Abstract

The primary aim of the current study was to examine self-criticism as a potential mechanism mediating the relation between mothers' own childhood maltreatment history and changes in subsequent maternal efficacy beliefs in a diverse sample of low-income mothers with and without Major depressive disorder (MDD). Longitudinal data were drawn from a larger randomized clinical trial evaluating the effectiveness of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) for depression among low-income mothers and their 12-month old infant (see Toth, Rogosch, Oshri, Gravener-Davis, Sturm, & Morgan-Lopez; 2013). Results indicated that higher levels of maltreatment in childhood led mothers to hold more self-critical judgments in adulthood. Additionally, mothers who had experienced more extensive childhood maltreatment histories perceived themselves as less efficacious in their role as mother. Structural equation modeling indicated that self-criticism mediated the relationship between childhood maltreatment and mothers' decreased perceived competency in her maternal role from when her child was an infant to the more demanding toddler years. Finally, this relationship held over and above the influence of mothers' depressive diagnostic status. Directions for future research and the clinical implications of these findings are discussed.

Keywords: childhood maltreatment, maternal efficacy, self-criticism, depression, parenting

Introduction

Parenting is unquestionably a challenging role, placing significant emotional, physical, and intellectual demands on both mothers and fathers. Parenthood requires a high level of commitment to protect and nurture one's children over an extended period of time, thus requiring tremendous amounts of parents' time and energy. Many parents are able to face such challenges and they experience parenthood as gratifying. Yet, it is not uncommon for some parents to feel overly burdened by the demands of childcare and perceive little of what they do as pleasurable. This despondency in its extreme form may result in the psychological unavailability of primary caregivers, which has been shown to operate as a precursor of child maltreatment (Egeland & Sroufe, 1981; Erickson & Egeland, 1987; Mrazek, 1993).

Parental efficacy beliefs, or the degree to which parents perceive themselves as able to master the varied tasks associated with this demanding role, have emerged as a strong, direct predictor of positive parenting practices (Ardelt & Eccles, 2001; Izzo et al., 2000) and a mediator of other variables related to parenting quality such as maternal depression, child temperament, social support, and poverty (Coleman & Karraker, 1998). Parents must possess the following to feel efficacious: (1) knowledge of the appropriate childcare responses, (2) confidence in their own ability to accomplish such tasks, and (3) the belief that their children will respond contingently, and that others in their social environment (i.e., family and friends) will be supportive of those efforts (Coleman & Karraker, 1998). Some also conceptualize parental efficacy as parents' perceived ability to positively influence the behavior and development of their children (Coleman & Karraker 2003). Thus, it is conceivable that parental efficacy beliefs may be increasingly challenged as infants enter toddlerhood and acquire more behaviors that require management (e.g., increased mobility, etc.). Mothers' self-efficacy has been shown to influence their motivation to engage in challenging tasks, such as more promotive and preventive parenting strategies (Ardelt & Eccles, 2001; Elder et al., 1995). Promotive strategies strive to create positive child experiences or help a child to develop skills and interests, while preventive parenting strategies have the goal of reducing child risk and adverse outcomes (Jones & Prinz, 2005). Parents with low levels of perceived efficacy may then be more likely to control child behavior with more forceful techniques such as spanking and/or yelling (Coleman & Karraker, 1998). In fact, numerous studies by Bugental and colleagues (Bugental, Blue, & Lewis, 1990; Bugental & Cortez, 1988; Bugental & Shennum, 1984) suggest that low maternal efficacy is associated with the tendency to focus on relationship difficulties, negative affect, elevated autonomic arousal, feelings of helplessness in the parenting role, and use of coercive discipline. In addition, MacPhee and colleagues (1996) found that, among a large sample of ethnically diverse low-income parents, higher parental efficacy beliefs were strongly related to more positive parental limit setting and less harsh disciplinary practices. Yet, what factors influence a parent's sense of efficacy?

Given research showing that a parent's sense of self-efficacy is closely intertwined with parenting quality (Coleman & Karraker, 1998), surprisingly little is known about how parenting attitudes and perceptions differ among parents with and without histories of maltreatment, and if efficacy beliefs play a role in the intergenerational transmission of such abuse. Child maltreatment is a pervasive societal problem that often leads to harmful negative effects on children, not only during childhood, but also across the lifespan (e.g., Cicchetti & Toth, 2015). In considering the etiology of child maltreatment, much attention has been focused on reports linking parents' own problematic child-rearing histories with their subsequent, often abusive, parenting (Belsky, Jaffee, Sligo, Woodward, & Silva, 2005; Cort, Toth, Cerulli, & Rogosch, 2011; DiLillo & Damashek, 2003; Friesen, Woodward, Horwood, & Fergusson, 2013; Neppl, Conger, Scaramella, & Ontai, 2009; Widom, Czaja, & DuMont, 2015). While there is some empirical evidence showing lower maternal efficacy in mothers with histories of abuse (Fitzgerald et al., 2005), most research done in this area has focused solely on individuals with histories of child sexual abuse (CSA) (DiLillo & Damashek, 2003). Both clinical and empirical reports suggest that mothers with a history of sexual abuse perceive themselves as less competent and efficacious mothers and report greater parenting difficulties than non-abused mothers (Fitzgerald et al., 2005). They also report feeling more stressed, disorganized, inconsistent, and less emotionally controlled in child rearing (Cohen, 1995; Cole, Woolger, Power, & Smith, 1992; Douglas, 2000).

