Abstract

Participatory ergonomics (PE) can promote the application of human factors and ergonomics (HFE) principles to healthcare system redesign. This study applied a PE approach to redesigning the family-centered rounds (FCR) process to improve family engagement. Various FCR stakeholders (e.g., patients and families, physicians, nurses, hospital management) were involved in different stages of the PE process. HFE principles were integrated in both the content (e.g., shared mental model, usability, workload consideration, systems approach) and process (e.g., top management commitment, stakeholder participation, communication and feedback, learning and training, project management) of FCR redesign. We describe activities of the PE process (e.g., formation and meetings of the redesign team, data collection activities, intervention development, intervention implementation) and present data on PE process evaluation. To demonstrate the value of PE-based FCR redesign, future research should document its impact on FCR process measures (e.g., family engagement, round efficiency) and patient outcome measures (e.g., patient satisfaction).

Keywords: participatory ergonomics, family-centered rounds, healthcare system redesign, pediatric hospital, checklist

1. Introduction

Human Factors and Ergonomics (HFE) has been proposed as a key systems engineering approach to redesign healthcare work systems and processes and, therefore, improve the quality and safety of care (Carayon 2011; Kaplan et al. 2013; Reid et al. 2005). A systematic review on HFE-based healthcare system redesign (Xie and Carayon 2014) showed that HFE has been used to redesign a range of healthcare work systems (e.g., clinical tasks, medical devices, health IT, physical environment) and processes (e.g., care processes) in various clinical settings (e.g., anesthesia, emergency department, primary care, surgery, home care). The application of an HFE approach to healthcare system redesign, however, faces various challenges, such as lack of HFE knowledge and professional boundaries in healthcare resulting in mono-disciplinary communities of practice (Carayon 2010; Carayon and Xie 2011). A participatory ergonomics (PE) approach can address these challenges and promote HFE application to healthcare system redesign (Bohr, Evanoff and Wolf 1997; Evanoff, Bohr and Wolf 1999).

PE is a macroergonomic approach to work system design, which emphasizes the involvement of people in “planning and controlling a significant amount of their own work activities, with sufficient knowledge and power to influence both processes and outcomes in order to achieve desirable goals” (Wilson, Haines and Morris 2005). PE has been applied across a range of industries, such as manufacturing (Halpern and Dawson 1997; Liker, Nagamachi and Lifshitz 1989; St-Vincent, Chicoine and Beaugrand 1998), food (Moore and Garg 1997), services (Haims and Carayon 1998; Mansfield and Armstrong 1997; Vink et al. 1995), construction (de Jong and Vink 2000; de Jong and Vink 2002; de Looze et al. 2001), and transportation (Laitinen, Saari and Kuusela 1997). The application of PE to healthcare system redesign, however, is limited. A 1998 review of 41 PE case studies found no studies in healthcare (Haines and Wilson 1998), while a 2010 review identified only 3 of 52 PE studies that were conducted in healthcare (van Eerd et al. 2010). PE studies in healthcare focus on physical ergonomic issues (e.g., musculoskeletal disorders) related to individual tasks in specific jobs (e.g., nurses performing patient handling tasks) (Bohr, Evanoff and Wolf 1997; Fragala and Santamaria 1997; Udo et al. 2006). To our knowledge, there is no published application of PE to the redesign of complex care processes. In this study, we show how PE can be applied to redesign the complex process of family-centered rounds (FCR) to improve family engagement.

2. Background

2.1 Family engagement in FCR

FCR are “interdisciplinary work rounds at the bedside in which the patient and family share in the control of the management plan as well as in the evaluation of the process itself” (Sisterhen et al. 2007). FCR differ from traditional “conference room” rounds by actively involving patients and families in daily discussion of care and clinical decision-making. In the pediatric setting, hospitalized children are particularly vulnerable to medical errors since they have limited ability to participate in clinical decision-making and to recognize and report adverse events (Kaushal et al. 2001). Engaging families in the care of hospitalized children has been suggested to improve the quality and safety of care (Committtee on Drugs and Committee on Hospital Care 2003). FCR provide a consistent venue for family engagement and, therefore, are recommended as standard inpatient practice (Committee on Hospital Care and Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care 2012).

A 2010 study of pediatric hospitalists in the United States and Canada showed that FCR had become the most common type of rounds (Mittal et al. 2010). Despite the widespread shift from rounding in the physician conference room to rounding at the bedside, discrepancies between theory and practice of FCR have been identified (Subramony, Hametz and Balmer 2014). System barriers can hinder family engagement in FCR, for example, disruption of nursing workflow, longer duration of rounds, large healthcare team size, and room constraints (Carayon et al. 2011; Carayon, Li, et al. 2014; Mittal et al. 2010). To truly engage families in FCR and to enhance the safety of care for hospitalized children, these system barriers need to be addressed and the FCR process and related work system need to be redesigned (Kelly et al. 2013).

2.2 Local problem

FCR were implemented on various inpatient services at a 61-bed children’s hospital in the Midwestern US in 2007 during the transition to a new hospital facility. The hospital leadership was strongly supportive of family-centered care and committed to FCR. To enhance family-centeredness, the hospital leadership engaged researchers to understand how to address any barriers to family engagement in FCR and implement effective interventions to improve family engagement in FCR. A five-year research project funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Cox, PI) was initiated to: (1) assess the effect of family engagement in FCR on the safety of care for hospitalized children, (2) design and implement an intervention addressing common barriers to family engagement in FCR, and (3) assess the impact of the intervention on family engagement in FCR and the safety of care for hospitalized children. We focused on the second aim of the research project in which we applied a PE approach to the redesign of the FCR process. In this paper, we describe activities of the PE process (e.g., formation and meetings of the redesign team, data collection activities, intervention development and implementation) and present data on the evaluation of the PE process. The impact of the intervention developed in the PE process will be reported in forthcoming manuscripts.

2.3 Conceptual framework

We emphasize two key characteristics of PE in FCR redesign: (1) participation of different FCR stakeholders in the redesign and (2) application of HFE principles in the content and process of FCR redesign. FCR involves multiple stakeholders, including patients and families and healthcare providers from different professional groups (e.g., physicians, nurses) and organizational levels (e.g., frontline providers, management). A PE approach requires the participation of all stakeholders (who can affect or are affected by the FCR process) in the redesign. In addition, PE emphasizes the integration of HFE in both the content (what is the redesign) and process (how the redesign is implemented) of FCR redesign (Haims and Carayon 1998). The content of FCR redesign is about changes in the work system that can improve the FCR process and consequently family engagement (Carayon et al. 2006). While individual work system elements need to be designed according to HFE principles (Carayon, Alvarado and Hundt 2007; Sanders and McCormick 1993; Weinger, Wiklund and Gardner-Bonneau 2011; Zhang et al. 2003), interactions between work system elements should be optimized using the systems approach of HFE (Carayon et al. 2006; Waterson 2009; Wilson 2000, 2014). The process of FCR redesign is about how changes in the work system are implemented. HFE principles, such as top management commitment, stakeholder participation, communication and feedback, learning and training, and project management, have been proposed to guide the implementation process and ensure work system changes are accepted and sustained (Carayon, Alyousef and Xie 2012; Endsley 1994; Karsh 2004; Smith and Carayon 1995).

In addition to considering the two key characteristics of PE (i.e. multiple stakeholders, and process and content of redesign), we used the SEIPS (Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety) model of work system and patient safety (Carayon et al. 2006; Carayon, Wetterneck, et al. 2014) to guide the PE process. The SEIPS model is a systems engineering model anchored within HFE. By integrating Donabedian’s structure-process-outcome model (Donabedian 1988) and the work system model developed by Carayon and Smith (Carayon 2009; Carayon and Smith 2000; Smith and Carayon 2000; Smith and Carayon-Sainfort 1989), the SEIPS model highlights how work system design (structure) is linked to patient safety (outcome) through care processes.

Finally, we performed a formative evaluation (Stetler et al. 2006) to assess and continuously improve the PE process (Andersen and Zebis 2014; Durlak and DuPre 2008; Griffin et al. 2010). Linnan and Steckler (2002) proposed a framework with seven components of process evaluation: context, reach, dose delivered, dose received, fidelity, implementation, and recruitment. In this study, we used various methods to collect information on four components of the PE process: minutes and surveys of redesign team meetings provided information on reach, dose delivered and dose received, while surveys of training sessions and pilot study data on the use of the intervention provided information on fidelity.

