Abstract

Synthetic nerve conduits represent a promising strategy to enhance functional recovery in peripheral nerve injury repair. However, the efficiency of synthetic nerve conduits is often compromised by the lack of molecular factors to create an enriched microenvironment for nerve regeneration. Here, we investigate the in vivo response of mono (MC) and bi-component (BC) fibrous conduits obtained by processing via electrospinning poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) and gelatin solutions. In vitro studies demonstrate that the inclusion of gelatin leads to uniform electrospun fiber size and positively influences the response of Dorsal Root Ganglia (DRGs) neurons as confirmed by the preferential extensions of neurites from DRG bodies. This behavior can be attributed to gelatin as a bioactive cue for the cultured DRG and to the reduced fibers size. However, in vivo studies in rat sciatic nerve defect model show an opposite response: MC conduits stimulate superior nerve regeneration than gelatin containing PCL conduits as confirmed by electrophysiology, muscle weight and histology. The G-ratio, 0.71 ± 0.07 for MC and 0.66 ± 0.05 for autograft, is close to 0.6, the value measured in healthy nerves. In contrast, BC implants elicited a strong host response and infiltrating tissue occluded the conduits preventing the formation of myelinated axons.

Therefore, although gelatin promotes in vitro nerve regeneration, we conclude that bi-component electrospun conduits are not satisfactory in vivo due to intrinsic limits to their mechanical performance and degradation kinetics, which are essential to peripheral nerve regeneration in vivo.

Keywords: Electrospinning, In vivo model, Tubular conduit, Sciatic nerve regeneration

1. Introduction

Peripheral nerve injuries are very common in clinical practice and often lead to permanent disability. Once the adult nerve tissue is injured, regeneration is often sub-optimal and poor recovery correlates with increasing gap length of the injury [1–3]. Currently, nerve autografts are considered as the “gold standard” for the structural and functional restoration of nerves. However several drawbacks are related to the use of autografts, including secondary surgery, donor site morbidity, limited availability, size mismatch and painful neuroma formation.

Nerve conduits represent a promising alternative for the regeneration of damaged or transected peripheral nerves. In this context, conduits can act as a bridge, providing directional guidance as well as biological support to nerve regeneration [4]. In ensuring the success of neural tissue engineering strategies, material choice plays a crucial role as demonstrated by Ezra et al. [5]. By tailoring the material degradation rates and mechanical properties it is possible to minimize the inflammatory response, thus improving the support and guidance to sustain axon regeneration [6].

A large body of research has been conducted to investigate different kinds of biomaterials for neural tissue engineering including, synthetic materials such as poly(glycolic acid) (PGA) [7], poly(l-lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) [8,9], poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (PHB) [10,11] and natural biopolymers such as gelatin [12–14], collagen [3,8,15–19], chitosan [7,20–23] and silk [24,25]. Synthetic materials are attractive as neural tissue engineering scaffolds because of the ease in tailoring the degradation rate and mechanical properties of these materials to suit the application. On the other hand, natural polymers, such as collagen and gelatin, offer biomolecular recognition sites [26] but must be stabilized by cross-linking or other methods in order to yield a stable nerve conduit material that can maintain its integrity during the regenerative period.

A considerable effort has been dedicated developing synthetic nerve conduits to bridge long nerve gaps. However, more work needs to be done to improve their efficacy compared to autologous nerve grafts and several designs of nerve conduits have been proposed.

Recently, alternative repair strategies include the use of intraluminal guidance structures and micro-grooved luminal designs [27] to provide additional structure support and topographical guidance to regenerating axons and migrating Schwann cells (SC). However, the presence of fillers clustered in the center of the conduit may reduce axonal regeneration leading to regeneration failure [28]. The addition of a dense collagen sponge within a hollow nerve conduit completely inhibits regeneration [29]. These results illustrate the importance of correct placement of intraluminal fillers within a hollow nerve conduit and the proper choice of materials.

Given the unmet need, investigating new biomaterials that can better interact with cells remains an area of intense research [25]. Equally important is the development of inexpensive processing methods that can create the fine structures necessary to support the regenerative niche. Processing techniques must allow for maintaining fine control of their structural properties, at micro- and nano-meter level, to present to cells topographical cues matching their native environment during the regeneration process [30].

Flemming et al. demonstrated that purely topographical cues offered by nanofibers mimic the conformation of the extracellular matrix thus supporting cell response (i.e., adhesion, the ability of cells to orient themselves, migrate and produce organized cyto-skeletal arrangements) [31]. Similar studies on nerve regeneration revealed that in addition to fiber architecture, the combined contribution of biochemical cues can further support the main cellular events triggering cell adhesion and neurite outgrowth over the fiber scaffold [32,33]. Electrospinning represents a promising strategy to produce fibrous conduits able to assure high porosity and large surface areas for cell attachment and nutrient transportation. Furthermore, the chance to process by electrospinning mixtures of synthetic and natural polymers can guarantee the interactions with cultured cells while having suitable mechanical properties and degradation rate to provide longitudinal support for the regenerating nerves [33–35].

Our paper focuses on the production of mono-component (MC) and bi-component (BC) conduits made of PCL and PCL/gelatin by electrospinning. MC and BC tubular conduits have been fabricated with tunable three-dimensional (3D) microarchitecture by electric force driven deposition of fibers onto a rotating mandrel. Previous investigations have demonstrated the biocompatibility of similar fibers in in vitro conditions [33–35]. Here we confirm the ability to provide a favorable environment that supports the growth of cells in vitro. Moreover, we investigate the response in vivo of PCL and PCL/gelatin conduits to stimulate nerve regeneration in rat sciatic nerve defects.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

PCL pellets (Mn 45 kDa) and gelatin of type B (~225 Bloom) from bovine skin in powder form, were all purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (Italy), while 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFP) was supplied by Fluka (Italy) and chloroform (CHCl3) by J.T. Baker (Italy). All products were used as received without further purification.

A 1:1 (weight ratio) polymer solution of PCL and gelatin was prepared by first dissolving the polymers separately in HFP for 24 h under magnetic stirring and then mixing them in order to obtain a solution with a final polymer concentration of 0.1 g/ml.

PCL alone was dissolved in chloroform at a concentration of 0.33 g/ml. The mixture was kept under magnetic stirring at room temperature until a clear solution was obtained.

2.2. Preparation of the electrospun conduits

Electrospun fiber membranes were obtained by using a commercially available electrospinning setup (Nanon01, MECC, Japan). The polymer solution was placed in a 5 ml plastic syringe connected to an 18 Gauge needle. At the first stage, fibers were randomly collected over a grounded aluminium foil target in order to obtain flat membranes. Different process parameters were selected to optimize the final fiber morphology: in particular, optimal BC fiber membranes were fabricated by setting a distance of 8 cm, a voltage of 13 kV and a flow rate of 0.5 ml/h while MC fiber membranes were fabricated by adjusting the parameters to 15 cm, 20 kV, 0.5 ml/h respectively. The process was carried out in a vertical configuration at 25 °C and 50% relative humidity, and the deposition time was adequate to obtain the proper thickness (~150 μm) to remove the membranes from the grid. MC and BC conduits (thickness 1 mm) were developed by collecting fibers onto a 1.5 mm diameter metal mandrel, with a rotating rate of 50 rpm.

Flat membranes were cut into 6 mm discs and placed into 96-well tissue culture plates for biological characterization. Prior to the biological assays, MC and BC fiber sheets and conduits were sterilized by immersion in 70% of ethanol (v/v) with antibiotic solution (100 μg/ml streptomycin and 100 U/ml penicillin) for 30 min, washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and air dried.