Importantly, empirical work indicates that parental competency beliefs are particularly salient under disadvantaged ecological conditions where the risk for child maltreatment is increased (Bandura, 1995; Halpern, 1993). More specifically, research has demonstrated that psychological risk in economically disadvantaged, inner city children can be greatly reduced when nurturing parents are able to maintain a sense of personal efficacy in the parental role despite the adverse environmental circumstances with which they are confronted (Elder, 1995). Therefore, identifying factors associated with the development of maladaptive parenting beliefs and behaviors is critical to facilitate the targeting of prevention and intervention programs towards parents with histories of maltreatment. Yet, the potential underlying mechanisms influencing the association of child maltreatment history and low parental efficacy and parenting quality remain unclear.

Attachment theory (Ainsworth & Wittig, 1969; Bowlby, 1969, 1980) may play a particularly salient role in guiding our understanding of how childhood maltreatment may come to affect an individual's later parental efficacy beliefs and behavior, especially considering the highly relational nature of parenting. Children who experience maltreatment may develop models of caregivers as detached, hostile, and untrustworthy and view themselves as unworthy or unlovable (Harter, 1998; Toth et al., 1997). Additionally, insecure attachment patterns among caregivers have been linked with an increased probability of insecure attachment patterns with one's own children (e.g., George & Solomon, 1996) and of the transmission of child abuse to the next generation (Zuravin, McMillen, DePanfilis, & Risley-Curtiss, 1996).

Individuals with histories of childhood maltreatment also have the potential to be highly self-critical. From a social-learning perspective, the experience of repeated insults (both physical and emotional) may cause children to adopt a similarly critical view of themselves through modeling the behavior of those who abused them (Glassman, Weierich, Hooley, Deliberto, & Nock, 2007) and perhaps internalizing such abusive attitudes. Indeed, maltreated children show significant deficits in their self-system processes even from a young age (Cicchetti, 1991; Toth, Cicchetti, MacFie, Maughan, & Vanmeenan, 2000). Attachment theory-driven research suggests that the psychological unavailability, inconsistent accessibility, and chronic insensitivity characteristic of the depressed and/or maltreating parent lead the child to construct a working model of attachment figures as unavailable, and consequently of the self as unworthy of love (Cicchetti, 1991; Cummings & Cicchetti, 1990; Radke-Yarrow, 1991). Research consistently shows that maltreated children have less positive self-concepts than non-maltreated children (Bolger, Patterson, & Kupersmidt, 1998; Cicchetti, Toth, & Lynch, 1995; Toth, Manly, & Cicchetti, 1992; Toth et al., 2000). These deleterious effects of maltreatment on self-system processes are expected to contribute to low global self-esteem due to feelings of inadequacy and incompetence (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1994; Kim & Cicchetti, 2006). Maltreated children also may express overbright positive affect, which some have attributed to a false sense of self (e.g., Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1994; Koenig, Cicchetti, & Rogosch, 2000). In fact, one study posits that the inflated self-efficacy exhibited by emotionally maltreated children may be a result of their engagement in defensive processing and suppressed negative affect (Kim & Cicchetti, 2003). Such maladaptive self-concepts and self-critical judgments may then translate into low parental efficacy as these children and adolescents become parents. Attachment theorists suggest this transition to be particularly challenging for previously maltreated parents as the new parent-child relationship may activate their working model of attachment figures as unavailable and of the self as unworthy or unlovable.

The association between depression and childhood maltreatment is firmly established in the literature, whereby maltreated individuals are more likely to develop depressive symptomatology both in childhood (e.g., Cicchetti & Toth, 1995; Toth, Manly, & Cicchetti, 1992; Widom, DuMont, & Czaja, 2007) and into their adult years (e.g., Bemporad & Romano, 1992). Research also suggests that parental depressive symptoms are often associated with mothers' lack of perceived parenting competency, at-risk parenting attitudes, and unrealistic expectations of child behavior (Dumas & Serketich, 1994; Forehand, McCombs, & Brody, 1987). As such, the role of maternal depression in the links between child maltreatment, adult self-criticism and maternal self-efficacy must be addressed. Numerous studies have found higher levels of depressive symptoms to be related to lower parental self-efficacy (Gross, Conrad, Fogg, & Wothke, 1994; Teti & Gelfand, 1991). While the parenting of depressed mothers has been characterized as helpless, critical, hostile, disorganized and less active than that of non-depressed mothers (Gelfand & Teti, 1990; Goodman, 1992), Teti and Gelfand (1991) found that maternal depression related to maternal competence only through its effect on maternal efficacy beliefs. Although the link between childhood maltreatment and self-criticism is firmly established in the literature (see Kopala-Sibley & Zuroff, 2014 for review), the question remains as to whether the experience of childhood maltreatment exerts its impact on later maternal efficacy beliefs through these degraded self-system processes over and above the influence of mothers' depressive status.

The aims of the current study were to characterize the self-critical attitudes of a sample of depressed and non-depressed low-income mothers, many of whom reported histories of childhood maltreatment. Consistent with the extant literature, we hypothesized that mothers with histories of childhood maltreatment would show higher levels of self-criticism. We also examined the maternal efficacy levels of mothers with and without histories of various forms of childhood maltreatment, in order to extend the literature on the maternal efficacy of individuals having experienced CSA to populations with other subtypes of maltreatment. We expected that mothers with more extensive experiences of childhood maltreatment would evidence lower levels of self-perceived efficacy in their role as parent. Finally, to address the question of what mechanisms may lead adults maltreated as children to exhibit low levels of maternal efficacy, we assessed whether self-criticism mediates the association between childhood maltreatment history and decreased maternal efficacy beliefs over a one year time period, and whether such a relation held among both depressed and non-depressed mothers.

