Abstract

Background

Adipose tissues play important role in the pathophysiology of obesity-related diseases including type 2 diabetes (T2D). To describe gene expression patterns and functional pathways in obesity-related T2D, we performed global transcript profiling of omental adipose tissue (OAT) in morbidly obese individuals with or without T2D.

Methods

Twenty morbidly obese (mean BMI: about 54 kg/m2) subjects were studied, including 14 morbidly obese individuals with T2D (cases) and 6 morbidly obese individuals without T2D (reference group). Gene expression profiling was performed using the Affymetrix U133 Plus 2.0 human genome expression array. Analysis of covariance was performed to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Bioinformatics tools including PANTHER and Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) were applied to the DEGs to determine biological functions, networks and canonical pathways that were overrepresented in these individuals.

Results

At an absolute fold-change threshold of 2 and false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05, 68 DEGs were identified in cases compared to the reference group. Myosin X (MYO10) and transforming growth factor beta regulator 1 (TBRG1) were upregulated. MYO10 encodes for an actin-based motor protein that has been associated with T2D. Telomere extension by telomerase (HNRNPA1, TNKS2), D-myo-inositol (1, 4, 5)-trisphosphate biosynthesis (PIP5K1A, PIP4K2A), and regulation of actin-based motility by Rho (ARPC3) were the most significant canonical pathways and overlay with T2D signaling pathway. Upstream regulator analysis predicted 5 miRNAs (miR-320b, miR-381-3p, miR-3679-3p, miR-494-3p, and miR-141-3p,) as regulators of the expression changes identified.

Conclusion

This study identified a number of transcripts and miRNAs in OAT as candidate novel players in the pathophysiology of T2D in African Americans.

Keywords: Obesity, Global gene expression, Type 2 diabetes, African Americans

Introduction

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes (T2D) has risen concomitantly with that of obesity in virtually every country in the world [1, 2]. The International Obesity Task Force estimates that up to 1.7 billion people of the world’s population are at a heightened risk of weight-related, non-communicable diseases such as T2D. The International Diabetes Federation predicts that the number of people with diabetes will rise from 194 million today to more than 333 million by 2025. In the US, about 35.7% of adults are obese and more than 11% of adults aged 20 years and older have diabetes, a prevalence expected to increase to approximately 21% by 2050 [3–5]. Ethnic minority groups, including African Americans, have a higher prevalence of obesity and are therefore at higher risk of developing obesity-related co-morbidities than other ethnic groups [6–8]. The molecular mechanisms that underline the development of T2D in obesity are still not well understood [9]. A number of studies have investigated these mechanisms in animal models or in tissues and organs that are directly involved in insulin metabolism such as pancreas, liver, and smooth muscle [9–16].

White adipose tissue [17] is now well recognized as an important endocrine organ that produces large number of bio-molecules involved in glucose and lipids metabolism and inflammation [18]. These observations have led to intense investigation of the role of WAT in the pathophysiology of T2D. Gene expression arrays have been used to investigate the expression patterns of visceral adipose tissue (VAT) from morbidly obese and lean individuals [19, 20]. Also, the expression profiles of VAT and subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) in non -diabetic obese men have been investigated [21]. Other studies have conducted gene expression profiling in obese individuals with insulin resistance, a physiological state often occurring before the development of T2D [22]. A number of pathways and candidate genes have been reported to be associated with obesity including those related to glucose and lipids metabolism, membrane transport, cell cycle promotion and immunity – complements C2, C3, C4 [9]. While these studies have contributed to our knowledge of the pathophysiology of obesity or obesity-related insulin resistance, identifying putative pathways that are more directly involved in obesity-related T2D remains crucially important. For example, it is well documented that insulin secretion and action are impaired in T2D but the exact mechanisms underlying this observation are not well understood especially in insulin-targeted tissue such as adipose tissues (ATs) [23–25]. In vitro experiments show that insulin receptor substract-1 (IRS1), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-kinase) and small Rho family such as TC10 and cell division cycle 42 (cdc42) pathways are involved in insulin-induced glucose transport. However, these findings were observed in non-diseased state. In the present study, we utilize a global expression profiling approach to provide insight into gene expression patterns and pathways that may be affected in persons with T2D in the context of obesity.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

A total of 20 morbidly obese African Americans (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2) were included in this study. Clinical and demographic data as well as OAT samples were obtained from Zen-Bio, Inc. (Research Triangle, NC). The participants in this study were undergoing elective surgical procedures and agreed to donate their de-identified discarded tissues for research. All participants underwent pre-operative clinical assessments by their physicians and diabetes status was determined at the time by the treating physicians using standard procedures. The characteristics of the 20 obese subjects (14 morbidly obese diabetics – “cases” and 6 morbidly obese non-diabetics – “reference”) are summarized in Table 1. One sample was determined as a microarray hybridization outlier after quality control (QC) and was excluded from subsequent analyses.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants

| Parameters | Obese non diabetic (control: n=6) | Obese diabetic (cases: n=14) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGE (years) | 41.0±4.6 (36–47) | 41.5±9.1 (27–61) | 0.87 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 53.9±7.1 (45.6–65) | 54.9±7.8 (44.1–73.5) | 0.79 |

| WAIST (inches) | N/A | 55.8±3.3 (51–60) | - |

| FBG (mg/dl) | N/A | 128.1±25.5 (81–172) | - |

Values presented are mean ±Standard deviation; values in parenthesis are ranges. Mean between groups were compared by Student’s t-test. FBG: fasting blood glucose

RNA extraction and quantification

Total RNA was extracted from OAT using EZ1 RNA universal kit and the EZ1 workstation (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA). Briefly 100 mg of frozen OAT was disrupted and homogenized in 750 μl of QIAzol lysis reagent using a tissuelyzer (Qiagen Inc, Valencia, CA). Then 150 μl of chloroform was added to the homogenate and centrifuged. After centrifugation, the sample separates into 3 phases. The upper aqueous phase containing the RNA was transferred to a new tube and processed with EZ1 RNA universal tissue kit on the EZ1 workstation following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quantity and quality were assessed using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) and Nanodrop (Thermo Fisher, Wilmington, DE).

