Abstract

Very limited information is available concerning the epidemiology of T. gondii infection in pregnant women in eastern China. Therefore, a case-control study was conducted to estimate the seroprevalence of toxoplasmosis in this population group and to identify risk factors and possible routes of contamination. Serum samples were collected from 965 pregnant women and 965 age-matched nonpregnant control subjects in Qingdao and Weihai between October 2011 and July 2013. These were screened with enzyme linked immunoassays for the presence of anti-Toxoplasma IgG and anti-Toxoplasma IgM antibodies. 147 (15.2%) pregnant women and 167 (17.3%) control subjects were positive for anti-T. gondii IgG antibodies, while 28 (2.9%) pregnant women and 37 (3.8%) controls were positive for anti-T. gondii IgM antibodies (P = 0.256). There was no significant difference between pregnant women and nonpregnant controls with regard to the seroprevalence of either anti-T. gondii IgG or IgM antibodies. Multivariate analysis showed that T. gondii infection was associated with location, cats in home, contact with cats and dogs, and exposure to soil. The results indicated that the seroprevalence of T. gondii infection in pregnant women is high compared to most other regions of China and other East Asian countries with similar climatic conditions.

1. Introduction

Toxoplasma gondii is an obligate intracellular protozoan parasite distributed globally in humans and other warm-blooded animals [1, 2]. It is estimated that approximately one-third of the world's human population has been exposed to T. gondii [3]. Humans become infected by ingesting food or water contaminated with oocysts shed by cats; by eating undercooked or raw meat containing tissue cysts; or congenitally by transplacental transmission of tachyzoites [1, 4]. Most infections are asymptomatic but in some individuals, especially if immunocompromised, the parasite can become widely disseminated causing severe clinical signs including encephalitis [5]. Primary infection during pregnancy can result in severe damage to the fetus manifested as mental retardation, seizures, blindness, or even death [6]. The rate of congenital transmission and the degree of severity of toxoplasmosis in fetuses vary depending largely on the stage of gestation at the time of infection, the risk of transmission being lower in the first trimester and higher during the last trimester [7]. Therefore, early diagnosis of T. gondii infection during pregnancy is very important for prevention of congenital toxoplasmosis.

Epidemiological studies recording prevalence of T. gondii infection in pregnant women around the world indicate considerable variation between countries, ranging, for example, from 9% to 67% in European countries [7–12] and reaching as high as 92.5% in Ghana [13]. Similarly, high prevalence of T. gondii infection has also been found in some American countries [14–17]. In contrast, prevalence was relatively low in East Asian countries, especially in Korea [18] and Japan [19]. There is little information about the epidemiology of T. gondii infection in pregnant women in China [20, 21] and earlier studies have been published in Chinese. This case-control study was performed to estimate the seroprevalence of T. gondii infection in pregnant women in two regions of eastern China and to identify associated risk factors and possible routes of contamination.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

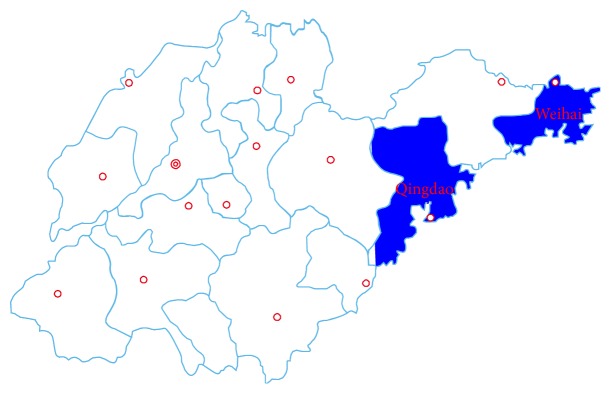

Through a case-control study, we studied the seroprevalence of T. gondii infection in pregnant women and control subjects in Qingdao and Weihai, eastern China (Figure 1), from October 2011 to July 2013 and used a questionnaire to identify risk factors and possible routes of transmission.

Figure 1.

Geographic distribution of study regions in Shandong province, eastern China.

