Abstract

Background

Homeless patients face unique challenges in obtaining primary care responsive to their needs and context. Patient experience questionnaires could permit assessment of patient-centered medical homes for this population, but standard instruments may not reflect homeless patients' priorities and concerns.

Objectives

This report describes (a) the content and psychometric properties of a new primary care questionnaire for homeless patients and (b) the methods utilized in its development.

Methods

Starting with quality-related constructs from the Institute of Medicine, we identified relevant themes by interviewing homeless patients and experts in their care. A multidisciplinary team drafted a preliminary set of 78 items. This was administered to homeless-experienced clients (n=563) across 3 VA facilities and 1 non-VA Health Care for the Homeless Program. Using Item Response Theory, we examined Test Information Function curves to eliminate less informative items and devise plausibly distinct subscales.

Results

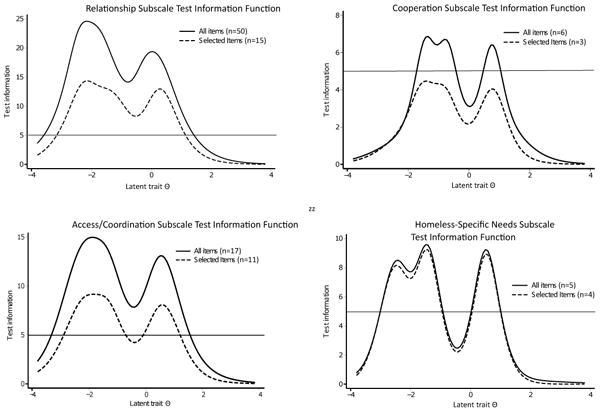

The resulting 33-item instrument (Primary Care Quality-Homeless, PCQ-H) has four subscales: Patient-Clinician Relationship (15 items), Cooperation among Clinicians (3 items), Access/Coordination (11 items) and Homeless-Specific Needs (4 items). Evidence for divergent and convergent validity is provided. Test Information Function (TIF) graphs showed adequate informational value to permit inferences about groups for 3 subscales (Relationship, Cooperation and Access/Coordination). The 3-item Cooperation subscale had lower informational value (TIF<5) but had good internal consistency (alpha=0.75) and patients frequently reported problems in this aspect of care.

Conclusions

Systematic application of qualitative and quantitative methods supported the development of a brief patient-reported questionnaire focused on the primary care of homeless patients and offers guidance for future population-specific instrument development.

Introduction

On a single winter night in 2013, 610,042 Americans were counted as homeless, including 57,849 US military veterans,1a numberconsiderably higher when homelessness is counted over the year.2The vulnerability of homeless individuals is reflected inexcess mortality,3-6 hospital utilization,7,8 and poor health.9 Their access to health care is typically poor,10-12and they often feel unwelcome in care.13Programmatic efforts to remediate access barriersbegan with Health Care for the Homeless Programs, first supported by private foundations and then by the US Department of Health and Human Services.14In recent years, the US Department of Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) initiated 38 homeless-focused primary care programs.15High quality primary care for homeless persons could, in principle, ameliorate disparitiesand produce cost offsets elsewhere (e.g., fewer emergency room visits, hospitalizations), and perhapscontribute to the reduction of homelessness.16

Assessing the provision of high quality primary care for homeless persons faces challenges ofoperationalization and measurement. Single-disease performance metricscan beproblematicin their application to special or multi-morbid populations and in situations where the context of care should influence decision-making.17-19Patient-centric approaches to primary care have gained in popularity, including Patient Centered Medical Homes (PCMHs)and the VA's Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACTs).20These changes in care delivery havecontributedto increased interest inpatient assessments of care and team-based care,21and whether care approximates priorities identified by expert consensus groups (i.e., Institute of Medicine (IOM)). Relatively little is known about homeless patients' perceptions of key aspects of care such as accessibility, continuity, coordination, principlesenshrined in the Consumer Assessment of Health Plans (CAHPS)22 and the Primary Care Assessment Survey (PCAS).23

Administration of the CAHPSwith PCMH itemsis required of federal Health Care for the Homeless programs seeking PCMH status,and CAHPS items are now used within VA's Survey of Health Experiences of Patients.23-25 These surveysare potentially problematic in application to homeless patients. The CAHPS presents 43 questions (1012 words) at a 9th grade reading level.26 Twelve items are used to implement skips among the remaining 31 items, and 7 different response sets are used. For clients who are ill-rested or cognitively impaired, the risk of error or overload may be high. Questions maypresuppose conditions and expectations that may not apply. More pressingly,specific concerns and aspirations important to homeless patients are likely to differ from theconcepts queried in standard instruments, including the pressure to balancehealth care against competing demands,27 perceptions of being unwelcome or adversely judged,13,28,29 mutual mistrust, and other unique constraints.30

These concerns spurred development of a patient-reported primary care assessment instrumentspecifically designed to assess homeless patients' experiences in primary care, applicable in VA and non-VA settings alike.The purposes of thisreportwere twofold: to portray the process and psychometrics supporting a new survey toolfocused on primary care for homeless individuals; and to provide a portrait of the combined qualitative and quantitative procedures that can support the development of patient-reported care surveys for patient populations with unique concerns and needs.