2.3. Morphological characterization

Qualitative evaluation of fiber morphology of the electrospun MC and BC membranes and conduits was performed by field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, QUANTA200, FEI, The Netherlands). Samples were dried in the fume hood for 24 h in order to remove any residual solvent, mounted on metal stubs and sputter-coated with gold–palladium for about 20 s in order to get a 19 nm thick conductive layer. SEM images were taken under high vacuum conditions (10−7torr) at 10 kV, using the secondary electron detector (SED). On selected SEM images, the fiber diameter distribution, the mean total porous area and the % porosity were determined by using image analysis freeware (NIH ImageJ 1.37).

2.4. Mechanical flattening tests

Transverse compression testing of MC and BC conduits was performed using a dynamometric machine (Instron 5566). The length of samples (n = 5/group) was 7 mm and the tube wall thickness was measured before testing. All the tubes were hydrated before testing by soaking them in deionized water for 10 min. The cross-head speed was maintained at 1 mm/min and the cell load was 100 N. The compressive strengths of MC and BC tubes were reported against the displacement values, calculated as the ratio between the outer diameter of the flattened tube and the initial outer diameter. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation on five different samples (n = 5).

2.5. In vitro response of dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons

All sterilized samples were immersed in Dulbecco's Modified Essential Medium (DMEM) for 24 h prior to plating undissociated lumbar DRGs dissected from E15 chick embryos and then cultured in DMEM, supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, antibiotic solution (streptomycin, 100 μg/ml, and penicillin, 100 U/mL), 2 mm l-glutamine and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 and 95% air. After 24 and 72 h of seeding, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Individual neurites extending from the DRG were visualized by staining with NF-200 antibody and fluorescence microscopy. Neurite length was quantified using ImageJ software from randomly selected high magnification images of neurites extending from the DRG periphery. All experiments were run in triplicate.

2.6. In vivo implants

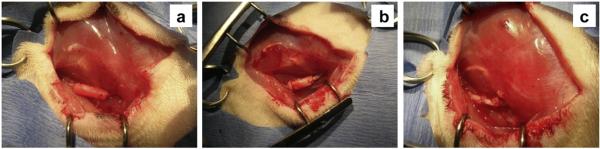

Eighteen female Lewis rats weighing 225–250 g were used for this study. Procedures were reviewed and approved by the Rutgers University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Rats were randomly assigned to one of three groups (n = 6 rats/group). As described elsewhere [36], an incision was made along the left femoral axis on the left leg posterior to the femur. A 5 mm nerve segment was resected 5 mm distal to the internal obturator tendon. 7 mm long nerve conduits were secured to nerve stumps with two 9-0 ethilon sutures (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) on either side, leaving a 5 mm gap between the stumps (Fig. 1a–b). In the autologous graft group, a 5 mm nerve segment was resected, reversed 180° and subsequently sutured back into the nerve using four 9-0 ethilon sutures on either side (Fig. 1c). Muscle and skin were then closed with 6-0 ethilon sutures. Rats were given on oral acetaminophen for 7 days post-op along with an E-collar (if warranted) to prevent autophagia/autotomy.

Fig. 1.

Appearance of conduits and autologous graft at the sciatic nerve transection site: a) MC; b) BC and c) autologous graft.

2.7. Electrophysiological recordings

Compound muscle action potentials (CMAPs) were recorded using an electromyography (EMG) system (Viking Quest, CareFusion, San Diego, CA). All rats were anesthetized and microelectrodes were placed in the appropriate foot musculature following three different approaches. A distal recording (DR) of signals was obtained placing the ground electrode at the Achilles tendon, the reference electrode at the lateral side of the fifth digit of the foot and the recording electrode at the plantar or dorsal side of the foot for the tibial or peroneal nerve, respectively, while applying a supramaximal stimulus, using bipolar electrodes placed 4 mm apart, just posterior of the tibia, distal to the injury site (distal stimulation, DS). Further distal recordings were taken with supramaximal stimulus applied proximal to the injury site (proximal stimulation, PS). Potentials were also recorded proximally to the injury site (proximal recording, PR) by placing the recording electrodes directly into tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius muscles, respectively innervated by peroneal and tibial nerve branches, while applying supramaximal stimulus proximal to the injury site. CMAPs were recorded prior to surgery and at day10, wk4, wk8, wk12 and wk18 postoperatively. The electrophysiological response was characterized by calculating the peak amplitude and latency and reported in three combinations: proximal stimulation- proximal recording (PS-PR), proximal stimulation- distal recording (PS-DR), distal stimulation- distal recording (DS-DR).

2.8. Nerve histology and muscle weight

After 18 weeks, rats were deeply anesthetized using ketamine/xylazine anesthesia and a final EMG measurement was taken. The implant site was exposed and in-situ fixation of the nerve was performed by flooding the muscle pocket in Trump's fixative (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) for 30 min. The nerve was then transected and further fixed in Trump's buffer for 5 days, post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, and embedded in epoxy resin. The mid tube segment of the nerve was transversely cut into 1 μm thick sections and stained with a solution of 1% toluidine blue/1% borax in distilled water. Images of sections were acquired using a camera connected to a microscope at a magnification of 20× and 100×. For each type of implant, 9 random images selected for quantification at 100× magnification. Images were used to calculate the total fiber diameter, axonal diameter and G-ratio. After nerve harvest, animals were immediately sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation and the tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius muscles of both hind legs were harvested and weighed to assess the recovery of the muscle weight after nerve regeneration and reinnervation.

3. Results

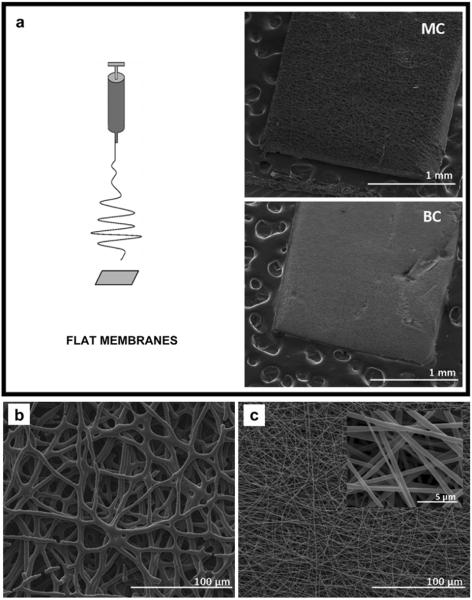

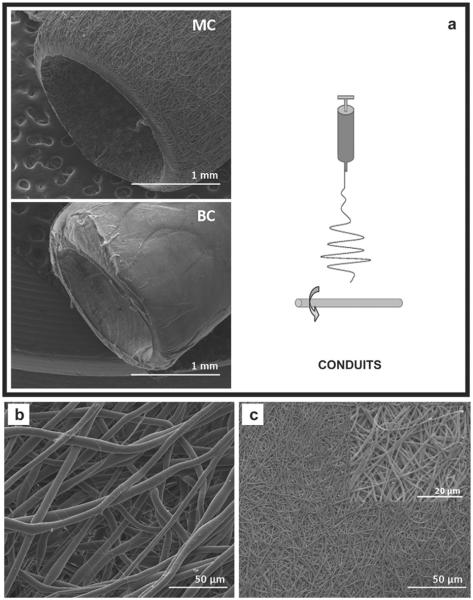

In this study, MC and BC fibrous membranes were fabricated by electrospinning to explore their application as nerve guidance substrates in vitro and in vivo. A flat aluminum target and a rotating mandrel were used to produce flat fibrous membranes and conduits, respectively (Figs. 2a and 3a). MC membranes were composed of microfibers with average diameter of (5.61 ± 0.8) μm (Fig. 2b). BC fibers (Fig. 2c) fell in the sub-micron range with an average diameter of (0.59 ± 0.15) μm. Fig. 3b and c show SEM images of MC and BC fibers along the surface of the electrospun conduit. SEM images confirm that the use of rotating collectors does not influence fiber morphology moving from 2D (membranes) to 3D (tubular) shapes.

