Summary

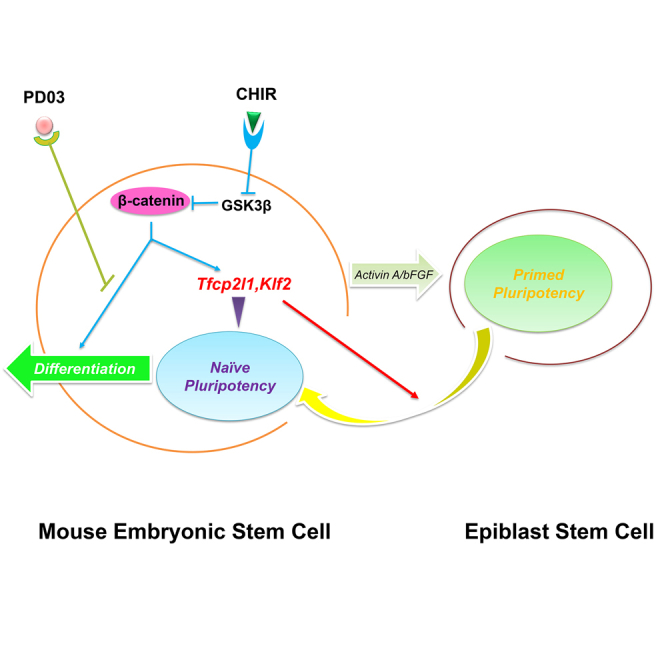

Activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling can induce both self-renewal and differentiation in naive pluripotent embryonic stem cells (ESCs). To gain insights into the mechanism by which Wnt/β-catenin regulates ESC fate, we screened and characterized its downstream targets. Here, we show that the self-renewal-promoting effect of Wnt/β-catenin signaling is mainly mediated by two of its downstream targets, Klf2 and Tfcp2l1. Forced expression of Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 can not only induce reprogramming of primed state pluripotency into naive state ESCs, but also is sufficient to maintain the naive pluripotent state of ESCs. Conversely, downregulation of Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 impairs ESC self-renewal mediated by Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Our study therefore establishes the pivotal role of Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 in mediating ESC self-renewal promoted by Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 are downstream targets of Wnt/β-catenin

-

•

Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 overexpression maintains mESC self-renewal

-

•

Downregulation of Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 impairs mESC self-renewal mediated by 2i

-

•

KLF2 and TFCP2L1 promote reprogramming of EpiSCs to naive ESCs

Wnt/β-catenin signaling can promote self-renewal as well as differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs). Ying and colleagues show that Klf2 and Tfcp2l1, two downstream targets of Wnt/β-catenin, play an essential role in mediating mESC self-renewal promoted by Wnt/β-catenin signaling.

Introduction

Since the first derivation of mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) (Evans and Kaufman, 1981; Martin, 1981), several culture conditions have been developed for the maintenance of undifferentiated mESCs in vitro, including the use of serum-containing medium supplemented with leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) (Smith et al., 1988; Williams et al., 1988) as well as serum-free N2B27 medium supplemented with LIF and bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) (Ying et al., 2003). LIF promotes mESC self-renewal by activating signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) (Niwa et al., 1998), while BMP4 can replace serum in supporting mESC self-renewal mediated by LIF/STAT3 (Ying et al., 2003). In 2008, we found that mESC self-renewal can be efficiently maintained by two small molecule inhibitors (2i), CHIR99021 and PD0325901 (CHIR and PD hereinafter) (Ying et al., 2008). CHIR and PD maintain self-renewal through inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) and mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK), respectively.

Previous reports have shown that inhibition of GSK3 by CHIR promotes mESC self-renewal through activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (Martello et al., 2012). In the absence of Wnt ligand or CHIR, T cell factor 3 (TCF3) occupies the promoter regions of many pluripotency genes (e.g., Nanog, Esrrb, etc.) and functions as a transcriptional repressor (Martello et al., 2012). Upon CHIR treatment, cytosolic β-catenin is stabilized and then translocates into the nucleus, where it binds to TCF3 and relieves its transcriptional repressing effect, leading to the upregulation of Wnt/β-catenin downstream target genes Nanog and Esrrb as well as other pluripotency genes suppressed by TCF3 such as Oct4 and Sox2 (Martello et al., 2012).

In mESCs, CHIR alone can only maintain short term (<1 week) self-renewal, after which mESCs will gradually undergo non-neural differentiation. LIF or PD, when supplemented with CHIR, is able to block such differentiation induced by CHIR and therefore maintains long-term self-renewal of mESCs (Ying et al., 2008). How CHIR collaborates with LIF or PD to maintain ESC self-renewal, however, remains poorly understood. We speculated that activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling by CHIR can upregulate the expression of both self-renewal-promoting genes and genes that induce differentiation, and addition of LIF or PD can repress the expression of differentiation genes induced by CHIR. In this study, we sought to dissect the effect of CHIR on promoting self-renewal from its effect on inducing differentiation. We identified Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 as the two key self-renewal-promoting targets of CHIR. When simultaneously overexpressed, these two genes can recapitulate the effect of 2i or LIF/CHIR on promoting mESC self-renewal.

