Abstract

Aims. CD73 is a membrane associated 5′-ectonucleotidase that has been proposed as prognostic biomarker in various solid tumors. The aim of this study is to evaluate CD73 expression in a cohort of patients with primary bladder cancer in regard to its association with clinicopathological features and disease course. Methods. Tissue samples from 174 patients with a primary urothelial carcinoma were immunohistochemically assessed on a tissue microarray. Associations between CD73 expression and retrospectively obtained clinicopathological data were evaluated by contingency analysis. Survival analysis was performed to investigate the predictive value of CD73 within the subgroup of pTa and pT1 tumors in regard to progression-free survival (PFS). Results. High CD73 expression was found in 46 (26.4%) patients and was significantly associated with lower stage, lower grade, less adjacent carcinoma in situ and with lower Ki-67 proliferation index. High CD73 immunoreactivity in the subgroup of pTa and pT1 tumors (n = 158) was significantly associated with longer PFS (HR: 0.228; p = 0.047) in univariable Cox regression analysis. Conclusion. High CD73 immunoreactivity was associated with favorable clinicopathological features. Furthermore, it predicts better outcome in the subgroup of pTa and pT1 tumors and may thus serve as additional tool for the selection of patients with favorable prognosis.

1. Introduction

Bladder cancer (BC)—the 11th most commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide [1]—presents in up to 80% of all patients either as a noninvasive papillary carcinoma (pTa) or as a carcinoma invading the submucosal connective tissue (pT1) [2, 3]. However, approximately 70% of these superficial tumors recur and up to a quarter even progress into muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) [4]. Since close cystoscopic monitoring of recurrence and progression after initial transurethral resection of the tumor causes immense healthcare costs [5], accurate markers are needed in addition to clinicopathological factors [6] to individualize postoperative follow-up schedules [7–9]. Although numerous studies have evaluated the predictive value of different biomarkers in regard to progression of superficial bladder cancer [10–19], none of them has an established role in daily clinical practice.

CD73 (NT5E, ecto-5′-nucleotidase) is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol- (GPI-) anchored cell-surface enzyme that plays a crucial role in the purinergic signalling pathway by dephosphorylating AMP (adenosine monophosphate) into adenosine [20, 21]. Extracellular adenosine itself is involved in tumor immunoescape and invasion of tumor cells [22], while nonenzymatic functions of CD73 are related to cell adhesion and migration of tumor cells [23, 24].

CD73 expression has been investigated in many different cancer cell lines and human tumor biopsies so far and seems to play an important role in cancer development [20, 25, 26]. The role of CD73 in bladder BC is not well known and controversial [27–30]. Furthermore, neither larger expression studies of CD73 in BC biopsies nor studies investigating the predictive ability of this marker have been published so far. The aim of the present study is to evaluate the association between CD73 expression and tumor progression in a large cohort of patients with primary BC.

2. Material and Methods

Tissue microarrays (TMA) were constructed from 348 formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded urothelial BC tissues from 174 patients as previously described [31]. Tumor samples were represented in duplicate tissue cores with a diameter of 1 mm. The collection of the specimens was performed by the Institute of Surgical Pathology, University Hospital, Zurich, Switzerland, between 1990 and 2006. The tissue samples in TMA represent a series of 174 consecutive (nonselected) primary urothelial bladder tumors consisting of 90 pTa, 68 pT1, and 16 ≥ pT2 tumors. A board-certified pathologist (Peter Wild) reevaluated the hematoxylin-and-eosin-stained slides of all specimens. Tumor stage and grade were assigned according to UICC and WHO criteria. Additionally, to analyse the immunoreactivity of CD73 in normal urothelium, eight slides were cut from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded urothelium of the bladder neck of patients without any history of urothelial dysplasia or BC.

Retrospective clinical follow-up data were available for all the 174 patients (100%). The median follow-up period for the entire cohort was 110.6 months ranging from 32.4 to 226.8 months. Unfortunately, a proper analysis of adjuvant bladder instillation therapy (BCG or chemotherapy) could not be performed due to missing data in about 50% of the patients. The TMA and its clinical cohort have been previously published [32]. Descriptive characteristics of the cohort are depicted in Table 1. The study was approved by the Cantonal Scientific Ethics Committee Zurich (http://www.kek.zh.ch, approval number: StV-NR. 25/2007).

Table 1.

