Abstract

Background

We previously developed and piloted a telephone-based intimacy enhancement (IE) intervention addressing sexual concerns of colorectal cancer patients and their partners in an uncontrolled study. The current study tested the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of the IE intervention in a randomized, controlled trial.

Methods

Twenty-three couples were randomized to either the four-session IE condition or to a wait list control condition and completed sexual and relationship outcomes measures. The IE intervention teaches skills for coping with sexual concerns and improving intimacy. Feasibility and acceptability were assessed through enrollment and post-treatment program evaluations, respectively. Effect sizes were calculated by comparing differences in average pre/post change scores across completers in the two groups (n = 18 couples).

Results

Recruitment and attrition data supported feasibility. Program evaluations for process (e.g., ease of participation) and content (e.g., relevance) demonstrated acceptability. Engaging in intimacy-building activities and communication were the skills rated as most commonly practiced and most helpful. For patients, positive effects of the IE intervention were found for female and male sexual function, medical impact on sexual function, and self-efficacy for enjoying intimacy (≥.58); no effects were found on sexual distress or intimacy and small negative effects for sexual communication, and two self-efficacy items. For partners, positive IE effects were found for all outcomes; the largest were for sexual distress (.69), male sexual function (1.76), communication (.97), and two self-efficacy items (≥.87).

Conclusions

The telephone-based IE intervention shows promise for couples facing colorectal cancer. Larger multi-site intervention studies are necessary to replicate findings.

Introduction

As survivorship lengthens for those with cancer, sexual quality of life is increasingly recognized as an area that warrants clinical attention [1]. For patients with colorectal cancer, sexual difficulties are common, distressing, and persistent, often lasting years after the end of treatment [2–5]. These sexual complaints include erectile dysfunction for men and decreased vaginal lubrication, vaginal atrophy, and pain during sexual intercourse for women [2,6–8]. Pelvic surgery, and in particular, surgery used to create an ostomy (i.e., external pouch for collection of stool) can directly affect sexual function through damaging nerves that enervate the genitals; ostomies also can impede intimacy through reducing sexual spontaneity and creating challenges such as leakage or visibility of the ostomy during sex [9–12]. Communication difficulties, sexual abstinence, and avoidance of sexual activity are also common intimacy effects due to colorectal cancer [13–15]. Partners of colorectal cancer patients also report significant sexual problems [16] and relationship interference [17], and there is some suggestion that they may be at an elevated risk for such problems compared with patients [16,17].

Given the challenges faced by patients with colorectal cancer and their partners, it is surprising that there are few psychosocial interventions addressing sexual function and intimacy focused on the unique needs of this population [18]. Previously, we developed an intervention addressing sexual and intimacy concerns of colorectal cancer patients and their spouses or partners (Intimacy Enhancement (IE); [19]) based on evidence-based sexuality interventions for cancer populations [20], theories of behavioral couples’ [21] and sex [22] therapy, and an approach we previously described as flexibility in coping with sexual concerns [23]. Rather than focusing on alleviating specific sexual dysfunctions, the telephone-based intervention centers on enhancing intimacy, which we have defined as an interpersonal process involving mutual sharing and understanding, feelings of closeness, warmth, and affection [19]. A small, uncontrolled pilot trial in 14 couples (nine completers) indicated that most participants rated the program highly on dimensions including ease of participation and helpfulness, perceived importance, and the telephone-based format. Most participants reported engaging frequently in the skills taught in the program and finding them helpful, with communication skills and sensual touching being rated particularly highly. Further, results suggested positive effects of the intervention on sexual distress and function, among other outcomes. However, with no control group against which to compare these changes, one cannot definitively conclude that they are the result of the IE intervention [19].

The purpose of the current study was to assess the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of the IE intervention in a small randomized, controlled trial in couples in which one partner was diagnosed with colorectal cancer. First, we expected that the IE protocol would be judged to be feasible as assessed through adequate recruitment, retention, and completion of sessions, and acceptable as assessed through participant evaluations of the intervention. Second, we hypothesized that, compared with patients and partners in a wait list control condition, patients and partners in the IE condition would show greater improvements in their reports of the quality of their sexual relationship (sexual distress, sexual communication, and intimacy). Finally, we hypothesized that patients and partners in the IE condition would report greater improvements in sexual function and self-efficacy (e.g., enjoying physical intimacy despite physical limitations) relative to couples in the wait list condition.

Methods

Participants

Patients were eligible if they (a) were 21 years of age or older (because participants younger than 21 years may have different types of sexual concerns), (b) were married or living with a partner for at least 1 year, (c) had undergone surgery or other treatment for colorectal cancer, and (d) were able to read and write English. To ensure that the intervention would be relevant and to allow for adequate improvement on outcomes, inclusion was limited to patients with sexual concerns (‘yes’ to ‘Have you noticed any changes in your intimate relationship or sex life since your cancer or its treatment?’ or ‘not at all’, ‘a little bit’, or ‘somewhat’ to ‘Over the past month, how satisfied have you been with your sex life?’). Other than speaking English and age >21 years, there were no specific inclusion/exclusion criteria for partners.

