Abstract

Background

Neural crest cells play an important role in craniofacial morphogenesis and many other developmental processes. The formation of neural crest cells (NCCs) in vivo is a highly dynamic process and remains to be fully understood.

Results

To investigate the spatiotemporal patterning of NCCs in vivo, we have generated Sox10ERT2CreERT2 (SECE) mice, a transgenic line driving inducible Cre expression in NCCs. Inducing Cre activity at different stages triggered reporter expression in distinct NCC populations in SECE; R26R mice. By optimizing the timing and dosage of tamoxifen administration, we controlled Cre expression specifically in cranial NCCs. Using this approach, we demonstrate an important role for PDGFRα in cranial NCCs mitosis within the mandibular processes. Further reducing Cre activity within the cranial NCCs of SECE; R26R embryos revealed that SECE labels preferentially progenitors of medial nasal process (MNP) rather than the lateral nasal process (LNP), before their formation from the frontonasal prominence (FNP).

Conclusions

Our results indicate that NCCs are formed sequentially from rostral to caudal regions along the neural tube. These findings also suggest that NCCs within the FNP become specified regionally and genetically before they divide into MNP and LNP.

Keywords: Cre recombinase, lineage tracing, neural crest, craniofacial development

Introduction

Neural crest cells (NCCs) are a transient cell population unique to vertebrates characterized by their extensive migration and multipotent properties (Le Douarin and Kalcheim, 1999; Hall, 2009). In developing embryos, NCCs arise at the boundary of the neural plate and the non-neural ectoderm. Subsequently, these ectodermal cells delaminate and undergo an epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Following extensive migration through the embryo, they give rise to a broad spectrum of cell types, including neurons, smooth muscle cells, adipocytes, melanocytes, fibroblasts, chondrocytes, osteoblasts and osteocytes (Bronner and LeDouarin, 2012). Abnormalities of neural crest derived cells are implicated in a variety of diseases ranging from birth defects to cancer (Etchevers et al., 2006).

NCCs arise at different axial levels, and can be divided into cranial, cardiac, trunk or enteric subgroups. These subtypes exhibit both unifying and distinct properties. For example, they share similar guidance cues during migration, and migrate in segmental patterns (Gammill and Roffers-Agarwal, 2010; Kulesa et al., 2010; Kulesa and Gammill, 2010; Theveneau and Mayor, 2012). They also show transient expression of a number of genetic markers including Twist1, Snail, Tcfap2a, FoxD3, Wnt1 and Sox10 (Simoes-Costa and Bronner, 2015). Generation of Cre-based lineage tracers, such as Wnt1Cre, Wnt1Cre2, Mef2cCre and Sox10Cre, allows fate mapping of NCCs and has significantly advanced our understanding of NCC development (Danielian et al., 1998; Chai et al., 2000; Jiang et al., 2000; Matsuoka et al., 2005; Stine et al., 2009; Simon et al., 2012; Lewis et al., 2013; McKenzie et al., 2014; Aoto et al., 2015). On the other hand, NCCs at different axial levels have distinct potencies during embryo development. For instance, only the cranial NCCs, but not cardiac or trunk NCCs, are capable of developing into cartilage, bone and connective tissues (Noden, 1978; Noden, 1988; Le Douarin and Kalcheim, 1999).

The spatiotemporal distribution of NCCs in the developing embryos has been a long-standing interest of developmental biologists, previous efforts have relied on focal DiI labeling in combination with ex-vivo or ex-utero embryo culture (Serbedzija et al., 1992; Osumi-Yamashita et al., 1994). These studies have shown that in mouse embryos, the destination and timing of NCC migration depend on their origins along the axial level.

During mouse craniofacial morphogenesis, the primitive face is composed of five primordia: the frontonasal prominence (FNP), two paired maxillary processes and two paired mandibular processes (Helms et al., 2005; Dixon et al., 2011). These primordia are populated predominantly by cranial NCCs, which surround a mesodermal core and are covered by an epithelium. By E10.5, thickening of the FNP ectoderm occurs bilaterally at the ventrolateral level to form the nasal placodes. The FNP is then further divided into the medial nasal process (MNP) and lateral nasal processes (LNP) around the nasal placodes (Jiang et al., 2006). It is unclear if the FNP cells are regionally specified or randomly distributed before this division.

Here we present a genetic tool that enables visualization of NCC formation and patterning in vivo. Sox10ERT2CreERT2 (SECE) transgenic mice drive inducible Cre recombinase expression under the control of the Sox10 MCS4 distal enhancer (Matsuda and Cepko, 2007; Stine et al., 2009). The spatiotemporal formation of NCCs was examined in mouse embryos by using this strain in combination with the R26R Cre reporter (Soriano, 1999). By optimizing the dosage and timing of tamoxifen administration, only cranial NCCs could be labeled in SECE; R26R embryos, indicating that this line can be used to study gene function in cranial NCCs. Platelet growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRα) is essential for craniofacial morphogenesis (Soriano, 1997; Tallquist and Soriano, 2003; He and Soriano, 2013). Our results with SECE mediated inactivation of PDGFRα specifically in cranial NCCs revealed that PDGFRα is not only critical for midfacial morphogenesis, but is also required for mandible development. Further reduction of tamoxifen dosage in SECE; R26R embryos preferentially labels MNP cells, suggesting that the progenitors of the MNP and LNP are specified early, before FNP division.