Methods

Themethod of instrument developmentproceeded fromthree assumptions about measurement of patient care in a homeless population.First, generalconstructsrelevant to quality ought to derive fromthe IOM's definition of primary care31 and its Rules for Quality.32Thisapproach was embracedby the PCAS23 and the Primary Care Assessment Tool (PCAT).33Second, homeless patients' needs and concerns are unique,requiring qualitative inquiry to guide item development.13,34 Third, to validate the results from these assumptions, the final instrument had to demonstrate adequate psychometric properties.Based on these assumptions, we sought to develop an instrumentthat was both sensitive to homeless patients' concerns and practicalfor administrationin resource-constrained clinical settings such as Federally-Qualified Health Centers and volunteer clinics, in addition to more standard primary care and research contexts. The specific steps involved in the development of the instrument are detailed below and outlined graphically in Supplemental Digital Content Figure 1, Supplimental Digital Content 1 http://links.lww.com/MLR/A742 .

1. Preliminary identification of constructs

Two reports from the IOM were used to preliminarily identify 16constructs potentially appropriate for inquiry, with the expectation that these constructs would form the basis of subscales in the final instrument. These included the IoM's“Ten Rules for Quality”32and elements from the IoM's definition of primary care.31They include general concepts such as care being accessible and characterized by evidence-based decision-making.

2. Prioritization of constructs for inclusion

A cardsort ranking exercise was used to narrow the 16 preliminaryconstructs to 8, a numberaddressable in qualitative interviews,described elsewhere.35Briefly, each of the constructs was restated in simple declarative form (e.g. the IoM priority ofaccessibility was “Primary care should be easy to get”). Patients (n=26)from homeless service settings and experts in homeless health care(n=10) were asked to sort the cards with their highest priority at top(Supplemental Digital Content Table 1,supplementary Digital Content 2 http://links.lww.com/MLR/A743 . provides the working definition for each of the eight constructs emergent from this exercise).

3. Qualitative interviews

Based on the 8 prioritized constructs, semi-structured qualitative interviews were used to identify key themes for question content, supplemented by 4focus groups to confirm themes related to unanticipated constructs that emerged from the interviews.Patient intervieweeswere recruited from a non-VA Health Care for the Homeless Program(n=20)36 and from a VA hospital(n= 16). Additionally, 24 interviews were obtained from homeless care provider/experts (clinicians, administrators, and homeless researchers) from North America. Recruitment intentionallybalancedveteran-focused with non-veteran focused interviewees and frontline clinicians withresearchers and program leaders. While patient-level interviews occurred in person, experts were often interviewed by telephone.

The interviews used a semi-structured guide thatdiffered only slightly in the questions for patients and provider/experts.The typical qualitative interview prompt offered a brief, plain English restatement of the construct of interest using open-ended language to encourage new interpretations, including unanticipated constructs that might emerge. Thus a query related to “Care Based on Medical Evidence” was:

What do you think about the idea that your primary care should be based on the best medical knowledge?

Two follow-up probes were:

What makes you say that?

How about times when you didn't have a regular place to live? Did/does that make it different?

Interviewers were trained by a team of two experienced faculty (authors CH and DEP), including video-taped mock interviews, performance analysis, and feedback. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed. For both the qualitative interviews and the administration of PCQ-H version 1.0 reported below, participants underwent a structured informed consent with modest remuneration. All procedures were approved by Institutional Review Boards at all facilities involved with the study.

4. Qualitativeanalysis

Interviews were coded for themes toguide survey item development.The coding approach, Template Analysis37,38,begins withidentification ofconceptswithin the investigators' a priori framework (in this case the IoM constructs).39,40Coders workedindependently only after achieving inter-rater reliability of ≤75%.For each overarching construct, 3-8 themes emerged inductively, often with subsidiary subthemes. Three entirely new constructs emerged as well (trust, homeless-specific needs, substance abuse/mental illness), producing a total of 11 constructs of interest for the anticipated survey. Wereviewedall proposed themes, organizing and refining until consensus was reached.

5. Item generation

For each of the 11 constructs, 18-50 items were draftedbased on our review of the most evocative qualitative interview quotes pertinent to each construct.All items were reviewed by a multidisciplinary team, with backgrounds in homeless primary care delivery, social work, psychology, nursing, medicine, and survey design. A consensus voting processprioritized7 to 8 items per construct to provide a workable number for testing.The resulting 78 items underwent cognitive interviewing (n=12)to identify item interpretation problems. Only slight wording changes resulted from this exercise.

6. Administration for psychometric analysis and validation

The preliminary Primary Care Quality-Homeless survey(PCQ-H, version 1.0)included 78 items for11 constructs (Table 1).To simplify administration in resource-poor environments with low-literacy populations, the survey avoidedskips and applied a uniform 4-point Likert-type response (Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree, permitting “I don't know/no response” as an option). The survey was administered to 563 persons who used services at Health Care for Homeless Veterans programs at3VA facilities and 1 non-VA Health Care for the Homeless Program. Recruitment is detailedseparately but summarized here.41Eligibility was restricted to persons who had recorded evidence of past or current homelessness and2 or more visits to a primary care providerin the past 2 years.