Results

Genome-Scale Identification of Transcription Factors Differentially Regulated in mESCs by LIF and LIF/CHIR

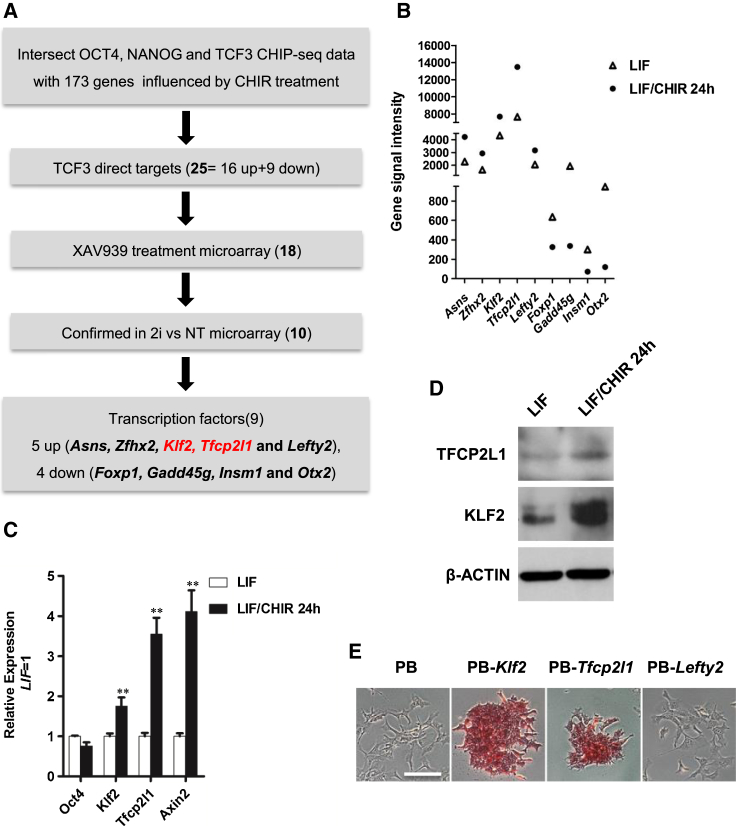

Inhibition of GSK3 by CHIR is likely to have pleiotropic transcriptional effects. To facilitate the identification of the self-renewal-promoting gene sets upregulated by CHIR in undifferentiated mESCs, we performed a gene expression microarray analysis in C57BL/6 mESCs treated with LIF or LIF/CHIR. LIF alone is not sufficient to maintain C57BL/6 mESC self-renewal under feeder-free condition and addition of CHIR is required (Ye et al., 2012). Because the major effect of CHIR is to promote C57BL/6 mESC self-renewal when LIF is present, we reasoned that by comparing gene expression profiles of C57BL/6 mESCs treated with LIF or LIF/CHIR, we should be able to narrow down CHIR targets that are associated with pluripotency maintenance. Candidate genes were first screened for changes of 1.5-fold or greater on expression level between LIF/CHIR and LIF conditions (GEO: GSE50393, p value < 0.01). Gene sets up- or downregulated by CHIR were then filtered according to published genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) data of OCT4, NANOG, and TCF3 (Martello et al., 2012). From such comparison, we singled out 25 candidates whose promoter regions are occupied by canonical Wnt transcription factor TCF3 as well as core pluripotency factors OCT4 and NANOG (Table S1). Among these 25 candidates, 16 are upregulated and 9 are downregulated (Figures 1A and 1B) after CHIR treatment.

Figure 1.

Genome-Scale Identification of Transcription Factors Involved in CHIR-Mediated ESC Self-Renewal

(A) Flow chart illustrating the approach used to identify candidate genes regulated by CHIR and associated with mESC self-renewal (see also Table S1).

(B) Scatter plots of DNA microarray data showing Asns, Zfhx2, Klf2, Tfcp2l1, Lefty2, Foxp1, Gadd45 g, Insm1, and Otx2 gene signal intensity from C57BL/6 mESCs cultured in serum/LIF/CHIR or serum/LIF for 24 hr.

(C) qRT-PCR analysis of Oct4, Klf2, Tfcp2l1, and Axin2 expression in C57BL/6 mESCs cultured in serum/LIF/CHIR or serum/LIF for 24 hr. Data represent mean ± SD of three biological replicates. ∗∗p < 0.01 versus LIF.

(D) Western blot analysis of 46C mESCs treated with LIF or LIF/CHIR for 24 hr.

(E) AP staining of C57BL/6 mESCs transfected with Klf2, Tfcp2l1, and Lefty2 and cultured in serum/LIF for two passages. Scale bar, 100 μm.