Procedures

All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Participants were recruited primarily through a prospective study examining the association between sexual outcomes and quality of life for colorectal cancer patients; once consented for the intervention study, however, they did not continue in the prospective study. Most patients (20/23; 87%) were initially contacted in clinic after identification through medical records screens or referrals from the Gastrointestinal (GI) Cancer Clinic oncology care providers; the remaining three patients responded to a study mailing after identification through the Johns Hopkins University cancer registry. Patients completing a baseline survey who met eligibility criteria on a paper and pencil screener were contacted through letter and follow-up phone call. Following completion of a detailed telephone oral consent process, participants were instructed to complete questionnaires independently and to return them in the mail; separate envelopes were provided. Baseline data from the prospective study were entered as pre-treatment data to reduce the burden of completing new surveys; three patients completed new baseline measures because >4 weeks passed to randomization. Randomization was stratified by patient gender and current ostomy use. Couples were reimbursed $25.00 for completion of each of the two study assessments.

Measures

Demographic and medical information was collected from patients and medical record data supplemented patient-reported medical information when possible.

Sexual distress

The Index of Sexual Satisfaction [24] consists of 25 items assessing sexual distress. Cronbach’s alpha=.95 and .91 for patients and partners, respectively.

Sexual communication

The 13-item Dyadic Sexual Communication Scale [25] was used to assess perceived quality of communication about sex in intimate relationships. Cronbach’s alpha = .88 and .90 for patients and partners, respectively.

Intimacy

The Miller Social Intimacy Scale [26] is a 17-item self-report questionnaire assessing the degree of emotional intimacy, closeness, and trust toward an individual’s significant partner. Cronbach’s alpha=.91 for both patients and partners.

Sexual function

Sexual function was assessed using the total sexual function scores from the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) [27] (19 items) and the International Index of Erectile Functioning (IIEF) [28] (15 items). Cronbach’s alpha for the Female Sexual Function Index = .99 and .97 for patients and partners, respectively. Cronbach’s alpha for the International Index of Erectile Functioning = .94 and .99 for patients and partners, respectively.

Medical impact on sexual function

The Medical Impact subscale of the Sexual Function Questionnaire [29] consists of five questions assessing the impact of a medical condition (in this case ‘colorectal cancer or its treatment’) on participants’ sexual function (i.e., desire, arousal, orgasm, and overall impact) and degree of adjustment to sexual difficulties. Cronbach’s alpha = .81 and .56 for patients and partners, respectively.

Self-efficacy

Participants were asked to rate their level of confidence in (a) communicating effectively about issues related to physical intimacy/sex, (b) dealing effectively with sexual difficulties, and (c) enjoying intimacy despite physical limitations. Responses were scored on a 10–100 scale with intervals of 10.

Feasibility and acceptability

Feasibility was measured through rates of study enrollment and participation, and acceptability was measured through three types of post-treatment ratings by patients and partners: (a) The overall ease of participation, helpfulness of the program, and relevance of the information provided (0 = not easy/helpful/relevant and 4 = extremely easy/helpful/relevant); (b) Agreement that the program met their expectations and was important to people with colorectal cancer and helpful to their intimacy, liking the telephone-based format, and being able to form good rapport with the therapist (1 = completely disagree and 10 = completely agree); and (c) Utilization of eight IE skills including the frequency (0=not at all and 4=more than once a day), ease of use, and helpfulness of each of the skills (0=not easy/helpful and 4 = extremely easy/helpful) over the past 2 weeks. Responses of >3 (at least ‘quite a bit easy/helpful’) were considered positive responses.

Intervention

Intimacy enhancement

The IE intervention has been described previously [19] and consists of four weekly 50-min telephone sessions teaching patients and their partners behavioral skills for coping with sexual challenges and improving both physical and emotional intimacy including techniques from both sex therapy and couple/marital therapy such as sensual touching exercises (i.e., sensate focus) [30], improving sexual communication, identifying and challenging overly negative or inflexible sexually related cognitions, and broadening the repertoire of both sexual and nonsexual intimacy-building activities. Each session includes a detailed agenda and focus on a specific skill (e.g., effective communication about intimacy), one or more skills practices in session (e.g., sharing exchange regarding the couple’s intimate relationship), and behavioral exercises explained and assigned for at-home practice (e.g., problem solving exchange to devise new intimacy activities).