3. Organization of the PE Process

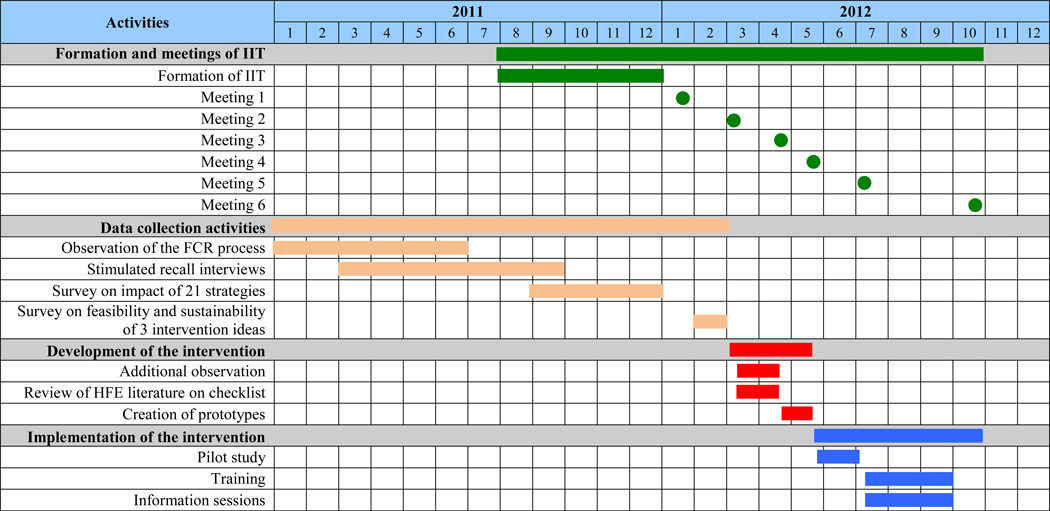

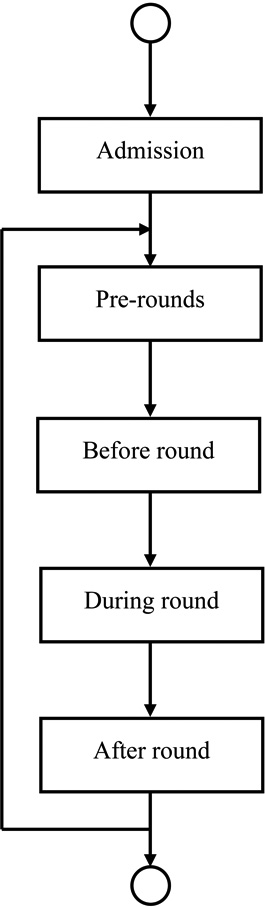

This study was conducted on one hematology/oncology service and one hospitalist service at the children’s hospital. The PE process included various activities (see Figure 1): (1) formation and meetings of the “Intervention Implementation Team” (IIT), (2) data collection activities, (3) development of the intervention, and (4) implementation of the intervention. In sections 3.1 to 3.4, we describe each activity and their associated results.

Figure 1.

Timeline of the PE Process.

3.1 Intervention Implementation Team (IIT)

FCR stakeholders were involved in the PE process through “direct representative participation” within a three-layer embedded structure (Haines et al. 2002). An IIT (layer 1) was formed to support the PE process, consisting of five researchers (four HFE professionals and one pediatric hospitalist attending physician) and ten representative FCR stakeholders from the hospital:

One parent from the hospital’s family advisory council,

A medical administrator,

Two nurse managers,

Two nurses,

Two attending physicians,

Two senior resident physicians.

The IIT was responsible for: (1) designing an intervention to improve family engagement in the FCR process, (2) creating an implementation plan for the intervention, and (3) championing the implementation of the intervention. Six IIT meetings were held over a 10-month period (see Figure 1). Table 1 summarizes the participants, activities and outcomes of each meeting.

Table 1.

Summary of IIT meetings.

| Timeline | Participants | Activities | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meeting 1 (Jan. 2012) |

|

|

|

| Meeting 2 (Mar. 2012) |

|

|

|

| Meeting 3 (Apr. 2012) |

|

|

|

| Meeting 4 (May 2012) |

|

|

|

| Meeting 5 (Jul. 2012) |

|

|

|

| Meeting 6 (Oct. 2012) |

|

|

At each IIT meeting, two researchers (the physician and one of the HFE professionals) facilitated the discussion, while the other three researchers recorded meeting notes and managed the logistics of the meeting. Researchers carried out decisions made by the IIT in between meetings and met regularly with the steering committee of the overall research project to report progress and gather feedback from stakeholders (layer 2). Stakeholder representatives on the IIT were expected to actively participate in the meetings and communicate with their colleagues in between meetings to bring a broader perspective to the IIT (Xie et al. 2014). FCR stakeholders who did not participate in the IIT (layer 3) were also able to voice their opinions and contribute to the redesign process through various mechanisms, e.g., interviews (Carayon et al. 2011; Carayon, Li, et al. 2014; Kelly et al. 2013), surveys (Xie et al. 2012) and the pilot study of the intervention (Li et al. 2013) (see sections 3.2 and 3.4). Details of FCR stakeholder collaboration in the PE process are described by Xie et al. (2014).

3.2 Data collection activities

Before and in between IIT meetings, researchers collected various types of data that were used as input to facilitate discussion during IIT meetings and to inform the development of the intervention. These data included:

Observation of the FCR process,

Stimulated recall interviews with FCR stakeholders,

Two surveys on (1) the impact of 21 strategies for improving family engagement in FCR and (2) the feasibility and sustainability of 3 intervention ideas selected for possible implementation.

3.2.1 Observation of the FCR process

Using the HFE work system model (Carayon 2009; Carayon and Smith 2000; Smith and Carayon 2000; Smith and Carayon-Sainfort 1989) and the SEIPS model (Carayon et al. 2006; Carayon, Wetterneck, et al. 2014), researchers on the IIT conducted more than 60 hours of observation of the FCR process on different services (i.e., hematology/oncology, hospitalist). The observations allowed researchers to become familiar with the FCR process and identify the various work system elements involved in the process. A map of the FCR process was produced, which included different stages of the FCR process and described work system elements (e.g., people, tasks, tools and technologies, organization, environment) associated with each process stage (see Table 2). The FCR process was divided in five stages: admission, pre-rounds, before round, during round, and after round. The rounding session in the FCR process begins when the healthcare team arrives at the patient room and greets the patient and/or family, and ends when the team moves on to the next patient. Activities before and after the rounding session could impact family engagement in FCR. For example, resident physicians conduct pre-rounds in the early morning to collect information used by the rest of the healthcare team when talking to the patient and family during round. However, the focus of the PE redesign project was on the rounding session.

Table 2.

Process map of the FCR process.

|

Who | Tasks of family | Tasks of healthcare team | Environment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.2.2 Stimulated recall interviews

Semi-structured interviews using the HFE stimulated recall approach1 were conducted with different FCR stakeholders, including 4 patients, 11 families and 22 healthcare team members (8 attending physicians, 6 resident physicians, 5 medical students, 3 nurses), to identify work system facilitators and barriers to family engagement in FCR, as well as strategies for improving family engagement in FCR. Details of the stimulated recall interviews can be found in Kelly et al. (2013) and Carayon, Li, et al. (2014). Work system facilitators and barriers to family engagement in FCR have been reported by Carayon et al. (2011). Strategies for improving family engagement in FCR were sorted into 21 categories related to the work system and process of FCR, and have been reported by Kelly et al. (2013).

3.2.3 Surveys

A survey2 was conducted with 134 FCR stakeholders (28 families, 31 nurses, 55 attending and resident physicians, and 20 medical students) to evaluate their perceptions of the potential impact of identified FCR strategies on family engagement. Details of the survey can be found in Xie et al. (2012). IIT members reviewed impact survey data during the first meeting (see Table 1), and categorized strategies into three groups: (1) should be addressed by the intervention, (2) might be addressed by the intervention, and (3) should not be addressed by the intervention. IIT members then brainstormed ideas for the intervention by focusing on strategies in the group of “should be addressed by the intervention”.

After the first meeting, researchers summarized proposed intervention ideas in three “big picture” ideas: (1) scheduling rounds, (2) family preference system for rounds and (3) best practices for rounds. A second survey3 was conducted with 82 FCR stakeholders (14 families, 13 nurses, 43 attending and resident physicians, and 12 medical students) to evaluate the feasibility and sustainability of these intervention ideas at the children’s hospital. IIT members reviewed feasibility survey data in the second meeting (see Table 1), and made a group decision to design and implement a FCR checklist of best practices for performing rounds and a family preference system asking families beforehand for their preferences for rounds. The idea of scheduling rounds was perceived to be less feasible by the survey participants and by the physicians on the IIT and, therefore, no longer considered.

3.3 Development of the intervention

After the second IIT meeting, researchers conducted additional observations to understand how a FCR checklist (i.e. the main element of the intervention) could fit in the current workflow. HFE literature on checklist design and implementation was reviewed (see Appendix A) and presented to IIT members in the third meeting (see Table 1). The IIT discussed details about the FCR checklist, including:

The content, such as tasks that should be done and the order of items on the FCR checklist;

The format, such as paper vs. laminated paper vs. electronic, dimensions, color and font size;

Roles related to the checklist, such as who will complete each task on the checklist and who is the “checklist holder”;

The workflow associated with the checklist, such as where, when and how checklist items would be done.

