Abstract

Objective

To examine a wide range of study designs and outcomes to estimate the extent to which interventions in outpatient perinatal care settings are associated with an increase in the uptake of depression care.

Data Sources

PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, ClinicalTrials.gov, and Scopus (EMBASE) were searched for studies published between 1999 and 2014 that evaluated mental health care use after screening for depression in perinatal care settings.

Methods of Study Selection

Inclusion criteria were: 1) English language; 2) pregnant and postpartum women who screened positive for depression; 3) exposure (validated depression screening in outpatient perinatal care setting); and, 4) outcome (mental health care use). Searches yielded 392 articles, 42 met criteria for full text review, and 17 met inclusion criteria. Study quality was assessed using a modified Downs and Black scale.

Tabulation, Integration, and Results

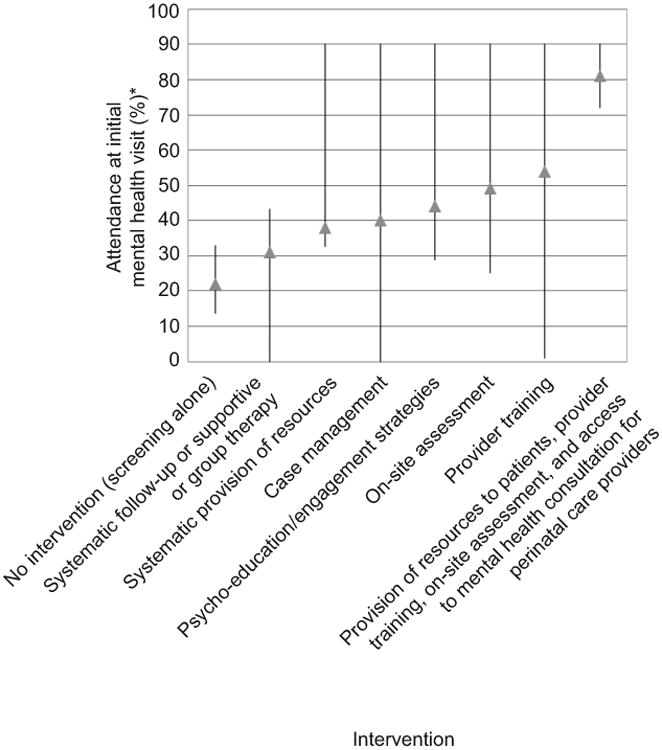

Articles were independently reviewed by two abstractors and consensus reached. Study design, intervention components and mental health care use were defined and categorized. Seventeen articles representing a range of study designs, including one randomized controlled trial (RCT) and one cluster RCT, were included. The average quality rating was 61% (31.0-90.0%). When no intervention was in place, an average of 22% (13.8-33.0%) of women who screened positive for depression had at least one mental health visit. The average rate of mental health care use was associated with a doubling of this rate with patient engagement strategies (44%, 29.0-90.0%), on-site assessments (49%, 25.2-90.0%), and perinatal care provider training (54%, 1.0-90.0%). High rates of mental health care use (81%, 72.0-90.0%) was associated with implementation of additional interventions, including resource provision to women, perinatal care provider training, on-site assessment, and access to mental health consultation for perinatal care providers.

Conclusion

Screening alone was associated with 22% mental health care use among women who screened positive for depression; however, implementation of additional interventions was associated with a 2-4 fold increased use of mental health care. While definitive studies are still needed, screening done in conjunction with interventions that target patient, provider and practice-level barriers are associated with increased improved rates of depression detection, assessment, referral, and treatment in perinatal care settings.

Introduction

Perinatal depression occurs in up to 18% of women1 and has deleterious effects on pregnancy, birth and child outcomes. There is a growing sense of urgency to develop approaches to identify and treat this serious illness because it remains under-diagnosed and under-treated.2,3 The perinatal period is viewed as a time that may be ideal to screen for, assess, and treat depression because women have frequent and regular contact with perinatal health care professionals.2 Recognizing this opportunity, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recently changed their recommendation from insufficient evidence to support universal screening4 to recommending that clinicians use a standardized tool to screen at least once during the perinatal period.5

There is a wide range of legislation enacted around perinatal depression screening6 and numerous recommendations to screen for perinatal depression.4,5,7-10 However, this remains controversial because systematic reviews to date report limited utility for universal screening. Prior reviews are limited because they do not include non-randomized study designs11,12-14 and thus do not consider the full range of available evidence. When definitive studies are lacking, it is important to invoke varying levels of evidence to shed light on the controversy and inform policy.15

In this review, we evaluate a range of study designs to understand what types of interventions need to be in place to enhance uptake of mental health care for perinatal depression. We aim to answer a practical question: To what extent are intervention type and intensity associated with differential engagement in mental health care for pregnant and postpartum women with depression?