Method

Participants and procedure

The data for this study were drawn from a larger randomized clinical trial evaluating the effectiveness of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) for depression among low-income mothers with a 12-month old infant (see Toth et al., 2013). A community sample of non-treatment seeking, biological mothers were recruited from primary care clinics serving low-income women and Women, Infant, and Children (WIC) clinics in Western New York. To be eligible, mothers needed to be within the age range of 18-44, have a 12-month old infant, and reside at or below the federal poverty level. Mothers were included in the depressed group if they scored 19 or higher on the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996), indicating moderate to severe depressive symptoms, and met MDD diagnostic criteria based on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (DIS-IV; Robins, Cottler, Bucholz, & Compton, 1995).

To eliminate any confounding intervention effect, only data on depressed mothers randomized to the enhanced control condition (n = 68) and non-depressed mothers (n = 59) were included in the current analyses. Women in the enhanced control condition were not required to be in treatment; however, they had been offered referral to services typically available in the community, as it is unethical to withhold treatment for those identified as depressed. At time 2, 38% (n = 35) of the mothers in the enhanced control condition reported having received some sort of mental health or counseling services. Mothers ranged in age from 18-38 (M = 25.03). Over half of the sample identified as Black (n = 79, 62.2%), 21.3% as White (n = 27), and the remaining 16.5% as Other (n = 21). In terms of ethnicity, 15% of participating mothers identified themselves as Hispanic (n = 19). Median annual income for families in this sample is approximately $17,000. The majority of the sample reported having never been married (n = 101, 79.5%), while 15% (n = 19) reported being currently married and 5.5% (n = 7) as being either separated or divorced.

Families were assessed at baseline when infants were 12-months old and again approximately one year later. Due to potential variability in literacy and reading ability, trained interviewers read all self-report measures aloud while participants followed along and marked their answers.

Measures

Depression

The Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (DIS-IV; Robins et al., 1995) is a structured interview to assess diagnostic criteria for Axis I disorders as categorized by the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). The interview assesses for symptoms present in the past year, the past 6 months, and those that are current or remitted. When comparing DSM diagnoses made by psychiatrists and those made by the DIS, Robins and colleagues (1981) reported mean κ of 0.69, sensitivity of 75%, and specificity of 94%. All interviewers were trained to criterion reliability in DIS administration, and computer-generated diagnoses for depression were used for the purposes of this study. Of the current sample, 53.5% (n = 68) mothers met criteria for a current major depressive episode while 46.5% (n = 59) were non-depressed. To capture the bimodal nature of this sample, a binary variable was created to reflect either the presence or absence of a current depressive diagnosis1.

Childhood trauma

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; Bernstein et al., 2003) consists of 25 self-report items that assess retrospective accounts of child maltreatment. Participants are asked to rate statements reflecting experiences occurring before the age of 18 on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from never true to very often true. Example statements include items such as “When I was growing up, people in my family hit me so hard that it left me with bruises or marks” or “When I was growing up, I didn't have enough to eat”. Domains assessed include emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect. Bernstein and Fink (1998) report moderately high internal consistency (α = 0.66-0.92) and good test-retest reliability (α = 0.79-0.86). Dichotomous variables reflecting either the presence or absence of each childhood maltreatment subtype from CTQ subscale scores were created based on pre-established cut-offs (Walker et al., 1999; Simon et al., 2009). Analyses in this study then utilized a variable representing the number of reported maltreatment subtypes that surpassed the given threshold. Studies show the CTQ demonstrates good convergent validity with other self-report and interview measures of child maltreatment (Bernstein et al., 2003; Hyman, Garcia, Kemp, Mazure, & Sinha, 2005). The CTQ demonstrated good reliability in this sample (α = .80).

In this sample, 65.4% of mothers were classified as having ‘any maltreatment’. Of these mothers, 68.7% met for having experienced emotional abuse before the age of 18, 50.6% for sexual abuse, 48.2% for physical abuse, 81.9% for emotional neglect, and 38.6% for physical neglect. These categories were not mutually exclusive as 27.7% of mothers met for one type of maltreatment while 15.7% met for two types, 14.5% for three types, 25.3% for four types, and 16.9% for five subtypes of maltreatment.

Self-Criticism

The Depressive Experiences Questionnaire (DEQ, Blatt et al., 1976) is a 66-item self-report questionnaire gauging respondents' feelings and attitudes about the self and interpersonal relations. The measure is based on Blatt's (2006) “two polarities” model, which understands personality development, organization, and psychopathology through the complex, dialectic relation between two psychological dimensions—relatedness and self-definition (Blatt & Luyten, 2009). Given the focus of this investigation, only the Self-Criticism subscale was used, which taps deviations from the self-definition dimension. The subscale consists of 17 self-report items such as, “I often don't live up to my own standards or ideals”, which subjects rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree. The Self-Criticism factor has shown adequate intratest homogeneity and test-retest reliability (Blatt et al., 1982).

