Abstract

There is extensive evidence that accumulation of mononuclear phagocytes including microglial cells, monocytes and macrophages at sites of β-amyloid (Aβ) deposition in the brain is an important pathological feature of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related animal models, and the concentration of these cells clustered around Aβ deposits is several folds higher than in neighboring areas of the brain [1-5]. Microglial cells phagocytose and clear debris, pathogens and toxins, but they can also be activated to produce inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and neurotoxins [6]. Over the past decade, the roles of microglial cells in AD have begun to be clarified and we proposed that these cells play a dichotomous role in the pathogenesis of AD [4, 6-11]. Microglial cells are able to clear soluble and fibrillar Aβ, but continued interactions of these cells with Aβ can lead to an inflammatory response resulting in neurotoxicity. Inflammasomes are inducible high molecular weight protein complexes that are involved in many inflammatory pathological processes. Recently, Aβ was found to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in microglial cells in vitro and in vivo thereby defining a novel pathway that could lead to progression of AD [12-14]. In this manuscript we review possible steps leading to Aβ-induced inflammasome activation and discuss how this could contribute to the pathogenesis of AD.

Keywords: Microglia, Macrophage, NLRP3 inflammasome, β-amyloid, Alzheimer’s disease

Function of microglial cells in the brain

Five to twelve percent of all cells in the mouse brain are microglial cells, depending on the brain region [15]. Because of their immunomodulatory function they are considered the resident macrophages of the brain. Using direct RNA sequencing, our group found important differences in receptor expression between microglial cells and peripheral monocytes and macrophages [16]. However, in spite of these differences, microglial cells share a myeloid origin and several similarities in their receptor repertoire with peripheral monocytes and macrophages. All three cell types also share the ability to activate several inflammatory pathways in response to injurious stimuli.

In general, microglial cells constantly sense and screen the environment with their processes. They are able to adopt an amoeboid shape, migrate to the location of the insult and become activated [17]. Activated microglial cells are found in states of infection and trauma but also neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson disease, prion disease and AD. Elevated levels of pro-inflammatory mediators have been found in all of these conditions [18-20]. The production of mediators such as cytokines, chemokines, reactive oxygen species and nitrogen monoxide [9, 21] helps to attract more microglial cells and possibly peripheral monocytes and ultimately could lead to the removal of pathogens and other toxic stimuli.

Microglia and Aβ

Microglial cells, monocytes and macrophages express receptors that promote phagocytosis of Aβ, and intracellular Aβ deposits have been observed in mononuclear phagocytes in AD brains. These cells also express Aβ degrading enzymes further contributing to Aβ clearance. In mouse models of AD we found that uptake of Aβ is mediated via the class A scavenger receptor Scara1, and deficiency in this receptor is associated with increased mortality and Aβ accumulation in these mice [8, 10] further supporting the paradigm that these cells play a neuroprotective role by promoting Aβ phagocytosis, degradation and clearance. On the other hand, we also found that the interaction of Aβ with a receptor complex that includes the pattern recognition receptor CD36 and a heterodimer composed of the Toll-like receptors (TLR) 4 and 6, is required for activation of microglial cells and the production of inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and neurotoxins [9, 11]. Following Aβ binding to this receptor complex, intracellular signaling leads to the translocation of nuclear factor κB (NFκB) from the cytoplasm into the nucleus [22] but also activation of cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA)/phosphorylated cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) [23] resulting in the transcription of several pro-inflammatory cytokines, NO-Synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 [24, 25]. Recently, an alternative intracellular signaling pathway that is downstream from Aβ binding came into focus: the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome [13, 14].

