Abstract

The World Health Organization Suicide trends in at-risk territories study is a multi-site regional research program operating first in French Polynesia and countries of the Western Pacific, then extended to the world. The aims of the study were to establish a monitoring system for suicidal behaviors and to conduct a randomised control trial intervention for non-fatal suicidal behaviors. The latter part is the purpose of the present article. Over the period 2008-2010, 515 patients were admitted at the Emergency Department of the Centre Hospitalier de Polynésie Française for suicidal behavior. Those then hospitalized in the Psychiatry Emergency Unit were asked to be involved in the study and randomly allocated to either Treatment As Usual (TAU) or TAU plus Brief Intervention and Contact (BIC), which provides a psycho-education session and a follow-up of 9 phone contacts over an 18-months period. One hundred persons were assigned to TAU, while 100 participants were allocated to the BIC group. At the end of the follow-up there were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of number of presentations to the hospital for repeated suicidal behaviors. Although the study could not demonstrate the superiority of a treatment over the other, nevertheless – given its importance – the investigation captured public attention and was able to contribute to the awareness of the need of suicide prevention in French Polynesia. The BIC model of intervention seemed to particularly suit the geographical and health care context of the country.

Key words: Tahiti, suicide, prevention, randomized trial

Introduction

The Western Pacific region contains a diverse range of countries that differ in terms of culture, population size, and health care facilities.1 Pacific island communities, even those that remain territories of European nations, such as French Polynesia, do not reach the same standards of psychiatric care as available in urban western centers.2

French Polynesia includes over 113 islands, scattered over an area larger than Europe. Out of the 268,270 inhabitants counted in the 2012 census of French Polynesia,3 only the 178,174 inhabitants of Tahiti (the main island) have access to psychiatric and psychological care (e.g. Centre Hospitalier de Polynésie Française). The geographical remoteness of the other 112 islands of the country makes treatment of mental conditions difficult. Suicide standardized rates remarkably increased in recent years:4 from 9.7 per 100,000 in the 1999-2004 period to 11.3 per 100,000 in 2005-2010, with a peak in 2008 of 13.7 per 100,000. Increased suicide rates have elicited a number of suicide prevention activities moduled around the geographical and socio-cultural context of the country.5 With regards to non-fatal suicidal behavior, one of the strategies suggested to mitigate the risk of recurrance is reinforcement of social support by maintaining long-term contact with suicidal individuals. A number of studies tested this approach producing mixed results (Table 1). Several studies suggest that regular contact with patients may help to reduce both deaths due to suicide and repetition of suicide attempts.6-17 Other investigations fail to show any effects on either deaths due to suicide,15 or suicide attempt repetitions.19,20 It has been hypothesized that strategies improving social connectedness might be particularly pertinent in the context of isolated Pacific islands.21

Table 1.

Studies on continuity of care of suicide attempters or individuals at-risk of suicidal behavior.

| Country | Intervention in population having committed a suicide attempt | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Australia12 | 12 contacts (postal cards every month) after hospital discharge. Young aged 15-24 | RCT, n=778. SA ns; SA in intervention group 57/378, 15.1% (95%CI 11.5% to 18.7%) vs in control group 68/394, 17.3% (13.5% to 21.0%). However, in unadjusted analysis the number of repetitions was significantly reduced [IRR=0.55 (0.35 to 0.87)] |

| Taiwan16 | 6-12 contacts (phone calls during 3-6 month, 2/month). Frequency of contacts change following assessment of risk (BSRS, Pierce RS, SAD PERSONS S): high (psychiatrist), moderate (1-2 contacts/week), low (2 contacts/month), no risk (stop contacts) | No RCT, n= 44,364 received aftercare (854 died by suicide) S*. Interventions decreased subsequent suicides for attempters (with initial willingness for aftercare OR=0.36, 95%CI 0.26-0.51; without initial willingness for aftercare: OR=0.78, 95%CI 0.62-0.97). In addition, aftercare was shown to prolong duration to eventual death. |