Maternal Efficacy

The Maternal Efficacy Questionnaire (MEQ; Teti & Gelfand, 1991) is a 10-item questionnaire that assesses a mother's feelings of self-efficacy in relation to specific demands of the parenting role. The items are designed to tap the mother's sense of her ability to understand her child's wants and needs, get her child's attention, engage in positive interaction with her child, appreciate and respond to the child's preferences, and take care of the child's basic needs (e.g., “When your child is upset, fussy or crying, how good are you at soothing him or her?”). The MEQ was administered with mothers at both time 1, when parenting a 12 month old infant, and again at time 2, when mothers were then parenting a toddler with more demanding developmental needs. Internal consistency for the MEQ is 0.79-0.86 (Teti & Gelfand, 1991) and good construct validity has been demonstrated with the competence subscale of the Parenting Stress Inventory (0.75). The MEQ demonstrated good reliability in this study (α = .78).

Results

Table 1 provides the zero-order correlations among variables assessed in the current study. Marital status and the number of children currently living in the household were included as covariates as it was hypothesized that a mother's sense of efficacy as a parent would be increased with the support of a partner and decreased with more children in the household creating a more chaotic, stressful parenting environment. Maternal efficacy was measured at both waves in order to control for initial efficacy levels. This also allowed us to assess whether the effect of childhood maltreatment on self-criticism predicted a change in level of maternal efficacy from time 1, when the mothers were caring for 12 month old infants, to time 2, a year later when their children were toddlers. For ease of interpretation, a continuous variable depicting the number of positive symptoms endorsed on the DIS-IV was used for maternal depression instead of the binary diagnostic variable. Mothers who self-reported more extensive childhood maltreatment also indicated feeling less efficacious in their role as a mother (r=-.27) and were more likely to endorse higher levels of depressive symptoms (r=.48). Also, mothers having experienced more extensive maltreatment in childhood tended to hold more highly critical judgments of themselves (r=.50). Mothers with greater depressive symptoms tended to have lower perceived efficacy in their parental role at both time points (rT1=-.30; rT2=-.28). Finally, mothers who were more critical of themselves also reported feeling less efficacious as mothers both at time 1 (r=-.36) and time 2 (r=-.42).

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations among study variables.

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CTQ | 1.94 | 1.82 | -- | ||||||

| 2. DEQ-SC | -0.25 | 1.18 | 0.50** | -- | |||||

| 3. DIS-IV | 4.44 | 4.00 | 0.48** | 0.69** | -- | ||||

| 4. T1 MEQ | 3.46 | 0.31 | -0.17 | -0.36** | -0.30** | -- | |||

| 5. T2 MEQ | 3.44 | 0.34 | -0.27** | -0.42** | -0.28** | 0.41** | -- | ||

| 6. # Children | 2.30 | 1.41 | -0.02 | 0.18* | 0.17 | -0.26** | -0.25** | -- | |

| 7. Marital Status | 0.15 | 0.36 | -0.06 | -0.24** | -0.17 | 0.10 | 0.21* | 0.08 | -- |

Note.

= p <.05,

= p < .01.

CTQ = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; DEQ-SC = Depressive Experiences Questionnaire-Self-Criticism; DIS-IV = Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV MEQ = Maternal Efficacy Questionnaire. Marital Status was coded 0 = non-married, 1 = married.

Model Specification

We first tested whether self-criticism mediates the effect of mothers' history of childhood maltreatment on current maternal efficacy beliefs, and whether this relation was moderated by mothers' depression diagnostic status. A multiple-group path analysis within a Structural Equation Model (SEM) framework (e.g., Kline, 2005) was utilized. This multi-group SEM approach allows us to test whether the pathways in the given model vary based on the mothers' depressed or non-depressed group status. Both the fully constrained (χ2(14) = 18.76, ns; CFI= .92; RMSEA = .08; SRMR = .10) and unconstrained models (χ2(5) = 9.77, ns; CFI= .92; RMSEA = .13; SRMR = .05) were an adequate fit to the data. All main effect paths were tested for moderation in the unconstrained model. No significant difference between depressed and non-depressed groups was found (Δχ2(9) = 8.99, ns). This suggests that the effect of childhood maltreatment on maternal efficacy through self-critical beliefs does not vary based on depression diagnosis.

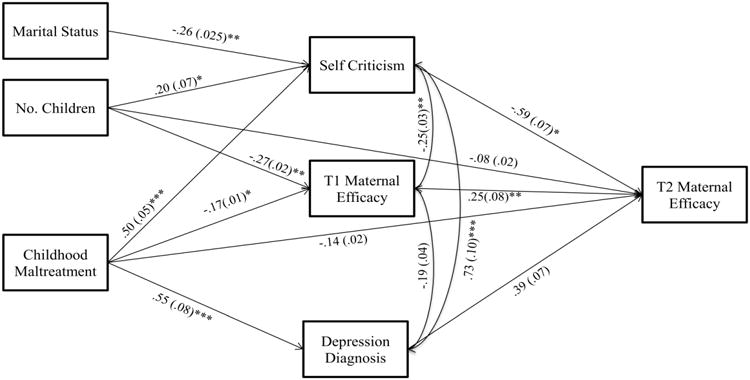

Although our preliminary multi-group model suggested that mother's depressive status did not moderate our proposed mediation model, we still needed to account for the fact that half of this sample was specifically recruited for depression in the enhanced control group and the other was non-depressed. Thus, the binary variable representing depressive status was included as a mediator using mothers' DIS-IV scores at time 1. This would allow us to examine the potential mediating role of self-criticism over and above the influence of current depression diagnosis on maternal efficacy. Number of children in the household and marital status were controlled for in relation only to variables with which they evidenced a significant correlation (see Table 1). These covariates, along with the childhood maltreatment variable were entered as correlated exogenous variables. All time 1 variables (self-criticism, time 1 maternal efficacy, and depressive status) were entered as mediators and residual covariances were modeled. Finally, all exogenous variables and mediators were modeled to predict time 2 maternal efficacy scores. This mediation model is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Mediation Model.