To further narrow down these candidates, we included microarray data from XAV939-treated cells (GEO: GSE31461) (Kim et al., 2013) as a filter. Authentic CHIR target genes should have an opposite expression pattern between CHIR and XAV939 treatments, as XAV939 is a potent inhibitor of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. At this point, 18 of the 25 candidate genes showed the expected expression pattern. To further validate this result, we checked the expression pattern of the 18 genes in the microarray data collected from 2i-treated cells (GEO: GSE46369) (Ye et al., 2013). In 2i condition, authentic CHIR candidate targets should have a similar expression profile as CHIR alone condition. Finally, ten genes were left for our further investigation, among which nine are transcription factors (Figure 1A). Transcription factors upregulated after CHIR treatment include Axns, Afhx2, Klf2, Tfcp2l1, and Lefty2. Transcription factors downregulated after CHIR treatment include Foxp1, Gadd45 g, Insm1, and Otx2 (Figures 1A and 1B). We focused on genes that are upregulated in LIF/CHIR condition compared with LIF alone and that are specifically expressed in pluripotent stem cells. Three genes, Klf2, Tfcp2l1, and Lefty2, comply with all these rules. Their expression levels in LIF/CHIR and LIF alone conditions were further validated by qRT-PCR analysis. Upon CHIR treatment, Klf2, Tfcp2l1, and Lefty2, as well as Axin2, a well-known target of the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling, were significantly upregulated while the expression of Oct4, a negative control for CHIR treatment, remained unchanged (Figure 1C). Western blot analysis also confirmed the upregulation of KLF2 and TFCP2L1 by CHIR at the protein level (Figure 1D). When overexpressed, Klf2 or Tfcp2l1, but not Lefty2, was able to maintain C57BL/6 mESC self-renewal under feeder-free condition in the presence of LIF and serum (Figure 1E), which is consistent with our previous findings (Ye et al., 2013). These results suggest that Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 are potentially the critical CHIR downstream targets responsible for mediating mESC self-renewal.

Forced Expression of Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 Recapitulates the Effect of 2i on Promoting mESC Self-Renewal

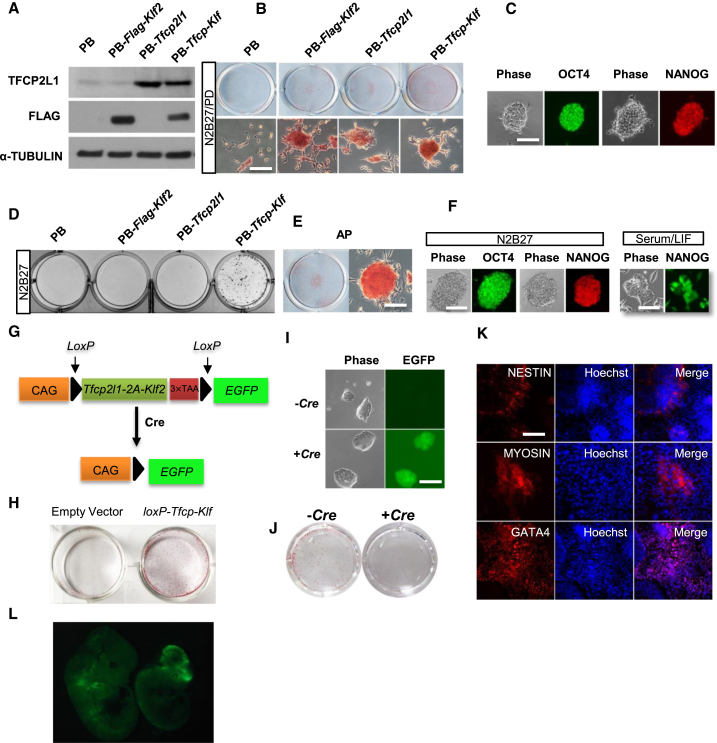

To further examine whether Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 can substitute the effect of 2i on promoting mESC self-renewal, we generated 46C mESCs expressing Klf2 (PB-Klf2 mESCs), Tfcp2l1 (PB-Tfcp2l1 mESCs), or both (PB-Tfcp-Klf mESCs) using the PiggyBac (PB) transposon-based vector. 46C mESCs were derived from 129 mouse strain and can be maintained under feeder-free condition in the presence of LIF and serum. The expression of KLF2 and TFCP2L1 proteins in the established cell lines was confirmed by western blot (Figure 2A). As expected, 46C mESCs transfected with PB empty vector differentiated or died within two passages in N2B27/PD condition. PB-Klf2, PB-Tfcp2l1, and PB-Tfcp-Klf mESCs, however, could be continuously propagated in N2B27/PD condition without overt differentiation (Figures 2B and 2C). Previous studies have shown that either Klf2 or Tfcp2l1 can partially recapitulate the effect of PD in promoting ESC self-renewal (Ye et al., 2013; Yeo et al., 2014). Indeed, PB-Tfcp-Klf mESCs could be continuously propagated in N2B27 only while PB-Klf2 and PB-Tfcp2l1 mESCs could not survive beyond five passages under this condition (Figures 2D–2F), suggesting that Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 acts synergistically to recapitulate the effect of 2i on promoting ESC self-renewal. The results were validated in another ESC line, the C57BL/6 ESCs (Figures S1A and S1B).

Figure 2.

Overexpression of Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 Can Replace 2i in Supporting mESC Self-Renewal in N2B27 Only Condition

(A) Western blot analysis of 46C mESCs overexpressing the indicated transgenes.

