Abstract

A facile method to synthesize a TiO2/PEDOT:PSS hybrid nanocomposite material in aqueous solution through direct current (DC) plasma processing at atmospheric pressure and room temperature has been demonstrated. The dispersion of the TiO2 nanoparticles is enhanced and TiO2/polymer hybrid nanoparticles with a distinct core shell structure have been obtained. Increased electrical conductivity was observed for the plasma treated TiO2/PEDOT:PSS nanocomposite. The improvement in nanocomposite properties is due to the enhanced dispersion and stability in liquid polymer of microplasma treated TiO2 nanoparticles. Both plasma induced surface charge and nanoparticle surface termination with specific plasma chemical species are proposed to provide an enhanced barrier to nanoparticle agglomeration and promote nanoparticle-polymer binding.

The formation of nanocomposites, through nanoparticle (NP)—liquid polymer routes, and nanofluids, through establishing stable suspensions of NPs in liquid, offers considerable opportunities to design new materials and functionalities for a wide range of applications. Taylor et al.1 provided a detailed review of nanofluids as heat/mass transport materials, phase-change materials, electromagnetically active media, catalysts, and their application in medicine for cancer treatment, imaging and fluid motion control. Polymer nanocomposites are under active investigation for ultra-high energy capacitors2, coupled organic–inorganic nanostructures3 and stimuli-responsive polymer materials4. Traditional fibre-reinforced composites have been extensively studied for mechanical applications. Hybrid nanocomposites have recently attracted considerable attention in high-value-added areas such as energy storage, optical sensors, biomedical material/devices5,6. Their markedly enhanced electrical and thermal conductivity, optical and dielectric response as well as mechanical properties are mainly due to the interfacial “third phase” present between the particle and polymer matrix, enhanced by the high surface-to-volume ratio of NPs5.

A colloidal suspension, whether as a final step in nanofluid formation or the interim step towards a polymer nanocomposite is required to be stable, via Brownian motion, against settling. However, nanofluids are thermodynamically unstable systems and achieving kinetic stability is a necessity7. Frequent particle – particle contact often leads to agglomeration with agglomerate sizes up to several microns8 which compromises material performance. Typically, high intensity sonication is used to break up and reduce such agglomerates while chemical additives, e.g. surfactants, are introduced to avoid re-agglomeration9 or polymer coating is used to encourage steric hindrance10. The addition of stabilisation agents adds to the fluid complexity with regard to subsequent processing and can have detrimental impact on the required NP properties. It often leads to other problems such as complicated processing procedures, undesirable contamination or irreversible deterioration of the surfactant at modest temperatures1. Other methods of stabilisation include electrostatic repulsion where the NPs acquire surface charges once in solution10. However high ionic strength and strongly acidic or basic solutions are often required which can impact on processing and compromise fluid/film properties.

The most promising route to stable dispersion of nanomaterials is considered to be via either direct synthesis in liquid or ‘sequential synthesis–delivery to liquid’ approaches which limit the possibilities for native particle–particle interactions and hence avoid the need for additives and restrictive process windows. Low pressure plasma enhanced CVD coating of NPs with organic layers has been used11 to modify the NP properties and more recently has been shown to improve dispersion characteristics and limit agglomeration12. While in situ sequential NP synthesis followed by polymer coating has been demonstrated13, the use of vacuum plasmas is known to cause difficulties in material collection and handling i.e. scraping from the deposition substrate. To overcome this issue, we have demonstrated direct NP synthesis at atmospheric pressure using a non-thermal equilibrium (low temperature) plasma thus opening the possibilities of direct NP synthesis and delivery to polymer14. Direct synthesis of highly dispersed NPs in liquid through exposure of the liquid to a plasma has also been achieved15. Here the NP dispersion was maintained for many months due to plasma-induced non-equilibrium reactions in the liquid that are as yet not fully elucidated and the subject of on-going investigation15.

In this work, we report on the plasma treatment at atmospheric pressure and resulting characteristics of a ceramic NP–polymer composite comprised of TiO2 and PEDOT:PSS. The latter is the dominant transparent conductive polymer and a potential replacement for ITO in low cost polymer optoelectronic and solar cell technologies. Nanomaterial incorporation (e.g. graphene, nanotubes, SnO2, metal, and ceramics including TiO2) into PEDOT:PSS has been attempted in order to improve its optoelectronic properties. TiO2 is of course an important optoelectronic material16 with a wide variety of applications including those involving incorporation into polymer matrices for solar cells17, dielectrics18, gas sensors19 etc. However the dispersion and agglomeration of nano-sized TiO2 particles in aqueous solutions is particularly problematic20 and the conventional method for fabricating titania–polymer nanocomposites often results in the agglomeration or the segregation of TiO2 particles21. Since the electrical and optical properties of native PEDOT:PSS are expected to be sensitive to the effectiveness of NP incorporation, our approach offers a model system for exploring plasma – liquid – nanoparticle interactions as a route to high performance nanofluids and nanocomposites. In this work we investigate the effect of atmospheric pressure plasma treatment on TiO2 NP–polymer (PEDOT:PSS) colloids and the resultant NP dispersion and properties of the final nanocomposite films. We have focussed on high NP loading as applicable for example in dye sensitized solar cell (DSSC) counter electrodes or polymer LEDs where the film optical properties and/or catalytic activity are also important. We chose a demanding NP loading fraction of ~75% wt. in order to establish that our plasma technique is capable of NP dispersion at challenging and practical NP loading values.

Methods

PEDOT–PSS (1.3 wt% dispersion in H2O) and TiO2 NPs (P25, anatase) with average primary particle size of 25 nm were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. These NPs are widely used as a standard in the research community and in particular for photocatalysis applications22. The as-received TiO2 NPs were highly agglomerated, as is usual with such materials, and the agglomerate size ranged from 10 to 25 μm despite sonication in ethanol for 30 min (see supplementary information, S1). The films were prepared as follows: TiO2 NPs (10 mg) were added to 24.99 g of distilled water followed by sonication (100 W) for 30 min. PEDOT:PSS was sonicated (100 W) for 30 min and then filtered (Millipore 0.2 μm diameter), 253 μL of the filtered polymer was then added to distilled water (25 mL), the mixture was magnetically stirred for 30 min before further processing/testing. The TiO2/distilled water was added to this diluted polymer solution and the mixture was magnetically stirred for 1 hour to produce a TiO2/PEDOT:PSS/water colloid. Films were obtained by drop-casting the colloid mixture onto substrates, followed by drying in air for 6 hours at 25 °C.