2.2. Sample Collection and Transportation

965 pregnant women attending hospital for antenatal care or medication were recruited for this study. Their age ranged from 17 to 43. A similar number of age-matched nonpregnant women were selected as control subjects. About 5 mL of venous blood was collected aseptically from each of the study participants. Serum separated from whole blood by centrifugation at 2000 ×g for 5 min. was labeled and kept at −20°C until used.

2.3. Questionnaire Survey

A structured questionnaire was used to assess risk factors, which included study location, age, residential area, pregnancy status, stage of pregnancy, presence of cats and dogs in home, contact with cats and dogs, consumption of raw/undercooked meat, consumption of raw vegetables and fruits, source of drinking water, and exposure to soil. These variables had been selected based on the literature.

2.4. Serological Assay

Sera were tested for anti-T. gondii IgG and IgM antibodies using ELISA test kits (Demeditec Diagnostics GmbH, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions. Optical densities were measured by photometer at a wavelength of 450 nm. Values higher than the cut-off (10 IU/mL) were considered positive. Values ±20% of the cut-off were considered to be equivocal and retested.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Results were analyzed with the SPSS 19.0 software package. For comparison of frequencies among groups, the Mantel-Haenszel Chi square test and, when appropriate, the Fisher exact test were used. Bivariate and multivariate analyses were used to assess the association between characteristics of subjects and T. gondii infection. Variables were included in the multivariate analysis if they had a P value ≤ 0.25 in the bivariate analysis. Adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated by multivariable analysis using multiple, unconditional, logistic regression. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.6. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved before its commencement by the ethical committee of the Affiliated Hospital of the Medical College, Qingdao University, Wendeng Municipal Hospital, and Wendeng Stomatology Hospital. The purpose of and procedures involved in the study were explained and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Sera were collected with the consent of the volunteers.

3. Results

Anti-T. gondii IgG antibodies were found in 147 (15.2%) of 965 pregnant women and in 167 (17.3%) of 965 control subjects (P = 0.217). Twenty-eight (2.9%) pregnant women and 37 (3.8%) controls were positive for anti-T. gondii IgM antibodies (P = 0.256). Among pregnant women, 122 (12.6%) were positive for IgG antibodies only compared to 137 (14.2%) of controls. Three (0.3%) pregnant women and seven (0.7%) controls were positive for IgM antibodies only, while 2.6% pregnant women and 3.1% controls were positive for both IgG and IgM antibodies. Detailed information is summarized in Table 1. Univariate analysis of sociodemographic and risk factors for pregnant women and controls identified some factors with a P value ≤ 0.25 that may be related to infection (Table 2). Four of these were found to be significantly associated with T. gondii infection in multivariable analysis (Table 3): residence area, cats in home, contact with cats and dogs, and exposure to soil.

Table 1.

Combined IgG and IgM anti-T. gondii antibodies seroprevalence in pregnant women and controls.

| Seroreaction | Pregnant women | Controls | Total | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 965) | (N = 965) | (N = 1930) | |||||

| Positive | % | Positive | % | Positive | % | ||

| Positive for IgG only | 122 | 12.6 | 137 | 14.2 | 259 | 13.4 | 0.32 |

| Positive for IgM only | 3 | 0.3 | 7 | 0.7 | 10 | 0.5 | 0.21 |

| Positive for IgG and IgM | 25 | 2.6 | 30 | 3.1 | 55 | 2.8 | 0.49 |

| Negative for IgG and IgM | 815 | 84.5 | 791 | 82.0 | 1606 | 83.2 | 0.14 |

| Positive for either IgG or IgM | 150 | 15.5 | 174 | 18.0 | 324 | 16.8 | 0.14 |

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and risk factors associated with Toxoplasma seropositivity in pregnant women and controls by univariate analysis.