| Spain14 | 7 contacts (phone call at 1 week, 1, 3, 6, 9, 12 months) to assess risk and increase adherence to treatment | RCT, n=991. SA*, Delayed SA*. Mean time in days to first reattempt=346.47 for intervention vs 316.46 in the control group. |

| Iran15 | 8-9 contacts (postal cards, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 months + birthday) to assess risk and increase adherence to treatment | RCT, n=2300. SA*, SI*. Reeducation of SI (relative risk reduction (RRR)=0.31, 95%CI 0.22-0.38), SA (RRR=0.42, 95%CI 0.11-0.63) in the intervention group compared to control group. |

| New Zealand11 | 6 contacts (postal cards over 12 months) after hospital discharge | RCT, n=327. SA ns. No significant differences between the control and intervention groups in the proportion of participants re-presenting with self-harm or in the total number of re-presentations for self-harm. |

| Brazil, India, Sri Lanka, Iran, China8,19 | 1 hour education session (epidemiology, risk and protecting factors, help solutions, human and phone resources) + 9 contacts (phone call or visit at 1, 2, 4, 7, 11 weeks/4, 6, 12, 18 months) | RCT, n=1867. S* SA ns. Significant reeducation of suicides in the intervention group (BIC, 0.2% vs TAU, 2.2%, chi2=13.83, P<0.001). No change in SA - similar in the BIC and TAU groups (7.6% vs. 7.5%, chi2=0.013; P=0.909), but differences in rates across the five sites. |

| France17 | 3 contacts (phone call at 1, 3, 13 months) after hospital discharge | RCT, n= 605. 1 mo. SA* 3 mo. SA ns. The number of participants contacted at one month who reattempted suicide was significantly lower than that of controls [12% (13/107) vs 22% (62/280); chi2=4.7, df=1, P=0.03]. No differences in the follow-up at 3 months. |

| Australia13 | 8 contacts (postal cards at 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 months) after hospital discharge | RCT, n=772. SA*. Significant reduction in the rate of SA repetition, with incidence risk ratio of 0.49 (95%CI 0.33-0.73) |

| Sweden18 | 2 contacts (phone calls at 1, 5 months after 1st SA) + support to initiate or go on the treatment | RCT, n=216. SA ns. Randomized groups did not differ in repetition of SA during follow-up or in improvement in GSI (SCL-90), GAF and SSI, but individuals with no initial treatment the intervention group improved more in certain psychological symptom dimensions (SCL-90). |

| Italy6,7 | 2 contacts / week for assessment of the needs and to provide emotional support in the elderly + Alarm system to call for help (tele-help/tele-check service) | No RCT. S*. Short-term: Only one death by suicide in the elderly subjects connected to Tele-Help/Tele-Check vs expected number of 7.44 for the general population. Long-term: Significantly fewer suicide deaths (n=6) occurred among elderly service users [standardized mortality ratio (SMR) 28.8%] than expected (n=20.86; chi2=10.58, d.f.=1, P<0.001) |

| USA9,10 | 4 contacts (letters during 5 years) after hospital discharge and refusal to be treated. Follow-up up to 15 years after SA | RCT, n=843. S*. Short term (3 years) and long term (5 and 15 years): Intervention group shows the lowest rate of suicide (P=0.04) in the first five years. Then, the difference with the control group diminishes and disappears after 14 years. |

*Significant reduction; ns, non-significant; SA, suicide attempt; SI, suicidal ideation; S, Suicide; RCT: Randomised Control Trial.

The WHO Suicide Trends in At-Risk Territories (START) study was launched in 2007 in the Western Pacific Region of WHO. There are four components in the START study: component i) a monitoring system to collect systematic informations about fatal and non fatal suicidal behaviors, ii) a randomized control trial intervention for non-fatal suicidal behaviors, iii) a psychological autopsies, and iv) a follow-up of medically serious suicide attempters. While its main features have been described elsewhere,22 This paper presents the results of the Component Two, a randomised control intervention performed on suicidal individuals of French Polynesia, comparing treatment as usual (TAU) with treatment as usual plus Brief Intervention and Contact (BIC).