Patient and tumor characteristics and results of immunohistochemical analyses.

| Variable | Categorization | n analyzablea | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 174)a | |||

| Clinicopathologic data | |||

| Age at diagnosis (median, range): 69.5 years (32–92) | <70 years | 87 | 50.0 |

| ≥70 years | 87 | 50.0 | |

| Sex | Female | 43 | 24.7 |

| Male | 131 | 75.3 | |

| Tumor stage (WHO 1973b) | pTa | 90 | 51.7 |

| pT1 | 68 | 39.1 | |

| pT2 | 13 | 7.5 | |

| pT3 | 2 | 1.1 | |

| pT4 | 1 | 0.6 | |

| Histologic grade (WHO 1973b) | G1 | 44 | 25.3 |

| G2 | 87 | 50.0 | |

| G3 | 43 | 24.7 | |

| Histologic grade (WHO 2004c) | Low grade | 101 | 58.0 |

| High grade | 73 | 42.0 | |

| Adjacent carcinoma in situ | No | 158 | 90.8 |

| Yes | 16 | 9.2 | |

| Multiplicity | Solitary | 124 | 71.3 |

| Multifocal | 50 | 28.7 | |

| Growth pattern | Papillary | 159 | 91.4 |

| Solid | 15 | 8.6 | |

|

| |||

| Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | |||

| CD73 | Score 0 | 80 | 46.0 |

| Score 1+ | 48 | 27.6 | |

| Score 2+ | 46 | 26.4 | |

| Ki-67 labelling index | ≤10% | 108 | 62.1 |

| >10% | 66 | 37.9 | |

aAll patients.

bStaging and grading according to the 1973 WHO classification system.

cStaging and grading according to the 2004 WHO classification system.

TMA was freshly cut and used on 3 μm paraffin sections as described previously [33]. The immunohistochemical detection of CD73 on tissue samples was performed by use of Anti-NT5E rabbit polyclonal antibody from Sigma Chemical Company, Saint Louis, United States (dilution 1 : 500). Clone MIB-1 (dilution 1 : 50; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) was used for the detection of Ki-67. Immunohistochemical studies utilised an avidin-biotin peroxidase method with a diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogen. After antigen retrieval (microwave oven for 30 min at 250 W), immunohistochemistry was conducted using a NEXES autostainer (Ventana, Tucson, AZ, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Two experienced pathologists (Lorenz Buser and Peter Wild) evaluated all slides. Membranous CD73 immunoreactivity in the basal layer was assessed by using a semiquantitative three-scale scoring system ranging from 0 to 2+ (score 0: no staining; score 1+: weak staining; score 2+: strong staining).

In the situation of observing different staining intensities between the duplicate tissue cores, the core with more representative tumor tissue was chosen. If both duplicate tissue cores with different staining intensities demonstrate a comparable amount of representative tumor tissue, the intensity of the core with more homogenous staining intensity was selected. Immunoreactivity of CD73 was dichotomized for analytical purposes into a CD73 low-expression group (containing scores 0 and 1+) and a CD73 high-expression group (containing score 2+). The percentage of Ki-67 positive cells of each specimen was determined as described previously [34]. More than 10% of positive tumor cells were defined as a high Ki-67 labelling index [35].

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 22 (IBM, Armonk, USA). p values < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant. The statistical associations between clinicopathological and immunohistochemical data were analysed by using contingency tables together with Fisher's exact test (2-sided) for all binary variables and the Chi-square test (2-sided) for all other nominal variables. In the subgroup of nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC, pTa and pT1), progression-free survival (PFS) was evaluated. Stage-shifts (from pTa to pT1-4 or from pT1 to pT2-4) or the detection of distant metastasis was considered as progression. The Kaplan-Meier method was used for plotting the PFS curves. Significant differences between the curves were analysed by using the two-sided log-rank test. Associations between clinicopathological/immunohistochemical data and PFS were evaluated by univariable and multivariable Cox regression. All significant variables in the univariable analysis were used in the multivariable model.