Control group

A wait list (WL) control condition was chosen to ensure that all patients identified as having sexual concerns, and their partners would have the opportunity to participate in the IE intervention. After the time 2 surveys were collected from both members of the couple, the couple was offered the opportunity to participate in the intervention.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses examined recruitment rates, pre/post means on outcome measures for the two study conditions, and feasibility and acceptability measures. Baseline comparisons examined differences between study completers and noncompleters and between IE and WL groups (for patients and partners separately) using Chi-Sq for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous or semi-continuous variables; Pearson correlations among outcome variables were conducted. Because of the small sample size, for primary analyses, significance tests were not calculated for between-group comparisons of pre-post change and only complete data (i.e., data from participants available at both pre-treatment/post-treatment) were used. Using a procedure used in other small psychosocial intervention studies [31], pre-treatment to post-treatment change scores were calculated for each person. Between-group effect sizes were then calculated (group-wise difference in mean change scores/pooled change score standard deviation [SD]) [31]. Per convention, effect sizes were classified as large (≥.80), medium (.30–.60), and small (.20–.30). Program evaluation data from IE participants were examined using descriptive analyses. Analyses were conducted using SPSS Version 20 (IBM, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

Participants

Baseline demographic and medical data for study completers are presented in Table 1. Patients were mostly male (67%), Caucasian, highly educated, and working at least part time. All partners were opposite sex and were similar to patients in age (M = 53.1; SD = 11.0), race (88.9% White), and education (72.3% > high school). Over half of the patients in the sample (55.6%) had rectal cancer, and the same percentage had stage IV disease.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics of study completers

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 18) M (SD) | IE group (n = 10) M (SD) | WL group (n = 8) M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 52.6 (10.6) | 48.7 (11.0) | 57.4 (8.4) |

| Length of marriage/relationship (year) | 21.5 (10.6) | 17.4 (8.4) | 26.6 (11.4) |

| Time since diagnosis (months) | 23.3 (24.0) | 18.3 (18.7) | 29.6 (29.5) |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Gender (% female) | 6 (33.0) | 4 (40.0) | 2 (25.0) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 16 (88.9) | 9 (90.0) | 7 (87.5) |

| Education | |||

| High School/some college/associate’s degree | 9 (50.0) | 5 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 4 (22.2) | 2 (20.0) | 2 (25.0) |

| Graduate degree | 5 (27.7) | 3 (30.0) | 2 (25.0) |

| Employment status | |||

| Full/part time | 9 (50.0) | 6 (60.0) | 3 (37.5) |

| Retired | 6 (33.3) | 2 (20.0) | 4 (50.0) |

| Unemployed | 3 (16.7) | 2 (20.0) | 1 (12.5) |

| Rectal cancer (versus colon) | 10 (55.6) | 5 (50.0) | 5 (62.5) |

| Disease stage | |||

| Stage I or IIA | 3 (16.7) | 1 (10.0) | 2 (25.0) |

| Stage IIIB or IIIC | 5 (27.7) | 3 (30.0) | 2 (25.0) |

| Stage IV | 10 (55.6) | 6 (60.0) | 4 (50.0) |

| Pelvic surgery | 9 (50.0) | 4 (40.0) | 5 (62.5) |

| Past ostomy | 2 (11.1) | 1 (10.0) | 1 (12.5) |

| Current ostomy | 4 (22.2) | 2 (20.0) | 2 (25.0) |

| Currently on treatment | 9 (50.0) | 5 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) |

| Treatment | |||

| Chemotherapy | 15 (83.3) | 9 (90.0) | 6 (75.0) |

| Radiation | 9 (50.0) | 6 (60.0) | 3 (37.5) |

In analyses, race/ethnicity (White versus Black/other), highest degree (above versus below bachelor’s degree), and stage of disease (metastatic versus nonmetastatic) were dichotomized. Pelvic surgery data were obtained from medical records and were available for 13/18 patients (five WL; eight IE).

IE, intimacy enhancement; WL, wait list; SD, standard deviation.

