR, Rodin G, Zimmermann C, et al. Acceptance of pain: a study of patients with advanced cancer. Pain. 2009;143:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenfield EA, Marks NF. Religious social identity as an explanatory factor for associations between more frequent formal religious participation and psychological well-being. Int J Psychol Relig. 2007;17:245–259. doi: 10.1080/10508610701402309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamilton JB, Stewart BJ, Crandell JL, Lynn MR. Development of the Ways of Helping Questionnaire: a measure of preferred coping strategies for older African American cancer survivors. Res Nurs Health. 2009;32:243–259. doi: 10.1002/nur.20321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Cook JM. Birds of a feather: homophily in social networks. Ann Rev Sociol. 2001;27:415–444. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deckx L, van den Akker M, Buntinx F. Risk factors for loneliness in patients with cancer: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2014;18:466–477. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobs M, Macefield RC, Elbers RG, et al. Meta-analysis shows clinically relevant and long-lasting deterioration in health-related quality of life after esophageal cancer surgery. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:1155–1176. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0576-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Poel MW, Oerlemans S, Schouten HC, et al. Quality of life more impaired in younger than in older diffuse large B cell lymphoma survivors compared to a normative population: a study from the population-based PROFILES registry. Ann Hematol. 2014;93:811–819. doi: 10.1007/s00277-013-1980-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawler-Row KA, Karremans JC, Scott C, Edlis-Matityahou M, Edwards L. Forgiveness, physiological reactivity and health: the role of anger. Int J Psychophysiol. 2008;68:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steffen PR, Masters KS. Does compassion mediate the intrinsic religion-health relationship? Ann Behav Med. 2005;30:217–224. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3003_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fitchett G, Murphy PE, Kim J, et al. Religious struggle: prevalence, correlates and mental health risks in diabetic, congestive heart failure, and oncology patients. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2004;34:179–196. doi: 10.2190/UCJ9-DP4M-9C0X-835M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Exline JJ, Park CL, Smyth JM, Carey MP. Anger toward God: social-cognitive predictors, prevalence, and links with adjustment to bereavement and cancer. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2011;100:129–148. doi: 10.1037/a0021716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sherman AC, Plante TG, Simonton S, Latif U, Anaissie EJ. Prospective study of religious coping among patients undergoing autologous stem cell transplantation. J Behav Med. 2009;32:118–128. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9179-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schreiber JA. Image of God: effect on coping and psychospiritual outcomes in early breast cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2011;38:293–301. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.293-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working Group. Multidimensional Measurement of Religiousness/Spirituality for Use in Health Research. J Kalamazoo, MI: John E. Fetzer Institute; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salsman JM, Fitchett G, Merluzzi TV, Sherman AC, Park CL. Religion, spirituality, and health outcomes in cancer: A case for a meta-analytic investigation. 2014. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cyranowski JM, Zill N, Bode R, et al. Assessing social support, companionship, and distress: National Institute of Health (NIH) toolbox adult social relationship scales. Health Psychol. 2013;32:293–301. doi: 10.1037/a0028586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Becker BJ, Wu M-J. The synthesis of regression slopes in meta-analysis. Statistical Sci. 2007;22:414–429. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borenstein M. Effect sizes for continuous data. In: Cooper HM, Hedges LV, Valentine JC, editors. The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2009. pp. 221–236. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gleser LJ, Olkin I. Stochastically dependent effect sizes. In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, Valentine JC, editors. The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2009. pp. 357–376. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hedges LV, Tipton E, Johnson MC. Robust variance estimation in meta-regression with dependent effect size estimates. Research Synthesis Methods. 2010;1:39–65. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tipton E. Small sample adjustments for robust variance estimation with meta-regression. Psychological Methods. 2014 doi: 10.1037/met00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, Hernandez L, Cella D. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy--Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp) Ann Behav Med. 2002;24:49–58. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burker EJ, Evon DM, Sedway JA, Egan T. Religious and non-religious coping in lung transplant candidates: does adding God to the picture tell us more? J Behav Med. 2005;28:513–526. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manne SL, Badr H. Intimacy and relationship processes in couples’ psychosocial adaptation to cancer. Cancer. 2008;112:2541–2555. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Canevello A, Crocker J. Interpersonal goals and close relationship processes: potential links to health. Soc Person Psychol Compass. 2011;5:346–358. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pietromonaco PR, Uchino B, Dunkel Schetter C. Close relationship processes and health: implications of attachment theory for health and disease. Health Psychol. 2013;32:499–513. doi: 10.1037/a0029349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jordan KD, Masters KS, Hooker SA, Ruiz JM, Smith TW. An interpersonal approach to religiousness and spirituality: implications for health and well-being. J Pers. 2014;82:418–431. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sherman AC, Simonton S, Latif U, Spohn R, Tricot G. Religious struggle and religious comfort in response to illness: health outcomes among stem cell transplant patients. J Behav Med. 2005;28:359–367. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perez JE, Smith AR, Norris RL, Canenguez KM, Tracey EF, DeCristofaro SB. Types of prayer and depressive symptoms among cancer patients: the mediating role of rumination and social support. J Behav Med. 2011;34:519–530. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9333-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ai AL, Park CL, Huang B, Rodgers W, Tice TN. Psychosocial mediation of religious coping styles: a study of short-term psychological distress following cardiac surgery. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2007;33:867–882. doi: 10.1177/0146167207301008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fitchett G, Winter-Pfändler U, Pargament KI. Struggle with the divine in Swiss patients visited by chaplains: prevalence and correlates. J Health Psychol. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1359105313482167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Distress Management Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Cancer Network. 2003;1:344. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2003.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.National Concensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. [accessed June 11, 2014];Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. Available from URL: http://www.nationalconsensusproject.org/guideline.pdf.

- 49.Saroglou V. Is religion not prosocial at all? Comment on Galen. Psychol Bull. 2012;138:907–912. doi: 10.1037/a0028927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lambert NM, Fincham FD, Stillman TF, Graham SM, Beach SR. Motivating change in relationships: can prayer increase forgiveness? Psychol Sci. 2010;21:126–132. doi: 10.1177/0956797609355634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Kleef GA, De Dreu CK, Manstead AS. An interpersonal approach to emotion in social decision making: the emotions as social information model. Adv Exper Soc Psychol. 2010;42:45–96. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Forgas JP. On feeling good and getting your way: mood effects on negotiator cognition and bargaining strategies. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74:565–577. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.3.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fincham FD, Beach SR, Davila J. Longitudinal relations between forgiveness and conflict resolution in marriage. J Fam Psychol. 2007;21:542–545. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.3.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Impett EA, Gable SL, Peplau LA. Giving up and giving in: the costs and benefits of daily sacrifice in intimate relationships. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;89:327–344. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.