The NLRP3 inflammasome

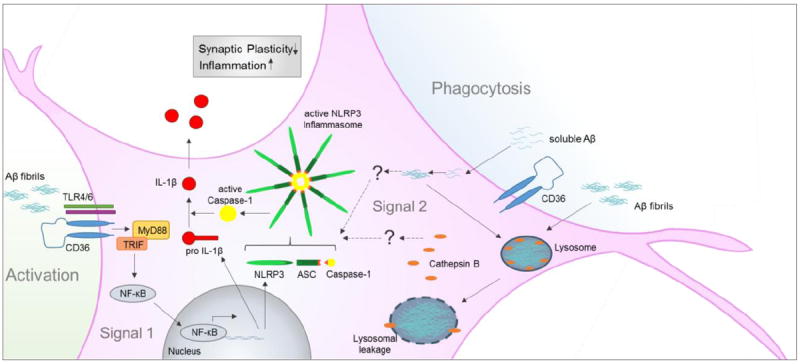

Inflammasomes are inducible high molecular weight protein complexes that were described first by Martinon et al. in 2002 [26]. Four different inflammasomes and their activators have been well characterized so far: NLRP1 [27], NLRP3 [28], NLRC4 [29] and AIM2 [30]. The NLRP3 inflammasome in particular seems to be involved in many pathological mechanisms, since it is activated by several microbes [31, 32], urate crystals [33], cholesterol crystals [34] and aggregated Aβ [12]. The NLRP3 inflammasome, is an intracellular protein complex consisting of the sensor protein NLRP3, the adaptor protein Apoptosis associated Speck-like protein containing a caspase activating and recruitment domain (ASC) and pro caspase-1. Assembly and activation of this complex leads to the cleavage of pro caspase-1 to active caspase-1 (Figure 1). Active caspase-1 in turn cleaves and thereby activates pro-inflammatory cytokines of the IL-1β family. IL-1β as well as IL-18 are synthesized as inactive precursors and undergo posttranslational modifications to become active cytokines [35]. IL-1β is a very potent pyrogenic cytokine and therefore its production and release has to be tightly controlled. In the central nervous system, IL-1β seems to impact long-term potentiation and synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus where memory is consolidated [36].

Figure 1.

Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by Aβ. Both, soluble and fibrillar Aβ can contribute to Inflammasome activation. Aβ fibrils cause activation of microglial cells and therefore provide signal 1 via NF-κB transcription of NLRP3 and pro IL-1β. Signal 2 can either be provided by intracellular aggregation of soluble Aβ or by lysosomal rupture through phagocytosed Aβ fibrils. Both events are leading to the formation of the active NLRP3 inflammasome. Active Caspase-1 finally cleaves pro IL-1β to active IL-1β which is released to the extracellular space.

Two steps are necessary to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome: The first step involves ‘priming’ of the inflammasome, and is the result of disinhibition and nuclear translocation of NF-κB which leads to the transcription of NLRP3 itself and pro IL-1β, both prerequisites for the actual activation of the inflammasome [37, 38]. Many signaling pathways induced by a plethora of stimuli converge in the activation of NF-κB – the most prominent stimuli being LPS that signals via TLR4/CD14 [39]. A much faster way to make NLRP3 available is the deubiquitination of NLRP3 which is suggested to be dependent on mitochondrial ROS activity [40]. The second step of NLRP3 activation is the oligomerization of NLRP3 and the assembly with ASC and pro caspase-1. NLRP3 has been shown to sense putative ligands with its C-terminal leucine-rich repeats and self-oligomerizes via its nucleotide binding domain NACHT [41]. Upon oligomerization, ASC joins the complex and recruits caspase-1 via its caspase recruitment and activating domain (CARD) [42]. In addition, data from murine macrophages indicate that ASC specks can transmit inflammasome activation from cell-to-cell in a prion-like manner [43, 44].

Because inflammasome activation is involved in many pathological processes, attention has been shifting lately to understanding mechanisms of inflammasome regulation. Yan et al. found that dopamine serves as an endogenous inhibitor of the NLRP3 inflammasome [45]. This dopamine effect may be mediated via dopamine receptor 1 which is expressed on many subsets of immune cells including microglial cells [46]. The proposed underlying mechanism of NLRP3 inhibition in this context is ubiquitination and autophagy-mediated degradation of NLRP3 mediated by increased levels of cAMP as described earlier by Lee et al. [47]. In addition, to such endogenous regulatory pathways, Coll et al. characterized a very specific NLRP3 small inhibitor [48]. MCC950, a diarylsulfonylurea-containing compound, blocked NLRP3 inflammasome activation induced by ATP, Nigericin and urate crystals in vitro in human and murine macrophages and delayed the onset and slowed the progression of experimental autoimmune encephalitis, an in vivo mouse model of multiple sclerosis. This inhibitor could be used to study the suitability of NLRP3 as a therapeutic target in many diseases.