Feasibility and acceptability

Study enrollment and participation

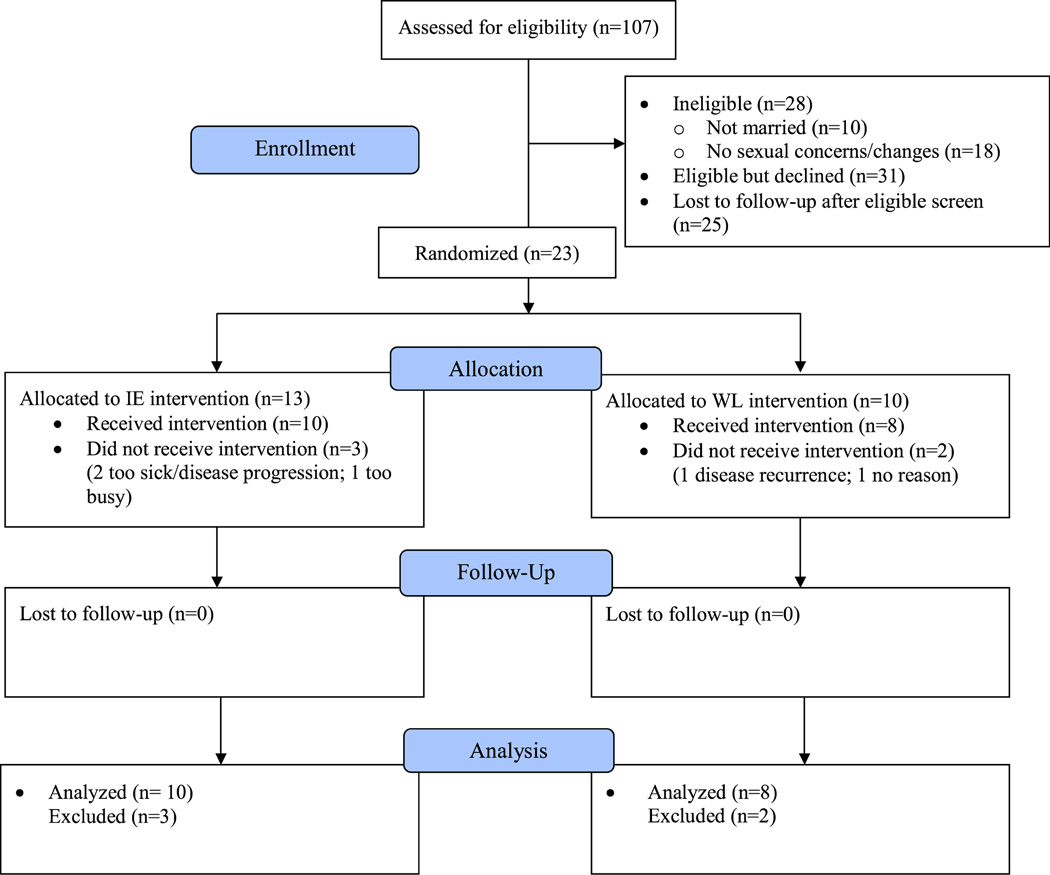

Figure 1 shows study enrollment. Of the 107 patients screened, 28 (26.2%) were excluded. Of the remaining 79 eligible patients, 31 (39.2%) did not agree to participate because of lack of patient or partner interest (10), lack of time (5), sexual problems not relevant (5), discomfort in discussing sex (4), no reason indicated (4), and feeling too ill (3). Twenty-five eligible couples indicated interest but were not responsive to multiple contact attempts. A total of 23 patients (29.1%) and partners consented for the study, 18 of whom completed the study (10 in IE group and eight in WL group). All 10 couples who started the IE sessions completed all four sessions and post-treatment surveys. Sessions generally occurred weekly; the duration of the intervention averaged 4.8 weeks (SD = 2.5).

Figure 1. Study consort diagram.

Program evaluation and skills utilization

Program evaluations and utilization of skills are presented in Table 2. Overall, participants rated the program favorably in terms of ease of participation, helpfulness, and relevance. Most participants liked the telephone-based nature of the program, and nearly all reported a high level of therapist rapport; other ratings were favorable. Most participants had used the skills within the past 2 weeks. Participating in an intimacy-building activity was rated by the largest proportion of participants as helpful and easy to use. Most other skills were rated by around half of participants as being helpful and easy to use.

Table 2.

Program evaluations and utilization of skills

| Program evaluations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall evaluations of program ease, helpfulness, and relevance | % rating as ≥ ‘quite a bit’ (3; range = 0–4) | ||

| Overall ease of participation in the program | 65 | ||

| Overall helpfulness of the program in improving intimacy | 90 | ||

| Information provided was relevant | 70 | ||

| Evaluations of program and rapport | % rating as ≥ 8/10 (range = 1–10) | ||

| Program met expectations | 89 | ||

| Believed this was an important program for people with colorectal cancer | 100 | ||

| Liked the telephone-based nature of the program | 90 | ||

| Was able to form good rapport with the therapist | 90 | ||

| Utilization of skills | |||

| Skill |

% using skill ≥ once in past 2 weeks |

% reporting the skill was ≥ quite a bit easy to use |

% reporting the skill was ≥ quite a bit helpful |

| Doing a focus on intimacy (sensate focus) exercise | 95 | 45 | 60 |

| Participating in an intimacy-building activity (not a focus on intimacy exercise) | 100 | 75 | 90 |

| Using ‘I’ statements when talking with your partner about sexuality or intimacy | 95 | 55 | 65 |

| Challenging negative thoughts | 95 | 45 | 75 |

| Trying a new sexual activity with your partner | 90 | 45 | 65 |

| Discussing your sexual wants and needs | 85 | 45 | 55 |

| Doing something to increase your sexual desire | 55 | 11 | 33 |

| Trying a strategy to solve a sexual problem | 40 | 21 | 37 |

Complete data from 20 participants were available for all items except for the following: the item ‘program met expectations’ (n = 19), items assessing the ease and helpfulness of the skill ‘trying to solve a sexual problem’ (n = 19 for both items), and items assessing the ease (n = 19) and helpfulness of ‘doing something to increase sexual desire’ (n = 18).

Preliminary efficacy

Baseline differences between patient study completers and noncompleters

Study patient completers (n = 18) were slightly older at diagnosis (p = .09) and less likely to hold a bachelor’s degree than noncompleters (n = 5; p = .06). Completers had lower intimacy (p = .03) and self-efficacy for communicating about sex (p = .03) compared with noncompleters.

