Abstract

Research in the 1980s pointed to the lower marriage rates of blacks as an important factor contributing to race differences in non-marital fertility. Our analyses update and extend this prior work to investigate whether cohabitation has become an important contributor to this variation. We use data from the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) and to identify the relative contribution of population composition (i.e. percent sexually active single and percent cohabiting) versus rates (pregnancy rates, post-conception marriage rates) to race-ethnic variation in non-marital fertility rates (N=7,428). We find that the pregnancy rate among single (not cohabiting) women is the biggest contributor to race-ethnic variation in the non-marital fertility rate and that contraceptive use patterns among racial minorities explains the majority of the race-ethnic differences in pregnancy rates.

Keywords: Non-marital fertility rate, Race-ethnicity, Contraception, Sexual relationship status

In the United States, race-ethnic differentials in non-marital fertility are substantial. In 2010 the non-marital fertility rate among white unmarried women ages 15–44 was 32.9 per 1,000; among black women it was about twice as high at 65.3 per 1,000. Among Hispanics, the non-marital fertility rate is even higher at 80.6 per 1,000 (Martin et al. 2012). Yet, the social factors that contribute to this differential remain unclear because the processes leading to non-marital fertility are complex. The Proximate Determinants Framework (Bongaarts 1978) is a common demographic approach to organizing this complexity by separating fertility rates into a set of necessary transitions: sexual activity, pregnancy, and pregnancy outcomes. This is useful because all social influences must work through the proximate determinants to affect fertility differentials and each proximate determinant implicates different social processes.

Our analysis combines data from the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) with a decomposition approach to identify the relative contribution of each proximate determinant to race-ethnic variation in non-marital fertility rates. To do this, the generic proximate determinants framework must be adapted. Typically, the third proximate determinant (pregnancy outcomes) is determined by miscarriage and abortion. Because survey data are not a reliable source of information on pregnancies not carried to term (Jagannathan 2001; Jones and Forrest 1992; Jones and Kost 2007), we include in our estimates of pregnancy rates only pregnancies that result in births, which we refer to as “fertile pregnancies”. Instead of reflecting the likelihood that a pregnancy results in a live birth, the third factor in this analysis incorporates marriage following a pregnancy, because not all non-marital pregnancies result in non-marital births.

This analysis extends the prior research on race-ethnic differences in the non-marital fertility rate in three ways. First, it updates a similar analysis that was conducted in the 1980s (Cutright and Smith 1988). Second, it incorporates cohabitation. About 60% of non-marital births are to unmarried couples living together (Kennedy and Bumpass 2008). An especially high proportion of minority births is to cohabiting women and some have suggested that disadvantaged and racial minority women may be using cohabitation as an alternative to marriage (Loomis and Landale 1994; Manning and Landale 1996; Martin 2002; Wildsmith and Raley 2006). Thus, cohabitation may be an important factor contributing to race-ethnic differences in non-marital fertility. Third, prior work has focused on black-white differences. The Hispanic population has increased substantially in the U.S. since 1980 (Landale and Oropesa 2007). The growth in the Hispanics combined with high rates of non-marital fertility for this population supports an extension beyond the black-white dichotomy. We also consider the nativity status of Hispanics because fertility behaviors might differ by place of birth.

Background and Conceptual Framework

As described above, the proximate determinants of non-marital fertility can be separated into three groups: those that describe sexual activity among unmarried women, those that relate to rates of pregnancy given sexual activity, and those that shape the likelihood that a non-marital pregnancy results in a non-marital birth. Below we consider the likely relevance of each of these factors to race-ethnic differences in non-marital fertility based on prior research.

Sexual Relationship Status

A small portion of race-ethnic differences in the non-marital fertility rate might be attributable to differences in sexual relationship status by race-ethnicity. Hispanic and African American teens have, on average, an earlier age at first sex compared to Non-Hispanic Whites, henceforth “whites” (Upchurch et al. 1998), but race-ethnic differentials in the timing of first sex have been declining. In 2006–2010, the percent sexually experienced for never-married white and Hispanic teens was 42, compared to 46 percent among black teens (Martinez, Copen, and Abma 2011). In addition, among teens who have ever had sex, the proportion who have had sex in the past 3 months, varies little by race-ethnicity (Martinez et al. 2011).

Differences in sexual activity are also unlikely to contribute much to black-white differentials among women in their 20s, although this may be a more important factor for the Hispanic-white gap. Whites are more likely than blacks to be currently cohabiting (Copen et al. 2012) and cohabiting women are much more likely than single women to be sexually active (Waite 1995). Yet, the proportion of unmarried women cohabiting is higher for Hispanics, especially the foreign-born, than for blacks or whites (Copen et al. 2012). Altogether this suggests that sexual relationship status is likely to be less relevant for explaining black-white differences in non-marital fertility than for Hispanic-white differential.

Fertile Pregnancy Rates by Relationship Status

In contrast to sexual activity, we anticipate that race-ethnic differences in fertile pregnancy rates among sexually active unmarried women contribute to both black-white and Hispanic-white differentials. Many factors can contribute to variability in pregnancy rates including breastfeeding and sexually-transmitted infections, but the most important one in this context is probably contraceptive use. Recent research shows that single white women have higher rates of contraceptive use than either blacks or Hispanics (Sweeney 2010), and this should result in higher pregnancy rates among black and Hispanic women. The reasons behind race-ethnic differences in contraceptive use are not clear, but prior studies have implicated socioeconomic factors, relationship context, sexual literacy (accurate knowledge about pregnancy risk, pregnancy fatalism, and perceptions of contraceptive side effects)1, fertility intentions, and access to medical professionals (Dehlendorf et al. 2010; Gaydos et al. 2010; Guzzo and Hayford 2012; Jacobs and Stanfors 2013; Shih et al. 2011).