Sources

This review was completed using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The Population Intervention Comparison Outcome (PICO) method was used to develop our study question.16 Search strategies were developed by a health sciences librarian (L.L.). The librarian translated the search strategies based upon each database's respective controlled vocabulary (MeSH, CINAHL Subject Headings, the Thesaurus of Psychological Index Terms and EMTREE) and command language, using additional free text terms when appropriate. Major concepts searched were Pregnancy, Prenatal Care, Postnatal Care, Postpartum Depression, Screening, Therapy, Mental Health Referral and Consultation, Delivery of Integrated Health Care and Mental Health Services Accessibility (Appendix 1, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx). PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, ClinicalTrials.gov, and Scopus (EMBASE) were searched using a January 1, 1999, through June 30, 2014, date limit to identify studies matching the search parameters. The initial search in PubMed was executed using the following search terms: (Pregnancy[Mesh] OR Perinatal Care[Mesh] OR Prenatal Care[Mesh]) OR (Postpartum Period[Mesh] OR Mothers[Mesh] OR Perinatal[Mesh] OR Antepartum[Mesh]) AND (Depression, Postpartum[Mesh] OR Depression[Mesh] OR Depression[ti]) AND (Mass Screening[Mesh] OR screen*[ti] OR identify*[ti] OR treatment[ti] OR intervention[ti] OR detect*[ti] OR study[ti] OR therapy*[ti]) AND (Referral and Consultation[Mesh] OR Delivery of Health Care, Integrated[Mesh] OR Health Services Accessibility[Mesh] OR Women's Health[Mesh] OR Women's Health Services[Mesh] OR Mental Health Services[Mesh] OR access[ti] OR care[ti] OR clinic[ti] OR setting[ti] OR site[ti] OR program[ti] OR collaborate*[ti] OR step*[ti] OR location*[ti] OR service[ti]) AND (“2003/01/01”[PDAT] : “2013/09/30”[PDAT]). These terms were utilized in the other sources as well with modifications based on differing controlled vocabularies inherent in each source if applicable (Appendix 1, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx). The date limit was chosen based on the time when screening for perinatal depression developed momentum as a public health issue. The included studies all obtained informed consent from study participants. The University of Massachusetts Medical School Institutional Review Board determined that this study did not require their review or oversight because analyses included only published de-identified data.

Study Selection

Two of the authors (N.B. and L.L.) reviewed each citation and abstract using a standardized data abstraction form created by author N.B. Inclusion criteria consisted of: 1) language limited to English; 2) exposure to depression screening with any validated tool in an outpatient perinatal care setting resulting in study participants that were pregnant or postpartum (within one year of delivery) adult women who screened positive for depression; and, 3) documented participation in at least one mental health care assessment with a perinatal or mental health care provider. Exclusion criteria consisted of: 1) non-English language; 2) review article, case report, letter or commentary; and, 3) no peer review.

The abstracts yielded from the initial literature search were reviewed independently by two abstractors (N.B. and L.L.). Full text articles were retrieved as needed to determine eligibility criteria. After discussion, consensus was reached among the abstractors in 100% of cases. The full text of the articles that met inclusion criteria were obtained and bibliographic references were hand searched to identify any additional articles. Our research strategy also included querying recognized experts in the fields to identify additional studies.

To assess the methodological quality of both randomized and non-randomized studies, the quality of each study was assessed using a modified Downs and Black criterion.17 The Downs and Black scale examines validity, bias, power, and other study attributes. As described and recommended in prior methodological systematic reviews,18 we modified the original Downs and Black scale17 and excluded items that were not applicable to the designs of eligible studies. The original scale has a maximum score of 32 and includes 27 items. Items not relevant to study designs being assessed were removed. For example, items specific to randomized trials were removed for observational studies. For each study, a percentage quality score was calculated by dividing the total score received by the maximum score possible. The checklist item about power was dichotomized into sufficient or insufficient power. Sufficient power was defined as 0.80 and a criterion α of 0.05. Because of the clinical heterogeneity and differences in measurement outcomes in the included studies, meta-analyses were not performed.

Due to the dearth of RCTs on this topic, quasi-experimental and observational study designs were included in order to assess the range of evidence currently available. Studies that randomly allocated women to receive an intervention or no intervention were categorized as RCTs. Studies that allocated groups, clinic or practice sites to receive an intervention or no intervention were categorized as cluster RCTs. Studies that collected data on level of performance before the intervention took place (pre-) and examined the difference in the pre-test and post-test results were considered quasi-experimental studies. Studies that followed women and evaluated treatment rates among women who may or may not have been exposed to an intervention were considered observational studies.

Key variables and outcomes were categorized according to pre-specified operational definitions as shown in Table I.