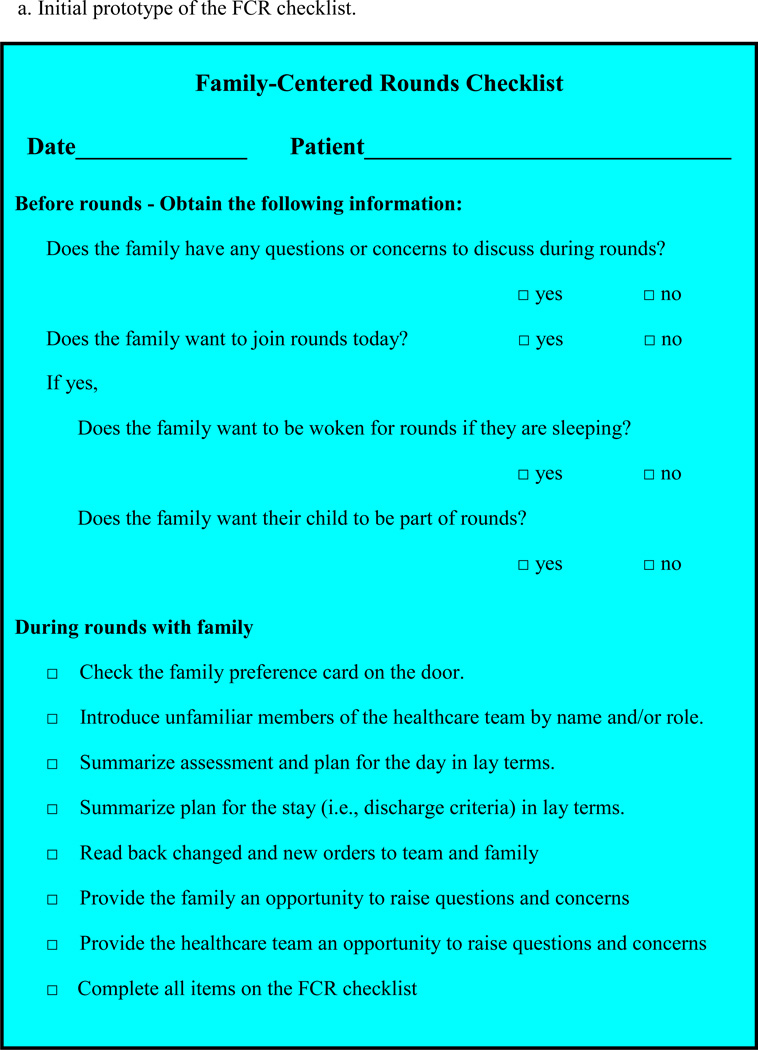

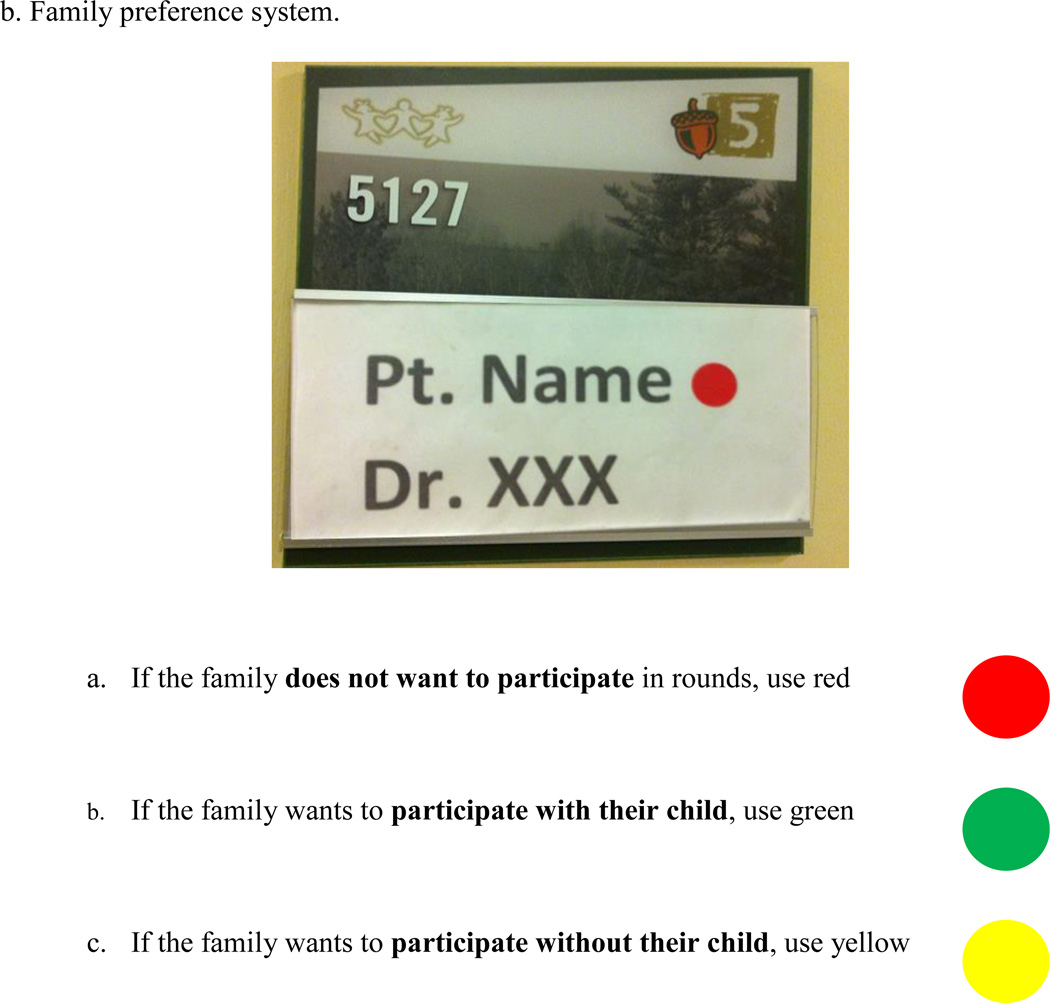

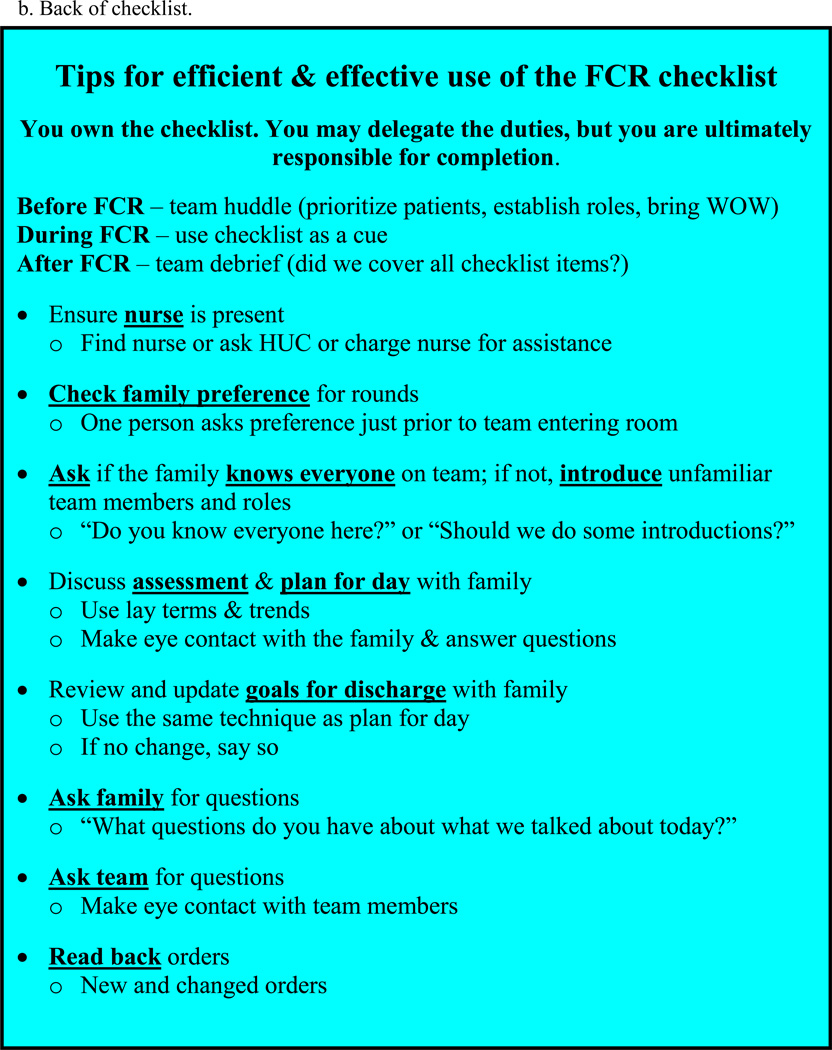

One IIT member shared her experience with the family preference system developed at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital (Muething et al. 2007). After the third meeting, researchers talked with a nurse manager at Cincinnati Children's Hospital about the design and implementation of their family preference system. Researchers then created an initial prototype of the FCR checklist, which consisted of a “before-rounds checklist” and a “during-rounds checklist” (see Figure 2a). The before-round checklist was then adapted for a family preference system (see Figure 2b), and the FCR checklist was revised accordingly. For each newly admitted patient, the nurse was responsible for asking the family for their preference for rounds and placing the corresponding colored sticker on the nameplate outside of the patient’s room. During each rounding session, the holder of the FCR checklist4 was responsible for ensuring healthcare team members performed all items on the checklist and checking off items on the FCR checklist. The attending physician was expected to remind healthcare team members to perform the checklist items if missed by the checklist holder.