Results

Generation of SECE transgenic mice

To examine the tempo-spatial pattern of NCCs and trace their destination in mouse embryos, we generated Sox10ERT2CreERT2 (SECE) transgenic mice. The DNA fragment used for pronuclear injection includes the Sox10 MCS4 enhancer/c-Fos minimal promoter, the Cre coding sequences flanked by two ERT2 domains, and the rabbit globin polyA (pA) sequences (Fig 1A) (Matsuda and Cepko, 2007; Antonellis et al., 2008; Stine et al., 2009). Nine founders carrying the transgene were identified by PCR genotyping. To examine Cre activity, the transgenic mice were crossed to R26R Cre reporter mice (Soriano, 1999), which received one-time tamoxifen administration (100 μg/g body weight by I.P.) at 7.5 days post coitum (dpc). X-Gal staining of E11.5 embryos showed that two transgenic lines exhibited similar Cre activity in NCCs and their derivatives (Fig 1), consistent with fate mapping of NCCs using S4F:Cre mice (Stine et al., 2009). All subsequent studies were carried out using one of these lines (SECE17).

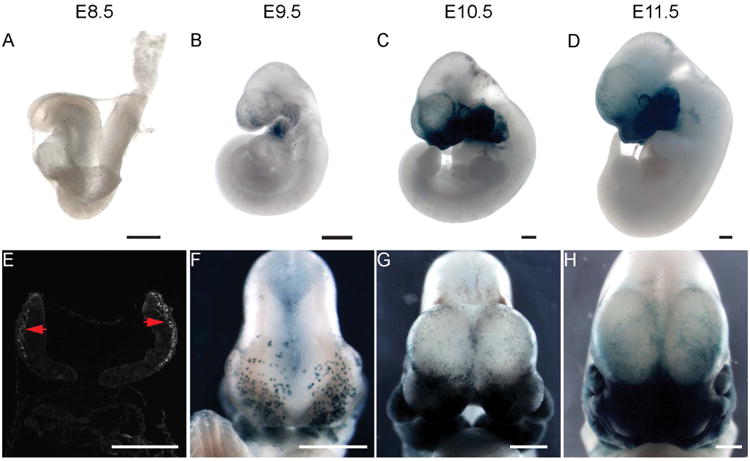

Figure 1. SECE labels distinct NCC populations in the developing mouse embryos.

(A) Design of SECE transgenic mice. The construct used for pronuclei injection includes the Sox10 MCS4 enhancer, c-fos minimal promoter and Cre coding sequence flanked by two ERT2 domains followed by the rabbit globin poly-adenylation sequence (pA). (B-D″) Lateral view (B, C, D), ventral view (B′, C′, D′) and dorsal view (B″, C″, D″) of E11.5 embryos showing LacZ reporter expression detected in tissues derived from distinct NCC populations. (B-B″) Administering tamoxifen at E7.5 induces Cre expression in tissues derived from some trunk NCCs and most cranial NCCs in E11.5 embryos. These include neural cranium and facial mesenchyme (B, blank arrow), outflow tract (B, pink arrow), sympathetic chains (B, black arrow) and DRG (B, black arrow head). (C-C″) When tamoxifen is administered at E8.5, LacZ reporter expression persists in the midbrain and DRG. (D-D″) Administering tamoxifen at E10.5 labels the anterior ventricle of the forebrain, midbrain and hindbrain. At the trunk level, LacZ expression is restricted to the neural tube and shifts to the caudal region.

SECE enables tracing distinct cell populations of Sox10 progeny

Previous studies have documented the dynamic expression pattern of Sox10 mRNA in multiple NCC derivatives and glial cells of mouse embryos (Kuhlbrodt et al., 1998; Pusch et al., 1998; Southard-Smith et al., 1998). To fate map these distinct NCC populations, Cre expression was induced in SECE; R26R embryos at 6.5, 7.5, 8.5 or 10.5 dpc, using a single I.P. injection of tamoxifen (100 μg/g body weight) (Fig 1 and 2). Tamoxifen administration at 6.5 dpc did not label any cells in E11.5 SECE; R26R embryos (data not shown, n=12). When tamoxifen was administered at 7.5 dpc, lacZ expression was detected in cells in the facial mesenchyme, neural cranium, roof of the midbrain and fourth ventricle and foregut (Fig 1B, and B′) (n=7). These tissues represent typical NCC derivatives, which have been characterized using Wnt1Cre, Wnt1Cre2 and S4F:Cre lineage tracing (Chai et al., 2000; Jiang et al., 2000; Stine et al., 2009; Lewis et al., 2013). Notably, the LacZ expression pattern in SECE; R26R embryos was identical to that in S4F:Cre; R26R at the cranial level, and few cells were labeled in cranial NCC derivatives when Cre expression was induced at later stages (Fig 1B-D′; Fig 2A-C). These results confirmed that induction of SECE activity following tamoxifen administration at 7.5 dpc labeled most cranial NCCs. In contrast, neuronal cells at the midbrain roof were labeled in all embryos receiving tamoxifen administration at 7.5, 8.5 or 10.5 dpc, and the reporter expression domain expanded to a more rostral region following the timing of Cre induction, indicating that Sox10 expression persisted in this region (Fig 1B-D′). At the trunk level, tamoxifen administration at 7.5 dpc resulted in labeling of the sciatic nerve, dorsal root ganglia (DRG) and the sympathetic chain, while LacZ expression was reduced rostral to caudal along the neural tube (Fig 1B-B″; Fig 2A′-A‴). From E7.5 through E10.5, following the timing of tamoxifen administration, labeled DRG domains gradually shifted to a more caudal region (Fig 2A′, B′, B″ and C‴), recapitulating the gradient formation of peripheral neural system. In line with endogenous Sox10 mRNA expression pattern, we detected LacZ expression in the cells within the ventral neural tube (Fig 2A′, B′, B″ and C‴), which likely represent oligodendrocyte precursors. Additionally, cells surrounding the neural tube were also labeled in SECE; R26R embryos (Fig 2C′ and C″), indicating the progenitors of these cells were formed within this time frame later than cranial NCCs and DRGs.