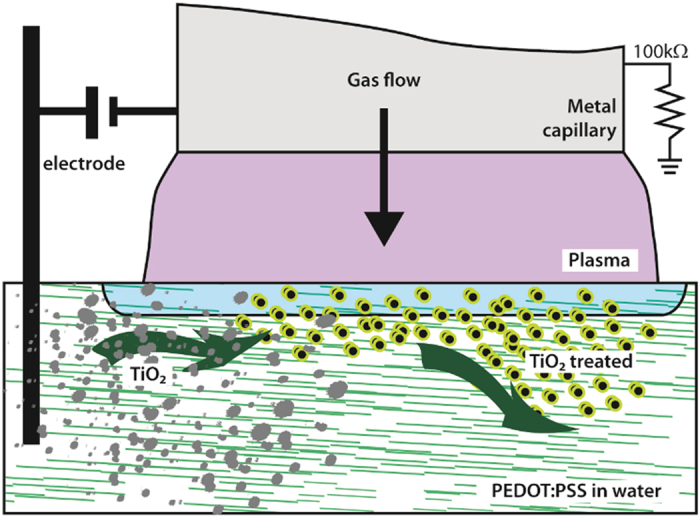

An atmospheric pressure direct-current (DC) plasma was ignited between a stainless steel capillary (with an internal diameter of 0.25 mm and an external diameter of 0.5 mm) and the surface of the TiO2/polymer colloid, Fig. 1. The inert gas flow (pure He) was held constant at 25 sccm. The experimental set up has also been described in detail elsewhere23,24. The distance between the capillary and the plasma–liquid interface was initially adjusted to 0.9 mm. A carbon rod was used as a counter electrode (anode) and kept at a distance of 2 cm from the metal capillary (cathode), which was connected to earth via a 100 kΩ resistor. Microplasma processing was carried out, in open air, for three consecutive periods of 10 minutes. The initial voltage was 1.63 kV and this was progressively reduced to 0.54 kV to maintain a constant current of 0.5 mA. The pH of the solution changed slightly from the starting level of 4.5 to 4.7 after processing.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram depicting the plasma set-up.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Perkin-Elmer Spectrum 2000) was used to determine the surface terminations of the TiO2. UV-Vis spectroscopy (Perkin-Elmer Lambda 35) was used to characterize the optical properties of the samples. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed using a JEOL JEM-2010. The NPs were also investigated before and after processing using scanning electron microscopy (SEM, FEI Quanta 2003D). In order to study the electrical properties of the TiO2/PEDOT:PSS nanocomposites, 40 μL samples were drop-cast onto inter-digitated gold electrodes on glass and allowed to dry for 6 hours at room temperature before measurement. The test structures consisted of 20 pairs of electrodes with a 200 μm spacing, covering an area of 6 mm diameter. The film thickness was ~150 nm. DC current-voltage (IV) plots were obtained using a SemiLab DLS-83D DLTS semiconductor test system with an electrometer capability in the nA range. IV measurements represent the average value across the films.

Results

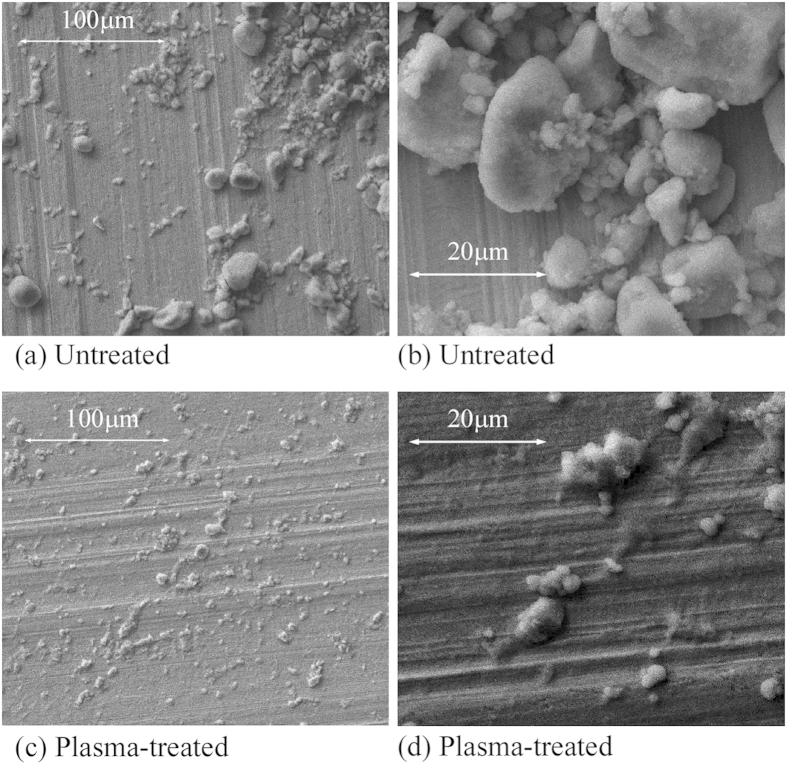

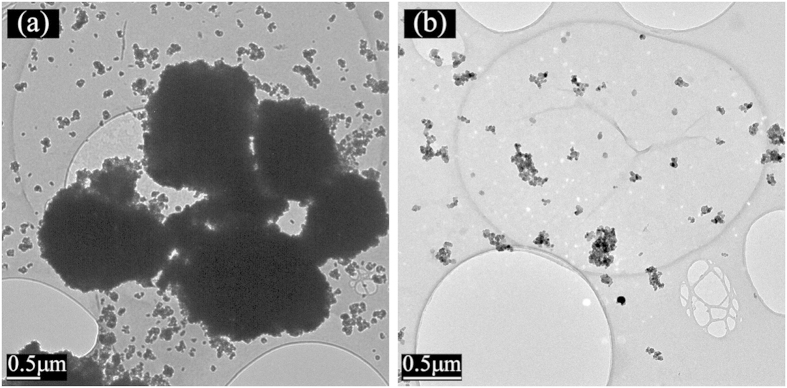

For the plasma treated sample, TiO2 NPs remain stably dispersed throughout the time (a few hours) required for characterisation and analysis, as detailed below, while over the same period, sedimentation of particles is clearly visible for the untreated samples. Some particle sedimentation has been observed, after two days, for the plasma-treated samples. The SEM images of the untreated and plasma-treated samples are shown in Fig. 2a–d. For the untreated sample (Fig. 2a,b), large agglomerates (10–20 μm) with irregular shapes are common, whereas with the plasma-treated samples, Fig. 2c,d, all 10–20 μm agglomerates, observed in the untreated case, have been broken down into much smaller agglomerates (~1 μm and smaller) which appear to be uniformly dispersed within the sample. These particulates consist of multiple 25 nm diameter primary NPs. The improved dispersion and reduced agglomeration is clearly visible in SEM and TEM images, Fig. 3.