RNA amplification, labeling, and microarray hybridization

Per RNA labeling, 500 ηg of total RNA was used in conjunction with the Illumina® TotalPrep RNA Amplification Protocol (Ambion/Applied Biosystems, Cat#AMIL1791). The hybridization cocktail containing the fragmented and labeled cRNAs was hybridized to the Affymetrix Human Genome U133 2.0 Gene Chip. The chips were washed and stained by the Affymetrix Fluidics Station using the standard format and protocols as described by Affymetrix. The probe arrays were stained with streptavidin phycoerythrin solution (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) and enhanced by using an antibody solution containing 0.5 mg/mL of biotinylated anti-streptavidin (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). An Affymetrix Gene Chip Scanner 3000 was used to scan the probe arrays. Probe cell intensity data (Affymetrix CEL files) were generated using Affymetrix GeneChip Command Console (AGCC) software. The microarray platform and data have been submitted to the Gene Expression Omnibus public database at NCBI following MIAME guidelines (GEO accession: GSE71416) [26].

Validation of gene expression results from Microarray by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)

To validate the microarray results, genes were selected using the following criteria 1) upregulated gene (TBRG1); 2) down regulated genes (MAGOH, PDIA3, ARPC3) 3) genes previously associated with diabetes in humans and animal models or associated with type 2 diabetes or insulin secretion in genome wide scan studies (TBRG1, COL4A2, PDIA3); 4) genes associated with significant canonical pathways among DEGs (HNRNPA1, BAX, PIP5K1A, P1P4K2A) and 5) transcripts with expression fold change (FC) lower than 2 were also included in this step (BLCAP, COL4A2).

RNA samples were reverse transcribed using iScript™ cDNA synthesis kit with random primers for the qRT-PCR following the manufacturer’s instructions (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA). The qRT-PCR assay was then carried out on MyIQ system (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA) using previously synthesized cDNA and TaqMan gene expression assays which include 2 unlabeled PCR primers and 1 FAM® dye-labeled TaqMan® MGB probe (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies Corporation, Carlsbad, CA). A sample volume of 25 μl was used for all assays and contained 12.5 μl of 2X TaqMan universal PCR mix, 1.25 μl of 20X Taqman gene expression assay mix and 11.25 μl of cDNA diluted in RNase-free water. All runs included duplicates of the samples and triplicates of negative control without the target DNA. The thermal cycling conditions were: 25°C for 5 min, 42°C for 30 min and 85°C for 5 min and 4°C forever.

Data Analysis

To identify genes or biological pathways that may be associated with T2D in obesity, we determined the gene expression profiles of OAT from morbidly obese diabetics (cases) and morbidly obese non-diabetics (reference). The generated global gene expression data were assessed by two different methods: Differential expression analysis and functional classification of differentially expressed genes (DEGs).

Affymetrix microarray CEL files with probe cell information were further processed in Partek Genomics Suite 6.0 (St Louis, MO) and were summarized into probe-set level data with robust multi-array average (RMA) algorithm [27]. QC of the data and analysis of covariance to identify DEGs among cases and reference were performed subsequently. The threshold for significance in expression change was set at FC ≤ −2 for downregulated genes, FC ≥ 2 for upregulated and false discovery rate (FDR) using Benjamini-Hochberg procedure < 0.05. Classification of DEGs into biological processes was done using Protein ANalysis Through Evolutionary Relationship (PANTHER, www.pantherdb.org) [28]. Pathways and interaction networks analyses were performed using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA®) by uploading the 68 DEG’s Affymetrix probe identification. The significance of canonical pathways and interaction networks was tested using Fisher’s exact test.

To understand the gene expression changes observed in this dataset, we used IPA® upstream regulator analytic tool which is based upon prior knowledge of expected effects between transcriptional regulators and their targeted genes stored in the Ingenuity®Knowledge Base. This tool not only allows identifying potential regulators, which may or may not be differentially expressed, that are involved in the expression change seen but predicts their activation/inhibition. Two statistical measures determined the significance of the upstream regulators identified, the overlap p-value calculated using Fisher’s exact test (significance cut-off is p<0.01) and activation Z- score which is used to infer the activation state of the regulators [29].

The qRT-PCR data was analyzed using Relative Expression Software Tool (REST 2009), a stand-alone software developed by Pfaffl and Qiagen (http://www.REST.de.com) and uses the ΔΔCt method. The expression values were normalized to a reference gene, GAPDH (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies Corporation, Carlsbad, CA). Two criteria were used to confirm the microarray results : a quantitative measure namely Spearman’s coefficient correlation (Rho) between qRT-PCR and micro-array results and a qualitative measure which is the consistency in the direction of the change in expression between RT-PCR and microarray. The coefficient of correlation and statistical significance were determined using IBM SPSS Statistics v.19; the input data for this analysis was the calculated FCs from the array and the average relative FCs from the RT-PCR experiment.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

The characteristics of the 20 AA individuals that provided omental adipose tissue (OAT) samples are summarized in Table 1. Six of the 20 individuals were in the reference group (i.e. BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 and no diabetes); the remaining 14 individuals were cases (i.e. BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 and diabetes). Fifteen of the 20 subjects were women, and mean BMI and age for the entire sample were 54.6 kg/m2 and 41.1 years, respectively. Cases and individuals in the reference group were not statistical different with respect to BMI and age. The mean plasma fasting glucose for cases was 128.1 mg/dl.