Although this study does not attempt to explain variation in contraceptive use, our analyses investigate whether black-white and Hispanic-white differences in the non-marital fertile pregnancy rates are driven primarily by higher pregnancy rates among cohabitors, providing suggestive evidence about whether some part might be due to differences in the motivations to avoid pregnancy. Reproductive behaviors among cohabitors are an indicator of the role of cohabitation and how its meaning varies across populations (Manning and Landale 1996; Smock 2000). Some have suggested that for the disadvantaged, especially Hispanics, cohabitation may serve as an alternative to marriage (Loomis and Landale 1994; Manning and Landale 1996; Martin 2002; Wildsmith and Raley 2006). For example, cohabiting Mexican American women have higher fertility rates compared to cohabiting whites or blacks (Copen et al. 2012). Moreover, cohabitation increases planned fertility, especially among Hispanics (Musick 2002), and proportionately fewer cohabiting Hispanic women use contraception compared to cohabiting whites (Sweeney 2010). Furthermore, Mexican American women who become pregnant are more likely to continue to cohabit instead of marrying compared to blacks or whites (Choi and Seltzer 2009). Whites may be less likely to become pregnant while cohabiting and more likely to marry in response to a pregnancy because, for them, cohabitation is a short-term living arrangement that is part of the courtship process leading to marriage. Like Hispanics, blacks may consider cohabitation as a substitute for marriage since they are more likely to conceive and to give birth while cohabiting compared to whites (Loomis and Landale 1994; Manning and Landale 1996). Thus we expect that the pregnancy rate within cohabiting unions is especially important to the relatively high non-marital fertility rates of Hispanics and may contribute to black-white differences as well.

Another important question is whether race-ethnic differences in non-marital fertile pregnancy rates are largely explained by differences in contraceptive use, or if they arise from differences in miscarriage and abortion or how consistently and effectively contraception is used. Previous research suggests that black and Hispanic adolescents are less likely than whites to have used contraception at last sex (Martinez et al. 2011). In addition, among all women age 15–44 white women are significantly more likely than blacks to use a very effective method of contraception, including birth control pill or IUD (Jones, William, and Daniels 2012; Sweeney 2010). Race-ethnic gapes in contraceptive use might be especially large among single (i.e. not married or cohabiting) never married women. For example, Choi and Hamilton (2012) found that differences in contraceptive use between Mexican Americans and whites are especially pronounced among unpartnered women. More generally, other research finds that the association between marital-cohabitation status varies by race-ethnicity (Sweeney 2010). This suggests that differential patterns of contraceptive use among singles likely contribute to higher rates of non-marital fertility among blacks and Hispanics. At the same time, as mentioned above, cohabitation might serve as an alternative to marriage among blacks and Hispanics more often than for whites. If so, then race-ethnic differentials in contraceptive use patterns may be especially large among cohabitors. We are unaware of any basic descriptive analyses comparing patterns of contraceptive use among unmarried women across race-ethnic groups and our analysis addresses this gap.

Post-conception Marriage

Post-conception marriage used to be an important determinant in explaining the race-ethnic differences in non-marital fertility, but its contribution might be small today. Recent studies of historical trends indicate that declines in post-conception marriage were an important contributor to increases in premarital fertility among white and black women in the 1960s through the 1980s (England, Wu, and Shafer 2013). That downward trend continued and post-conception marriage is uncommon today. Among single (not cohabiting) women at the time of conception, only 13% of white women married prior to the birth compared to less than 5% among blacks and Hispanics. The same estimates for cohabiting women are 23 % of whites and less than 10 % among blacks and Hispanics (Lichter 2012). This suggests that although there is race-ethnic variation in post-conception marriage, it is rare for a premarital pregnancy to lead to a quick marriage even among whites. Therefore, we expect that post-conception marriage continues to contribute to racial and ethnic differences in non-marital fertility, but only in a small way.

In sum, race-ethnic differences in non-marital fertility remain large, even if they are today than they once were. The goal of this research is to understand the relative importance of relationship status, pregnancy rates, and post-marital conception to race-ethnic differentials today. An analysis of proximate determinants is a first step towards understanding the broader social and economic factors that produce race-ethnic differences in the family context of fertility.

Method

This research relies on data (female respondent file) from the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), which is a large and representative sample of the U.S. civilian, non-institutionalized population of men and women age 15–44. The 2006–2010 NSFG interviewed 12,279 women and collected detailed monthly information on fertility, relationship status (i.e., cohabitation, marriage), contraceptive use, and sexual activity for three years prior to the survey year. Because our demographic decomposition methods do not produce confidence intervals, it would be better to use data describing the entire population rather than a sample. Unfortunately, population-level data with information on cohabitation, sexual activity, and births among cohabitors is not available and so we use the NSFG, which has a large enough sample as well as the necessary information for our decomposition analysis. Our analysis uses data on the 7,426 Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic (both U.S. born and foreign born) women who were unmarried and age 15–34 in any month in the three years prior to interview.

Respondents were asked to report the date of each of their births and how many weeks they had been pregnant when their baby was born. This information is used to identify the date of conception for pregnancies ending in birth. Respondents who had ever been married were asked about the start date of their first marriage and any subsequent marital transitions, if applicable. They were also asked to give the starting and ending dates of coresidence with men whom they eventually married as well as any other male cohabiting partners. Combined with the pregnancy dates, this information allows us to determine the marital-cohabitation status at conception and childbirth.

The NSFG asks women to report on their contraceptive use in each month since the January three years prior to interview.2 Respondents who reported earlier in the interview that they had ever had sex (including all those who had been married, cohabited, or had been pregnant) were asked whether they had had any spells without sex over the past three years and to report the months in this 3–4 year period when they did not have sex.3 Using this information, along with timing of first sex, we create variables indicating respondents’ sexual activity status for each month.

We combined the information on conception, childbirth, marital-cohabitation status, and sexual-activity status to create a person-month data file describing women’s characteristics in each month for the 3–4 years prior to interview (517,203 person months). We excluded person months when sexual activity information was missing (1,259 person months). We also excluded person months lived prior to age 15 and after age 34 (151,450 person months) because having a non-marital birth is rare outside this age range4. In addition, we excluded person months in the observation window that are spent married (93,125 person months)5. If women had already been pregnant before age 15 (3 births and 6 pregnancies), these pregnancies and births were not included.