Figure 2.

SEM of TiO2 NPs in PEDOT:PSS (a,b) untreated, and (c,d) plasma-treated.

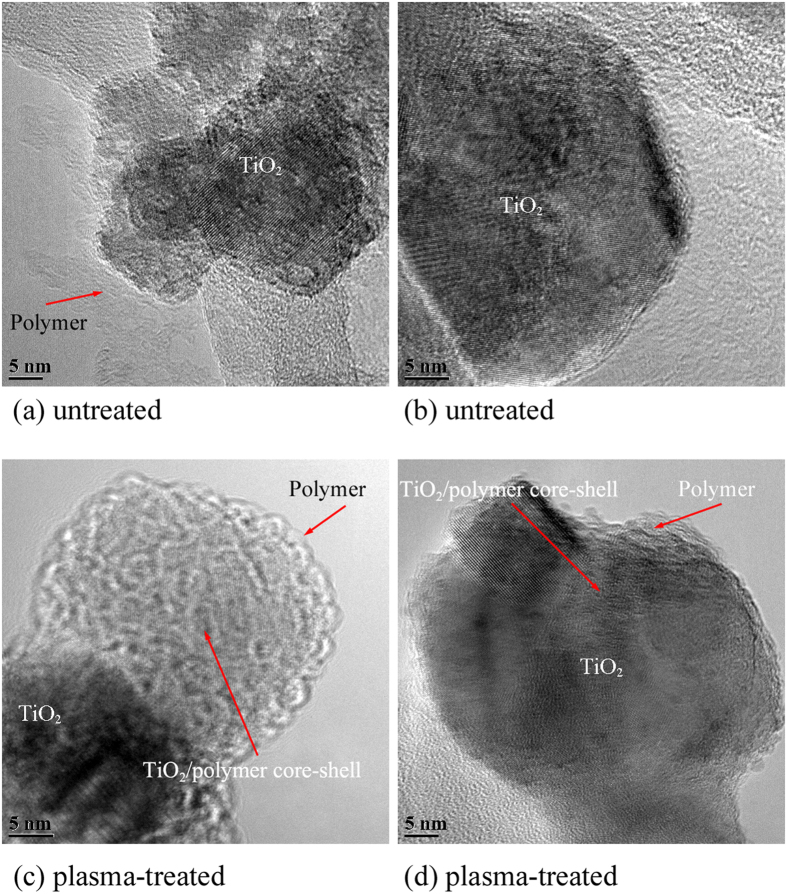

Figure 3.

Typical TEM images of (a) untreated and (b) plasma-treated TiO2 /PEDOT:PSS samples.

TEM analysis has been carried out to further investigate the particle/polymer interaction. Untreated and plasma-treated colloid samples were drop-cast on to TEM sample grids and dried overnight. Figure 3 a shows a typical image of an untreated sample where thick patches (>10 μm) are seen as a result of heavy agglomeration, whereas such features have not been found in the plasma-treated samples. Instead, particles appear to be a lot better dispersed.

In Fig. 4 the high resolution TEM images provide details of the polymer/TiO2 NP interface. For the untreated sample, the analysis over a range of NPs has consistently shown an amorphous polymer region which appears to be segregated from the NPs rather than uniformly encapsulating them (Fig. 4a). Also in some cases, the polymer coating in untreated samples is much less visible (Fig. 4b), indicating weak polymer adsorption on the TiO2 surface. On the other hand, for the plasma-treated sample (Fig. 4c,d), each of the NPs under observation displayed a TiO2 core/polymer shell structure; that is, the TiO2 NPs have been encapsulated by a layer of polymer. In particular, Fig. 4c displays crystalline fringes of a TiO2 NP (lower left) surrounded by an amorphous layer, which is believed to correspond to the polymer encapsulation. On the top right of Fig. 4c the focus of the TEM image is on the surface of a TiO2 NP so that it exhibits the amorphous structure of the polymeric shell. In Fig. 4d, this is also clear as the crystalline structure as well as the amorphous shell are both in focus.

Figure 4.

Typical high resolution TEM images showing details of polymer/TiO2 interface: (a,b) untreated sample and (c,d) plasma-treated sample.

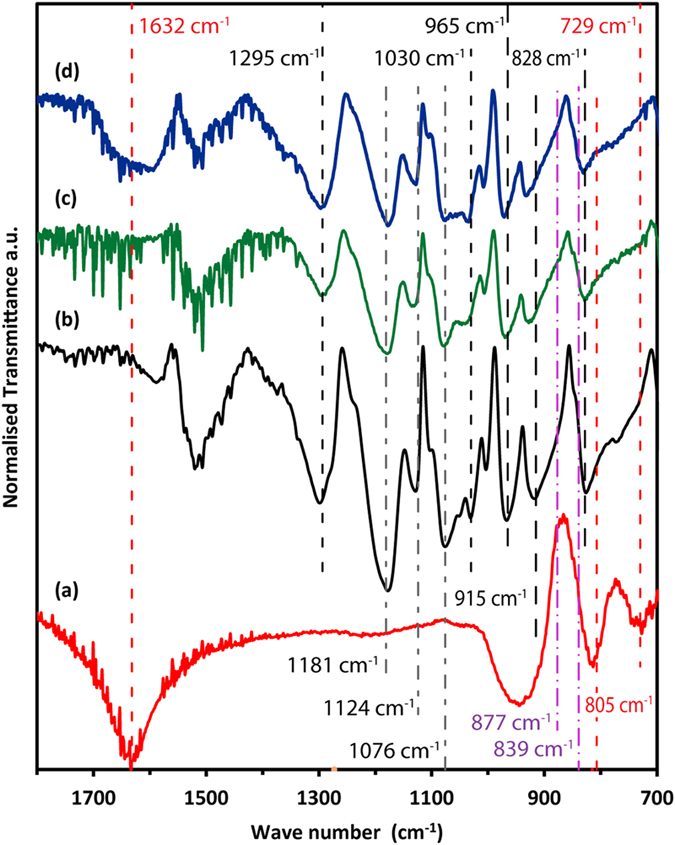

FTIR results of both plasma-treated and untreated samples are shown in Fig. 5. The FTIR signals of pure TiO2 (dry powder, red curve) and PEDOT:PSS (black curve) are also shown for comparison. For all the spectra, the transmission has been normalized to the strongest absorption and baseline correction was also applied. All the samples were drop-cast on silicon substrate and dried for 4 hours before analysis. It can been seen that the FTIR spectrum of pure TiO2 shows the typical characteristic peak at 805 cm−1 for Ti-O25 and 729 cm−1 for O-Ti-O bond26 vibration. The peak at 1632 cm−1 is caused by the O-H bending vibration due to water trapped between NPs possibly in the form of surface coordinated water27.