(B) AP staining of 46C mESCs overexpressing Klf2, Tfcp2l1, or both. ESCs were plated onto 6-well plates at a density of 2,000 cells/well and cultured in N2B27/PD condition for two passages. Top: representative images of AP staining in a 6-well plate. Bottom: representative images showing individual AP positive ESC colonies. Scale bar, 100 μm.

(C) Immunofluorescence staining of PB-Tfcp-Klf mESCs cultured in N2B27/PD for five passages. Scale bar, 100 μm.

(D) AP staining of colonies arisen from 46C mESC transfectants cultured in N2B27 only condition for two passages. Cells were plated at a density of 200 cells/well of a 6-well plate.

(E and F) AP and immunofluorescence staining of PB-Tfcp-Klf mESCs cultured in N2B27 only condition for ten passages. NANOG immunostaining of 46C mESCs cultured in serum/LIF was used as a control (see also Figure S1). Scale bar, 100 μm.

(G) Diagram showing Cre excisable construct used for Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 overexpression.

(H) AP staining of loxP-Tfcp-Klf mESCs cultured in N2B27 only condition for ten passages.

(I) Phase contrast and GFP images of loxP-Tfcp-Klf mESCs after transfection with or without Cre expression plasmid. ESCs were cultured in serum/LIF condition. Scale bar, 100 μm.

(J) AP staining of loxP-Tfcp-Klf mESCs (−Cre) and loxP-Tfcp-Klf mESCs in which the Tfcp-Klf transgene has been removed by Cre (+Cre). mESCs were cultured in N2B27 only condition for ten passages before AP staining.

(K) Immunofluorescence staining of differentiated cells derived from loxP-Tfcp-Klf mESCs in which the Tfcp-Klf transgene has been removed by Cre. Scale bar, 100 μm.

(L) Chimeric mouse embryos generated by injection of loxP-Tfcp2l1-2A-Klf2-loxP excised mESCs (GFP-positive) into C57BL/6 mouse blastocysts. Among 27 embryos analyzed between E11.5-E13.5, 13 contained GFP-positive cells.

Next, we tested whether the effect of Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 on ESC self-renewal is reversible. Based on the Cre/loxP recombination system, we constructed a double overexpression vector (Figure 2G) in which the coding sequences of Klf2 and Tfcp2l1, linked by 2A sequence, were flanked with loxP sites. The coding sequence of GFP was introduced in-frame following the loxP cassette to serve as a recombination reporter. In consistence with previous results, mESCs stably transfected with loxP-Tfcp2l1-2A-Klf2-STOP-loxP transgene (loxP-Tfcp-Klf mESCs hereinafter) could self-renew in N2B27 only condition (Figure 2H). After transient expression of Cre recombinase, the loxP-Tfcp2l1-2A-Klf2-loxP cassette was excised, as indicated by GFP expression (Figure 2I). In N2B27 only condition, GFP-positive cells differentiated (Figure 2J), indicating that the effect of Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 on ESC self-renewal is reversible. After excision of Tfcp2l1-2A-Klf2 transgene, these ESCs could be induced to differentiate into GATA4-positive primitive endoderm cells, MYOSIN-positive mesoderm cells, and NESTIN-positive ectoderm cells in vitro and contributed to chimera formation after blastocyst injection (Figures 2K and 2L), suggesting that Tfcp-Klf mESCs remain pluripotent.

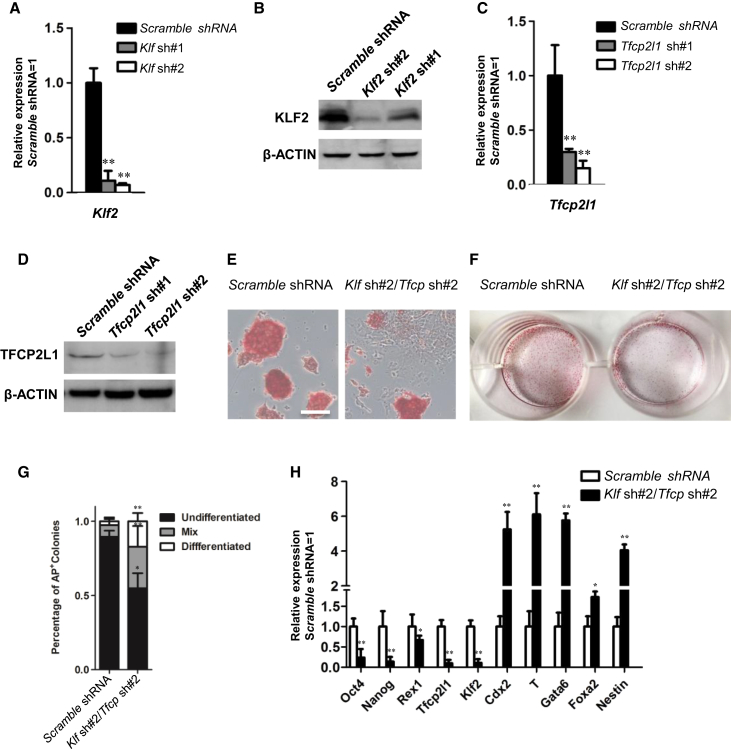

Downregulation of Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 Impairs ESC Self-Renewal