Global gene expression profiling in OAT

Using an absolute expression FC of 2 (FC≤− 2, FC ≥ 2) and FDR < 0.05, we identified 68 differentially expressed transcripts in cases relative to the reference group (Supplemental Table 1). The most highly DEGs between the two groups are presented in Table 2. About 3% of the DEGs including myosin X (MYO10, FC=2.3) and transforming growth factor beta regulator 1 (TBRG1, FC=2.0) were upregulated in the cases while the remaining including metastasis associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1, (MALAT1, FC=−9.8), mago-nashi homolog, proliferation-associated (MAGOH, FC=−6.8), actin related protein 2/3 complex, subunit 3 (ARPC3, FC=-5.0) and PDIA3, FC=−5.8) were downregulated.

Table 2.

List of the most highly differentiated genes in omental adipose tissue of morbidly obese and diabetic African Americans

| Gene Symbol | Gene name | FC | P-value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated Transcripts | ||||

| MYO10 | Myosin X | 2.3 | 1.1×10−4 | 3.8×10−2 |

| TBRG1 | Transforming growth factor beta regulator 1 | 2.0 | 1.8×10−4 | 4.9×10−2 |

| Downregulated Transcripts | ||||

| MALAT1 | Metastasis associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (non-protein coding) | −9.8 | 1.4×10−7 | 4.9×10−4 |

| MAGOH | Mago-Nashi homolog, proliferation-associated (Drosophila) | −6.8 | 3.6×10−5 | 1.9×10−2 |

| NR1D2 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group D, member 2 | −6.5 | 1.1×10−5 | 9.3×10−3 |

| HIRA | Histone cell cycle regulator | −6.5 | 3.0×10−8 | 1.8×10−4 |

| PDIA3 | Protein disulfide isomerase family A, member 3 | −5.8 | 1.5×10−7 | 4.9×10−4 |

| ARPC3 | Actin related protein 2/3 complex, subunit 3, 21kDa | −5.0 | 1.0×10−8 | 1.6×10−4 |

| HNRNPA1 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 | −4.5 | 1.1×10−4 | 3.8×10−2 |

| HIVEP2 | Human immunodeficiency virus type I enhancer binding protein 2 | −4.4 | 3.7×10−5 | 1.9×10−2 |

| NBPF10 | Neuroblastoma breakpoint family member 21-like | −4.4 | 2.4×10−6 | 3.4×10−3 |

| NUCKS1 | Nuclear casein kinase and cyclin-dependent kinase substrate 1 | −4.1 | 5.7×10−5 | 2.6×10−2 |

FC, fold change; FDR, false discovery rate.

Functional classification of DEGs in morbidly obese diabetic

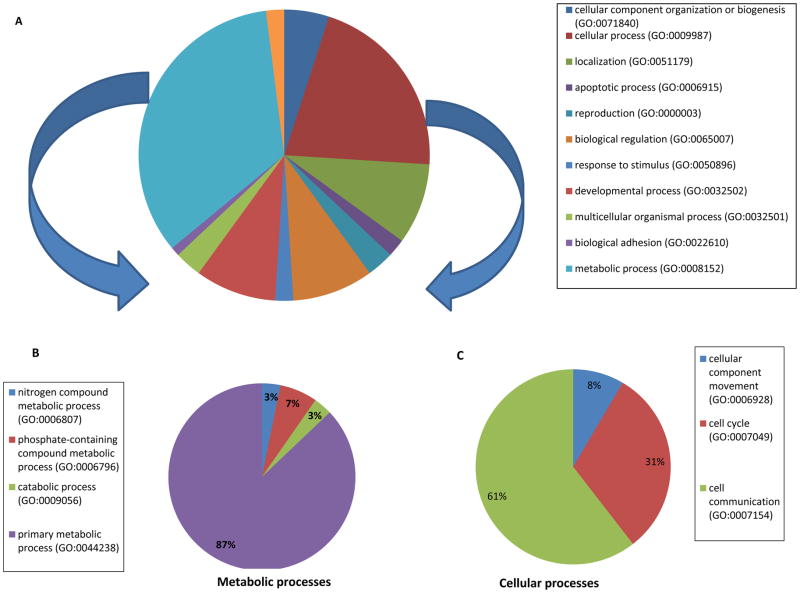

To determine the biological functions represented by the DEGs in OAT of these individuals, we evaluated the gene set of 68 DEGs using PANTHER and identified 2 major biological functions mainly metabolic processes and cellular processes (Figure 1A). In fact, metabolic and cellular processes represent about 55% of all biological processes (Supplemental Table 2). A detailed breakdown of these two major biological functions is depicted in Figures 1B and 1C. Interestingly, 27 of the 34 DEGs classified in the metabolic process were associated with lipids, carbohydrates, proteins, and nucleobase-containing compound metabolisms. Notably, nucleotide metabolism is the most represented function among the primary metabolic processes (19/27 DEGs i.e. about 70%, Supplemental Table 3). Few of the DEGs were associated with more than one biological functions e.g. ING3 which plays a role both in carbohydrate and nucleotide metabolism. Other specialized biological functions were also present including immune system, localization (transport and RNA localization), and response to stimulus (Figure 1A, Supplemental Table 2)

Figure 1. Classification of DEGs among morbidly obese diabetes into biological functions.

A. Pie chart represents all biological functions represented by the 68 DEGs; metabolic and cellular processes denote the 2 biological classes the most represented.