Materials and Methods

Study protocol

The Component Two of the START study applied the same protocol as the WHO/Suicide Prevention-Multisite Intervention Study on Suicide (SUPRE-MISS).8 The WHO/SUPRE-MISS study presented a significant reduction in both general mortality and death by suicide in the group treated with TAU + BIC at the 18-month follow-up in several middle- and low-income countries.8

Outcome measures

This randomized controlled trial used number of suicides and repeated non-fatal suicidal behavior (NFSB), as primary outcome measures.

Implementation of the study

In French Polynesia, the START research team was composed of one psychiatrist (SA), three psychologists (MR, AM, PF), one epidemiologist (NLN), and a few psychology students. The relevant ethics committee approved the research protocol (Comité d’Ethique de Polynésie Française, notice n° 29 of the 11.01.2007) and a grant from the Etablissement Public Administratif pour la Prévention (Minsitry of Health) permitted the implementation of the study, which operated from 1st January 2008 to 30 June 2012. All patients gave written consent to enrol in the randomized controlled trial. The initial interviews were conducted face-to-face by a trained psychiatrist or psychologist a maximum of 3 days after admission to the Psychiatric Department. Psychologists and psychiatrists also conducted the follow-up contacts.

Enrollment and sample size

Over the period 2008-2010, 556 presentations of NFSB by 515 persons were admitted to the Emergency Department of the Centre Hospitalier de Polynésie Française (CHPF). This involves all behaviors of intentional self-harm, regardless of the presence of suicidal intention.23

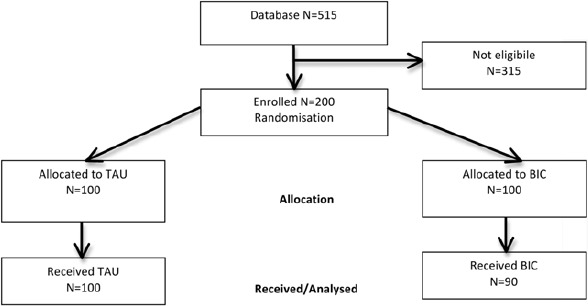

Due to limited fund availability, investigators decided to lock the maximum entry to the study at 200 subjects. A sequence based on a random procedure (block randomization) was used to assign all enrolled subjects to TAU (n=100) or TAU + BIC (n=100) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of suicide trends in at-risk territories study in French Polynesia.

In French Polynesia, TAU consists of one psychiatric assessment for all suicide attempters, and then either hospitalisation, outpatient follow-up, or no care at all. All patients included in this study had a short psychiatric hospitalization (minimum 24 hours), with some of them receiving outpatient psychiatric or psychological follow-up. In addition to TAU, the BIC treatment modality included: i) a one-hour information session, as close to the time of discharge as possible; ii) nine follow-up contacts (phone calls according to a specific agenda at 1, 2, 4, 7 and 11 week(s), and 4, 6, 12 and 18 months) after the intake, which were conducted by a person with clinical experience (e.g. psychiatrist or psychologist). During these contacts, questions included whether the patients had repeated the suicidal behavior, how they felt, whether they needed help and if they had sought support. Subjects receiving only TAU were contacted using the START follow-up form - as for the TAU+BIC group - at 12 and 18 months after discharge from hospital.

Instruments

The survey questionnaire used in Component Two of the WHO/START Study was translated into French and Tahitian, and adapted to take into account cultural specificities, then back-translated to English and pilot-tested in 20 participants recruited from the Emergency Department of the Centre Hospitalier de Polynésie Française. The questionnaire was largely based on the European Parasuicide Study Interview Schedule (EPSIS),24 which had been used in the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study on Suicidal Behavior.25 It covered socio-demographic and clinical information (e.g. mental and physical health status, traumatic experiences, alcohol and drug use), and included several self-report scales (for a detailed description, see De Leo et al.).22 An one-page questionnaire was used to record follow-up contacts with the patients., Additional information from the hospital emergency department was obtained because participants may fail to report new episodes of non-fatal suicidal behavior. Coroner’s records of deaths by suicide one year after the end of study were also reviewed.