As shown above, forced expression of Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 is sufficient to maintain mESC self-renewal. Whether Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 are dispensable for mESC self-renewal in 2i condition, however, remains elusive. To address this question, we infected mESCs with lentiviruses encoding short-hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) specific to Klf2 and Tfcp2l1. Stable knock down of these two genes was confirmed by qRT-PCR and western blot analyses (Figures 3A–3D). As expected, single knock down of either gene has no obvious effect on mESC self-renewal in 2i condition (data not shown). We then selected the shRNAs with the highest knockdown efficiency (Klf2 shRNA #2 and Tfcp2l1 shRNA #2) to simultaneously knock down both Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 in mESCs. Under 2i culture condition, Klf2/Tfcp2l1 double knock down resulted in significant decrease of ESC colony forming efficiency, downregulation of pluripotency genes Oct4, Nanog, and Rex1, and upregulation of differentiation genes Cdx2, T, Gata4, Foxa2, and Nestin (Figures 3E–3H). These results suggest that Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 are necessary for mESC self-renewal mediated by 2i.

Figure 3.

Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 Knock Down Impairs 2i-Mediated mESC Self-Renewal

(A) qRT-PCR analysis of Klf2 expression in Klf2 shRNA knockdown 46C mESCs. Data represent mean ± SD of three biological replicates. ∗∗p < 0.01 versus scramble shRNA.

(B) Western blot analysis of KLF2 expression in Klf2 shRNA knockdown 46C mESCs.

(C) qRT-PCR analysis of Tfcp2l1 expression in Tfcp2l1 shRNA knockdown 46C mESCs. Data represent mean ± SD of three biological replicates. ∗∗p < 0.01 versus scramble shRNA.

(D) Western blot analysis of TFCP2L1 expression in Tfcp2l1 shRNA knockdown 46C mESCs.

(E and F) Klf sh#2/Tfcp2l1 sh#2 double-knockdown 46C mESCs were cultured in N2B27/2i for 10 days. Representative images showing individual AP positive ESC colonies (E) and AP staining in a 6-well plate (F). Scale bar, 100 μm.

(G) Quantification of AP-positive Klf sh#2/Tfcp2l1 sh#2 mESC colonies as shown in (F). Data represent mean ± SD of three biological replicates. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 versus scramble shRNA.

(H) qRT-PCR analysis of gene expression in scramble shRNA and Klf sh#2/Tfcp2l1 sh#2 knockdown mESCs cultured in N2B27/2i for two passages. Data represent mean ± SD of three biological replicates. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 versus scramble shRNA.

Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 Act Synergistically to Induce Naive Pluripotency