Table 1. Description of the Primary Care Quality–Homeless Survey Development Sample.

| Characteristics | N = 563 |

|---|---|

| Age [mean (SD)] (y) | 53.2 (8.2) |

| Gender | |

| Female, % | 14.4 |

| Male, % | 84.9 |

| Transgender/other, % | 0.7 |

| Race | |

| African American, % | 57.7 |

| Native American, Asian, Pacific Islander, % | 2.1 |

| White, % | 30.6 |

| Other, % | 9.6 |

| Hispanic/Latino, % | 5.3 |

| Chronically homeless in past 3 years, % | 68.2 |

| Spent 1 or more nights in street, car, abandoned building, or emergency shelter, last 2 weeks, % | 12.1 |

| General health status is fair or poor, % | 42.9 |

| Psychiatric symptom intensity (Colorado Symptom Index), last 6 months* [mean (SD)] | 16.4 (11.2) |

| Any illicit drug use, past 3 months, % | 32.9 |

| Any alcohol use, past 3 months, % | 22.6 |

| Duration of primary care relationship >2 years, % | 56.4 |

The Colorado Symptom Index ranges from 0–56.

Two questionnaires were administeredfordivergent/convergent validity analyses. For divergent validity we projected weak or no correlation between the PCQ-H and scores from a construct that might represent a “rival hypothesis” for response patterns obtained; for this we used a short measure of distressing psychiatric symptoms validated in a large national homeless sample, the Colorado Symptom Index42 (the putative rival hypothesis: persons with psychological distress will give less favorable reports of primary care).For convergent validity, we used the PCAS, subject to the single-dimension scoring approachpublished by Roumie (α = 0.93).23,43

7. Item selection

Preliminary item reduction and scale collapsing

The resultsfromsurvey administration to a 563-person sample supported an item reduction exercise to minimizelength while exploring the statistical correlationof the 11 subscales. The intent of this process was to retain items that were informative across the range of the latent construct (a more or less favorable view of care with respect to the applicable subscale), and to avoid burdening respondents with correlated but fundamentallyredundant items (“bloated specific” scales44).

The steps to accomplish included a preliminary confirmatory factor analysis, but all subsequent work based on Item Response Theory (IRT). IRT offers advantages in shortening scales by separating consideration of informational value from item “difficulty”, i.e., the informational position along the dimension under study. While IRT pertains to a family of models, they share a common set of assumptionstermed unidimensionality and local independence.45Unidimensionality presumes item responses are dependent upon a single underlying dimension common to all items in the test. Local independence assumes that conditional upon the underlying common trait, item responses should be uncorrelated. Although local dependence and multidimensionality (i.e. violations of the core assumptions) are related, it is possible that pairs of items could be correlated after controlling for the underlying trait, e.g., through redundancy in content. However, this dependence is not sufficient or not shared among enough items to appear as multidimensionality (i.e., it is local to the item pair).

In our analysis, we approached the unidimensionality assumption by first subjecting our items to the preliminary confirmatory factor analysis, then performing IRT models on sub-sets of items identified as loading on individual factors. We approached local dependence by carefully reviewing preliminary IRT model results and scrutinizing items with high loadings and overlapping item characteristic curves for redundancy in content, removing items with high redundancy.

The item reduction process was as follows:

First, 5 items were dropped where >10% of respondents could not answer, leaving 73 items. Second, for a preliminary assessment of scale correlation, confirmatory factor analysis was applied to all73 items with factor loading based on the 11 hypothesized subscales/constructs, treating the items as ordered categories, using the Mplus default WLSMV estimation method.46While correlation between subscales is typical for patient questionnaires,23,24,47to avoid excessive correlation subscales were merged until no pairwise correlation exceeded 0.8 (resulting in 4 subscales). However, subsequent work on the PCQ-H was not based on factor analysis. IRT (two parameter graded response analysis48) was applied to identify items optimally discriminating acrossthe range of the latent trait. The model permits calculation of the informational value for each item, relative to the inferred construct. The modeling accounts for both discrimination (the strength of the association between the item and the construct) and location (where along the spectrum of the construct an item is most informative). The informational value of a collection of items is presented as a test information function (TIF) curve, with the x-axis representing variation in the latent construct and the y-axis the informational value of a set of items. It washypothesized that a minimum test information value of 5 permits inferences about groups, and 10 permits inferences about individuals (analogous to reliability of 0.8 and 0.9 respectively).49This portion of the analysis was conducted using the ltm package of the R programming environment.50

Fourth, at each step in IRT analysis,TIF curves were reviewed, with focus on TIF values in the active range (θ = -1.5 to + 1.5). Fifth, automated algorithms were applied to retain items of maximum informational value, leaving 14 items. Because the resultingTIF curves consistently fell below 5, items were reinserted based on criteria. These included (a)retaining items with unfavorable responses from>13% of respondents (a cutpoint selected empirically after reviewing the range of unfavorable percentages), (b)retaining the 2items most informative for each of original 11 constructs, and (c) removal of 3 items that wereverballyand statistically redundant with other items.

Sixth, in order to assure that the internal consistency of the PCQ-H subscales could be compared to other published instruments,51,52 the commonly-used Cronbach'sαwas computed for each subscale, where an optimum of 0.7 or 0.8 is considered desirable for inferences concerning groups.49Becauseα's known limitations,53 we also report McDonald's ωt.54Finally, in light of prior studies suggesting a single higher-order factor often fits response patterns obtained from patient experience questionnaires,43,47,55(permitting a single overall score with plausible fit to date 43), a single scale solution of all items was checked for adequacy.