Table 1 shows the distribution of person months. Altogether, 249,418 person months are experienced by (N=7,426) unmarried women between ages 15 and 34 for the 3–4 year period preceding the interview. Of these, 58,978 person-months were spent in cohabiting relationships (not shown). The observation window included 1,267 births, 1,175 of these outside of marriage.

Table 1.

Description of Sample and Non-Marital Fertility Rate by Race/Ethnicity

| Variables | Total (15–34) |

|---|---|

| Unweighted Number of Person Months | 249,418 |

| Unweighted Number of Non-marital Fertile Pregnancies | 1,508 |

| Unweighted Number of Non-marital Fertile Pregnancies (without current pregnancies) |

1,267 |

| Unweighted Number of Non-marital Birth | 1,175 |

| Race-ethnicity (person months) | |

| White | 157,437 |

| Black | 44,597 |

| Hispanic Total | 47,385 |

| -U.S. born | 29,536 |

| -Foreign born | 17,849 |

| Non-marital Fertility Rate (weighted) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 36.76 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 96.64 |

| Hispanic Total | 84.47 |

| - U.S. born | 75.16 |

| - Foreign born | 99.87 |

| Black/White Ratio | 2.63 |

| Hispanic/White Ratio | 2.30 |

| Black/Hispanic Ratio | 1.14 |

Table 1 also describes the estimated annual non-marital fertility rate per 1,000 women ages 15–34 by race-ethnicity. This rate is estimated by dividing the number of non-marital births by the number of months (in 1,000s) that are experienced by unmarried women and multiplying by 12 (to convert monthly rates into rates per annum). Our estimates show that between age 15 and 34 the non-marital fertility rate is highest among Non-Hispanic Blacks, followed by Hispanics. Among Hispanics, the foreign-born has the highest non-marital fertility rate. We compared our estimates to those from published NCHS reports (Martin et al. 2010) and find that our estimates for whites and blacks correspond well. Our estimates for Hispanics, however, are lower than published estimates based on birth certificates6. Prior analyses also indicate that the NSFG produces lower estimates of the overall fertility rate for Hispanics compared to vital events data, although not significantly so (Martinez, Daniels, and Chandra 2012). It may be that our analyses misrepresent Hispanic-white differences in the non-marital fertility rates, but we are unable to determine whether the discrepancy between our estimates is due to error in the NSFG or error in birth certificate data.

Analytic Strategy

The non-marital fertility rate can be expressed as a function of the distribution of unmarried women by sexual relationship status, fertile pregnancy rates by sexual relationship status, and the probability of a post-conception marriage by relationship status:

Nonmarital fertility rate i = (Rsi * Ssi * Psi * Usi) + ((1 − Rsi) * Pci * Uci)

In this equation, Rs and Ss describe the proportion single among unmarried women and the proportion sexually active among single women respectively. The proportion of unmarried women that are cohabiting is expressed as 1- Rs and we assume that all cohabiting women are sexually active. Ps is the fertile pregnancy rate among sexually active single women and Pc is the fertile pregnancy rate among cohabitors. Us and Uc describe the proportion unmarried at child birth among women who became pregnant while single and cohabiting. Finally, i denotes race-ethnicity. Ideally, we would create age-specific estimates of each determinant of the non-marital fertility rate because past research found that their relative importance might vary by women’s age (Cutright and Smith 1988). Unfortunately, the number of fertile pregnancies in the 3-year window is insufficient to create reliable estimates of the fertile pregnancy rate or of marriage rates among premaritally pregnant women by age.

Measures

We began the analysis by estimating race-ethnic differences in the six determinants of non-marital fertility. The first determinant, the proportion single, was calculated by estimating the number of person-months spent single (not cohabiting) and dividing it by the total number of person-months lived unmarried. The second determinant, the proportion of singles that are sexually active, was calculated by estimating the number of person-months unmarried and not cohabiting and of these the number of person-months sexually active. The non-marital fertile pregnancy rate was calculated by dividing the number of pregnancies by the number of person-months single or cohabiting (in 1,000s) and multiplying by 12. We estimated fertile pregnancy rates counting only pregnancies that resulted in a live birth. We also estimated pregnancy rates including all pregnancies either ongoing at the time of the interview or that resulted in a live birth (not shown in here but available upon request). The two sets of estimates were essentially the same. Finally, we estimated post-conception marriage by dividing the number of premarital births by all premaritally conceived births. All of these estimates were produced from weighted data.

After creating estimates of each component of the non-marital fertility rate, we used a decomposition technique developed by Das Gupta (1993) to estimate the relative importance of each of the components to race-ethnic differences in the non-marital fertility rate. In addition, we produced estimates of contraceptive use by race-ethnicity among sexually active single and cohabiting women who are not pregnant. Respondents who ever used any method were asked to report up to four different types of contraception for each month from the January three years prior to the interview date to interview date. Respondents who never used any method were coded as “no method” in all months. In this analysis our measure of contraceptive use was based on the respondent’s report of the most effective method used and has three categories, very effective method, other method, and no method. The very effective category includes sterilization, IUD, pill, and other hormonal methods, while other method includes male and female condom, withdrawal, and other methods (Sweeney 2010; Trussell 2011).

We also estimated expected pregnancy rates by combining detailed information on contraceptive use with published estimates of pregnancy risk for typical use for each contraceptive method (See Table 1 in Trussell 2011for “failure rate”). These published estimates of pregnancy risk include all pregnancies even those not carried to term and are corrected for the underreporting of abortion in the NSFG. By comparing expected pregnancy rates to actual fertile pregnancy rates our analysis indirectly assesses the importance of contraceptive use patterns for understanding race-ethnic variation in fertile pregnancy rates.

Results

Our six determinants of the non-marital fertility rate are described in Table 2. The columns present each of the determinants and the rows represent each race-ethnic group. As can be seen from Table 2, Table 2, 77 percent of person-months lived by unmarried white women between age 15 and 34 were spent outside of a coresidential relationship. Among white singles ages 15–34, 35 percent are sexually active in a given month. About 46 non-marital pregnancies occurred annually per 1000 sexually active white singles ages 15–34, and 87 percent of these pregnancies are followed by a non-marital birth. This estimate is similar to that reported in Lichter 2012 for Non-Hispanic white women age 15–30 (87%).