Standardized path coefficients for final structural equation model with standard error in parentheses.

Note: Although not depicted, all correlations among exogenous variables were modeled. Martial Status was coded 0 = non-married, 1 = married. T1 Depression Diagnosis was coded 0 = nondepressed, 1 = depressed. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

Analyses were performed using MPlus Version 7.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2011), using the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation method, which estimates means and intercepts to handle missing data. Since the depressive status variable was binary, the weighted least squares estimator with mean and variance adjustments (WLSMV) was used, which computed probit paramater estimates for the categorical outcomes (i.e., binary depression variable predicted from CTQ). Model fit was estimated with the robust WLSMV chi-square statistic, comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the weighted root-mean-square residual (WRMR). The following were considered to indicate good model fit: CFI values greater than .95, RMSEA values less than .06, WRMR values less than .90, and a non-significant chi-square statistic (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Yu and Muthén, 2002).

Mediational Model Analyses

Fit indices suggest the current model is an adequate fit to the data, χ2(4) = 9.64, p = 0.05, (CFI= .96, RMSEA = .11, WRMR = .60)2. Our findings demonstrate that mothers' self-reported experiences of childhood maltreatment were related to a greater likelihood of depression diagnosis at T1 (β = 0.73, p < .001). As anticipated, more extensive childhood maltreatment was related to greater self-criticism, β = 0.50, p < .001, while controlling for number of children. Moreover, higher self-criticism at time 1 significantly predicted lower maternal efficacy at time 2 (β = -0.59, p < .05). By controlling for maternal efficacy levels at time 1, these results indicate that there is a decrease in maternal efficacy from time 1 to time 2. Mediation was tested using 95% asymmetric confidence intervals via RMediation (Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011). There was a significant indirect effect of childhood maltreatment on time 2 maternal efficacy via self-criticism (95% CI: -0.11 — -0.01)3.

Discussion

The current study sought to characterize the self-critical attitudes of a sample of depressed and non-depressed low-income mothers with varying histories of childhood maltreatment. As has been previously established, mothers with more extensive experiences of maltreatment in childhood showed higher levels of self-criticism as adults. To extend previous research, we also examined maternal efficacy levels among mothers with and without histories of various forms of childhood maltreatment. As hypothesized, mothers who had experienced more extensive childhood maltreatment perceived themselves as less efficacious as a parent. This is a particularly important contribution to the literature as the majority of prior research has focused on victims of childhood sexual abuse. Finally, we examined whether the impact of childhood maltreatment on maternal efficacy beliefs was transmitted through self-criticism, over and above the influence of maternal depression. Results indicated that self-criticism mediated the relation between childhood maltreatment and maternal efficacy, above and beyond the influence of mothers' depressive diagnostic status. Specifically, mothers who experienced a greater number of maltreatment subtypes as children reported more self-critical judgments, which in turn led to decreased levels of perceived efficacy in their maternal role from time 1 to time 2. It is plausible that mothers' belief in their efficacy as a parent changes as they transition from parenting a 12-month-old infant to the tumultuous toddler years. These findings suggest that mothers' self-critical attitudes stemming from their history of childhood maltreatment lowers their perceived competency in meeting the increased parenting demands of their children's changing developmental needs. Previously maltreated mothers may be particularly sensitive to the challenge of managing their toddlers' newfound autonomy and independence if their own strivings for autonomy were not well received by their primary attachment figure in childhood.

This finding is particularly robust given that the mediating role of self-criticism remains significant when controlling for the presence of a current diagnosis of depression, suggesting that is it not the diagnosis of depression per se that affects previously maltreated mothers' beliefs in their efficacy as a parent, it is how self-critical they are. This indicates that the negative impact of self-criticism on maternal efficacy beliefs was not simply a marker of maternal depression. In fact, our preliminary multi-group model testing the potential moderation of our model by depression status was found to be non-significant, suggesting that even in non-depressed mothers self-criticism stemming from childhood maltreatment may still act as a vulnerability factor for decreased maternal efficacy beliefs. Moreover, as all mothers were low-income, this lack of significance between groups may also be an indication of the influence of poverty.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine a specific cognitive mechanism linking childhood maltreatment to later maternal efficacy beliefs in a high-risk, low-income sample. Related work by Caldwell and colleagues (2011) found that the damaging effects of childhood maltreatment on a parent's sense of competence and satisfaction were transmitted indirectly through symptoms of depression. The current study extends this work by further specifying self-criticism as a central contributor to the decreased maternal efficacy beliefs of both depressed and non-depressed mothers with histories of childhood maltreatment.

Identifying mechanisms linking childhood maltreatment and later maternal efficacy beliefs is critical to develop interventions aimed at breaking the intergenerational transmission of abuse. Various intervention studies lend support to the modifiable nature of parental self-efficacy and its importance in parenting practices. For example, Gross et al. (1995) found that improvements in parenting and child behavior were related to increases in maternal efficacy following intervention for promoting positive parent-child relationships in families with 2-year-olds. Our findings suggest that self-criticism may be a promising target for intervention with mothers who have histories of childhood maltreatment in order to bolster their beliefs in their efficacy as parents and strive to prevent the transmission of abuse. Enhancing the maternal efficacy beliefs of low-income mothers is especially important given the protective role strong maternal efficacy beliefs can play in reducing the psychological risk faced by children living in poverty (Elder, 1995). Our results suggest that mothers' self-criticism could be included among other cognitive mechanisms, such as aggressive response biases (Berlin, Appleyard, & Dodge, 2011) or hostile attributions (Berlin, Dodge, & Reznick, 2013), that mediate the link between mothers' maltreatment experience and subsequent child maltreatment and have also been identified as potential targets for intervention. The current findings also lend support to the potential benefit of targeting the self-representations of maltreated children in an effort to prevent later self-critical attitudes and low parental efficacy beliefs as these children grow to become parents themselves.

