Abstract

Objective

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is associated with increased mortality after surgical or transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) for aortic stenosis (AS) and when the pulmonary artery pressure is particularly elevated there may be questions about the clinical benefit of TAVR. We aimed to identify clinical and hemodynamic factors associated with increased mortality after TAVR among those with moderate/severe PH.

Methods

Among patients with symptomatic AS at high or prohibitive surgical risk receiving TAVR in the Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves (PARTNER) I randomized trial or registry, 2180 patients with an invasive measurement of mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) recorded were included and moderate/severe PH was defined as a mPAP ≥35mmHg.

Results

Increasing severity of PH was associated with progressively worse 1-year all-cause mortality: none (n=785, 18.6%), mild (n=838, 22.7%), and moderate/severe (n=557, 25.0%) (p=0.01). The increased hazard of mortality associated with moderate/severe PH was observed in females but not males (interaction p=0.03). In adjusted analyses, females with moderate/severe PH had an increased hazard of death at 1 year compared to females without PH (adjusted HR 2.14, 95% CI 1.44–3.18), whereas those with mild PH did not. Among males, there was no increased hazard of death associated with any severity of PH. In a multivariable Cox model of patients with moderate/severe PH, oxygen dependent lung disease, inability to perform a 6 minute walk, impaired renal function, and lower aortic valve mean gradient were independently associated with increased 1-year mortality (p<0.05 for all), whereas several hemodynamic indices were not. A risk score including these factors was able to identify patients with a 15% versus 59% 1-year mortality.

Conclusion

The relationship between moderate/severe PH and increased mortality after TAVR is altered by sex and clinical factors appear to be more influential in stratifying risk than hemodynamic indices. These findings may have implications for the evaluation of and treatment decisions for patients referred for TAVR with significant PH.

Keywords: aortic valve stenosis, pulmonary hypertension, transcatheter aortic valve replacement, outcomes

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is an emerging risk factor for increased mortality after surgical and transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR).[1–4] Patients with very elevated pulmonary pressures may be turned down for valve replacement due to concerns about high peri-operative morbidity and mortality or questions about whether valve replacement will yield clinical benefit.[5] There is uncertainty regarding how to further risk stratify this sub-group of patients and what factors are associated with an acceptable versus poor clinical outcome. In this regard, pulmonary vascular resistance or its reversibility in response to vasodilator challenge is sometimes considered to suggest whether the pulmonary hypertension is reversible and to indicate the likelihood of clinical improvement.[6 7] Whether this approach has validity is unknown.[8] Accordingly, we evaluated the effect of clinical and hemodynamic factors on mortality among patients with moderate or severe PH undergoing TAVR in the PARTNER (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves) I randomized trial and continued access registry. We hypothesized that a combination of clinical and hemodynamic factors would refine risk stratification of patients with significant PH, which could have important implications for treatment decisions of this higher risk population.

METHODS

Study population

The design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and primary results of the high-risk (Cohort A) and prohibitive risk (Cohort B) cohorts of the PARTNER I randomized clinical trial have been reported.[9 10] The inclusion and exclusion criteria for high-risk and prohibitive risk patients enrolled in the continued access registry were the same as those enrolled in the randomized trial.[9 10] Patients were symptomatic (NYHA functional class ≥2) and had severe AS with an aortic valve area (AVA) <0.8 cm2 (or indexed AVA <0.5 cm2/m2) and either resting or inducible mean gradient >40 mmHg or peak jet velocity >4 m/s. High surgical risk was defined by a predicted risk of death of 15% or higher by 30 days after conventional surgery.[10] Patients at prohibitive risk were not considered to be suitable candidates for surgery due to a predicted probability of death or a serious irreversible condition of 50% or higher by 30 days after conventional surgery.[9] Based on an assessment of vascular anatomy, patients were deemed suitable for either a transfemoral or transapical approach and, if enrolled in the trial, randomized to transcatheter therapy with the Edwards-SAPIEN heart valve system (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, California) or surgical aortic valve replacement (Cohort A) or transcatheter therapy or medical therapy (Cohort B). For this analysis, we included only patients who received treatment with TAVR (the “as treated” population) who also had an invasive measurement of pulmonary artery pressure recorded at the time of the TAVR procedure prior to balloon aortic valvuloplasty. Clinical characteristics were reported by the enrolling sites. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each enrolling site and all patients provided written informed consent.

Hemodynamics and Echocardiography

A pulmonary artery catheter was routinely used during the TAVR cases to obtain invasive hemodynamic measurements before balloon aortic valvuloplasty and after transcatheter valve placement. The measurements obtained prior to balloon aortic valvuloplasty were utilized for this analysis. PH was defined as: any PH (mean pulmonary artery pressure [mPAP] ≥25 mmHg), mild PH (mPAP 25 mmHg to <35 mmHg), moderate PH (mPAP 35 mmHg to <45 mmHg), and severe PH (mPAP ≥45 mmHg). Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) = (mPAP – mean pulmonary capillary wedge pressure) / cardiac output. Pulmonary artery compliance (PAC) = stroke volume index (determined by echocardiography) / pulmonary artery pulse pressure. An independent core laboratory analyzed all echocardiograms as previously described; the baseline echocardiogram obtained within 45 days prior to TAVR was used in this analysis.[11 12] Stroke volume was calculated as the left ventricular outflow tract area multiplied by the pulsed wave Doppler LV outflow tract velocity-time integral and indexed to BSA.