| Characteristic | Pregnant women (N = 965) | Controls (N = 965) | Total (N = 1930) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number tested | Number positive | % | P value | Number tested | Number positive | % | P value | Number tested | Number positive | % | P value | |

| Age group (years) | ||||||||||||

| 25 or less | 339 | 47 | 13.9 | 0.17 | 252 | 44 | 17.5 | 0.49 | 591 | 91 | 15.4 | 0.03 |

| 26–35 | 467 | 68 | 13.7 | 551 | 90 | 16.3 | 1018 | 158 | 15.5 | |||

| >35 | 159 | 32 | 20.1 | 162 | 33 | 20.4 | 321 | 65 | 20.2 | |||

| Location | ||||||||||||

| Qingdao | 445 | 69 | 15.5 | 0.83 | 415 | 77 | 18.6 | 0.37 | 860 | 146 | 17.0 | 0.45 |

| Weihai | 520 | 78 | 15.0 | 550 | 90 | 16.4 | 1070 | 168 | 15.7 | |||

| Residence area | ||||||||||||

| Urban | 534 | 70 | 13.1 | 0.04 | 386 | 60 | 15.5 | 0.24 | 920 | 130 | 14.1 | 0.02 |

| Rural | 431 | 77 | 17.9 | 579 | 107 | 18.5 | 1010 | 184 | 18.2 | |||

| Cat at home | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 14 | 4 | 28.6 | 0.16 | 108 | 33 | 30.6 | <0.001 | 122 | 37 | 30.3 | <0.001 |

| No | 951 | 143 | 15.0 | 857 | 134 | 15.6 | 1808 | 277 | 15.3 | |||

| Dog at home | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 182 | 22 | 12.1 | 0.19 | 280 | 35 | 12.5 | 0.01 | 462 | 57 | 12.3 | 0.009 |

| No | 783 | 125 | 16.0 | 685 | 132 | 19.3 | 1468 | 257 | 17.5 | |||

| Contact with cat and dog | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 203 | 74 | 36.5 | <0.001 | 429 | 113 | 26.3 | <0.001 | 632 | 187 | 29.6 | <0.001 |

| No | 762 | 73 | 9.58 | 536 | 54 | 10.1 | 1298 | 127 | 9.78 | |||

| Consumption of raw vegetables and fruits | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 545 | 92 | 16.9 | 0.11 | 688 | 127 | 18.5 | 0.14 | 1233 | 219 | 17.8 | 0.02 |

| No | 420 | 55 | 13.1 | 277 | 40 | 14.4 | 697 | 95 | 13.6 | |||

| Consumption of raw/undercooked meat | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 692 | 108 | 15.6 | 0.61 | 625 | 118 | 18.9 | 0.08 | 1317 | 226 | 17.2 | 0.12 |

| No | 273 | 39 | 14.3 | 340 | 49 | 14.4 | 613 | 88 | 14.4 | |||

| Exposure to soil | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 572 | 98 | 17.1 | 0.048 | 731 | 137 | 18.7 | 0.037 | 1303 | 235 | 18.0 | 0.002 |

| No | 393 | 49 | 12.5 | 234 | 30 | 12.8 | 627 | 79 | 12.6 | |||

| Source of drinking water | ||||||||||||

| Tap | 715 | 110 | 15.4 | 0.83 | 642 | 112 | 17.4 | 0.871 | 1357 | 222 | 16.4 | 0.87 |

| Well + river | 250 | 37 | 14.8 | 323 | 55 | 17.0 | 573 | 92 | 16.1 | |||

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of selected characteristics of the participants and their association with T. gondii infection.

| Characteristica | Adjusted odds ratiob | 95% confidence interval | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Residence area | 1.55 | 1.15–2.18 | 0.010 |

| Cats in home | 3.45 | 2.40–4.91 | <0.001 |

| Dogs in home | 1.08 | 0.87–1.49 | 0.48 |

| Contact with cats and dogs | 3.07 | 2.33–4.12 | <0.001 |

| Consumption of raw vegetables and fruits | 1.03 | 0.81–1.31 | 0.64 |

| Consumption of raw/undercooked meat | 1.13 | 0.83–1.53 | 0.44 |

| Exposure to soil | 1.66 | 1.18–2.34 | 0.004 |

aThe variables included were those with a P < 0.25 obtained in the bivariate analysis.

bAdjusted by age and the rest of characteristics included in this table.