Figure 2. LacZ reporter expression is detected in the section of SECE; R26R embryos labeled with differential NCC populations.

E11.5 embryos were stained and sectioned after receiving tamoxifen administration at E7.5 (A- A‴), E8.5 (B- B‴) or E10.5 (C- C‴). (A- A‴) Administering tamoxifen at E7.5 triggers intensive reporter expression in the cranial mesenchymal cells (blank arrow in A) and meningeal cells (arrow in A), and DRG (arrow in A′) and ventral region of rostral neural tube (pink arrow in A′). Only few cells are labeled in the caudal DRG cells and no reporter expression is detected in the caudal neural tube. (B- B‴) When tamoxifen is administered at E8.5, LacZ reporter expression is induced in the DRG cells along neural tube in the rostral and more caudal level (arrows in B′ and B″), as well as in the neural tube of these regions (B′ and B″), but not at the most caudal level (B‴). (C- C‴) Administering tamoxifen at E10.5 leads to reporter expression in the cells surrounding the neural tube in the rostral region (red arrows in C′ and C″). At a more caudal level, reporter expression is detected within the neural tube (green arrow in C‴).

Tracing cranial NCCs in SECE; R26R embryos

One advantage of the CreERT2 system is that recombination efficiency depends on the dosage of tamoxifen (Hayashi et al., 2002). Interestingly, we found that adjusting the tamoxifen dose not only controlled reporter expression levels, but also affected its pattern. When pregnant mice were administered with tamoxifen at 25 μg/g body weight at 7.5 dpc, SECE; R26R embryos expressed reporter gene specifically in the cranial NCC derivatives (Fig 3). This feature facilitates tracing cranial NCCs in the developing embryos. To this end, SECE; R26R embryos were dissected at twenty-four hour intervals following tamoxifen injection at 7.5 dpc. At E8.5, only few NCCs were labeled in the first branchial arch (n=12) (Fig 3A). Immunostaining however shows that Sox10 is expressed extensively in the emigrating cranial NCCs (Fig 3E). The disparity of these results suggests a delay between the timing of tamoxifen injection and detectable recombination at the R26R locus. In E9.5 SECE; R26R embryos, LacZ expression was detected in multiple cells in the branchial arches and neurocranium progenitor cells covering the forebrain (Fig 3B and F). LacZ expressing cells became increasingly abundant in the facial mesenchyme and neurocranium covering the forebrain by E10.5 (Fig 3E and G) and E11.5 (Fig 3D and H). We also found that administration of 25 ug/g tamoxifen led to lethality of around 20% embryos at E16.5 (8 out of 41 embryos from 6 litters were pale or arrested at an earlier stage when dissected at E16.5), while injection of tamoxifen at 10 ug/g did not cause embryo lethality at this stage (n=32 from 4 litters).

Figure 3. SECE specifically labels cranial NCCs with adjusted tamoxifen dosage.

(A-D) Lateral view of SECE; R26R embryos from E8.5 through E11.5, using 25 μg/g body weight tamoxifen administration at E7.5. LacZ reporter expression is restricted to the cranial mesenchyme of the embryos at different stages. (E) Section immunofluorescence staining reveals intensive expression of Sox10 protein in cranial mesenchyme at E8.5. (F-H) Frontal view of SECE; R26R embryos from E9.5 through E11.5. Scale bar= 500 μm.