Fig. 2.

a) Electrospinning setup for flat membrane production and the low magnification SEM images of MC (top) and BC (bottom) flat sheets; b) Higher magnification SEM images of mono-component (MC) and (c) and bi-component (BC) flat sheets.

Fig. 3.

a) Electrospinning setup for conduit production and the low magnification SEM images of MC (top) and BC (bottom) conduits; b) Higher magnification SEM images of mono-component (MC) and (c) and bi-component (BC) conduits.

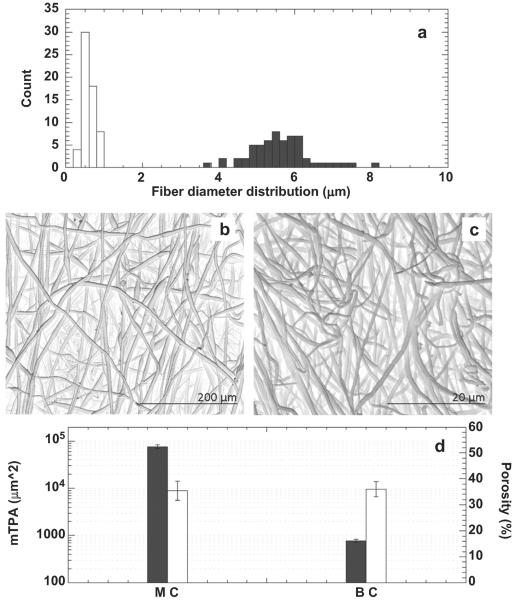

The distribution of fiber diameter was assessed by using image analysis as shown in Fig. 4a. BC fibers were shown to have a narrower diameter distribution in comparison to MC, by statistical modes of 0.70 μm and 4.75 μm and skewness of 0.26 and 0.40 for BC and MC fibers, respectively. Mesh porosity (%) and the mean total pore area (μm2), plotted in Fig. 4d were calculated by using an inverse contrast tool on SEM images (Fig. 4b–c). Porosity was comparable in the case of MC (35.47 ± 3.66%) and BC (36.05 ± 2.86%) electrospun conduits, but the mean porous area was much greater for MC (76.6 ± 7.8) × 103 μm2 as compared to BC fiber conduits (7.8 ± 0.6) × 102 μm2.

Fig. 4.

Image analysis data of selected images: a) fiber diameters distribution for fiber mats (MC, ■) and (BC, □); inverse contrast SEM images of PCL(b) and PCL/gel (c) samples; d) Mean total porous area (mTPA, ■) and porosity (□).

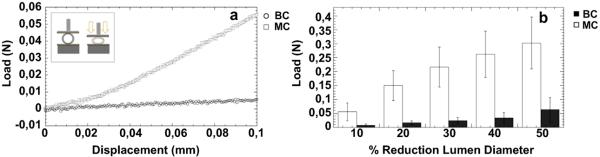

The transverse compressive strengths of electrospun tubes were measured by applying a transverse displacement to the longitudinal axis (Fig. 5a) and analyzing the resulting load. Comparative analysis of the load-displacement curves, in Fig. 5b, shows that BC conduits possessed lower load-bearing ability and compressive strength than MC tubes for displacement values up to 50%. In particular, for a load of 0.05 N, the reduction of lumen diameter about 10% for MC and 50% for BC is recorded. This difference is amplified for low displacement (<0.1 mm) as reported in Fig. 5a.

Fig. 5.

Transverse compressive tests on MC and BC conduits: a) load–displacement curve for small displacement (<0.1 mm); b) comparative histogram showing the loads necessary to obtain up to 50% reduction in lumen diameter.

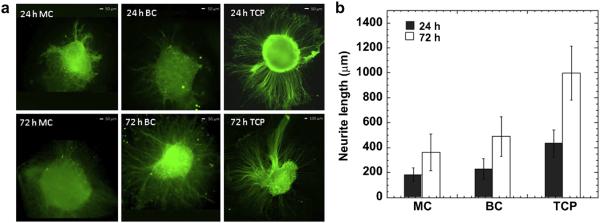

We next assessed the cytocompatibility of MC and BC fibers in vitro using dorsal root ganglia (DRG) isolated from chick embryos. DRGs were seeded on the electrospun fiber membranes and on tissue culture plates (TCP) coated with laminin. DRGs were fixed after 24 h and 72 h in culture and neurite extension was evaluated using fluorescence microscopy. After 24 h, DRGs adhered on all the examined samples, but neurite extension out from the DRG was greater on BC fiber membranes and TCP controls (CTR) than on MC fiber membranes (Fig. 6). After 72 h, neurites appeared to have extended along the fiber axes outward from the main DRG body without any directional preference, therefore exhibiting a circular appearance. Neurites appeared to have preferentially grown along the BC fibers and laminin-coated TCP and less along MC fibers. Thus, it appears that the inclusion of the gelatin with the PCL in the fiber membranes enhanced DRG adhesion and neurite extension compared to the MC fiber membranes.

Fig. 6.

Biological validation in vitro: a) DRG's confocal images after seeding 24 h and 72 h on MC, BC fibers and on the CTR; b) average neurite length at 24 h and 72 h of seeding.

Next, the in vivo efficacy of electrospun nerve conduits was next evaluated in the 5 mm rat sciatic nerve defect model. MC and BC conduits were implanted to repair a 5 mm defect and the results were compared to a 5 mm autograft repair control group. Recovery was assessed using muscle weight measurements, histology of the regenerated nerve and electrophysiology to determine the ability of regenerated nerve to conduct electric impulses to target muscles.

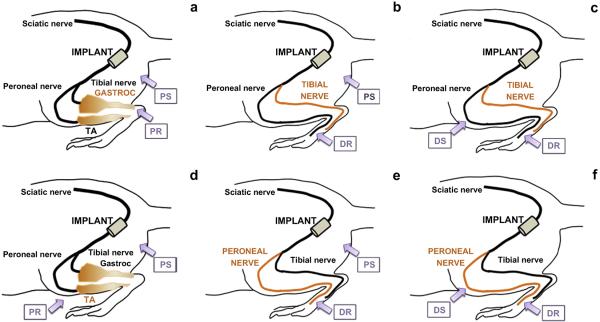

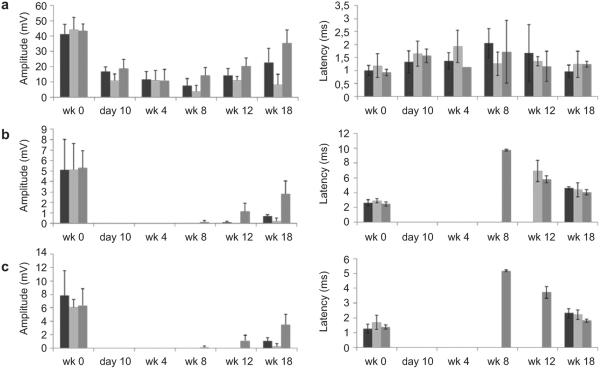

CMAPs were recorded for the peroneal and tibial branches of the sciatic nerve. For each branch, CMAPs were measured from two separate stimulation sites and two recording sites (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Tibial compound muscle action potential (CMAP) measured by placing the electrodes in three different anatomical locations: a) Proximal stimulation (PS) – proximal recording (PR); b) Proximal stimulation (PS) – distal recording (DR); c) Distal stimulation (DS) – distal recording (DR). Peroneal CMAP measured by placing the electrodes in three different anatomical locations: d) Proximal stimulation (PS) – proximal recording (PR); e) Proximal stimulation (PS) – distal recording (DR); f) Distal stimulation (DS) – distal recording (DR).