Results

Construct Selection

From the cardsort exercise (step 2 above), the 8 most highly rated constructs targeted for qualitative interviewswere: Accountability, Integration/Coordination, Evidence-Based Decision-Making, Accessibility, Patient as the Source of Control, Cooperation among Clinicians, Continuous Healing Relationships, and Shared Knowledge and the Free Flow of Information. Additionally, 3 novel constructs emerged from qualitative interviews (Homeless-Specific Needs, Trust/Respect, Substance Abuse/Mental Illness). From themes emergent within these 11 constructs, 78 items were included in the development version of the PCQ-H.

Sample Characteristics

The sample of 563 persons administered the development version was racially diverse (58% Black, 31% White, 12% Other) with14% women (Table 1).Military service was common (71%); 65% of respondents were recruited from VA settings. Although all respondentshad a history of homelessness, few had sleptin shelters or on the streets in the preceding14 days(12%). However 65% had prior homelessness exceeding 1 year. All had ongoing primary care, with duration of care more than 2 years for56% of respondents.

Psychometric validation

Serial merging of highly correlated scales and subsequent re-specification resulted in 4 subscales that served as the basis for the subsequent item response analysis. The decision to merge hypothesized subscales where correlations were very high (r>0.8)meant that these 4 subscales varied in the number of retained items (Table 2). For example, the Patient-Clinician Relationship subscale (a combination of 7 hypothesized subscales)had 15 items, while the subscale reflecting perceptions of Cooperation among caregivers (derived from 1 hypothesized subscale) had 3 items.

Table 2. Primary Care Quality-Homeless (PCQ-H) Survey Items Organized by Subscale1,2.

| Subscales (Mean Score ± SD) | Unfavorable Response3 (%) | IRT Parameter Estimates | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | b1 | b2 | b3 | ||

| Patient-Clinician Relationship (3.3 ± 0.5) | |||||

| 1 My PCP never doubts my health needs. | 15 | 1.914 | -2.334 | -1.428 | 0.234 |

| 2 My PCP takes my health concerns seriously. | 15 | 3.781 | -2.330 | -1.828 | -0.289 |

| 3 My PCP makes decisions based on what will truly help me | 5 | 3.599 | -2.418 | -1.743 | -0.117 |

| 4 I feel my PCP has spent enough time trying to get to know me. | 17 | 2.965 | -2.304 | -1.108 | 0.167 |

| 5 I can get in touch with my PCP when I need to. | 23 | 1.835 | -2.201 | -1.040 | 0.653 |

| 6 I can get enough of my PCP's time if I need it. | 17 | 2.503 | -2.130 | -1.223 | 0.504 |

| 7 If my PCP and I were to disagree about something related to my care, we could work it out. | 6 | 2.792 | -2.417 | -1.719 | 0.358 |

| 8 My PCP makes sure health care decisions fit with the other challenges in my life. | 9 | 3.262 | -2.301 | -1.436 | 0.310 |

| 9 I worry about whether my PCP has the right skills to take good care of me. | 16 | 1.796 | -2.493 | -1.400 | 0.311 |

| 10 I can be honest with my PCP if I use drugs or alcohol. | 6 | 2.153 | -2.883 | -2.004 | 0.027 |

| 11 I worry my PCP might report my health information to the authorities. | 7 | 1.151 | -4.092 | -2.607 | 0.499 |

| 12 Someone from my PCP's office returns my phone calls or pages. | 10 | 1.617 | -2.762 | -1.806 | 0.825 |

| 13 When I need information about my health care, like test results, I can get it easily. | 9 | 1.752 | -3.121 | -1.778 | 0.659 |

| 14 The staff at this place listens to me. | 7 | 2.020 | -2.676 | -1.852 | 0.669 |

| 15 Staffs at this place treat some patients worse if they think that they have addiction issues. | 12 | 1.377 | -2.922 | -1.705 | 0.627 |

| Cooperation (2.9 ± 0.7) | |||||

| 16 My primary care and other health care providers need to communicate with each other more. | 45 | 2.038 | -1.510 | -0.158 | 1.400 |

| 17 I have been frustrated by lack of communication among my primary care and other health care providers. | 24 | 4.344 | -1.417 | -0.721 | 0.776 |

| 18 My primary care and other health care providers are working together to come up with a plan to meet my needs. | 15 | 1.687 | -2.498 | -1.363 | 0.663 |

| Access/Coordination (3.1 ± 0.5) | |||||

| 19 My PCP helps to reduce the hassles when I am referred to other services. | 11 | 2.246 | -2.542 | -1.423 | 0.552 |

| 20 I have to wait too long to get the health care services my PCP thinks I need. | 23 | 1.676 | -1.963 | -1.077 | 0.935 |

| 21 At this place, I have sometimes not gotten care because I cannot pay. | 4 | 1.200 | -4.522 | -3.049 | 0.132 |

| 22 If I could not get to this place, I think the staff would reach out to try to help me get care. | 14 | 2.438 | -2.050 | -1.218 | 0.685 |

| 23 If I walk-in to this place without an appointment, I have to wait too long for care. | 29 | 1.328 | -2.313 | -0.900 | 1.587 |

| 24 This place is open at times of the day that are convenient for me. | 6 | 2.258 | -2.710 | -1.878 | 0.494 |

| 25 This place helps me get care without missing meals or a place to sleep. | 11 | 2.682 | -2.273 | -1.361 | 0.528 |

| 26 It is often difficult to get health care at this place. | 7 | 2.331 | -2.596 | -1.691 | 0.358 |

| 27 This place tells me about what services are available. | 11 | 3.044 | -2.042 | -1.331 | 0.408 |