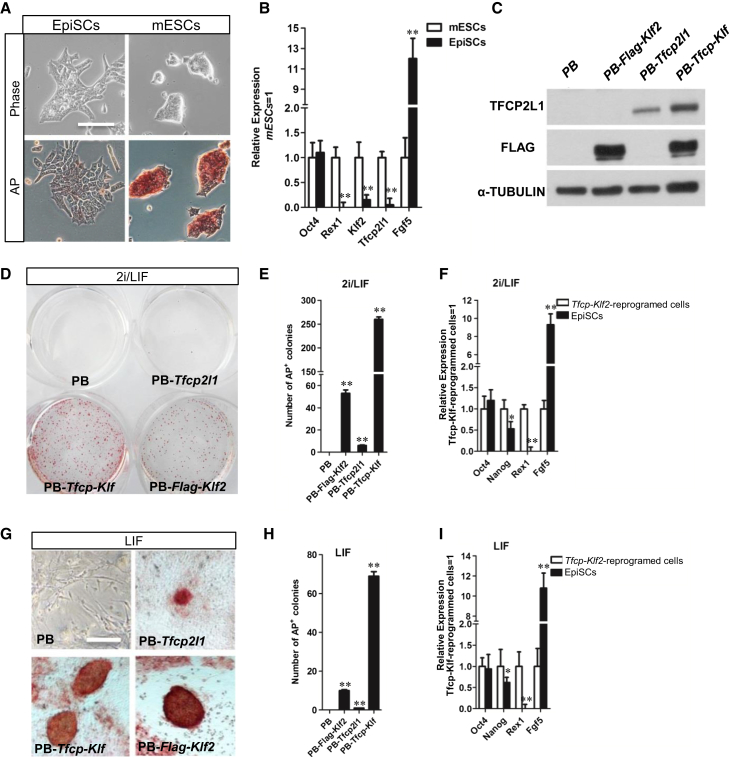

The primed state mouse epiblast stem cells (EpiSCs) can be converted back to naive state ESCs by forced expression of reprogramming factors (Hall et al., 2009; Ye et al., 2013). To achieve such reprogramming, EpiSCs need to be cultured under 2i condition. Given that Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 can mimic the effect of 2i, we next examined whether forced expression of Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 is sufficient to both induce and maintain naive pluripotency. To this end, we first differentiated mESCs into EpiSCs as described previously (Kim et al., 2013). The resulting EpiSCs stained negative for alkaline phosphatase (AP), expressed Oct4 and Fgf5, a post-implantation epiblast-specific marker, and exhibited a significant downregulation of naive pluripotency markers Rex1, Klf2, and Tfcp2l1 (Figures 4A and 4B), confirming their EpiSC identity. Next, we overexpressed Klf2, Tfcp2l1, or both in EpiSCs (Figure 4C). When cultured in serum/2i/LIF condition, EpiSCs overexpressing Klf2 or Tfcp2l1 gave rise to AP-positive ESC-like colonies within 8 days while EpiSCs transfected with empty PB vector died or differentiated within the same period of time (Figure 4D). As expected, EpiSCs overexpressing both Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 produced significantly more AP-positive colonies than those overexpressing Klf2 or Tfcp2l1 alone (Figure 4E). These EpiSC-converted ESC-like cells expressed high levels of naive pluripotency markers Nanog and Rex1, but low levels of primed state pluripotency maker Fgf5 (Figure 4F), indicating the successful conversion from primed state back to naive state pluripotency.

Figure 4.

Forced Expression of Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 Facilitates Reprogramming of EpiSCs into Naive State ESCs

(A) Phase contrast and AP staining images of EpiSCs converted from 46C mESCs after cultured in Activin A, bFGF, and XAV939 for ten passages (left). Right: 46C mESCs maintained in serum/LIF condition. Scale bar, 100 μm.

(B) qRT-PCR analysis of gene expression in 46C mESCs and EpiSCs converted from 46C mESCs. Data represent mean ± SD of three biological replicates. ∗∗p < 0.01 versus mESCs.

(C) Western blot analysis of 46C EpiSCs transfected with the indicated transgenes.

(D) Representative images showing AP staining of 46C EpiSCs transfected with the indicated transgenes and cultured in 2i/LIF for 15 days.

(E) Quantification of AP-positive colonies in (D). Data represent mean ± SD of three biological replicates. ∗∗p < 0.01 versus PB vector.

(F) qRT-PCR analysis of gene expression in 46C EpiSCs and Tfcp2l1/Klf2-reprogrammed cells cultured in 2i/LIF. Data represent mean ± SD of three biological replicates. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 versus Tfcp2l1/Klf2-reprogrammed cells.

(G) Representative images showing AP staining of 46C EpiSCs 10 days after transfection with the indicated transgenes. Cells were cultured in LIF only condition. Scale bar, 100 μm.

(H) Quantification of AP-positive colonies in (G). Data represent mean ± SD of three biological replicates. ∗∗p < 0.01 versus PB vector.

(I) qRT-PCR analysis of gene expression in 46C EpiSCs and Tfcp2l1/Klf2-reprogrammed cells cultured in LIF only condition. Data represent mean ± SD of three biological replicates. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01 versus Tfcp2l1/Klf2-reprogrammed cells.

Next, we tested whether Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 could induce naive state pluripotency in the absence of 2i. When cultured in serum/LIF condition, we observed that EpiSCs overexpressing both Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 could still be efficiently reprogrammed back to AP-positive ESC-like cells. In contrast, EpiSCs overexpressing Klf2 or Tfcp2l1 alone produced significantly less AP-positive colonies under the same condition (Figures 4G and 4H). The identity of the ESC-like cells converted from EpiSCs by overexpressing Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 in the absence of 2i was further confirmed by qRT-PCR (Figure 4I). Together, these results suggest that Kfl2 and Tfcp2l1 can act synergistically to reprogram EpiSCs to naive state ESCs in the absence of 2i.

Discussion

In this study, we have shown that Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 are the two key downstream targets of Wnt/β-catenin responsible for mediating mESC self-renewal. Overexpression of Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 can recapitulate the self-renewal-promoting effect of 2i in mESCs, whereas downregulation of Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 impairs ESC self-renewal. Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 can also facilitate the reprogramming of EpiSCs back to the naive pluripotent state. Our study therefore establishes KLF2 and TFCP2L1 as two key mediators of mESC self-renewal promoted by 2i.

Inhibition of GSK3 has dual effects on mESCs: promoting self-renewal and inducing non-neural differentiation (Ying et al., 2008). Previous reports have shown that CHIR exerts its function on promoting self-renewal through activation of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (Martello et al., 2012). Upon Wnt ligand or CHIR treatment, β-catenin, the central effector of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, induces the expression of several pluripotency genes, such as Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog, via suppression of TCF3 (Martello et al., 2012). In recent reports, Esrrb has been shown as a Wnt/β-catenin target in 129-derived mESCs (Martello et al., 2012). However, we did not observe such increase of Esrrb expression in our microarray data from C57BL/6-derived mESCs after CHIR treatment (GEO: GSE50393). Moreover, overexpression of Esrrb is not sufficient to support ESC self-renewal under serum-free condition (data not shown). On the contrary, Klf2 and Tfcp2l1, two downstream targets of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway (Martello et al., 2012), were upregulated upon CHIR treatment in our microarray data (Figure 1B) and play a pivotal role in mediating ESC self-renewal promoted by Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Figures 2D, 2E, and 3C). Both KLF2 and TFCP2L1 can upregulate Nanog expression to promote ESC self-renewal (Jiang et al., 2008; Ye et al., 2013) and Esrrb is a direct NANOG target gene that can substitute for NANOG function in mESCs (Festuccia et al., 2012). Therefore, it would be of great interest in future studies to determine the connection between Klf2/Tfcp2l1 and Esrrb in mediating ESC self-renewal.