4. Discussion

In this study, we found the seroprevalence of T. gondii infection in pregnant women and control subjects to be 15.2% and 17.3%, respectively. These figures are considerably higher than the 7.9% estimated for the general population by a national survey of parasitic disease conducted by the Ministry of Health of China from 2001 to 2004 [22]. However, the prevalence of pregnant women in this study was lower than that observed previously in Liaoning (21.5%) [23], Hubei (22.8%) [24], and Taiwan (31.06%) [25] but much higher than that in Zhejiang (0.17%) [26]. These differences could be related to environmental factors favoring the transmission and infectivity of T. gondii oocysts as Qingdao and Weihai both have a marine climate with moist air and abundant rainfall transmission [27], together with an appropriate temperature during most of the year (being neither too hot in summer nor too cold in winter and with an annual average temperature of 12.7°C). Other factors such as different study populations, numbers of cats, diagnostic methods, and living styles may also contribute to these differences.

It is known that felines are the only definitive hosts responsible for contaminating the domestic and wider environment with oocysts. These can remain infective for a long time, especially in water or soil. Contact with domestic cats is often mentioned as a risk factor but there are also contradictory reports. In our study there was a significant association between T. gondii infection and the presence of domestic cats in home, indicating that it was a risk factor. This result corroborates with studies reported from France [28] and China [20]. In contrast, some other studies reported an absence of association between Toxoplasma infection and the presence of domestic cats in the household [28–30]. Actually, occasional contact with or ownership of cats may not necessarily be a risk factor, whereas frequent exposure to feline feces or neglect of preventive measures (i.e., not washing hands or wearing gloves) may enhance the risk of infection to an appreciable level. In China, with the continuous development of society and improvement of human well-being, more and more people are starting to keep pets, including cats and dogs. This, together with inadequate inspection and quarantine measures, could enhance the potential risk to pet owners of zoonotic hazards such as Toxoplasma. Moreover, the prevalence of this parasite among domestic cat populations in different countries may depend on the type of cat (e.g., stray versus pet cats) since stray cats were reported to be more exposed to the parasite than pet cats [31]. In locations surveyed in the present study, large numbers of stray cats roam streets and public places in both urban and rural areas. Not only is it stray cats that pollute the environment indiscriminately but also many owners allow indoor cats to defecate outside home. Consequently, there is a high chance of T. gondii oocysts contaminating the environment and being transmitted to humans and it was expected that the prevalence would be higher.

Our data and those of other studies [20, 28, 32] have shown that living in rural or suburban regions with exposure to soil is another risk factor for pregnant women. In some environments, oocysts can remain viable for years [33]. Therefore, all soil, sand, and untreated water should be considered as a potential source of infection for humans; this might explain the higher frequency of infection in pregnant women who frequently come into contact with soil without using gloves compared to women not exposed in this way. In addition, residence is not an isolated factor; in China, rural or suburban residence is generally associated with poorer sanitary facilities, more frequent contact with soil or animals, and drinking unboiled water. These factors enhance the risk of T. gondii infection in pregnant women, especially in those who live in rural or suburban regions.

Our results demonstrate that T. gondii infection was not associated with consumption of raw vegetables and fruits, consumption of raw/undercooked meat, or specific source of drinking water. Such factors have been found to be significant in previously reported studies [20, 29, 31, 34]. This strongly suggests that, despite our findings, T. gondii infection in pigs, cattle, sheep, and chicken in China may nevertheless be contributing risk because local residents frequently consume roasted pork, raw beef, and instant-boiled mutton in the study area. Further large-scale studies should be conducted to estimate the association between risk factors and T. gondii infection in China.