By stimulating and recording at two different locations for each branch, it is possible to gain a more complete assessment of nerve conduction. Proximal stimulation (PS) was applied proximal to the branching point of the sciatic nerve and distal stimulation (DS) was applied distal to the branching point but along the peroneal or tibial branches wrapping around the ankle. Recordings were likewise taken at two different locations for each branch of the sciatic nerve, with notations of proximal recording (PR) and distal recording (DR). For the peroneal nerve, the DR was measured with the recording electrode inserted into the dorsal side of the foot, and the PR was measured by inserting the recording electrode at the center of the tibialis anterior muscle. In the case of the tibial nerve, DR was measured from the plantar side of the foot and PR from the center of the gastrocnemius muscle. We observed high background signal from PS-PR for both branches even in the absence of nerve regeneration (10 days after surgery), likely due to the close proximity of the recording and stimulating electrodes.

Electrophysiological recordings of the tibial and peroneal branches of the sciatic nerve indicated that MC conduits promoted superior regeneration compared to BC conduits (Figs. 8 and 9). Both PS-DR and DS-DR measurements show that signal amplitude trended higher for MC conduits compared with BC conduits. Significant differences in latency weren't observed among groups however the autograft group had shorter latencies in PS-DR and DS-DR modes, in correlation with the higher autograft amplitudes in these modes. Autograft was superior to both conduit groups and signals could be found earlier in the regenerative period (8 weeks compared to 12 or 18 weeks for the conduits).

Fig. 8.

Electrophysiological recordings from the in vivo study. Tibial CMAP amplitude and latency, measured by placing the EMG electrodes in three different anatomical locations: a) Proximal stimulation (PS) – proximal recording (PR); b) Proximal stimulation (PS) – distal recording (DR); c) Distal stimulation (DS) – distal recording (DR) [autograft, n = 4 ( ); MC, n = 5 (■) and BC, n = 6 (

); MC, n = 5 (■) and BC, n = 6 ( )].

)].

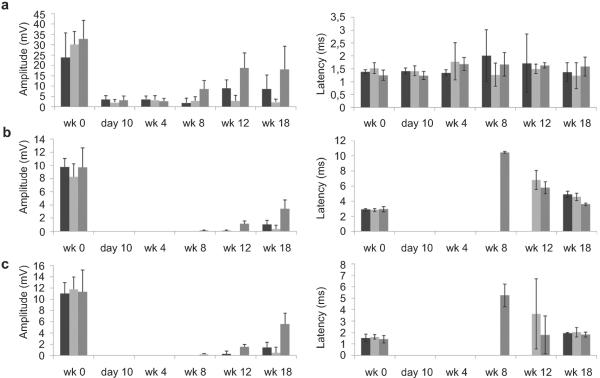

Fig. 9.

Electrophysiological recordings from the in vivo study. Peroneal CMAP amplitude and latency, measured by placing the EMG electrodes in three different anatomical locations: a) Proximal stimulation (PS) - proximal recording (PR); b) Proximal stimulation (PS) - distal recording (DR); c) Distal stimulation (DS) - distal recording (DR) [autograft, n = 4 (■); MC, n = 5 ( ) and BC, n = 6 (

) and BC, n = 6 ( )].

)].

At the end of the 18-week regenerative period signal latency had returned close to pre-injury levels for responding animals but this was not the case for the signal amplitude, which remained much lower than pre-injury levels. The percentage of the amplitude at the endpoint with respect to the healthy levels for each group was calculated as the percent recovery of the CMAP amplitude and reported in Table 1 for both tibial and peroneal nerve. The autograft group showed the best electrophysiological recovery; regaining 53–83% (tibial nerve) and 35–55% (peroneal nerve) of the baseline amplitude measured prior to injury. Recovery of CMAP amplitude was significantly greater in MC conduits compared to BC conduits in all recording modes for both tibial and peroneal nerve. Together, this likely indicates the regeneration of mature and well myelinated axons capable of rapidly conducting signals but that overall fewer of these axons regenerated in the MC group compared to the autograft group. Also when the number of responsive animals was taken into account, all the animals in the MC and autograft groups were responsive with positive CMAP amplitude, which was markedly better than the BC group with only 2 out of 6 animals that had a positive CMAP signal (4 out of 6 animals non-responsive) by 18 weeks.

Table 1.

Percent recovery of the CMAP amplitude for MC, BC and autografts measured at the study endpoint for tibial and peroneal nerve.

| Autograft | MC | BC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tibial nerve | PS-PR | 83 | 55 | 19 |

| PS-DR | 53 | 14 | 4 | |

| DS-DR | 55 | 14 | 4 | |

| Peroneal nerve | PS-PR | 55 | 36 | 8 |

| PS-DR | 35 | 10 | 4 | |

| DS-DR | 49 | 13 | 4 |

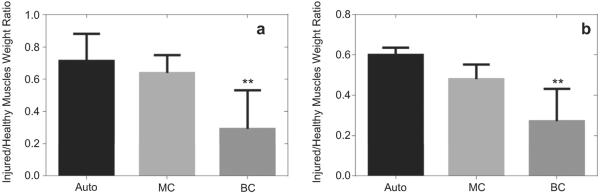

Tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius muscle weights were also measured at sacrifice. This serves as an additional metric of nerve regeneration as muscles rapidly atrophy after loss of motor impulses and will regain mass as the nerve functionally reinnervates the muscle [37]. The ratios of injured muscle weight to the healthy muscle weight were plotted in Fig. 10. The autograft group had the highest degree of muscle weight recovery followed by the MC group (Fig. 10). The animals with BC implants had the lowest muscle weight recovery, with both muscle groups still bearing significant atrophy after 18 weeks of conduit repair.

Fig. 10.

The ratio of the injured muscle weight to the healthy muscle weight in the tibialis anterior (a) and gastrocnemius muscles (b) 18 weeks post-op. [autograft, n = 4 (■); MC, n = 5 ( ) and BC, n = 6 (

) and BC, n = 6 ( )]. Asterisk denotes significant differences (p < 0.01) from BC conduits as compared to MC and autograft as determined by one-way ANOVA test.

)]. Asterisk denotes significant differences (p < 0.01) from BC conduits as compared to MC and autograft as determined by one-way ANOVA test.

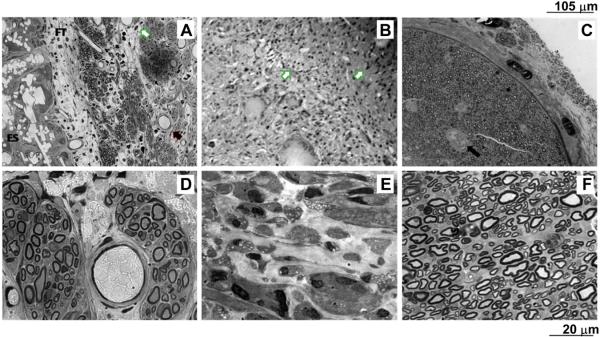

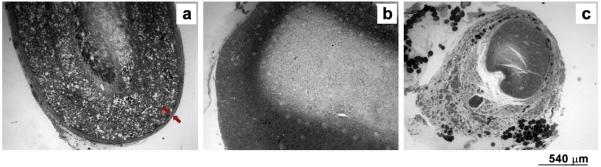

Histological and histomorphometric analyses were performed to compare the morphology of the regenerated axons and the surrounding myelin sheet. Representative images of 1 μm thick toluidine-blue stained nerve mid-sections are shown in Fig. 11. Rats implanted with MC or autografts had robust nerve cables, while only a few myelinated axons and more inflammatory cells were present in BC implants. The lumen of MC tubes was also co-occupied with fibrous and connective tissue enclosing the axons and blood vessels (Fig. 11A), with the myelinated axons evident at higher magnification images (Fig. 11D). On the other hand, BC conduits induced a strong inflammatory response and excessive fibrous tissue infiltration without any clear axonal regeneration, (Fig. 11B–E). Histology confirmed that autologous nerve promoted superior regeneration (Fig. 11C–F).