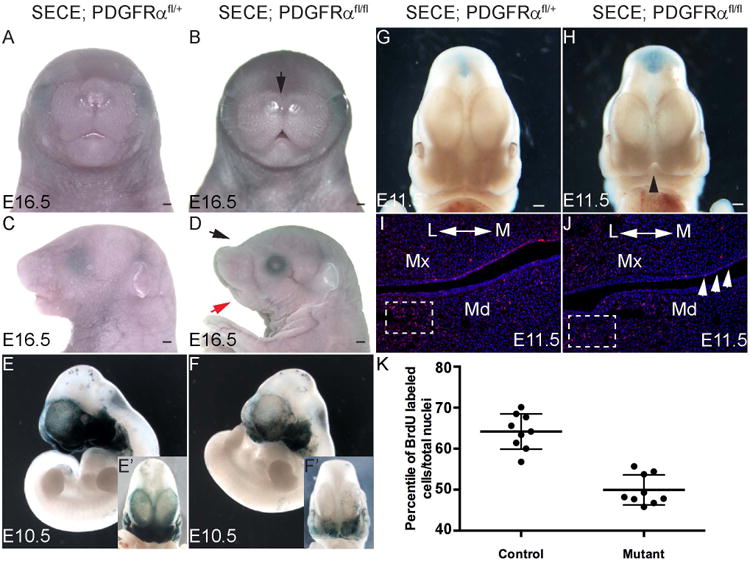

The restricted expression pattern of Cre enabled us to analyze gene function specifically in cranial NCCs. PDGFRα is essential for NCC development (Soriano, 1997; Tallquist and Soriano, 2003; He and Soriano, 2013). To gain further insight into its role specifically in cranial NCCs, we generated SECE; PDGFRαfl/fl mice, and controlled Cre activity specifically in the cranial NCCs. The resulting SECE; PDGFRαfl/fl embryos exhibited a frontonasal dysplasia phenotype and hypoplastic mandible (Fig 4A, B, C and D). Lineage tracing results showed fewer NCCs labeled in the craniofacial tissues of the conditional knockout embryos at E10.5 (Fig 4E, E′, F and F′). We traced the craniofacial phenotypes in SECE; PDGFRαfl/fl mice back to E11.5. At this stage, the MNP had met in the midline in wild type embryos. In mutant embryos, however, a distinguishable gap still existed (Fig 4G and H). BrdU assay revealed that fewer MNP mesenchymal cells were undergoing proliferation in mutant embryos than in littermate controls (data not shown). This was consistent with our previous observations that PDGFRα is required to maintain normal proliferation of MNP mesenchymal cells (He and Soriano, 2013). In addition, inactivating PDGFRα also led to decreased numbers of BrdU-labeled cells in the developing mandibular mesenchyme (Fig 4I and J). In the lateral mandibular mesenchyme, 64.2% ± 4.3% cells were labeled in control embryos (n=9), whereas only 49.9% ± 3.7% cells were labeled in mutant embryos (n=9, p<0.01) (Fig 4K). This result was in line with previous findings that PDGFRα is expressed in the mesenchyme and is important to maintain the mitosis of cranial NCCs (He and Soriano, 2013; Fantauzzo and Soriano, 2014). Interestingly, proliferation of mutant epithelial cells was also decreased (Fig 4J), suggesting that PDGFRα has a role in the epithelial-mesenchymal interaction during craniofacial morphogenesis.

Figure 4. PDGFRα is essential to maintain cell mitosis in the mandibular process.

(A-D) Frontal and lateral view of SECE; PDGFRαfl/+(A, C) and SECE; PDGFRαfl/f (B, D) embryos at E16.5. SECE; PDGFRαfl/fl embryo exhibits medial nasal hypoplasia (black arrows in B and D) and hypoplastic mandible (red arrow in D). (E, F) Expression of LacZ reporter in SECE; PDGFRαfl/+; R26R+/- (E), SECE; PDGFRαfl/fl; R26R+/- (F) embryos at E10.5. (E′, F′) Frontal views of PDGFRαfl/+; R26R+/- and SECE; PDGFRαfl/fl; R26R+/- embryos at E10.5 (G, H) Frontal view of SECE; PDGFRαfl/+ (G) and SECE; PDGFRαfl/fl (H) embryo at E11.5. Black arrow head refers to the medial nasal clefting (H). (I-K) Frontal section of BrdU labeled SECE; PDGFRαfl/+; R26R+/- (I), SECE; PDGFRαfl/fl; R26R+/- (J) embryos at E11.5. BrdU labeled cells are stained with red fluorescence, and nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Blank arrows refer to the oral epithelia cells in mutant embryo. (K) Scatter plots show that cell proliferation in the defined mandible mesenchyme is significantly decreased in mutant embryos (n=9, p<0.01). All embryos received tamoxifen administration at 25 μg/g body weight at E7.5. Scale bar= 500 μm. L, lateral; M, medial; Md, mandible; Mx, maxilla.

When the dose of administered tamoxifen was further reduced to 10 μg/g body weight at 7.5 dpc, significantly fewer cells were labeled. In the E11.5 SECE; R26R embryos, reporter expression was detected only in a small group of cells in the mesenchyme of the frontal cranium, maxilla, mandible and MNP (Fig 5). Although both the MNP and LNP originate from the FNP, LacZ-expressing cells were distributed predominantly in the MNP (Fig 5A) (n=14). Lineage tracing in E10.5 SECE; R26R embryos reveals a similar expression pattern (Fig 5B, B′) (n=12). To our surprise, no LacZ expression was detected in the FNP region at E9.5 (Fig 5C, C′)(n=10). In proximity to the FNP, only a few cells in the mesenchyme beneath the developing retina were labeled, indicating these are the MNP progenitors identified at E10.5 and E11.5. Such an expression pattern of MNP progenitors has been identified in chicken embryos (Lee et al., 2004). Together these results suggest an active remodeling of MNP at early stages during facial morphogenesis, and a conservation of this mechanism from avians to mammals.

Figure 5. SECE preferably labels MNP progenitors with administration of minimal dosage of tamoxifen.