Figure 5.

Normalized FTIR spectra with baseline correction (a) TiO2, (b) PEDOT:PSS, (c) untreated TiO2/PEDOT:PSS, (d) plasma-treated TiO2/PEDOT:PSS. The characteristic peak locations expected for TiO2, PEDOT:PSS and H2O2 are labeled in red, black and purple dashed lines, respectively (colour plot available online).

The polymer FTIR signal (black in Fig. 5) shows its typical signatures. For instance, the peaks at 965 cm−1, 915 and 828 cm−1 can be assigned to the C-S bond of the thiophene ring in PEDOT28, the S = O vibration near 1295 cm−1, and the O-S-O signal at 1030 cm−1 are identical to those for the sulfonic acid group of the PSS chain. The peaks at 1181 cm−1, 1124 cm−1 and 1076 cm−1 can be attributed to C-O-C bond vibration29. For the untreated sample (green curve in Fig. 5), in which TiO2 particles are dispersed in the PEDOT:PSS/water solution, some characteristic peaks of PEDOT:PSS can been seen. The peak at 729 cm−1 of bulk TiO2 is small but still visible, while the 805 cm−1 absorption might be masked by the polymer signal. The plasma-treated NPs (blue in Fig. 5), as observed with untreated NPs, still show the peaks at 729 cm−1 and the 805 cm−1 of bulk TiO2; the first is weak and the second overlaps with polymer absorption. The sample does not show any absorption above 3000 cm−1, however the peak at 1632 cm−1 has reappeared (overlapped with polymer absorption).

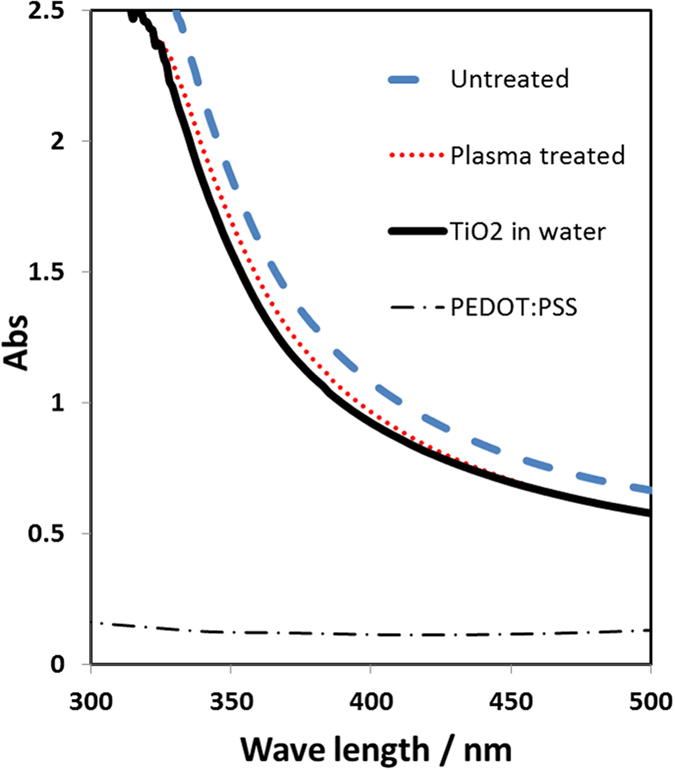

Figure 6 shows the TiO2/PEDOT:PSS colloidal absorption spectra before and after plasma treatment. Using pure water as background for all samples, pure PEDOT:PSS has a limited contribution to UV absorption below 400 nm, and has no absorbance for the visible range (>400 nm). The addition of TiO2 increases the absorption in the UV range (up to 400 nm) due to the strong UV absorbing properties of the NPs. The absorption of TiO2/PEDOT:PSS samples (both plasma treated and untreated) exhibited minor change compared to unmodified TiO2.

Figure 6. UV-vis absorption spectra of TiO2/PEDOT:PSS samples.