Table I. Characteristics of the 17 Studies Included in the Systematic Review of Screening and Referral for Perinatal Depression.

| Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| Intervention Component | |

| Referral to mental health treatment/evaluation | Provided referral for mental health treatment/evaluation individual patients. |

| On-site assessment | Mental health care assessment by an on-site case manager, social worker, or perinatal care provider (e.g. obstetrician or midwife) in the perinatal care setting. |

| Access to mental health consultation for perinatal care providers | Perinatal care providers were encouraged to utilize and are given access to expert mental health consultation online or by telephone to guide treatment provision to individual patients after completion of required training. |

| Perinatal care provider training | Systematic approach to training perinatal care providers in the assessment and treatment of depression and other mental health concerns. |

| Case management | Involvement of a perinatal care manager from the obstetric clinic site who conducts an initial mental health assessment or refers patients for mental health assessment/treatment. |

| Systematic provision of resources to patients | Perinatal care team or research team provides mental health resources or referrals to depressed women. |

| Systematic follow-up with provision of resources/referral to patients | Consistent in-person or telephonic follow-up with depressed women in order to help them access mental health care. |

| Supportive psychotherapy/referral to support group | Offering depressed women psychotherapy that incorporates principles of interpersonal and cognitive behavioral therapy (supportive psychotherapy) for an undefined number of sessions or inviting depressed women to participate in a group facilitated by case managers (support group). |

| Provider feedback loop | Provided feedback to providers on their screening and/or treatment rates. |

| Psycho-education/treatment engagement strategies | The perinatal care or research team discusses screening results or resources for treatment, provides educational material about perinatal depression, or use of tools to facilitate depression discussion in the perinatal care setting. This includes strategies with varying levels of intensity that range from provision of educational material to feedback interventions that involve non-directive counseling strategies for individual patients based on cognitive behavioral therapy. |

| CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy) | Offering CBT provided by mental health professionals in a non-perinatal care setting. |

| Mental Health Utilization Outcomes | |

| Positive screen and referred for treatment | Screened positive and offered mental health assessment with perinatal care provider and / or referral information or appointment with a mental health provider. |

| Accepted referral for mental health care | Referred for mental health care assessment and accepted referral. |

| Participated in mental health assessment | Participated in a mental health care assessment with a perinatal or mental health care provider. |

| Attended follow-up mental health care | Participated in more than one mental health appointment with a mental health care provider or participated in more than one perinatal care provider appointment that involved mental health care. |

Results

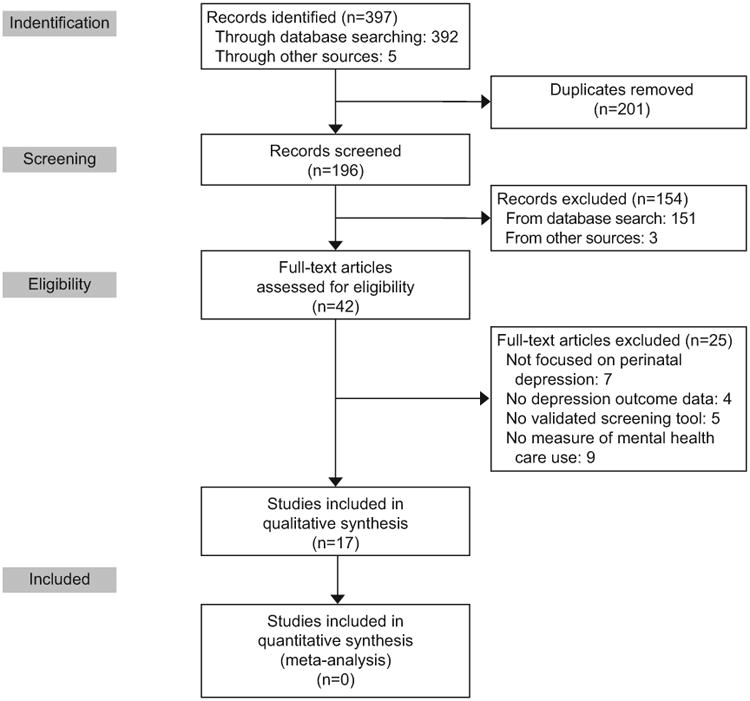

The literature search yielded 392 articles (Figure I). After eliminating duplicates, a total of 196 references were identified. Of the 196 reviewed, 154 were removed after abstract review because they did not meet inclusion criteria, leaving 42 articles for full-text review. Of the 42 full-text articles reviewed, 25 were removed because they did not meet inclusion criteria. Therefore, we report on 17 studies that are summarized in Table I.

Figure 1.

Article selection process.

Quality rating, based on the modified Downs and Black criteria, ranged from 31% to 90% (of a possible 100%); the average score was 61%. In general, quality ratings were lowered because studies did not: 1) report the random variability in the data for the main outcomes; 2) describe the characteristics of patients lost to follow-up; 3) describe principal confounders; 4) demonstrate reliable compliance with the intervention; 5) report actual probability values for the main outcomes; and, 6) make it clear whether any results were based on retrospective unplanned analyses.