Figure 2.

Initial design of the FCR intervention.

3.4 Implementation of the intervention

In the phase of intervention implementation, three IIT meetings helped develop the implementation plan and address implementation challenges (see Table 1). The plan included a pilot study and training and information sessions.

3.4.1 Pilot study

A pilot study of the FCR checklist and the family preference system was conducted to refine the intervention and to identify facilitators and barriers to its use (Li et al. 2013). First, the FCR checklist and family preference system were trialed on the hospitalist service for one week with the hospitalist physician researcher on the IIT. We found that, although the family preference system was intended to inform the healthcare team as to whether and how the family would like to participate in rounds, this system had several limitations: (1) healthcare team members were not used to checking the nameplate prior to each rounding session, (2) family preferences for rounds might change from day to day, and (3) the family would be caught off guard when an entire team enter the patient room at once, even if they had indicated their preference for rounds on admission. Therefore, the healthcare team still needed to check family preference right before rounding with each patient. Results of the pilot study were presented to IIT members during the fifth meeting (see Table 1), and the IIT decided to replace the family preference system by adding the item “check family preference for rounds” to the FCR checklist.

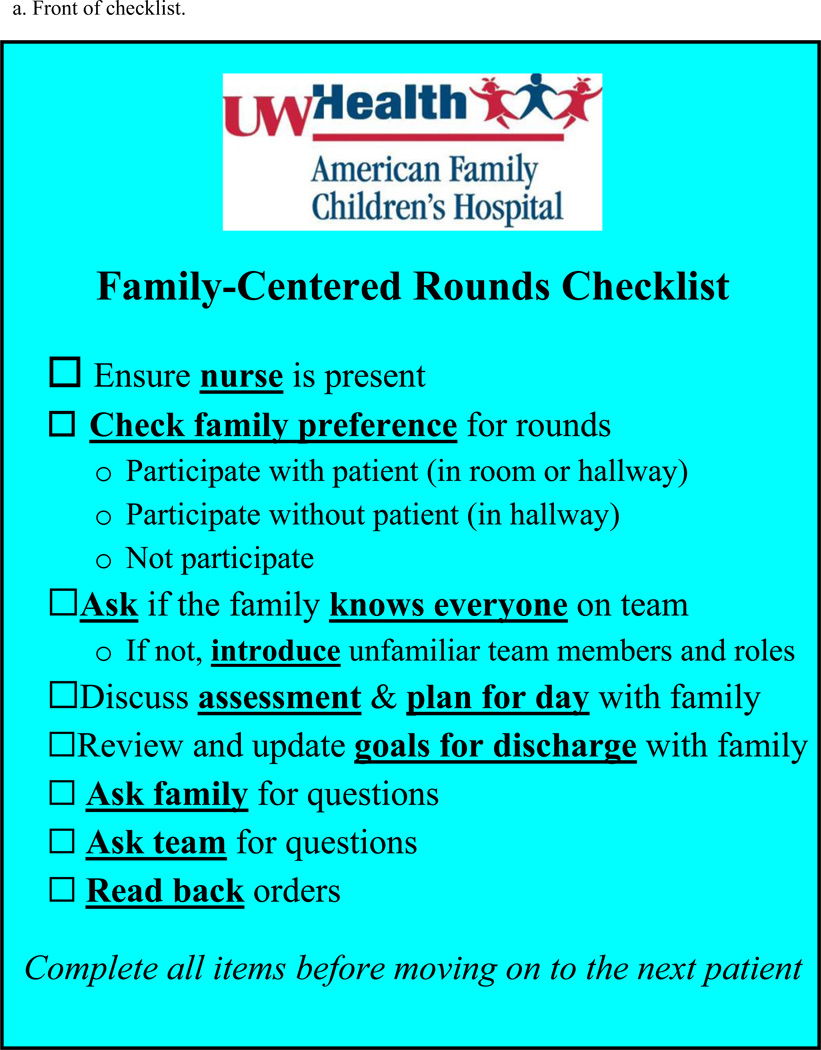

The revised FCR checklist with the integration of family preference was subsequently trialed on the hematology/oncology service with one attending physician who was also an IIT member. The trial lasted for another week, and a similar process was followed for revision, which included the following changes:

Adding the item “ensure nurse is present” to encourage nursing participation on rounds;

Revising items to be more precise and clinically meaningful;

Revising the order of items to adapt the checklist to the workflow of rounds;

Increasing the font size and using bold to highlight key points of each item;

Replacing the item “complete all items before moving on” with a similar reminder at the bottom of the checklist.

The final version of the FCR checklist (see Figure 3a) was trialed on the hospitalist service with the other attending hospitalist on the IIT. This took one more week, and tips for using the FCR checklist were added to the back of the checklist (see Figure 3b) to remind healthcare team members how each checklist item should be performed.

Figure 3.

Final version of the FCR checklist.

During the pilot study, work system factors influencing FCR checklist use were identified (see Table 3 for examples); and solutions were developed to facilitate the use of the FCR checklist. For example, checklist holders found it challenging to check off each item on the FCR checklist for every patient as they had plenty to do on rounds. Therefore, the FCR checklist was laminated and used only as a visual cue. We used different methods to ensure that the FCR checklist was visible on different services. On the hematology/oncology service, we attached the FCR checklist to the moving table that the fellow or attending physician always brought on rounds. The hospitalist team did not use a table on rounds; therefore, the FCR checklist was attached to a tablet computer that the senior resident physician brought on rounds. Further, to complete the FCR checklist item regarding “reading back orders”, the healthcare team needed to enter orders during rounds using a workstation on wheels (WOW). The hospitalist team did not have access to a WOW in all patient locations; so the hospital medical director who was also on the IIT helped ensure that a WOW was available on all units for the hospitalist team.

Table 3.

Work system factors influencing FCR checklist use during pilot study.

| Work system elements | Factors influencing FCR checklist use |

|---|---|

| People | + Healthcare team members being familiar with checklist items |

| Tools and technologies | + FCR checklist being visible on rounds − Not bringing the moving table or the tablet computer on rounds − Not bringing the WOW on rounds |

| Tasks | + Huddle before rounds and debriefing after rounds − Large number of patients to round − Multiple tasks on rounds |

| Organization | + Clearly defined role and responsibility of healthcare team members − Team rounding with different specialists − Early in rotation for senior resident/fellow physician |

| Environment | − Moving WOW to different locations − Patients in isolation − Interruptions |

+ Facilitators, − Barriers

3.4.2 Training and information sessions

All attending and senior resident physicians on the hospitalist service and attending and fellow physicians on the hematology/oncology service participated in training sessions about the FCR checklist. Training materials were created by researchers on the IIT and reviewed and revised by other IIT members. The 90-minute training session consisted of a 60-minute didactic presentation and a 30-minute role-play simulation. The didactic presentation included an introduction to FCR, a brief description of the overall research project, and a detailed explanation of the FCR checklist and how each item on the FCR checklist should be performed. The role-play simulation included two rounding scenarios in which participants played in turn the roles of attending physician, fellow/senior resident physician, intern and parent/patient to practice the use of the checklist.

In addition to the training, six 20-minute informational sessions were held with other FCR stakeholder groups who might be affected by the FCR checklist, such as subspecialty physician groups, pharmacists, nurses, and other residents, to inform them of the imminent implementation of the FCR checklist.

4. Evaluation of the PE Process

In this section, we present data on the evaluation of the PE process, including survey data on participants’ perceptions of IIT meetings and training sessions, as well as pilot study data on FCR checklist use.