Interestingly, KLF2 and TFCP2L1 are also involved in LIF/STAT3-mediated ESC self-renewal. KLF2, which is functionally redundant with KLF4, a known target of LIF/STAT3 signaling, can maintain mESCs in an undifferentiated state in the presence of serum (Hall et al., 2009). TFCP2L1, a key target of LIF/STAT3 signaling pathway, can also largely substitute the effect of LIF on ESC self-renewal (Martello et al., 2013; Ye et al., 2013). Notably, both KLF2 and TFCP2L1 can partially replace the function of PD on promoting ESC self-renewal (Ye et al., 2013; Yeo et al., 2014). However, when overexpressed alone, neither of them could maintain ESC self-renewal under serum-free condition in the absence of LIF and 2i (Figure 2D). It would be of great interest to explore how KLF2 and TFCP2L1 interact with each other in maintaining pluripotency.

Another important effect of KLF2 and TFCP2L1 we observed is to reprogram EpiSCs back to naive state ESCs (Figures 4D–4I). Both factors are highly expressed in mouse ESCs but barely detectable in EpiSCs (Hall et al., 2009; Ye et al., 2013). Previous studies have demonstrated that forced expression of each factor alone could reprogram EpiSCs back to ESCs when combined with 2i/LIF (Hall et al., 2009; Ye et al., 2013). In our study, we found that combined expression of Klf2 and Tfcp2l1 can convert EpiSCs back to ESCs in the absence of 2i (Figures 4G–4I), which is consistent with their function in mESC maintenance (Figure 2D). However, the underlying molecular mechanism of such a phenomenon needs to be further investigated. KLF2 and TFCP2L1 have been defined as two of the essential transcription factors for the induction of naive state pluripotency. Forced expression of Klf2 in combination with another pluripotency factor Nanog is sufficient to induce naive state pluripotency in human ESCs, which share many defining features with mouse EpiSCs (Takashima et al., 2014). Additionally, depletion of Tfcp2l1 in naive state human pluripotent stem cells collapses the naive pluripotent state (Takashima et al., 2014). Tfcp2l1 is highly expressed in the inner cell mass of human blastocysts but significantly downregulated during derivation of human ESCs (O’Leary et al., 2012), which suggests that TFCP2L1 might also play a role in establishing naive state pluripotency in human. Therefore, our study provides an expanded understanding of ESC self-renewal mechanism, a progress that might be critical in developing novel culture conditions for the derivation and maintenance of authentic ESCs from species other than rodents.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Culture

mESCs were routinely cultured on 0.1% gelatin-coated dishes in DMEM medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS (HyClone), 1% MEM non-essential amino acids (Invitrogen), 2 mM GlutaMAX (Invitrogen), 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Invitrogen), and 100 U/ml LIF. For serum-free culture, mESCs were maintained in N2B27 medium (Ying et al., 2008) supplemented with 3 μM CHIR and 1 μM PD (both synthesized in the Division of Signal Transduction Therapy, University of Dundee, UK).

Western Blot

Cells were lysed in ice-cold RIPA cell buffer (TEKNOVA) supplemented with Protease Inhibitors Cocktail (Thermo Scientific). Total protein was separated on a 4%–20% PAGE gel (Bio-Rad). The primary antibodies used were TFCP2L1 (N-20, Santa Cruz, 1:200), KLF2 (09-820, Millipore, 1:2,000), FLAG (M2, Sigma, 1:2,000), and α-tubulin (32-2500, Invitrogen, 1:2,000).

EpiSC Derivation and Reprogramming

For EpiSC derivation, 1 × 104 46C mESCs were plated into 0.1% gelatin-coated 35 mm dish and cultured in serum medium supplemented with Activin A (10 ng/ml, Peprotech), bFGF (10 ng/ml, Peprotech), and XAV939 (2 mM, Sigma). Cells were passaged every 3 days. For reprogramming, transfectants were seeded onto feeders-coated 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well. After 24 hr, the medium was changed to DMEM/10% FBS medium supplemented with or without LIF/2i and replaced every other day. The number of AP-positive colonies was counted under microscope.

