Abstract

Despite major advances in identifying pathophysiological mechanisms of acute kidney injury (AKI), no definitive therapeutic or preventive modalities have been developed with the exception of dialysis. One possible approach is the control of inflammation and AKI through activation of the neuro-immune axis. The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway is thought to contribute to the homeostatic response to inflammation-related disorders and forms the basis for recent approaches to therapeutic intervention. The concept is based on the emerging understanding of the interface between the nervous and immune systems. In the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway, the efferent vagus nerve indirectly stimulates the CD4+ T cells in the spleen. The CD4+ T cells produce acetylcholine, which stimulates alpha 7 nicotinic receptors (α7nAch) on macrophages. Activation of the α7nAch receptors on macrophages activates NF-κβ and elicits an anti-inflammatory response. Recently we demonstrated the effect of a non-pharmacologic, noninvasive, ultrasound-based method to prevent renal ischemia-reperfusion injury and sepsis-induced AKI in mice. Our data suggest that ultrasound-induced tissue protection is mediated through the activation of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. In addition, nicotinic receptor agonists and ghrelin, a neuropeptide, were reported to prevent AKI possibly through a mechanism closely linked with vagus nerve stimulation. Based on the studies focusing on inflammation and the observations regarding kidney injury, we believe that activating the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway will be a new modality for the prevention and treatment of AKI.

Keywords: Neuroimmunomodulation, immunity, inflammation, acute renal failure, vagus nerve, kidney, autonomic nervous system

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common and major concern in hospitalized patients because of its high morbidity and mortality [1]. Despite recent attempts, the current therapies for AKI are mainly supportive, and there are no definitive therapeutic or protective modalities available for AKI despite research that has identified many potential pathogenic mechanisms, such as inflammation and local and systemic factors. Among them, neural control of inflammation is emerging as an important concept, yet very little is known regarding how neural factors can modulate inflammation that develops after AKI.

The nervous and immune systems have been thought to serve separate and distinct functions, however recently there has been considerable evidence that indicate these two systems are linked to maintain normal homeostasis as well to respond to stress and pathophysiological conditions characteristic of certain disorders [2]. Immune cells express receptors for neurotransmitters that permit control of immune response to infection by the central and peripheral nervous system. Some immune cells can synthesize and secrete neurotransmitters, such as acetylcholine-secreting lymphocytes. One well-known mechanism of neuroimmune control of inflammation involves the adrenal glands, i.e. the hypothalamic– pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis [3]. In response to stress messages from the brain, the adrenal glands release hormones into the blood and these affect almost all types of immune cells. The immune cells perform immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory functions through various genomic and non-genomic mechanisms [3]. Neuropeptides, a type of neuromodulator released from neurons, have both pro- and anti-inflammatory effects [4]. In addition, recent advances, demonstrating a further link between the nervous and immune systems, revealed that vagus nerve stimulation regulates the immune system [5] and serves a target for neuroimmunomodulation of peripheral nerve activity in disorders such as myocardial infarction, colitis, pancreatitis, ischemia-reperfusion injury, sepsis, arthritis and others [6].

Stimulating the vagus nerve, as a means of modulating peripheral nerve activity, suppresses inflammation, and clinical trials examining the effects of vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) on inflammatory disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis [7] and inflammatory bowel diseases are ongoing [8]. Recent studies show that activation of both pro- and anti-inflammatory immune responses occurs promptly after sepsis [9]. The balance of these opposing responses may lead to a favorable outcome. A hyper-proinflammatory response may lead to early death, however it is thought that this response is controlled in part by an efferent arm of the inflammatory reflex, referred to as the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway, which involves norepinephrine and acetylcholine, neurotransmitters of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system, respectively. In this review we highlight the neuroimmune axis in AKI and the possibility of neural modulation of this pathway for future treatment.

Cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway

Recent studies support the concept that a potent anti-inflammatory mechanism is mediated by the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway [10]. Stimulation of efferent vagus nerve activity is known to cause decreased heart rate, induction of gastric motility, dilation of arterioles and constriction of pupils. But in addition, VNS has been demonstrated to inhibit the inflammatory response [10]. In this study electrical stimulation was performed 30 min before systemic administration of lipopolysaccharide (LPS 15 mg/kg, i.v.), which is used to mimic sepsis in rats. Blood was collected from the right carotid artery 1 hour after LPS administration and serum tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) concentrations were quantified. Activation of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway by direct electrical stimulation of the efferent vagus nerve inhibits the synthesis of TNFα, a cytokine involved in systemic inflammation that is mainly produced by macrophages. Vagotomy significantly exacerbates TNFα responses to inflammatory stimuli and increases mortality of animals injected with endotoxin (LPS). A key role of the alpha 7 subunit of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7nAChR) in controlling inflammation was identified through the use of mice deficient of α7nAChRs[11]. Electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve inhibited TNFα synthesis in wild-type mice, but failed to inhibit TNFα synthesis in α7nAChR-deficient mice. Furthermore, macrophages derived from α7nAChR-deficient mice were refractory to cholinergic agonists, whereas those from wild-type mice produce TNFα in the presence of nicotine or acetylcholine [11].

In this reflex pathway, afferent signals to the brain are initiated by damage-associated molecular pattern molecules (DAMPs), including endogenous products released by dying cells, and/or pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) from bacterial pathogens that activate toll like receptors and invoke afferent signals from the vagus nerve to the brain. The brain sends efferent signals to inhibit cytokine production via pathways dependent on α7nAChR expressed on macrophages and other cells [6].

Immune cells in spleen play important roles in VNS

The spleen plays an important role in the immune system and was found to be essential for the inhibition of systemic inflammation by VNS [12]. To explore the relationship between the anti-inflammatory pathway and organs, organ TNFα concentrations during lethal endotoxemia in rats were measured [12]. The spleen was revealed to be an important source of TNFα production that is regulated by VNS. VNS stimulation of TNFα production is attenuated in splenectomized animals. Moreover, VNS in α7nAChR-deficient mice failed to inhibit TNFα production in the spleen. Considering these results, α7nAChR-positive cells in spleen appear to be important for the anti-inflammatory effect produced by VNS.

Parasympathetic neurons, such as the vagus, release acetylcholine (ACh) from their nerve terminals. Although the spleen contains acetylcholine (ACh), the vagus nerve does not appear to innervate the spleen [13]. Nerve fibers in spleen, originating in the celiac ganglion, are adrenergic, not cholinergic, and produce norepinephrine as the primary neurotransmitter. Unexplained was the source of splenic ACh following inflammatory reflex stimulation. Rosas-Ballina et al. found that CD4-positive T cells released ACh in response to stimulation by norepinephrine [14]. Within minutes after electrical VNS, ACh levels were elevated in the spleen and reached peak levels within 20 min. To identify the cells that produce ACh, choline acetyltransferase (ChAT)-eGFP mice, which express enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) under the control of transcriptional regulatory elements for ChAT, the enzyme that catalyzes the biosynthesis of ACh, were used. Flow cytometry revealed that CD4-positive T cells expressing ChAT can be defined phenotypically as CD44high CD62Llow memory T cells.