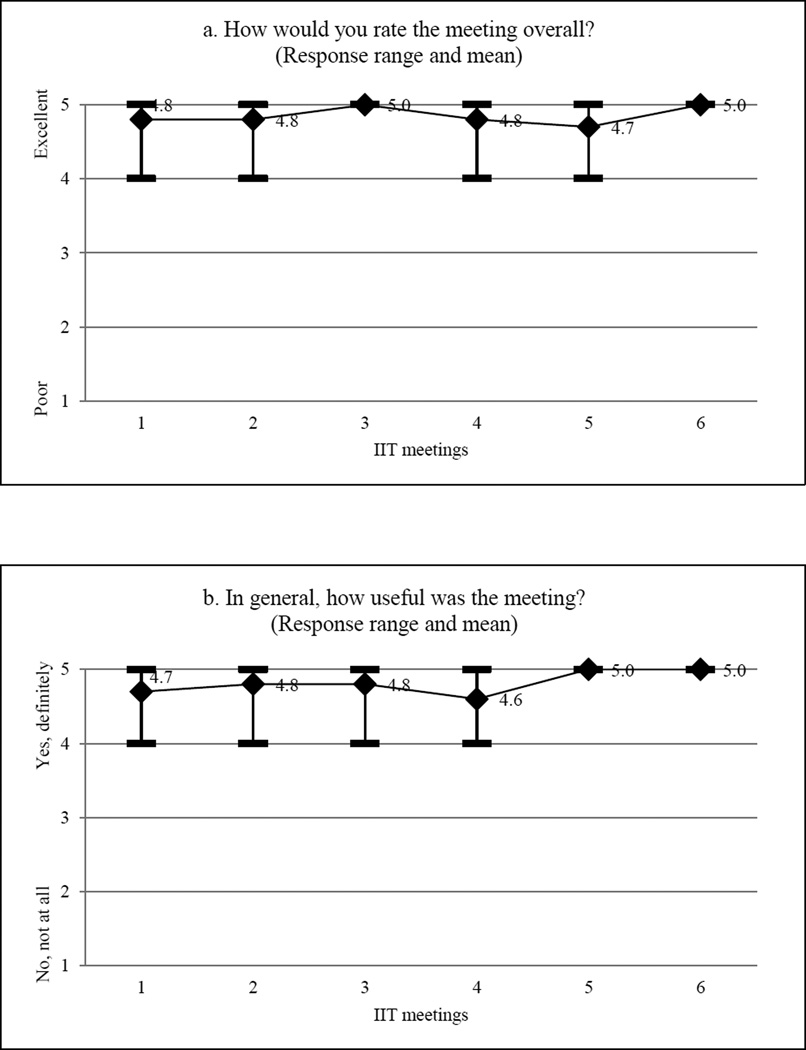

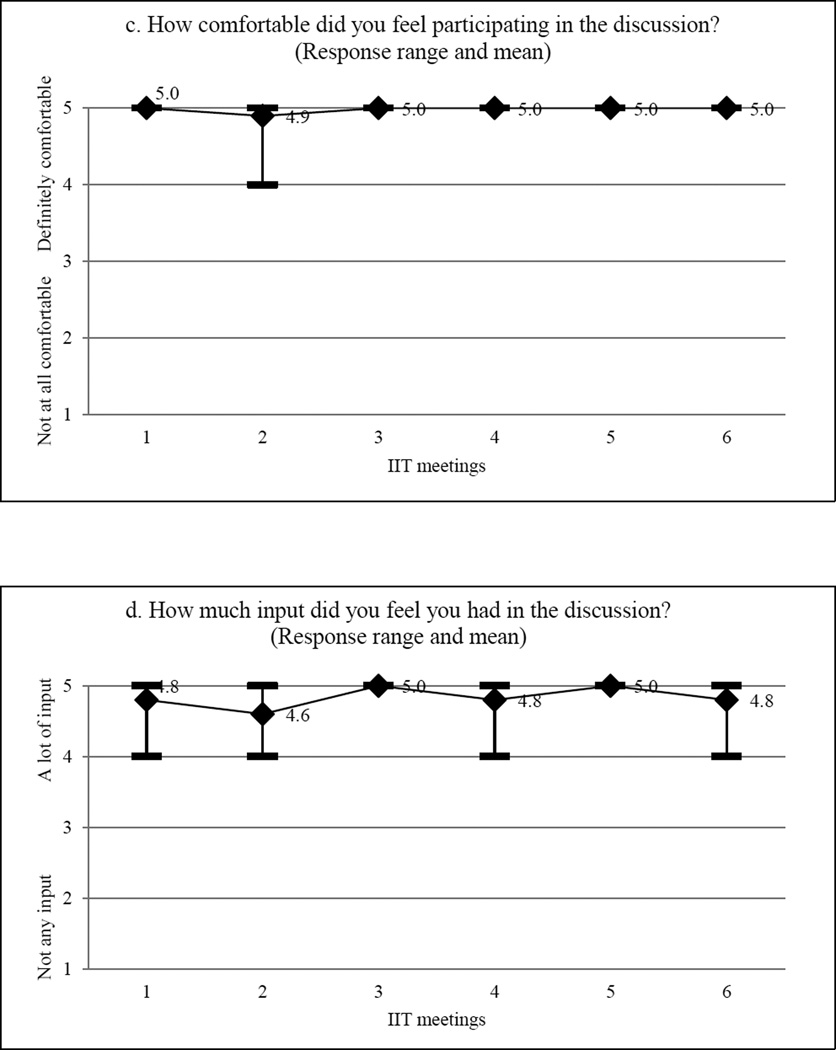

4.1 Evaluation of IIT meetings

IIT members provided feedback about the PE process through short surveys that were completed at the end of each meeting. The surveys included five questions with response categories on a 5-point Likert scale: (1) “How would you rate the meeting overall?” (1=poor, 5=excellent); (2) “In general, how useful was the meeting?” (1=not at all useful, 5=definitely useful); (3) “How comfortable did you feel participating in the discussion?” (1=not at all comfortable, 5=definitely comfortable); (4) “How much input did you feel you had in the discussion?” (1=not any input, 5=a lot of input); and (5) “To what extent was the content presented clearly?” (1=not at all clearly, 5=definitely clearly). At the end of the survey, we encouraged participants to provide comments or suggestions about their meeting experience by asking them, “What do you like most/least about the IIT meeting?”, “What challenges do you face or anticipate in actively participating in the IIT?”, and “What should be done to improve the next IIT meeting?”.

The PE process involved 6 IIT meetings for a total of 16 hours over a 10-month period: the first two meetings were 4 hours long, while the other four meetings lasted 2 hours each. Out of the 10 stakeholder representatives, 8 participated in the first three IIT meetings, 7 participated in the fourth and sixth meetings, and only 4 participated in the fifth meeting. Survey data showed a consistently high level of satisfaction with the meetings (see Figure 4). In addition, participants provided several suggestions to improve the PE process that were implemented subsequently, such as shortening the duration of meetings from 4 to 2 hours, clarifying the goal of each meeting, sending meeting materials to participants before each meeting, and keeping participants posted on progress.

Figure 4.

Evaluation of IIT meetings.

4.2 Evaluation of training

Training participants filled out a short survey at the end of the training sessions. The survey included three questions with response categories on a 5-point Likert scale: (1) “How would you rate the training overall?” (1=poor, 5=excellent); (2) “How applicable is the training to your everyday inpatient practice?” (1=not at all applicable, 5=definitely applicable); and (3) “How likely are you to use the FCR checklist?” (1=very unlikely, 5=very likely).

Training on the use of the FCR checklist was provided to 13 attending physicians, 9 senior resident physicians and 3 fellow physicians. In general, the training was well received as demonstrated by results of the evaluation form filled out by 22 of the 25 participants:

16 (73%) said that the training was excellent;

17 (77%) said that the training was “definitely applicable” to their everyday inpatient practice;

20 (91%) said that they were “very likely” to use the FCR checklist during rounds.

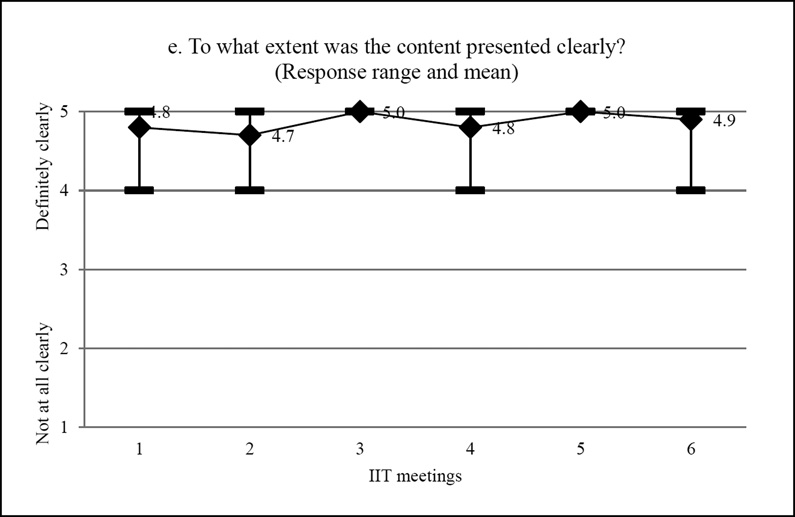

4.3 Evaluation of FCR checklist use during the pilot study

During the pilot study, HFE researchers on the IIT observed healthcare teams performing FCR and evaluated the use of the FCR checklist. During each observation period, which was defined as a rounding session for a single patient, the following information was captured for each checklist activity: (1) the order in which the activity is performed; (2) whether the activity is performed; (3) who performs the activity; (4) whether anyone reminds the healthcare team to perform the activity; and (5) who reminds the healthcare team to perform the activity. After daily FCR, if possible, the observer interviewed healthcare team members (e.g., attending physician, senior resident physician, fellow physician, intern, nurse) to understand their experience with the FCR checklist.

