Abstract

Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) production is impaired in cord blood monocytes. However, the mechanism underlying this developmental attenuation remains unclear. Here, we analyzed the extent of variability within the Toll-like receptor (TLR)/NLRP3 inflammasome pathways in human neonates. We show that immature low CD14-expressing/CD16pos monocytes predominate before 33 weeks of gestation, and that these cells lack production of the pro-IL-1β precursor protein upon LPS stimulation. In contrast, high levels of pro-IL-1β are produced within high CD14-expressing monocytes, although they are unable to secrete mature IL-1β. The lack of secreted IL-1β in these monocytes parallels a reduction of TLR-mediated NLRP3 induction resulting in a lack of caspase-1 activity before 29 weeks of gestation, whereas expression of the ASC protein and function of the P2X7 receptor are preserved. Our analyses also reveal a strong inhibitory effect of placental infection on LPS/ATP-induced caspase-1 activity in cord blood monocytes. Lastly, secretion of IL-1β in preterm neonates is restored to adult levels during the neonatal period, indicating rapid maturation of these responses after birth. Collectively, our data highlight important developmental mechanisms regulating IL-1β responses early in gestation, in part due to a downregulation of TLR-mediated NLRP3 expression. Such mechanisms may serve to limit potentially damaging inflammatory responses in a developing fetus.

Keywords: Neonate, Interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), Inflammasome, Toll-like receptor, Human

Introduction

Newborns are at high risk of infections, in part due to attenuated innate immune defenses [1]. The cytokine interleukin-1β (IL-1β) is an important inflammatory mediator in response to infections [2]. Mice lacking IL-1β display impaired acute phase and pyrogenic responses [3], and increased susceptibility to pathogens commonly encountered in the neonatal period [4, 5]. In contrast, high levels of IL-1β in a fetus can result in autoimmune organ damage [2], as well as lethal metabolic disturbances including severe weight loss and hypoglycemia [6]. Together, these data illustrate the evolutionary importance of a tight regulation of IL-1β in order to avoid inflammation-mediated organ damage, neurological injury [7] or even premature birth in a developing human [2, 8].

Monocytes are primarily responsible for the production of IL-1β in circulating blood [9, 10]. Three subsets predominate in humans: ‘Classical’ monocytes express CD14, but lack expression of the immunoglobulin receptor CD16. These CD14high/CD16negmonocytes make up the majority of monocytes in peripheral adult blood, and have been proposed to be capable of producing high amounts of IL-10 [11]. In contrast, the smaller, non-classical CD14low/CD16pos monocytes express high levels of the antigen-presenting molecule HLA-DR [12], as well as cytokine TNF-α [13]. This latter subset has been proposed to play an important immediate responder ‘proinflammatory’ role in sepsis [11, 14, 15]. Finally, a third subset of monocytes expressing high levels of CD14, as well as CD16 (CD14high/CD16pos) may play a more intermediate role in inflammation [16].

Production of IL-1β differs from that of most other inflammatory cytokines as it requires a dual signal for its activation [2]. First, intracellular pro-IL-1β is produced following stimulation of pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) such as the Toll-like receptors (TLRs). Second, in order to be functional pro-IL-1β requires proteolytic cleavage, predominantly by caspase-1, a component of the NLRP3 inflammasome multi-protein complex, resulting in secretion of mature, biologically active IL-1β [17]. Activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome can be triggered by local mediators of host cell damage in vivo (e.g. free radicals, DNA or adenosine triphosphate: ATP, through the purinoceptor P2X7) [18]. Earlier studies showed that IL-1β production is markedly reduced in human cord blood monocytes in response to endotoxin (LPS) [19, 20]. Caspase-1 processing was also reduced in term neonates [21]. However, the functional consequence of this reduced caspase-1 processing on neonatal IL-1β responses has never been functionally characterized.

In order to understand the molecular basis for the regulation of IL-1β secretion in monocytes in humans at an early stage in life, we analyzed the developmental variability in the TLR and NLRP3 inflammasome pathways in neonates born late in gestation. Given the need for a tight regulation of IL-1β responses in order to avoid major metabolic disturbances in the fetus, we hypothesized that the NLRP3 inflammasome is regulated in a discrete manner before the term of gestation.

Results

Immature monocytes in cord blood before the term of gestation

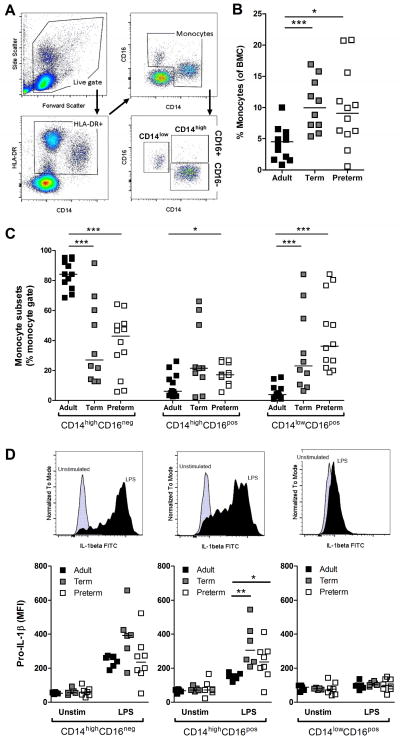

Data are greatly lacking regarding the ontogeny of monocyte subsets in humans. To address this, we first analyzed subsets of monocytes in preterm, term and adult subjects, using standard flow cytometry gating strategy, as defined previously [22] (figure 1A). Expectedly, cumulative proportions of monocytes were generally preserved in cord blood relative to blood mononuclear cells (BMC) (figure 1B). Also, monocytes from all three age groups displayed comparable expression of the myeloid markers CD33 and CD11c, whereas expression of HLA-DR was reduced in preterm cord blood (Supporting Information figure 1). Notably, we observed a predominance of CD14low/CD16pos monocytes in preterm cord BMC (figure 1C), and this subset of monocytes did not express any detectable intracellular pro-IL-1β upon LPS stimulation, suggesting that they represent an immature form (figure 1D).

Figure 1. Phenotype of human monocytes comparing cord blood to adults.

(A) Representative flow cytometry gating strategy used to identify monocytes subsets. (B) Cumulative percentage of monocytes relative to BMCs in preterm, term and adult subjects. (C) Proportion of monocytes subsets according to CD14 and CD16 expression in BMCs. (D) Intracellular pro-IL-1β production following LPS induction, in each monocyte subset; top panels display representative pro-IL-1β flow cytometry histograms for each subset. (B–D) Preterm subjects were 28.6±2.6 weeks of gestation (mean±SD). (AD) Data are representative of at least 2 independent experiments performed using batch reagents and standardized flow cytometry voltage settings, where n = 6–12 subjects were included per age group. Bars represent medians. MFI: Mean Fluorescence Intensity; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001, Mann-Whitney U test.