Sample sizes ranged from 293 - 17,648 participants (Table II). Most studies did not include a comparison group (n=12).2,3,19-32 Three studies compared participants' treatment use or depression severity with a pre-intervention group comprised of different patients than those who participated in the intervention.19,20,24 Two studies made a formal comparison with a usual care control group.3,33

Table II. Characteristics of the 17 Studies Included in the Systematic Review of Screening and Referral for Perinatal Depression.

| Author, Year | Study Type, Setting and Country | Sample Size and Comparison Groups | Screening tool and time points | Intervention | Quality Score (%) ‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yawn et al, 201233 | Cluster RCT 28 family medicine practices in USA |

n=2,343 PP Intervention: n=399 Usual care: n=255 |

EPDS PHQ-9 PP Follow-up at 6 and 12 month PP |

Intervention sites if EPDS > 10: provider training, on site assessment, engagement strategies, referral Usual Care: 1 hour provider training |

19/21 (90%) |

| Carter et al, 20053 | RCT Perinatal care setting in New Zealand |

n=370 No comparison group |

EPDS 12-22 weeks GA EPDS and SCID at initial, end and PP assessment |

EPDS > 12: CBT | 7/17 (41%) |

| Smith et al, 20092 | Cohort >1 publicly funded obstetric clinics in USA |

n=465 No comparison group |

PRIME-MD BHQ during pregnancy/ PP, EPDS 1,3,6 mos after initial assessment, PHQ-9 | Referral, on site assessment, resources | 16/20 (80%) |

| Smith et al, 20092 | Cohort >1 publicly funded obstetric clinics in USA |

n=465 No comparison group |

PRIME-MD BHQ during pregnancy / PP, EPDS 1,3, 6 mos after initial assessment, PHQ-9 | Referral, on site assessment, resources | 16/20 (80%) |

| Smith et al, 200430 | Cohort 2 public-sector obstetric clinics in USA |

n=387 No comparison group |

PRIME-MD BHQ n=80 1st trimester, n=144 2nd trimester, n=163 3rd trimester |

None | 16/20 (80%) |

| Goodman et al, 201022 | Cohort 2 hospital-affiliated Obstetric clinics in USA |

n=525 enrolled n=491 (93.5%) prenatal sample n=299 (61%) PP EPDS No comparison group |

EPDS, PHQ-9, anxiety questions during 3rd trimester & 6 weeks PP | None | 13/17 (77%) |

| Reay et al, 201123 | Cohort Perinatal care setting in 2 public and 2 private hospitals in Australia |

Antenatal: n=984 PP: n=714 No comparison group |

EPDS BDI Antenatal 6-8 weeks PP 2 year follow-up |

EPDS ≥13: engagement strategies, resources | 12/16 (75%) |

| Chen et al, 201121 | Cohort 2 obstetric clinics in Singapore |

n=2148 No comparison group |

EPDS 2-6 wks PP, follow-up assessment 6 months later or discharge |

EPDS 10-12: case management, on site assessment EPDS ≥13: case management, on site assessment, engagement strategies, referral, resources, supportive counseling/group |

12/18 (67%) |

| Yonkers et al, 200924 | Cohort >1 publicly funded obstetric clinic in USA |

n=1,336 n=400 enrolled in program n=367 pre-program n=569 not enrolled No comparison group |

PRIME-MD BHQ depression module Enrollment in program during pregnancy or within 6 months PP |

Provider training, case management, resources, referral, follow-up of resources/referral | 13/22 (59%) |

| Flynn et al, 200631 | Cohort 1 university hospital obstetrics clinic in USA | n=1298 No comparison group | EPDS (time 1-4) BDI-II (time 1, 3,4) SCID mood disorder module for DSM-IV (time 1 | EPDS ≥10: engagement strategies, referral, resources, on site assessment | 9/16 (56%) |

| Burton et al, 201125 | Observational Community-based medical center in USA |

n=293 No comparison group |

EPDS 36 wks GA In hospital after delivery 6 wks PP |

EPDS ≥10: referral to mental health treatment / evaluation, supportive counseling | 12/17 (71%) |

| Nelson et al, 201332 | Prospective, population-based observational study Obstetric clinics in USA | n=17,648 No comparison group |

EPDS 2-6 weeks PP |

Referral | 11/16 (69%) |

| Marcus et al, 200327 | Observational 10 obstetric clinics in USA | n=3,472 No comparison group |

CES-D DIS-III-R Trimester 1, 2 or 3 |

None | 8/13 (62%) |

| Scholle et al, 200328 | Quasi-experimental 3 diverse Ob/Gyn practices in USA |

n=583 office practices n=233 hospital clinics n=75 suburban clinic Comparison group = clinics not exposed to intervention |

PHQ-9 ≥22 weeks GA | PHQ-9≥10: on site assessment (most by phone), referral evaluation, case management, engagement strategies | 10/17 (59%) |

| Harvey et al, 201229 | Quasi-experimental Hospital based general practices in Australia |

n=783 n=455 antenatal n=328 PP Comparison group = pre-intervention |

EPDS DASS time 1 (pre-test) 2 (post-test) |

Engagement strategies, provider training, case management, on site assessment, resources, referral, follow-up | 10/18 (55%) |

| Miller et al, 200919 | Quasi-experimental Urban family health center in USA |

n=7,630 Intervention group: n=2,191 Pre-intervention group: n=5,439 |

EPDS First PNV visit 28 wks GA PP visit |

Provider training, referral, on site assessment, telephonic mental health consultation, resources, feedback loop | 7/18 (39%) |

| Rowan et al, 201226 | Quasi-experimental Large obstetric practice in USA |

n=2,199 n=569 with data at 6 week PP No comparison group |

EPDS First PNV 6 weeks PP |

EPDS ≥9: engagement strategies EPDS ≥14: resources, referral, systematic follow-up |