3. Results

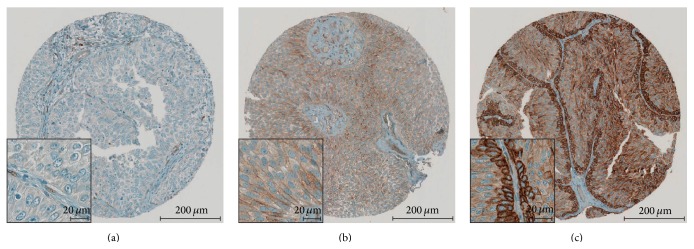

All 174 (100%) tumor samples could be evaluated for CD73 immunoreactivity. CD73 showed a membranous immunoreactivity, which was much more pronounced in the basal layer than in the other tumor cells. Further, a faint and inhomogeneous cytoplasmatic staining was observed in most of the cases with positive membranous staining. In order to allow a distinct evaluation, only membranous CD73 immunoreactivity in the basal layer was assessed. Figure 1 shows representative examples from our TMA for each staining score ranging from 0 to 2+.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical staining pattern of CD73. CD73 shows a distinct membranous immunoreactivity with pronounced intensity in the basal layer. Representative examples of score 0 (a), 1+ (b), and 2+ (c) are depicted.

A strong expression of CD73 (score 2+) was found in 46 of 174 patients (26.4%), whereas in 48 patients (27.6%) a weak immunoreactivity (score 1+) was detected. Finally, 80 patients (46%) showed no CD73 staining. The distribution of the dichotomized staining intensities of CD73 and Ki-67 are shown in Table 1. Additionally, we investigated 8 samples of normal urothelium (Supplementary Figures S1A–F in Supplementary Material available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/785461) of individuals without any history of urothelial dysplasia or carcinoma. We observed a weak and inhomogeneous expression of CD73 in the cytoplasm and cell membrane, which was more pronounced in the basal layer in 4 out of 6 cases (Supplementary Figures S1A–C, F).

Table 2 shows the associations between CD73 staining patterns and clinicopathological parameters (stage, grade, adjacent carcinoma in situ, multiplicity, growth pattern, and Ki-67) of the tumors. High CD73 expression is associated with lower stage (p = 0.006), lower grade (WHO 2004, p = 0.014), less adjacent carcinoma in situ (p = 0.007) and lower Ki-67 expression (p = 0.008). Contingency table analysis for the Ki-67 labelling index and the clinicopathological characteristics have been previously published [32] and showed a significant correlation (p < 0.05) with all clinicopathological characteristics except for tumor multiplicity.

Table 2.

Comparison of the immunohistochemical markers with pathologic characteristics (n = 174).

| Variable | Categorization | CD73 expression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score 0 or 1+ | Score 2+ | p | ||

| Tumor stage (WHO 1973)a | pTa | 57 | 33 | 0.006 |

| pT1 | 57 | 11 | ||

| pT2 | 12 | 1 | ||

| pT3 | 2 | 0 | ||

| pT4 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Histologic grade (WHO 1973)a | G1 | 31 | 13 | 0.100 |

| G2 | 60 | 27 | ||

| G3 | 37 | 6 | ||

| Histologic grade (WHO 2004)b | Low grade | 67 | 34 | 0.014 |

| High grade | 61 | 12 | ||

| Adjacent carcinoma in situb | No | 112 | 46 | 0.007 |

| Yes | 16 | 0 | ||

| Multiplicityb | Solitary | 87 | 37 | 0.130 |

| Multifocal | 41 | 9 | ||

| Growth patternb | Papillary | 115 | 44 | 0.359 |

| Solid | 13 | 2 | ||

|

| ||||

| Immunohistochemistry | ||||

| Ki-67 labelling index | ≤10% | 72 | 36 | 0.008 |

| >10% | 56 | 10 | ||

aChi-square Pearson (2-sided); bold face representing p values <0.05.

bFisher's exact test (2-sided); bold face representing p values <0.05.