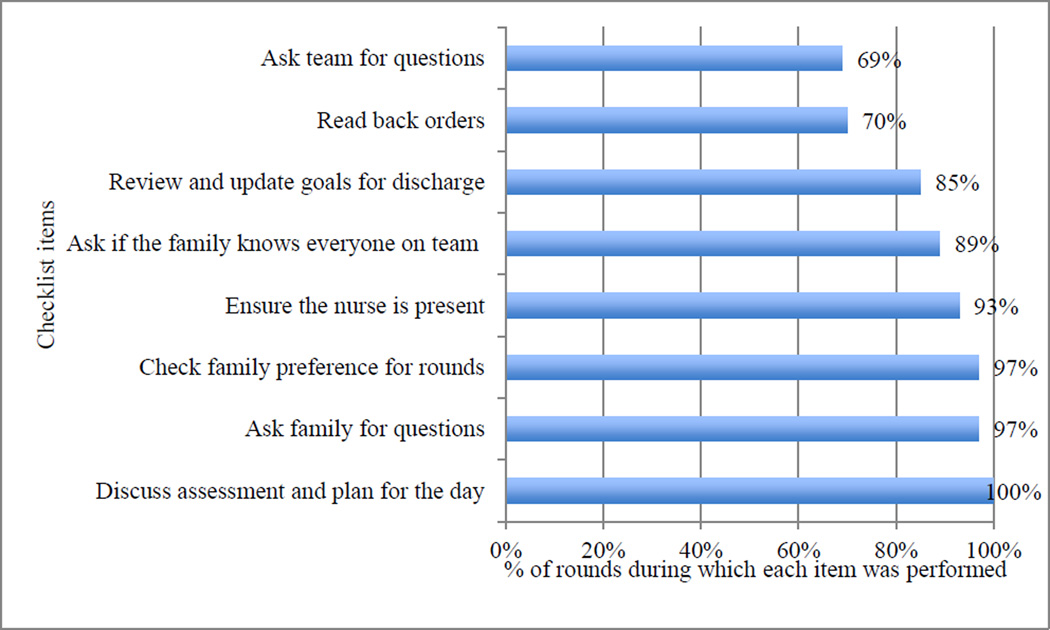

A total of 47 rounds were observed during the pilot study: 36 on the hospitalist service, and 11 on the hematology/oncology service. Figure 5 shows the percentage of rounds on which each checklist item was performed. Observation data indicated that checklist items were not done consistently, while healthcare team members mentioned in the interviews that they did all items of the checklist. Therefore, tips for using the FCR checklist were added to the back of the checklist (see section 3.4.1) and training was provided to healthcare team members (see section 3.4.2) to emphasize how each checklist item should be performed.

Figure 5.

FCR checklist use during pilot study (N=47 rounds).

5. Discussion

We describe how a PE approach can be applied to redesign the FCR process in order to improve family engagement. This study broadens the application of PE from designing individual tasks and addressing physical ergonomic issues (e.g., musculoskeletal disorders of nurses performing patient handling tasks) (Bohr, Evanoff and Wolf 1997; Fragala and Santamaria 1997; Udo et al. 2006) to the design of complex healthcare processes that address cognitive (e.g., shared mental model, cognitive workload) and organizational (e.g., teamwork, collaboration) HFE issues. While our study was performed in the context of a research study, PE is an approach that can be used outside of the research setting by ergonomics professionals and healthcare stakeholders as well.

5.1 Participation of different FCR stakeholders

Different FCR stakeholders were involved in the PE process, including patients and families, attending and resident physicians, nurses, and hospital management. They were able to voice their opinions and contribute to the redesign in different ways, such as involvement in the IIT and participation in interviews and surveys. A critical issue related to the participation of different stakeholders was their collaboration, through which they could establish a common ground and clarify and integrate their perspectives (Détienne 2006). For example, nurses and families thought that introducing the healthcare team and the family to each other at the beginning of rounds would improve family engagement in FCR, while physicians worried about the impact of long introductions on rounding efficiency (Xie et al. 2012). IIT members discussed these different perspectives, and ultimately agreed on keeping introduction as a best practice for rounds on the FCR checklist but providing healthcare team members the autonomy to perform it in their own ways (e.g., introducing everyone vs. unfamiliar members on the team, introducing name vs. role).

As part of the overall research project, we interviewed the 10 stakeholder representatives on the IIT to understand how they collaborated through the PE process (Xie et al. 2014). A model of collaborative healthcare system redesign was developed, which extends the collaborative redesign process beyond collaboration during meetings and emphasizes the elements of team setup and meeting preparation and follow-up. Challenges to multi-stakeholder collaboration in healthcare system redesign were identified, such as representing all relevant stakeholders, scheduling of meetings, and managing different perspectives.

5.2 Integration of HFE in the content and process of FCR redesign

In this study of PE, HFE was integrated in both the content and process of FCR redesign. The content of FCR redesign (intervention) was developed according to the following HFE design principles: shared mental model, usability, workload consideration, and systems approach; see Table 4 for specific activities aligned with the HFE design principles. The FCR checklist (content of intervention) was designed to facilitate communication and the development of a shared mental model among healthcare team members, patients and families. To optimize its usability, the content and format of the FCR checklist were designed according to HFE literature (see Appendix A), and prototypes of the FCR checklist were developed, trialed and revised. To avoid adding workload to already busy healthcare team members, we assigned specific individuals to the role of checklist holder and asked them to use the FCR checklist as a visual cue, instead of checking off checklist items for every patient. The FCR checklist was also adapted to different services (e.g., hospitalist, hematology/oncology) with changes of work system elements to facilitate its use. For instance, in the hematology/oncology service, the FCR checklist was stored in the physician workroom and attached to the table used during rounds.

Table 4.

HFE in the content of FCR redesign.

| HFE design principles |

Description | Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Shared mental model | Knowledge structure held by members of a team that enables them to form accurate explanations and expectations for the task, and in turn, to coordinate their actions and adapt their behavior to demands of the task and other team members (Cannon-Bowers, Salas and Converse 1993) |

|

| Usability | Extent to which a product can be used by specified users to achieve specified goals with effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction in a specified context of use (ISO 9241-11 1998) |

|

| Workload consideration | Avoiding dysfunctional mental workload and providing for optimal mental workload which will avoid impairing effects and promote facilitating effects and the personal development of the worker (ISO 10075-2 1996) |

|

| Systems approach | Considering interactions among work system elements and levels (Carayon et al. 2006; Waterson 2009; Wilson 2000) |

|

| Considering context and dynamic impact of individual work system elements on the whole system (Carayon et al. 2006; Waterson 2009; Wilson 2000) |

|

|

| Considering linkage between work system, care processes and system outcomes (Carayon et al. 2006; Waterson 2009; Wilson 2000) |

|

The overall PE process of FCR redesign was guided by the following HFE implementation principles: top management commitment, stakeholder participation, communication and feedback, learning and training, and project management (Carayon, Alyousef and Xie 2012; Karsh 2004; Smith and Carayon 1995). Table 5 provides a list of activities that correspond to each of the HFE implementation principles.

Table 5.

HFE in the process of FCR redesign.

| HFE Implementation Principles |

Description | Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Top management commitment | Extent to which top management directly participate in healthcare system redesign (Carayon, Alyousef and Xie 2012) |

|

| Stakeholder participation | Extent to which healthcare professionals, patients and families are involved in various decisions and activities related to healthcare system redesign (Carayon, Alyousef and Xie 2012) |

|

| Communication and feedback | Extent to which healthcare professionals, patient and families are kept informed of healthcare system redesign and extent to which feedback is sought during/after healthcare system redesign (Carayon, Alyousef and Xie 2012) |

|

| Learning and training | Extent and nature of training provided to healthcare professionals, patients and families and extent of their learning (Carayon, Alyousef and Xie 2012) |

|

| Project management | Activities related to organization and management of healthcare system redesign (Carayon, Alyousef and Xie 2012) |

|

5.3 Challenges to the PE process

Some challenges and practical issues of PE to redesign complex healthcare processes were identified. A balance between structure and flexibility was important to the PE process (Haims and Carayon 1998). Preparation was necessary to keep the PE process on track. A charter was created to clearly define the objectives, participants, timeline and work plan of the PE process.5 On the other hand, the PE process was adjusted according to the needs of stakeholder representatives. For example, based on feedback from stakeholder representatives (see data on evaluation of IIT meetings), the duration of meetings was reduced from four hours to two hours.