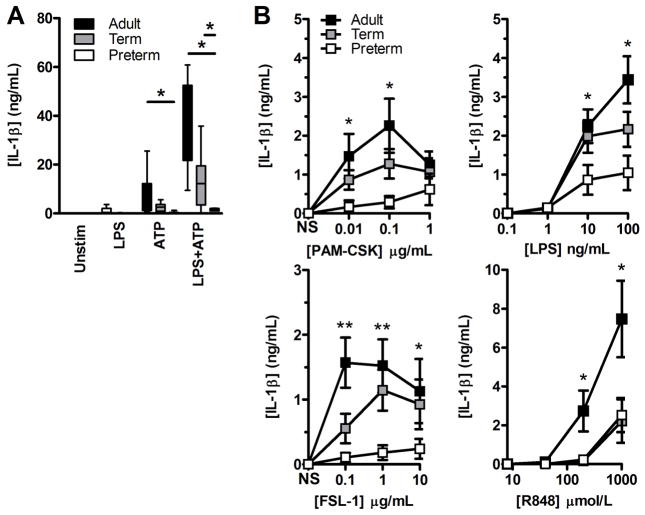

In contrast, when testing the functional capacity of the cord blood high CD14-expressing subset of monocytes, both CD16pos and CD16neg subsets expressed levels of intracellular pro-IL-1β comparable (if not higher than) to that of adult peripheral blood (figure 1D). In these cells, IL-1β secretion was also profoundly reduced at decreasing gestation, as confirmed on a per cell basis, and was not restored following co-activation of the inflammasome (figure 2A). To exclude a contribution of low CD14-expressing monocytes to IL-1β secretion, negatively purified monocytes were similarly assayed, and yielded identical results (not shown). This lack of mature IL-1β secretion at decreasing gestation was also observed regardless of the TLR engaged (figure 2B). Altogether, these data demonstrate a profound impairment of IL-1β production in high-CD14-expressing preterm monocytes despite intracellular detection of pro-IL-1β.

Figure 2. TLR-induced IL-1β responses in high CD14-expressing monocytes.

(A) Secreted IL-1β in culture supernatants of positively selected CD14-expressing monocytes after stimulation with LPS ± ATP was measured by ELISA. Box and whiskers graph showing median + interquartile range. (B) Secreted IL-1β in culture supernatants of BMCs after stimulations with other TLR agonists [in brackets]. Data are shown as mean±SEM and are representative of one experiment performed, which included 4–6 subjects per group. (A and B) Preterm subjects were 28.8±1.8 weeks of gestation (mean±SD) and between 26 and 30 weeks, respectively. *p<0.05; **p<0.01, Mann-Whitney U test.

Reduced TLR-induced IL-1β response in high CD14-expressing preterm monocytes

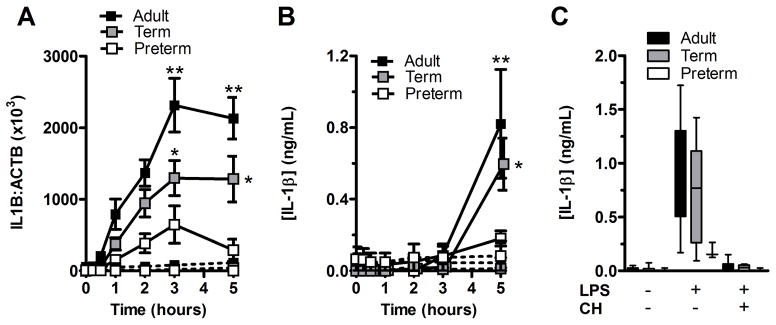

As shown above, pro-IL-1β was detectable in high CD14-expressing preterm monocytes. To better understand the molecular basis for the developmental inability of monocytes to secrete IL-1β, we examined whether expression of the IL1B transcript was induced following LPS stimulation. Indeed, expression of the IL1B gene was significantly reduced at lower gestation (figure 3A). In parallel experiments, secretion of IL-1β in whole blood was also markedly impaired indicating that the gestational age-dependent attenuation in IL-1β secretion is not due to a lack of serum factor(s) excluded during the BMC purification (figure 3B). Treatment of cells with cycloheximide prior to LPS stimulation also completely abrogated secretion of IL-1β, consistent with a de novo requirement for protein expression following LPS challenge, in order to produce mature IL-1β in all three age groups (figure 3C). Moreover, production of the inflammasome-independent cytokine IL-6 was similarly impaired, consistent with a hyporesponsive response intrinsic to the TLR component of the TLR/inflammasome pathway in cord blood monocytes (Supporting Information figure 2C).

Figure 3. TLR-induced cytokine gene and protein expression are impaired in preterm neonates.

(A) Kinetics of IL1B mRNA expression following LPS stimulation was measured by real-time PCR. Data represent the ratio of IL1B to ACTB (β-actin) transcript copy numbers of experiments performed on whole blood samples in duplicates (solid lines = LPS stimulation; dashed lines = unstimulated cells). (B) Kinetics of IL-1β protein secretion in culture supernatants from subjects simultaneously tested in (A) was measured by ELISA. Levels of statistical significance were only indicated for comparisons with preterm subjects. (A and B) Data are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 6 subjects per group) and are representative of 2 independent experiments performed. Preterm subjects for this figure were 28.7±1.8 weeks of gestation (mean±SD). (C) Box and whiskers graph showing median + interquartile range of LPS-induced IL-1β secretion with or without cycloheximide (CH) added at the beginning of stimulation. IL-1β concentration was measured by ELISA. Preterm subjects were 28.8±1.8 weeks of gestation. Data are shown as mean ± SD (n=4–6 subjects per group) and are representative of one experiment performed. *p<0.05; **p<0.01, Mann-Whitney U test.

Adult-like production of pro-IL-1β in high CD14-expressing preterm neonatal monocytes