The NLRP3 inflammasome in AD

Elevated levels of IL-1β, an endproduct of inflammasome activation have been reported in brains of AD patients as far back as 1989 [49]. It took nearly three decades to identify a potential pathway that could explain such elevated levels, when Aβ was identified as an inflammasome activator [12]. Halle et al proposed that phagocytosis of Aβ is the first step in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Such activation required priming of bone-marrow derived macrophages and microglia with interferon-γ or LPS before uptake of Aβ fibrils. Inhibition of phagocytosis with cytochalasin D abrogated inflammasome activation by Aβ fibrils. Following their phagocytosis, Aβ fibrils localize in intracellular lysosomes, compromising the membrane of these lysosomes and leading to the release cathepsin B, a lysosomal proteolytic enzyme, into the cytosol, thereby activating the inflammasome (Figure 1). The mechanisms by which cathepsin B activates the inflammasome and whether this phenomenon occurs in AD patients or AD animal models is not clear. Data from Aβ treated rat primary microglial cells suggest an inhibitory role for NLRP10 in this context [50]. NLRP10 inhibits the formation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by interacting with ASC. Upon treatment with a cocktail of aggregated Aβ1-42 and Aβ1-40 NLRP10 is degraded, probably by cathepsins, allowing the NLRP3 inflammasome protein complex to be formed.

Sheedy et al. suggested that the pattern recognition receptor CD36 is a possible receptor for soluble Aβ that conveys the signal from Aβ to the inflammasome in the aforementioned two-step manner [14]. CD36 seems to be responsible for priming of the cells through activation of the receptor complex CD36/TLR4/6, subsequent translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus and transcription of NLRP3 and pro IL-1β (Figure 1). The mechanism by which soluble Aβ leads to the assembly of the NLRP3 inflammasome is not fully understood. Sheedy et al. show intracellular formation of Aβ fibrils and lysosomal location after three hours of treatment with soluble Aβ, but they did not determine lysosomal integrity or the levels of cathepsin B. Aβ treatment of cells obtained from CD36-/- mice or pre-treatment with Congo red that interferes with the formation of β-sheets, reduces IL-1β secretion. However, in this study murine bone-marrow derived macrophages were used and not immune cells isolated from the brain.

In 2013 Heneka et al. showed enhanced caspase-1 activation in human brains from patients suffering from mild cognitive impairment and AD. They also found that NLRP3 or Caspase-1 deficiency in mice that carry mutations associated with familial AD (APP/PS1) showed improvements in cognitive decline [13]. In addition, APP/PS1/Nlrp3-/- mice had reduced hippocampal and cortical Aβ deposition, although the processing and expression of the amyloid precursor protein was not affected. Using methoxy-XO4, a fluorescent molecule that binds Aβ with high affinity, injected intraperitoneally into adult APP/PS1/ Nlrp3-/- and APP/PS1/Casp1-/- mice, the authors showed a two-fold increase in Aβ phagocytosis by microglial cells from these mice compared to APP/PS1 mice. This finding suggests that NLRP3 inflammasome activation reduces phagocytosis of Aβ by microglial cells. NLRP3 activation could therefor contribute to the pathogenesis of AD via two processes. First it can regulate production of IL-1 and possibly neurotoxins causing neuronal degeneration. Second, it can reduce Aβ clearance leading to enhanced deposition, thereby creating a self-perpetuating loop that culminated in AD progression.

A second pathway that might contribute to inflammasome activation in AD brains involves extracellular ATP and the purinergic receptor P2X7. Extracellular ATP may be released by dying or degenerating neurons and activates P2X7 [28, 51]. P2X7, which is expressed on microglia [16], in turn activates the NLRP3 inflammasome [28, 51]. Interestingly, P2X7 expression is increased in human AD brains [52]. Based on these reports it is possible that signaling via P2X7 provides a second mechanism for NLRP3 inflammasome activation in addition to Aβ-induced signaling [53].