Clinical endpoints

Clinical events including all-cause death, cardiac death, repeat hospitalizations, stroke, renal failure, major bleeding, and vascular complications were adjudicated by a clinical events committee and defined previously.[9 10] Disease-specific health status was assessed with the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ); the overall summary score was the primary health status outcome for the PARTNER trial.[13–15]

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were summarized as mean±SD or medians and quartiles, as appropriate, and compared using ANOVA for means or Kruskal–Wallis test for medians. Categorical variables were described as n (%) and compared using the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. Survival curves for time-to-event variables, based on all available follow-up data, were performed with the use of Kaplan-Meier estimates and were compared between groups with the use of the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards models were used to calculate hazard ratios and to test for interactions. The proportional hazards assumption was checked and verified for each of the Cox models by creating interactions of the predictors and survival time and none were found to be significant. Variables included in the multivariable Cox models were forced (age, sex) or had a univariable association (p<0.10) with 1-year all-cause death. To improve risk stratification among patients with moderate or severe PH, we evaluated the effect of having a progressive number of the factors that were independently associated with mortality in this population. Based on the β-estimates for each of the independent predictors of mortality in the multivariable model, the variables were weighted and a risk score was developed with scale 0–8. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS software, version 9.2. A p-value of <0.05 indicates evidence of a statistically significant effect.

RESULTS

Patient population

Among 2180 patients with symptomatic AS at high or prohibitive surgical risk receiving TAVR in the PARTNER I trial or continued access registry, 436 (20%) were enrolled in the trial (Cohort A, n=286; Cohort B, n=150) and 1744 (80%) were in the continued access registry (Cohort A, n=1508, Cohort B, n=236). A transfemoral approach was utilized in 59% of patients and the remainder were treated via a transapical approach. Clinical, echocardiographic, and hemodynamic characteristics are shown in Table 1. Higher pulmonary artery pressure was associated with higher body mass index, lower EF and indexed AVA, and a greater prevalence of diabetes, NYHA functional class 4 symptoms, major arrhythmia, obstructive lung disease, and moderate to severe mitral and aortic regurgitation (Table 1). In contrast, there was no association between pulmonary artery pressure and sex or the prevalence of systemic hypertension, smoking, or renal impairment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics according to pulmonary hypertension severity

| No PH (n=785) |

Mild PH (n=838) |

Mod/Sev PH (n=557) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical | ||||

| Age (years) | 85 ± 7 | 84 ± 7 | 83 ± 8 | <0.001 |

| Female | 376 (48%) | 394 (47%) | 260 (47%) | 0.89 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.8 ± 5.1 | 27.3 ± 6.6 | 27.7 ± 7.1 | <0.001 |

| STS Score | 11.1 ± 4.2 | 11.4 ± 3.8 | 11.7 ± 3.8 | 0.05 |

| Smoking (current or prior) | 359 (46%) | 416 (50%) | 277 (50%) | 0.20 |

| Hypertension | 726 (93%) | 768 (92%) | 500 (90%) | 0.24 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 247 (32%) | 335 (40%) | 235 (42%) | <0.001 |

| NYHA class 4 | 324 (41%) | 398 (48%) | 267 (48%) | 0.02 |

| Coronary disease | 612 (78%) | 635 (76%) | 446 (80%) | 0.19 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 168 (22%) | 229 (28%) | 153 (28%) | 0.009 |

| Prior coronary artery bypass surgery | 319 (41%) | 342 (41%) | 271 (49%) | 0.005 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 202 (27%) | 234 (28%) | 149 (27%) | 0.69 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 341 (44%) | 375 (45%) | 225 (41%) | 0.21 |

| Major arrhythmia | 341 (44%) | 433 (52%) | 329 (59%) | <0.001 |

| Permanent pacemaker | 144 (18%) | 177 (21%) | 127 (23%) | 0.12 |

| Renal disease (creatinine ≥2) | 125 (16%) | 140 (17%) | 90 (16%) | 0.89 |

| Liver disease | 12 (1.5%) | 22 (2.6%) | 23 (4.2%) | 0.01 |

| Chronic obstructive lung disease | 329 (42%) | 410 (49%) | 268 (48%) | 0.01 |

| Oxygen dependent | 69 (9%) | 105 (13%) | 250 (14%) | 0.01 |

| Echocardiography | ||||

| LV ejection fraction (%) | 58 (50, 63) | 55 (45, 60) | 55 (37, 60) | <0.001 |

| LVMi (g/m2) | 129 (108, 156) | 133 (111, 162) | 139 (118, 168) | <0.001 |

| Stroke volume index (ml/m2) | 37 (30, 44) | 34 (28, 42) | 32 (26, 40) | <0.001 |

| LV end-diastolic dimension (cm) | 4.3 (3.8, 4.8) | 4.5 (4.0, 5.0) | 4.7 (4.1, 5.2) | <0.001 |

| LV end-systolic dimension (cm) | 3.0 (2.5, 3.6) | 3.2 (2.6, 3.9) | 3.4 (2.7, 4.3) | <0.001 |

| AVA index (cm2/m2) | 0.37 (0.30, 0.44) | 0.36 (0.29, 0.42) | 0.33 (0.27, 0.40) | <0.001 |

| AV mean gradient (mmHg) | 42 (34, 52) | 42 (34, 51) | 42 (33, 54) | 0.84 |

| AV peak gradient (mmHg) | 69 (57, 83) | 68 (56, 83) | 68 (55, 87) | 0.76 |

| Moderate and severe total AR (%) | 72 (9%) | 91 (11%) | 78 (15%) | 0.01 |

| Moderate and severe MR (%) | 118 (15%) | 203 (25%) | 155 (29%) | <0.001 |

| Hemodynamics | ||||

| RA pressure (mean) (mmHg) | 8 (6, 11) | 12 (9, 15) | 16 (12, 20) | <0.001 |

| PA systolic pressure (mmHg) | 30 (26, 34) | 42 (38, 46) | 60 (53, 68) | <0.001 |

| PA diastolic pressure (mmHg) | 14 (11, 16) | 21 (18, 23) | 29 (25, 33) | <0.001 |

| PA pressure (mean) (mmHg) | 20 (17, 22) | 29 (27, 32) | 41 (37, 46) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (mmHg) | 13 (10, 17) | 20 (17, 24) | 26 (21, 31) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance (Wood units) | 1.6 (0.9, 2.5) | 2.3 (1.5, 3.5) | 4.3 (2.9, 6.1) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary artery compliance (ml/m2/mmHg) | 2.3 (1.7, 3.1) | 1.6 (1.2, 2.2) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.4) | <0.001 |

| Aortic systolic pressure (mmHg) | 117 (103, 136) | 116 (100, 133) | 116 (102, 133) | 0.32 |

| Aortic pressure (mean) (mmHg) | 74 (66, 86) | 77 (67, 87) | 78 (69, 88) | 0.001 |

| Cardiac index (L/min/m2) | 2.0 (1.7, 2.4) | 2.0 (1.7, 2.5) | 1.9 (1.6, 2.4) | 0.052 |

Data shown as n (%) or mean ± SD or median (1st, 3rd quartiles).