Table 2.

Description of Determinants of Non-marital Fertility by Race-Ethnicity

| Singles |

Cohabitors |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportion Person Months Single |

Proportion Person- Months Sexually Active |

Annual Pregnancy Rate of Sexually Active Singles |

Proportion Unmarried at Birth |

Proportion Person- Month Cohabiting |

Annual Pregnancy Rate of Cohabitors |

Proportion Unmarried at Birth |

||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 0.77 | 0.35 | 46.45 | 0.87 | 0.23 | 127.35 | 0.83 | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.80* | 0.48* | 167.28* | 0.98 | 0.20* | 175.29* | 0.85 | |

| Hispanic Total | 0.70* | 0.35 | 139.77* | 0.95 | 0.30* | 179.67* | 0.91 | |

| U.S. Born Hispanics | 0.77 | 0.37* | 113.28* | 0.93 | 0.23 | 202.19* | 0.89 | |

| Foreign Born Hispanics | 0.60* | 0.31* | 205.47* | 0.97 | 0.40* | 157.58* | 0.94 | |

Note:

P<0.05

The reference group for the significance test for each determinant is non-Hispanic White.

The proportion sexually active among single (not cohabiting) women varies significantly across race-ethnic groups, with blacks more likely to be sexually active compared to whites and Hispanics. Higher levels of cohabitation among white and Hispanic women, especially foreign-born Hispanic women, offset the relatively high levels of sexual activity among black singles so that the percent sexually active among all unmarried women is similar across race-ethnic groups. For white women, 50 percent (.77*.35+.23) of the person-months unmarried are sexually active compared to 55 % for Hispanics (51% for the U.S.-born, 58% for the foreign-born) and 58% for blacks.

Non-marital fertile pregnancy rates for sexually active singles and cohabitors are significantly higher for blacks and Hispanics than for whites. Fertile pregnancy rates are higher for cohabitors than sexually active singles across all race-ethnic groups except foreign-born Hispanics. Lastly, the marriage rate following a non-marital pregnancy for both singles and cohabitors is low across all race-ethnic groups, and differences are often not statistically significant.

Table 3 presents the results of the decomposition of the non-marital fertility rates. Each number represents the proportion of the racial-ethnic difference that is due to a specific factor, and these numbers sum to 1. For example, the 0.64 in the non-marital pregnancy rate among singles row indicates that 64% of the black-white difference in the non-marital fertility rate is due to black-white differences in the non-marital pregnancy rate among sexually active single women. The higher levels of sexual activity among black singles accounts for 17 % of the gap, but this is somewhat offset (− 4%) by lower levels of cohabitation among blacks. Higher fertile pregnancy rates among cohabiting blacks also contribute slightly (14%) to the black-white gap. Overall, the results indicate that by far the biggest contributor to the black-white gap in the non-marital fertility rates is differences in the non-marital pregnancy rate among sexually active single women. In contrast, post-conception marriage contributes very little (overall 7+1=8%) to black-white differences in non-marital fertility.

Table 3.

Decomposition of Race-ethnic Differences in Non-Marital Fertility by Six Determinants

| Hispanic vs. White |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black vs. White |

Hispanic Total vs. White |

U.S. born vs. White |

Foreign born vs. White |

|

| (1) Proportion Single/Cohabiting | −0.04 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.24 |

| (2) Proportion Sexually Active among Singles | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.05 |

| Sexually Active Singles | ||||

| (3) Non-marital Fertile Pregnancy Rate | 0.64 | 0.48 | 0.45 | 0.55 |

| (4) Proportion Unmarried at Birth | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 |

| Cohabitation | ||||

| (5) Non-marital Fertile Pregnancy Rate | 0.15 | 0.26 | 0.41 | 0.14 |

| (6) Proportion Unmarried at Birth | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.08 |

| Total | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

The right three columns of Table 3 show the results of the decomposition of differences between Hispanic and white women. Interestingly, the decomposition results differ substantially by Hispanic women’s nativity status. The pregnancy rates for cohabitors as well as singles are the most important contributors to U.S. born Hispanic-white differences in the non-marital fertility rate. In contrast, the non-marital pregnancy rate among singles accounts for more than half foreign born Hispanic-white gap, while the non-marital pregnancy rate among cohabitors contributes only 14% of this gap. In addition, unlike U.S. born Hispanic-white differences, the proportion cohabiting is the second biggest contributor to the foreign born Hispanic-white gap. That is, foreign-born Hispanic women are more likely than white women to be cohabiting and cohabitors tend to have higher non-marital pregnancy rates than singles, but among cohabitors the pregnancy rates of the foreign-born are not enough higher than for whites to contribute much to the overall differential in the non-marital fertility rate.

Altogether, these results show that in 2006–2010 sexual activity and marriage following a non-marital pregnancy are no longer major contributors in racial differences in the non-marital fertility rate. Cohabitation contributes somewhat. For US-born Hispanics, this is because fertility rates among cohabitors are higher than whites. For foreign-born Hispanics, it is because of high proportions cohabiting. Yet, even more important than pregnancy rates among cohabitors is the pregnancy rate among sexually active singles.

Next, to further understand race-ethnic differences in pregnancy rates among sexually active unmarried women, we examine patterns of contraceptive use. Prior research indicates that black and Hispanic women are more likely than white women to not use any method of contraception (Frost, Singh, and Finer 2007; Mosher and Jones 2010), and Sweeney (2010) employed multivariate regression techniques to show that race-ethnic differences in contraceptive use are larger for singles than married women. Taken together these results suggest that white unmarried women are more likely than blacks and Hispanics to use contraception, but the magnitude of the differences or how closely they correspond to race differences in non-marital pregnancy rates is unknown.