Fig. 11.

Images of 1 μm thick toluidine-blue stained nerve mid-sections of A) MC; B) BC; C) Autologous graft at low magnification (20×);D) MC; E) BC; F) Autologous graft at high magnification (100×). White arrows point out the presence of inflammatory cells; black arrows signal the presence of blood vessels; FT indicates a fibrous layer that encloses axons; ES states the electrospun conduit.

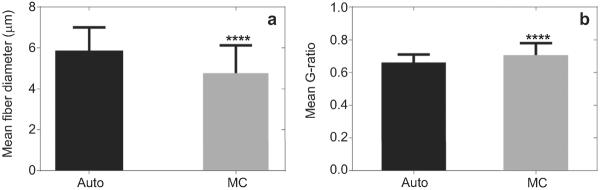

The mean G-ratio for MC and autograft was 0.71 ± 0.07 and 0.66 ± 0.05, respectively (Fig. 12). G-ratio could not be calculated in BC conduits due to the poor axonal regeneration and high degree of inflammation in this group. The mean myelinated fiber diameter was (4.77 ± 1.36) μm for nerve regenerated into MC implant and (5.82 ± 1.18) μm for autograft group.

Fig. 12.

Image analysis data: mean value of G-ratio (a) and mean value of myelinated fiber diameters (b) for all examined samples. Asterisk denotes significant differences (p < 0.0001) from MC implant as compared to Auto as determined by Student's t-test.

A fibrous capsule layer, with a mean thickness of (71.53 ± 28.43) μm, was formed on the outer surface of all MC conduits (Fig. 13a, red arrows), while this layer was absent in the case of autografts and bi-component conduit implants (Fig. 12b–c).

Fig. 13.

Images at low magnification (4×) of 1 μm thick toluidine-blue stained nerve mid-sections of a) MC, red arrows indicate fibrous capsule layer; b) BC and c) autograft, absence of fibrous capsule. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

4. Discussion

Surgical treatments for peripheral nerve injury are less than satisfactory. Although the gold standard of treatment is still the autologous nerve grafting, the development of engineered nerve conduits is progressively emerging as a powerful strategy in the field of peripheral nerve surgery [38,39]. Nondegradable tubes can provide an isolated and stable environment for nerves to regenerate across the gap and toward the distal stump. However, they may also block the nutrient and metabolic exchange between the lumen and the outside environment and cause chronic inflammation and pain due to nerve compression with long-term implants [27,40]. Otherwise, biodegradable implants are able to act as structural support for axons while evoking minimal immune response due to inert release products [41]. However, degradation and resorption profiles of most polymers must be tailored to match the regeneration rate of different peripheral nerves. Among biodegradable systems with different texture and morphological properties, PCL conduits may provide support for axonal regeneration over longer distances, supporting nerve regeneration for many months as demonstrated by Reidl et al. [42]. However, different features from chemical to morphological aspects must be still investigated to recreate the cellular and molecular `regenerative milieu' of an autologous nerve graft within a biomaterial nerve conduit.

In this work, we studied PCL conduits made by electrospinning as a favorable nerve conduit material to support regeneration for many months until nerve is repaired. In comparison with conduits obtained by solvent casting, electrospinning gives rise to totally interconnected porous structures by collecting fibers on cylindrical rotating substrates. The presence of nerve conduit porosity is crucial for the clinical fate of the implant. Here, the mean total porous area of MC tubes is high, this particular feature guarantees the enhancement of nerve growth relative to a nonporous one, since increased porosity leads to enhanced oxygenation of the axons and the exchange of nutrients between the lumen and the outer environment help nerve growth especially in the absence of the distal nerve stump [43,44]. A solid or nonporous conduit may prevent the diffusion of nutrients into the lumen while retaining undesirable waste products, however when the conduit is too porous, nerve regeneration will be reduced due to the infiltration of fibroblasts into the lumen of the conduit [45].

Neverthless, PCL's highly stable and hydrophobic nature often limits its use for biological applications [46]. For instance, Schwann cells (SC) may adhere and proliferate on PCL films but cell response is not generally strong due to the hydrophobicity and lack of polar groups [47]. Hence, the introduction of functional groups onto its surfaces for an enhanced cellular response has previously been achieved using aminolysis [48], plasma treatment [49], or a simple adsorption process [50]. However, such modification processes involving severe chemical reactions might destroy the polymer surface or result in an exchange or removal of the bioactive groups during in vitro culture or in vivo implantation [51]. Mixing PCL with proteins, such as collagen, which is the main component of native ECM can improve the cell responses significantly [33,34] and compensate the major shortcomings of PCL alone. Yu et al. produced electrospun PCL/collagen conduits from fluorinated solutions as graft for peripheral nerve repair and demonstrated that they could support favorable nerve regeneration [52], since the use of collagen implants alone often requires additional chemical treatments of cross-linking to decrease its degradation rate for long-term in vivo use [53–55].

Unfortunately, collagen as an animal-derived biomaterial raises concerns regarding its potential to evoke immune response. Its ability to interact with secreted antibodies, its antigenicity, and tendency to induce an immune response-process that includes synthesis of antibodies are connected with macromolecular features of proteins uncommon to the host species, such as collagens of animal origin.

Zeugolis et al. demonstrated that the interaction of collagen with fluoroalcohols and with strong electric fields denatures collagen to gelatin, leading to the loss of up to 99% of the triple-helical collagen [56]. Unlike collagen, gelatin is a low cost product and its non-antigenicity has attracted great attention. Researchers carried out extensive investigations and the failure of gelatin to incite antibody production has been interpreted in several ways, but the view most commonly held suggests that the nonantigenicity is due to the absence of aromatic groups, as gelatin is deficient in tyrosine and tryptophan, and contains only a very small amount of phenylalanine [57,58]. Given these properties of gelatin, we have recently demonstrated that electrospun fibers induced more efficient mechanisms - i.e., adhesion, proliferation and viability - of rat pheochromocytoma PC-12 cells in the scaffolds where gelatin was added to PCL [33].

In our current work, we developed bi-component electrospun conduits made of PCL directly mixed with gelatin, in order to investigate the complex mechanisms involved in neurons regeneration. In addition to in vitro evaluation of the interaction between conduits materials and primary cells, we compared the in vivo response of MC and BC conduits implanted in a 5 mm rat sciatic nerve defect for 18 weeks. In vitro, BC fibers promoted better neurite outgrowth from DRGs principal body, confirming that the presence of bioactive cues like gelatin in the fibers evidently supports cell attachment and neurite extension by introducing integrin binding sites and hydrophilic amine and carboxylic functional groups. In our previous work [33], we proved that the increased hydrophilicity of BC fibers favors cell adhesion mechanisms compared to MC fibers. Results are confirmed by several studies which showed that PCL/gelatin fibers promoted C17.2 (neonatal mouse cerebellum stem cell line) [59] and U373 (Human glioblastoma-astrocytoma, epithelial-like cell line) proliferation and differentiation [60,61].