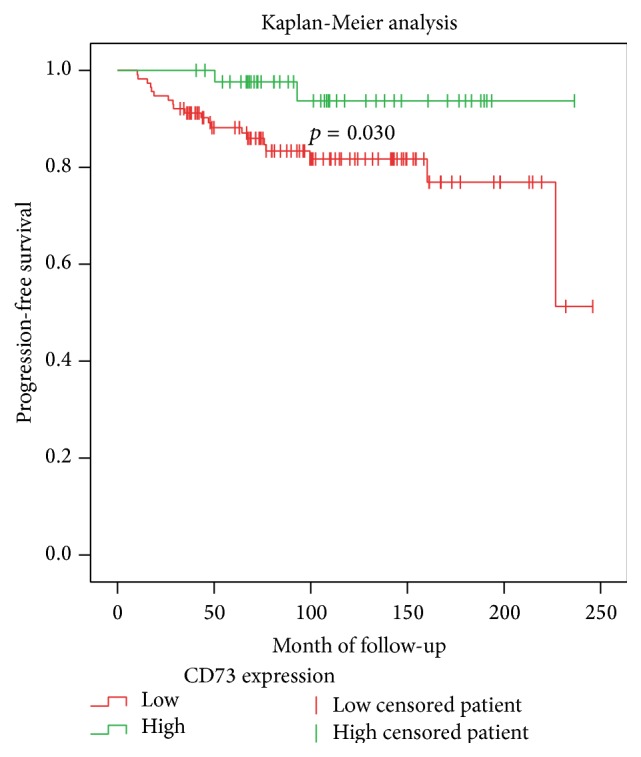

158 out of 174 patients (90.8%) underwent TUR for a primary pTa or pT1 urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. This subgroup was followed for a median of 110.7 months (range: 32.4–245.9 months). In total, 22 patients (13.9%) showed a stage-shift. The median time to progression was 45.2 months ranging from 10.2 to 226.7 months. Kaplan-Meier analysis shows that patients within the subgroup of low CD73 expression have a significantly shorter PFS compared to the subgroup of high CD73 expression (Figure 2). The corresponding log-rank test renders a p value of 0.030. Growth pattern (p < 0.001) and Ki-67 (p = 0.003) were also significantly associated with shorter PFS (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis for progression-free survival comparing high and low CD73 expression. The log-rank test was used for the detection of statistical significance.

Table 3.

Analysis of factors for tumor progression.

| Variable | Categorization | Tumor progression (TP) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n a | Events | p b | ||

| Pathologic data | ||||

| Tumor stage (WHO 1973c) | pTa | 90 | 10 | 0.360 |

| pT1 | 68 | 12 | ||

| Histologic grade (WHO 1973c) | G1 | 44 | 3 | 0.085 |

| G2 | 86 | 12 | ||

| G3 | 28 | 7 | ||

| Histologic grade (WHO 2004d) | Low grade | 99 | 10 | 0.083 |

| High grade | 59 | 12 | ||

| Adjacent carcinoma in situ | No | 146 | 20 | 0.545 |

| Yes | 12 | 2 | ||

| Multifocality | Unifocal tumor | 115 | 15 | 0.465 |

| Multifocal tumor | 43 | 7 | ||

| Growth pattern | Papillary | 151 | 17 | <0.0001 |

| Solid | 7 | 5 | ||

|

| ||||

| Immunohistochemistry | ||||

| CD73 | Score 0 or 1+ | 114 | 20 | 0.030 |

| Score 2+ | 44 | 2 | ||

| Ki-67 labelling index | ≤10% | 106 | 9 | 0.003 |

| >10% | 52 | 13 | ||

aOnly primary pTa and pT1 tumors are included.

bLog-rank test (2-sided); bold face representing p values <0.05.

cStaging and grading according to the 1973 WHO classification system.

dStaging and grading according to the 2004 WHO classification system.

In univariable Cox regression (Table 4), a high expression of CD73 reduces the rate of progression (hazard ratio, HR) by the factor of 0.228 (95% confidence interval [CI] ranging from 0.053 to 0.978; p = 0.047) compared to patients with a low expression of CD73. Of all other clinicopathologic parameters, growth pattern (HR = 7.634 [2.717–21.740]; p < 0.001) and Ki-67 (HR = 3.356 [1.429–7.874]; p = 0.006) were significantly associated with reduced PFS. We performed multivariable Cox regression analysis for all significant predictors in univariable analysis, where CD73 did not remain a significant predictor. Only growth pattern remained an independent predictor for shorter PFS (HR = 3.891 [1.245–12.195]; p = 0.019).

Table 4.

Regression analysis.

| Variable (categorization) | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p value | HR | 95% CI | p value | |||

| Tumor stage (pTa versus pT1) | 1.481 | 0.635 | 3.454 | 0.363 | ||||

| Histologic grade (WHO 2004a) | 2.070 | 0.894 | 4.808 | 0.090 | ||||

| Adjacent carcinoma in situ | 1.563 | 0.363 | 6.711 | 0.549 | ||||

| Multifocality | 1.401 | 0.565 | 3.472 | 0.467 | ||||

| Growth pattern (papillary versus solid) | 7.634 | 2.717 | 21.740 | <0.001 | 3.891 | 1.245 | 12.195 | 0.019 |

| CD73 | 0.228 | 0.053 | 0.978 | 0.047 | 0.319 | 0.072 | 1.408 | 0.132 |

| Ki-67 | 3.356 | 1.429 | 7.874 | 0.006 | 2.222 | 0.873 | 5.650 | 0.094 |

aStaging and grading according to the 2004 WHO classification system.