Continuous variables were compared using ANOVA for means or Kruskal–Wallis test for medians. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate.

PVR = [(mean PA pressure – mean PCWP) / cardiac output].

PAC (pulmonary artery compliance) = stroke volume index (echo) / pulmonary artery pulse pressure where pulmonary artery pulse pressure is PA systolic pressure – PA diastolic pressure.

Clinical outcomes at 30 days and 1 year

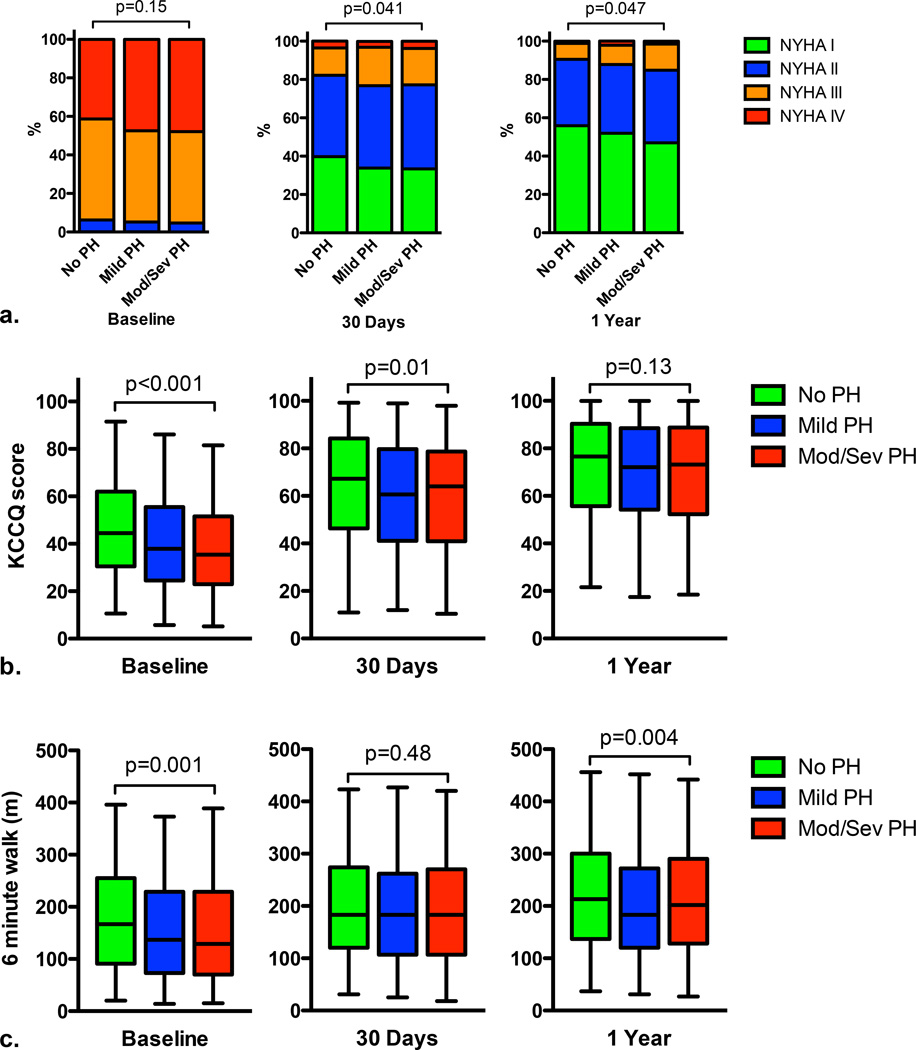

Higher pulmonary artery pressure was associated with a trend toward increased cardiovascular death (p=0.051) and stroke (p=0.052) at 30 days, but not with other clinical outcomes (Table 2). One-year rates of all-cause death, cardiovascular death, repeat hospitalization, and stroke were higher in those with a higher pulmonary artery pressure (p<0.05 for all) (Table 2). Although there were no differences in baseline NYHA functional class among PH groups, NYHA functional class was modestly worse at 30 days and 1 year in those with higher pulmonary artery pressures (Figure 1a). Initially, health status was worse among patients with higher pulmonary artery pressures, but by 1 year these differences were no longer observed (Figure 1b). At baseline, those with mild PH or moderate/severe PH walked 20 meters less in 6 minutes that those without PH (p≤0.005 for both), but at 30 days there was no difference in 6 minute walk distance between PH groups (Figure 1c). At 1 year, there was a difference in 6 minute walk distance between PH groups (p=0.008) owing to a shorter 6 minute walk distance among those with mild PH compared to those without PH (p=0.002) (Figure 1c).

Table 2.

Clinical Outcomes Based on Pulmonary Hypertension

| No PH % (no.) |

Mild PH % (no.) |

Mod/Sev PH % (no.) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 Days | ||||

| Death (all-cause) | 39 (5.0%) | 42 (5.0%) | 38 (6.8%) | 0.26 |

| Death (cardiac) | 22 (2.8%) | 31 (3.7%) | 30 (5.4%) | 0.051 |

| Repeat hospitalizations | 42 (5.5%) | 58 (7.2%) | 41 (7.7%) | 0.26 |

| Stroke (any) | 16 (2.1%) | 25 (3.0%) | 24 (4.4%) | 0.052 |

| Bleeding (major) | 71 (9.1%) | 78 (9.4%) | 48 (8.7%) | 0.92 |

| Vascular complications (major) | 66 (8.4%) | 57 (6.8%) | 41 (7.4%) | 0.47 |

| Renal failure (dialysis required) | 17 (2.2%) | 30 (3.6%) | 14 (2.6%) | 0.20 |

| 1 Year | ||||

| Death (all-cause) | 144 (18.6%) | 189 (22.7%) | 138 (25.0%) | 0.01 |

| Death (cardiac) | 47 (6.3%) | 77 (9.7%) | 67 (12.7%) | <0.001 |

| Repeat hospitalizations | 124 (17.3%) | 148 (19.4%) | 118 (23.8%) | 0.02 |

| Stroke (any) | 23 (3.0%) | 42 (5.4%) | 32 (6.1%) | 0.02 |

Data based on Kaplan Meier estimates.