| 28 The health care services I need are close to each other. | 13 | 1.966 | -2.505 | -1.458 | 0.837 |

| 29 If my PCP is unavailable there is someone else that can help me. | 8 | 2.440 | -2.402 | -1.589 | 0.796 |

| Homeless-Specific Needs (3.1 ± 0.5) | |||||

| 30 This place tries to help me with things I might need right away, like food, shelter or clothing. | 11 | 3.353 | -2.228 | -1.328 | 0.494 |

| 31 The people who work at this place seem to like working with people who have been homeless. | 8 | 3.768 | -2.490 | -1.445 | 0.471 |

| 32 If I miss an appointment, this place still finds a way to help me. | 8 | 3.329 | -2.826 | -1.496 | 0.623 |

| 33 At this place, I always have to choose between health care and dealing with other challenges in my life. | 27 | 0.921 | -3.729 | -1.274 | 1.749 |

| Primary Care Quality-Homeless Overall Score (PCQ-H-33) ( 3.2 ± 0.4) | |||||

This tabular summary of items is not designed for direct administration in clinic settings. A version with complete introductory language, response options, and variable names is available from the authors. Response options ranged from strongly agree (value of 4) to strongly disagree (value of 1), with reverse-scoring applied to negatively worded items (items 9, 11, 15, 16, 17, 20, 21, 23, 26 and 33). Scoring for each subscale reflects computation of the mean obtained value among items available, provided at least 50% of items for each subscale have obtained a valid response.

2.2. Calculated indices of internal consistency/reliability (Crohnbach's α, McDonald's ωt) are as follows: Patient-Clinician Relationship (0.92, 0.96); Cooperation (0.75, 0.85); Access/Coordination (0.87, 0.94); Homeless-Specific Needs (0.76, 0.88).

The “unfavorable response” is present when an individual offered “Strongly Disagree”/“Disagree” for positively worded items or “Strongly Agree”/”Agree” for negatively worded items (items 9, 11, 15, 16, 17, 20, 21, 23, 26 and 33).

Given that survey items useda 4-point response scale, the mean scores (Table 2) reflect a general tendency for patients to tend toward favorable as opposed to unfavorable ratings, a pattern reported with most other primary care instruments.52,56The pairwise correlations among the 4 retained subscales (Table 3) remained substantial (r=0.51-0.78), though not different from the benchmark CAHPS Adult Core Survey.24

Table 3. Estimated Correlations among Primary Care Quality-Homeless Survey Subscales.

| Subscale | 1. Patient-Clinician Relationship | 2. Cooperation | 3. Access/Coordination |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Patient-Clinician Relationship | |||

| 2. Cooperation | 0.66 | ||

| 3. Access/Coordination | 0.78 | 0.65 | |

| 4. Homeless-Specific Needs | 0.66 | 0.51 | 0.69 |

Source: Responses to Primary Care Quality-Homeless Survey, N = 563.

The “active” range for a TIF curve refers to the area where most respondents fall with respect to the modeled traitθ (in our sample, typically–1.5 ≤ θ ≤ 1.5).TIF curves (Figures 1A – 1D)show that the informationalvaluemostly exceeded the desired optimumof 5 in the active range for the Relationship, Access/Coordination and Homeless-Specific Needs Subscales. Peaks and valleys in the TIF curves indicated that for each subscale, the variation in item responses was more informative at certain locations with respect to the modeled trait θ. Very broadly this reflected greater informational precision (and firmer inferences) where θ was frankly low and frankly high, and less information for middling levels of θ.

Figure 1.

Depiction of Test Information Function curves, by subscale, for the initial set of items field-tested (solid lines) and for the items selected after reduction (dotted lines). The “latent trait” θ refers to the underlying strength of satisfaction for the relevant trait, with θ for most persons falling between -1.5 and +1.5, with small numbers falling outside these bounds. For the Patient-Clinician Relationship subscale, 5.2% of respondents had latent trait value θ≤ -1.5, and 8.2% had θ≥ +1.5.For the (perceived) Cooperation subscale, 7.9% had latent trait value θ≤ -1.5, and 17% had θ≥ +1.0. For the Access/Coordination subscale, 2.5% had latent trait value θ≤ -1.5, and 8.7% had θ≥ +1.5.For the Homeless-specific needs subscale, 4.5% had latent trait value θ≤ -1.5 and 16% had θ≥ +1.0.

The initial TIF curve for Cooperation met the study criterion of TIF>5, but suffered from very redundant items (e.g. “My primary care and other health care providers are working together to come up with a plan to meet my needs” and “My health care is better because my primary care and other health care providers work together”). Three of the 6 items were dropped due to this semantic redundancy (withextremely correlated responses, r>0.7). The resulting subscale was not highly correlated with the other three, and obtained high levels of dissatisfaction (Table 2). The TIF curvefell below the optimum of 5 (see Figure 2D), butCronbach'sαwas acceptable at 0.75.

Within each subscale, internal consistency estimates were relatively high (Cronbach'sα= 0.92, 0.75, 0.87, 0.76 for Relationship, Cooperation, Access/Coordination, Homeless-Specific Needs), and α = 0.96 for single 33-item summative scale.

For a single factor solution, based on all 33 retained items, the TIF curve exceeded 20 across the active range (image not shown). All TIF curves fell below the criterion of 5 at the extremes, where very few respondents were located.