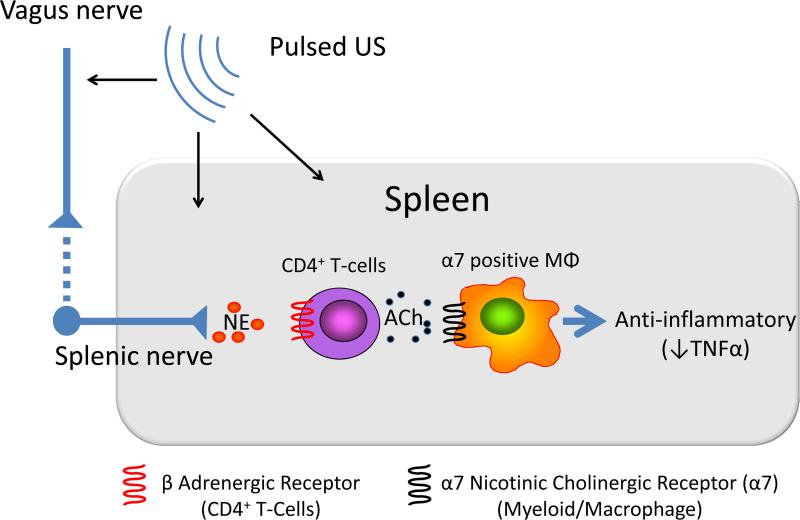

Thus ACh-synthesizing CD4+ T cells appear to be an important link between the vagus nerve and the anti-inflammatory role of the spleen [14]. ACh, released from these cells binds to α7nAChR on macrophages and suppresses TNFα release (Figure). Although many of the functional components of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway have been defined, including activation of CD4+ T cells in spleen in response to efferent vagus nerve stimulation, the precise mechanisms have yet to be identified.

Figure. Cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway.

The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway links the nervous system and immune system. Activation of the pathway by vagal nerve stimulation suppresses inflammation and enhancing this pathway protects kidneys from acute injury. The efferent vagus nerve stimulates CD4-positive T cells in spleen via the splenic sympathetic nerve. Release of norepinephrine binds to beta adrenergic receptors on CD4+ T cells, which then elicits release of acetylcholine (ACh). ACh binding to alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (α7nAChRs) on macrophages produces an anti-inflammatory response, such as TNFα suppression. Ultrasound prior to kidney ischemia and reperfusion attenuates injury through either a neuronal or neuronal independent pathway that requires the spleen, CD4+ T cells, and α7nAChRs expressed on bone marrow-derived cells (17,18).

Neuroimmune control of inflammation in AKI

Although a direct effect of VNS in modulating AKI has not yet been reported, there is one paper that supports the role of the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway in AKI [15]. They examined the effects of cholinergic stimulation using agonists, nicotine (1 mg/kg) or GTS-21 (10 mg/kg), in renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats [15]. Prior administration of either agonist (20 minutes before clamping the renal vessel) significantly attenuated renal dysfunction and tubular necrosis induced by renal ischemia. GTS-21 administered 2 hour after reperfusion did not significantly improve renal function. In addition, they showed that TNFα protein expression and leukocyte infiltration of the kidney were markedly reduced by prior cholinergic agonist treatment.

Ghrelin, a peptide produced by cells in the gastrointestinal tract and that functions as a neuromodulator, attenuates AKI [16,17]. In the ischemia-reperfusion injury model of AKI in rats (60 min ischemia and 24 hr reperfusion), , kidney injury was attenuated by human ghrelin (4 nmol/rat) when slowly infused over 30 minutes soon after reperfusion; the protective effect was abolished by prior vagotomy [16]. Ghrelin (100 μg/kg/ip) had similar protective effects in a cecal ligation puncture–induced sepsis model of AKI in rats [17]. These studies demonstrate that ghrelin, a neuropeptide regulated by the vagus, may have potent effects to attenuate AKI.

Ultrasound treatment modulates the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway and attenuates AKI