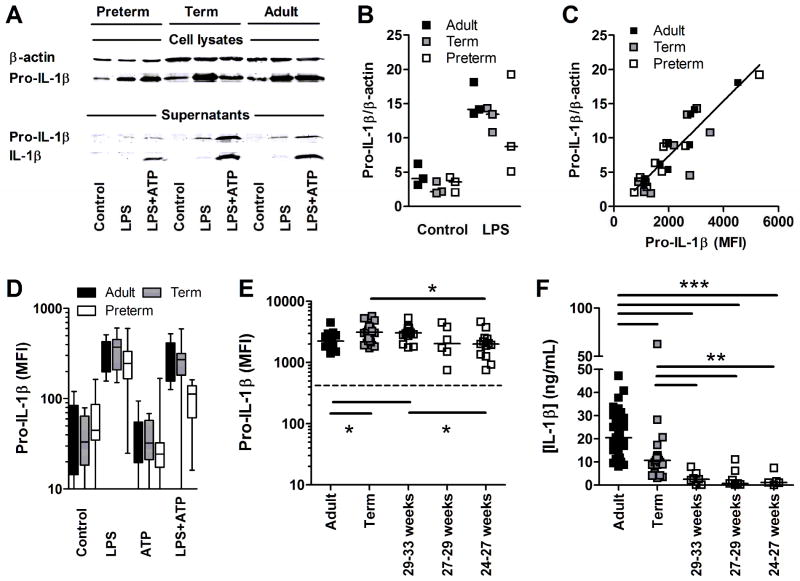

To further validate the production of pro-IL-1β in high CD14-expressing cells, despite their lack of IL-1β secretion, we used a combination of western blot (full uncut western blots are provide in Supporting Information figure 3), flow cytometry and ELISA experiments. Western blot experiments confirmed a reduction in secreted IL-1β in culture supernatants after LPS/ATP stimulation (figure 4A). Western blot experiments also confirmed the marginal reduction in pro-IL-1β in LPS-stimulated preterm monocytes, compared to term and adult monocytes (figure 4A), after normalization to β-actin (figure 4B). However, because western blots are not ideal for quantifying proteins, we combined this method with the more quantitative flow cytometry detection. Importantly, when combining age groups and stimulation conditions in parallel experiments, we confirmed a high correlation between the amount of precursor pro-IL-1β protein detected in purified monocytes by western blot, and the pro-IL-1β protein detected by flow cytometry (Spearman’s coefficient r = 0.88; p<0.0001; figure 4C). With this result, we also demonstrate that our flow cytometry is indeed detecting mainly pro-IL-1β in precursor form. Then, using flow cytometry, we confirmed that LPS-induced preterm monocytes can produce levels of pro-IL-1β comparable to adults stratifying preterm subjects by gestational age categories (figure 4D, E), despite a complete lack of secreted IL-1β at the lower gestational ages tested (figure 4F). These results confirm that pro-IL-1β accumulates intracellularly and is unable to be secreted in preterm cord blood monocytes.

Figure 4. Accumulation of intracellular pro-IL-1β precursor in monocytes.

(A) Representative western blot showing pro-IL-1β/IL-1β production in cell lysates of positively selected monocytes (top panel) or in culture supernatants (bottom panel) after stimulation with LPS±ATP, or in unstimulated. Results are from one experiment representative of three independent experiments performed. β-actin was used as a loading control. (B) Densitometry of pro-IL-1β normalized on β-actin from all three western blots including 3 preterm subjects born at 24, 26 and 30 weeks of gestation. Data represent 3 independent experiments. (C) Correlation between pro-IL-1β detected by western blot versus flow cytometry in positively selected monocytes based on parallel experiments combining preterm, term and adults (Spearman’s coefficient r = 0.88; p<0.0001). (D) Detection of intracellular pro-IL-1β (FITC) and (E) detection of intracellular pro-IL-1β (Alex Fluor-647; dashed line = detection in fluorescence minus-one staining controls) after LPS stimulation, in high CD14-expressing monocytes, by flow cytometry. (F) Secreted levels of IL-1β (ELISA) after LPS/ATP stimulation in preterm subjects (BMCs) categorized by gestational age. (D–F) Data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments performed, where up to12–25 subjects per group were included. Bars represent medians. MFI: Mean Fluorescence Intensity; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001, Mann-Whitney U test.

Lack of NLRP3 induction in preterm monocytes following TLR stimulation

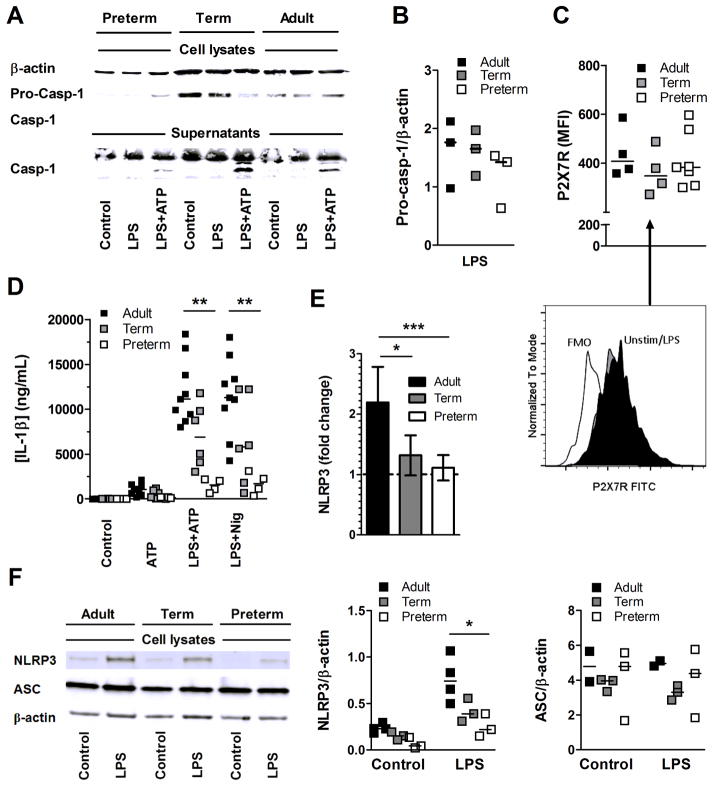

We next asked whether the activity of the NLRP3 inflammasome was impaired in preterm cord blood monocytes. First, we determined whether both pro-caspase-1 (figure 5A, B) and the upstream P2X7 receptor, whose activation is required for assembly of the NLRP3 inflammasome, were expressed in comparable levels in high CD14-expressing preterm, term and adult monocytes; and this was the case (figure 5C). In addition, secretion of IL-1β by preterm monocytes was not restored using nigericin, which bypasses the need for activation of the P2X7 receptor for IL-1β production [23], suggesting that the developmental limitation in production of this cytokine lies downstream of the purinoceptor (figure 5D). Others have shown that NLRP3 expression is inducible following TLR stimulation and its upregulation is necessary in order to activate caspase-1 and to produce mature IL-1β [24]. When analyzing preterm cord blood monocytes, TLR-induced NLRP3 upregulation was substantially impaired upon activation of cells with LPS at lower gestation; this finding was evidenced using real-time PCR, where induction of NLRP3 after LPS versus unstimulated was significantly greater in adults compared to preterm subjects (figure 5E). Results were also validated at the protein level in western blot (figure 5F). In comparison, expression of ASC was maintained (figure 5F). These results suggested that the TLR-mediated induction of NLRP3 in high CD14-expressing monocytes is limiting activation of the caspase-1 NLRP3 inflammasome during gestation. Furthermore, our data provide a novel regulatory mechanism potentially limiting IL-1β responses downstream of TLR/NF-κB activation and pro-IL-1β protein expression, during gestation.

Figure 5. Impaired NLRP3 induction in preterm neonatal monocytes.