P-value is from the log-rank test.

Figure 1. Functional classification, health status, and 6 minute walk distance over time according to severity of pulmonary hypertension.

New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class (a), Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) overall summary score (b), and 6 minute walk distance (c) at different time points according to the severity of pulmonary hypertension (PH). The box and whisker plots show the median values, 25th and 75th percentiles (box), and the 2.5 and 97.5 percentiles (whiskers).

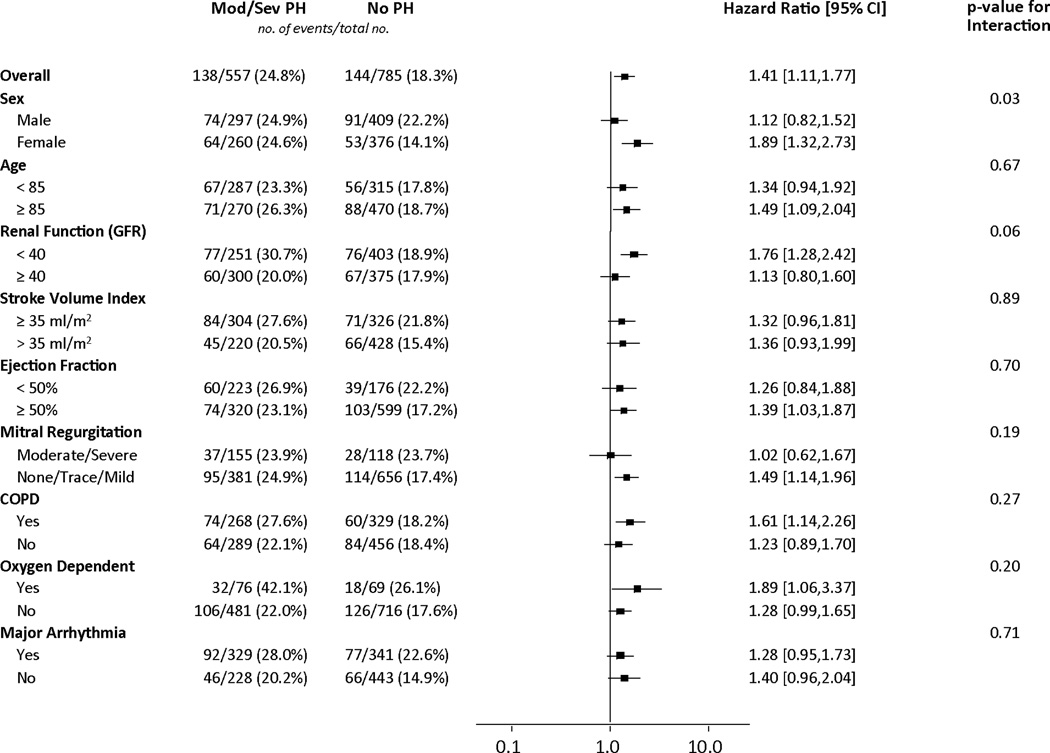

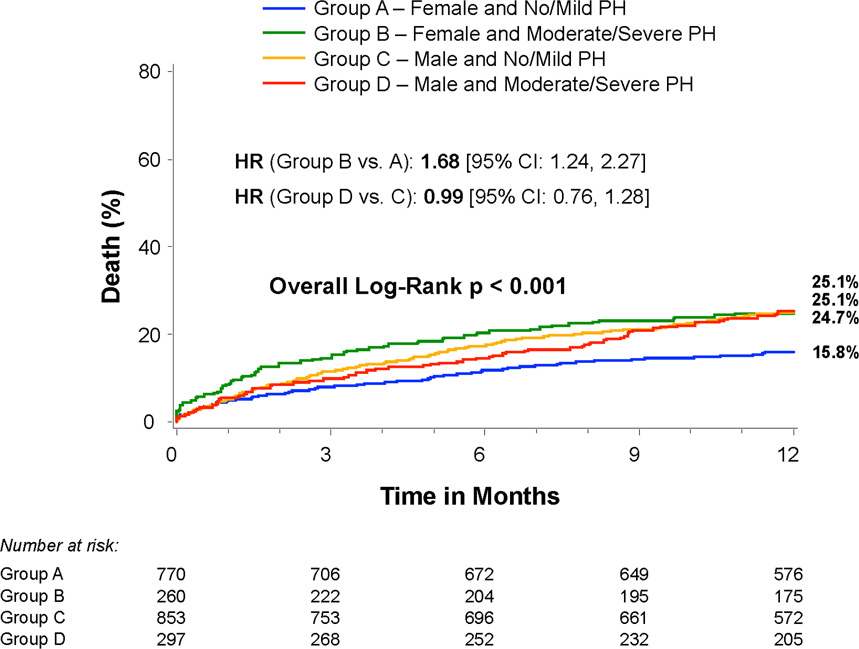

PH, mortality, and sex

We evaluated whether the increased hazard of death associated with moderate/severe PH (compared to no PH) was consistent across sub-groups. In females, moderate/severe PH was associated with increased mortality, whereas in males it was not (interaction p=0.03) (Figures 2 and 3). This interaction persisted after adjustment for factors associated with mortality (p=0.02) (Table 3). In adjusted analyses, females with moderate/severe PH had an increased hazard of death at 1 year compared to females without PH (adjusted HR 2.14, 95% CI 1.44–3.18) whereas those with mild PH did not (Table 3). Among males, there was no increased hazard of death associated with any severity of PH. Among patients with no or mild PH, males had an almost 2-fold higher adjusted hazard of death at 1 year, whereas there was no difference in mortality based on sex among those with moderate/severe PH (Table 3).