Convergent validity was robust. The overall PCQ-H score correlated with Roumie's single factor-derived score for thePCAS (r=0.73, p<.001).23,43There was extremely modest inverse correlation between psychiatric distress (Colorado Symptom Index) and overall PCQ-H score (r=−0.13, p=0.002), supportingdivergent validity.

The final Primary Care Quality-Homeless (PCQ-H) instrument included 33 items, with a 7th grade reading level (694 words).

Discussion

Challenges such as poor accessibility,57uncoordinated care,58 andfeeling unwelcome13 in care are not unique to persons who are homeless, but they areoftencrucial barriers to appropriate care. With increasing interest in population-tailored service delivery models, the PCQ-H instrumentshouldresonate for persons who have experienced homelessness. Questions regarding accessibility, for example, ask about outreach services, walking in for care (as opposed to telephoning for care, emphasized in the industry standard CAHPS), and payment barriers. Questions regarding patient-clinician relationship query matters of control, trust, respect, and perceptions of competence.

A substantialconceptual strength of our PCQ-H instrument lies in a development process that integrates2divergentsurvey development traditions that can be termeddeductive (“top down”) and inductive (“bottom up”) approaches. Specifically, foundational surveys (including PCAT and PCAS23,33)started withprinciples laid out by the IoM(including the notion that primary care be integrated, accessible, and continuous)31 followed by expert question design, subject later to cognitive response interviews, focus groups, and patient testing.While covering a range of expert-defined domains, this approach risks missing or underemphasizing constructs of concern to particular populations.

A contrasting “bottom up” tradition begins with qualitative inquiry among patients, exemplified by the Homeless Satisfaction with Care Scale (HSCS).59 The HSCS teamfirst queried“satisfaction” qualitatively. The resultant HSCS emphasizes respect, stigma and trust, although it does not query many experiential domains named by the IoM (e.g., continuity, coordination, cooperation). The PCQ-H, like the CAHPS, strives to query patient experiences (rather than the HSCS's “satisfaction”60). However, as with the HSCS, qualitative inquiry from patients determined what would be queried.

The resulting 33-item PCQ-H attainedcriteria for convergent and divergent validity. Additionally, criterion validity is suggested by the finding that PCQ-H scores are higher in settings that tailor primary care service design to meet the needs of homeless patients.41The informational value for each subscale varies. If one adheres to the optimum standards for IRT analysis, inferences about groups (TIF>5) can be made for all but the Cooperation subscale. Informational performance is strong enough to permit inference about individuals for the Relationship subscale and for the overall PCQ-H score (TIF>10).

A potential limitation is that the 3-item Cooperation subscale fell short of the optimum TIF>5 threshold. However the alpha of 0.75 is higher than that reported for 3 of the 5 scales finalized in the CAHPS 2.0 Adult Survey,24 higher than most α's computed for the CAHPS Patient Centered Medical Home instrument (0.61, 0.62, 0.68, 0.74, 0.85 and 0.91),61 and within the range of those reported for the PCAS (which ranged from 0.74-0.95).

Finally, the PCQ-H queriesconcepts describedby patients and provider/experts throughan extensive interview process. For example,questions about accessibility incorporate items focused on ease of walking in for care and expectations of outreach.Issues related to mental health and addiction issues, which featured prominently in our qualitative interviews, are queried through items designed to elicit concerns that are common in this population (e.g., fear of discrimination) while using language that does not require self-report of actually having a mental or addictive disorder.

Federal and state-level support for credentialing PCMH models within entities such as federally-qualified health centers (including Health Care for the Homeless programs)62 makes this instrument a potential asset to such initiatives. The PCQ-H,at 694 words in length with a 7th grade reading level (Flesch-Kinkaid), is shorter and easier to read than the CAHPS Adult Survey with PCMH items. Internal consistency estimates (α)were higher than or similar to those published for the CAHPS adult core survey24 and the clinician and group visit survey.51In one clinical setting where both PCQ-H and CAHPS have been used for non-research purposes (with roughly 200 patients responding to each), the PCQ-H was described by patients as straightforward, while the CAHPS necessitated frequent questions from patients unsure of how to respond.63

Limitations to the PCQ-H and its development should be acknowledged. First, our reliance on 3 VA samples and a health care program from a state with universal Medicaidlimited our capacity to carefully test item performance in relation to financial accessibility. In order to assure that the resulting instrument would remain applicable in settings with financial barriers, someitems related to financial accessibility were retained. Additionally, while the instrument met study criteria for validity, the stability of response over time remains unclear, pending a formal test-retest assessment.

Acknowledging these limitations, certain unique strengths apply to the instrument development process as well. Most notably, while the PCQ-H was designed to capture domains prioritized in IoM consensus reports, item creation was uniformly preceded by systematic qualitative inquiry with homeless-experienced patients and providers.

We believe the PCQ-H shouldserve as anasset to care providersand payers wishing to assure that organizations funded to care for homeless patients tailor services for this population. Absent an appropriate patient-reported measure, it will remain possible for agencies to secure homeless health care funding without optimizing accessibility (as has been reported12) or other dimensions important to the homeless.One question for future homeless health care design is whether patient ratings of their own care predict better process or outcome measures or more contextually appropriate decisions.64Pending such research, however, a strong case can be made that measuring homeless patients' experiences aligns with a societal interest in fostering medical homes for allpopulations.