(A) Representative western blot of pro-caspase-1 (Pro-Casp-1) processing into active caspase-1 (Casp-1) after LPS±ATP in preterm, term and adult positively selected CD14-expressing monocytes. Results are from one experiment representative of three independent experiments performed. β-actin was used as a loading control. (B) Ratio of pro-caspase-1 over β-actin band intensity as detected by western blot in three independent experiments, including preterm subjects born at 24, 26 and 30 weeks of gestation. (C) Expression of P2X7R on high CD14-expressing monocytes after LPS induction; Representative flow cytometry histogram (lower panel in C); MFI: Mean Fluorescence Intensity. (D) IL-1β secretion (ELISA) after LPS±ATP or nigericin.(E) Real time PCR analysis of NLRP3 mRNA expression (fold-change compared to unstimulated) after stimulation of positively selected CD14-expressing monocytes with or without LPS; Data is normalized against ACTB. Data is shown as mean ±SEM and is representative of one real-time PCR experiment performed in triplicates, including 8 adults, 8 term and 6 preterm subjects born between 24 to <28 weeks of gestation. (F) Representative western blot showing protein validation of NLRP3 and ASC expression following LPS stimulation in positively selected CD14-expressing monocytes (from a preterm neonate 27 weeks of gestation). Results are from one experiment representative of three independent experiments performed (left panel). β-actin was used as a loading control. Densitometry of NLRP3 (middle panel) and ASC (right panel) quantification by western blots (normalized on β-actin) in positively selected CD14-expressing monocytes with or without LPS. Data represent 3 independent experiments performed. Bars represent medians, n = 3 different subjects per group. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001, Mann-Whitney U test, except for (E) where an ANOVA was used with a posttest Bonferroni correction.

Developmental lack of caspase-1 activity early in the third trimester of gestation

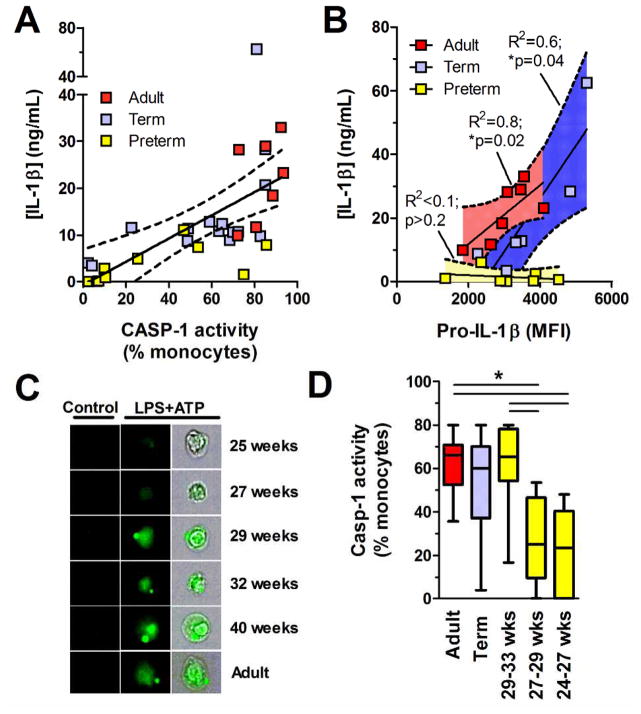

We use flow microscopy to determine the impact of the developmental lack of TLR-mediated NLRP3 induction on the activity of the caspase-1 (Supporting Information figure 4). In parallel experiments, LPS/ATP-mediated activation of caspase-1 was well correlated with IL-1β secretion in BMC culture supernatants in all three age groups (Spearman’s coefficient r = 0.69; p<0.0001; figure 6A). On the other hand, in preterm neonates there was no correlation between LPS-mediated production of pro-IL-1(beta) and LPS/ATP-mediated IL-1(beta) secretion. IL-1β secretion remained low even at high levels of intracellular pro-IL-1β, suggesting a lack of caspase-1 activity (figure 6B). To confirm this hypothesis, we quantified both production of intracellular pro-IL-1β and activity of caspase-1 on a per-cell basis, gating on high CD14-expressing monocytes. In term neonates, peak caspase-1 activity was comparable to adult levels. However, it became significantly impaired below 29 weeks of gestation, reaching undetectable levels at 24 to <27 weeks of gestation (figure 6C, D). Overall, our results show that activation of caspase-1 is profoundly limited in high CD14-expressing monocytes from preterm cord blood, leading to accumulation of pro-IL-1β at lower gestation.

Figure 6. Caspase-1 activity in CD14-expressing monocytes.

(A) Linear regression (solid line; dashed lines = 95%CI) between caspase-1 activity (flow cytometry, gated on high CD14-expressing cells) and secreted IL-1β (ELISA), after stimulation with LPS+ATP. (B) Linear regressions (solid lines; dashed lines with shaded areas = 95%CI) between LPS-stimulated pro-IL-1β in high CD14-expressing monocytes and LPS+ATP-stimulated IL-1β production in culture supernatants (ELISA). (A and B) Symbols represent individual subjects. (C) Flow microscopy detection (40X magnification) of active caspase-1 (green) following LPS+ATP (representative neonatal and adult subjects) and unstimulated control cells (gated on high CD14-expressing monocytes). Third column shows caspase-1 activity superimposed on bright field cell image. (D) Caspase-1 activity after LPS+ATP stimulation. Bar represents median. Box and whisker graph shows median and interquartile range, n = 6–13 subjects per group. Data are pooled from independently performed experiments. *p<0.05, Mann-Whitney U test. (A, B) Data are pooled from 7 independent experiments where pro-IL-1β (flow cytometry), IL-1β (ELISA) and caspase-1 activity (flow cytometry) were measured in parallel. MFI: Mean Fluorescence Intensity.

Placental infection contributing to developmental lack of inflammasome activity during gestation

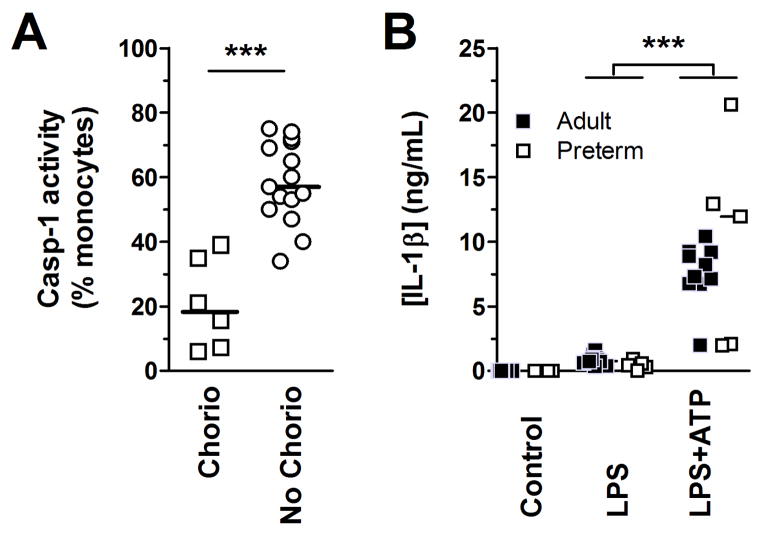

In the next series of experiments, we sought to identify clinical factors that may impact the activity of caspase-1 in human cord blood monocytes. To do so, we measured caspase-1 activation in a larger group of preterm neonates (n = 21). Upon examination of factors commonly associated with prematurity (i.e. chorioamnionitis, twin delivery, use of antenatal corticosteroids), we found significantly lower caspase-1 activity in monocytes from preterm subjects in presence of histological chorioamnionitis (figure 7A), whereas the former was not affected by twin delivery or use of antenatal corticosteroids (p>0.2; details of cases provided in Supporting Information table 1). In regression analyses, the association between caspase-1 activity and chorioamnionitis in preterm subjects remained statistically significant after adjusting for gestational age, indicating an independent effect (r2= 0.69; p<0.0001). Our results implicate a role for fetal infection regulating activity of the NLRP3 inflammasome in utero.