4. Discussion

This is the first study evaluating CD73 immunoreactivity in a large cohort of primary urothelial bladder carcinomas. We found that high CD73 expression is associated with lower stage, lower grade (WHO 2004), less adjacent carcinoma in situ and lower Ki-67 expression. In the subgroup of NMIBC (pTa and pT1), high CD73 immunoreactivity was associated with longer PFS in univariable Cox regression analysis but did not remain an independent predictor of longer PFS in multivariable Cox regression analysis.

Only a few studies have evaluated the role of CD73 in BC. Similar findings were reported by Wilson et al. who studied neoplastic transformed rodent bladders and detected a loss of CD73 after cancerous transformation [29]. A study using two human bladder cancer cell lines found a CD73 activity in the higher grade cell line of about five times as high as in the lower grade cell line [27]. Rockenbach et al. induced bladder cancer in mice and detected a higher expression of CD73 in the cancerous tissue [30]. One study evaluated CD73 enzyme activity in 36 human bladder cancer biopsies and 9 noncancerous bladder biopsies [28]. CD73 enzyme activity was comparable in BC and in normal urothelial tissue. However, contrary to our work, no follow-up data was reported on BC patients.

Several studies have investigated CD73 immunohistochemistry in other solid tumors. Interestingly, similar results have been reported for gynaecologic neoplasias: Oh et al. investigated 167 epithelial ovarian carcinomas and found associations between overexpression of CD73 and better prognosis, lower stage, and better differentiation [36]. Another study also assigning a favorable prognosis to elevated CD73 expression is the one of Supernat et al. that analysed 136 breast cancers (stages I–III) [37].

However, other investigations of CD73 in different solid tumors found contradictory results: CD73 has been reported as a disadvantageous prognostic or predictive factor, namely, in colorectal, gastric, gallbladder, prostate, and some forms of breast cancer [38–43].

Taken together, conflicting results have been published for the role of CD73 in solid tumors. Interestingly CD73 can be upregulated by several different mediators and conditions such as hypoxia [44, 45] and IFN-beta [46]. Hypoxia is a common characteristic of advanced cancers with poor progression while an increase in IFN-beta activates immunity against tumors [47]. Presence of hypoxia or IFN-beta in these tumors could partially explain the discrepancies. Furthermore, it is important to note that different tissues have very different enzymatic activity of CD73 [48]. This as well can potentially explain differences between different cancers.

In conclusion, our results are in contrast with the current proposed concepts from some authors, where overexpression of CD73 is considered as a disadvantageous factor in carcinogenesis [20, 25, 26]. In our study strong CD73 expression was associated with low-grade tumors, known for their good prognosis. Similar to our work, Oh and Rackley et al. could also detect firstly an inverse relationship between grading and expression of CD73 in epithelial ovarian carcinomas and prostate cancers, respectively, and secondly a direct relationship between expression of CD73 and advantageous prognosis [36, 49]. As in our work, strong CD73 expression was also proposed as a potential marker of good prognosis in breast cancer [37]. Very recently, a molecular biologic link between BC and breast cancer has been found, where a study identified two intrinsic, molecular subsets of high-grade BC, which have similar characteristics of subtypes of breast cancer [50]. The results of this work suggest that molecular characteristics of BC reflect many aspects of breast cancer. Since CD73 promotes the hydrolysis of AMP into adenosine and phosphate [20, 21], the results of our study could also be explained by the proapoptotic effect of adenosine postulated by several articles [51–53].

In our study, high CD73 expression is associated with lower stage and grade and therefore with low risk disease. However, we note that low CD73 expression is also present in a distinct amount of patients with pTa tumors (n = 57, 33%; see Table 2). According to our results presented in Table 2, it seems that strong expression of CD73 has good specificity (0.85) but low sensitivity (0.63) in the prediction of low risk (pTa) tumors.