(A-C) LacZ reporter expression in SECE; R26R+/- embryos when tamoxifen is administered at 10 μg/g body weight by I.P. injection at E7.5. (A) In E11.5 embryos, reporter expression is detected in the neural cranium (black arrow), the mandible (blank arrow) and the medial nasal process (red arrow). (B) At E10.5, LacZ reporter is expressed in the neural cranium (black arrow), the mandible (blank arrow) and the medial nasal process (red arrow). (B′) Magnification of the craniofacial region defined in B. (C) E9.5 embryo expresses LacZ in progenitors of the neural cranium (black arrow), the mandible (blank arrow) and cells beneath the developing retina (red arrow). (C′) Magnification of craniofacial region defined in C.

Discussion

SECE is a useful tool to study gene function in distinct NCC populations

NCCs comprise transient and multipotent cells formed at different stages and of distinct origins. A number of genetic tools, such as Wnt1Cre (Danielian et al., 1998), Wnt1Cre2 (Lewis et al., 2013), Sox10Cre (Matsuoka et al., 2005), S4F:Cre (Stine et al., 2009), Sox10-CreERT2(McKenzie et al., 2014), Sox10-iCreERT2 (Simon et al., 2012), Mef2cCre (Aoto et al., 2015), and Ht-PA-Cre (Pietri et al., 2003) have been generated to drive Cre expression in pre-migratory and post-migratory neural crest cells, facilitating examination of gene function in multiple processes. Of the transgenic lines generated with Sox10 locus, Sox10Cre (Matsuoka et al., 2005) and Sox10-CreERT2 (McKenzie et al., 2014) utilized the same PAC clone spanning 170kb around Sox10 locus, and Sox10-iCreERT2 (Simon et al., 2012) used a ∼140kb BAC clone. Lineage tracing showed that all three lines label oligodendrocytes, peripheral nervous system, pericytes, melanocytes and other neural crest cells derivatives in adult and embryos. S4F:Cre (Stine et al., 2009) was generated using a conserved distal Sox10 enhancer MCS4, which drives Cre expression specifically in oligodendrocytes and neural crest derivatives in embryos. In the present study, we generated SECE mice using the same MCS4 enhancer to analyze neural crest cell formation in developing mouse embryos. We show that SECE mice are able to drive Cre expression in distinct populations of NCCs along the rostral-caudal axis (Fig 1 and Fig 2). We have further characterized the dosage and timing for tamoxifen administration required to induce Cre expression in specific group of NCCs. ERT2-Cre-ERT2 exhibits virtually no background activity in the absence of tamoxifen stimulation, as observed in the present study and the original report (Matsuda and Cepko 2007). The tighter regulation of Cre activity by ERT2-Cre-ERT2 could be attributed to increased association with Hsp90 preventing the translocation of the fusion protein to the nucleus and recombination, or reduced activity of ERT2-Cre-ERT2 (Matsuda and Cepko 2007).

Spatiotemporal patterning of pre-migratory NCCs in mouse embryos

NCCs give rise to the vast majority of craniofacial mesenchymal cells, which further develop into multiple craniofacial tissues and organs (Chai et al., 2000). A long-standing question has been how pre-migratory NCCs are patterned and how they migrate to different destinations. In previous studies, NCCs were labeled with vital dyes or DiI and the destination of the marked cells was traced in cultured embryos (Serbedzija et al., 1992; Osumi-Yamashita et al., 1994). These studies provided a fate map for NCCs originating from different regions. NCCs from the forebrain and rostral midbrain region migrate towards the frontonasal prominence while those from the caudal midbrain and hindbrain regions migrate into the pharyngeal arches. Experimental results from these studies also indicated that migration into the frontonasal prominences ceases earlier than that towards pharyngeal arches (Serbedzija et al., 1992; Osumi-Yamashita et al., 1994). While these results provided valuable information, two major limitations have hindered further exploration of NCCs patterning in mouse embryos. First, vital dye or DiI labeling cannot be restricted to only NCCs. The lineage tracing result might therefore be hard to interpret, considering the intensive mixing of other cell populations such as mesoderm during craniofacial morphogenesis. Interpreting the results becomes further problematic considering that non-NCCs also undergo active migration trailing the NCCs (Breau et al., 2008). The second caveat lies in the limitation of mouse embryo culture, which cannot exceed twenty-four hours. Application of ex utero surgery can extend the development of labeled embryos to a certain extent, but cannot completely circumvent this limitation (Serbedzija et al., 1992; Ngo-Muller and Muneoka, 2010). Neural crest Cre transgenic mice, such as Wnt1Cre (Danielian et al., 1998), enable permanent labeling of neural crest derived cells in vivo. The use of SECE mice enables permanent labeling of specific NCC populations in vivo, once Cre expression is induced in embryos. Using this tool, we have been able to validate previous findings in vivo, showing that NCCs are sequentially formed in a rostral to caudal direction along the neural tube (Fig 1).