B. Pie chart represents a breakdown of the metabolic processes shown in Figure 1A

C. Pie chart represents a breakdown of the cellular processes shown in Figure 1A

IPA canonical pathways and interaction networks associated with DEGs in OAT of morbidly obese diabetic

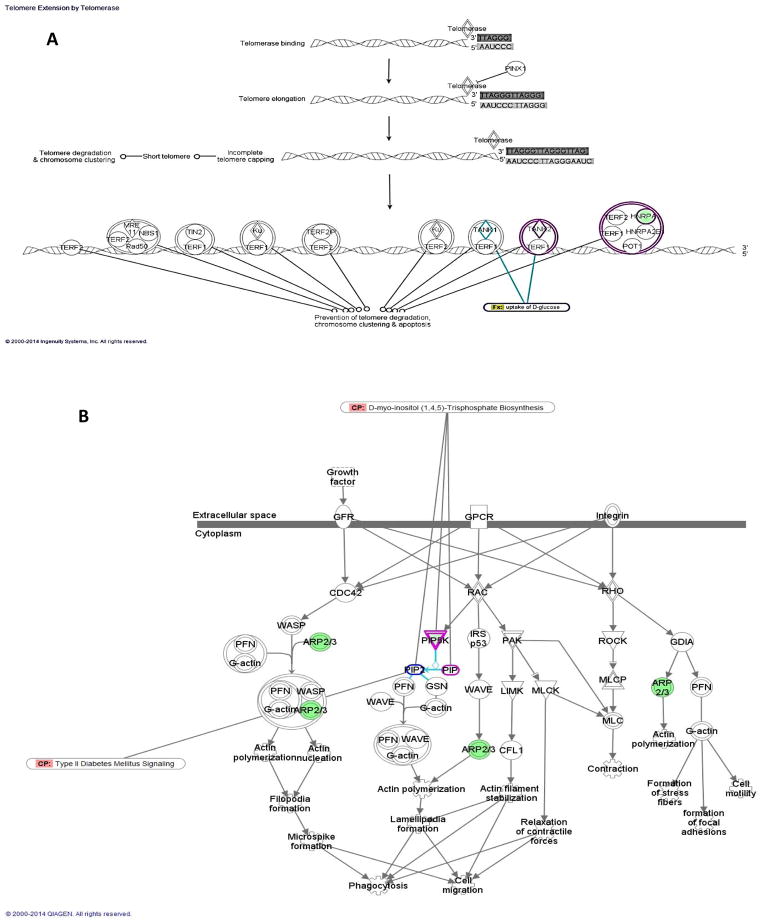

In addition to the biological functions, pathway analysis was carried out using the core analysis feature of IPA to determine the most enriched pathways among the DEGs in obese diabetics. The most enriched canonical pathways were telomere extension by telomerase implicating two DEGs that are involved in nucleotide metabolism specifically in DNA replication and RNA processing (HNRNPA1, TNKS2, p=1.4×10−3), D-myo-inositol (1,4,5)-triphosphate biosynthesis (PIP5K1A, PIP4K2A, p=3.4×10−3), and regulation of actin-based motility by Rho (PIP5K1A, PIP4K2A, ARPC3, p=3.6×10−3) (Figure 2, Table 3). All the genes involved in these canonical pathways are downregulated in the obese diabetics compared to the reference group and few play a role in glucose uptake (TNSK2) or in T2D signaling (PIP5K1A), (Figure 2A, 2B).

Figure 2. Top canonical pathways enriched among DEGs of morbidly obese diabetics.

A. Telomere extension by telomerase with overlay of glucose uptake function through TNSK2

B. Regulation of actin-based motility by Rho with intersection of D-myo-inositol (1,4,5)-triphosphate biosynthesis through PIP5K and interaction with type 2 diabetes signaling pathway

Table 3.

List of the most significant canonical pathways among the 68 DEGs (based on core analysis in Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA))

| Description | P-value | Molecules |

|---|---|---|

| Telomere Extension by Telomerase | 1.35E-03 | HNRNPA1,TNKS2 |

| D-myo-inositol (1,4,5)-Trisphosphate Biosynthesis | 3.36E-03 | PIP5K1A,PIP4K2A |