Table 4 presents patterns of contraceptive use among sexually active single and cohabiting women who are not pregnant. Across all race-ethnic groups, the majority of unmarried women use some form of contraception. Nonetheless, race-ethnic differences in contractive use are large, significant, and consistently in the direction of elevating minority women’s risk of pregnancy relative to white women. Among sexually active single women, for example, 5 percent of white women use no contraception compared to 18 percent of black women and 17 percent of Hispanic women. The contraceptive use patterns are similar between U.S.-born and foreign-born Hispanic women. Levels of contraceptive use are lower among cohabitors compared to sexually active singles, across all race-ethnic groups. This likely accounts for some of cohabitors’ much higher pregnancy rates (Table 2), but contraceptive use patterns are only one of potentially many factors leading to race-ethnic variation in fertile pregnancy rates. Infecundity, frequency of sexual activity, consistency of contraceptive use, as well as abortion can also contribute, but we do not have as good data on these factors.

Table 4.

Description of Contraceptive Use Patterns among Unmarried Women at Risk of Pregnancy

| Sexually Active Single |

Cohabitor |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contraceptive Use | No Contraceptive Method |

Very Effective Contraceptive Method |

Other Contraceptive Method |

Row Total |

No Contraceptive Method |

Very Effective Contraceptive Method |

Other Contraceptive Method |

Row Total |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 0.05 | 0.66 | 0.29 | 1.00 | 0.17 | 0.61 | 0.22 | 1.00 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.18* | 0.42* | 0.40* | 1.00 | 0.38* | 0.40* | 0.23 | 1.00 |

| Hispanic Total | 0.17* | 0.42* | 0.40* | 1.00 | 0.31* | 0.48* | 0.21 | 1.00 |

| U.S. born Hispanics | 0.16* | 0.41* | 0.43* | 1.00 | 0.29* | 0.45* | 0.25* | 1.00 |

| Foreign born Hispanics | 0.17* | 0.44* | 0.39* | 1.00 | 0.31* | 0.51* | 0.18* | 1.00 |

Note:

P < 0.05

The reference group for the significance test is non-Hispanic white.

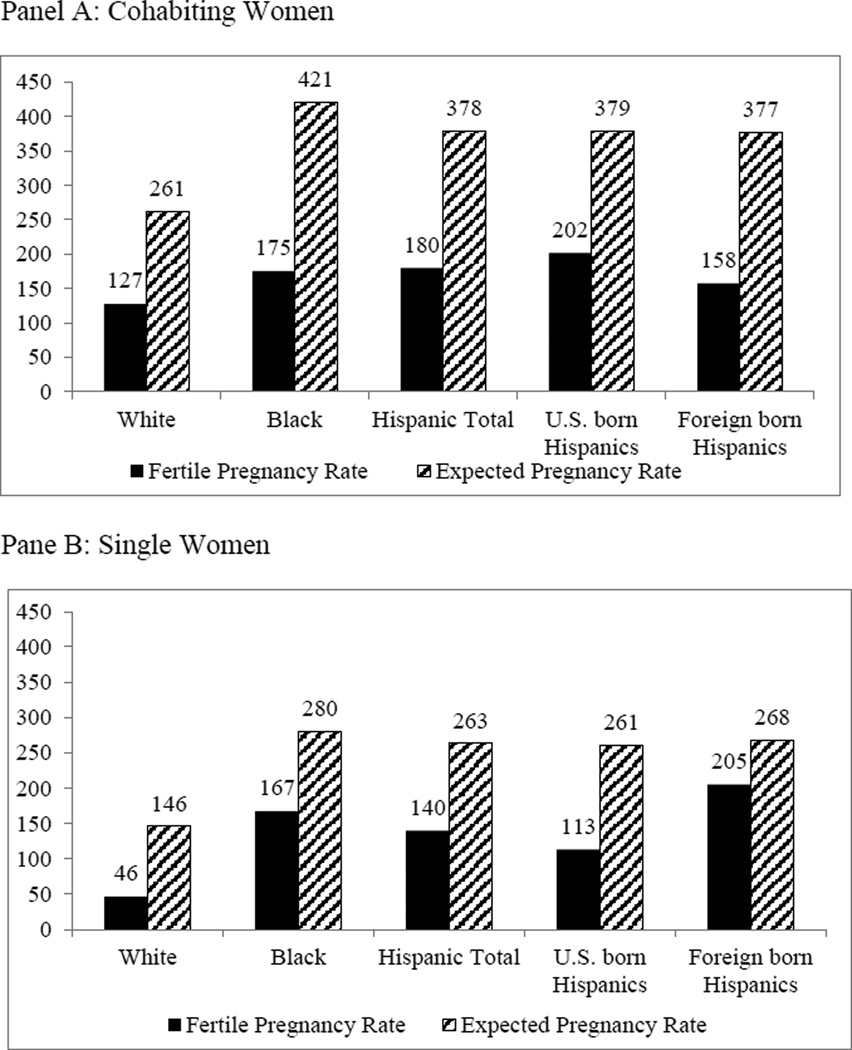

To indirectly address the potential role of these other factors in the non-marital pregnancy rates and to summarize the implications of the reported contraceptive patterns in Table 4, Figure 1 describes race-ethnic variation in the fertile pregnancy rates and expected pregnancy rates (per 1000 women) given contraceptive use patterns among sexually active unmarried women and typical pregnancy rates for women using each type of contraceptive method. Solid bars denote the fertile pregnancy rates and diagonal line bars represent the expected pregnancy rates given patterns of contraceptive use and failure rates for typical use of each type of contraception. The clearest finding from Figure 1 is that patterns of reported contraceptive use lead to substantial race-ethnic differences in expected pregnancy rates among both cohabitors and singles. Among singles, the diagonally-striped bars are almost twice as tall for blacks and Hispanics compared to whites.

Figure 1.

Fertile Pregnancy Rates and Estimated Pregnancy Rates by Race-Ethnicity and Relationship Status (per 1,000 women)

Panel A: Cohabiting Women

Pane B: Single Women

If pregnancy rates were purely a function of reported levels of contraceptive use, the differences between the solid and stripped bars would represent pregnancies ending in miscarriage and abortion. Focusing first on cohabiting women, we see that for whites the fertile pregnancy rate is about half (127/261=.49) the expected pregnancy rate based on contraceptive use patterns. The ratio is slightly higher for US-born (.52) Hispanic women and slightly lower for black (.42) and foreign-born Hispanic (.42) women. That the ratio is roughly similar across all groups suggests that differential rates of miscarriage and abortion are not contributing much to race-ethnic differences in the non-marital pregnancy rate among cohabitors.