Group baseline comparison and correlations among study variables

No significant baseline differences between IE and WL patients in demographic or medical variables or outcome measures were found (p values ≥ .11). No differences for partners approached significance (p values ≥ .25). When comparing IE and WL study completers, there were trends toward younger age (p = .07) and shorter relationship length (p = .08) for IE patients; female sexual function was slightly higher for IE patients at baseline compared with WL patients (p = .08). Baseline differences across patients and partners were also seen for several outcomes in the IE group (e.g., sexual function and two self-efficacy items) and WL group (e.g., sexual distress, sexual function, and self-efficacy). Correlations among study variables are presented in Table 3; all significant correlations went in expected directions.

Table 3.

Correlations among baseline variables for study completers (n = 36)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual distress and intimacy | ||||||||

| 1 Sexual distress* | ||||||||

| 2 Sexual communication | .59*** | |||||||

| 3 Intimacy | .72*** | .64*** | ||||||

| Sexual function | ||||||||

| 4 Female sexual function | .28 | .04 | .05 | |||||

| 5 Male sexual function | .18 | .04 | .11 | N/A | ||||

| 6 Impact on sexual function* | .54** | .12 | .13 | .40* | .44* | |||

| Self-efficacy | ||||||||

| 7 Enjoying intimacy | .79*** | .74*** | .65*** | .24 | .16 | 47** | ||

| 8 Communicating effectively | .58*** | .78*** | .66*** | .09 | .12 | .14 | .76*** | |

| 9 Dealing effectively | .68*** | .76*** | .64*** | .10 | .15 | .26 | .84*** | .90*** |

Sexual distress = Index of Sexual Satisfaction; sexual communication = Dyadic Sexual Communication Scale; intimacy = Miller Social Intimacy Scale; female sexual function = Female Sexual Function Index total score; male sexual function = International Index of Erectile Functioning total score; impact on sexual function = medical impact on sexual function subscale score.

Higher scores signify greater distress or worse impact.

p < .10.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Effect sizes for patients

Baseline and post-treatment means, SDs, and effect sizes are presented in Tables 4 and 5. Patient data showed a large effect size for an increase in female sexual function and medium to large effect sizes for reduction in medical impact on sexual function (.66) and self-efficacy for enjoying physical intimacy despite physical limitations (.66). Medium effect sizes were observed for improvement in male patients’ sexual function. There was no effect on sexual distress or intimacy. Small negative effects were observed for sexual communication and two self-efficacy items.

Table 4.

Means, standard deviations, and effect sizes of outcome variables for patients

| Colorectal cancer patients |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intimacy enhancement (n = 10) |

Wait list (n = 8) |

||||

| Measure | Pre M (SD) | Post M (SD) | Pre M (SD) | Post M (SD) | Effect size |

| Sexual distress and intimacy | |||||

| Sexual distress* | 30.7 (15.1) | 28.0 (17.6) | 47.2 (23.9) | 44.1 (24.6) | .05 |

| Sexual communication | 62.5 (11.3) | 59.6 (12.3) | 51.5 (15.6) | 52.3 (15.5) | .30 |

| Intimacy | 140.5 (21.1) | 137.1 (23.2) | 129.9 (15.0) | 127.3 (22.8) | .06 |

| Sexual function | |||||

| Female sexual function | 26.7 (6.2) | 30.0 (2.8) | 6.1 (5.8) | 6.8 (5.9) | .85 |

| Male sexual function | 37.3 (24.8) | 47.2 (17.3) | 41.8 (24.2) | 41.0 (24.1) | .58 |

| Impact on sexual function* | 2.8 (0.8) | 2.7 (1.0) | 2.9 (0.98) | 3.0 (1.1) | .66 |

| Self-efficacy | |||||

| Enjoying intimacy | 78.9 (13.6) | 80.0 (20.0) | 62.5 (33.7) | 48.8 (25.9) | .66 |

| Communicating effectively | 80.0 (17.3) | 86.7 (15.0) | 60.0 (33.4) | 66.3 (33.8) | .02 |

| Dealing effectively | 76.7 (15.0) | 78.9 (17.6) | 60.0 (33.4) | 63.8 (33.4) | .08 |

Measures are as presented in Table 3; effect sizes represent group-wise difference in mean change scores/pooled change score standard deviation (SD); complete data were available except for intimacy enhancement patients for intimacy (n = 8), female sexual function (n = 3), and the three self-efficacy items (n = 9). The clinical cut-off score indicating female sexual dysfunction on the Female Sexual Function Index is 26.55 [50]; whereas cut-off scores are not available for International Index of Erectile Functioning total scores, reference scores from a normal population are 60.8 (SD not available) [51].

Higher scores signify greater distress or worse impact.

Table 5.