| Regulation of Actin-based Motility by Rho | 3.59E-03 | PIP5K1A,ARPC3,PIP4K2A |

| Rac Signaling | 6.79E-03 | PIP5K1A,ARPC3,PIP4K2A |

| RhoA Signaling | 7.38E-03 | PIP5K1A,ARPC3,PIP4K2A |

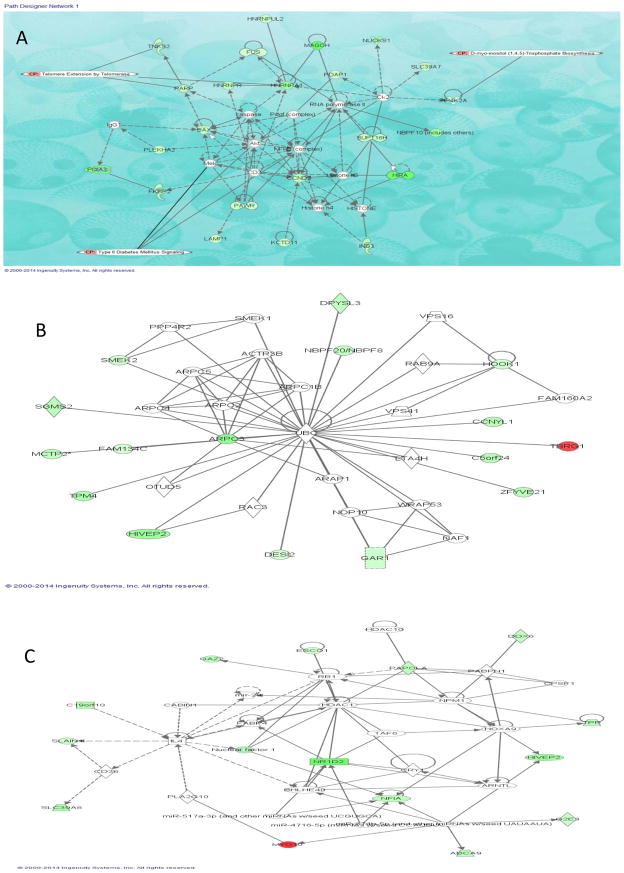

We also investigated interactions among the DEGs in morbidly obese diabetics and identified four eligible gene networks (Table 4). The three gene networks significantly overrepresented are depicted in Figure 3; the top functions of these genes are associated with infectious disease, neurological disease and cancer (Network 1, Figure 3A), dermatological diseases and conditions, developmental disorders, hereditary disorder (Network 2, Figure 3B) and RNA-post-transcriptional modification, metabolic disease, cellular development (Network 3, Figure 3C). These networks identified NF-kB, Akt and UBC as hub molecules. Although these hub molecules were not differentially expressed in this dataset, they interact directly or indirectly with number of the identified DEGs. Additionally, NF-kB and Akt are critical in insulin-induced glucose homeostasis and may play key roles in the interactions observed among the DEGs in this dataset as revealed by the overlay of type 2 diabetes canonical pathway on network 1 (Figure 3 A).

Table 4.

Biological functions and diseases associated with the top ranked networks

| Top Functions | Score | Focus Molecules | Network scheme |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infectious disease, neurological disease, Cancer | 49 | 22 | Figure 3A |

| Dermatological diseases and conditions, developmental disorder, hereditary disorder | 32 | 16 | Figure 3B |

| RNA post-transcriptional modification, metabolic disease, cellular development | 27 | 14 | Figure 3C |

| Cell-to-cell signaling and interaction, cellular assembly and organization, tissue development | 20 | 11 | - |

Figure 3. Top three networks showing interactions between selected differentially expressed genes in morbidly obese diabetics.

Red: designates transcripts up-regulated in morbidly obese/diabetic AA; green: designates transcripts down-regulated in morbidly obese/diabetic AA. White: designates transcripts not differentially expressed in our study but important in the network. The color gradient in the network indicates the strength of expression denoted by FC.

(→) indicates direct interaction between transcript products; (----->) indicates indirect interaction between transcript products; (

) indicates autoregulation.

) indicates autoregulation.

(A) Network 1 with overlay of type 2 diabetic signaling and 2 of the most significant canonical pathways observed among a number of DEGs

(B) Network 2 representing 16 of the DEGs associated with dermatological diseases and conditions as well as developmental and hereditary diseases

(C) Network 3 representing 14 of the DEGs associated with RNA post-transcriptional modifications, metabolic disease, and cellular development.

Upstream regulator analysis

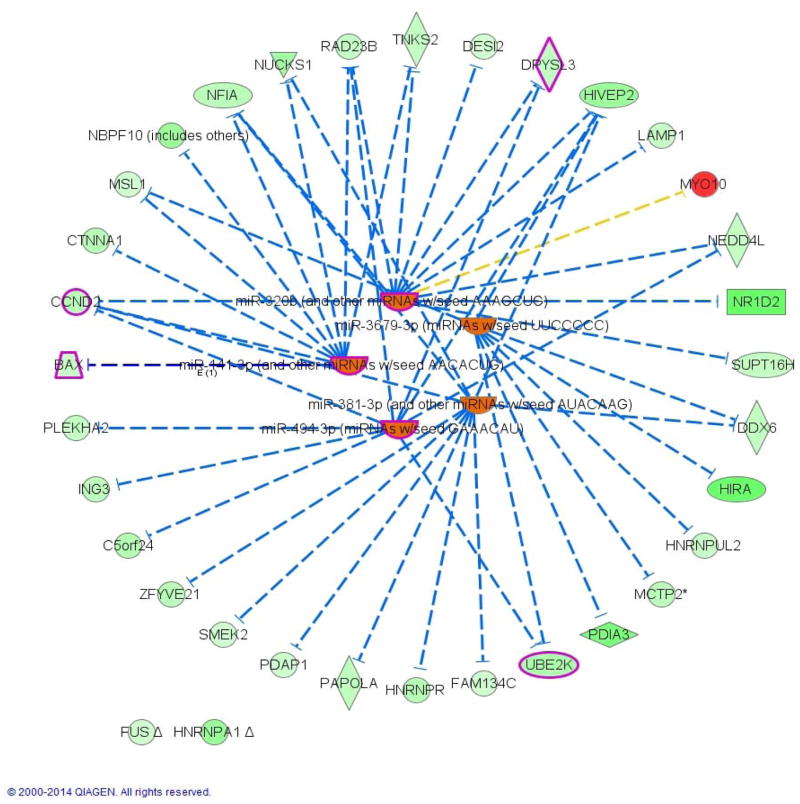

To understand the underline regulation of the expression change seen in this dataset, we used IPA upstream regulator analysis. The five most significant upstream regulators identified that would explain the gene expression changes seen were all micro RNAs (miR-320b, p= 1.20×10−6; miR-381-3p, p=2.40×10−5; miR-3679-3p, p= 9.83×10−5; miR-494-3p, p=9.98×10−5; miR-141-3p, p=1.76×10−4) and were all predicted to be activated based on the activation Z-score. Network association between the top transcriptional upstream regulators and their target genes showed that activation of the regulators resulted in downregulation of all targeted genes except for MYO10 which is up-regulated (Figure 4). Interestingly, all but 2 of the identified miRNAs notably miR-320b, miR-141-3p, miR-494-3p were previously implicated in T2D pathophysiology.