6/17 (35%) |

| Miller et al, 201220 | Quasi-experimental Urban family health center in USA |

n=541 Intervention group: n=400 Pre-intervention group: n=141 Comparison group = historical controls |

PHQ-9 24-28 wks GA 3-8 wks PP |

Intervention group: referral, provider training, case management, on site assessment, resources, telephonic mental health consultation, feedback loop, engagement strategies Pre-intervention group: on site assessment | 5/16 (31%) |

RCT (Randomized controlled trial), PP (postpartum), EPDS (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale), PRIME-MD BHQ (Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders screening questionnaire for depressive symptoms Brief Health Questionnaire), PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire), MINI (Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview), SCID (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV), DASS (Depression Anxiety Stress Scales), DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders), Fourth Edition, BDI (Beck Depression Inventory), CES-D (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale), DIS-III-R (Diagnostic Interview Schedule), IPT (Interpersonal psychotherapy), CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy), GA (Gestational age), PNV (Prenatal visit)

Quality scale rating based on modified Downs and Black criteria. Percentage quality score is total score divided by maximum score possible. Maximum score varies based on the eligible number of items on the rating scale according to study type.

Mean sample ages of women ranged from 24 to 33 years; however this range is limited to studies that reported an average age for the entire sample (n=8).21-24,27,31-33 Several studies did not report participants' ages or other details of participants' characteristics (n=5).3,19,20,26,29 Four studies separated age into categories and did not report the participant's average age.2,25,28,30

The majority of studies (71%) used the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)34 to screen for depression (Tables II and III). Several other studies used the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (n=3)20,28,33 and Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (n=1).27 Some studies supplemented the initial screen with other tools, such as the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI). Only three studies used a structured diagnostic interview to assess for a diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder.3,29,31 One study did not specify a cut off score for depression.29

Table III. Depression Rates According to Screening Tool and Cut-point.

| Depression Screening Tool | Studies Reporting Measure, N (%) | Cut off scores | Time Points for Screening | % With Score Suggestive of Depression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPDS | 12 (71%)2,3,19,21-23,25,26,29,31-33 | 9-13 | First PNV - 6 mos PP‡ | 6.3-29.5% |

| PHQ-9 | 3 (18%)20,28,33 | >10 | Trimester 2 – 8 weeks PP‡‡ | 8.2-20.2% |

| BDI | 1 (6%)23 | Not reported | Pregnancy unspecified | Not used for screening |

| PRIME-MD BHQ | 3 (18%)2,24,30 | 5 DSM IV criteria for MDD | Pregnancy unspecified | Not used for screening |

| CES-D | 1 (6%)27 | ≥16 | Pregnancy unspecified | 20.4% |

EPDS (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale), PRIME-MD BHQ (Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders screening questionnaire for depressive symptoms Brief Health Questionnaire), PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire), BDI (Beck Depression Inventory), DSM-IV=Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, RCT (Randomized controlled trial), MDD (Major Depressive Disorder), CES-D (Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale).

1 study did not specify time of postpartum screen

2 studies did not specify time of postpartum screen

Rates of positive depression scores varied according to the screening tool used (Table III). While the majority of studies screened both during pregnancy and the postpartum period (n=10),2,3,19,20,22-26,31 some only screened during pregnancy (n=3)27,28,30 or in the postpartum period (n=3).21,32,33 A minority of the studies assessed change in depression score over time (n=5)21,23,29,31,33 and those that did used differing approaches with varying results (Appendix 2, available online at http://links.lww.com/xxx).21,26 None of the studies assessed the extent to which depression scores improved to indicate remission of depression.

The majority of studies assessed the extent to which women participated in a mental health assessment (n=15).2,3,19-24,26-29,31-33 Results for treatment participation and depression outcomes differed according to the type and intensity of the intervention (Table IV and Figure II). As demonstrated in Figure II, studies may be placed in three groups: 1) those with no intervention; 2) those with low-intensity interventions that targeted one or two levels of barriers (patient, provider, or practice) to mental health care use; or, 3) those with high-intensity interventions that targeted all three levels of barriers (patient, provider, and practice). As shown in Table II and Figure II, there was a gradient effect associated with these three groups. Screening without any intervention was associated with an average of 22% mental health care use amongst women who screened positive for depression. Studies that targeted one or two levels of barriers were associated with a modest improvement in mental health care use. For example, studies including interventions targeting patients with systematic follow-up, supportive therapy, or support groups were associated with an average mental health care use rate of 31%.21,24-26,29 Those including interventions targeting patient and provider barriers with patient engagement strategies (44%), on-site assessments (49%) and perinatal care provider training (54%) were associated with double the rate of mental health care use. Studies that targeted all three levels of barriers (patient, provider, and practice) to treatment were the most effective as measured by participation in an initial mental health assessment. The two studies that included provision of resources to patients, perinatal care provider training, on-site assessment, and access to mental health consultation for perinatal care providers as components of the intervention were associated with mental health assessment attendance rates of 72%19 and 90%20 as compared to < 1%19 and 0%20 when the clinical site did not provide these services respectively. Overall, the implementation of interventions that targeted multiple barriers were associated with higher rates of mental health care use than screening alone.