Among sexually active singles, however, the ratio is much smaller for white women (.32) compared to black (.60) and Hispanic (.53) women, especially for foreign-born Hispanics (.76). This suggests that higher levels of abortion among white women could be an important contributing factor to their lower non-marital pregnancy rate. This interpretation assumes, however, that contraceptive use patterns are equally well reported across race-ethnic groups and that race-ethnic differences in consistency of use are also small. Forming hard conclusions about the role of abortion is difficult in the absence of good data on pregnancies not carried to term. Nonetheless, the analysis presented here provides good support for the conclusion that contraceptive use patterns are responsible for a large part of race-ethnic differences in the non-marital pregnancy rates.

Discussion and Conclusion

The main goal of this paper was to examine the relative importance of relationship status, pregnancy rates, and post-conception marriage to race-ethnic differences in non-marital fertility in 2006–2010. This effort represents an update of prior work and an extension to incorporate cohabitation and consider fertility patterns among Hispanics. Our analysis provides us with several findings. First, today variation in sexual activity and in post-conception marriage contributes little to racial differences in non-marital fertility. Second, cohabitation plays a smaller role than we anticipated. Even among U.S.-born Hispanics, pregnancy rates among sexually active singles were as important as rates among cohabitors, but for blacks and foreign-born Hispanics cohabitation clearly has a secondary role.

These findings may be in some ways surprising given all the attention demographers have paid to the importance of cohabitation for non-marital fertility trends and a common perception that cohabitation might serve as an alternative to marriage for minority women, especially Hispanic women. Yet, over the past 30 years as the non-marital fertility rates have been rising for whites, they have not increased for blacks or Hispanics. The increase in non-marital fertility over this time was largely due to increases in cohabitation among white women (Raley 2001), which greatly diminished race-ethnic variation in non-marital sexual activity. Declines in post-conception marriage led to rises in non-marital fertility among both whites and blacks in earlier parts of the century (England, Wu, and Shafer 2013), but postmarital conception was already rare among blacks by 1980. Since then, whites and Hispanics have been catching up (Bachu 1999) so that today race-ethnic differentials in post-conception marriage are relatively small (Lichter 2012). As race-ethnic differences in sexual activity and post-conception marriage diminished, differences in fertile pregnancy rates became the most important factor suppressing white non-marital births.

Today black-white differences in the non-marital fertility rates are driven largely by differences in the pregnancy rates among sexually active singles. Our analyses suggest these differences are largely due to patterns of contraceptive use. Lower abortion rates among black and Hispanic unmarried pregnant women might contribute somewhat to their higher fertile pregnancy rates, but variation in contraceptive use is more than sufficient to explain race-ethnic differences.

Like other studies, this study has some limitations. First, even among individuals who are sexually active in a given month, the frequency of sexual intercourse varies by each individual. Therefore, we may be underestimating the importance of sexual activity, although there is no reason to expect race-ethnic differences in sexual frequency in a given month. Second, our measures of contraceptive use are likely imperfect. Women are asked to retrospectively report their method for up to four years prior to the survey. For women who use the same method throughout the study this might not be challenging, but those who are in multiple relationships or who change methods frequently might not be able to provide accurate reports. Moreover, individuals using contraception do not necessarily use it consistently or correctly. Compared to whites, blacks and US-born Hispanics report less consistent contraceptive use among women using the pill, but this difference was not statistically significant (Frost and Darroch 2008). Third, we do not have good data on pregnancies not carried to term. Thus, it is impossible to definitively identify how much variation in pregnancy rates among singles or cohabiting women is due to contraception and how much to miscarriage or abortion. Lastly, we could not include Asians or other groups (e.g. American Indians) in our analysis since the NSFG combines all race-ethnic groups other than white, black, and Hispanic into an “other” category. Not including Asians does not affect our conclusions regarding differences whites, blacks, and Hispanics, but fertility patterns of Asians differ from other minority women. According to the NCHS report, the non-marital fertility rate for Asians or pacific islanders in 2010 was 22.3 per 1000 women while the corresponding rate for non-Hispanic whites was 32.9 (Martin et al. 2012). Thus, minority status per se does not always lead to higher non-marital fertility rates and our conclusion that differences in sexual activity or post-conception marriage are not important cannot be extended to Asians.

Despite these limitations, this paper locates the most important determinant of race-ethnic differences: contraceptive use among sexually active single women. Whereas levels of sexual activity and post-conception marriage were once major contributors to race-ethnic differences in the non-marital fertility rate (Cutright and Smith 1988), today the picture is much simpler. This is important because it suggests that reducing race-ethnic differences in contraceptive use among unmarried women, especially those who are not cohabiting, could have a major impact on race-ethnic differences in the non-marital fertility rate.

Explaining race-ethnic variation in contraceptive use is beyond the scope of this study (see Sweeney and Raley (2014) for a fuller treatment). One possibility is raised by Gray, Stockard, and Stone (2006) who argue that the rise in non-marital fertility rates7 could be due to declines in marriage. They posit that increases in the unmarried population increase non-marital birth rates by changing the composition of the unmarried population so that it includes more women with a high desire to have children. Because black women have lower proportions of women married, this argument could be applied to black-white differences in non-marital fertility. Specifically, our analysis shows that unmarried white women are more likely to use (effective) contraception than black women. It could be that matching the group of unmarried black women not using contraception there is a group of white women with high propensities for fertility (and low probabilities of using contraception) that we do not observe because they are married. To distort our results in the way that the GSS model predicts these women would have to keep these high propensities for fertility (and low contraceptive use) even in the hypothetical situation that they were not married. It seems likely to us that women’s propensity for fertility is affected by their marital status, but to the extent that women have an underlying propensity for fertility that does not respond to marital status, selection into marriage could distort our results. Unfortunately, we are unable to identify the extent to which this might affect our results because we have no way to measure this underlying propensity for fertility (see Ermisch (2009) and Wu (2009) for additional formal critiques of Gray et al. 2006).