Open questions and caveats

Because microglial cells are the resident mononuclear phagocytes of the CNS, most published studies refer to Aβ-associated mononuclear phagocytes as microglia. Work done in animal models of Aβ deposition suggested that in addition to microglia, some Aβ-associated mononuclear phagocytes are blood or bone marrow derived monocytes [54, 55]. Our own work using the Tg2576 mouse model of Aβ deposition supported the possibility that blood-borne monocytes accumulate in the brains of these mice as the disease progresses [8]. Indeed, we observed a significant increase in CD11b+/CD45hi cells (believed to be monocytes based on their high expression of CD45 [56, 57]) in Tg2576 animals compared to non-Tg controls. We also found that accumulation of CD11b+/CD45hi cells is significantly impaired in Tg2576 mice deficient in the chemokine receptor Ccr2 [8], a major chemokine receptor highly expressed on monocytes [58] but not on resident microglia [16]. This was later confirmed by Naert and colleagues [59]. More recent reports showed that cells expressing monocyte markers are associated with plaques in two transgenic models of Aβ deposition [60], and that adoptively transferred monocytes home in to these plaques [61]. Furthermore, while CD36 is expressed in microglial cells, its level of expression on peripheral monocytes and macrophages is more than 100-fold higher than in microglial cells [16]. These studies raise the possibility that Aβ-induced CD36-dependent inflammasome activation in AD may occur not only in microglia but also in peripheral blood monocytes recruited to the brain.

Conclusions

The NLRP3 inflammasome appears to play an important role in the pathogenesis and progression of AD making an attractive target for therapeutic intervention. However, interfering with keyparts of the inflammasome (NLRP3, ASC and Caspase-1) in a shotgun manner as a therapeutic approach may also have serious systemic effects because of the ubiquitous distribution and importance of inflammasome activation in many peripheral processes. Future research should focus on identifying CNS-specific pathways leading to inflammasome activation, including possible additional receptors or endogenous cell-specific inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