Specification of MNP and LNP progenitors

During mouse embryogenesis, the FNP divides into the MNP and LNP at E10.5, but it remains unclear when the progenitors of the MNP and LNP become specified. In this study, we show that administration of a minimal dose of tamoxifen (10 μg/g body weight) allows labeling of MNP progenitors in mouse embryos (Fig 5), and a higher dose of tamoxifen (25 μg/g body weight) labels both MNP and LNP cells (Fig 3). These results suggest that these progenitor cells are pre-patterned instead of mixed within the cranial mesenchyme before division of the FNP occurs. We have further analyzed gene expression profiles from the MNP and LNP using the microarray data from the Facebase consortium (https://www.facebase.org/) (Hochheiser et al., 2011). Data analysis reveals that 31 genes were enriched in the MNP and 17 genes were enriched in the LNP (Table 1). Transcripts of two close related homeobox transcription factors, Alx1 and Alx3, are distributed in each group: Alx1 expression is enriched in the LNP, while Alx3 expression is restricted to the MNP. Recently whole mount in situ hybridization data have been published, showing that at E9.5, Alx1 and Alx3 are expressed in different compartments in the cranial mesenchyme before FNP division (Brunskill et al., 2014). These results, together with our lineage tracing data, indicate that the MNP and LNP are specified regionally before FNP division. Interestingly, DiI labeling studies using chicken embryos indicate that the progenitors of LNP and frontonasal mass fusion zone (the avian counterpart of the MNP) originate from different regions, suggesting this mechanism is conserved across different phila (Lee et al., 2004).

Table 1. Genes exhibiting differential expression level in the developing MNP or LNP.

Symbols and description of genes with enriched expression in MNP and LNP. Microarray data were obtained from Facebase consortium, in the category of gene expression microarray - mouse E10.5 medial-nasal process (accession number FB00000103) and mouse E10.5 lateral-nasal process (accession number FB00000105). The tissues used for RNA preparation and Affymetrix microarray assay were obtained using laser capture microdissection from MNP or LNP of E10.5 mouse embryos. Gene expression was analyzed using Affymetrix Mouse gene 1.0 ST array. Expression data was compared between LNP and MNP. Genes were selected in the enriched list when their expression fold change > 2 and p<0.05.

| MNP enriched genes | |

| gene symbol | gene description |

| 4930412O13Rik | RIKEN cDNA 4930412O13 gene |

| Alx3 | aristaless-like homeobox 3 |

| Ap4b1 | adaptor-related protein complex AP-4, beta 1 |

| Apbb3 | amyloid beta (A4) precursor protein-binding, family B, member 3 |

| Ccl21a | chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 21A (serine) |

| Cdk3-ps | cyclin-dependent kinase 3, pseudogene |

| Cnn2 | calponin 2 |

| Crtac1 | cartilage acidic protein 1 |

| Crym | 21rystalline, mu |

| D10Ertd610e | DNA segment, Chr 10, ERATO Doi 610, expressed |

| Dtx3 | deltex 3 homolog (Drosophila) |

| Foxf1a | forkhead box F1a |

| G530011O06Rik | RIKEN cDNA G530011O06 gene |

| Gata2 | GATA binding protein 2 |

| Ghrl | ghrelin |

| Haghl | hydroxyacylglutathione hydrolase-like |

| Htr3b | 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 3B |

| Isl2 | insulin related protein 2 (islet 2) |

| Lum | lumican |

| Mmaa | methylmalonic aciduria (cobalamin deficiency) type A |

| Mmp23 | matrix metallopeptidase 23 |

| Nup210l | nucleoporin 210-like |

| Pax9 | paired box gene 9 |

| Rgs5 | regulator of G-protein signaling 5 |

| Ripk3 | receptor-interacting serine-threonine kinase 3 |

| Rps6kb2 | ribosomal protein S6 kinase, polypeptide 2 |

| Sfpi1 | SFFV proviral integration 1 |

| Snai1 | snail homolog 1 (Drosophila) |

| Snord14c | small nucleolar RNA, C/D box 14C |

| Traf3ip2 | TRAF3 interacting protein 2 |

| Vsig2 | V-set and immunoglobulin domain containing 2 |

| LNP enriched genes | |

| gene symbol | gene description |

| 4933409K07Rik|Gm10590 | RIKEN cDNA 4933409K07 gene | predicted gene 10590 |

| Bicc1 | bicaudal C homolog 1 (Drosophila) |

| Gm10561 | predicted gene 10561 |

| Gsc | goosecoid homeobox |

| Hpgd | hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase 15 (NAD) |

| Iqcf1 | IQ motif containing F1 |

| Mirlet7d | microRNA let7d |

| Nfe2 | nuclear factor, erythroid derived 2 |

| Npw | neuropeptide W |

| S100a13 | S100 calcium binding protein A13 |

| Slc4a3 | solute carrier family 4 (anion exchanger), member 3 |

| Snhg1 | small nucleolar RNA host gene (non-protein coding) 1 |

| Snora69 | small nucleolar RNA, H/ACA box 69 |

| Snord33 | small nucleolar RNA, C/D box 33 |

| Tyrobp | TYRO protein tyrosine kinase binding protein |

| Vps13d | vacuolar protein sorting 13 D (yeast) |

| Wdr65 | WD repeat domain 65 |

Experimental Procedures

Animals

Sox10ERT2CreERT2 (SECE) transgenic mice

The ERT2CreERT2 fragment was digested directly from pCAG-ERT2CreERT2 (Addgene plasmid# 13777) (Matsuda and Cepko, 2007) and was inserted between the Sox10 MCS4 enhancer/c-Fos minimal promoter (Antonellis et al., 2008; Stine et al., 2009) and rabbit globin poly-adenylation sequence (pA). A 4.9 kb SpeI - AvrII fragment containing the promoter, ERT2CreERT2 and polyA sequences was used for pronuclear injection into C57BL6/C3H zygotes. Generated transgenic lines were backcrossed to several generations to 129S4 mice and crossed to R26R reporter mice (Soriano, 1999) to analyze Cre activity. The transgenic allele was genotyped by PCR using Cre primers (5′- GTTCGCAAGAACCTGATGGACA-3′ and 5′- CTAGAGCCTGTTTTGCACGTTC -3′) yielding a diagnostic 310 bp band.