Despite its contributions to the literature, some methodological limitations should be noted. First is the use of retrospective reports of childhood maltreatment. While it is unclear whether self-reports reflect true histories, evidence suggests that retrospective reports of childhood maltreatment generally provide valid and reliable estimates of significant past events (Bernstein et al., 1994). Another potential limitation is dependence on self-report in the measurement of maternal efficacy and self-criticism. The common method may inflate the strength of the relation between these constructs. Similarly, although the longitudinal assessment of maternal efficacy allowed us to establish the temporal ordering of variables, the relationship between self-criticism and maternal efficacy beliefs are most likely reciprocal. Questions of directionality may be better addressed using multiwave data to examine whether childhood maltreatment predicts changes in self-criticism that precede changes in maternal efficacy (Cole & Maxwell, 2003; Maxwell & Cole, 2007).

The findings of this study highlight several future directions for research. The parenting quality of individuals who were previously maltreated as children has long been a focus of investigation (Cort et al., 2011; Belsky, Conger, & Capaldi, 2009; DiLillo & Damashek, 2003; Cicchetti & Rizley, 1981; Egeland, Jacobvitz, & Sroufe, 1988). Given the strong evidence base suggesting that a parent's sense of self-efficacy is closely intertwined with parenting quality (Coleman & Karraker, 1998), maternal efficacy seems to be an important compliment to general, more skill-based parenting interventions within this population. It is important to note that not all parents with histories of childhood maltreatment go on to show low levels of parental efficacy beliefs, and certainly not all go on to maltreat their own children (for review see Berlin, Appleyard, & Dodge; 2011). It is possible that maternal efficacy beliefs, if positive, may help explain the lack of intergenerational transmission. However, for those mothers who do manifest low maternal efficacy beliefs, continuing to identify factors associated with the development of these beliefs, such as self-criticism, is critical to facilitate the targeting of interventions toward parents in high-risk populations, including those with histories of maltreatment and those living in economically disadvantaged conditions.

As the current findings suggest, mothers' self-critical judgments may serve as a crucial inroad to enhancing maternal efficacy beliefs within this population. This study stresses the importance of including self-systems processes in the clinical intervention of maltreated individuals both in childhood and as they become parents. Future intervention studies should consider assessing how changes in mothers' self-criticism and other aspects of cognitive style (e.g., aggressive biases, negative attributions) impact efficacy beliefs as well as actual parenting behaviors assessed with observational methods. The inclusion of both self-report and observational measures of parenting behavior is an important next step in more directly assessing factors that influence the development of parenting behaviors among previously maltreated mothers. With this knowledge, we may be better equipped to break the cycle of abuse that unfortunately is all too often passed down through generations.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge and greatly appreciate the funding support of this research by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH67792) and the Spunk Fund, Inc.

Footnotes

One mother met criteria only for uncomplicated bereavement, so this case was subsequently omitted from analyses.

Less weight was given to the RMSEA fit index due to the smaller sample size. It has been shown that the RMSEA index may behave in unintended ways when sample size is small (Rigdon, 1996).

Mediation holds when using continuous childhood maltreatment variable, yet reduces model fit.

References

- Ainsworth M, Wittig B. Attachment and exploratory behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. In: Foss BM, editor. Determinants of infant behavior. Vol. 4. London: Methuen; 1969. pp. 113–136. [Google Scholar]

- Ardelt M, Eccles JS. Effects of mothers' parental efficacy beliefs and promotive parenting strategies on inner-city youth. Journal of Family Issues. 2001;22(8):944–972. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy in changing societies. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the BDI-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Conger R, Capaldi DM. The intergenerational transmission of parenting: introduction to the special section. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45(5):1201–1204. doi: 10.1037/a0016245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Jaffee SR, Sligo J, Woodward L, Silva PA. Intergenerational transmission of warm‐sensitive‐stimulating parenting: A prospective study of mothers and fathers of 3‐year‐olds. Child Development. 2005;76(2):384–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bemporad JR, Romano SJ. Childhood maltreatment and adult depression: A review of research. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Developmental Perspectives on Depression Rochester symposium on developmental psychopathology. Vol. 4. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 1992. pp. 351–375. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Appleyard K, Dodge KA. Intergenerational continuity in child maltreatment: Mediating mechanisms and implications for prevention. Child Development. 2011;82(1):162–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01547.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Dodge KA, Reznick JS. Examining pregnant women's hostile attributions about infants as a predictor of offspring maltreatment. JAMA pediatrics. 2013;167(6):549–553. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: A retrospective self-report. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M, Wenzel K, Sapareto E, Ruggiero J. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151:1535–1537. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, et al. Desmond D. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27(2):169–190. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt SJ. A fundamental polarity in psychoanalysis: Implications for personality development, psychopathology, and the therapeutic process. Psychoanalytic Inquiry. 2006;26:492–518. [Google Scholar]