Data analysis

Data entry and cleaning were conducted under the direction of the principal investigator (S.A.), with the help of two clinical psychologists (M.R., A.M.) and double-checked by an epidemiologist (L.N.). Selected variables (age, sex, marital status, education employment, consequences of the act, psychiatric disorders) were compared to determine any differences between the two treatment groups by using the chi-square test. The Fisher’s exact test was used with small numbers per group (less than 5). A probability level of 0.05 (two-sided) was considered as significant.

Results

Figure 1 depicts the enrolment of subjects. These were more frequently female, single, with secondary education and employed (Table 2). Over half of subjects in the TAU+BIC group had a diagnosis of mood disorder. A large proportion of cases (63% in the TAU+BIC, 72% in TAU only group) had previous history of suicidal behaviors before the index episode.

Table 2.

Socio-demographic characteristics of subjects enrolled (n=190).

| Characteristics | TAU (n=100) | BIC (n=90) | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Age (years) | - | 31.48 | - | 33.00 | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 36 | 36 | 31 | 34.4 | 0.8 | |

| Female | 64 | 64 | 58 | 64.4 | 0.9 | |

| Transsexual | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.1 | 0.5 | |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 32 | 32 | 25 | 27.8 | 0.5 | |

| Married | 53 | 53 | 58 | 64.4 | 0.1 | |

| Widowed | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.1 | 1.0 | |

| Divorced | 12 | 12 | 5 | 5.6 | 0.1 | |

| Education | ||||||

| None | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1.1 | 0.4 | |

| Primary | 6 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 0.3 | |

| Secondary | 57 | 57 | 38 | 42.2 | 0.04 | |

| Higher (non-university) | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 1.0 | |

| University | 14 | 14 | 25 | 27.8 | 0.01 | |

| Other | 10 | 10 | 8 | 8.9 | 0.8 | |

| Employment | ||||||

| Full/part-time | 50 | 50 | 44 | 49.4 | 0.9 | |

| Temporary | 6 | 6 | 9 | 10.1 | 0.3 | |

| Unemployed | 14 | 14 | 18 | 20.2 | 0.3 | |

| Disabled | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1.0 | |

| Retired | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1.1 | 0.4 | |

| Student | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 1.0 | |

| Armed services | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | |

| Housekeeper | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4.5 | 0.6 | |

| Other | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 0.9 | |

| Consequences | ||||||

| None | 32 | 32.3 | 23 | 25.6 | 0.3 | |

| No danger to life | 41 | 41.4 | 46 | 51.1 | 0.2 | |

| Danger to life | 17 | 17.2 | 19 | 21.1 | 0.5 | |

| No information | 9 | 9.1 | 2 | 2.2 | 0.04 | |

| Psychiatric disorder | ||||||

| Alcohol use disorder | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3.3 | 0.7 | |

| Cannabis use disorder | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.1 | 1.0 | |

| Psychotic disorder | 7 | 7 | 3 | 3.3 | 0.3 | |

| Mood disorder | 50 | 50 | 47 | 51.7 | 0.8 | |

| Anxiety/adjustment disorder | 17 | 17 | 16 | 17.6 | 0.9 | |

| Personality disorder | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2.2 | 1.0 | |

TAU, Treatment As Usual; BIC, Brief Intervention and Contact.

There was no statistical difference in the frequency of suicidal behavior (suicides and repeated NFSB) between TAU+BIC and TAU only groups (Table 3). Incidentally, two cases of suicide were recorded in the TAU only group versus none in those that received TAU+BIC.

Table 3.

Results of Brief Intervention and Contact after 18 months follow-up in French Polynesia (n=190).

| Characteristics | TAU (n=100) | BIC (n=90) | Test | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| New episodes of non-fatal Suicidal behavior | 21 | 21.0 | 24 | 26.7 | Chi² = 0.84 | 0.360 |

| Suicide | 2 | 2.0 | 0 | 0 | Fisher’s exact | 0.500 |

Additional analysis in specific subgroups at higher risk of suicidal behavior was performed (Table 4). Following subgroups were chosen: i) those with personality disorders, ii) those with a history of sexual abuse, and iii) those who had made multiple (n≥3) attempts before participating in the study. BIC+TAU did not show significant differences compared to TAU in specif subgroups (Table 4). However, it is important to note that subgroups are small with limited statistical power.