Recently we showed that prior ultrasound application can protect kidneys from ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice [18]. In these studies we used a clinical Sequoia 512 ultrasound machine with a 15L8w transducer (Acuson, Malvern, PA). The ultrasound treatment consisted of ultrasound pulses administered with a bursting mechanical index of 1.2 at a frequency of 7 MHz. Ultrasound pulses were 1 second in duration and were applied once every 6 seconds for 2 minutes. The protective effect of ultrasound was lost in Rag1-deficient mice, which lack T and B lymphocytes. Adoptive transfer of wild-type CD4+ T cells into these mice prior to ultrasound rescued the tissue protective effect, thereby demonstrating the requirement for CD4+ T cells. In addition, when the spleen was removed before CD4+ T cell transfer, this protection again was abolished [18]. Splenic sympathectomy with splenic injections of 6-hydroxydopamine a neurotoxin that selectively destroys catecholaminergic nerve terminals, exacerbates renal ischemia-reperfusion injury [19]. These results, taken together, reveal that the spleen, splenic sympathetic nerve and CD4+ T cells mediate the protective effects of ultrasound. In addition, loss of α7nACh response, either by pharmacologic antagonism or genetic deficiency of the α7nAChR on bone marrow-derived cells, blocked the protective effect of ultrasound [18]. Ultrasound protection was associated with reduced expression of circulating and kidney-derived cytokines such as TNFα. Also the protective effect of ultrasound was confirmed in a cecal ligation puncture–induced sepsis model [19] as well as in a pigs subjected to ischemia-reperfusion injury (unpublished observations, J. Gigliotti and M. D. Okusa, 2015) These results support the concept that prior ultrasound prevents AKI through the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway.

Clinical use of vagus nerve stimulator

VNS therapy, by using a device that is surgically implanted to stimulate the vagus nerve, was approved for the treatment of medically refractory epilepsy in Europe in 1994 and in the United States in 1997 by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The FDA approved VNS therapy for treatment-resistant depression in 2005. As of August 2014, over 100,000 VNS devices were implanted in more than 75,000 patients worldwide [20] and clinical trials on a wide variety of disorders, such as heart failure, hypertension, inflammation and diabetes, are on-going. The pulse generator is implanted under the left clavicle, and the stimulation lead is wrapped around the left vagus nerve in the neck [21]. Postoperative infections occur in approximately 3% of patients but can be treated with oral antibiotics. Side effects are related to the stimulation. Cough, hoarseness, voice alteration, and paresthesias are commonly observed, and these side effects tend to diminish with time.

Recently two non-invasive external devices, which can stimulate the vagus nerve through the skin, have been developed [22]. One can provide transcutaneous VNS by using a dedicated intra-auricular electrode (like an earphone) that stimulates the auricular branch of the vagus nerve. Another can deliver a proprietary, low-voltage electrical signal to the cervical vagus nerve. The effect of these two devices is currently being investigated.

Conclusion

The neuroimmune pathway is a critical interface that permits rapid modulation of the immune system through a reflex pathway referred to as the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. This pathway provides an exciting new target with the potential for modulating a number of inflammatory conditions, including myocardial infarction, colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, acute kidney injury and others. In most cases to date, invasive procedures are necessary. Direct vagal nerve stimulation or pharmacological agents have been used but may be limited by the invasiveness of the procedure to insert devices and toxicity associated with pharmacological agents. Our studies demonstrate that pulses of ultrasound, a noninvasive, nonpharmacological tool, can activate the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway and thereby largely attenuate acute kidney injury. Additional studies will lead to further understanding of neuroimmunodulatory mechanisms of inflammatory disorders and to improved neuroimmunodulatory therapies to preserve organ function.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award numbers R01DK085259, R01DK062324, and T32-DK072922, by the National Center for Research Resources of the NIH under award number S10 RR026799 (M.D.O) and by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Postdoctoral Fellowships for Overseas Researchers (T.I).