- Blatt SJ, D'Afflitti JP, Quinlan DM. Experiences of depression in normal young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1976;85(4):383–389. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.85.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt SJ, Luyten P. A structural-developmental psychodynamic approach to psychopathology: Two polarities of experience across the life span. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:793–814. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatt SJ, Quinlan DM, Chevron ES, McDonald C, Zuroff D. Dependency and self-criticism: Psychological dimensions of depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1982;50(1):113–124. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger KE, Patterson CJ, Kupersmidt JB. Peer relationships and self‐esteem among children who have been maltreated. Child Development. 1998;69(4):1171–1197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby JB. Attachment and Loss Vol 1: Attachment. New York: Basic Books; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby JB. Attachment and loss Vol 3: Loss, sadness and depression. New York: Basic Books; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bugental DB, Blue J, Lewis J. Caregiver beliefs and dysphoric affect directed to difficult children. Developmental Psychology. 1990;26(4):631–638. [Google Scholar]

- Bugental DB, Cortez VL. Physiological reactivity to responsive and unresponsive children as moderated by perceived control. Child Development. 1988;59(3):686–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugental DB, Shennum WA. “Difficult” children as elicitors and targets of adult communication patterns: An attributional-behavioral transactional analysis. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1984;49(1):1–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JG, Shaver PR, Li CS, Minzenberg MJ. Childhood maltreatment, adult attachment, and depression as predictors of parental self-efficacy in at-risk mothers. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2011;20(6):595–616. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D. Fractures in the crystal: Developmental psychopathology and the emergence of self. Developmental Review. 1991;11(3):271–287. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rizley R. Developmental perspectives on the etiology, intergenerational transmission, and sequelae of child maltreatment. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 1981;1981(11):31–55. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. The toll of child maltreatment on the developing child: Insights from developmental psychopathology. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1994;3(4):759–776. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. A Developmental Psychopathology Perspective on Child Abuse and Neglect. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1995;34(5):541–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199505000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. Child Maltreatment. In: Lamb M, editor. Handbook of child psychology and developmental science. 7th. Vol. 3. New York: Wiley; 2015. pp. 513–563. Socioemotional process. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL, Lynch M. Bowlby's dream comes full circle. In: Ollendick TH, Prinz RJ, editors. Advances in Clinical Child Psychology. Springer US; 1995. pp. 1–75. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen T. Motherhood among incest survivors. Child Abuse &Neglect. 1995;19(12):1423–1429. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(96)80760-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112(4):558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole PM, Woolger C, Power TG, Smith KD. Parenting difficulties among adult survivors of father-daughter incest. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1992;16(2):239–249. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(92)90031-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman PK, Karraker KH. Self-efficacy and parenting quality: Findings and future applications. Developmental Review. 1998;18(1):47–85. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman PK, Karraker KH. Maternal self‐efficacy beliefs, competence in parenting, and toddlers' behavior and developmental status. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2003;24(2):126–148. [Google Scholar]

- Cort NA, Toth SL, Cerulli C, Rogosch F. Maternal intergenerational transmission of childhood multitype maltreatment. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2011;20(1):20–39. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Cicchetti D. Attachment, depression, and the transmission of depression. In: Greenberg MT, Cicchetti D, Cummings EM, editors. Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1990. pp. 339–374. [Google Scholar]

- DiLillo D, Damashek A. Parenting characteristics of women reporting a history of childhood sexual abuse. Child Maltreatment. 2003;8(4):319–333. doi: 10.1177/1077559503257104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas AR. Reported anxieties concerning intimate parenting in women sexually abused as children. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2000;24(3):425–434. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00154-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas JE, Serketich WJ. Maternal depressive symptomatology and child maladjustment: A comparison of three process models. Behavior Therapy. 1994;25(2):161–181. [Google Scholar]

- Egeland B, Sroufe A. Developmental sequelae of maltreatment in infancy. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 1981;1981(11):77–92. [Google Scholar]

- Egeland B, Jacobvitz D, Sroufe LA. Breaking the cycle of abuse. Child Development. 1988;59(4):1080–1088. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb03260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH. Life trajectories in changing societies. In: Bandura A, editor. Self-Efficacy in changing societies. New York: Cambridge Univ. Press; 1995. pp. 46–68. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH, Jr, Eccles JS, Ardelt M, Lord S. Inner-city parents under economic pressure: Perspectives on the strategies of parenting. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57(3):771–784. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson MF, Egeland B. A developmental view of the psychological consequences of maltreatment. School Psychology Review. 1987;16(2):156–168. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald MM, Shipman KL, Jackson JL, McMahon RJ, Hanley HM. Perceptions of parenting versus parent-child interactions among incest survivors. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29(6):661–681. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forehand R, McCombs A, Brody GH. The relationship between parental depressive mood states and child functioning. Advances in Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1987;9(1):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Friesen MD, Woodward LJ, Horwood LJ, Fergusson DM. Quality of parent–child relations in adolescence and later adult parenting outcomes. Social Development. 2013;22(3):539–554. [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand DM, Teti DM. The effects of maternal depression on children. Clinical Psychology Review. 1990;10(3):329–353. [Google Scholar]

- George C, Solomon J. Representational models of relationships: Links between caregiving and attachment. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1996;17(3):198–216. [Google Scholar]