Supplementary Material

1. Figure 1: Steps in Instrument Development

2. Table 1: Institute of Medicine Construct Definitions

3. Copy of Primary Care Quality Homeless-33 Survey (English)

4. Primary Care Quality Homeless-33 automatic scoring worksheet

Acknowledgments

Funding: U. S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research & Development Branch Award (IAA 07-069-2)

Footnotes

Disclaimer: Positions and opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not represent views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or any other branch of the U.S. government.

Note: An English-language copy of the Primary Care Quality Homeless-33 is provided as : Supplemental Digital Content to this article, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/MLR/A744 , along with an automatic scoring worksheet in Excel format. : Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/MLR/A745 A Spanish-language certified copy is available on request from the authors.

Contributor Information

Richard N. Jones, Email: rich_jones@brown.edu.

Jocelyn Steward, Email: jocelynsteward@mail.clayton.edu.

Erin J. Stringfellow, Email: estringfellow@go.wustl.edu.

Adam J. Gordon, Email: Adam.gordon@va.gov.

Nancy K. Johnson, Email: nancy.johnson8@va.gov.

Unita Granstaff, Email: unita.granstaff@va.gov.

Erika L. Austin, Email: erika.austin@va.gov.

Alexander S. Young, Email: alexander.young@va.gov.

Joya Golden, Email: joya.golden@va.gov.

Lori L. Davis, Email: lori.davis@va.gov.

David L. Roth, Email: droth@jhu.edu.

References

- 1.Office of Planning and Community Development. The 2013 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress, Part 1: Point-in-Time Estimates of Homelessness. Washington, DC: United States Department of Housing and Urban Development; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burt MR, Aron LY, Lee E, Valente J. Helping America's Homeless: Emergency shelter or affordable housing? Washington, DC: The Urban Institute Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beijer U, Wolf A, Fazel S. Prevalence of tuberculosis, hepatitis C virus, and HIV in homeless people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:859–70. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70177-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hwang SW. Mortality among men using homeless shelters in Toronto, Ontario. JAMA. 2000;283:2152–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.16.2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hwang SW, Orav EJ, O'Connell JJ, Lebow JM, Brennan TA. Causes of death in homeless adults in Boston. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:625–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-8-199704150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hibbs JR, Benner L, Klugman L, et al. Mortality in a cohort of homeless adults in Philadelphia. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:304–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408043310506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buck DS, Brown CA, Mortensen K, Riggs JW, Franzini L. Comparing homeless and domiciled patients' utilization of the harris county, Texas public hospital system. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2012;23:1660–70. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salit SA, Kuhn EM, Hartz AJ, Vu JM, Mosso AL. Hospitalization costs associated with homelessness in New York City. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1734–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199806113382406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gelberg L, Linn LS. Assessing the physical health of homeless adults. JAMA. 1989;262:1973–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kushel MB, Vittingoff E, Haas JS. Factors associated with the health care utilization of homeless persons. JAMA. 2001;285:200–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.2.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baggett TP, O'Connell JJ, Singer DE, Rigotti NA. The unmet health care needs of homeless adults: a national study. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1326–33. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.180109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kertesz SG, McNeil W, Cash JJ, et al. Unmet Need for Medical Care and Safety Net Accessibility among Birmingham's Homeless. J Urban Health. 2014;91:33–45. doi: 10.1007/s11524-013-9801-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wen CK, Hudak PL, Hwang SW. Homeless people's perceptions of welcomeness and unwelcomeness in healthcare encounters. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1011–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0183-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vladeck BC. Health care and the homeless: a political parable for our time. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1990;15:305–17. doi: 10.1215/03616878-15-2-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Toole TP, Bourgault C, Johnson EE, et al. New to care: demands on a health system when homeless veterans are enrolled in a medical home model. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(Suppl 2):S374–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han B, Wells BL. Inappropriate emergency department visits and use of the Health Care for the Homeless Program services by Homeless adults in the northeastern United States. Journal of Public Health Management Practice. 2003;9:530–7. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200311000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, Fried LP, Boult L, Wu AW. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance. JAMA. 2005;294:716–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durso SC. Using clinical guidelines designed for older adults with diabetes mellitus and complex health status. JAMA. 2006;295:1935–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.16.1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiner SJ. Contextualizing medical decisions to individualize care: lessons from the qualitative sciences. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:281–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.True G, Butler AE, Lamparska BG, et al. Open access in the patient-centered medical home: lessons from the Veterans Health Administration. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:539–45. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2279-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerteis M, Edgman-Levitan S, Daley J, Delbanco TL. In: Through the Patient's Eyes: Understanding and Promoting Patient-Centered Care. Paperback, editor. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crofton C, Lubalin JS, Darby C. Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study (CAHPS) Foreword Med Care. 1999;37:MS1–9. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199903001-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Safran DG, Kosinski M, Tarlov AR, et al. The Primary Care Assessment Survey: tests of data quality and measurement performance. Med Care. 1998;36:728–39. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199805000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hargraves JL, Hays RD, Cleary PD. Psychometric properties of the Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study (CAHPS) 2.0 adult core survey. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:1509–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2003.00190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Campbell SM, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A, Marshall MN. Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. BMJ. 2003;326:816–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7393.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. CAHPS Clinician & Group Surveys: 12-Month Survey with Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH) Items. Washington DC: United States Depatment of Health and Human Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gelberg L, Gallagher TC, Andersen RM, Koegel P. Competing priorities as a barrier to medical care among homeless adults in Los Angeles. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:217–20. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.2.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ensign J, Panke A. Barriers and bridges to care: voices of homeless female adolescent youth in Seattle, Washington, USA. J Adv Nurs. 2002;37:166–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merrill JO, Rhodes LA, Deyo RA, Marlatt GA, Bradley KA. Mutual mistrust in the medical care of drug users: the keys to the “narc” cabinet. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:327–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10625.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shortt SE, Hwang S, Stuart H, Bedore M, Zurba N, Darling M. Delivering Primary Care to Homeless Persons: A Policy Analysis Approach to Evaluating the Options. Healthcare Policy. 2008;4:108–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Committee on the Future of Primary Care for the Institute of Medicine. Primary Care: America's Health in a New Era. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America IoM. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi L, Starfield B, Xu J. Validating the adult Primary Care Assessment Tool. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:161. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sofaer S. Qualitative methods: what are they and why use them? Health Serv Res. 1999;34:1101–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steward JL, Holt CL, Pollio DE, et al. Priorities in the Primary Care of Persons Experiencing Homelessness: Convergence and Divergence in the Views of Patients and Provider/Experts. Under Review. 2013 doi: 10.2147/PPA.S75477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Connell JJ, Oppenheimer SC, Judge CM, et al. The Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program: a public health framework. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1400–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.173609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.King N. Doing template analysis. In: Symon G, Cassell C, editors. Qualitative organizational research : core methods and current challenges. Los Angeles ; London: Sage; 2012. pp. 426–50. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Template Analysis - What is Template Analysis. [Accessed June 16, 2013];2004 at http://hhs.hud.ac.uk/w2/research/template_analysis/