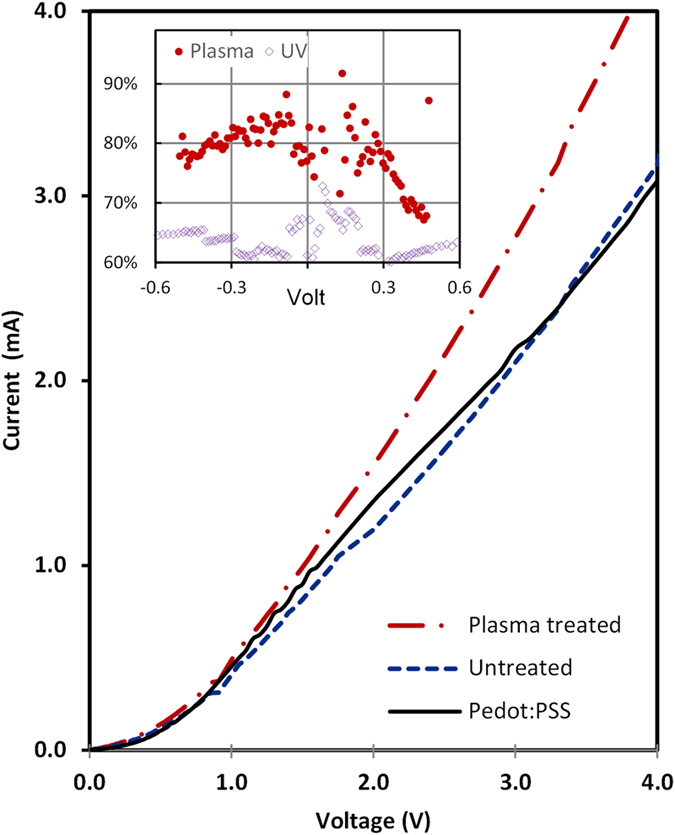

The dark current−voltage (I−V) characteristics of pure PEDOT:PSS (nominal conductivity specification of 1 Scm−1), untreated and plasma-treated TiO2/polymer nanocomposites are shown in Fig. 7. Each sample has been drop-cast onto inter-digitated gold electrodes on glass and allowed to dry for 6 hours before measurements. The conductivity is measured predominantly in the horizontal direction with coplanar electrodes and the composite I-V characteristics are symmetrical and near-linear except around 0 V. The plasma treatment of pure PEDOT:PSS without nanoparticles results in a decrease in conductivity by up to 20%, Fig. 7 (inset), compared to ~35% reduction after UV exposure. The addition of TiO2 NPs to polymer impacts film conductivity to varying degrees. The untreated sample exhibits similar or slightly lower conductivity compared to native polymer whereas after plasma treatment, a significant increase in film conductivity, up to 40%, is observed.

Figure 7. Current−voltage (I−V) characteristics of PEDOT:PSS polymer (dotted), untreated (blue) and plasma treated TiO2/polymer nanocomposites (red).

Discussion

The enhanced dispersion of TiO2 NPs in polymer with negligible re-agglomeration has been achieved using direct plasma exposure of the colloid solution, as evidenced from the SEM and TEM images, prior to film formation. This contrasts considerably with the agglomeration observed in untreated samples and with examples reported in the literature30. The enhanced conductivity observed with the inclusion of a significant concentration of plasma-treated TiO2 NPs provides strong evidence to support the TEM observations and the conclusion that an intimate inorganic-polymer binding has resulted from plasma-induced reactions in the colloid. TiO2 has a natural tendency to agglomerate especially for smaller particles8, to the extent that sonication has limited efficacy10. Immersion in a low ionic strength (IS) solution can help ameliorate this situation by increasing the electrostatic repulsion through enhanced zeta potential and double layer thickness. However the hydrodynamic diameter increases rapidly with IS. Electrostatic stabilisation is possible by adjusting pH values well away from the isoelectric point. Both the pH of native PEDOT:PSS and the initial pH of the TiO2/PEDOT:PSS solution were 4.5. After plasma treatment the pH of the solution increased slightly to 4.7. Depending on IS, this is within the pH range where electrostatic stabilisation is less effective, and in other reports, pH values around 2 were typically required for NP stabilisation in PEDOT:PSS31,32,33,34. The plasma treatment has clearly shown the ability to improve the dispersion of the NPs. We have observed this effect for a range of analogous processes and with various nanomaterials15,35. The nature and mechanism by which the “fragmentation” of agglomerates is achieved, remain unclear however. Chemical interactions through plasma-produced radical species, as well as electrostatic interactions due to the presence of ions/hydrated electrons, may be responsible. The formation of a TiO2/polymer core shell structure observed after plasma treatment is likely to be due to an enhanced electrostatic interaction between polymer and TiO2 NPs induced by plasma processing. FTIR analysis has confirmed that the spectra of PEDOT:PSS/TiO2 samples contain contributions from both TiO2 and PEDOT:PSS. The IR bands for O-S-O (1030 cm−1) and C-S-C (965 and 915 cm−1) vibration28 for untreated sample have been shifted to higher wave numbers (1040 cm−1 for S-O-S, 971 cm−1 and 925 cm−1 for C-S-C) for the plasma treated sample, indicating stronger O-S-O and C-S-C bonds in the polymer with the presence of TiO2.

Chemical reactions are initially induced at the plasma-liquid interface where a range of radicals/compounds and hydrated electrons are produced or absorbed from the gas phase. These are generally due to interactions of the plasma with water molecules and although direct plasma-polymer or plasma-NPs interactions are in principle possible, they remain highly unlikely due to the colloid being mainly composed of water. From these primary chemical products a range of cascaded reactions are possible affecting in different ways the dispersed components, i.e. polymer and NPs. Therefore the surface chemistry of the TiO2 NPs is expected to derive directly from plasma-water induced reactions with negligible effects due to the presence of the polymer, as long as the polymer concentration is kept relatively low. Plasma-water interactions are currently the subject of specialized experimental and theoretical efforts36, and the direct measurement of OH and other plasma-generated radicals involves complex measurements which, to date, have not produced accurate results. Nevertheless the plasma production of OH radicals and H+ ions is well established37,38. Plasma-water interactions have been also found to produce H2O239, however interaction between TiO2 and H2O2 is not thought to be significant in our case as the characteristic peaks of H2O2 at 839 cm−1 and 877 cm−1 40 were not observed. This finding is consistent with our previous studies where we compared H2O2 processing alone versus plasma-liquid processes for silicon NPs with41 or without a polymer in the aqueous solution42.

From the FTIR spectra, the sharp-peak seen at 1630 cm−1 for powder TiO2 is indicative of weakly bound hydrogens on neutral (i.e. uncharged) surfaces43. This is also confirmed by the typical O-H absorption of water that gives rise to a broad peak above 3000 cm−1; in particular the surface charges produce a local electric field that affects the orientation of water molecules so that the peak tends to shift to higher wavenumbers (>3500 cm−1) for negatively charged surfaces and to lower wavenumber (<3200 cm−1) for positively charged surfaces. However the peak at 1632 cm−1 is generally much weaker than the 3000–3600 cm−1 absorption for trapped water and therefore we expect that the contribution for this absorption also comes from O-H vibration in Ti-OH terminations27, which may also explain the broad absorption above 900 cm−1. We can therefore conclude that pristine NPs present typical Ti-O-Ti surfaces with in part Ti-OH terminations and also adsorbed trapped water. TiO2 surface groups can be either singly, doubly or triply coordinated (TiO, Ti2O, Ti3O), having a lower coordination with Ti4+ than the oxygen atoms in the solid44. The missing charge may be compensated by the uptake of one (Ti2O(H)) or two protons (TiOH(H)). It has been reported that TiO2 NPs dispersed in water are initially covered by hydroxyl group and different surface interactions can take place under acidic or alkaline conditions45. With respect to polycrystalline TiO2 i.e. P25 (rich in anatase) as used here, the Ti3O surface oxygen atoms cannot be protonated in our tested pH range and therefore are not active with respect to the charging behaviour46. The FTIR spectrum of pure TiO2 shows the typical characteristic peaks at 805 cm−1 for Ti-O25 and 729 cm−1 for O-Ti-O bond26 vibration. These peaks are weaker in composite samples due to the presence of the polymer which reduces the FTIR light penetration depth in the film. When TiO2 NPs are dispersed in aqueous medium a reduction of the peak at 1632 cm−1 is observed indicating the deprotonation of Ti-OH terminations and a reduction in the number of surface trapped water molecules due to the hydrophobic character of resulting TiO− surfaces. However, after plasma treatment the peak at 1632 cm−1 reappears (overlapped with polymer absorption) suggesting a re-protonation of some Ti-O sites. This increase in the surface density of Ti-OH terminations are, we believe, due to the presence of OH radicals and H+ ions from the plasma where the former cleave Ti-O-Ti bonds and the latter react to form Ti-OH via TiO− + H+ → Ti-OH. Due to the high surface density of Ti-OH, condensation of adjacent terminations forms Ti-O-Ti surfaces. Depending on the IS of the PEDOT:PSS/H2O, at a pH of 4.7 we would expect significant protonation of TiO sites although most would still remain non-protonated (therefore negatively-charged). Ti2O sites are however almost fully protonated (positively-charged). At low pH, the positively charged protonated sites, Ti2OH and TiOH, would therefore dominate and could electrostatically enhance the negatively-charged PSS species bonding. Also the hydrophilic character of protonated surfaces would enhance the polymer – nanoparticle interaction.