Figure 7. Intra-uterine and postnatal maturation in inflammasome activity.

(A) Caspase-1 activity, in monocytes (gated on high CD14-expressing cells; using FLICA), of preterm subjects with or without histological chorioamnionitis. Caspase-1 activity was measured after stimulation of BMCs with LPS+ATP. For this panel, preterm subjects were 28.2±1.0 and 29.5±2.1 weeks of gestational age (mean±SD) with and without chorioamnionitis, respectively (flow cytometry). (B) IL-1β secretion in whole peripheral blood stimulated with a supra-saturating dose of LPS (100 ng/mL) (ELISA). The blood for these studies was obtained from preterm subjects born 24 to <29 weeks of gestation (white squares), sampled at 7 to 28 days of age, compared to healthy adults. Data are pooled from 5 independent experiments performed. Symbols represent individual subjects, bar represents median, n = 5–10 subjects per group ***p<0.001, Mann-Whitney U test.

Production of IL-1β rapidly matures after birth in preterm neonates

Finally, we asked how long does the developmental attenuation in IL-1β secretion persists after birth? To this end, we directly examined the most downstream functional outcome of IL-1β secretion as the main outcome, on peripheral blood of preterm neonates (mean±SD: 15±11 [range 7–35] days of postnatal age). Responses obtained similarly in adults were used as a reference. In neonates born between 24 and 29 weeks of gestation, secretion of IL-1β, upon ATP/LPS stimulation, was heterogeneous but similar to adults during the neonatal period (figure 7B). These data suggest that the developmental impairment in IL-1β secretion is restored after birth.

Discussion

Earlier studies have established that cord blood monocytes are impaired in their ability to produce IL-1β upon endotoxin stimulation [20]. However, due to significant ethical challenges in studying neonatal subjects, the developmental aspects, as well as the mechanism(s) regulating IL-1β responses in humans remained unexplored at this early stage of life. In this study, we systematically investigated main rate-limiting components along the TLR and inflammasome pathways leading to the processing and secretion of IL-1β. The reduction in IL-6, IL1B gene and NLRP3 gene expression suggest a general decrease in TLR signaling (signal 1) due to a gestational age-dependent immaturity of transduction pathway(s) or deficient TLR expression, as reported [25]. However, our results implicate an additional level of regulation in the inflammasome due to a lack of NLRP3/caspase-1 activation (signal 2). Overall, our data provide novel insights into key mechanisms regulating IL-1β responses during fetal life. To our knowledge, our study is the first to functionally assess the inflammasome developmentally in human neonates.

During development, monocytes appear in circulating blood as early as the first trimester of gestation. Our findings that cord blood CD16pos monocytes are abundant in late (third trimester) gestation are consistent with data from others [26, 27]. Yet, we provide new evidence for a functional immaturity of monocytes at this stage. High expression of CD16 on monocytes has been shown to correlate with increased clearance of pathogens at the site of infection [11–13, 15], which may help compensate for the lack of IL-1β in the early neonatal period. On the other hand, the lack of LPS-mediated pro-IL-1β response in CD14low monocytes potentially represents an early developmental stage at which monocyte IL-1β responses are dispensable. Of note, CD14 is required for TLR4 signaling, which may, in part, explain the lack of response of CD14low monocytes to LPS [28, 29]. Our data may indicate potential developmental preferences for certain responses at the expense of others, in order to maximize survival of the fetus.

Recently, processing of the caspase-1 enzyme was shown to be reduced in term neonates, although without a functional characterization of the inflammasome activity it was impossible to determine its impact on the production of IL-1β [21]. In fact, adult-like levels of caspase-1 activity were detected in term neonates in our study, suggesting that the reduction in caspase-1 cleavage previously reported in term neonates is functionally negligible [21]. A key finding of our research is that preterm monocytes express levels of the pro-IL-1β precursor protein similar to adult monocytes upon TLR stimulation, despite a marked reduction in IL1B gene expression. Previous studies have shown dissociation between pro-IL-1β protein expression such that protein levels can be maintained in human monocytes over important variations in IL1B transcript levels due to posttranscriptional regulatory events [30, 31]. This characteristic likely warrants an additional level of suppression of IL-1β responses through a regulation of caspase-1, as shown in our study.

Indeed, excessive inflammation can have major adverse health consequences in developing fetuses [1]. In sheep, intra-amniotic endotoxin causes an increase in proinflammatory gene expression in the lungs [32]. This strong inflammatory response parallels an increase in local inflammatory cell infiltration, resulting in IL-1-mediated organ injury [32]. Hence, responses triggered by microbial pathogens during fetal life, may cause tissue damage and oxidative stress which can be equally damaging during critical phases of organ development [2]. The harmful effects of an excessive production of IL-1β at this age is also evidenced from humans with rare mutations causing over-activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome as the Neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID). Subjects with this condition often develop severe arthritis, chronic meningitis leading to neurologic damage [33]. Because NLRP3 is a key player in the regulation of caspase-1-mediated IL-1β secretion from multiple different sources [34], centrally limiting induction of this protein provides a unifying mechanism through which fetuses can potentially limit cellular IL-1β responses to a variety of stimuli. Indeed caspase-1 is not solely activated through the NLRP3 inflammasome. However, its induction is critical for maximal IL-1β secretion early on (<12 hours) [35, 36]. Caspase-8 is also known to be involved in the late, non-canonical processing of pro-IL-1β, although its contribution to TLR-mediated responses is more marginal [37, 38]. More recently, cathepsin C has also been implicated in processing of pro-IL-1β in mice in vivo, but whether this is also true of humans’ remains is unclear [39].

Another key result of our study is the demonstration that preterm neonates’ ability to produce IL-1β was restored to adult levels quickly after birth, within 2 weeks of age indicating a rapid maturation of this pathway during the neonatal period. Based on previous observations, we speculate that the high production of placental-derived prostaglandins play an important role in suppressing IL-1β responses before birth [40]. Our finding that chorioamnionitis negatively regulates caspase-1 activity is also of clinical relevance, as delivery in conditions of high prematurity is frequently associated with infections [41]. In mice, chronic inflammation triggers the ubiquitin-mediated targeted degradation of the NLRP3 complex through autophagy [42, 43]. Fetal control over the inflammasome activity in presence of infection has, to the best of our knowledge, not been previously reported in humans. Again, given the potentially harmful effect of IL-1β in a fetus, inhibition of this cytokine in the context of an infection in utero may represent an evolutionary advantage [44, 45].