It is known that avoiding infection during pregnancy is the most effective method of preventing congenital toxoplasmosis. There are many health centers and obstetric departments, both in China and in the rest of the world, that do not take any measures to prevent or inform patients of the risk of toxoplasmosis. Therefore, the present results serve to alert public health administrative departments of the need to undertake large scale studies to define economic and health impacts of this zoonosis and to formulate guidelines and policies aimed at mitigating its potentially destructive outcomes. In addition, a health promotion strategy in this field should be based on making women of reproductive age aware of infection risk factors, thereby leading to a change in health behavior. Finally, there is also a need to control stray cat populations to reduce the risk of zoonotic transmission of the parasite.

Acknowledgments

Project support was provided in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 31230073), the Science Fund for Creative Research Groups of Gansu Province (Grant no. 1210RJIA006), and The Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program (ASTIP) (Grant no. CAAS-ASTIP-2014-LVRI-03). The authors thank Professor Dennis Jacobs for copy-editing the paper.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Dubey J. P. Toxoplasmosis of Animals and Humans. 2nd. Boca Raton, Fla, USA: CRC Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montoya J. G., Liesenfeld O. Toxoplasmosis. The Lancet. 2004;363(9425):1965–1976. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(04)16412-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tenter A. M., Heckeroth A. R., Weiss L. M. Toxoplasma gondii: from animals to humans. International Journal for Parasitology. 2000;30(12-13):1217–1258. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(00)00124-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montoya J. G., Rosso F. Diagnosis and management of toxoplasmosis. Clinics in Perinatology. 2005;32(3):705–726. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atreya A. R., Arora S., Gadiraju V. T., Martagon-Villamil J., Skiest D. J. Toxoplasma encephalitis in an HIV-infected patient on highly active antiretroviral therapy despite sustained immune response. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2014;25(5):383–386. doi: 10.1177/0956462413506891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torgerson P. R., Mastroiacovo P. The global burden of congenital toxoplasmosis: a systematic review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2013;91(7):501–508. doi: 10.2471/blt.12.111732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopes A. P., Dubey J. P., Moutinho O., et al. Seroepidemiology of Toxoplasma gondii infection in women from the North of Portugal in their childbearing years. Epidemiology and Infection. 2012;140(5):872–877. doi: 10.1017/s0950268811001658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ertug S., Okyay P., Turkmen M., Yuksel H. Seroprevalence and risk factors for toxoplasma infection among pregnant women in Aydin province, Turkey. BMC Public Health. 2005;15(5):p. 66. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maggi P., Volpe A., Carito V., et al. Surveillance of toxoplasmosis in pregnant women in Albania. The New Microbiologica. 2009;32(1):89–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nash J. Q., Chissel S., Jones J., Warburton F., Verlander N. Q. Risk factors for toxoplasmosis in pregnant women in Kent, United Kingdom. Epidemiology and Infection. 2005;133(3):475–483. doi: 10.1017/S0950268804003620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramos J. M., Milla A., Rodríguez J. C., Padilla S., Masiá M., Gutiérrez F. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii infection among immigrant and native pregnant women in Eastern Spain. Parasitology Research. 2011;109(5):1447–1452. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2393-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uysal A., Cüce M., Tañer C. E., et al. Prevalence of congenital toxoplasmosis among a series of Turkish women. Revista Médica de Chile. 2013;141(4):471–476. doi: 10.4067/s0034-98872013000400008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ayi I., Edu S., Apea-kubi K., Boamah D., Bosompem K., Edoh D. Sero-epidemiology of toxoplasmosis amongst pregnant women in the greater Accra region of Ghana. Ghana Medical Journal. 2010;43(3):107–114. doi: 10.4314/gmj.v43i3.55325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bittencourt L. H. F., Lopes-Mori F. M. R., Mitsuka-Breganó R., et al. Seroepidemiology of toxoplasmosis in pregnant women since the implementation of the Surveillance Program of Toxoplasmosis Acquired in Pregnancy and Congenital in the western region of Paraná, Brazil. Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia. 2012;34(2):63–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monsalve-Castillo F. M., Costa-León L. A., Castellano M. E., Suárez A., Atencio R. J. Prevalence of infectious agents in indigenous women of childbearing age in venezuela. Biomedica. 