In this work, low conductivity (~1 S cm−1) native treated PEDOT:PSS (no additives) was used to as starting material to highlight the possible impact of NP addition on conductivity which can be expected to be sensitive to the NP dispersion and the quality of the interface with the polymer. The NP fraction was ~75% wt., much higher than typically reported (20% wt.)17,47. However, the resultant dispersion and smooth surface, as observed in Fig. 2, is a strong indicator that polymer disruption and the formation of significant NP networks has not occurred. The use of TiO231 and other n-type NPs (e.g. α-Fe2O332) for conductivity modulation of PEDOT:PSS has been reported along with the tailoring of TiO2 electronic properties (reduced bandgap, fermi-level shifting) through surface modification with polymer/dye interfaces33,48 and doping16. It is unlikely that significant electronic structure modification has occurred in our case due to plasma treatment as very minor change (except intensity) was observed in UV-vis absorption spectra. Yoo et al.30,47 directly mixed TiO2 NPs with PEDOT:PSS to form a densely agglomerated composite film displaying diode-like characteristics, with an increase in conductivity for forward bias only, similar to a pure NP film. Sakai et al.31 reported no conductivity changes for PEDOT-PSS/TiO2 NP composite films, fabricated with layer-by-layer assembly, except after irradiation by light. Semaltianos et al.49 observed a factor of two increase in conductivity using 10% wt. of ZnO NPs (~5 nm). Sun et al.34 noted a decrease in PEDOT-PSS conductivity with the inclusion of Fe3O4 NPs up to 20% wt. which was attributed to the insulating nature of the particles. However Raccis et al.32 observed that, within a very narrow range of concentrations (~1.2%), the conductivity of PEDOT-PSS could be increased up to eight-fold after NP inclusion. Understanding PEDOT:PSS conduction mechanisms is a significant challenge in the search for enhanced or selectable conductivity and resistance to degradation. PEDOT:PSS conduction is not fully understood but is strongly linked to film morphology, which in spin-cast films is thought to consist of quasi-metallic grains rich in PEDOT surrounded by a semi-insulating PSS shell50 or as filamentary PEDOT structures51. Experimental observations52 indicate these grains to be of oblate spheroid shape, approximately 20 nm to 30 nm in diameter and 4 nm to 6 nm in height formed in layers. Conduction is highly anisotopic due to the much narrower grain-grain gap along the in plane diameter direction, compared to the orthogonal. However, quasi-1D variable range hopping characteristics have often been found to fit the observed anisotropic conductivity which van de Ruit et al.53 concluded being due to the formation of filamentary PEDOT networks operating close to the percolation threshold. High conductivity PEDOT:PSS54, up to 3000 S cm−1, is thought to be determined by enhanced hopping conduction between grains due to the greater grain agglomeration and crystal size as a result of additives51 or the enhancement of filamentary connectedness well above percolation threshold due to processing53. As the PSS content is reduced, an apparent percolation threshold is reached, implying a connected network of highly conducting PEDOT:PSS complexes has been established within the poorly conducting PSS matrix. The number of such connected paths would then determine the macroscopic mobility51,53. The mobility may also be enhanced via conformational changes, e.g. by adding compounds with two or more polar groups, where the PEDOT chains shift from coiled to expanded-coil or linear form. The microplasma treatment of pure PEDOT:PSS has led to a decrease in conductivity by ~20% which is likely due to low dose UV-exposure from the plasma. We have observed polymer conductivity degradation after direct UV exposure over an extended period, as has been reported previously for UV-exposure in air55 (see also Fig. 7. inset). The detailed reaction mechanisms between the plasma induced reactive species and the polymer molecules remain unclear. However it is clear that the enhanced conductivity of the composite film is not due to plasma-induced enhancement of the polymer conductivity alone.

As an n-type conductor in a p-type material, the TiO2 NPs would be isolated from the conductive networks and not be expected to automatically enhance the polymer conductivity. Charge confinement on the NP surface56,57 and the resultant surface electric field extending into the polymer between NPs, would impact on polymer mobility through a complex exponential dependence on field strength32. Where the fields are moderate or low, the mobility would be enhanced and the degree of enhancement would be dependent on NP-NP spacing, i.e. volume density. The inclusion of NPs up to 40% by volume in this case, may also facilitate greater network connectivity as the polymer volume is reduced. NP-PEDOT interaction may also lead to conformational changes that affect the intrinsic polymer mobility. Raman studies of ZnO in PEDOT:PSS49 indicate a change from a coil conformation to a linear form due to the strongly electronegative oxygen atom of the hydroxyl groups (–OH) on the NPs surface which may form hydrogen bonds with the sulphur cation (S+) of the thiophene ring of PEDOT thus weakening the electrostatic interaction between PEDOT and PSS. The experimental evidence for conductivity modification by NPs across different materials is, as outlined above, inconsistent. In this work, plasma-treatment of the TiO2/polymer colloid has demonstrated conductivity enhancement at high NP concentrations and this suggests considerable scope for optimising factors such as loadings, in order to tailor conductivity, optical and catalytic properties without disrupting the polymer matrix.