Commitment of time and effort from stakeholder representatives and all levels of the organization was also important to the PE process (Haims and Carayon 1998; Wilson, Haines and Morris 2005). To gain both buy-in from the front line and support from management, the IIT involved people representing patients and families, healthcare team members and hospital management. These stakeholder representatives were expected to devote a total of sixteen hours to participate in the IIT meetings, as well as additional time communicating with their colleagues in between IIT meetings as needed. Scheduling of meetings with stakeholder representatives was challenging. Only 2 of the 10 stakeholder representatives attended all 6 IIT meetings; none of the IIT meetings had all stakeholder representatives present. To allow more stakeholders to attend, the IIT meetings were scheduled far enough ahead of time, and meeting materials were provided in advance.

5.4 Study Limitations

This study was conducted at a single academic children’s hospital, which limits the generalizability of the results to other settings. In the context of this large research project, HFE researchers were highly involved in the study to organize the PE process. Researchers spent a considerable amount of time on preparing, organizing and facilitating the PE process. Much of this work went into the many modes of data collection that were used for the study (e.g. observation, interviews, surveys) which can be scaled up or down depending on an organization’s resources to collect data outside of a research setting. Other healthcare organizations need to consider how to integrate PE in their quality improvement projects without the involvement of HFE researchers. For example, an organization may train quality improvement personnel in HFE and ask them to initiate and guide a PE process.

6. Conclusion

PE can be used to promote the participation of healthcare stakeholders in and the application of HFE to healthcare system redesign. We applied PE to redesign the FCR process on two services at a children’s hospital. The next step is to evaluate the FCR checklist use after implementation, as well as the impact of the redesign on the FCR process (e.g., family engagement, efficiency of rounds) and possibly patient outcomes (e.g., patient satisfaction) (Xie and Carayon 2014). In addition to the research project, the children’s hospital is planning to continuously improve the FCR process and disseminate the FCR checklist across inpatient services. This requires the progression of the PE program from external to internal regulation (Haims and Carayon 1998).

Practitioner Summary.

The application of participatory ergonomics (PE) to healthcare system redesign is limited. This study broadens PE application from designing individual tasks in specific jobs to address physical ergonomic issues to designing complex healthcare processes to address cognitive and organizational ergonomic issues.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by an AHRQ Health Services Research Demonstration and Dissemination grant, R18 HS018680 (Cox, PI), and the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, previously through the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) grant 1UL1RR025011, and now by the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) grant 9U54TR000021. The authors would like to thank Betty Chewning, Michael J. Smith and Douglas A. Wiegmann for their comments and feedback.

Appendix A. Overview of HFE research on checklist

| Topics | HFE Principles | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Checklist design |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Checklist implementation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Footnotes

This method is called confrontation in the French HFE literature (Faye and Falzon 2009; Mollo and Falzon 2004).

Available at: http://cqpi.wisc.edu/pediatric-family-centered-rounds.htm

Available at: http://cqpi.wisc.edu/pediatric-family-centered-rounds.htm

The hospitalist and hematology/oncology services had different team structures. The senior resident on the hospitalist team and the fellow physician on the hematology/oncology team were assigned to be the holder of the FCR checklist.

Available at: http://cqpi.wisc.edu/pediatric-family-centered-rounds.htm

References

- Andersen LL, Zebis MK. Process evaluation of workplace interventions with physical exercise to reduce musculoskeletal disorders. International Journal of Rheumatology. 2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/761363. 2014, 11 pages. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohr PC, Evanoff BA, Wolf L. Implementing participatory ergonomics teams among health care workers. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 1997;32(3):190–196. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0274(199709)32:3<190::aid-ajim2>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon-Bowers JA, Salas E, Converse S. Shared mental models in expert team decision making. In: Castellan NJ, editor. Individual and group decision making: Current issues. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1993. pp. 221–246. [Google Scholar]

- Carayon P. The balance theory and the work system model … Twenty years later. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction. 2009;25(5):313–327. [Google Scholar]

- Carayon P. Human factors in patient safety as an innovation. Applied Ergonomics. 2010;41(5):657–665. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carayon P. Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics in Health Care and Patient Safety. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Carayon P, Alvarado CJ, Hundt AS. Work design and patient safety. Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science. 2007;8(5):395–428. [Google Scholar]

- Carayon P, Alyousef B, Xie A. Human factors and ergonomics in health care. In: Salvendy G, editor. Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics. 4th ed. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons; 2012. pp. 1574–1595. [Google Scholar]

- Carayon P, Dubenske LL, Mccabe BC, Shaw B, Gaines ME, Kelly MM, Orne J, Cox ED. Work system barriers and facilitators to family engagement in rounds in a pediatric hospital. In: Albolino S, Bagnara S, Bellandi T, Llaneza J, Rosal-Lopez G, Tartaglia R, editors. Healthcare Systems Ergonomics and Patient Safety 2011: Proceedings on the International Conference on Healthcare Systems Ergonomics and Patient Safety (HEPS 2011) Oviedo, Spain: CRC Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Carayon P, Hundt AS, Karsh B-T, Gurses AP, Alvarado CJ, Smith M, Brennan PF. Work system design for patient safety: the SEIPS model. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2006;15(Supplement I):i50–i58. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.015842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carayon P, Li Y, Kelly MM, Dubenske LL, Xie A, Mccabe BC, Orne J, Cox ED. Stimulated recall methodology for assessing work system barriers and facilitators in family-centered rounds in a pediatric hospital. Applied Ergonomics. 2014;45(6):1540–1546. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carayon P, Smith MJ. Work organization and ergonomics. Applied Ergonomics. 2000;31:649–662. doi: 10.1016/s0003-6870(00)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carayon P, Wetterneck TB, Rivera-Rodriguez AJ, Hundt AS, Hoonakker P, Holden R, Gurses AP. Human factors systems approach to healthcare quality and patient safety. Applied Ergonomics. 2014;45(1):14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2013.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carayon P, Xie A. Decision making in healthcare system design: when human factors engineering meets health care. In: Proctor RW, Nof SY, Yih Y, editors. Cultural Factors in Systems Design: Decision Making and Action. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Hospital Care and Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care. Patient- and family-centered care and the pediatrician's role. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):394–404. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committtee on Drugs and Committee on Hospital Care. Prevention of medication errors in the pediatric inpatient setting. Pediatrics. 2003;112(2):431–436. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.2.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong AM, Vink P. The adoption of technological innovations for glaziers; evaluation of a participatory ergonomics approach. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics. 2000;26(1):39–46. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong AM, Vink P. Participatory ergonomics applied in installation work. Applied Ergonomics. 2002;33(5):439–448. doi: 10.1016/s0003-6870(02)00033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Looze MP, Urlings IJM, Vink P, Van Rhijn JW, Miedema MC, Bronkhorst RE, Van Der Grinten MP. Towards successful physical stress reducing products: an evaluation of seven cases. Applied Ergonomics. 2001;32(5):525–534. doi: 10.1016/s0003-6870(01)00018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degani A, Wiener EL. Cockpit checklists: concepts, design, and use. Human Factors. 1993;35(2):345–359. [Google Scholar]

- Détienne F. Collaborative design: managing task interdependencies and multiple perspectives. Interacting with Computers. 2006;18(1):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1988;260(12):1743–1748. doi: 10.1001/jama.260.12.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlak JA, Dupre EP. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3–4):327–350. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endsley MR. An implementation model for reducing resistance to technological change. International Journal of Human Factors in Manufacturing. 1994;4(1):65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Evanoff VA, Bohr PC, Wolf L. Effects of a participatory ergonomics team among hospital orderlies. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 1999;35:358–365. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0274(199904)35:4<358::aid-ajim6>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans LV, Dodge KL. Simulation and patient safety: evaluative checklists for central venous catheter insertion. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2010;19(Suppl 3):i42–i46. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2010.042168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faye H, Falzon P. Strategies of performance self-monitoring in automotive production. Applied Ergonomics. 2009;40(5):915–921. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fragala G, Santamaria D. Heavy duties? Health Facilities Management. 1997;10(5) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin SF, Wilcox S, Ory MG, Lattimore D, Leviton L, Castro C, Carpenter RA, Rheaume C. Results from the Active for Life process evaluation: program delivery fidelity and adaptations. Health Educ Res. 2010;25(2):325–342. doi: 10.1093/her/cyp017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haims MC, Carayon P. Theory and practice for the implementation of 'in-house', continuous improvement participatory ergonomic programs. Applied Ergonomics. 1998;29(6):461–472. doi: 10.1016/s0003-6870(98)00012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines H, Wilson JR. Development of a Framework for Participatory Ergonomics. Norwich, UK: Health and Safety Executive; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Haines H, Wilson JR, Vink P, Koningsveld E. Validating a framework for participatory ergonomics (the PEF) Ergonomics. 2002;45(4):309–327. doi: 10.1080/00140130210123516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hales B, Terblanche M, Fowler R, Sibbald W. Development of medical checklists for improved quality of patient care. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2008;20(1):22–30. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CA, Dawson KD. Design and implementation of a participatory ergonomics program for machine sewing tasks. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics. 1997;20(6):429–440. [Google Scholar]

- Herring R, Desai T, Caldwell G. Quality and safety at the point of care: how long should a ward round take? Clinical Medicine. 2011;11(1):20–22. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.11-1-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iso 9241-11. Ergonomics requirements for office work with visual display terminals (VDTs) -- Part 11: Guidance on usability. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- Iso 10075-2. Ergonomic principles related to work-load -- Design principles. 1996 [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan G, Bo-Linn G, Carayon P, Pronovost P, Rouse W, Reid PR, Saunders R. Bringing a systems approach to health, Discussion Paper, Institute of Medicine and National Academy of Engineering, Washington, DC. 2013 http://www.iom.edu/systemsapproaches.