Table IV. Mental Health Utilization According to Intervention.

| Intervention Component | Studies reporting measure N (%) |

Screen indicative of depression (% range)* |

Positive screen and referred for treatment (% range)† |

Accepted referral for mental health care (% range)† |

Participated in mental health assessment (% range)† |

Attended follow-up mental health care (% range)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Referral to mental health treatment/evaluation | 12 (70.5%)2,19-21,24-26,28,29,31-33 | 5-29.5% (n=15)3,19-29,31-33 | 1-100% (n=11)2,3,19-21,23,24,27,30-32 | 32.5-98.6% (n=4)2,19,21,29 | 2-90% (n=11)2,19-21,24,26,28,29,31-33 | 0%* (n=1)26 |

| On-site assessment | 9 (52.9%)2,19-21,28,29,31,33 | 8.8-29.5% (n=8)2,19-21,28,29,31,33 | 20-83.3% (n=8)2,19-21,28,29,31,33 | 52-100% (n=4)2,19,21,24 | 25.2-90% (n=8)2,19-21,28,29,31,33 | Not reported |

| Access to mental health consultation for perinatal care providers | 2 (11.7%)19,20 | 8.8-20.5% (n=2)19,20 | 76-83.3% (n=2)19,20 | 72-78% (n=2)19,20 | 72-90% (n=2)19,20 | Not reported |

| Perinatal care provider training | 5 (29.4%)19,20,24,29,33 | 8.8-29.5% (n=5)19,20,24,29,33 | 1-100% (n=2)19,29 | 52% (n=1)29 | 1-90% (n=5)19,20,23,24,31,1 | Not reported |

| Case management | 5 (29.4%)20,21,24,28,29 | 8.8-15% (n=5)20,21,24,28,29 | 1-83.3% (n=5)20,21,24,28,29 | 32.5-52% (n=2)21,29 | 0-90% (n=5)20,21,24,28,29 | Not reported |

| Systematic provision of resources to patients | 9 (52.9%)2,19-21,23,24,26,29,31 | 8.2-30.5% (n=9)2,19-21,23,24,26,29,31 | 1-100% (n=8)2,19-21,24,26,29,31 | 32.5-100% (n=4)2,19,21,24 | 32.5-90% (n=8)2,3,19-21,23,24,30 | Not reported |

| Systematic follow-up with provision of resources/referral to patients | 3 (17.6%)24,26,29 | 11-18.7% (n=3)24,26,29 | Not reported | Not reported | 0-43.2% (n=3)24,26,29 | Not reported |

| Supportive psychotherapy counseling/referral to support group | 2 (11.7%)21,25 | 5-15% (n=1)21,25 | Not reported | 31% (n=1)21 | 15%-30% (n=2)21,25 | Not reported |

| Provider feedback loop | 2 (11.7%)19,20 | 8.8-17.1% (n=2)19,20 | 83.3% (n=1)20 | 72-90% (n=2)19,20 | 72-90% (n=2)19,20 | Not reported |

| Psycho-education / treatment engagement strategies | 7 (41.1%) 20,21,23,26,29,31,33 | 8.8-29.5% (n=7)20,21,23,26,29,31,33 | 8.8-29.5% (n=6)20,21,26,31,33 | 31.9-83.3% (n=3)20,21,29 | 29%-90% (n=6)20,21,26,29,31,33 | Not reported |

| CBT | 1 (5.8%)3 | 13.2% (n=1)3 | 6.1% (n=1)3 | 6.1% (n=1)3 | 2.0% (n=1)3 | 2.0% (n=1)3 |

| None | 3 (17.6%)22,27,30 | 8.5-23% (n=2)22,27 | 33% (n=1)22 | Not reported | 13.8-33% (n=3)22,27,30 | Not reported |

CBT=cognitive behavioral therapy

Denominator = all study participants

Denominator = number participants who screened positive for depression

Figure 2.

Attendance at initial mental health visit according to intervention. *Vertical lines indicate range.

Three studies examining screening and provision of resources (n=3)3,23,28 were associated with a 33.5% average follow-up rate. Two other studies that included psycho-education and engagement strategies, provision of resources and case management were associated with a rate of 63% mental health care follow-up at one month after the screening.21,29

Few studies assessed change in depression score over time (n=4)21,29,31,33 and those that did used differing approaches with varying results (Appendix 2, http://links.lww.com/xxx).