Figure 2. Effect of clinical and echocardiographic factors on the association between moderate or severe pulmonary hypertension and 1-year death from any cause.

Cox proportional hazards models were used to evaluate the hazard ratios for 1-year death from any cause for patients with moderate/severe versus no pulmonary hypertension in the clinical and echocardiographic sub-groups shown.

Abbreviations: GFR, glomerular filtration rate; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Figure 3. Sex, pulmonary hypertension, and mortality.

Time-to-event curves for all-cause death for risk scores based on sex and severity of pulmonary hypertension (PH). The event rates were calculated with the use of Kaplan-Meier methods and compared with the use of the log-rank test.

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis evaluating the relationship between sex, pulmonary hypertension, and 1-year all-cause mortality.

| Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|

| Sex * PH Severity | Interaction p=0.02 |

| Hazard for Mortality for PH According to Sex | |

| Males | |

| Mild PH vs. No PH | 1.22 (0.91, 1.63) |

| Moderate/severe PH vs. No PH | 1.15 (0.82, 1.60) |

| Females | |

| Mild PH vs. No PH | 1.23 (0.83, 1.83) |

| Moderate/severe PH vs. No PH | 2.14 (1.44, 3.18) |

| Hazard for Mortality for Males According to PH Severity | |

| Male vs. female (No PH) | 1.93 (1.34, 2.80) |

| Male vs. female (Mild PH) | 1.91 (1.38, 2.65) |

| Male vs. female (Moderate/Severe PH) | 1.04 (0.72, 1.49) |

Cox proportional hazards models evaluating variables associated with 1-year all-cause death among all patients (n=2180) prior to TAVR. Variables included were forced (age) or had a univariable association (p<0.10) with 1-year all-cause death (sex, cohort A vs. B, transfemoral vs. transapical, body mass index, STS score, oxygen dependent lung disease, frailty, major arrhythmia, permanent pacemaker, glomerular filtration rate, hemoglobin, left ventricular ejection fraction, aortic mean gradient, and ability to perform a 6 minute walk).

Mortality among patients with moderate/severe PH

We evaluated which clinical and hemodynamic factors were associated with mortality within the group of patients with moderate/severe PH (n=557). Among clinical factors with a univariable association with mortality, oxygen dependent lung disease (HR 2.57, 95% CI 1.63–4.06, p<0.001), lower glomerular filtration rate (HR 1.07 per 5 ml/min/1.73m2 decrease, 95% CI 1.01–1.14, p=0.03], lower aortic mean gradient (HR 1.07 per 5mmHg decrease, 95% CI 1.00–1.15, p=0.039), and inability to perform a 6 minute walk (HR 1.66, 95% CI 1.15–2.39, p=0.007) were independently associated with increased 1 year mortality (Table 4). After adjustment for clinical factors, none of the hemodynamic indices were associated with mortality although there was a trend of an association between lower pulmonary artery compliance and increased mortality (p=0.07) (Table 4). Although not a baseline variable that could be used in pre-operative risk stratification, moderate/severe total AR on the discharge echocardiogram was associated with increased 1 year mortality among patients with moderate/severe PH (adjusted HR 1.95, 95% CI 1.51–2.54, p<0.001).

Table 4.

Multivariable analysis evaluating variables associated with 1-year mortality among those with moderate or severe PH.

| Variable | Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Variables | ||

| Age | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | 0.48 |

| Male sex | 1.19 (0.82, 1.74) | 0.36 |

| Body mass index | 1.01 (0.97, 1.04) | 0.63 |

| STS score | 1.00 (0.95, 1.04) | 0.86 |

| Oxygen dependent lung disease | 2.57 (1.63, 4.06) | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1.46 (1.00, 2.14) | 0.052 |

| Major arrhythmia | 1.33 (0.91, 1.95) | 0.14 |

| Glomerular filtration rate (per 5 mL/min/1.73m2 decrease) | 1.07 (1.01, 1.14) | 0.03 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) (per 1 g/dL decrease) | 1.09 (0.97, 1.22) | 0.16 |

| Transfemoral approach | 0.81 (0.56, 1.15) | 0.24 |

| Aortic valve mean gradient (per 5 mmHg decrease) | 1.07 (1.00, 1.15) | 0.039 |

| 6 minute walk (could not perform) | 1.66 (1.15, 2.39) | 0.007 |

| Hemodynamic Variables (each evaluated separately and adjusted for the clinical variables above) | ||

| PA systolic pressure (per 5 mmHg increase) | 1.04 (0.97, 1.12) | 0.29 |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance (per 1 WU increase) | 1.04 (0.98, 1.11) | 0.22 |

| Pulmonary artery compliance (per 0.1 ml/m2/mmHg decrease) | 1.03 (1.00, 1.06) | 0.07 |

| Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (per 5 mmHg increase) | 1.01 (0.91, 1.11) | 0.92 |

| Right atrial pressure (per 5 mmHg increase) | 1.05 (0.92, 1.20) | 0.43 |

| Pulmonary artery pulse pressure (per 5 mmHg increase) | 1.03 (0.95, 1.11) | 0.46 |

| Stroke volume index (≤35 vs. >35 ml/m2) | 1.31 (0.89, 1.92) | 0.17 |

| Pulmonary artery systolic pressure / Aortic systolic pressure (per 0.05 increase in ratio) | 0.97 (0.91, 1.04) | 0.38 |

Cox proportional hazards models evaluating variables associated with 1-year all-cause death among patients with moderate or severe PH (n=557) prior to TAVR. Variables included were forced (age, sex) or had a univariable association (p<0.10, allowing for a weaker association than the “statistically significant” threshold of p<0.05) with 1-year all-cause death.

Pulmonary artery compliance = stroke volume index (echo) / pulmonary artery pulse pressure.