PDGFRαfl/fl mice have been described previously (Tallquist and Soriano, 2003) and were maintained on a 129S4 background. R26R Cre reporter mice were maintained on a C57BL/6J background (Soriano, 1999).

Tamoxifen administration and X-gal staining

Tamoxifen (T-5648, Sigma) stock solution (20 mg/ml) was prepared by dissolving the powder in corn oil (C-8267, Sigma), and injected intraperitoneally (IP) to pregnant mice using 10-100 μg/g body weight doses between 11:00 AM and 1:00 PM. The embryos were collected at designated stages and subjected to X-gal staining (Friedrich and Soriano, 1991).

Immunostaining and BrdU labeling

Wild type embryos were dissected at E8.5 in ice cold PBS. Following fixation in 4% PFA/PBS overnight, they were dehydrated by increasing concentrations of sucrose in PBS, and embedded in O.C.T medium. Frontal cryosections were obtained at 5 μm and subjected to standard immunofluorescence staining protocol. Anti-Sox10 antibody (AF2864, R&D) was used at a 1:200 dilution. For BrdU labeling, pregnant mice were administered with BrdU solution (10 mg/ml in saline) at a dosage of 50 μg/g body weight. Staged embryos were collected 1 hour later, fixed in 4% PFA/PBS overnight, processed for dehydration and embedded in O.C.T medium. BrdU labeled cells were detected using an anti-BrdU primary antibody (1:50 dilution, G3G4, DSHB) and Cy3 conjugated affinipure donkey anti-mouse IgG (H+L) secondary antibody (1:300 dilution, 715-165-150, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories).

Acknowledgments

We thank Andy McCallion for the Sox10/MCS4 enhancer, Kevin Kelley in the Mt. Sinai Mouse Genetics Core for pronuclear microinjection and Tony Chen for excellent assistance with genotyping. The authors are grateful to Roland Friedel and Steve Potter for advice, and our laboratory colleagues for constructive comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH/NIDCR grant R01DE022363 to P.S. and NIH/NIDCR Pathway to Independence Award K99DE024617 to F.H.

Grant sponsor: NIH/NIDCR K99DE024617 to F.H. and R01DE022363 to P.S.