In our case, gelatin acts to stabilize the morphology of electrospun fibers preventing the formation of defects and improving the interaction of the polymer solution with the electric field forces, thus promoting the formation of sub-micron fibers [62,63]. In this context, this effect is also enhanced by the use of high permittivity solvents and lower polymer concentration, which together act to increase the pulling force on the jet segment stretching under the effect of the constant Coulomb force, thus reducing the characteristic size of BC fibers down an order of magnitude with respect to MC fibers. These results are in agreement with recent studies on the narrow distribution of fiber diameters in electrospun fibers obtained from solutions with higher dielectric properties [63,64].

Smaller fiber size corresponds to higher surface/volume ratio, which promotes a selective take-up of proteins relevant for cell attachment, such as fibronectin and vitronectin [65]. Moreover, fiber texturing at the nanometric size scale may allow for better exposure of protein for cell activities [66] thus explaining the better in vitro response of cells to BC substrates. Significantly smaller fiber size scale of BC conduits in comparison with MC conduits also leads to smaller pore size, which may be desirable for optimal nerve regeneration [45] although during the in vivo implant period, the mesh porosity in BC conduits was expected to increase gradually due to the gelatin depletion from the fibers, increasing the permeability of conduits while lowering their mechanical strength.

When the BC and MC conduits were tested in vivo to evaluate the role of fiber properties on the success of the implant, our findings were in disagreement to our initial hypothesis that addition of gelatin to PCL would enhance the in vivo nerve regeneration outcomes owing to the presence of bioactive cues and increased surface area for cell attachment. Histological analysis of explanted nerve samples showed numerous myelinated axons and vasculature in the MC conduit group embedded in fibrous tissue occupying the inner lumen of conduits. Strikingly, the lumen of the BC conduits was completely occluded by fibrous tissue and inflammatory cells with no evidence of myelinated axons in this group, thus making impossible the quantification of axon diameter and G-ratio. The BC conduits appear to have lead to excessive fibrous tissue infiltration, which may be due to i) walls that may have become too leaky, ii) gelatin degradation that may have invited increased inflammatory cell attachment or iii) mechanical collapse of the entire conduit structure due to initial weak compressive strength and further compromise of mechanical integrity after implantation.

The conduit material selection is suggested to play a dominant role in modulating cell and nutrient diffusion into conduits where nutrient diffusion through conduit walls is not critical [5,67]. Increased interactions with surface proteins due to the presence of gelatin may outweigh the benefits of having smaller pore size and increased surface area on these conduits and inviting overwhelming degree of fibrous infiltration before the nerve regeneration occurs.

Additionally, we suggest that the occurrence of a significant inflammatory response in the BC group may be due to degradation mechanisms in vivo. Degradation of collagenous linkages requires water and enzyme penetration in vitro, while in vivo degradation is more complex. In vivo, implants are infiltrated by various inflammatory cells, e.g. fibroblasts, macrophages or neutrophils, which cause contraction of the implant and secretion collagen-degrading enzymes, activators, inhibitors, and regulatory molecules, which, in our case may have overcome the regenerative response in BC conduits.

Finally, the mechanical mismatch of the implant with the surrounding tissues in the case of BC conduits may also have contributed to a chronic inflammation with disintegration of conduits and excessive tissue infiltration inside their lumen. It is recognized that the addition of fast–degrading phases of gelatin affects the mechanical integrity of PCL conduits, thus leading to lower load bearing ability [59]. BC conduits, which had significantly lower initial compressive stiffness than MC conduits, appear less suitable for withstanding the stresses during the implantation period and may have failed upon faster degradation and loss of mechanical integrity.

To assess axonal outgrowth and muscle reinnervation, several experimental analyses, including electrophysiology and muscle weight measurements, have been chosen. For electrophysiological assessment, the amplitude of CMAP is a commonly used parameter, which is an indirect measure of the number of regenerated motor nerve fibers and the extent of muscle reinnervation, while latency is an indirect parameter, which refers to maturation of nerve fibers [68]. Electrophysiological assessment of functional recovery recorded as CMAP amplitude and latency indicate superiority of MC conduits over BC conduits to support nerve regeneration after 18 weeks of implantation in vivo as corroborated by histological analysis which showed myelinated axons and vasculature preferentially in MC nerve conduits. The axons in the autologous group are more mature and the G-ratio closer to the theoretical value of 0.6, optimal for the spread of current from one node of Ranvier to the next, observed in most healthy nerves [69]. In the conduit groups, a greater number of myelinated axons is evident in MC implants, which produce a higher CMAP amplitude with respect to BC implants, where the formation of fibrous tissue and inflammatory cells rather than myelinated axons is prevalent, thus making impossible the quantification of axon diameter and G-ratio. These results were also confirmed by the weight ratio of injured muscles to healthy muscles; after 18 weeks the TA and Gastrocnemius muscles were almost entirely atrophied in the case of BC conduits, while those in the MC conduit group had regained much of their original mass. The maintenance of muscle mass is controlled by a balance between protein synthesis and protein degradation pathways. When a muscle is denervated as a result of nerve injury the shift to degradation tendency leads to decreased muscle cell size, muscle weight loss and hyperplasia of connective tissues [70]. As the nerve regenerates into the muscle, it regains its mass proportional to the amount of reinnervation. The significant muscle weight loss in BC conduits therefore indicates failure of BC conduits to support nerve regeneration.

5. Conclusion

Electrospun fibrous conduits show remarkable features for use in tissue engineering strategies for neural tissue repair. The present study indicates that MC conduits are a better choice for in vivo implantation than BC conduits, which yielded consistently poor histology, electrophysiology and muscle weight data. Despite the sub-micron size scale of fibers and their high in vitro recognition by primary nerve cells promoted by chemical and morphological cues, BC electrospun conduits failed to support peripheral nerve regeneration in vivo. In perspective, it will likely be possible to overcome the limitations of simple MC and BC systems by implementation of bilayered conduits fabricated by the overlapping of BC as inner layer and MC as outer layer. Moreover, bi-component electrospun fibers can be also aligned by applying a mechanical drawing during collection. At this point, the proposed bioartificial nerve graft provides topographic and biochemical cues indirect contact with neuronal cells in the luminal layer and ensures the mechanical stability required to guide the regenerating nerves until functional recovery is completely achieved, avoiding neurites misdirectional growth.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the 2011 International Summer Exchange Program at the New Jersey Center for Biomaterials, for sponsoring V. Cirillo's work at Rutgers University and Dr. Jack Hershey (Rutgers University) for performing the animal surgeries, Dr. Ijaz Ahmed (Rutgers University) for help with histological processing. This work has been financially supported by MERIT (RBNE08HM7T) and PON2-00029_3203241 (POLIFARMA). Scanning Electron Microscopy was supported by the Transmission and Scanning Electron Microscopy Labs (LAMEST) of the National Research Council of Italy.