In conclusion, we identify a central developmental role for NLRP3 in regulating IL-1β during gestation, and potentially also after birth. A better understanding of the mechanisms regulating inflammatory responses in early life may provide critical insights into our understanding of the dysregulation of IL-1β pathways in human diseases as well as also shed important light towards a therapeutic exploitation of these mechanisms in prevention of neonatal sepsis.

Materials and methods

Recruitment of human subjects and blood sample collection

Cord blood was collected from either healthy neonates born at term or from preterm neonates born between 24 and 32 weeks of gestation at the Children’s & Women’s Health Centre of British Columbia (C&W). Peripheral blood was collected from healthy adult volunteers and preterm neonates 1 to 28 days of age. Due to ethical limitations, peripheral blood was not obtained from term neonates for comparison of postnatal responses. All blood samples were collected in sodium heparin-anticoagulated Vacutainers (BD Biosciences) and processed within 2 hours of collection. Chorioamnionitis was determined by a blind examination of micro-dissection slides by a medical pathologist, and was defined as maternal stage 1 or greater [46]. Informed consent was obtained for all subjects. Our study was approved by the C&W Research Ethics Board.

Cell purification, stimulation and cytokine detection

Peripheral or cord BMCs were cultured as described [47]. High CD14-expressing monocytes were purified from fresh BMCs by positive selection using EasySep™ for Human Monocyte (StemCell, Canada). Each aliquot of purified monocytes was analyzed by flow cytometry using a CD14-PeCy7-conjugated antibody to ensure >95% enrichment. Purified BMC (5.0 × 105 cells/well) or monocytes (5.0 × 105 cells/well) were stimulated for 5 hours with or without lipopolysaccharides (LPS, 10 ng/mL,), with or without ATP (5 mM, MP Biomedical), or nigericin (30 μM, Invivogen) added during the last hour of culture, as indicated. These conditions were chosen based on pilot experiments where we determined that pro-IL-1β cytokine expression started as early as 1 hour and peaked ~5 hours after stimulation in all three age groups (data not shown). Secreted IL-1β experiments comparing age groups were also carried out at 24 hours in order to exclude kinetic effects (Supporting Information figure 1A, B). PAM-CSK (Pam3Cys-SKKKK, TLR1/2 agonist) and R-FSL-1 (TLR2/6 agonist) were obtained from EMC microcollection (catalog#L2000 and L7022, respectively). LPS (TLR4 agonist) and R848 (TLR7/8 agonist) were obtained from InvivoGen. Following stimulation, cells were stained for flow cytometry analyses as described [47]. IL-1β and IL-6 in culture supernatants were quantified in batches by Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSorbent Assay (ELISA, eBioscience), in duplicate with coefficients of variability <20% (not shown).

Detection of intracellular IL-1β production and caspase-1 activation

Subsets of monocytes were characterized by staining fresh BMCs (stimulated or controls) with fluorescent-conjugated monoclonal antibodies against the cell surface markers CD14 (PE-Cy7), CD16 (eFluor 450), CD33 (PE; all from eBioscience), HLA-DR (PerCp-Cy5.5, BD Biosciences), CD33 (PE, eBioscience), CD11c (AF 700, BD Pharmingen), a rabbit polyclonal antibody against the P2X7-receptor (FITC; Alomone Labs, Israel), or against intracellular IL-1β (FITC- or Alexa fluor-647-conjugated, eBioscience). In preliminary experiments, caspase-1 activation peaked within 60 min of ATP stimulation in preterm, term and adult monocytes; therefore, all caspase-1 activation was assayed after no more than one hour in order to maximize response but minimize apoptosis (not shown). For detection of intracellular IL-1β, cells were stained using staining buffer (eBioscience). For caspase-1 activation (expressed as percentage activated cells), cells were stained using the FITC-conjugated Fluorescent-Labeled Inhibitor of Caspase-1 Activity (FLICA) Z-YVAD (ABD Serotec) as described [48] (Supporting Information figure 4). Data were acquired immediately after staining of cells on an LSR-II™ flow cytometer (Becton Dickenson) or on an ImageStreamX imaging instrument (Amnis Corporation). For data acquisition, standard voltage settings were set for each experiment using cells, including fluorescence-minus-one (FMO) controls. Signals were compensated using single color positive and negative control CompBeads (BD Biosciences). Flow cytometry data were analyzed with FlowJo vX.0.7 (TreeStar Inc., OR) for Windows (Microsoft, WA).

Real-time PCR experiments

Primer sequences used for PCR amplification are provided as Supporting Information data. For NLRP3 gene expression, experiments were carried out in CD14-magnetic column purified monocytes. For IL1B gene expression, because expression of the IL-1β protein was only significantly detected within high CD14-expressing monocytes and due to often limited obtainable blood volumes, expression experiments were carried out in whole blood. In this case whole blood was mixed 1:1 with RPMI medium. Following stimulation, samples (cell pellets) were immediately frozen (dry ice) and stored at −80°C for batch analyses. Cycloheximide (10 μg/mL, Sigma Aldrich) was added at the beginning of stimulation as indicated. Upon analysis, mRNA was extracted using the TRIzol LS method (Invitrogen), followed by an RNeasy column cleanup step (Qiagen). DNAse (Qiagen) I-treated RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using the High Capacity cDNA RT kit (Applied Biosystems). Real-time PCR was performed on a LightCycler® 480 System (Roche), using the LightCycler SYBR Green I Master (Roche). All gene amplifications were performed in triplicates. Sample cDNA copy numbers were calculated based on the standard curve generated by serial dilutions of DNA plasmids containing each gene studied, using the second derivative amplification threshold values (Ct). For NLRP3, real-time PCR was performed on a ViiA 7 System (Applied Biosystems). PCR efficiencies were similar (>1.95) for all genes. Inter-replicate coefficients of variability were <10%. Gene expression levels were normalized to that of β-actin (IL1B:ACTB). Similar results were obtained whether normalizing gene expression to ACTB or GAPDH (not shown).

Western blots experiments

Following incubation, cells (5.0 × 105 cells) were washed once with PBS and lysed in 10% SDS with β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma Aldrich) followed by immediate boiling at 95°C for 2 min before storage at −80°C. Samples were run on SDS-PAGE electrophoresis, wet-transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (BioRad) that were then blocked as described [48]. After blocking, membranes were incubated with 1:1 000 dilution (5% bovine serum albumin in TBS-T) of primary antibodies against cleaved (Cell Signaling), whole IL-1β (Santa Cruz), caspase-1 (Cell Signaling), NLRP3 (Adipogen), ASC (Adipogen) or β-actin (Cell Signaling; used at 1:2 000 dilution) overnight at 4°C. After 3 washes, the blots were probed with anti-mouse goat IgG (LI-COR) or anti-rabbit donkey IgG (LI-COR) secondary antibodies (1:10 000 in TBS-T), as indicated, conjugated with fluorescent dyes (IRDye 680 or IRDye 800 CW; LI-COR Biosciences), for 1 hour at room temperature. Blots were imaged using the LI-COR Odyssey infrared imaging system as described [48].