Discussion

Engaging pregnant and postpartum women in mental health care after depression screening is a complex process that requires interventions to address the multiple barriers to mental health care faced by pregnant and postpartum women with depression. We found a two-fold to four fold increase in mental health care use among pregnant and postpartum women associated with interventions that targeted one or two levels of barriers to detecting, assessing, referring and treating depression in perinatal care settings. Strategies that target patient level barriers through patient engagement strategies and resource provision were associated with higher rates of mental health care use than screening alone. Interventions that target all three levels of barriers (patient, provider, and practice) by employing resource provision to patients, perinatal care provider training, and access to mental health consultation were associated with the best mental health care use outcomes. This suggests that building patient, perinatal care provider and practice-level capacity, in addition to screening, is essential to improve mental health care use among pregnant and postpartum women.

We found substantial heterogeneity among studies. While all the included studies assessed mental health treatment use and depression outcomes, they differed in regards to: 1) screening tools; 2) interventions deployed; 3) outcome assessment; and, 4) study design. There was also little to no similarities among the screening tools used. This heterogeneity is consistent with The Agency for Healthcare Research Quality (AHRQ) Comparative Effectiveness Review on the Efficacy and Safety of Screening for Postpartum Depression35 which noted wide variations in postpartum depression (PPD) screening methods and lack of clarity as to what defines the ideal screening tool. Our findings support AHRQ's recommendation for a consensus on a core set of measures that should be consistently reported and compared across all studies.35

Many of the included studies also did not provide a clear operational definition of the intervention. Studies also did not consistently report other important depression related outcomes such as quality of life, daily functioning, perceptions of stigma, and self-efficacy. They also differed in their approaches to measuring mental health care use. Clearly operationalized and described interventions and measures could facilitate comparisons across studies.

Overall, we did not find a correlation between quality ratings of the included studies and mental health care use. The study with the highest quality rating (90%)33 was a cluster RCT design that could serve as a model to strengthen the evidence base. Given the dearth of definitive gold standard randomized controlled trials, our inclusion of non-controlled study designs allowed us to examine which intervention components lead to mental health care use after screening. RCT study designs that include formal comparison groups, follow-up data, and assessment of change in depression outcomes and rates of remission are needed to determine whether improved treatment leads to improved depression outcomes.

Despite limitations among the available studies, we conclude that there is a dose-response effect. Interventions that include more intense strategies that target multiple barriers to depression care are associated with increased mental health care use among pregnant and postpartum women who screen positive for depression (Figure II). We systematically examined the various mental health use outcomes that need to be considered. We included a wide range of relevant outcomes and study designs to disentangle which interventions help engage women in mental health care. Although the evidence is incomplete, based on our assessment of the aggregate of the evidence available to date, we conclude that the benefits of screening outweigh the risks when the provision of appropriate mental health assessment and treatment can be ensured. Screening coupled with provision of resources to women, perinatal care provider training, on-site assessment, and access to mental health consultation is associated with the majority of women entering mental health treatment. While definitive studies are still needed, intervention components that enhance patient, perinatal care provider and practice-level capacities for depression detection, assessment, and treatment, appear promising. Interventions that do not include these components are associated with much lower rates of treatment entry.

To inform the development of guidelines, policies and legislation, future screening efforts, and screening programs should develop mechanisms that assess the context in which the screening is implemented. Important contextual factors include the ability of front line providers and practices to detect and manage depression. Perinatal care systems, practices, and individual providers considering initiating screening need to ensure that a system is in place to link women with care. Future studies should also assess whether increased mental health care use leads to a reduction in depression severity because clinical improvement of depression ultimately justifies the utility of screening. Multi-disciplinary interventions, particularly those that build patient, perinatal provider and practice-level capacity to detect and address depression, need to be rigorously developed, evaluated, and disseminated. To promote maternal and child health, it is imperative that we harness the perinatal period and perinatal care setting as an opportunity to screen, diagnose, and treat depression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Byatt has received grant funding/support for this project from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number KL2TR000160. Dr. Allison received grant funding/support for this project from the National Institute of Minority Health And Health Disparities of the NIH under Award Number P60MD006912. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Financial Disclosure: Dr. Byatt has received salary and funding support from the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health via the Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Project for Moms (MCPAP for Moms) and is the Medical Director of MCPAP for Moms. Dr. Moore Simas serves as a representative to the MA section of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (MA-ACOG) on the MA Governor's Commission on Postpartum Depression, and serves as an Ob/Gyn consultant to MCPAP for Moms.

Footnotes

The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Nancy Byatt, Department of Psychiatry and Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Leonard L. Levin, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Douglas Ziedonis, Department of Psychiatry, University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Tiffany A. Moore Simas, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Pediatrics, University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Jeroan Allison, Department of Quantitative Heath Sciences, University of Massachusetts Medical School.