Table 4.

Suicide repeated NFSB in different subgroups of Brief Intervention and Contact after 18 months follow-up in French Polynesia.

| TAU | BIC | Test | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N* | % | n/N* | % | |||

| Personality disorders (primary and secondary dg) | 3/12 | 25.0 | 5/11 | 45.5 | Fisher exact | 0.400 |

| History of sexual abuse | 9/21 | 42.8 | 5/15 | 33.3 | Chi2=0.33 | 0.563 |

| Past history of suicide attempt | >37/14 | 50.0 | 9/17 | 52.9 | Chi2=0.03 | 0.870 |

TAU, Treatment As Usual; BIC, Brief Intervention and Contact.

*N, persons with the condition; n, persons with the condition repeatsing NFSB during follow-up.

Discussion

This study was part of a multisite, cross-cultural research study that sought to evaluate the effectiveness of a simple follow-up model of care (BIC) in persons who sought help from an Emergency Department due to non-fatal suicidal behavior. As a clinical note, in most cases patients were happy to be involved in the study and to receive the follow-up phone calls, especially the residents of remote islands. Females were more compliant than males to follow-up contacts attempt.

This study was initially designed as a multi-site intervention in Pacific region, however, only French Polynesia could implement it in the hospital setting. Therefore the size of the sample and the timeframe of the investigation (eighteen months for each case) made it difficult to obtain a statistically detectable impact in terms of suicide deaths. However, a difference in relapse to non-fatal suicidal behavior might be found. We are not aware of similar studies from the Pacific area, but it is possible that, with a mean follow up of 1.5 years, a 1-2% reduction of deaths by suicide could be expected within that timeframe, on the basis of comparable studies (see, for example Hwton et al.).26 In this experience, two suicides did occur in the TAU sample only, with none in the TAU+BIC. Since statistical significance was not found, these differences cannot be attributable to intervention. As in the case of the WHO/SUPRE-MISS study,20 also this experience in French Polynesia did not show differences in terms of repeated NFSB frequency between the two groups of subjects. We may speculate that the observed differences are too small to permit differentiation, or that heterogeneity within the NFSB performers obscured any measurable effect. These individuals comprise subjects of different ages, with or without psychiatric diagnosis and/or history of multiple attempts/self-harm episodes, with a history of alcohol or drug misuse, and with different levels of suicide intention (from zero to full determination). These particularities may be equally distributed within the two groups of subjects (TAU and TAU+BIC), but in reality the final figures would absorb the significant variability in group composition andmay dilute treatment impacts. However, the (very) small numbers of subgroups (Table 2) do not show differences, and no particular subgroup seemed to significantly benefit from the brief intervention and contact. Another possible explanation lies on the rather intense level of care that every suicidal subject routinely receives in French Polynesia. Close to 100% of suicidal subjects do receive psychiatric assessment, and on average about 50% are hospitalised (usually between 1 day and 1 week) for the treatment of suicidal crisis. Of these, about 65% would also receive psychiatric or psychological follow up. This indicates that most of TAU subjects in French Polynesia actually receive considerable clinical support following NFSB. It is possible that this significant effect of the current TAU model obscures any potentially gain by the addition of BIC. We could make the assumption that TAU+BIC would be significantly more effective than TAU alone if TAU would not include such substantial psychiatric intervention and treatment, as is the case of many countries participating to the START Study.27 Consequently, in countries where psychiatric treatment is routinely available, BIC perhaps may be improved by focus on integration with the primary treatment providers or by increased frequency or structure of contacts to offer a detectable risk reduction. It is also possible that BIC might encourage increased relapse of non-fatal suicidal behavior in subjects driven to attract more attention from care providers and proxies.19