References

- Antonellis A, Huynh JL, Lee-Lin SQ, Vinton RM, Renaud G, Loftus SK, Elliot G, Wolfsberg TG, Green ED, McCallion AS, Pavan WJ. Identification of neural crest and glial enhancers at the mouse Sox10 locus through transgenesis in zebrafish. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000174. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoto K, Sandell LL, Butler Tjaden NE, Yuen KC, Watt KE, Black BL, Durnin M, Trainor PA. Mef2c-F10N enhancer driven beta-galactosidase (LacZ) and Cre recombinase mice facilitate analyses of gene function and lineage fate in neural crest cells. Dev Biol. 2015;402:3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breau MA, Pietri T, Stemmler MP, Thiery JP, Weston JA. A nonneural epithelial domain of embryonic cranial neural folds gives rise to ectomesenchyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7750–7755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711344105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronner ME, LeDouarin NM. Development and evolution of the neural crest: an overview. Dev Biol. 2012;366:2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.12.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunskill EW, Potter AS, Distasio A, Dexheimer P, Plassard A, Aronow BJ, Potter SS. A gene expression atlas of early craniofacial development. Dev Biol. 2014;391:133–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai Y, Jiang X, Ito Y, et al. Fate of the mammalian cranial neural crest during tooth and mandibular morphogenesis. Development. 2000;127:1671–1679. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.8.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielian PS, Muccino D, Rowitch DH, Michael SK, McMahon AP. Modification of gene activity in mouse embryos in utero by a tamoxifen-inducible form of Cre recombinase. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1323–1326. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00562-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon MJ, Marazita ML, Beaty TH, Murray JC. Cleft lip and palate: understanding genetic and environmental influences. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:167–178. doi: 10.1038/nrg2933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etchevers HC, Amiel J, Lyonnet S. Molecular bases of human neurocristopathies. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2006;589:213–234. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-46954-6_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantauzzo FA, Soriano P. PI3K-mediated PDGFRα signaling regulates survival and proliferation in skeletal development through p53-dependent intracellular pathways. Genes and Development. 2014;28:1005–1017. doi: 10.1101/gad.238709.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammill LS, Roffers-Agarwal J. Division of labor during trunk neural crest development. Dev Biol. 2010;344:555–565. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall BK. The neural crest and neural crest cells in vertebrate development and evolution. New York: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi S, Lewis P, Pevny L, McMahon AP. Efficient gene modulation in mouse epiblast using a Sox2Cre transgenic mouse strain. Mech Dev. 2002;119:S97–S101. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(03)00099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He F, Soriano P. A Critical Role for PDGFRalpha Signaling in Medial Nasal Process Development. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003851. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms JA, Cordero D, Tapadia MD. New insights into craniofacial morphogenesis. Development. 2005;132:851–861. doi: 10.1242/dev.01705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochheiser H, Aronow BJ, Artinger K, Beaty TH, Brinkley JF, Chai Y, Clouthier D, Cunningham ML, Dixon M, Donahue LR, Fraser SE, Hallgrimsson B, Iwata J, Klein O, Marazita ML, Murray JC, Murray S, de Villena FP, Postlethwait J, Potter S, Shapiro L, Spritz R, Visel A, Weinberg SM, Trainor PA. The FaceBase Consortium: a comprehensive program to facilitate craniofacial research. Dev Biol. 2011;355:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang R, Bush JO, Lidral AC. Development of the upper lip: morphogenetic and molecular mechanisms. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1152–1166. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Rowitch DH, Soriano P, McMahon AP, Sucov HM. Fate of the mammalian cardiac neural crest. Development. 2000;127:1607–1616. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.8.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlbrodt K, Herbarth B, Sock E, Hermans-Borgmeyer I, Wegner M. Sox10, a novel transcriptional modulator in glial cells. J Neurosci. 1998;18:237–250. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00237.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulesa PM, Bailey CM, Kasemeier-Kulesa JC, McLennan R. Cranial neural crest migration: New rules for an old road. Dev Biol. 2010;344:543–554. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulesa PM, Gammill LS. Neural crest migration: patterns, phases and signals. Dev Biol. 2010;344:566–568. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Douarin ML, Kalcheim C. The Neural Crest. London: Cambridge university press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Bedard O, Buchtova M, Fu K, Richman JM. A new origin for the maxillary jaw. Dev Biol. 2004;276:207–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis AE, Vasudevan HN, O'Neill AK, Soriano P, Bush JO. The widely used Wnt1-Cre transgene causes developmental phenotypes by ectopic activation of Wnt signaling. Dev Biol. 2013;379:229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda T, Cepko CL. Controlled expression of transgenes introduced by in vivo electroporation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1027–1032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610155104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka T, Ahlberg PE, Kessaris N, Iannarelli P, Dennehy U, Richardson WD, McMahon AP, Koentges G. Neural crest origins of the neck and shoulder. Nature. 2005;436:347–355. doi: 10.1038/nature03837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie IA, Ohayon D, Li H, de Faria JP, Emery B, Tohyama K, Richardson WD. Motor skill learning requires active central myelination. Science. 2014;346:318–322. doi: 10.1126/science.1254960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo-Muller V, Muneoka K. In utero and exo utero surgery on rodent embryos. Methods Enzymol. 2010;476:205–226. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)76012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noden DM. The control of avian cephalic neural crest cytodifferentiation: II. Neural tissues. Dev Biol. 1978;67:313–329. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(78)90202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noden DM. Interactions and fates of avian craniofacial mesenchyme. Development. 1988;103:121–140. doi: 10.1242/dev.103.Supplement.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osumi-Yamashita N, Ninomiya Y, Eto K, Doi H. The contribution of both forebrain and midbrain crest cells to the mesenchyme in the frontonasal mass of mouse embryos. Dev Biol. 1994;164:409–419. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietri T, Eder O, Blanche M, Thiery JP, Dufour S. The human tissue plasminogen activator-Cre mouse: a new tool for targeting specifically neural crest cells and their derivatives in vivo. Dev Biol. 2003;259:176–187. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00175-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pusch C, Hustert E, Pfeifer D, Sudbeck P, Kist R, Roe B, Wang Z, Balling R, Blin N, Scherer G. The SOX10/Sox10 gene from human and mouse: sequence, expression, and transactivation by the encoded HMG domain transcription factor. Hum Genet. 1998;103:115–123. doi: 10.1007/s004390050793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serbedzija GN, Bronner-Fraser M, Fraser SE. Vital dye analysis of cranial neural crest cell migration in the mouse embryo. Development. 1992;116:297–307. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.2.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon C, Lickert H, Gotz M, Dimou L. Sox10-iCreERT2 : a mouse line to inducibly trace the neural crest and oligodendrocyte lineage. Genesis. 2012;50:506–515. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. The PDGF alpha receptor is required for neural crest cell development and for normal patterning of the somites. Development. 1997;124:2691–2700. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.14.2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet. 1999;21:70–71. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southard-Smith EM, Kos L, Pavan WJ. Sox10 mutation disrupts neural crest development in Dom Hirschsprung mouse model. Nat Genet. 1998;18:60–64. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stine ZE, Huynh JL, Loftus SK, Gorkin DU, Salmasi AH, Novak T, Purves T, Miller RA, Antonellis A, Gearhart JP, Pavan WJ, McCallion AS. Oligodendroglial and pan-neural crest expression of Cre recombinase directed by Sox10 enhancer. Genesis. 2009;47:765–770. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallquist MD, Soriano P. Cell autonomous requirement for PDGFR in populations of cranial and cardiac neural crest cells. Development. 2003;130:507–518. doi: 10.1242/dev.00241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theveneau E, Mayor R. Neural crest delamination and migration: from epithelium-to-mesenchyme transition to collective cell migration. Dev Biol. 2012;366:34–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]