References

- [1].Bian YZ, Wang Y, Aibaidoula G, Chen GQ, Wu Q. Evaluation of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) conduits for peripheral nerve regeneration. Biomaterials. 2009;30:217–25. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Nakayama K, Takakuda K, Koyama Y, Soichiro I, Wei W, Tomokazu M, et al. Enhancement of peripheral nerve regeneration using bioabsorbable polymer tubes packed with fibrin gel. Artif Organs. 2007;31:500–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2007.00418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Schnell E, Klinkhammer K, Balzer S, Gary B, Doris K, Paul D, et al. Guidance of glial cell migration and axonal growth on electrospun nanofibers of poly-ε-caprolactone and a collagen/poly-ε-caprolactone blend. Biomaterials. 2007;28:3012–25. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Deal DN, Griffin JW, Hogan MV. Nerve conduits for nerve repair or reconstruction. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;2:63–8. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-20-02-063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ezra M, Bushman J, Shreiber D, Schachner M, Kohn J. Enhanced femoral nerve regeneration after tubulization with a tyrosine-derived polycarbonate terpolymer: effects of protein adsorption and independence of conduit porosity. Tissue Eng A. 2014;20:518–28. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2013.0092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cao H, Liu T, Chew SY. The application of nanofibrous scaffolds in neural tissue engineering. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61:1055–64. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wang XD, Hu W, Cao Y, Yao J, Wu J, Gu XS. Dog sciatic nerve regeneration across a 30-mm defect bridged by a chitosan/PGA artificial nerve graft. Brain. 2005;128:1897–910. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Liu B, Cai SX, Ma KW, Xu ZL, Dai XZ, Li Y, et al. Fabrication of a PLGA–collagen peripheral nerve scaffold and investigation of its sustained release property in vitro. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2008;19:1127–32. doi: 10.1007/s10856-007-3224-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Oh SH, Kim JH, Song KS, Byeong HJ, Jin HY, Tae BS, et al. Peripheral nerve regeneration within an asymmetrically porous PLGA/pluronic F127 nerve guide conduit. Biomaterials. 2008;29:1601–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mohanna PN, Terenghi G, Wiberg M. Composite PHB–GGF conduit for long nerve gap repair: a long-term evaluation. Scand J Plast Recons. 2005;39:129–37. doi: 10.1080/02844310510006295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Young RC, Wiberg M, Terenghi G. Poly-3-hydroxybutyrate (PHB): a resorbable conduit for long-gap repair in peripheral nerves. Br J Plast Surg. 2002;55:235–40. doi: 10.1054/bjps.2002.3798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lu MC, Hsiang SW, Lai TY, Yao CH, Lin LY, Chen YS. Influence of cross-linking degree of a biodegradable genipin-cross-linked gelatin guide on peripheral nerve regeneration. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2007;18:843–63. doi: 10.1163/156856207781367747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chen YS, Chang JY, Cheng CY, Tsai FJ, Yao CH, Liu BS. An in vivo evaluation of a biodegradable genipin-cross-linked gelatin peripheral nerve guide conduit material. Biomaterials. 2005;26:3911–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.09.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chen MH, Chen PR, Chen MH, Hsieh ST, Huang JS, Lin FH. An in vivo study of tri-calcium phosphate and glutaraldehyde crosslinking gelatin conduits in peripheral nerve repair. J Biomed Mater Res Part B Appl Biomater. 2006;77B:89–97. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Kim SW, Bae HK, Nam HS, Chung DJ, Choung PH. Peripheral nerve regeneration through nerve conduit composed of alginate–collagen–chitosan. Macromol Res. 2006;14:94–100. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ahmed MR, Vairamuthu S, Shafiuzama M, Basha SH, Jayakumar R. Microwave irradiated collagen tubes as a better matrix for peripheral nerve regeneration. Brain Res. 2005;1046:55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Li WS, Guo Y, Wang H, Shi DJ, Liang CF, Ye ZP, et al. Electrospun nanofibers immobilized with collagen for neural stem cells culture. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2008;19:847–54. doi: 10.1007/s10856-007-3087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Waitayawinyu T, Parisi DM, Miller B, Luria S, Morton HJ, Chin SH, et al. A comparison of polyglycolic acid versus type 1 collagen bioabsorbable nerve conduits in a rat model: an alternative to autografting. J Hand Surg Am. 2007;32A:1521–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cerri F, Salvatore L, Memon D, Martinelli Boneschi F, Madaghiele M, Brambilla P, et al. Peripheral nerve morphogenesis induced by scaffold micropatterning. Biomaterials. 2014;35:4035–45. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.01.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lu GY, Kong LJ, Sheng BY, Wang G, Gong YD, Zhang XF. Degradation of covalently cross-linked carboxymethylchitosan and its potential application for peripheral nerve regeneration. Eur Polym J. 2007;43:3807–18. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wang AJ, Ao Q, Cao WL, Yu MZ, He Q, Kong LJ, et al. Porous chitosan tubular scaffolds with knitted outer wall and controllable inner structure for nerve tissue engineering. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2006;79A:36–46. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zhang P, Xu H, Zhang D, Fu Z, Zhang H, Jiang B. The biocompatibility research of functional Schwann cells induced from bone mesenchymal cells with chitosan conduit membrane. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol. 2006;34:89–97. doi: 10.1080/10731190500430198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wang AJ, Ao Q, Wei YJ, Gong K, Liu XS, Zhao NN, et al. Physical properties and biocompatibility of a porous chitosan-based fiber-reinforced conduit for nerve regeneration. Biotechnol Lett. 2007;29:1697–702. doi: 10.1007/s10529-007-9460-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Uebersax L, Mattotti M, Papaloizos M, Merkle HP, Gander B, Meinel L. Silk fibroin matrices for the controlled release of nerve growth factor (NGF) Biomaterials. 2007;28:4449–60. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Yang Y, Ding F, Wu J, Hu W, Liu W, Liu J, et al. Development and evaluation of silk fibroin-based nerve grafts used for peripheral nerve regeneration. Bio-materials. 2007;28:5526–35. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Willerth SM, Sakiyama-Elbert SE. Approaches to neural tissue engineering using scaffolds for drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2007;59:325–38. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Daly W, Yao L, Zeugolis D, Windebank A, Pandit A. A biomaterials approach to peripheral nerve regeneration: bridging the peripheral nerve gap and enhancing functional recovery. J R Soc Interface. 2012;9:202–21. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2011.0438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ngo TTB, Waggoner PJ, Romero AA, Nelson KD, Eberhart RC, Smith GM. Poly(L-lactide) microfilaments enhance peripheral nerve regeneration across extended nerve lesions. J Neurosci Res. 2003;72:227–38. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Stang F, Fansa H, Wolf G, Reppin M, Keilhoff G. Structural parameters of collagen nerve grafts influence peripheral nerve regeneration. Biomaterials. 2005;26:3083–91. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Jain A, Kim YT, McKeon RJ, Bellamkonda RV. In situ gelling hydrogels for conformal repair of spinal cord defects, and local delivery of BDNF after spinal cord injury. Biomaterials. 2006;27:497–504. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Flemming RG, Murphy CJ, Abrams GA, Goodman SL, Nealy PF. Effects of synthetic micro- and nanostructured surfaces on cell behavior. Biomaterials. 1999;20:573–88. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Neal RA, McClugage SG, Link MC, Sefcik LS, Ogle RC, Botchwey EA. Laminin nanofiber meshes that mimic morphological properties and bioactivity of basement membranes. Tissue Eng Part C. 2009;15(1):11–21. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2007.0366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Alvarez-Perez MA, Guarino V, Cirillo V, Ambrosio L. Influence of gelatin cues in PCL electrospun membranes on nerve outgrowth. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11:2238–46. doi: 10.1021/bm100221h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Guarino V, Alvarez-Perez MA, Cirillo V, Ambrosio L. hMSC interaction with PCL and PCL/gelatin platforms: a comparative study on films and electrospun membranes. J Bioact Comp Pol. 2011;26(2):144–60. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Alvarez Perez MA, Guarino V, Cirillo V, Ambrosio L. In vitro mineralization and bone osteogenesis in poly(ε-caprolactone)/gelatin nanofibers. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2012;100(11):3008–19. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].de Boer R, Knight AM, Borntraeger A, HeBert-Blouin MN, Spinner RJ, Malessy MJA, et al. Rat sciatic nerve repair with a poly-lactic-co-glycolic acid scaffold and nerve growth factor releasing microspheres. Microsurg. 2011;31(4):293–302. doi: 10.1002/micr.20869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kääriäainen M, Kauhane S. Skeletal muscle injury and repair: the effect of disuse and denervation on muscle and clinical relevance in pedicled and free muscle flaps. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2012;28(09):581–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1315784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Chen CC, Chan CY, Chen LS, Tsai FJ, Yao CH, Tsai CC, et al. Investigation of neurochemical techniques for assessment of nerve regeneration within polymer guides. J Med Biol Eng. 2011;32(2):131–8. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Lundborg PG, Rosén B, Abrahamson SO, Dahlinand L, Danielsen N. Tubular repair of the median nerve in the human forearm. Preliminary findings. J Hand Surg. 1994;19:273–6. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(94)90068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Gu X, Ding F, Yang Y, Liu J. Construction of tissue engineered nerve grafts and their application in peripheral nerve regeneration. Prog Neurobiol. 2010;93:204–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Amini AR, Wallace JS, Nukavarapu SP. Short-term and long-term effects of orthopedic biodegradable implants. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2011;21(2):93–122. doi: 10.1615/jlongtermeffmedimplants.v21.i2.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Reid AJ, de Luca AC, Faroni A, Downes S, Sun M, Terenghi G, et al. Long term peripheral nerve regeneration using a novel PCL nerve conduit. Neurosci Lett. 2013;544:125–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Rutkowski GE, Carole A. Heath development of a bioartificial nerve graft. II. Nerve regeneration in vitro. Biotechnol Prog. 2002;18:373–9. doi: 10.1021/bp020280h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Midha R, Munro CA, Dalton PD, Tator CH, Shoichet MS. Growth factor enhancement of peripheral nerve regeneration through a novel synthetic hydrogel tube. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:555–65. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.99.3.0555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Oh SH, Kim JR, Kwon GB, Namgung U, Song KS, Lee JH. Effect of surface pore structure of nerve guide conduit on peripheral nerve regeneration. Tissue Eng C. 2013;19(3):233–43. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2012.0221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Zhu Y, Wang A, Patel S, Kurpinski K, Diao E, Bao X, et al. Engineering bi-layer nanofibrous conduits for peripheral nerve regeneration. Tissue Eng Part C. 2011;17(7):705–15. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2010.0565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].de Luca AC, Terenghi G, Downes S. Chemical surface modification of poly-ε-caprolactone improves Schwann cell proliferation for peripheral nerve repair. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2012 doi: 10.1002/term.1509. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/term.1509. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [48].Croll TI, O'Connor AJ, Stevens GW, Cooper-White JJ. Controllable surface modification of poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) by hydrolysis or aminolysis. I: physical, chemical, and theoretical aspects. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5:463–73. doi: 10.1021/bm0343040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Yang J, Bei J, Wang S. Enhanced cell affinity of poly (D, L-lactide) by combining plasma treatment with collagen anchorage. Biomaterials. 2002;23:2607–14. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(01)00400-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Healy KE, Tsai D, Kim JE. Mater Res Soc Symp Proc. Pittsburg Materials Research Society. 1992;252:109. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Prabhakaran MP, Venugopal JR, Chyan TT, Hai LB, Chan CK, Lim AY, et al. Electrospun biocomposite nanofibrous scaffolds for neural tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14(11):1787–97. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Yu W, Zhao W, Zhu C, Zhang X, Ye D, Zhang W, et al. Sciatic nerve regeneration in rats by a promising electrospun collagen/poly(ε-caprolactone) nerve conduit with tailored degradation rate. BMC Neurosci. 2011;12(68):1–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-12-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Yang L, Fitie CF, van derWerf KO, Bennink ML, Dijkstra PJ, Feijen J. Mechanical properties of single electrospun collagen type I fibers. Biomaterials. 2008;29(8):955–62. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Jiang X, Lim SH, Mao HQ, Chew SY. Current applications and future perspectives of artificial nerve conduits. Exp Neurol. 2010;223(1):86–101. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Liang D, Hsiao BS, Chu B. Functional electrospun nanofibrous scaffolds for biomedical applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2007;59(14):1392–412. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Zeugolis DI, Khew ST, Yew ES, Ekaputra AK, Tong YW, Yung LY, et al. Electro-spinning of pure collagen nano-fibres e just an expensive way to make gelatin? Biomaterials. 2008;29:2293–305. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Gorgieva S, Kokol V. Collagen- vs. gelatine-based biomaterials and their biocompatibility: review and perspectives prof rosario pignatello (Ed.), ISBN: 978-953-307-661-4. InTech. Available from: http://www.intechopen.com/books/biomaterials-applications-for-nanomedicine/collagen-vs-gelatine-basedbiomaterials-and-their-biocompatibility-review-and-perspectives.