Statistical analyses

A two-sided Mann-Whitney U Test was used for all group comparisons, assuming a non-parametric distribution. In univariate analyses of clinical factors associated with caspase-1 activity, we included 21 subjects with a minimum of 6 subjects per group (clinical characteristics of subjects have been provided in Supporting Information table 1) for binary variables (i.e. exposure to antenatal corticosteroids, multiple gestation, histological chorioamnionitis) to provide 80% power (p<0.05). For multivariate analyses of factors influencing caspase-1 activity, adjustment for the following covariables: presence of maternal or fetal chorioamnionitis stage one or greater, gestational age was performed using SPSS Statistics 20 (IBM, CA), with ‘caspase-1 activity’ (%-positive cells) as the dependent variable.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the families who participated, to Nadine Lusney, Kristi Finlay Alice van Zanten and Nicole Farrell, as well as the BC Women’s Hospital delivery room staff and members of the Research in Advanced Fetal diagnosis and Therapy (RAFT) Group for their continuing support with recruitment of human research subjects for this study. This research was funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research grant (MOP-110938 to PML). AAS was supported by a Child & Family Research Institute (CFRI) Graduate Studentship. PML is supported by a Clinician-Scientist Award from the CFRI and a Career Investigator Award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (MSFHR). SET holds the Aubrey J. Tingle Professorship in Pediatric Immunology and a Clinical Research Scholar Award from the MSFHR. LMS holds a Biomedical Research Scholar Award from the MSFHR.