Conclusion

In this report, we have demonstrated a green and rapid approach to disperse TiO2 NPs in conductive PEDOT:PSS aqueous solution. It is found that the use of room temperature atmospheric pressure DC plasma can effectively breakdown TiO2 agglomerates and introduce surface modification leading to improved dispersion and stability of TiO2 NPs. The enhanced electrical conductivity of plasma treated nanocomposites has been attributed to the better particle/polymer interaction, enhanced particle dispersion and better film mechanical stability. This work reveals the potential of low temperature atmospheric pressure plasma processing in addressing the challenging issue of homogeneous dispersion of inorganic particles into a polymer matrix and tailoring of the nano-to-macro structure of hybrid nanocomposites.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Liu, Y. et al. Enhanced Dispersion of TiO2 Nanoparticles in a TiO2/PEDOT:PSS Hybrid Nanocomposite via Plasma-Liquid Interactions. Sci. Rep. 5, 15765; doi: 10.1038/srep15765 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by contributions from InvestNI (n.PoC-325), EPSRC (EP/K022237/1), Dept. Employment & Learning, N. Ireland (US-IRL 013) and the University of Ulster Research Challenge Fund. SA acknowledges the support of the University of Ulster Vice-Chancellor’s Research Studentship. All authors acknowledge the COST action and its funding support.

Footnotes

Author Contributions Y.L. and D.S. contributed equally to this work. D.S. and P.M. conceived the idea of the work, Y.L. and D.S. conducted the experiments and wrote the manuscript, S.A. conducted the TEM, J.P., S.M. and G.J. contributed to the microplasma experiments, M.M. and R.Z. contributed to the FTIR experiments and analysis, W.F.L. contributed to the data analysis and discussion. D.M. and P.M. contributed to the results, discussion and manuscript writing. All authors reviewed the manuscript. The authors claim no competing financial interests for this work.

References

- Taylor R. et al. Small particles, big impacts: A review of the diverse applications of nanofluids J. Appl. Phys. 113, 011301 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. et al. Ultrahigh Energy Density of polymer nanocomposites containing BaTiO3@TiO2 nanofibers by atomic-scale interfacee Adv. Mater. 27, 819–824 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheele M., Brutting W. & Schreiber F. Coupled organic-inorganic nanostructures (COIN) Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 97–111 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt D. J. et al. Electrochemically controlled swelling and mechanical properties of a polymer nanocomposite ACS Nano 3, 2207–2216 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hybrid Nanocomposites for Nantechnology - electronic, optical, magnetic and biomedical Applications. (ed. Lhadi, M.) (Springer, New York, 2009).