References

- 1.Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1071–83. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith MV, Shao L, Howell H, Wang H, Poschman K, Yonkers KA. Success of mental health referral among pregnant and postpartum women with psychiatric distress. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31:155–62. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter FA, Carter JD, Luty SE, Wilson DA, Frampton CM, Joyce PR. Screening and treatment for depression during pregnancy: a cautionary note. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39:255–61. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amercican College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 453. Screening for depression during and after pregnancy. 2010 Feb; doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d035aa. Report No.: 453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. Committee opinion no. 630. Screening for Perinatal Depression. 2015 May; doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000465192.34779.dc. 2015. Report No.: 631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kozhimannil KB, Adams AS, Soumerai SB, Busch AB, Huskamp HA. New Jersey's efforts to improve postpartum depression care did not change treatment patterns for women on medicaid. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:293–301. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.United States Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for depression in adults: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Int Med. 2009:784–92. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-11-200912010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Association of Women's Health Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses. The role of the nurse in postpartum mood and anxiety disorders. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 9.American College of Nurse-Midwives. Depression in women: position statement. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 10.The PNP's role in supporting infant and family well-being during the first year of life. J Pediatr Health Care. 2003;17:19A–20A. doi: 10.1067/mph.2003.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thombs BD, Arthurs E, Coronado-Montoya S, et al. Depression screening and patient outcomes in pregnancy or postpartum: a systematic review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2014;76:433–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hewitt CE, Gilbody SM. Is it clinically and cost effective to screen for postnatal depression: a systematic review of controlled clinical trials and economic evidence. BJOG. 2009;116:1019–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paulden M, Palmer S, Hewitt C, Gilbody S. Screening for postnatal depression in primary care: cost effectiveness analysis. BMJ. 2009;339:b5203. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b5203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yawn BP, Olson AL, Bertram S, Pace W, Wollan P, Dietrich AJ. Postpartum Depression: Screening, Diagnosis, and Management Programs 2000 through 2010. Depress Res Treat. 2012;2012:363964. doi: 10.1155/2012/363964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atkins D, Siegel J, Slutsky J. Making policy when the evidence is in dispute. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24:102–13. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Counsell C. Formulating questions and locating primary studies for inclusion in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:380–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-5-199709010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52:377–84. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacLehose RR, Reeves BC, Harvey IM, Sheldon TA, Russell IT, Black AM. A systematic review of comparisons of effect sizes derived from randomised and non-randomised studies. Health Technol Assess. 2000;4:1–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller L, Shade M, Vasireddy V. Beyond screening: assessment of perinatal depression in a perinatal care setting. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2009;12:329–34. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller LJ, McGlynn A, Suberlak K, Rubin LH, Miller M, Pirec V. Now what? Effects of on-site assessment on treatment entry after perinatal depression screening. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21:1046–52. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen H, Wang J, Ch'ng YC, Mingoo R, Lee T, Ong J. Identifying mothers with postpartum depression early: integrating perinatal mental health care into the obstetric setting. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2011;2011:309189. doi: 10.5402/2011/309189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goodman JH, Tyer-Viola L. Detection, treatment, and referral of perinatal depression and anxiety by obstetrical providers. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19:477–90. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reay R, Matthey S, Ellwood D, Scott M. Long-term outcomes of participants in a perinatal depression early detection program. J Affect Disord. 2011;129:94–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yonkers KA, Smith MV, Lin H, Howell HB, Shao L, Rosenheck RA. Depression screening of perinatal women: an evaluation of the healthy start depression initiative. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:322–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.3.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burton A, Patel S, Kaminsky L, et al. Depression in pregnancy: time of screening and access to psychiatric care. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24:1321–4. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2010.547234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rowan P, Greisinger A, Brehm B, Smith F, McReynolds E. Outcomes from implementing systematic antepartum depression screening in obstetrics. Archives of women's mental health. 2012;15:115–20. doi: 10.1007/s00737-012-0262-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marcus SM, Flynn HA, Blow FC, Barry KL. Depressive symptoms among pregnant women screened in obstetrics settings. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2003;12:373–80. doi: 10.1089/154099903765448880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scholle SH, Haskett RF, Hanusa BH, Pincus HA, Kupfer DJ. Addressing depression in obstetrics/gynecology practice. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003;25:83–90. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(03)00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harvey ST, Fisher LJ, Green VM. Evaluating the clinical efficacy of a primary care-focused, nurse-led, consultation liaison model for perinatal mental health. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2012;21:75–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2011.00766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith MV, Rosenheck RA, Cavaleri MA, Howell HB, Poschman K, Yonkers KA. Screening for and detection of depression, panic disorder, and PTSD in public-sector obstetric clinics. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:407–14. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flynn HA, O'Mahen HA, Massey L, Marcus S. The impact of a brief obstetrics clinic-based intervention on treatment use for perinatal depression. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2006;15:1195–204. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nelson DB, Freeman MP, Johnson NL, McIntire DD, Leveno KJ. A prospective study of postpartum depression in 17 648 parturients. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2013;26:1155–61. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.777698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yawn BP, Dietrich AJ, Wollan P, et al. TRIPPD: a practice-based network effectiveness study of postpartum depression screening and management. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:320–9. doi: 10.1370/afm.1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Efficacy and Safety of Screening for Postpartum Depression. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.