Apart from sample size, the study acknowledges several other limitations, particularly the relevant drop-out rate in both TAU+BIC and TAU only groups. We could detect that the main reason for absence of contact was the expiration of mobile phone cards. This is problematic, because it could lead to an underestimation of new episodes of NFSB or deaths. As mentioned above, we tried to limit this bias by improving the collection of information from other sources and the information about the main outcome measures from hospital database and coroner’s office using intention to treat approach. Checks were made from the hospital database of admissions, and police files in case of violent deaths. Further, the sample is potentially affected by selection issues as the geographical distribution of the country made it difficult to connect with those in communities outside the main island of Tahiti. These physical barriers may prevent some people from seeking treatment following a suicide attempt even when they were invited to do so. Considering this, a telephone management programme for patients discharged from the ED after an episode of suicidal behavior could markedly improve the maintenance of contact and maybe helpful in reducing the recurrence of these dangerous behaviors in the remote islands of French Polynesia.

Conclusions

Further research is needed in order to assess whether the addition to treatment as usual of BIC intervention is helpful or not in suicidal patients. In French Polynesia, suicidal behaviors are often linked to difficult relationships or separations in couples, often complicated by impulsive acts, such as suicide or self harm. Education and awareness in the community about suicide and its possible precipitating factors may be one way of addressing this problem.28 However, this type of population-level approach to suicide prevention is likely to be a long-term and resource-intensive effort, difficult to implement and (especially) sustain in Pacific islands. Therefore, we believe that – for the time being - it could be more profitable to focus on targeted populations, such as those with history of suicidal behavior.29 In addition, the BIC program could be improved and designed in a more culturally appropriate way. The majority of participants was satisfied with the long-term support provided by telephone contacts and that no suicide cases were registered in the BIC groupit seems justified to continue research efforts on this type of program. A way to improve contact could be constituted by the use of a combination of different strategies, including the use of crisis cards for first attempters, phone calls and post cards or the availability of a crisis line managed by volunteers or professionals.30-33 Taken together with the START experience in French Polynesia, this kind of multiple-intervention approach could integrate the complementary/alternative care or the culturally-accepted supports (like religious communities) or traditional relaxing contact (like aromatherapy taurumi monoi psychophysical care) associated with psychiatric/psychological care. The START study approach, with its attention on cultural differences,27 could contribute better to the effectiveness of these low-cost strategies in locations where services for mental conditions and emotional distress are scarce.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Yves Petit (Psychiatric Department), Dr Fabrice Jeanette (Emergency Department), Dr Nathalie Lecordier, Patricia Page, Kamel Boussouak), Guillaume Garcia, for the clinical assistance provided.

Funding Statement

Funding: tthe study was funded by the French Polynesia Ministry of Health and the Centre Hospitalier de Polynésie Française.