Figure 4. Upstream Analysis: Network interactions between the 5 top transcriptional regulators and their target DEGs in morbidly obese diabetics.

Orange identifies activated upstream regulators

Green identifies down-regulated target DEGs whereas red identifies up-regulated DEGs.

Blunt arrowhead indicates inhibition of the target DEG.

Purple indicates genes or regulator that overlay with T2D (4DEGs + 3 upstream regulators).

QRT-PCR validation

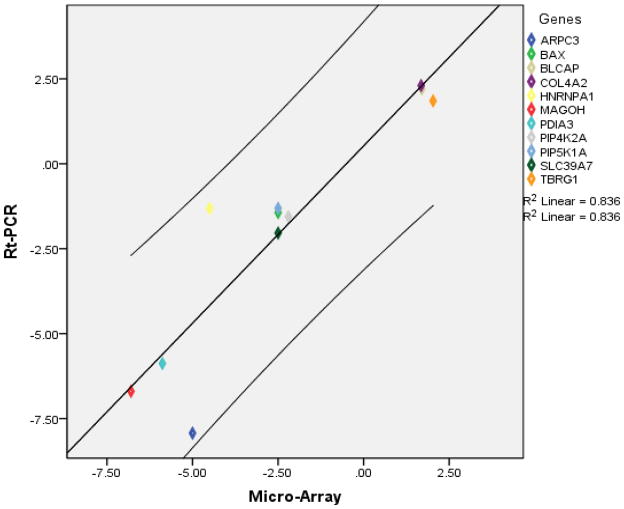

To validate our microarray data, we evaluated the expression of eleven genes selected from the microarray data using qRT-PCR. The specifics of the gene expression assays are summarized in Supplemental Table 4. Overall, the direction and magnitude of the normalized expression ratios (FC) obtained from qRT-PCR were comparable to those obtained by microarray (Supplemental Figure 1). A significant correlation of 0.82 was found among the validation dataset (Spearman’s Rho, p<0.002, n=11). Additionally a scatter plot between FC (RT-PCR) and FC (micro-array) showed a linear relation between the results from the two methods with all data points falling within the 95% confidence interval (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Scatter plot showing relationship between Micro-array and RT-PCR data for selected transcripts.

Diagonal line represents the regression line.

Discussion

We evaluated the global gene expression profile of OAT, a tissue that is recognized to play an important role in the pathophysiology of insulin resistance and T2D. We identified 68 genes, 2 upregulated and 66 downregulated, that were differentially expressed in morbidly obese African Americans with T2D compared to those that are equally obese but without T2D. MYO10 or myosin X, one of the two most upregulated gene in this study, encodes for an atypical myosin which functions as an actin-based molecular motor and plays a role in integration of F-actin and microtubule cytoskeletons during meiosis. A genome-wide association study in four European populations reported association between MYO10 variants and T2D [30]. More importantly, Zhan et al. have not only reported an association between MYO10 variants and metabolic syndrome phenotypes within an adiponectin QTL at 5p14 but also demonstrated that one of the variants had a cis-effect on MYO10 expression in peripheral white blood cells [30]. Even though the mechanisms involved remain unclear, these results suggest a role for MYO10 in the pathophysiology of T2D.

The 68 DEGs were grouped in diverse biological functions and canonical pathways. In contrast to other studies, [9] genes involved in primary metabolic processes were overwhelmingly represented among the DEGs especially those involved in RNA processing and DNA replication and repair including FUS, HNRNPA1, HNRNPR, TNKS2, and PAPOLA. RNA processing is a complicated cascade of functions that includes alternative splicing, polyadenylation, and nuclear export of mature RNA. Decreased expression of RNA processing genes in liver and skeletal muscle has been reported to contribute to metabolic phenotypes associated with obesity [31]. While downregulation of RNA processing genes (e.g. heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (HNRNPs) which encode for RNA binding proteins) has been reported to be involved in the pathobiology of obesity, to our knowledge, this study is the first to find a link between downregulation of genes involved in RNA processing and T2D in OAT. Importantly, HNRNPs are key player in the formation of spliceosomes that control alternative splicing of a number of human genes. In fact, disruption of alternative splicing has been shown in a number of disease states [31]. Several genes associated with obesity and insulin resistance, a key feature of T2D, are regulated by alternative splicing [31, 32]. Moreover, spliceosomes appear also to regulate telomeres length by modulating telomerase activity [33].

HNRPNPA1 and TNKS2, both downregulated in this study, affect telomere maintenance [34] and also belong to the telomere extension by telomerase pathway, the most significantly enriched pathway in this study. In fact, evidence implicating telomere shortening in metabolic diseases including T2D is growing [35]. Though, telomerase activity and shortening of telomeres were the most demonstrated in beta-cells and leukocytes of diabetics [36], this study reveals that such phenomenon may not just be limited to these cells types. Furthermore, TNKS are not only involved in telomere regulation but also in glucose uptake by GLUT4. TNKS knockdown in adipocytes impairs glucose uptake [37]. It has also been postulated that the association between T2D and impaired telomerase activity and regulation could also explain the occurrence of certain cancers in diabetics [38]. We observed an overlap between T2D signaling and a number of DEGs that are involved in cancer, infections and neurological diseases (Figure 3A). These interactions are mediated through factors such as NFκB, Akt, caspase known for their involvement in multiple diseases.