- 39.Bradley EH, Curry LA, Devers KJ. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:1758–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd. Thousand Oaks: Sage Inc.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kertesz SG, Holt CL, Steward JL, et al. Comparing homeless persons' care experiences in tailored versus nontailored primary care programs. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(Suppl 2):S331–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Conrad KJ, Yagelka JR, Matters MD, Rich AR, Williams V, Buchanan M. Reliability and validity of a modified Colorado Symptom Index in a national homeless sample. Ment Health Serv Res. 2001;3:141–53. doi: 10.1023/a:1011571531303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roumie CL, Greevy R, Wallston KA, et al. Patient centered primary care is associated with patient hypertension medication adherence. Journal of behavioral medicine. 2011;34:244–53. doi: 10.1007/s10865-010-9304-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boyle GJ. Does item homogeneity indicate internal consistency or item redundancy in psychometric scales? Personality and Individual Differences. 1991;12:291–4. [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeMars C. Item response theory. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. Sixth. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998-2010. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marshall GN, Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. The structure of patient satisfaction with outpatient medical care. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5:477–83. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Samejima F. Graded Response Model. In: Van der Linden W, Hambleton RK, editors. Handbook of Item Response Theory. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH. Psychometric theory. 3rd. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rizopoulos D. ltm: An R Package for Latent Variable Modeling and Item Response Analysis. Journal of Statistical Software. 2006;17 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dyer N, Sorra JS, Smith SA, Cleary PD, Hays RD. Psychometric properties of the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS(R)) Clinician and Group Adult Visit Survey. Med Care. 2012;50(Suppl):S28–34. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31826cbc0d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hays RD, Shaul JA, Williams VS, et al. Psychometric properties of the CAHPS 1.0 survey measures. Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study. Med Care. 1999;37:MS22–31. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199903001-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Revelle W, Zinbarg R. Coefficients Alpha, Beta, Omega, and the glb: Comments on Sijtsma. Psychometrika. 2009;74:145–54. [Google Scholar]

- 54.McDonald RP. Test theory : a unified treatment. Mahwah, N.J: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reise S, Morizot J, Hays R. The role of the bifactor model in resolving dimensionality issues in health outcomes measures. Qual Life Res. doi: 10.1007/s11136-007-9183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ware JE, Jr, Davies-Avery A, Stewart AL. The measurement and meaning of patient satisfaction. Health and Medical Care Services Review. 1978;1(1):3–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hwang SW, Ueng JJ, Chiu S, et al. Universal health insurance and health care access for homeless persons. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1454–61. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.182022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Blue-Howells J, McGuire J, Nakashima J. Co-location of health care services for homeless veterans: a case study of innovation in program implementation. Soc Work Health Care. 2008;47:219–31. doi: 10.1080/00981380801985341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Macnee CL, McCabe S. Satisfaction with care among homeless patients: development and testing of a measure. J Community Health Nurs. 2004;21:167–78. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn2103_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sofaer S, Firminger K. Patient perceptions of the quality of health services. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:513–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.050503.153958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scholle SH, Vuong O, Ding L, et al. Development of and field test results for the CAHPS PCMH Survey. Med Care. 2012;50(Suppl):S2–10. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182610aba. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Health Resources and Services Administration. Program Assistance Letter: HRSA Patient-Centered Medical/Health Home Initiative. Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leon C. Personal Communication to Author of June 25, 2013. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weiner SJ, Schwartz A, Weaver F, et al. Contextual errors and failures in individualizing patient care: a multicenter study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:69–75. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-2-201007200-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

1. Figure 1: Steps in Instrument Development

2. Table 1: Institute of Medicine Construct Definitions

3. Copy of Primary Care Quality Homeless-33 Survey (English)

4. Primary Care Quality Homeless-33 automatic scoring worksheet