References

- 1.WHO Western Pacific Region. Country health information profiles: statistical tables. Manila: WPRO; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Mental health atlas. 2011. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9799241564359_eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institut de la Statistique de Polynésie française. Available from: www.ispf.pf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yen Kai Sun L. Epidemiological characteristics of suicide deaths in French Polynesia (2005-2010). Abstract book of the 6th Asia Pacific IASP conference on suicide prevention, Tahiti, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Leo D, Milner A, Xiangdong W. Suicidal behavior in the western pacific region: characteristics and trends. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2009;39:72-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Leo D, Carollo G, Dello Buono M. Lower suicide rates associated with a tele-help/tele-check service for the elderly at home. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:632-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Leo D, Dello Buono M, Dwyer J. Suicide among the elderly: the long-term impact of a telephone support and assessment intervention in northern Italy. Br J Psychiatry 2002;181:226-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fleischmann A, Bertolote JM, Wasserman D, et al. Effectiveness of brief intervention and contact for suicide attempters: a randomized controlled trial in five countries. Bull World Health Organ 2008;86:703-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Motto JA. Suicide prevention for high-risk persons who refuse treatment. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1976;6:223-30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Motto JA, Bostrom AG. A randomized controlled trial of postcrisis suicide prevention. Psychiatr Serv 2001;52:828-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beautrais AL, Gibb SJ, Faulkner A, et al. Postcards intervention for repeat self-harm: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2010;197:55-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter GL, Glover K, Whyte IM, et al. Postcards from the edge project: randomised controlled trial of an intervention using postcards to reduce repetition of hospital treated deliberate self-poisoning. Br Med J 2005;331:805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carter GL, Glover K, Whyte IM, et al. Postcards from the edge project: 24 months outcomes of a randomised controlled trial for hospital treated self-poisoning. Br J Psychiatry 2007;191:548-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cebrià AI, Parra I, Pàmias M, et al. Effectiveness of a telephone management programme for patients discharged from an emergency department after a suicide attempt: controlled study in a spanish population. J Affective Disorders 2013; 147:269-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hassanian-Morghaddam H, Sarjami S, Kolahi AA, Carter GL. Postcards in persia: randomised controlled trial to reduce suicidal behaviors 12 months after hospital-treated self-poisoning. Br J Psychiatry 2011;198:309-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan YJ, Chang WH, Lee MB, et al. Effectiveness of a nationwide aftercare program for suicide attempters. Psychol Med 2013;43:1447-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaiva G, Ducrocq F, Meyer P, et al. Effect of telephone contact on further suicide attempts in patients discharged from an emergency department: randomised controlled study. Br Med J 2006;332:1241-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cedereke M, Monti K, Fonagy P. Telephone contact with patients in the year after a suicide attempt: does it affect treatment attendance and outcome? A randomised controlled study. Eur Psychiatry 2002;17:82-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bertolote JM, Fleischmann A, De Leo D, et al. Repetition of suicide attempts: data from emergency care setting in five culturally different low-and middle- income countries participating in the WHO SUPRE-MISS study. Crisis 2010;31:194-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson J, Yuen HP, Gook S, et al. Can receipt of a regular postcard reduce suicide-related behavior in young help seekers? A randomized controlled trial. Early Interv Psychiatry 2012;6:145-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Millner A, McClure R, De Leo D. Globalization and suicide. An ecological study across five regions of the world. Arch Suicide Res 2012;16:238-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Leo D, Milner A. The Start Study: promoting suicide prevention for a diverse range of cultural contexts. Suicide Life Threat Behav 2010;40:99-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Leo D, Burgis S, Bertolote JM, et al. Definitions of suicidal behavior. Lessons learned from the WHO/EURO multicentre study on suicidal behavior. Crisis 2006;27:4-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kerkhof A, Bernasco W, Bille-Brahe U, et al. European parasuicide study interview schedule (EPSIS). Bille-Brahe U, ed. Facts and figures: WHO/EURO, 1999. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmidtke A, Bille-Brahe U, De Leo D, et al. Attempted suicide in Europe: rates, trends and sociodemographic characteristics of suicide attempters during the period 1989-1992. Results of the WHO/EURO multicentre study on parasuicide. Acta Psyhiatr Scand 1996;93:327-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawton K, Bergen H, Waters K. Epidemiology and nature of self-harm in children and adolescents: findings from the multicentre study of self-harm in england. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012;21:369-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Leo D, Milner A, Fleischmann A, et al. The WHO START study suicidal behaviors across different areas of the world. Crisis 2013;34:156-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Gioannis A, De Leo D. Managing suicidal patients in clinical practice. Open J Psychiatry 2012;2:49-60. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vijayakumar L, Shujaath Ali ZS, Deravaj P, Kesavan K. Intervention for suicide attempters: a randomized controlled study. Indian J Psychiatry 2011;53:244-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vaiva G, Walter M, Arab A, et al. Algos: the development of a randomized controlled trial testing a cases management algorithm designed to reduce suicide risk among suicide attempters. BMC Psychiatry 2011;11:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luxton DD, June JD, Comptois KA. Can postdischarge follow-up contacts prevent suicide and suicidal behavior? A review of the evidence. Crisis 2013;34:32-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coveney CM, Pollock K, Armstrong S, Moore J. Caller’s experiences of contacting a nationale suicide prevention helpline. Crisis 2012;33:313-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pham-Scottez A. Evaluation de l’efficacité d’une permanence téléphonique sur l’incidence des tentatives de suicide des patients borderline. Annales Médico-Psychologiques 2010;168:141-4. [Google Scholar]