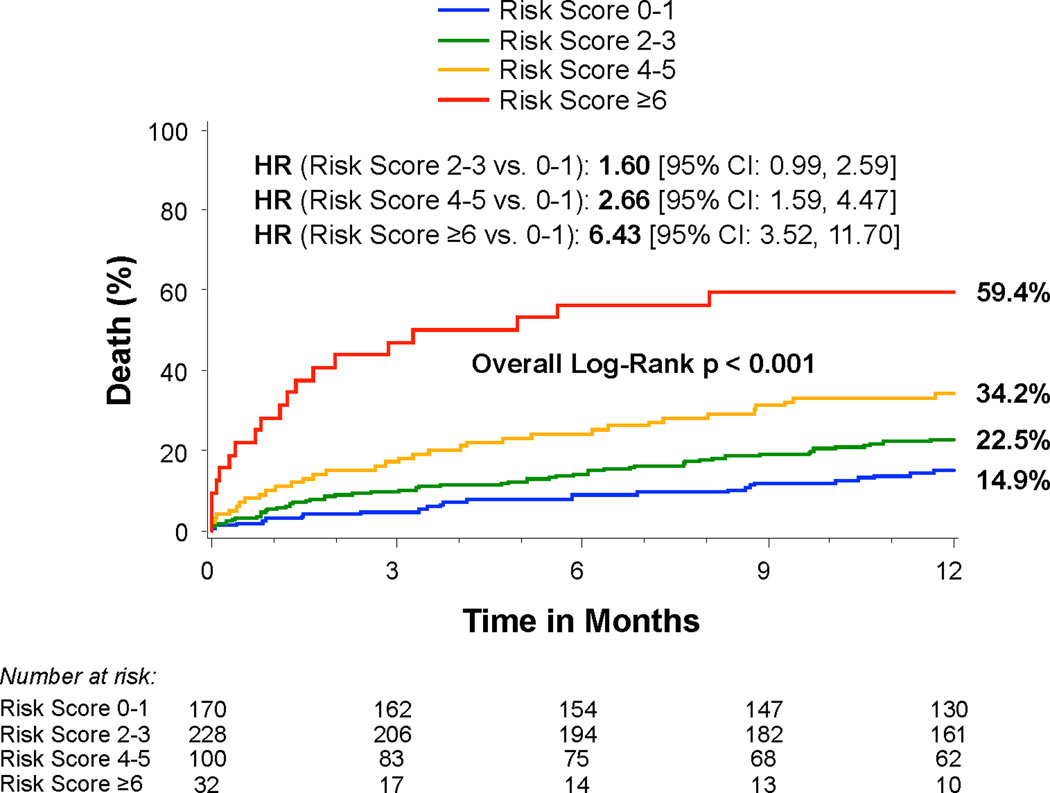

Based on this multivariable analysis of patients with moderate or severe PH, we developed a simple risk score (range 0–8) including oxygen dependent lung disease (3 points), glomerular filtration rate <40 ml/min/1.73m2 (2 points), inability to perform a 6 minute walk (2 points), and baseline aortic mean gradient <40 mmHg (1 point) (Online Table 1). The risk score had an AUC of 0.65 (95% CI 0.60–0.71) for 1-year death following TAVR. Based on an ROC-derived cut-point of ≥3 vs. <3, the risk score had a sensitivity of 62.8%, specificity of 59.4%, PPV of 33.2%, and NPV of 83.2% for 1-year death following TAVR. Among patients with moderate or severe PH and a low score (0–1), only 14.7% died by 1 year. In contrast, among those with a high score (6–8), 59.4% died by 1 year after TAVR (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Risk score and mortality among patients with moderate or severe pulmonary hypertension.

Time-to-event curves for all-cause death for risk scores 0–1, 2–3, 4–5, and ≥6. The event rates were calculated with the use of Kaplan-Meier methods and compared with the use of the log-rank test. The risk score was comprised of 4 variables with scale 0–8: oxygen dependent lung disease (3 points), glomerular filtration rate <40 (2 points), 6 minute walk (unable to perform) (2 points), and baseline transvalvular mean gradient <40 mmHg (1 point).

DISCUSSION

In patients with symptomatic AS at high or prohibitive surgical risk treated with TAVR, we found that increased pulmonary pressures are associated with increased mortality, more frequent repeat hospitalizations, and more strokes during the first year after the procedure. The increased hazard of mortality associated with moderate/severe PH was observed in females but not males. Hemodynamic factors were not helpful in further risk stratifying patients with moderate/severe PH. In contrast, clinical factors including oxygen dependent lung disease, inability to perform a 6 minute walk, worse renal function, and lower aortic mean gradient were independently associated with increased mortality after TAVR in patients with moderate/severe PH. A weighted combination of these factors was able to identify patients with a 15% versus 59% 1-year mortality. Further studies are needed to confirm and extend these findings to refine risk stratification of high-risk patients with significant PH evaluated for TAVR as this may have important implications for treatment decisions.

Pulmonary hypertension is more common than often recognized in patients with AS, present in up to 65% of patients with severe symptomatic AS.[1 16 17] Exercise induced pulmonary hypertension is present in over half of patients with severe asymptomatic AS and associated with increased cardiac events.[18] A significant proportion of patients with pulmonary hypertension have an elevated PVR, which further drives up the pulmonary pressures beyond those with only passive pulmonary venous hypertension.[7 17] Several studies have demonstrated the increased hazard of mortality associated with pulmonary hypertension in patients with AS treated with surgical valve replacement or TAVR.[1–4] Some patients with severe PH are turned down for surgery, which has a dismal prognosis.[19] Although pulmonary pressures tend to decrease after aortic valve replacement, some patients with severe pre-operative PH have a persistent severe elevation in pulmonary pressures post-operatively, which is associated with a higher mortality than if the pulmonary pressures decrease.[20] Given the increased hazard of death associated with significant PH, there is sometimes uncertainty in high risk patients referred for TAVR regarding anticipated clinical benefit from valve replacement.[5] Our findings confirm and extend prior studies in this area by identifying an interaction between PH and sex with respect to mortality after TAVR and identifying clinical factors as more important in risk stratifying patients with significant PH than hemodynamic factors.