Related, the evidence provided here does not support the idea that race-ethnic differences in non-marital fertility rates arise because of a higher desire for children or lower motivations to avoid non-marital pregnancies. If we had found that race-ethnic differences were most prominent among cohabitors, then higher non-marital fertility rates among minority women could be because cohabitation is serving as an alternative to marriage, one where childbearing is normative. This is not what we found, however. Single not-cohabiting women are the group that contributes most to racial variation, the group for whom non-marital fertility is least likely to be intended. Moreover, unmarried black women are more likely than white women to report that they would be very upset by an unintended pregnancy (Hayford and Guzzo 2013).

Future research should further investigate the association between relationship status and fertility intentions and how this varies by race-ethnicity, but researchers should also attend more to the structural barriers to contraceptive access and the relationship context of minority women. Some research points to economic barriers to access to highly effective contraceptive methods (Mestad et al. 2011; Secura et al. 2010), but more research using population-representative data is needed. It is not clear whether unmarried not-cohabiting blacks and Hispanics are more likely than similar whites to have unstable relationships, but if they do, high levels of relationship instability might make it less attractive to use highly effective long-lasting contraception such as the pill. Women with unstable relationships may be less able to plan sexual intimacy and need to negotiate contraceptive use with each new partner. This, combined with concerns about STIs increases the appeal of condoms (Jacobs and Stanfors 2013) relative to long-lasting methods, including IUD, or injectables (Glei 1999). Although condoms reduce the risk of STIs and are easy to obtain (no prescription or doctor visit required), they require men’s cooperation and people do not always have them available (Glei 1999). Together these factors may work to lower the use of highly effective coitus-independent methods and perhaps also lead to inconsistent use of condoms, ultimately increasing the risk of unintended pregnancies. The results of this study make clear that understanding race-ethnic variation in non-marital fertility requires greater attention to the sources of race-ethnic variation in contraceptive use, especially among single women.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by continuing fellowship from the Department of Sociology at the University of Texas at Austin and also benefitted from 5 R24 HD042849, Population Research Center, awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Health and Child Development. Opinions reflect those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the granting agency.

Footnotes

For example, black and Hispanic women are more likely to underestimate the effectiveness of the birth control pill, and black women express greater fear of side effects of hormonal contraception, including reduced sexual desire, elevated risk of cancer, and permanent sterility (Guzzo and Hayford 2012)

The specific wording of the question, asked of anyone who has ever used contraception, is as follows: The next questions are about birth control methods you may have used between (START DATE OF METHOD CALENDAR) and (END DATE OF METHOD CALENDAR). Remember that this also refers to methods men use, such as condoms, vasectomy, and withdrawal. As we discussed earlier, you had a hysterectomy in (DATE OF HYSTERECTOMY). Since (START DATE OF METHOD CALENDAR), have you used any birth control methods for any reason, such as preventing disease?

The specific question on sexual activity during the three-plus years prior to interview reads: Since (January [YEAR OF INTERVIEW-3]/[DATE OF FIRST SEX]), have there been any times when you were not having intercourse with a male at all for one month or more. It is asked only of respondents who report having ever had sex in earlier parts of the interview.

The non-marital fertility rate for women ages 35–39 is 29.6 per 1000 women in 2010, and the corresponding figure for women ages 40–44 is 8.0 (Martin et al 2012). The substance of our findings is the same regardless whether we exclude or include women ages 35 and above.

Person-months separated, divorced, and widowed are included.

We are unaware of any published estimates of the non-martial fertility rate for Hispanics by nativity status.

Note that the Gray et al. (2006) article is mostly about the non-marital fertility ratio, but we focus on the parts of their argument that apply most to the non-marital fertility rate.

The published version of this article is available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11113-014-9342-9 http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11113-014-9342-9

References

- Bachu A. Trends in Premarital Childbearing: 1930 to 1994. US Census Bureau: US Dept. of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts John. A Framework for Analyzing the Proximate Determinants of Fertility. Population and pand development review. 1978:105–132. [Google Scholar]