- Sanchez C., Julian B., Belleville P. & Popall M. Applications of hybrid organic-inorganic nanocomposites J. Mater. Chem. 15, 3559–3592 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Angayarkanni S. A. & Philip J. Role of Adsorbing moieties on thermal conductivity and associated properties of nanofluids J. Phys. Chem. C 117, 9009–9019 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D. et al. Influence of Material Properties on TiO2 Nanoparticle Agglomeration PLOS ONE 8, e81239 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Othman S. H., Rashid S. A., Ghazi T. I. M. & Abdullah N. Dispersion and stabilization of photocatalytic TiO2 nanoparticles in aqueous suspension for coatings applications J. Nanomat. 2012, Article ID 718214 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J. K., Oberdorster G. & Biswas P. Characterization of size, surface charge, and agglomeration state of nanoparticle dispersions for toxicological studies J. Nanopart Res. 11, 77–89 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Shi D. et al. Uniform deposition of ultrathin polymer films on the surfaces of Al2O3 nanoparticles by a plasma treatment, Appl. Phys. Lett. 78 (9), 1243–1245 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- He W., Guo Z., Pu Y., Yan L. & Si W. Polymer coating on the surface of zirconia nanoparticles by inductively coupled plasma polymerization, Appl. Phys. Lett. 85 (6), 896–898 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Tavares J., Swanson E. J. & Coulombe S. Plasma synthesis of coated metal nanoparticles with surface properties tailored for dDispersion Plasma Processes & Polym. 5, 759–769 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Askari S., Levchenko I., Ostrikov K., Maguire P. & Mariotti D. Crystalline Si nanoparticles below crystallization threshold: Effects of collisional heating in non-thermal atmospheric-pressure microplasmas Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 163103 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Mariotti D., Švrček V., Hamilton J. W. J., Schmidt M. & Kondo M. Silicon nnocrystals in liquid media: optical properties and surface stabilization by microplasma-induced non-equilibrium liquid chemistry Adv. Funct. Mater. 22, 954–964 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Kapilashrami M., Zhang Y., Liu Y.-S., Hagfeldt A. & Guo J. Probing the optical property and electronic structure of TiO2 nanomaterials for renewable energy applications Chem. Rev. 114, 9662–9707 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiaugree W. et al. Optimization of TiO2 nanoparticle mixed PEDOT–PSS counter electrodes for high efficiency dye sensitized solar cell J. Non-Crystalline Solid. 358, 2489–2495 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Fleming R. J., Pawlowski T., Ammala A., Casey P. S. & Lawrence K. A. Electrical conductivity and space charge in LDPE containing TiO2 nanoparticles” IEEE T. Dielect. El. In. 12, 745–753 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Zampetti E. et al. TiO2 nanofibrous chemoresistors coated with PEDOT and PANi blends for high performance gas sensors Procedia Eng. 47, 937- 940 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Angayarkanni S. A. & John P. Effect of nanoparticles aggregation on thermal and electrical conductivities of Nanofluids J. Nanofluids 3, 17–25 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J. K., Chen D. R. & Biswas P. Synthesis of nanoparticles in a flame aerosol reactor with independent and strict control of their size, crystal phase and morphology Nanotechnology 18, 285603 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. & Mao S. S. Titanium Dioxide Nanomaterials: Synthesis, properties, modifications, and applications Chem. Rev. 107, 2891–2959 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Švrček V., Mariotti D. & Kondo M. Microplasma-induced Surface Engineering of Silicon Nanocrystals in Colloidal Dispersion Appl. Phys. Lett 97, 161502 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Mariotti D. & Sankaran R. M. Perspectives on atmospheric-pressure plasmas for nanofabrication, J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 44 174023 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos D. C. L. et al. Infrared Spectroscopy of Titania sol-gel coatings on 316L stainless steel Mat. Sci. & Appl. 2, 1375–1382 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Corobea M. et al. Titanium functionalizing and derivatizing for implantable materials osseointegration properties enhancing, Dig. J. Nanomat. Bio. 9, 1339–1347 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Soler-Illia G. J. D. A., Louis A. & Sanchez C. Synthesis and characterization of mesostructured Titania-Based materials through evaporation-induced self-assembly Chem. Mat. 14, 750–759 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Abdiryim T., Ali A., Jamal R., Osman Y. & Zhang Y. A facile solid-state heating method for preparation of poly(3,4-ethelenedioxythiophene)/ZnO nanocomposite and photocatalytic activity Nanoscale Res. Lett. 9, 89 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam M. M. et al. Liquid crystalline graphene oxide/PEDOT:PSS self-assembled 3D architecture for binder-free supercapacitor electrodes Front. Energy Res. 2, 31 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Yoo K. H., Kang K. S., Chen Y., Han K. J. & Kim J. The TiO2 nanoparticle effect on the performance of a conducting polymer Schottky diode Nanotechnology 19, 505202 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai N., Prasad G. K., Ebina Y., Takada K. & Sasaki T. Layer-by-Layer Assembled TiO2 nanoparticle/PEDOT-PSS composite films for switching of electric conductivity in response to ultraviolet and visible light, Chem. Mat. 18(16), 3596–3598 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Raccis R., Wortmann L., Llyas S., Schlafer J., Mettenborger A. & Mathur S. Dipole-induced conductivity enhancement by n-type inclusion in a p-type system: α-Fe2O3-PEDOT:PSS nanocomposites, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 15597–15607 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janković I. A., Šaponjić Z. V., Džunuzović E. S. & Nedeljković J. M. New hybrid properties of TiO2 nanoparticles surface modified with catecholate type ligands Nanoscale Res. Lett. 5, 81–88 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D. C. & Sun D. S. The synthesis and characterization of electrical and magnetic nanocomposite: PEDOT/PSS–Fe3O4, Mat. Chem. Phys. 118, 288–292 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Svrcek V. et al. Dramatic Enhancement of Photoluminescence Quantum yields for surface-engineered Si nanocrystals within the solar spectrum Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 6051–6058 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Bruggeman P. & Leys C. Non-thermal plasmas in and in contact with liquids J. Phys. D. 42, 053001 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Rumbach R., Bartels D. M., Sankaran R. M. & Go D. B. The solvation of electrons by an atmospheric-pressure plasma Nature Comms. 6, 7248 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava N. & Wang C. Effects of water addition on OH radical generation and plasma properties in an atmospheric argon microwave plasma jet J. Appl. Phys. 110, 053304 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Patel J., Nemcova L., Maguire P., Graham W. G. & Mariotti D. Synthesis of surfactant-free electrostatically stabilized gold nanoparticles by plasma-induced liquid chemistry Nanotechnology. 24, 245604 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura R. & Nakato Y. Primary Intermediates of Oxygen photoevolution reaction on TiO2 (rutile) particles, revealed by in situ FTIR absorption and photoluminescence measurements J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 1290–1298 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra S. et al. Improved optoelectronic properties of silicon nanocrystals/polymer nanocomposites by microplasma-induced liquid chemistry J. Phys. Chem. C 117, 23198–23207 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Mitra S. et al. Microplasma-induce liquid chemistry for stabilizing of silicon nanocrystals optical properties in water Plasma Processes Polym. 11, 158–163 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Connor P. A., Dobson K. D. & McQuillan A. J. Infrared spectroscopy of the TiO2/aqueous solution interface Langmuir 15, 2402–2408 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Hiemstra T., Venema P. & Van Riemsdijk W. H. Intrinsic proton affinity of reactive surface groups of metal (hydr)oxides: the bond valence principle J. Colloid & Interface Sci. 184, 680–692 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suttiponparnit K. et al. Role of surface area, primary particle size, and crystal phase on titanium dioxide nanoparticle dispersion properties Nanoscale Res. Lett. 6, 27 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourikas K., Kordulis C. & Lycourghiotis A. Titanium dioxide (anatase and rutile): surface chemistry, liquid–solid interface chemistry, and scientific synthesis of supported catalysts Chem. Rev. 114, 9754–9823 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo K. H., Kang K. S., Chen Y., Han K. J. & Kim J. The effect of TiO2 nanoparticle concentration on conduction mechanism for TiO2-polymer diode Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 192113 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. & Cole J. M. Adsorption Properties of p-Methyl Red Monomeric-to-Pentameric Dye Aggregates on Anatase (101) Titania Surfaces: First-Principles Calculations of Dye/TiO2 Photoanode Interfaces for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 15760–15766 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semaltianos N. G. et al. Modification of the lectrical properties of PEDOT:PSS by the incorporation of ZnO nanoparticles synthesized by laser ablation, Chem. Phys. Lett. 484, 283–289 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Nardes A. M., Kemerink M. & Janssen R. A. J. Anisotropic hopping conduction in spin-coated PEDOT:PSS thin films, Phys. Rev. B. 76 (8), 085208 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Yamada Y., Yamashita M., Sasaki T., Okuzaki H. & Otani C. Carrier transport of conducting polymer PEDOT:PSS investigated by temperature dependence of THz and IR spectra, presented at the 39th International Conference on the Infrared, Millimeter, and Terahertz waves (IRMMW-THz), Tucson, AZ, USA. IEEE. ( 10.1109/IRMMW-THz.2014.6956089)(2014, Sep 14–19) . [DOI]

- Nardes A. M. et al. Microscopic understanding of the anisotropic conductivity of PEDOT:PSS thin films Adv. Mat. 19, 1196–1200 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- van de Ruit K. et al. Quasi-One Dimensional in-plane conductivity in filamentary films of PEDOT:PSS, Adv. Funct. Mat. 23, 5778–5786 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Park H.-S., Ko S.-J., Park J.-S., Kim J. Y. & Song H.-K. Redox-active charge carriers of conducting polymers as a tuner of conductivity and its potential window, Sci. Rep. 3, 2454 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing Y. J. et al. UV irradiation induced conductivity improvement in poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrenesulfonate) film, Sci. China Technol. Sci. 57, 44–48 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Gu G. R. et al. Conductivity of nanometer TiO2 thin films by magnetron sputtering, Vacuum 70, 17–20 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Nardes A. M. et al. Conductivity, work function, and environmental stability of PEDOT:PSS thin films treated with sorbitol, Org. Electron. 9, 727–734 (2008). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.