- Glassman LH, Weierich MR, Hooley JM, Deliberto TL, Nock MK. Child maltreatment, non-suicidal self-injury, and the mediating role of self-criticism. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45(10):2483–2490. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH. Understanding the effects of depressed mothers on their children. Prog Exp Pers Psychopathol Res. 1992;15:47–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross D, Conrad B, Fogg L, Wothke W. A longitudinal model of maternal self‐efficacy, depression, and difficult temperament during toddlerhood. Research in Nursing & Health. 1994;17(3):207–215. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770170308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross D, Fogg L, Tucker S. The efficacy of parent training for promoting positive parent-toddler relationships. Research in Nursing & Health. 1995;18(6):489–499. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern R. Poverty and infant development. In: Zeanah CH, editor. Handbook of infant mental health. New York: Guilford; 1993. pp. 73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The effects of child abuse on the self-system. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 1998;2(1):147–169. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman SM, Garcia M, Kemp K, Mazure CM, Sinha R. A gender specific psychometric analysis of the early trauma inventory short form in cocaine dependent adults. Addictive behaviors. 2005;30(4):847–852. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izzo C, Weiss L, Shanahan T, Rodriguez-Brown F. Parental self-efficacy and social support as predictors of parenting practices and children's socioemotional adjustment in Mexican immigrant families. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community. 2000;20(1-2):197–213. [Google Scholar]

- Jones TL, Prinz RJ. Potential roles of parental self-efficacy in parent and child adjustment: A review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25(3):341–363. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Cicchetti D. Social self-efficacy and behavior problems in maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32(1):106–117. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3201_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Cicchetti D. Longitudinal trajectories of self‐system processes and depressive symptoms among maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Child Development. 2006;77(3):624–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00894.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practices of structural equation modeling. 2nd. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig AL, Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. Child compliance/noncompliance and maternal contributors to internalization in maltreating and nonmaltreating dyads. Child development. 2000;71(4):1018–1032. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopala-Sibley DC, Zuroff DC. The developmental origins of personality factors from the self-definitional and relatedness domains: A review of theory and research. Review of General Psychology. 2014;18(3):137. [Google Scholar]

- MacPhee D, Fritz J, Miller‐Heyl J. Ethnic variations in personal social networks and parenting. Child Development. 1996;67(6):3278–3295. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell SE, Cole DA. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychological Methods. 2007;12(1):23–44. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrazek P. Maltreatment and infant development. In: Zeanah CH, editor. Handbook of Infant Mental Health. New York: Guilford; 1993. pp. 159–170. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. Sixth. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998-2011. [Google Scholar]

- Neppl TK, Conger RD, Scaramella LV, Ontai LL. Intergenerational continuity in parenting behavior: Mediating pathways and child effects. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45(5):1241–1256. doi: 10.1037/a0014850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radke-Yarrow M. Attachment patterns in children of depressed mothers. In: Parkes CM, Stevenson-Kinde J, Marris P, editors. Attachment Across the Life Cycle. London: Routledge; 1991. pp. 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Rigdon EE. CFI versus RMSEA: A comparison of two fit indexes for structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1996;3(4):369–379. [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Cottler L, Bucholz K, Compton W. Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-IV. St. Louis, MO: Washington University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS. National Institute of Mental Health diagnostic interview schedule: Its history, characteristics, and validity. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1981;38(4):381–389. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290015001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon NM, Herlands NN, Marks EH, Mancini C, Letamendi A, Li Z, Pollack MH, Can Ameringen M, Stein MB. Childhood maltreatment linked to greater symptom severity and poorer quality of life and function in social anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26(11):1027–1032. doi: 10.1002/da.20604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teti DM, Gelfand DM. Behavioral competence among mothers of infants in the first year: The mediational role of maternal self‐efficacy. Child Development. 1991;62(5):918–929. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi D, MacKinnon DP. RMediation: An R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behavior Research Methods. 2011;43(3):692–700. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth SL, Cicchetti D, Macfie J, Emde RN. Representations of self and other in the narratives of neglected, physically abused, and sexually abused preschoolers. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9(04):781–796. doi: 10.1017/s0954579497001430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth SL, Cicchetti D, MacFie J, Maughan A, Vanmeenen K. Narrative representations of caregivers and self in maltreated pre-schoolers. Attachment & Human Development. 2000;2(3):271–305. doi: 10.1080/14616730010000849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth SL, Manly JT, Cicchetti D. Child maltreatment and vulnerability to depression. Development and Psychopathology. 1992;4(01):97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Toth SL, Rogosch FA, Oshri A, Gravener-Davis J, Sturm R, Morgan-López AA. The efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for depression among economically disadvantaged mothers. Development and Psychopathology. 2013;25(4pt1):1065–1078. doi: 10.1017/S0954579413000370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker EA, Gelfand A, Katon WJ, Koss MP, Von Korff M, Bernstein D, Russo J. Adult health status of women with histories of childhood abuse and neglect. The American Journal of Medicine. 1999;107(4):332–339. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00235-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Czaja SJ, DuMont KA. Intergenerational transmission of child abuse and neglect: Real or detection bias? Science. 2015;347(6229):1480–1485. doi: 10.1126/science.1259917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, DuMont K, Czaja SJ. A prospective investigation of major depressive disorder and comorbidity in abused and neglected children grown up. Archives of general psychiatry. 2007;64(1):49–56. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu CY, Muthen B. Evaluation of model fit indices for latent variable models with categorical and continuous outcomes. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association; New Orleans, LA. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zuravin S, McMillen C, DePanfilis D, Risley-Curtiss C. The intergenerational cycle of child maltreatment continuity vs discontinuity. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1996;11(3):315–334. [Google Scholar]