- [58].Kokare CR. Nirali Prakashan. Pune, India: 2008. Pharmaceutical microbiology-principles and applications. ISBN NO.978-81-85790-61-2. [Google Scholar]

- [59].Ghasemi-Mobarakeh L, Prabhakaran MP, Morshed M, Nasr-Esfahani MH, Ramakrishna S. Electrospun poly(3-caprolactone)/gelatin nanofibrous scaffolds for nerve tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2008;29:4532–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Gerardo-Nava J, Fuhrmann T, Klinkhammer K, Seiler N, Mey J, Klee D, et al. Human neural cell interactions with orientated electrospun nanofibers in vitro. Nanomedicine. 2009;4:11–30. doi: 10.2217/17435889.4.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Lee YS, Arinzeh TL. Electrospun nanofibrous materials for neural tissue engineering. Polymers. 2011;3:413–26. [Google Scholar]

- [62].Chew SY, Wen Y, Dzenis Y, Leong KW. The role of electrospinning in the emerging field of nanomedicine. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12(36):4751–70. doi: 10.2174/138161206779026326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Guarino V, Cirillo V, Taddei P, Alvarez-Perez MA, Ambrosio L. Tuning fiber size mesh and crystallinity of PCL electrospun membranes by solvent permittivity and influence on hMSC response. Macromol Biosci. 2011;12:1694–705. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201100204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Son WK, Youk JH, Lee TS, Park WH. The effects of solution properties and polyelectrolyte on electrospinning of ultrafine poly(ethylene oxide) fibers. Polymer. 2004;45:2959–66. [Google Scholar]

- [65].Woo KM, Chen VJ, Ma PX. Nano-fibrous scaffolding architecture selectively enhances protein adsorption contributing to cell attachment. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;67(2):531–7. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Guaccio A, Guarino V, Alvarez-Perez MA, Cirillo V, Netti PA, Ambrosio L. Influence of electrospunfibre mesh size on hMSC oxygen metabolism in 3D collagen matrices: experimental and theoretical evidences. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2011;108(8):1965–76. doi: 10.1002/bit.23113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Kokai LE, Lin YC, Oyster NM, Marra KG. Diffusion of soluble factors through degradable polymer nerve guides: Controlling manufacturing parameters. Acta Biomater. 2009;5:2540–50. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Wolthers M, Moldovan M, Binderup T, Schmalbruch H, Krarup C. Comparative electrophysiological, functional, and histological studies of nerve lesions in rats. Microsurg. 2005;25(6):508–19. doi: 10.1002/micr.20156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Smit X. A rat sciatic nerve study on fundamental problems of peripheral nerve injury. 2006. ISBN-13: 978-90-9020531-1. [Google Scholar]

- [70].Wang W, Itoh S, Matsuda A, Ichinose S, Shinomiya K, Hata Y, et al. Influences of mechanical properties and permeability on chitosan nano/microfiber mesh tubes as a scaffold for nerve regeneration. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;84(2):557–66. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]