Means, standard deviations, and effect sizes of outcome variables for partners

| Colorectal cancer partners |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intimacy enhancement (n = 10) |

Wait list (n = 8) |

||||

| Measure | Pre M (SD) | Post M (SD) | Pre M (SD) | Post M (SD) | Effect size |

| Sexual distress and intimacy | |||||

| Sexual distress* | 29.1 (12.4) | 22.7 (10.8) | 39.7 (19.8) | 39.7 (21.2) | .69 |

| Sexual communication | 54.8 (12.1) | 62.9 (10.0) | 58.4 (12.5) | 55.5 (16.1) | .97 |

| Intimacy | 141.4 (15.2) | 151.2 (12.2) | 136.8 (17.2) | 139.0 (27.8) | .51 |

| Sexual function | |||||

| Female sexual function | 18.4 (10.9) | 21.8 (8.7) | 18.1 (11.1) | 19.9 (9.5) | .18 |

| Male sexual function | 67.3 (3.5) | 72.3 (2.5) | 31.5 (36.1) | 31.0 (36.8) | 1.76 |

| Impact on sexual function* | 1.9 (0.4) | 1.7 (0.3) | 2.0 (0.8) | 2.0 (0.7) | .32 |

| Self-efficacy | |||||

| Enjoy intimacy | 78.0 (13.2) | 87.0 (11.6) | 73.8 (28.8) | 72.5 (26.1) | .57 |

| Communicate effectively | 63.0 (29.5) | 83.0 (14.2) | 75.0 (24.5) | 71.3 (25.3) | .88 |

| Deal effectively | 68.0 (23.5) | 87.0 (10.6) | 72.5 (29.6) | 70.0 (23.3) | .87 |

Measures are as presented in Table 3; effect sizes represent group-wise difference in mean change scores/pooled change score standard deviation (SD); complete data were available except for intimacy enhancement male sexual function (n = 3) and WL female sexual function (n = 5) and medical impact on sexual function (n = 7).

Higher scores signify greater distress or worse impact.

Effect sizes for partners

Data from partners showed large effect sizes for increases in sexual communication, male sexual function, and two self-efficacy items. Reductions in sexual distress showed a medium to large effect size (.69), and medium effect sizes were also found for improvements in medical impact on sexual function, intimacy, and one self-efficacy item. Female sexual function (.18) showed a minimal effect.

Discussion

Our findings support the feasibility and impact of a telephone-based couple intervention addressing sexual and intimacy concerns for colorectal cancer patients and their partners while also raising challenges for future research (e.g., recruitment, optimal screening methods). The IE intervention improved multiple domains for both patients and partners, which supports the breadth of the intervention as targeting both physical and emotional intimacy. Partners showed improvements on all sexual and relationship outcomes; patients improved in male and female sexual function, medical impact on sexual function, and self-efficacy for enjoying intimacy despite physical limitations. All participants rated the intervention as important and helpful, and participants in the IE intervention generally engaged frequently in the skills taught, suggesting that the intervention was acceptable. In the context of a larger study, collecting skills utilization data could facilitate an investigation of whether certain skills serve as mediators and could also be used to tailor further interventions. These ratings may also identify which intervention skills are most easily integrated into participants’ intimate relationships and most easily maintained over time, possibly yielding long-term benefits for couples.

Interestingly, the effects of the intervention were less consistent for patients, although the small sample size encourages caution in interpreting small effect sizes [32]. There are several possible explanations for the inconsistent findings. Baseline scores for sexual distress, intimacy, and sexual communication of IE patients in the current sample were comparable with those obtained at post-treatment in the pilot study [19], potentially representing a ceiling effect for patients in the IE group, and regression to the mean for some outcomes (i.e., sexual distress, intimacy, and communication). These baseline differences may also explain the small negative effects found for some patient outcomes. Screening for higher distress at baseline is important as participants entering cancer intervention studies with higher distress tend to be more likely to benefit than those with lower distress [33–35] and to ensure that the intervention does not inadvertently reduce quality or increase distress in high functioning couples. Interestingly, there is evidence that partners of cancer survivors report greater distress than patients [36,37]; in the case of sexual relationships, partners may feel reluctant to raise the issue for fear of burdening or pressuring the patient, and this may increase partner distress. Partners may also derive greater benefit from couple-based interventions compared with patients [38], perhaps because of the great value of opening communication with the patient about sensitive topics that might otherwise not be discussed.

Our recruitment rate was 29%, which is relatively similar to the typical rates found in other face-to-face couple-based or caregiver-assisted intervention studies (i.e., 30–50%) [31,34,39,40] and supports the feasibility of the study. Recruitment and attrition rates for couple-based telephone intervention studies in cancer populations [41,42] are generally comparable with those conducted face-to-face [43]. Attrition from the IE condition only occurred prior to the initial session; once a couple completed the initial session, they completed all four sessions and the post-treatment assessment, suggesting that once participants were engaged, they were highly motivated to complete the intervention. Sexuality-focused interventions face greater recruitment challenges given their specific focus and sensitivity of the topic [20,31,44,45]; couple-based interventions also require two persons to consent, rather than one, creating additional recruitment challenges. Because this intervention used a telephone-based format, the need to travel to the study site was not a barrier to participation. Rather, the most frequent reasons for not participating among eligible candidates were lack of interest or time, whereas those who chose to participate in the study initially reported lower intimacy and self-efficacy for communicating about issues related to physical intimacy and sex. Cancer survivors may be more amenable to sexual health interventions when they are at least a year past treatment completion [46]. Because half the current sample was currently undergoing treatment, focusing on survivors further out from treatment might generate greater interest and therefore yield higher recruitment rates. Future work assessing barriers to participation and preferences for interventions for study-eligible candidates who choose not to participate may inform the development of a range of interventions and enhance recruitment efforts.