Maike Gold is a postdoctoral Research Fellow of the Max Kade Foundation. Part of the work described here was supported by NIH grants NIH grants NS059005, AG032349 and AI082660 to Joseph El Khoury.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.McGeer PL, et al. Reactive microglia in patients with senile dementia of the Alzheimer type are positive for the histocompatibility glycoprotein HLA-DR. Neurosci Lett. 1987;79(1-2):195–200. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90696-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rozemuller JM, Eikelenboom P, Stam FC. Role of microglia in plaque formation in senile dementia of the Alzheimer type. An immunohistochemical study Virchows. Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol. 1986;51(3):247–54. doi: 10.1007/BF02899034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frautschy SA, et al. Microglial response to amyloid plaques in APPsw transgenic mice. Am J Pathol. 1998;152(1):307–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hickman SE, Allison EK, El Khoury J. Microglial dysfunction and defective beta-amyloid clearance pathways in aging Alzheimer’s disease mice. J Neurosci. 2008;28(33):8354–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0616-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El Khoury J. Neurodegeneration and the neuroimmune system. Nat Med. 2010;16(12):1369–70. doi: 10.1038/nm1210-1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kettenmann H, et al. Physiology of microglia. Physiol Rev. 2011;91(2):461–553. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El Khoury J, Luster AD. Mechanisms of microglia accumulation in Alzheimer’s disease: therapeutic implications. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29(12):626–32. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El Khoury J, et al. Ccr2 deficiency impairs microglial accumulation and accelerates progression of Alzheimer-like disease. Nat Med. 2007;13(4):432–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El Khoury JB, et al. CD36 mediates the innate host response to beta-amyloid. J Exp Med. 2003;197(12):1657–66. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frenkel D, et al. Scara1 deficiency impairs clearance of soluble amyloid-beta by mononuclear phagocytes and accelerates Alzheimer’s-like disease progression. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2030. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stewart CR, et al. CD36 ligands promote sterile inflammation through assembly of a Toll-like receptor 4 and 6 heterodimer. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(2):155–61. doi: 10.1038/ni.1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halle A, et al. The NALP3 inflammasome is involved in the innate immune response to amyloid-beta. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(8):857–65. doi: 10.1038/ni.1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heneka MT, et al. NLRP3 is activated in Alzheimer’s disease and contributes to pathology in APP/PS1 mice. Nature. 2013;493(7434):674–8. doi: 10.1038/nature11729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheedy FJ, et al. CD36 coordinates NLRP3 inflammasome activation by facilitating intracellular nucleation of soluble ligands into particulate ligands in sterile inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2013;14(8):812–20. doi: 10.1038/ni.2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawson LJ, et al. Heterogeneity in the distribution and morphology of microglia in the normal adult mouse brain. Neuroscience. 1990;39(1):151–70. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90229-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hickman SE, et al. The microglial sensome revealed by direct RNA sequencing. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(12):1896–905. doi: 10.1038/nn.3554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stence N, Waite M, Dailey ME. Dynamics of microglial activation: a confocal time-lapse analysis in hippocampal slices. Glia. 2001;33(3):256–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mogi M, et al. Interleukin-1 beta, interleukin-6, epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor-alpha are elevated in the brain from parkinsonian patients. Neurosci Lett. 1994;180(2):147–50. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90508-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morimoto K, et al. Expression profiles of cytokines in the brains of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients compared to the brains of non-demented patients with and without increasing AD pathology. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;25(1):59–76. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-101815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stoeck K, Bodemer M, Zerr I. Pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in the CSF of patients with Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;172(1-2):175–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coraci IS, et al. CD36, a class B scavenger receptor, is expressed on microglia in Alzheimer’s disease brains and can mediate production of reactive oxygen species in response to beta-amyloid fibrils. Am J Pathol. 2002;160(1):101–12. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64354-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cunningham C. Microglia and neurodegeneration: the role of systemic inflammation. Glia. 2013;61(1):71–90. doi: 10.1002/glia.22350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cho S, et al. Repression of proinflammatory cytokine and inducible nitric oxide synthase (NOS2) gene expression in activated microglia by N-acetyl-O-methyldopamine: protein kinase A-dependent mechanism. Glia. 2001;33(4):324–33. doi: 10.1002/1098-1136(20010315)33:4<324::aid-glia1031>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yates SL, et al. Amyloid beta and amylin fibrils induce increases in proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine production by THP-1 cells and murine microglia. J Neurochem. 2000;74(3):1017–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0741017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goodwin JL, Kehrli ME, Jr, Uemura E. Integrin Mac-1 and beta-amyloid in microglial release of nitric oxide. Brain Res. 1997;768(1-2):279–86. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00653-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinon F, Burns K, Tschopp J. The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of proIL-beta. Mol Cell. 2002;10(2):417–26. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boyden ED, Dietrich WF. Nalp1b controls mouse macrophage susceptibility to anthrax lethal toxin. Nat Genet. 2006;38(2):240–4. doi: 10.1038/ng1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mariathasan S, et al. Cryopyrin activates the inflammasome in response to toxins and ATP. Nature. 2006;440(7081):228–32. doi: 10.1038/nature04515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mariathasan S, et al. Differential activation of the inflammasome by caspase-1 adaptors ASC and Ipaf. Nature. 2004;430(6996):213–8. doi: 10.1038/nature02664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rathinam VA, et al. The AIM2 inflammasome is essential for host defense against cytosolic bacteria and DNA viruses. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(5):395–402. doi: 10.1038/ni.1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gross O, et al. Syk kinase signalling couples to the Nlrp3 inflammasome for anti-fungal host defence. Nature. 2009;459(7245):433–6. doi: 10.1038/nature07965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rathinam VA, et al. TRIF licenses caspase-11-dependent NLRP3 inflammasome activation by gram-negative bacteria. Cell. 2012;150(3):606–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martinon F, et al. Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature. 2006;440(7081):237–41. doi: 10.1038/nature04516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duewell P, et al. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature. 2010;464(7293):1357–61. doi: 10.1038/nature08938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garlanda C, Dinarello CA, Mantovani A. The interleukin-1 family: back to the future. Immunity. 2013;39(6):1003–18. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lynch MA. Age-related neuroinflammatory changes negatively impact on neuronal function. Front Aging Neurosci. 2010;1:6. doi: 10.3389/neuro.24.006.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bauernfeind FG, et al. Cutting edge: NF-kappaB activating pattern recognition and cytokine receptors license NLRP3 inflammasome activation by regulating NLRP3 expression. J Immunol. 2009;183(2):787–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Franchi L, Eigenbrod T, Nunez G. Cutting edge: TNF-alpha mediates sensitization to ATP and silica via the NLRP3 inflammasome in the absence of microbial stimulation. J Immunol. 2009;183(2):792–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chow JC, et al. Toll-like receptor-4 mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(16):10689–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Juliana C, et al. Non-transcriptional priming and deubiquitination regulate NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(43):36617–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.407130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duncan JA, et al. Cryopyrin/NALP3 binds ATP/dATP, is an ATPase, and requires ATP binding to mediate inflammatory signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(19):8041–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611496104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Srinivasula SM, et al. The PYRIN-CARD protein ASC is an activating adaptor for caspase-1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(24):21119–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200179200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baroja-Mazo A, et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome is released as a particulate danger signal that amplifies the inflammatory response. Nat Immunol. 2014;15(8):738–48. doi: 10.1038/ni.2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Franklin BS, et al. The adaptor ASC has extracellular and ‘prionoid’ activities that propagate inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2014;15(8):727–37. doi: 10.1038/ni.2913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yan Y, et al. Dopamine Controls Systemic Inflammation through Inhibition of NLRP3 Inflammasome. Cell. 2015;160(1-2):62–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sarkar C, et al. The immunoregulatory role of dopamine: an update. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24(4):525–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee GS, et al. The calcium-sensing receptor regulates the NLRP3 inflammasome through Ca2+ and cAMP. Nature. 2012;492(7427):123–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Coll RC, et al. A small-molecule inhibitor of the NLRP3 inflammasome for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Nat Med. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nm.3806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Griffin WS, et al. Brain interleukin 1 and S-100 immunoreactivity are elevated in Down syndrome and Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86(19):7611–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.19.7611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murphy N, Grehan B, Lynch MA. Glial uptake of amyloid beta induces NLRP3 inflammasome formation via cathepsin-dependent degradation of NLRP10. Neuromolecular Med. 2014;16(1):205–15. doi: 10.1007/s12017-013-8274-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kahlenberg JM, Dubyak GR. Mechanisms of caspase-1 activation by P2X7 receptor-mediated K+ release. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286(5):C1100–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00494.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McLarnon JG, et al. Upregulated expression of purinergic P2X(7) receptor in Alzheimer disease and amyloid-beta peptide-treated microglia and in peptide-injected rat hippocampus. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65(11):1090–7. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000240470.97295.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kahlenberg JM, et al. Potentiation of caspase-1 activation by the P2X7 receptor is dependent on TLR signals and requires NF-kappaB-driven protein synthesis. J Immunol. 2005;175(11):7611–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wegiel J, et al. Origin and turnover of microglial cells in fibrillar plaques of APPsw transgenic mice. Acta Neuropathol. 2003;105(4):393–402. doi: 10.1007/s00401-002-0660-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lebson L, et al. Trafficking CD11b-positive blood cells deliver therapeutic genes to the brain of amyloid-depositing transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2010;30(29):9651–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0329-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bennett JL, et al. CCL2 transgene expression in the central nervous system directs diffuse infiltration of CD45(high)CD11b(+) monocytes and enhanced Theiler’s murine encephalomyelitis virus-induced demyelinating disease. J Neurovirol. 2003;9(6):623–36. doi: 10.1080/13550280390247551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sedgwick JD, et al. Isolation and direct characterization of resident microglial cells from the normal and inflamed central nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(16):7438–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.16.7438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saederup N, et al. Selective chemokine receptor usage by central nervous system myeloid cells in CCR2-red fluorescent protein knock-in mice. PLoS One. 2010;5(10):e13693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Naert G, Rivest S. Hematopoietic CC-chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) competent cells are protective for the cognitive impairments and amyloid pathology in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Med. 2012;18:297–313. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jay TR, et al. TREM2 deficiency eliminates TREM2+ inflammatory macrophages and ameliorates pathology in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. J Exp Med. 2015 doi: 10.1084/jem.20142322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Koronyo Y, et al. Therapeutic effects of glatiramer acetate and grafted CD115+ monocytes in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2015 doi: 10.1093/brain/awv150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]