We also found that the biosynthesis of D-myo-inositol (1, 4, 5)-triphosphate or IP3, an important cellular second messenger, may be impaired in T2D. Two of the enzymes (PIP5K1A, PIP4K2A) responsible for IP3 synthesis are downregulated in our dataset. IP3 is involved in the release of intracellular calcium, a mechanism important for number of signaling pathways; therefore any disruption to its synthesis can potentially affect the downstream biological events such as GLUT4 vesicles trafficking that depend on intracellular calcium to maintain glucose homeostasis. Sears et al. demonstrated that in the absence of intracellular calcium both glucose transporter translocation and glucose uptake are inhibited in vitro [39]. Interestingly, D-myo-inositol (1, 4, 5)-triphosphate biosynthesis interacts with another significant canonical pathway found in this study, namely the regulation of actin-based motility by Rho through PIP2, a precursor of IP3. Both PIP2 and Arp2/3, an actin-related protein that interacts with neural Wiskott-Alrich syndrome protein (N-WASP) in the regulation of actin-based motility by Rho, control actin polymerization [40]. Arp2/3, which is downregulated in this study, participates in cortical actin regulation and translocation of GLUT4 [41, 42]. Actin remodeling has been shown to be important in the dynamics of insulin-dependent uptake of glucose into target cells by translocation of glucose transporter-4 (GLUT4) and failure in this process may result in an impaired glucose metabolism [43, 44].

Similar to previous reports [9, 19], we observed differential expression in PIP5K1A, ING3, PDIA3, transcripts involved in carbohydrates, lipids and small molecules metabolisms. Though there is a knowledge-based evidence of the potential mechanisms by which the DEGs may be involved in the pathophysiology of T2D, it is equally important to understand the underline mechanisms of regulation contributing to the gene expression change seen in this study. Hence using bioinformatics prediction, we founded that most of the DEGs identified are regulated by microRNAs which are all predicted to be in activated state and to inhibit the expression of their respective targeted transcripts. MiR-320b, miR-141-3p, miR-494-3p have been previously linked to insulin-resistance and T2D [45]. However, miR-320b’s regulation of glucose homeostasis varies with tissue type. In adipocytes, its expression is increased in insulin resistance state whereas its expression is decreased in plasma of T2D patients [46, 47]. miR-320 was shown to regulate insulin resistance in adipocytes by targeting Akt/PI3K pathways via phosphorylation of Akt and by increasing insulin-stimulated glucose uptake through increased protein expression of the glucose transporter GLUT4 [46]. To the best of our knowledge, miR-381-3p and miR-3679-3p were not previously linked to insulin resistance or T2D and would constitute novel miRNAs detected in OAT of morbidly obese diabetics and implicated in T2D [45].

The design and methods used in this study are not without limitations. One major limitation is the use of commercially acquired samples with limited phenotype data or unavailability of other biological specimens (e.g., serum and plasma) that would have allowed us assessing the association between transcript levels, protein levels and relevant phenotypes or to carry out functional assays to determine the causality of our findings. Cognizant of these limitations, we validated identified transcripts using RT-PCR. Also, this study is cross-sectional in nature and cannot infer causality. It remains imperative to replicate our findings and to determine the generalizability of these findings to other tissues (e.g., muscles) important in the pathophysiology of T2D.

In summary, this study provided key insights into gene expression patterns and pathways that distinguish between subjects with morbid obesity and diabetes versus those that are only morbidly obese. Thus, the expectation is that most of these differences are attributable to the diabetic state. Importantly the data points to the roles of: 1) RNA binding proteins (HNRNPs and TNKS) in telomere maintenance, 2) enzymes (PIP5K1A, PIP4K2A) that regulate the biosynthesis of second messenger (IP3) important in glucose homeostasis, and 3) actin remodeling (Arp3) and 4) microRNA in T2D. The study also provides a resource for future investigations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support for this study is provided by NIH grant No. 3T37TW00041-03S2 from the Office of Research on Minority Health, the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), the National Center for Research resources (NCRR) and NIDDK grant DK-54001. Expression profiling using Affymetrix HU-133 Plus 2.0 Arrays was conducted in the NHGRI microarray core facility. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the Center for Research on Genomics and Global Health. The Center for Research on Genomics and Global Health is supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Center for Information Technology, and the Office of the Director at the National Institutes of Health (Z01HG200362).

Footnotes

Duality of interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest associated with this manuscript.