Sex and PH

A novel finding from our study was the interaction between PH severity and sex with respect to mortality. The increased hazard of death associated with moderate/severe PH was only observed in females. Importantly, however, females with moderate/severe PH did not have worse outcomes than males. Rather, females with no or mild PH had much better survival than males and only when the PH was moderate or severe were outcomes similar between the sexes. Why was an increase in pulmonary artery pressures associated with increased mortality among females, but not males? In light of the numerous studies demonstrating an association between increasing pulmonary pressures and increased mortality after aortic valve replacement, the lack of this association in males is the more unexpected finding. Given the age of this patient cohort, hormonal differences are an unlikely explanation. Unlike pulmonary arterial hypertension which has a female predominance, we did not observe any association between sex and PH severity (Table 1). Perhaps other clinical factors are more powerful drivers of mortality in males such that the adverse effects of PH are diluted by other contributing factors. Further studies are needed to confirm this interaction between PH and sex with respect to mortality and elucidate mechanisms for it.

Hemodynamic Indices Not Helpful in Risk Stratification

When evaluating a patient with valvular heart disease and significant PH, there may be uncertainty regarding whether the proposed valve procedure will yield the desired symptomatic and functional benefit, which is often related to whether the PH is thought to be “reversible”.[5] The severity of elevation in PVR and perhaps the decline in pulmonary pressures or PVR after the administration of a vasodilator may be interpreted as suggesting the reversibility of the PH and likelihood of clinical benefit from a mitral or aortic valve procedure.[6 7] However, the specific drug used in this “vasodilator challenge” may influence the hemodynamic response, and data are lacking regarding the conclusions to be drawn about the anticipated clinical benefit of valve surgery based on pre-operative PVR elevation or vasodilator responsiveness.[8 21 22] Our study did not evaluate acute pre-TAVR reversibility of PH or elevated PVR or the change in pulmonary pressures over time after TAVR. However, our observations de-emphasize the importance of hemodynamic indices in further risk stratifying patients with significant PH being evaluated for TAVR. Interestingly, of all hemodynamic indices evaluated, pulmonary artery compliance (as an index of vascular stiffness) appeared to have greater prognostic utility than other measurements, which is consistent with studies in pulmonary arterial hypertension cohorts.[23]

Clinical implications

All patients with significant PH should not be considered alike in terms of the risk of adverse post-TAVR clinical outcomes. Rather than focusing on ways to risk stratify these patients based on hemodynamics, clinical factors appear to be more helpful in predicting mortality. Accordingly, instead of trying to risk stratify based on more detailed assessment of the pulmonary vasculature, it is more helpful to put the PH in the context of other organ dysfunction, including the lungs, kidneys, and cardiac performance. The constellation of factors in the clinical risk score identify those at particularly high risk for a poor outcome. When none/few of these factors were present, 1-year mortality was low (15%), whereas 1-year mortality was quite high (59%) when multiple factors were present, which may indicate the futility of TAVR in these patients. Among those with significant PH pre-operatively, the clinical impact of persistent significant PH versus resolution/reduction of PH after TAVR requires further study as does the potential benefit of PH-directed therapy (eg. phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors) in these patients.[7]

Limitations

These findings apply to older patients with symptomatic AS at high surgical risk and may not translate to younger, lower risk patients. We did not have echocardiographic measurements of pulmonary pressures at baseline or during follow-up, so we were unable to evaluate the effect of post-TAVR PH on clinical outcomes. The pulmonary pressures utilized in this study were obtained during the TAVR procedure (albeit prior to valvuloplasty or valve implantation) when patients were under general anesthesia, likely lowering the pressures. However, invasive hemodynamics are more accurate than those obtained by an echocardiogram and anesthesia was likely to affect patients in the study similarly. We did not have the heart rate recorded at the time of the invasive hemodynamics, so we had to use the stroke volume obtained on the baseline echocardiogram to calculate pulmonary arterial compliance. This method has shortcomings in the presence of concomitant regurgitant lesions of the mitral and aortic valves. Measurements of right ventricular function were not obtained in the PARTNER I cohort, which prevented us from looking at right ventricular – pulmonary arterial coupling in this study. Finally, the risk score reported for mortality has not been validated and only applies to patients with moderate or severe PH according to an invasive measurement of pulmonary artery pressure. Our purpose was not to develop a widely utilized risk score, but simply to demonstrate the broad range of outcomes in patients with moderate or severe PH based on the presence of these particular clinical factors.

Conclusion

PH is associated with lower survival after TAVR. Among those with moderate or severe PH, clinical factors are helpful in risk stratification, whereas hemodynamic factors appear to be less informative. TAVR may be futile for patients with significant PH with concomitant oxygen dependent lung disease, impaired renal function, mobility impairment, and low aortic valve gradients. Further studies are needed to elucidate the relationship between PH and sex with respect to mortality after TAVR, the effect of post-TAVR PH on clinical outcomes, and whether PH-targeted therapies might improve clinical outcomes in these higher risk patients.

Supplementary Material

STUDY SUMMARY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What is already known about this subject?

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is associated with increased mortality after surgical or transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) for aortic stenosis.

What does this study add?