The major limitation of this study is the small sample size, which likely compromised our ability to find significant effects for patients and is particularly relevant for the effects on sexual function by gender. As in other dyadic intervention studies [33,42], a larger trial would make it possible to examine whether certain subgroups (e.g., men or women, younger patients, those with poor communication) are more likely to benefit from the intervention than others. A larger trial would also allow sufficient power to examine dyadic effects of the intervention and whether patient or partner status moderates effects of the intervention. In order to accrue 64 couples, with a recruitment rate of 30%, approximately 213 patients have to be approached. This represents a large proportion of the colorectal cancer patients seen in a year in most cancer centers, suggesting that a multi-site trial is an appropriate next step for this research. Including a long-term follow-up is also needed, because it is possible that improvement in partners may precede and lead to improvement in patients.

Despite limitations, this study offers support for this telephone-based intimacy intervention, particularly for partners, and represents a step closer to providing empirically supported psychosocial treatments for sexual concerns among cancer survivors; such interventions are important given the scarcity of such psychosocial interventions available for couples facing colorectal cancer, in particular. It represents advancement from the prior study by including a control group and has the positive features of incorporating a comprehensive set of outcome and feasibility measures, a couple-based approach, and a novel telephone-based format. Telephone-based interventions reduce participant burden and show promise in addressing psychosocial concerns for cancer patients [42,47,48]. In support of this, the vast majority of participants liked the telephone format and several commented in qualitative post-treatment surveys (data not shown) that the ‘convenience of phone calls vs. office visits’ was a major advantage of the study format; one commented about feeling ‘more open to talk over the phone than face to face’, suggesting that this format may even be preferable to face-to-face by some participants when discussing the sensitive subject nature of this intervention. Participants also reported satisfaction with level of therapist rapport, which is important given recent findings that therapeutic alliance may predict improvement in psychosocial outcomes in telephone-based cognitive behavioral therapy interventions for cancer survivors [49]. Taken together, this research suggests telephone-based interventions may hold unique promise in addressing sensitive patient topics such as sexuality while reducing patient burden.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by American Cancer Society postdoctoral fellowship PF-09-154-01.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relationships that might bias this work or any conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Bober SL, Sanchez Varela V. Sexuality in adult cancer survivors: challenges and intervention. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3712–3719. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.7915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Traa MJ, De Vries J, Roukema JA, Den Oudsten BL. Sexual (dys)function and the quality of sexual life in patients with colorectal cancer a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:19–27. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chorost MI, Weber TK, Lee RJ, et al. Sexual dysfunction, informed consent and multi-modality therapy for rectal cancer. Am J Surg. 2000;179:271–274. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(00)00327-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmidt CE, Bestmann B, Kuchler T, et al. Ten-year historic cohort of quality of life and sexuality in patients with rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:483–492. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0822-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gervaz P, Bucher P, Konrad B, et al. A prospective longitudinal evaluation of quality of life after abdominoperineal resection. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97:14–19. doi: 10.1002/jso.20910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hendren SK, O’Connor BI, Liu M, et al. Prevalence of male and female sexual dysfunction is high following surgery for rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2005;242:212–223. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000171299.43954.ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nesbakken A, Nygaard K, Bull-Njaa T, et al. Bladder and sexual dysfunction after mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2000;87:206–210. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sterk P, Shekarriz B, Gunter S, et al. Voiding and sexual dysfunction after deep rectal resection and total mesorectal excision: prospective study on 52 patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2005;20:423–427. doi: 10.1007/s00384-004-0711-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Milbury K, Cohen L, Jenkins R, et al. The association between psychosocial and medical factors with long-term sexual dysfunction after treatment for colorectal cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2012;21:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1582-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaspatek MS, Hassan I, Cima RR, et al. Long-term quality of life and sexual and urinary function after abdominoperineal resection for distal rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:147–154. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31823d2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grant M, McMullen CK, Altschuler A, et al. Gender differences in quality of life among long-term colorectal cancer survivors with ostomies. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;38:587–596. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.587-596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neuman HB, Park J, Fuzesi S, Temple LK. Rectal cancer patients’ quality of life with a temporary stoma: shifting perspectives. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:1117–1124. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e3182686213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manderson L. Boundary breaches: the body, sex and sexuality after stoma surgery. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:405–415. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turnbull GB. Sexual counseling: the forgotten aspect of ostomy rehabilitation. J Sex Educ Ther. 2001;26:189–195. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tekkis PP, Cornish JA, Remzi FH, et al. Measuring sexual and urinary outcomes in women after rectal cancer excision. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:46–54. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e318197551e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Traa MJ, De Vries J, Roukema JA, Den Oudsten BL. The preoperative sexual functioning and quality of sexual life in colorectal cancer a study among patients and their partners. J Sex Med. 2012;9:3247–3254. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Northouse LL, Schafer JA, Tipton J, Metivier L. The concerns of patients and spouses after the diagnosis of colon cancer: a qualitative analysis. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 1999;26:8–17. doi: 10.1016/s1071-5754(99)90005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brotto LA, Yule M, Breckon E. Psychological interventions for the sexual sequelae of cancer: a review of the literature. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:346–360. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0132-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reese JB, Porter LS, Somers TJ, Keefe FJ. Pilot feasibility study of a telephone-based couples intervention for physical intimacy and sexual concerns in colorectal cancer. J Sex Marital Ther. 2012;38:402–417. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2011.606886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canada AL, Neese LE, Sui D, Schover LR. Pilot intervention to enhance sexual rehabilitation for couples after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104:2689–2700. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Epstein NB, Baucom DH. Enhanced cognitive behavioral therapy for couples: a contextual approach. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association (APA); 2002. In Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leiblum SR. Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reese JB, Keefe A, Somers TJ, Abernethy AP. Coping with sexual concerns after cancer: the use of flexible coping. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:785–800. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0819-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hudson WH, Harrison DF, Crosscup PC. A short-form scale to measure sexual discord in dyadic relationships. J Sex Res. 1981;17:157–174. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Catania JA. Help-seeking: an avenue for adult sexual development. San Francisco: University of California; 1986. In Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller RS, Lefcourt HM. The assessment of social intimacy. J Pers Assess. 1982;46:514–518. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4605_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, et al. The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49:822–830. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Syrjala KL, Schroeder TC, Abrams JR, et al. Sexual function measurement and outcomes in cancer survivors and matched controls. J Sex Res. 2000;37:213–225. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human Sexual Inadequacy. Boston: Little, Brown & Company; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baucom DH, Porter LS, Kirby JS, et al. A couple-based intervention for female breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2009;18:276–283. doi: 10.1002/pon.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kraemer HC, Mintz J, Noda A, et al. Caution regarding the use of pilot studies to guide power calculations for study proposals. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:484–489. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manne SL, Kissane DW, Nelson CJ, et al. Intimacy-enhancing psychological intervention for men diagnosed with prostate cancer and their partners: a pilot study. J Sex Med. 2011;8:1197–1209. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02163.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Given C, Given B, Rahbar M, et al. Effect of a cognitive behavioral intervention on reducing symptom severity during chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:507–516. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krischer MM, Xu P, Meade CD, Jacobsen PB. Self-administered stress management training in patients undergoing radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4657–4662. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matthews A. Role and gender differences in cancer-related distress: a comparison of survivor and caregiver self-reports. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2003;30:493–499. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.493-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kornblith AB, Herr HW, Ofman US, et al. Quality of life of patients with prostate cancer and their spouses. The value of a data base in clinical care. Cancer. 1994;73:2791–2802. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940601)73:11<2791::aid-cncr2820731123>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Northouse LL, Mood DW, Schafenacker A, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a family intervention for prostate cancer patients and their spouses. Cancer. 2007;110:2809–2818. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC, Given CW, Given B. A randomized, controlled trial of a patient/caregiver symptom control intervention: effects on depressive symptomatology of caregivers of cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2005;30:112–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manne SL, Ostroff JS, Winkel G, et al. Couple-focused group intervention for women with early stage breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:634–646. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mishel MH, Belyea M, Germino BB, et al. Helping patients with localized prostate carcinoma manage uncertainty and treatment side effects: nurse-delivered psychoeducational intervention over the telephone. Cancer. 2002;94:1854–1866. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Garst J, et al. Caregiver-assisted coping skills training for lung cancer: results of a randomized clinical trial. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2011;41:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Badr H, Krebs P. A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for couples coping with cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22:1688–1704. doi: 10.1002/pon.3200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manne S, Badr H. Intimacy and relationship processes in couples’ psychosocial adaptation to cancer. Cancer. 2008;112:2541–2555. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fredman SJ, Baucom DH, Gremore TM, et al. Quantifying the recruitment challenges with couple-based interventions for cancer: applications to early-stage breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2009;18:667–673. doi: 10.1002/pon.1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hill EK, Sandbo S, Abramsohn E, et al. Assessing gynecologic and breast cancer survivors’ sexual health care needs. Cancer. 2011;117:2643–2651. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Campbell LC, Keefe FJ, Scipio C, et al. Facilitating research participation and improving quality of life for African American prostate cancer survivors and their intimate partners—a pilot study of telephone-based coping skills training. Cancer. 2007;109:414–424. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DuHamel KN, Mosher CE, Winkel G, et al. Randomized clinical trial of telephone-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy to reduce post-traumatic stress disorder and distress symptoms after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3754–3761. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.8722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Applebaum AJ, DuHamel KN, Winkel G, et al. Therapeutic alliance in telephone-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy for hematopoietic stem cell transplant survivors. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80:811–816. doi: 10.1037/a0027956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wiegel M, Meston C, Rosen R. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. J Sex Marital Ther. 2005;31:1–20. doi: 10.1080/00926230590475206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dinsmore WW, Hodges M, Hargreaves C, et al. Sildenafil citrate (viagra) in erectile dysfunction: near normalization in men with broad-spectrum erectile dysfunction compared with age-matched healthy control subjects. Urology. 1999;53:800–805. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00586-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]