- Choi Kate H, Hamilton Erin R. Mexican Migration to the United States and Family Planning. in. San Francisco, CA: Presented at the Population Association of America Annual Meetings; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Choi Kate, Seltzer Judith. Race, Ethnic, and Nativity Differences in the Demographic Significance of Cohabitation in Women’s Lives. California Center for Population Research, University of California-Los Angeles; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Copen Casey E, Daniels Kimberly, Vespa Jonathan, Mosher William D. First Marriages in the United Staes: Data from the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. National Center for Health Statistics. Division of Vital Statistics. 2012:49. Number. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutright P, Smith HL. Intermediate Determinants of Racial-Differences in 1980 United-States Nonmarital Fertility Rates. Family Planning Perspectives. 1988;20:119–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehlendorf Christine, Ruskin Rachel, Grumbach Kevin, Vittinghoff Eric, Bibbins-Domingo Kirsten, Schillinger Dean, Steinauer Jody. Recommendations for Intrauterine Contraception: A Randomized Trial of the Effects of Patients’ Race/Ethnicity and Socioeconomic Status. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2010;203:319. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.05.009. e1–319. e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England Paula, Wu Lawrence L, Shafer Emily Fitzgibbons. Cohort Trends in Premarital First Births: What Role for the Retreat from Marriage? Demography. 2013;50:2075–2104. doi: 10.1007/s13524-013-0241-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermisch John. The Rising Share of Nonmarital Births: Is It Only Compositional Effects? Demography. 2009;46:193–202. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost Jennifer J, Darroch Jacqueline E. Factors Associated with Contraceptive Choice and Inconsistent Method Use, United States, 2004. Perspectives on sexual and reproductive health. 2008;40:94–104. doi: 10.1363/4009408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost Jennifer J, Singh Susheela, Finer Lawrence B. Factors Associated with Contraceptive Use and Nonuse, United States, 2004. Perspectives on sexual and reproductive health. 2007;39:90–99. doi: 10.1363/3909007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaydos Laura M, Neubert Berivan Demir, Hogue Carol JR, Kramer Michael R, Yang Zhou. Racial Disparities in Contraceptive Use between Student and Nonstudent Populations. Journal of Women’s Health. 2010;19:589–595. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glei Dana A. Measuring Contraceptive Use Patterns among Teenage and Adult Women. Family Planning Perspectives. 1999:31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray Jo Anna, Stockard Jean, Stone Joe. The Rising Share of Nonmarital Births: Fertility Choice or Marriage Behavior? Demography. 2006;43:241–253. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta Prithwis Das. Standardization and Decomposition of Rates: A User’s Manual. Bureau of the Census: US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo Karen Benjamin, Hayford Sarah. Race-Ethnic Differences in Sexual Health Knowledge. Race and social problems. 2012;4:158–170. doi: 10.1007/s12552-012-9076-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayford Sarah R, Guzzo Karen Benjamin. Racial and Ethnic Variation in Unmarried Young Adults’ Motivation to Avoid Pregnancy. Perspectives on sexual and reproductive health. 2013;45:41–51. doi: 10.1363/4504113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs Josephine, Stanfors Maria. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Us Women’s Choice of Reversible Contraceptives, 1995–2010. Perspectives on sexual and reproductive health. 2013;45:139–147. doi: 10.1363/4513913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagannathan R. Relying on Surveys to Understand Abortion Behavior: Some Cautionary Evidence. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:1825–1831. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EF, Forrest JD. Underreporting of Abortion in Surveys of United-States Women - 1976 to 1988. Demography. 1992;29:113–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones Jo, William Mosher, Daniels Kimberly. Current Contraceptive Use in the United States, 2006–10, and Changes in Patterns of Use since 1995. Hyattsville, MD: 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RK, Kost K. Underreporting of Induced and Spontaneous Abortion in the United States: An Analysis of the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Studies in Family Planning. 2007;38:187–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2007.00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy S, Bumpass L. Cohabitation and Children’s Living Arrangements: New Estimates from the United States. Demographc Research. 2008;19:1663–1692. doi: 10.4054/demres.2008.19.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landale NS, Oropesa RS. Hispanic Families: Stability and Change. Annual Review of Sociology. 2007;33:381–405. Annual Review of Sociology. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter Daniel T. Early Adulthood in a Family Context. Springer; 2012. Childbearing among Cohabiting Women: Race, Pregnancy, and Union Transitions; pp. 209–219. [Google Scholar]

- Loomis Laura Spencer, Landale Nancy S. Nonmarital Cohabitation and Childbearing among Black and White American Women. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1994:949–962. [Google Scholar]

- Manning Wendy D, Landale Nancy S. Racial and Ethnic Differences in the Role of Cohabitation in Premarital Childbearing. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1996:63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Martin Joyce A, Hamilton Brady E, Ventura Stephanie J, Osterman Michelle JK, Wilson Elizabeth C, Mathews TJ. National vital statistics reports. Vol. 61. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. Births: Final Data for 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin Joyce A, Hamilton Brady E, Sutton Paul D, Ventura Stephanie J, Mathews TJ, Kimeyer Sharon, Osterman Michelle J.K. Birth: Findal Data for 2007 National Vital Statistics Reports. 24. Vol. 58. U.S. Department of Health and Human Service; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin Teresa Castro. Consensual Unions in Latin America: Persistence of a Dual Nuptiality System. Journal of comparative family studies. 2002:35–55. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Gladys, Copen Casey E, Abma Joyce C. Teenagers in the United States: Sexual Activity, Contraceptive Use, and Childbearing, 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. National Center for Health Statistics. 2011;23(31) Vital Health Stat. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Gladys, Daniels Kimberly, Chandra Anjani. Fertility of Men and Women Aged 15–44 Years in the United States: National Survey of Family Growth, 2006–2010. National health statistics reports. 2012:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mestad Renee, Secura Gina, Allsworth Jenifer E, Madden Tessa, Zhao Qiuhong, Peipert Jeffrey F. Acceptance of Long-Acting Reversible Contraceptive Methods by Adolescent Participants in the Contraceptive Choice Project. Contraception. 2011;84:493–498. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher William D, Jones Jo. Use of Contraception in the United States: 1982–2008. Vital and health statistics Series 23, Data from the National Survey of Family Growth. 2010:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musick K. Planned and Unplanned Childbearing among Unmarried Women. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:915–929. [Google Scholar]

- Raley RKelly. Increasing Fertility in Cohabiting Unions: Evidence for the Second Demographic Transition in the United States? Demography. 2001;38:59–66. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secura Gina M, Allsworth Jenifer E, Madden Tessa, Mullersman Jennifer L, Peipert Jeffrey F. The Contraceptive Choice Project: Reducing Barriers to Long-Acting Reversible Contraception. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2010;203:115. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.04.017. e1–115. e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih Grace, Vittinghoff Eric, Steinauer Jody, Dehlendorf Christine. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Contraceptive Method Choice in California. Perspectives on sexual and reproductive health. 2011;43:173–180. doi: 10.1363/4317311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smock Pamela J. Cohabitation in the United States: An Appraisal of Research Themes, Findings, and Implications. Annual Review of Sociology. 2000:26. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney Megan M. The Reproductive Context of Cohabitation in the United States: Recent Change and Variation in Contraceptive Use. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:1155–1170. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney Megan M, Raley RKelly. Race, Ethnicity, and the Changing Context of Childbearing in the United States. Annual Review of Sociology. 2014:40. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trussell James. Contraceptive Failure in the United States. Contraception. 2011;83:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upchurch Dawn M, Levy-Storms Lene, Sucoff Clea A, Aneshensel Carol S. Gender and Ethnic Differences in the Timing of First Sexual Intercourse. Family Planning Perspectives. 1998:30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite Linda J. Does Marriage Matter? Demography. 1995;32:483–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildsmith Elizabeth, Raley RKelly. Race Ethnic Differences in Nonmarital Fertility: A Focus on Mexican American Women. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68:491–508. [Google Scholar]

- Wu Lawrence L. Composition and Decomposition in Nonmarital Fertility. Demography. 2009;46:209–210. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]