2012;32(4):519–526. doi: 10.7705/biomedica.v32i4.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramsewak S., Gooding R., Ganta K., Seepersadsingh N., Adesiyun A. A. Seroprevalence and risk factors of Toxoplasma gondii infection among pregnant women in Trinidad and Tobago. Revista Panamericana de Salud Publica. 2008;23(3):164–170. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892008000300003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rebouças E. C., Dos Santos E. L., Carmo M. L. S. D., Cavalcante Z., Favali C. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma infection among pregnant women in Bahia, Brazil. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2011;105(11):670–671. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song K.-J., Shin J.-C., Shin H.-J., Nam H.-W. Seroprevalence of toxoplasmosis in Korean pregnant women. The Korean Journal of Parasitology. 2005;43(2):69–71. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2005.43.2.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakikawa M., Noda S., Hanaoka M., et al. Anti-Toxoplasma antibody prevalence, primary infection rate, and risk factors in a study of toxoplasmosis in 4,466 pregnant women in Japan. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology. 2012;19(3):365–367. doi: 10.1128/cvi.05486-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Q., Wei F., Gao S., et al. Toxoplasma gondii infection in pregnant women in China. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2009;103(2):162–166. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xin K.-S., Pan M., Liu H., Dong R.-R. Investigation of Toxoplasma gondii infection in pregnant women in Qingdao area. Chinese Journal of Schistosomiasis Control. 2014;26(3):320–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou P., Chen Z., Li H.-L., et al. Toxoplasma gondii infection in humans in China. Parasites & Vectors. 2011;4(1, article 165) doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang D. H., Wang F. Z., Fan H., et al. A seroepidemiologic survey on Toxoplasma gondii infection of pregnant women. Chinese Primary Health Care. 2004;8(4):29–30. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu J., Jun Z. TORCH infection among women at early pregnancy in Hanyang district,Wuhan. Chinese Journal of Birth Health & Heredity. 2009;17(6):70–71. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin Y.-L., Liao Y.-S., Liao L.-R., Chen F.-N., Kuo H.-M., He S. Seroprevalence and sources of Toxoplasma infection among indigenous and immigrant pregnant women in Taiwan. Parasitology Research. 2008;103(1):67–74. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-0928-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y. C., Zhang L. H., Yuan K. Investigation of TORCH infection in pregnant women and newborns in Insular district in Zhejiang Province. Chinese Journal of Birth Health & Heredity. 2001;18(2):87–88. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alvarado-Esquivel C., Sifuentes-Álvarez A., Narro-Duarte S. G., et al. Seroepidemiology of Toxoplasma gondii infection in pregnant women in a public hospital in northern Mexico. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2006;6, article 113 doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baril L., Ancelle T., Goulet V., Thulliez P., Tirard-Fleury V., Carme B. Risk factors for Toxoplasma infection in pregnancy: a case-control study in France. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1999;31(3):305–309. doi: 10.1080/00365549950163626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gebremedhin E. Z., Abebe A. H., Tessema T. S., et al. Seroepidemiology of Toxoplasma gondii infection in women of child-bearing age in central Ethiopia. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2013;26(13):p. 101. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mwambe B., Mshana S. E., Kidenya B. R., et al. Sero-prevalence and factors associated with Toxoplasma gondii infection among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Mwanza, Tanzania. Parasites & Vectors. 2013;6(6, article 222) doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu S.-M., Huang S.-Y., Fu B.-Q., et al. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii infection in pet dogs in Lanzhou, Northwest China. Parasites & Vectors. 2011;4, article 64 doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fromont E. G., Riche B., Rabilloud M. Toxoplasma seroprevalence in a rural population in France: detection of a household effect. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2009;9, article 76 doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Torrey E. F., Yolken R. H. Toxoplasma oocysts as a public health problem. Trends in Parasitology. 2013;29(8):380–384. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andiappan H., Nissapatorn V., Sawangjaroen N., et al. Toxoplasma infection in pregnant women: a current status in Songklanagarind hospital, southern Thailand. Parasites & Vectors. 2014;7(1, article no. 239) doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]