- Karsh B-T. Beyond usability: designing effective technology implementation systems to promote patient safety. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2004;13(5):388–394. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.010322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal R, Bates DW, Landrigan C, Mckenna KJ, Clapp MD, Federico F, Goldmann DA. Medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285(16):2114–2120. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.16.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MM, Xie A, Carayon P, Dubenske LL, Ehlenbach ML, Cox ED. Strategies for improving family engagement during family-centered rounds. Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2013;8(4):201–207. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laitinen H, Saari J, Kuusela J. Initiating an innovative change process for improved working conditions and ergonomics with participation and performance feedback: a case study in an engineering workshop. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics. 1997;19(4):299–305. [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Carayon P, Xie A, Kelly MM, Cartmill R, Cox ED. 2013 Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Symposium on Human Factors and Ergonomics in Health Care. Baltimore, MD: 2013. Work system challenges to implementing a family-centered rounds checklist. [Google Scholar]

- Liker JK, Nagamachi M, Lifshitz YR. A comparative analysis of participatory ergonomics programs in U.S. and Japan manufacturing plants. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics. 1989;3(3):185–199. [Google Scholar]

- Lingard L, Espin S, Rubin B, Whyte S, Colmenares M, Baker GR, Doran D, et al. Getting teams to talk: development and pilot implementation of a checklist to promote interprofessional communication in the OR. Quality and Safety in Health Care. 2005;14(5):340–346. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.012377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingard L, Regehr G, Orser B, Reznick R, Baker GR, Doran D, Espin S, Bohnen J, Whyte S. Evaluation of a preoperative checklist and team briefing among surgeons, nurses, and anesthesiologists to reduce failures in communication. Archives of Surgery. 2008;143(1):12–17. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2007.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnan L, Steckler A. Process evaluation fro public health interventions and research: an overview. In: Steckler A, Linnan L, editors. Process Evaluation for Public Health Interventions and Research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan RP. The WHO surgical checklist. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2011.02.002. (1521-6896 (Print)) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield JA, Armstrong TJ. Library of congress workplace ergonomics program. American Industrial Hygeine Association Journal. 1997;58(2):138–144. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal VS, Sigrest T, Ottolini MC, Rauch D, Lin H, Kit B, Landrigan CP, Flores G. Family-centered rounds on pediatric wards: a PRIS network survey of US and Canadian hospitalists. Pediatrics. 2010;126(1):37–43. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollo V, Falzon P. Auto- and allo-confrontation as tools for reflective activities. Applied Ergonomics. 2004;35(6):531–540. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JS, Garg A. Participatory ergonomics in a red meat packing plant. Part II: case studies. American Industrial Hygeine Association Journal. 1997;58(7):498–508. doi: 10.1080/15428119791012595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muething SE, Kotagal UR, Schoettker PJ, Gonzalez Del Rey J, Dewitt TG. Family-centered bedside rounds: a new approach to patient care and teaching. Pediatrics. 2007;119(4):829–832. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid PR, Compton WD, Grossman JH, Fanjiang G. Building a Better Delivery System. A New Engineering/Health Care Partnership. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders MS, Mccormick EJ. Human Factors in Engineering and Design. 7th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sisterhen LL, Blaszak RT, Woods MB, Smith CE. Defining family-centered rounds. Teaching and Learning in Medicine. 2007;19(3):319–322. doi: 10.1080/10401330701366812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Carayon P. New technology, automation, and work organization: stress problems and improved technology implementation strategies. International Journal of Human Factors in Manufacturing. 1995;5(1):99–116. [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Carayon P. Balance theory of job design. In: Karwowski W, editor. International Encyclopedia of Ergonomics and Human Factors. London: Taylor & Francis; 2000. pp. 1181–1184. [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Carayon-Sainfort P. A balance theory of job design for stress reduction. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics. 1989;4(1):67–79. [Google Scholar]

- St-Vincent M, Chicoine D, Beaugrand S. Validation of a participatory ergonomic process in two plants in the electrical sector. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics. 1998;21(1):11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Stetler CB, Legro MW, Wallace CM, Bowman C, Guihan M, Hagedorn H, Kimmel B, Sharp ND, Smith JL. The role of formative evaluation in implementation research and the QUERI experience. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 2):S1–S8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00355.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramony A, Hametz PA, Balmer D. Family-centered rounds in theory and practice: an ethnographic case study. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14(2):200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomassen O, Brattebo G, Heltne JK, Softeland E, Espeland A. Checklists in the operating room: Help or hurdle? A qualitative study on health workers' experiences. Health Services Research. 2010;10:342–347. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomassen O, Espeland A, Softeland E, Lossius HM, Heltne JK, Brattebo G. Implementation of checklists in health care; learning from high-reliability organisations. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine. 2011;19:53–59. doi: 10.1186/1757-7241-19-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udo H, Kobayashi M, Udo A, Branlund B. Participatory ergonomic improvement in nursing home. Industrial Health. 2006;44(1):128–134. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.44.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Eerd D, Cole D, Irvin E, Mahood Q, Keown K, Theberge N, Village J, St Vincent M, Cullen K. Process and implementation of participatory ergonomic interventions: a systematic review. Ergonomics. 2010;53(10):1153–1166. doi: 10.1080/00140139.2010.513452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vats A, Vincent CA, Nagpal K, Davies RW, Darzi A, Moorthy K. Practical challenges of introducing WHO surgical checklist: UK pilot experience. British Medical Journal. 2010;340:133–135. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b5433. (jan13_2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vink P, Peeters M, Gründemann RWM, Smulders PGW, Kompier MaJ, Dul J. A participatory ergonomics approach to reduce mental and physical workload. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics. 1995;15(5):389–396. [Google Scholar]

- Waterson P. A critical review of the systems approach within patient safety research. Ergonomics. 2009;52(10):1185–1195. doi: 10.1080/00140130903042782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinger MB, Wiklund M, Gardner-Bonneau DJ, editors. Handbook of Human Factors in Medical Device Design. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JR. Fundamentals of ergonomics in theory and practice. Applied Ergonomics. 2000;31(6):557–567. doi: 10.1016/s0003-6870(00)00034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JR. Fundamentals of systems ergonomics/human factors. Applied Ergonomics. 2014;45(1):5–13. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JR, Haines H, Morris W. Participatory ergonomics. In: Wilson JR, Corlett EN, editors. Evaluation of Human Work. 3rd ed. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis; 2005. pp. 933–962. [Google Scholar]

- Winters BD, Gurses AP, Lehmann H, Sexton JB, Rampersad CJ, Pronovost PJ. Clinical review: checklists-translating evidence into practice. Critical Care. 2010;13(6) doi: 10.1186/cc7792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Alliance for Patient Safety. WHO guidelines for safe surgery. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Xie A, Carayon P. A systematic review of Human Factors and Ergonomics (HFE)-based healthcare system redesign for quality of care and patient safety. Ergonomics. 2014 doi: 10.1080/00140139.2014.959070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie A, Carayon P, Cartmill R, Li Y, Cox ED, Plotkin JA, Kelly MM. Multi-stakeholder collaboration in the redesign of family-centered rounds process. Applied Ergonomics. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie A, Carayon P, Kelly MM, Li Y, Cartmill R, Dubenske LL, Brown RL, Cox ED. Human Factors and Ergonomics Society's 56th Annual Meeting. Boston, MA: Managing different perspectives in the redesign of family-centered rounds in a pediatric hospitaled.^eds. Year. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Johnson TR, Patel VL, Paige DL, Kubose T. Using usability heuristics to evaluate patient safety of medical devices. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2003;36:23–30. doi: 10.1016/s1532-0464(03)00060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]