Blastocyst Injection

Blastocysts were collected from E3.5 timed-pregnant C57BL/6 mice. mESCs (10–12) were injected into each blastocyst. mESC-injected blastocysts were transferred to E2.5 pseudo-pregnant CD1 mice. Animal experiments were performed according to the investigators’ protocols approved by the USC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Statistical Analysis

All data are reported as the mean ± SD. A Student’s t test was used to determine the significance of differences in comparisons. Values of p < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Author Contributions

D.Q. and S.Y. performed most of the experiments. B.R. and X.Z. carried out part of the experiments. Q.Z. and D.L. was involved in designing the experiments and analyzing the data. S.Y., D.Q., and Q.-L.Y. conceived and designed the study. D.Q., S.Y., X.Z., and Q.-L.Y. wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nancy Wu and Youzhen Yan for blastocyst injections. This work was supported by California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM) New Faculty Award II (RN2-00938), CIRM Scientific Excellence through Exploration and Development (SEED) (grant RS1-00327), Chen Yong Foundation of the Zhongmei Group, and in part by the Natural Science Foundation of China and Guangdong province (81370555, 81170452, S20120011190, and 2014B020228003), and Scientific Research Foundation of Anhui University (10117700027, 32030081, J10117700060, Y06050521, Y05201374, and Y06050519).

Published: August 27, 2015

Footnotes

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures, one figure, and two tables and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.07.014.

Accession Numbers

The accession number for the microarray dataset reported in this paper is Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO): GSE50393.

Supplemental Information

References

- Evans M.J., Kaufman M.H. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature. 1981;292:154–156. doi: 10.1038/292154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festuccia N., Osorno R., Halbritter F., Karwacki-Neisius V., Navarro P., Colby D., Wong F., Yates A., Tomlinson S.R., Chambers I. Esrrb is a direct Nanog target gene that can substitute for Nanog function in pluripotent cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:477–490. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J., Guo G., Wray J., Eyres I., Nichols J., Grotewold L., Morfopoulou S., Humphreys P., Mansfield W., Walker R. Oct4 and LIF/Stat3 additively induce Krüppel factors to sustain embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:597–609. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J., Chan Y.S., Loh Y.H., Cai J., Tong G.Q., Lim C.A., Robson P., Zhong S., Ng H.H. A core Klf circuitry regulates self-renewal of embryonic stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008;10:353–360. doi: 10.1038/ncb1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Wu J., Ye S., Tai C.I., Zhou X., Yan H., Li P., Pera M., Ying Q.L. Modulation of β-catenin function maintains mouse epiblast stem cell and human embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:2403. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martello G., Sugimoto T., Diamanti E., Joshi A., Hannah R., Ohtsuka S., Göttgens B., Niwa H., Smith A. Esrrb is a pivotal target of the Gsk3/Tcf3 axis regulating embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:491–504. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martello G., Bertone P., Smith A. Identification of the missing pluripotency mediator downstream of leukaemia inhibitory factor. EMBO J. 2013;32:2561–2574. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin G.R. Isolation of a pluripotent cell-line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem-cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1981;78:7634–7638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa H., Burdon T., Chambers I., Smith A. Self-renewal of pluripotent embryonic stem cells is mediated via activation of STAT3. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2048–2060. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.13.2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary T., Heindryckx B., Lierman S., van Bruggen D., Goeman J.J., Vandewoestyne M., Deforce D., de Sousa Lopes S.M., De Sutter P. Tracking the progression of the human inner cell mass during embryonic stem cell derivation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30:278–282. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A.G., Heath J.K., Donaldson D.D., Wong G.G., Moreau J., Stahl M., Rogers D. Inhibition of pluripotential embryonic stem cell differentiation by purified polypeptides. Nature. 1988;336:688–690. doi: 10.1038/336688a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashima Y., Guo G., Loos R., Nichols J., Ficz G., Krueger F., Oxley D., Santos F., Clarke J., Mansfield W. Resetting transcription factor control circuitry toward ground-state pluripotency in human. Cell. 2014;158:1254–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams R.L., Hilton D.J., Pease S., Willson T.A., Stewart C.L., Gearing D.P., Wagner E.F., Metcalf D., Nicola N.A., Gough N.M. Myeloid leukaemia inhibitory factor maintains the developmental potential of embryonic stem cells. Nature. 1988;336:684–687. doi: 10.1038/336684a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye S., Tan L., Yang R., Fang B., Qu S., Schulze E.N., Song H., Ying Q., Li P. Pleiotropy of glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibition by CHIR99021 promotes self-renewal of embryonic stem cells from refractory mouse strains. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e35892. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye S., Li P., Tong C., Ying Q.L. Embryonic stem cell self-renewal pathways converge on the transcription factor Tfcp2l1. EMBO J. 2013;32:2548–2560. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo J.C., Jiang J., Tan Z.Y., Yim G.R., Ng J.H., Göke J., Kraus P., Liang H., Gonzales K.A.U., Chong H.C. Klf2 is an essential factor that sustains ground state pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:864–872. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying Q.L., Nichols J., Chambers I., Smith A. BMP induction of Id proteins suppresses differentiation and sustains embryonic stem cell self-renewal in collaboration with STAT3. Cell. 2003;115:281–292. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00847-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying Q.L., Wray J., Nichols J., Batlle-Morera L., Doble B., Woodgett J., Cohen P., Smith A. The ground state of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nature. 2008;453:519–523. doi: 10.1038/nature06968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.