References

- 1.Uchino S. Acute renal failure in critically ill patients: A multinational, multicenter study. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;294:813–818. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.7.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Procaccini C, Pucino V, De Rosa V, Marone G, Matarese G. Neuro-endocrine networks controlling immune system in health and disease. Front Immunol. 2014;5:143. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellavance MA, Rivest S. The hpa - immune axis and the immunomodulatory actions of glucocorticoids in the brain. Front Immunol. 2014;5:136. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pinter E, Pozsgai G, Hajna Z, Helyes Z, Szolcsanyi J. Neuropeptide receptors as potential drug targets in the treatment of inflammatory conditions. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;77:5–20. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersson U, Tracey KJ. Reflex principles of immunological homeostasis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:313–335. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tracey KJ. Physiology and immunology of the cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007;117:289–296. doi: 10.1172/JCI30555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koopman FA, Schuurman PR, Vervoordeldonk MJ, Tak PP. Vagus nerve stimulation: A new bioelectronics approach to treat rheumatoid arthritis? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2014;28:625–635. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2014.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matteoli G, Boeckxstaens GE. The vagal innervation of the gut and immune homeostasis. Gut. 2013;62:1214–1222. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hotchkiss RS, Monneret G, Payen D. Sepsis-induced immunosuppression: From cellular dysfunctions to immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:862–874. doi: 10.1038/nri3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borovikova LV, Ivanova S, Zhang M, Yang H, Botchkina GI, Watkins LR, Wang H, Abumrad N, Eaton JW, Tracey KJ. Vagus nerve stimulation attenuates the systemic inflammatory response to endotoxin. Nature. 2000;405:458–462. doi: 10.1038/35013070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang H, Yu M, Ochani M, Amella CA, Tanovic M, Susarla S, Li JH, Yang H, Ulloa L, Al-Abed Y, Czura CJ, Tracey KJ. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha7 subunit is an essential regulator of inflammation. Nature. 2003;421:384–388. doi: 10.1038/nature01339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huston JM, Ochani M, Rosas-Ballina M, Liao H, Ochani K, Pavlov VA, Gallowitsch-Puerta M, Ashok M, Czura CJ, Foxwell B, Tracey KJ, Ulloa L. Splenectomy inactivates the cholinergic antiinflammatory pathway during lethal endotoxemia and polymicrobial sepsis. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2006;203:1623–1628. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martelli D, McKinley MJ, McAllen RM. The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway: A critical review. Auton Neurosci. 2014;182:65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosas-Ballina M, Olofsson PS, Ochani M, Valdes-Ferrer SI, Levine YA, Reardon C, Tusche MW, Pavlov VA, Andersson U, Chavan S, Mak TW, Tracey KJ. Acetylcholine-synthesizing t cells relay neural signals in a vagus nerve circuit. Science. 2011;334:98–101. doi: 10.1126/science.1209985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yeboah MM, Xue X, Duan B, Ochani M, Tracey KJ, Susin M, Metz CN. Cholinergic agonists attenuate renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Kidney Int. 2008;74:62–69. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rajan D, Wu R, Shah KG, Jacob A, Coppa GF, Wang P. Human ghrelin protects animals from renal ischemia-reperfusion injury through the vagus nerve. Surgery. 2012;151:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khowailed A, Younan SM, Ashour H, Kamel AE, Sharawy N. Effects of ghrelin on sepsis-induced acute kidney injury: One step forward. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s10157-014-1006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gigliotti JC, Huang L, Ye H, Bajwa A, Chattrabhuti K, Lee S, Klibanov AL, Kalantari K, Rosin DL, Okusa MD. Ultrasound prevents renal ischemia-reperfusion injury by stimulating the splenic cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2013;24:1451–1460. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013010084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gigliotti JC, Huang L, Bajwa A, Ye H, Mace EH, Hossack JA, Kalantari K, Inoue T, Rosin DL, Okusa MD. Ultrasound modulates the splenic neuroimmune axis in attenuating aki. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2015 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014080769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ben-Menachem E, Revesz D, Simon BJ, Silberstein S. Surgically implanted and non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation: A review of efficacy, safety and tolerability. Eur J Neurol. 2015 doi: 10.1111/ene.12629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stacey WC, Litt B. Technology insight: Neuroengineering and epilepsy-designing devices for seizure control. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2008;4:190–201. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Howland RH. Vagus nerve stimulation. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep. 2014;1:64–73. doi: 10.1007/s40473-014-0010-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]