There are limitations to our study. First, this is a retrospective, single-institution study. Second, information about adjuvant instillation therapy could not be evaluated. As tumor recurrence and progression is known to vary upon instillation therapy, it is an important missing aspect of this study. Also, the investigated study population has been collected over a long time period between 1990 and 2006 where clinical practice with respect to intravesical therapy has changed. Thus, this may have additionally influenced our study results. However, all patients had primary (nonrecurrent) tumors and a long follow-up period, which makes this study population nevertheless meaningful to study. Third, the low rate of MIBC patients has to be mentioned. Hence, no conclusion can be drawn for this group of tumors. Prospective studies with a higher proportion of MIBC are necessary to further evaluate the role of CD73 as a biomarker in BC. Furthermore—beside validation studies for the function of CD73 as a biomarker in BC—more research investigating the role of CD73 as a possible therapeutic target is warranted.

5. Conclusion

High expression of CD73 is observed in BC patients with favorable pathological features. In NMIBC, high CD73 expression was additionally associated with good prognosis. Besides clinical and pathological parameters, detection of strong CD73 expression in BC may help to stratify patients into a low risk group. Further studies are warranted to confirm this hypothesis.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: Normal urothelium (A-F) including von Brunn's nests (E-F) showing a weak and inhomogeneous, partly cytoplasmic and partly membranous immunoreactivity of CD73. The expression of CD73 is slightly accentuated in the basal layer in 4 out of 6 cases (A-C, F).