This study indicates that clinical factors are more helpful than hemodynamic indices in stratifying risk among patients with moderate or severe PH evaluated for TAVR. A weighted combination of clinical factors was able to identify patients with a 15% versus 59% 1-year mortality. Moreover, the association between moderate/severe PH and increased mortality after TAVR was only observed in females.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

TAVR may be futile for patients with significant PH with concomitant oxygen dependent lung disease, impaired renal function, mobility impairment, and low aortic valve gradients. Further studies are needed to elucidate the relationship between PH and sex with respect to mortality after TAVR, the effect of post-TAVR PH on clinical outcomes, and whether PH-targeted therapies might improve clinical outcomes in these higher risk patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Maria Alu for her assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

Dr. Lindman is a site co-investigator for the PARTNER Trial and has received a research grant and serves on the scientific advisory board for Roche Diagnostics. Dr. Zajarias is a member of the PARTNER Trial Steering Committee, site PI for the PARTNER Trial, and a consultant for Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Miller has received has received consulting fees/honoraria from Abbott Vascular, St. Jude Medical, and Medtronic and is an unpaid member of the PARTNER Trial Executive Committee. Dr. Suri is a member of the Steering Committees of the COAPT Trial (Abbott Vascular) and the PORTICO Trial (St. Jude), national PI of the PERCEVAL Trial (Sorin Medical), has patent applications with Sorin, and has received research grants from Sorin, Edwards, Abbott, and St. Jude. Dr. Webb is a consultant for Edwards Lifesciences and an unpaid member of the PARTNER Trial Executive Committee. Dr. Svensson holds equity in Cardiosolutions and ValvXchange, and has Intellectual Property Rights/Royalties from Posthorax and is an unpaid member of the PARTNER Trial Executive Committee. Dr. Kodali has received consulting fees from Edwards Lifesciences and is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of Thubrikar Aortic Valve. Dr. Thourani is a member of the PARTNER Trial Steering Committee and a consultant for Edwards Lifesciences, Sorin Medical, St. Jude Medical, and DirectFlow. Dr. Lim has received consulting fees from Boston Scientific Corporation, Guerbet, and St. Jude Medical. Dr. Leon and Dr. Mack are unpaid members of the PARTNER Trial Executive Committee.

Funding: The PARTNER trial was funded by Edwards Lifesciences and the protocol was designed collaboratively by the Sponsor and the Steering Committee. The present analysis was carried out by academic investigators through the PARTNER Publications Office with no direct involvement of the sponsor in the analysis, drafting of the manuscript, or the decision to publish. Dr. Lindman is supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant number K23 HL116660].

Footnotes

Competing interests: The other authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Melby SJ, Moon MR, Lindman BR, et al. Impact of pulmonary hypertension on outcomes after aortic valve replacement for aortic valve stenosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141(6):1424–1430. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lucon A, Oger E, Bedossa M, et al. Prognostic implications of pulmonary hypertension in patients with severe aortic stenosis undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation: study from the FRANCE 2 registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7(2):240–247. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.113.000482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodes-Cabau J, Webb JG, Cheung A, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation for the treatment of severe symptomatic aortic stenosis in patients at very high or prohibitive surgical risk: acute and late outcomes of the multicenter Canadian experience. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(11):1080–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tamburino C, Capodanno D, Ramondo A, et al. Incidence and predictors of early and late mortality after transcatheter aortic valve implantation in 663 patients with severe aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2011;123(3):299–308. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.946533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holmes DR, Jr, Mack MJ, Kaul S, et al. 2012 ACCF/AATS/SCAI/STS expert consensus document on transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(13):1200–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahoney PD, Loh E, Blitz LR, et al. Hemodynamic effects of inhaled nitric oxide in women with mitral stenosis and pulmonary hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87(2):188–192. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01314-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindman BR, Zajarias A, Madrazo JA, et al. Effects of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibition on systemic and pulmonary hemodynamics and ventricular function in patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2012;125(19):2353–2362. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.081125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoeper MM, Barbera JA, Channick RN, et al. Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment of non-pulmonary arterial hypertension pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(1 Suppl):S85–S96. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(17):1597–1607. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, et al. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic-valve replacement in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(23):2187–2198. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Douglas PS, Waugh RA, Bloomfield G, et al. Implementation of echocardiography core laboratory best practices: a case study of the PARTNER I trial. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2013;26(4):348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hahn RT, Pibarot P, Stewart WJ, et al. Comparison of Transcatheter and Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement in Severe Aortic Stenosis: A Longitudinal Study of Echocardiography Parameters in Cohort A of the PARTNER Trial (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(25):2514–2521. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnold SV, Spertus JA, Lei Y, et al. Use of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire for monitoring health status in patients with aortic stenosis. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(1):61–67. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.970053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reynolds MR, Magnuson EA, Lei Y, et al. Health-related quality of life after transcatheter aortic valve replacement in inoperable patients with severe aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2011;124(18):1964–1972. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.040022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reynolds MR, Magnuson EA, Wang K, et al. Health-related quality of life after transcatheter or surgical aortic valve replacement in high-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis: results from the PARTNER (Placement of AoRTic TraNscathetER Valve) Trial (Cohort A) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(6):548–558. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.03.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faggiano P, Antonini-Canterin F, Ribichini F, et al. Pulmonary artery hypertension in adult patients with symptomatic valvular aortic stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2000;85(2):204–208. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)00643-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ben-Dor I, Goldstein SA, Pichard AD, et al. Clinical profile, prognostic implication, and response to treatment of pulmonary hypertension in patients with severe aortic stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107(7):1046–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lancellotti P, Magne J, Donal E, et al. Determinants and prognostic significance of exercise pulmonary hypertension in asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2012;126(7):851–859. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.088427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malouf JF, Enriquez-Sarano M, Pellikka PA, et al. Severe pulmonary hypertension in patients with severe aortic valve stenosis: clinical profile and prognostic implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40(4):789–795. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinning JM, Hammerstingl C, Chin D, et al. Decrease of pulmonary hypertension impacts on prognosis after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. EuroIntervention. 2014;9(9):1042–1049. doi: 10.4244/EIJV9I9A177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galie N, Hoeper MM, Humbert M, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS), endorsed by the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Eur Heart J. 2009;30(20):2493–2537. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melenovsky V, Al-Hiti H, Kazdova L, et al. Transpulmonary B-type natriuretic peptide uptake and cyclic guanosine monophosphate release in heart failure and pulmonary hypertension: the effects of sildenafil. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(7):595–600. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahapatra S, Nishimura RA, Sorajja P, et al. Relationship of pulmonary arterial capacitance and mortality in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(4):799–803. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.