Abbreviations

- ASC

Apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD

- FLICA

Fluorescent-Labeled Inhibitor of Caspase-1 Activation

- FMO

Fluorescence minus one

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no financial or commercial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Sharma AA, Jen R, Butler A, Lavoie PM. The developing human preterm neonatal immune system: A case for more research in this area. Clin Immunol. 2012;145:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dinarello CA. Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin-1 family. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:519–550. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zheng H, Fletcher D, Kozak W, Jiang M, Hofmann KJ, Conn CA, Soszynski D, Grabiec C, Trumbauer ME, Shaw A, et al. Resistance to fever induction and impaired acute-phase response in interleukin-1 beta-deficient mice. Immunity. 1995;3:9–19. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller LS, Pietras EM, Uricchio LH, Hirano K, Rao S, Lin H, O’Connell RM, Iwakura Y, Cheung AL, Cheng G, Modlin RL. Inflammasome-mediated production of IL-1beta is required for neutrophil recruitment against Staphylococcus aureus in vivo. J Immunol. 2007;179:6933–6942. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vonk AG, Netea MG, van Krieken JH, Iwakura Y, van der Meer JW, Kullberg BJ. Endogenous interleukin (IL)-1 alpha and IL-1 beta are crucial for host defense against disseminated candidiasis. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:1419–1426. doi: 10.1086/503363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oguri S, Motegi K, Iwakura Y, Endo Y. Primary role of interleukin-1 alpha and interleukin-1 beta in lipopolysaccharide-induced hypoglycemia in mice. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2002;9:1307–1312. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.9.6.1307-1312.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Favrais G, van de Looij Y, Fleiss B, Ramanantsoa N, Bonnin P, Stoltenburg-Didinger G, Lacaud A, Saliba E, Dammann O, Gallego J, Sizonenko S, Hagberg H, Lelievre V, Gressens P. Systemic inflammation disrupts the developmental program of white matter. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:550–565. doi: 10.1002/ana.22489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gotz F, Dorner G, Malz U, Rohde W, Stahl F, Poppe I, Schulze M, Plagemann A. Short- and long-term effects of perinatal interleukin-1 beta-application in rats. Neuroendocrinology. 1993;58:344–351. doi: 10.1159/000126560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen JN, Herzyk DJ, Allen ED, Wewers MD. Human whole blood interleukin-1-beta production: kinetics, cell source, and comparison with TNF-alpha. J Lab Clin Med. 1992;119:538–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsi ED, Remick DG. Monocytes are the major producers of interleukin-1 beta in an ex vivo model of local cytokine production. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1995;15:89–94. doi: 10.1089/jir.1995.15.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frankenberger M, Sternsdorf T, Pechumer H, Pforte A, Ziegler-Heitbrock HW. Differential cytokine expression in human blood monocyte subpopulations: a polymerase chain reaction analysis. Blood. 1996;87:373–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Passlick B, Flieger D, Ziegler-Heitbrock HW. Identification and characterization of a novel monocyte subpopulation in human peripheral blood. Blood. 1989;74:2527–2534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ziegler-Heitbrock HW, Strobel M, Kieper D, Fingerle G, Schlunck T, Petersmann I, Ellwart J, Blumenstein M, Haas JG. Differential expression of cytokines in human blood monocyte subpopulations. Blood. 1992;79:503–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ancuta P, Liu KY, Misra V, Wacleche VS, Gosselin A, Zhou X, Gabuzda D. Transcriptional profiling reveals developmental relationship and distinct biological functions of CD16+ and CD16- monocyte subsets. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:403. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fingerle G, Pforte A, Passlick B, Blumenstein M, Strobel M, Ziegler-Heitbrock HW. The novel subset of CD14+/CD16+ blood monocytes is expanded in sepsis patients. Blood. 1993;82:3170–3176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong KL, Yeap WH, Tai JJ, Ong SM, Dang TM, Wong SC. The three human monocyte subsets: implications for health and disease. Immunol Res. 2012;53:41–57. doi: 10.1007/s12026-012-8297-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mariathasan S, Monack DM. Inflammasome adaptors and sensors: intracellular regulators of infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:31–40. doi: 10.1038/nri1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sutterwala FS, Ogura Y, Szczepanik M, Lara-Tejero M, Lichtenberger GS, Grant EP, Bertin J, Coyle AJ, Galan JE, Askenase PW, Flavell RA. Critical role for NALP3/CIAS1/Cryopyrin in innate and adaptive immunity through its regulation of caspase-1. Immunity. 2006;24:317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strunk T, Prosser A, Levy O, Philbin V, Simmer K, Doherty D, Charles A, Richmond P, Burgner D, Currie A. Responsiveness of human monocytes to the commensal bacterium Staphylococcus epidermidis develops late in gestation. Pediatr Res. 2012;72:10–18. doi: 10.1038/pr.2012.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dinarello CA, Shparber M, Kent EF, Jr, Wolff SM. Production of leukocytic pyrogen from phagocytes of neonates. J Infect Dis. 1981;144:337–343. doi: 10.1093/infdis/144.4.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Philbin VJ, Dowling DJ, Gallington LC, Cortes G, Tan Z, Suter EE, Chi KW, Shuckett A, Stoler-Barak L, Tomai M, Miller RL, Mansfield K, Levy O. Imidazoquinoline Toll-like receptor 8 agonists activate human newborn monocytes and dendritic cells through adenosine-refractory and caspase-1-dependent pathways. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:195–204. e199. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Appleby LJ, Nausch N, Midzi N, Mduluza T, Allen JE, Mutapi F. Sources of heterogeneity in human monocyte subsets. Immunol Lett. 2013;152:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Munoz-Planillo R, Kuffa P, Martinez-Colon G, Smith BL, Rajendiran TM, Nunez G. K(+) efflux is the common trigger of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by bacterial toxins and particulate matter. Immunity. 2013;38:1142–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehta VB, Hart J, Wewers MD. ATP-stimulated release of interleukin (IL)-1beta and IL-18 requires priming by lipopolysaccharide and is independent of caspase-1 cleavage. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:3820–3826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006814200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sadeghi K, Berger A, Langgartner M, Prusa AR, Hayde M, Herkner K, Pollak A, Spittler A, Forster-Waldl E. Immaturity of infection control in preterm and term newborns is associated with impaired toll-like receptor signaling. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:296–302. doi: 10.1086/509892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sohlberg E, Saghafian-Hedengren S, Bremme K, Sverremark-Ekstrom E. Cord blood monocyte subsets are similar to adult and show potent peptidoglycan-stimulated cytokine responses. Immunology. 2011;133:41–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03407.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Currie AJ, Curtis S, Strunk T, Riley K, Liyanage K, Prescott S, Doherty D, Simmer K, Richmond P, Burgner D. Preterm infants have deficient monocyte and lymphocyte cytokine responses to group B streptococcus. Infect Immun. 2011;79:1588–1596. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00535-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levy E, Xanthou G, Petrakou E, Zacharioudaki V, Tsatsanis C, Fotopoulos S, Xanthou M. Distinct roles of TLR4 and CD14 in LPS-induced inflammatory responses of neonates. Pediatr Res. 2009;66:179–184. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181a9f41b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rallabhandi P, Bell J, Boukhvalova MS, Medvedev A, Lorenz E, Arditi M, Hemming VG, Blanco JC, Segal DM, Vogel SN. Analysis of TLR4 polymorphic variants: new insights into TLR4/MD-2/CD14 stoichiometry, structure, and signaling. J Immunol. 2006;177:322–332. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schindler R, Clark BD, Dinarello CA. Dissociation between interleukin-1 beta mRNA and protein synthesis in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:10232–10237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herzyk DJ, Allen JN, Marsh CB, Wewers MD. Macrophage and monocyte IL-1 beta regulation differs at multiple sites. Messenger RNA expression, translation, and post- translational processing. J Immunol. 1992;149:3052–3058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kallapur SG, Nitsos I, Moss TJ, Polglase GR, Pillow JJ, Cheah FC, Kramer BW, Newnham JP, Ikegami M, Jobe AH. IL-1 mediates pulmonary and systemic inflammatory responses to chorioamnionitis induced by lipopolysaccharide. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:955–961. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200811-1728OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huttenlocher A, Frieden IJ, Emery H. Neonatal onset multisystem inflammatory disease. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:1171–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou R, Tardivel A, Thorens B, Choi I, Tschopp J. Thioredoxin-interacting protein links oxidative stress to inflammasome activation. Nat Immunol. 2009;11:136–140. doi: 10.1038/ni.1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuida K, Lippke JA, Ku G, Harding MW, Livingston DJ, Su MS, Flavell RA. Altered cytokine export and apoptosis in mice deficient in interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme. Science. 1995;267:2000–2003. doi: 10.1126/science.7535475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li P, Allen H, Banerjee S, Franklin S, Herzog L, Johnston C, McDowell J, Paskind M, Rodman L, Salfeld J, et al. Mice deficient in IL-1 beta-converting enzyme are defective in production of mature IL-1 beta and resistant to endotoxic shock. Cell. 1995;80:401–411. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90490-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maelfait J, Vercammen E, Janssens S, Schotte P, Haegman M, Magez S, Beyaert R. Stimulation of Toll-like receptor 3 and 4 induces interleukin-1beta maturation by caspase-8. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1967–1973. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gross O, Poeck H, Bscheider M, Dostert C, Hannesschlager N, Endres S, Hartmann G, Tardivel A, Schweighoffer E, Tybulewicz V, Mocsai A, Tschopp J, Ruland J. Syk kinase signalling couples to the Nlrp3 inflammasome for anti-fungal host defence. Nature. 2009;459:433–436. doi: 10.1038/nature07965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kono H, Orlowski GM, Patel Z, Rock KL. The IL-1-dependent sterile inflammatory response has a substantial caspase-1-independent component that requires cathepsin C. J Immunol. 2012;189:3734–3740. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kunkel SL, Chensue SW, Phan SH. Prostaglandins as endogenous mediators of interleukin 1 production. J Immunol. 1986;136:186–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371:75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shi CS, Shenderov K, Huang NN, Kabat J, Abu-Asab M, Fitzgerald KA, Sher A, Kehrl JH. Activation of autophagy by inflammatory signals limits IL-1beta production by targeting ubiquitinated inflammasomes for destruction. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:255–263. doi: 10.1038/ni.2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harris J, Hartman M, Roche C, Zeng SG, O’Shea A, Sharp FA, Lambe EM, Creagh EM, Golenbock DT, Tschopp J, Kornfeld H, Fitzgerald KA, Lavelle EC. Autophagy controls IL-1beta secretion by targeting pro-IL-1beta for degradation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:9587–9597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.202911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kramer BW, Jobe AH. The clever fetus: responding to inflammation to minimize lung injury. Biol Neonate. 2005;88:202–207. doi: 10.1159/000087583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bird S, Zou J, Wang T, Munday B, Cunningham C, Secombes CJ. Evolution of interleukin-1beta. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002;13:483–502. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(02)00028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Redline RW, Faye-Petersen O, Heller D, Qureshi F, Savell V, Vogler C. Amniotic infection syndrome: nosology and reproducibility of placental reaction patterns. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2003;6:435–448. doi: 10.1007/s10024-003-7070-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lavoie PM, Huang Q, Jolette E, Whalen M, Nuyt AM, Audibert F, Speert DP, Lacaze-Masmonteil T, Soudeyns H, Kollmann TR. Profound lack of interleukin (IL)-12/IL-23p40 in neonates born early in gestation is associated with an increased risk of sepsis. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:1754–1763. doi: 10.1086/657143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tang A, Sharma A, Jen R, Hirschfeld AF, Chilvers MA, Lavoie PM, Turvey SE. Inflammasome-mediated IL-1beta production in humans with cystic fibrosis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37689. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.