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Ferlay J., Shin H.-R., Bray F., Forman D., Mathers C., Parkin D. M. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. International Journal of Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epstein J. I., Amin M. B., Reuter V. R., Mostofi F. K. The World Health Organization/International Society of Urological Pathology consensus classification of urothelial (transitional cell) neoplasms of the urinary bladder. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 1998;22(12):1435–1448. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199812000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanchez-Carbayo M., Socci N. D., Lozano J., Saint F., Cordon-Cardo C. Defining molecular profiles of poor outcome in patients with invasive bladder cancer using oligonucleotide microarrays. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(5):778–789. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lapham R. L., Ro J. Y., Staerkel G. A., Ayala A. G. Pathology of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder and its clinical implications. Seminars in Surgical Oncology. 1997;13(5):307–318. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2388(199709/10)13:5<307::aid-ssu4>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Svatek R. S., Hollenbeck B. K., Holmäng S., et al. The economics of bladder cancer: costs and considerations of caring for this disease. European Urology. 2014;66(2):253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sylvester R. J., van der Meijden A. P. M., Oosterlinck W., et al. Predicting recurrence and progression in individual patients with stage Ta T1 bladder cancer using EORTC risk tables: a combined analysis of 2596 patients from seven EORTC trials. European Urology. 2006;49(3):466–477. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Juffs H. G., Moore M. J., Tannock I. F. The role of systemic chemotherapy in the management of muscle-invasive bladder cancer. The Lancet Oncology. 2002;3(12):738–747. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(02)00930-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fradet Y., Lacombe L. Can biological markers predict recurrence and progression of superficial bladder cancer? Current Opinion in Urology. 2000;10(5):441–445. doi: 10.1097/00042307-200009000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee R., Droller M. J. The natural history of bladder cancer: implications for therapy. Urologic Clinics of North America. 2000;27(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(05)70229-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wild P. J., Herr A., Wissmann C., et al. Gene expression profiling of progressive papillary noninvasive carcinomas of the urinary bladder. Clinical Cancer Research. 2005;11(12):4415–4429. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-05-0259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fristrup N., Ulhøi B. P., Birkenkamp-Demtrder K., et al. Cathepsin E, Maspin, Plk1, and survivin are promising prognostic protein markers for progression in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. American Journal of Pathology. 2012;180(5):1824–1834. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarkis A. S., Dalbagni G., Cordon-Cardo C., et al. Nuclear overexpression of p53 protein in transitional cell bladder carcinoma: a marker for disease progression. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1993;85(1):53–59. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cordes I., Kluth M., Zygis D., et al. PTEN deletions are related to disease progression and unfavourable prognosis in early bladder cancer. Histopathology. 2013;63(5):670–677. doi: 10.1111/his.12209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan C.-C., Chang Y.-H., Chen K.-K., Yu H.-J., Sun C.-H., Ho D. M. T. Prognostic significance of the 2004 WHO/ISUP classification for prediction of recurrence, progression, and cancer-specific mortality of non-muscle-invasive urothelial tumors of the urinary bladder: a clinicopathologic study of 1,515 cases. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2010;133(5):788–795. doi: 10.1309/ajcp12mrvvhtckej. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Rhijn B. W. G., Liu L., Vis A. N., et al. Prognostic value of molecular markers, sub-stage and European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer risk scores in primary T1 bladder cancer. BJU International. 2012;110(8):1169–1176. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2012.10996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palou J., Algaba F., Vera I., Rodriguez O., Villavicencio H., Sanchez-Carbayo M. Protein expression patterns of ezrin are predictors of progression in T1G3 bladder tumours treated with nonmaintenance bacillus Calmette-Guérin. European Urology. 2009;56(5):829–836. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Rhijn B. W. G., van Der Kwast T. H., Liu L., et al. The FGFR3 mutation is related to favorable pT1 bladder cancer. Journal of Urology. 2012;187(1):310–314. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Rhijn B. W. G., Zuiverloon T. C. M., Vis A. N., et al. Molecular grade (FGFR3/MIB-1) and EORTC risk scores are predictive in primary non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. European Urology. 2010;58(3):433–441. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alkhateeb S. S., Neill M., Bar-Moshe S., et al. Long-term prognostic value of the combination of EORTC risk group calculator and molecular markers in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer patients treated with intravesical Bacille Calmette-Gurin. Urology Annals. 2011;3(3):119–126. doi: 10.4103/0974-7796.84954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao Z., Dong K., Zhang H. The roles of CD73 in cancer. BioMed Research International. 2014;2014:9. doi: 10.1155/2014/460654.460654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yegutkin G. G. Nucleotide- and nucleoside-converting ectoenzymes: Important modulators of purinergic signalling cascade. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta: Molecular Cell Research. 2008;1783(5):673–694. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghiringhelli F., Bruchard M., Chalmin F., Rébé C. Production of adenosine by ectonucleotidases: a key factor in tumor immunoescape. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology. 2012;2012:9. doi: 10.1155/2012/473712.473712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhi X., Chen S., Zhou P., et al. RNA interference of ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) inhibits human breast cancer cell growth and invasion. Clinical and Experimental Metastasis. 2007;24(6):439–448. doi: 10.1007/s10585-007-9081-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sadej R., Skladanowski A. C. Dual, enzymatic and non-enzymatic, function of ecto-5′-nucleotidase (en, CD73) in migration and invasion of A375 melanoma cells. Acta Biochimica Polonica. 2012;59(4):647–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang B. CD73 promotes tumor growth and metastasis. OncoImmunology. 2012;1(1):67–70. doi: 10.4161/onci.1.1.18068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burnstock G., Di Virgilio F. Purinergic signalling and cancer. Purinergic Signalling. 2013;9(4):491–540. doi: 10.1007/s11302-013-9372-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stella J., Bavaresco L., Braganhol E., et al. Differential ectonucleotidase expression in human bladder cancer cell lines. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations. 2010;28(3):260–267. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Durak I., Perk H., Kavutçu M., Canbolat O., Akyol Ö., Bedük Y. Adenosine deaminase, 5′nucleotidase, xanthine oxidase, superoxide dismutase, and catalase activities in cancerous and noncancerous human bladder tissues. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 1994;16(6):825–831. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90199-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson P. D., Summerhayes I. C., Hodges G. M., Trejdosiewicz L. K., Nathrath W. J. Cytochemical markers of bladder carcinogenesis. The Histochemical Journal. 1981;13(6):989–1007. doi: 10.1007/bf01002639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rockenbach L., Braganhol E., Dietrich F., et al. NTPDase3 and ecto-5′-nucleotidase/CD73 are differentially expressed during mouse bladder cancer progression. Purinergic Signalling. 2014;10:421–430. doi: 10.1007/s11302-014-9405-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kononen J., Bubendorf L., Kallioniemi A., et al. Tissue microarrays for high-throughput molecular profiling of tumor specimens. Nature Medicine. 1998;4(7):844–847. doi: 10.1038/nm0798-844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poyet C., Jentsch B., Hermanns T., et al. Expression of histone deacetylases 1, 2 and 3 in urothelial bladder cancer. BMC Clinical Pathology. 2014;14(1, article 10) doi: 10.1186/1472-6890-14-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fritzsche F. R., Weichert W., Röske A., et al. Class I histone deacetylases 1, 2 and 3 are highly expressed in renal cell cancer. BMC Cancer. 2008;8, article 381 doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nocito A., Bubendorf L., Tinner E. M., et al. Microarrays of bladder cancer tissue are highly representative of proliferation index and histological grade. The Journal of Pathology. 2001;194(3):349–357. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(200107)194:360;349::aid-path88762;3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Rhijn B. W. G., Vis A. N., Van Der Kwast T. H., et al. Molecular grading of urothelial cell carcinoma with fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 and MIB-1 is superior to pathologic grade for the prediction of clinical outcome. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21(10):1912–1921. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oh H. K., Sin J.-I., Choi J., Park S. H., Lee T. S., Choi Y. S. Overexpression of CD73 in epithelial ovarian carcinoma is associated with better prognosis, lower stage, better differentiation and lower regulatory T cell infiltration. Journal of Gynecologic Oncology. 2012;23(4):274–281. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2012.23.4.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Supernat A., Markiewicz A., Welnicka-Jaskiewicz M., et al. CD73 expression as a potential marker of good prognosis in breast carcinoma. Applied Immunohistochemistry & Molecular Morphology. 2012;20(2):103–107. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e3182311d82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu N., Fang X.-D., Vadis Q. CD73 as a novel prognostic biomarker for human colorectal cancer. Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2012;106(7):918–919. doi: 10.1002/jso.23159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu X.-R., He X.-S., Chen Y.-F., et al. High expression of CD73 as a poor prognostic biomarker in human colorectal cancer. Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2012;106(2):130–137. doi: 10.1002/jso.23056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu X.-X., Chen Y.-T., Feng B., Mao X.-B., Yu B., Chu X.-Y. Expression and clinical significance of CD73 and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α in gastric carcinoma. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013;19(12):1912–1918. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i12.1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xiong L., Wen Y., Miao X., Yang Z. NT5E and FcGBP as key regulators of TGF-1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) are associated with tumor progression and survival of patients with gallbladder cancer. Cell and Tissue Research. 2014;355(2):365–374. doi: 10.1007/s00441-013-1752-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang Q., Du J., Zu L. Overexpression of CD73 in prostate cancer is associated with lymph node metastasis. Pathology and Oncology Research. 2013;19(4):811–814. doi: 10.1007/s12253-013-9648-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Loi S., Pommey S., Haibe-Kains B., et al. CD73 promotes anthracycline resistance and poor prognosis in triple negative breast cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(27):11091–11096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222251110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thompson L. F., Eltzschig H. K., Ibla J. C., et al. Crucial role for ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) in vascular leakage during hypoxia. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2004;200(11):1395–1405. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Synnestvedt K., Furuta G. T., Comerford K. M., et al. Ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) regulation by hypoxia-inducible factor-1 mediates permeability changes in intestinal epithelia. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2002;110(7):993–1002. doi: 10.1172/jci200215337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kiss J., Yegutkin G. G., Koskinen K., Savunen T., Jalkanen S., Salmi M. IFN-β protects from vascular leakage via up-regulation of CD73. European Journal of Immunology. 2007;37(12):3334–3338. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vaupel P. The role of hypoxia-induced factors in tumor progression. Oncologist. 2004;9(supplement 5):10–17. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.9-90005-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Colgan S. P., Eltzschig H. K., Eckle T., Thompson L. F. Physiological roles for ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) Purinergic Signalling. 2006;2(2):351–360. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-5302-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rackley R. R., Lewis T. J., Preston E. M., et al. 5′-nucleotidase activity in prostatic carcinoma and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Cancer Research. 1989;49(13):3702–3707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Damrauer J. S., Hoadley K. A., Chism D. D., et al. Intrinsic subtypes of high-grade bladder cancer reflect the hallmarks of breast cancer biology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(8):3110–3115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318376111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kulkarni J. S., Przywara D. A., Wakade T. D., Wakade A. R. Adenosine induces apoptosis by inhibiting mRNA and protein synthesis in chick embryonic sympathetic neurons. Neuroscience Letters. 1998;248(3):187–190. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(98)00369-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saitoh M., Nagai K., Nakagawa K., Yamamura T., Yamamoto S., Nishizaki T. Adenosine induces apoptosis in the human gastric cancer cells via an intrinsic pathway relevant to activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2004;67(10):2005–2011. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.El-Darahali A., Fawcett H., Mader J. S., Conrad D. M., Hoskin D. W. Adenosine-induced apoptosis in EL-4 thymoma cells is caspase-independent and mediated through a non-classical adenosine receptor. Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 2005;79(3):249–258. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1: Normal urothelium (A-F) including von Brunn's nests (E-F) showing a weak and inhomogeneous, partly cytoplasmic and partly membranous immunoreactivity of CD73. The expression of CD73 is slightly accentuated in the basal layer in 4 out of 6 cases (A-C, F).