References

- 1.Seidell JC. Obesity, insulin resistance and diabetes--a worldwide epidemic. Br J Nutr. 2000;83(Suppl 1):S5–8. doi: 10.1017/s000711450000088x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Dieren S, et al. The global burden of diabetes and its complications: an emerging pandemic. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 17(Suppl 1):S3–8. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000368191.86614.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogden CL, CM, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. National Center for Health Statistics. 2012:82. data brief. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shamseddeen H, et al. Epidemiology and economic impact of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Surg Clin North Am. 91(6):1163–72. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyle JP, et al. Projection of the year 2050 burden of diabetes in the US adult population: dynamic modeling of incidence, mortality, and prediabetes prevalence. Popul Health Metr. 8:29. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-8-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumanyika SK. Special issues regarding obesity in minority populations. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(7 Pt 2):650–4. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-7_part_2-199310011-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flegal KM, et al. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. Jama. 307(5):491–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boardley D, Pobocik RS. Obesity on the rise. Prim Care. 2009;36(2):243–55. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun G. Application of DNA microarrays in the study of human obesity and type 2 diabetes. Omics. 2007;11(1):25–40. doi: 10.1089/omi.2006.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takamura T, et al. Genes for systemic vascular complications are differentially expressed in the livers of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetologia. 2004;47(4):638–47. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1366-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castro-Chavez F, et al. Coordinated upregulation of oxidative pathways and downregulation of lipid biosynthesis underlie obesity resistance in perilipin knockout mice: a microarray gene expression profile. Diabetes. 2003;52(11):2666–74. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.11.2666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi K, Kim YB. Molecular mechanism of insulin resistance in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Korean J Intern Med. 25(2):119–29. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2010.25.2.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gesta S, et al. Evidence for a role of developmental genes in the origin of obesity and body fat distribution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(17):6676–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601752103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Obici S, et al. Identification of a biochemical link between energy intake and energy expenditure. J Clin Invest. 2002;109(12):1599–605. doi: 10.1172/JCI15258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Odom DT, et al. Control of pancreas and liver gene expression by HNF transcription factors. Science. 2004;303(5662):1378–81. doi: 10.1126/science.1089769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang X, et al. Microarray profiling of skeletal muscle tissues from equally obese, non-diabetic insulin-sensitive and insulin-resistant Pima Indians. Diabetologia. 2002;45(11):1584–93. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0905-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chambers JC, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies loci influencing concentrations of liver enzymes in plasma. Nat Genet. 2011;43(11):1131–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gnacińska MMS, Stojek M, Łysiak-Szydłowska W, Sworczak K. Role of adipokines in complications related to obesity. A review. Advances in Medical Sciences. 2009;54(2):150–157. doi: 10.2478/v10039-009-0035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baranova A, et al. Obesity-related differential gene expression in the visceral adipose tissue. Obes Surg. 2005;15(6):758–65. doi: 10.1381/0960892054222876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gabrielsson BG, et al. High expression of complement components in omental adipose tissue in obese men. Obes Res. 2003;11(6):699–708. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vohl MC, et al. A survey of genes differentially expressed in subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue in men. Obes Res. 2004;12(8):1217–22. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang X, et al. Evidence of impaired adipogenesis in insulin resistance. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;317(4):1045–51. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.03.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanoh Y, et al. Rosiglitazone, insulin treatment, and fasting correct defective activation of protein kinase C-zeta/lambda by insulin in vastus lateralis muscles and adipocytes of diabetic rats. Endocrinology. 2001;142(4):1595–605. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.4.8066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakoda H, et al. Dexamethasone-induced insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes is due to inhibition of glucose transport rather than insulin signal transduction. Diabetes. 2000;49(10):1700–8. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.10.1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma PM, et al. Adenovirus-mediated overexpression of IRS-1 interacting domains abolishes insulin-stimulated mitogenesis without affecting glucose transport in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17(12):7386–97. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.7386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brazma A, et al. Minimum information about a microarray experiment (MIAME)-toward standards for microarray data. Nature genetics. 2001;29(4):365–71. doi: 10.1038/ng1201-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irizarry RA, et al. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 2003;4(2):249–64. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mi H, Muruganujan A, Thomas PD. PANTHER in 2013: modeling the evolution of gene function, and other gene attributes, in the context of phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Database issue):D377–86. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Systems I. Ingenuity Upstream Regulator Analysis in IPA®. 2014:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salonen JT, et al. Type 2 diabetes whole-genome association study in four populations: the DiaGen consortium. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(2):338–45. doi: 10.1086/520599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pihlajamaki J, et al. Expression of the splicing factor gene SFRS10 is reduced in human obesity and contributes to enhanced lipogenesis. Cell Metab. 2011;14(2):208–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaminska D, Pihlajamaki J. Regulation of alternative splicing in obesity and weight loss. Adipocyte. 2013;2(3):143–7. doi: 10.4161/adip.24751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonnal S, Valcarcel J. Molecular biology: spliceosome meets telomerase. Nature. 2008;456(7224):879–80. doi: 10.1038/456879a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsai YL, et al. Involvement of replicative polymerases, Tel1p, Mec1p, Cdc13p, and the Ku complex in telomere-telomere recombination. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(16):5679–87. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.16.5679-5687.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuhlow D, et al. Telomerase deficiency impairs glucose metabolism and insulin secretion. Aging (Albany NY) 2010;2(10):650–8. doi: 10.18632/aging.100200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liew CW, Holman A, Kulkarni RN. The roles of telomeres and telomerase in beta-cell regeneration. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2009;11(Suppl 4):21–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yeh TY, et al. Insulin-stimulated exocytosis of GLUT4 is enhanced by IRAP and its partner tankyrase. Biochem J. 2007;402(2):279–90. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sampson MJ, Hughes DA. Chromosomal telomere attrition as a mechanism for the increased risk of epithelial cancers and senescent phenotypes in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2006;49(8):1726–31. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0322-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Worrall DS, Olefsky JM. The effects of intracellular calcium depletion on insulin signaling in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16(2):378–89. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.2.0776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakisaka T, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate phosphatase regulates the rearrangement of actin filaments. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17(7):3841–9. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.7.3841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jun HS, et al. High-fat diet alters PP2A, TC10, and CIP4 expression in visceral adipose tissue of rats. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16(6):1226–31. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramm G, James DE. GLUT4 trafficking in a test tube. Cell Metab. 2005;2(3):150–2. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Usui I, et al. Cdc42 is a Rho GTPase family member that can mediate insulin signaling to glucose transport in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(16):13765–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208904200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uphues I, et al. Failure of insulin-regulated recruitment of the glucose transporter GLUT4 in cardiac muscle of obese Zucker rats is associated with alterations of small-molecular-mass GTP-binding proteins. Biochem J. 1995;311(Pt 1):161–6. doi: 10.1042/bj3110161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Y, et al. HMDD v2.0: a database for experimentally supported human microRNA and disease associations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D1070–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ling HY, et al. CHANGES IN microRNA (miR) profile and effects of miR-320 in insulin-resistant 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2009;36(9):e32–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2009.05207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zampetaki A, et al. Plasma microRNA profiling reveals loss of endothelial miR-126 and other microRNAs in type 2 diabetes. Circ Res. 2010;107(6):810–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.226357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.