Abstract

Salmonella enterica is one of the most common causes of foodborne illness in the United States. Although salmonellosis is usually self-limiting, severe infections typically require antimicrobial treatment and ceftriaxone, an extended-spectrum cephalosporin, is commonly used in both adults and children. Surveillance conducted by the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS) has shown a recent increase in extended-spectrum cephalosporin (ESC) resistance among Salmonella Heidelberg isolated from food animals at slaughter, retail meat, and humans. ESC resistance among Salmonella in the United States is usually mediated by a plasmid-encoded blaCMY β-lactamase. In 2009, we identified 47 ESC resistant blaCMY-positive Heidelberg isolates from humans (n=18), food animals at slaughter (n=16), and retail meats (n=13) associated with a spike in the prevalence of this serovar. Almost 90% (26/29) of the animal and meat isolates were isolated from chicken carcasses or retail chicken meat. We screened NARMS isolates for the presence of blaCMY, determined whether the gene was plasmid-encoded, examined pulsed-field gel electrophoresis patterns to assess the genetic diversities of the isolates, and categorized the blaCMY plasmids by plasmid incompatibility groups and plasmid multi-locus sequence typing. All 47 blaCMY genes were found to be plasmid encoded. Incompatibility/replicon typing demonstrated that 41 were IncI1 plasmids, 40 of which only conferred blaCMY associated resistance. Six were IncA/C plasmids that carried additional resistance genes. Plasmid multi-locus sequence typing (pMLST) of the IncI1-blaCMY plasmids showed that 27 (65.8%) were sequence type (ST) 12, the most common ST among blaCMY-IncI1 plasmids from Heidelberg isolated from humans. Ten plasmids had a new ST profile, ST66, a type very similar to ST12. This work showed that the 2009 increase in ESC resistance among Salmonella Heidelberg was caused mainly by the dissemination of blaCMY on IncI1 and IncA/C plasmids in a variety of genetic backgrounds, and likely not the result of clonal expansion.

Introduction

Salmonella enterica is a common cause of foodborne illness in the United States, causing approximately 1.2 million cases of salmonellosis each year (Scallan E 2011). Although salmonellosis is usually self-limiting, severe infections leading to invasive disease typically requires treatment with extended-spectrum cephalosporins (ESC) or fluoroquinolones. ESCs are the treatment of choice for children (Forsythe and Ernst 2007).

The most common non-typhoidal Salmonella serotypes causing human disease in the U.S. are Enteritidis, Typhimurium, Newport, Javiana, and Heidelberg. However, serotypes Typhimurium, Enteritidis, and Heidelberg tend to be more invasive and are the most common serotypes isolated from blood (Crump, Medalla et al. 2011). Invasive Salmonella are more likely to require antimicrobial treatment and bloodstream isolates are more likely to be antimicrobial resistant to one or more drugs, further complicating treatment (Crump, Medalla et al. 2011). Salmonella serotype Heidelberg is one of the most common serotypes isolated from human cases of salmonellosis, Heidelberg is more common among bloodstream infections, and it is more likely to be resistant to antimicrobials. In 2009, Salmonella Heidelberg increased significantly to become the third most common serotype among retail meat and food animal isolates, and fifth most common among isolates from humans (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2009; United States Department of Agriculture 2009; United States Food and Drug Administration (A) 2009).

ESC resistance among Salmonella in the United States is associated with the production of an AmpC-like (CMY) β-lactamase, conferred mostly by blaCMY genes (Philippon, Arlet et al. 2002). CMY β-lactamases confer resistance to ESCs and β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations (Dunne, Fey et al. 2000). The blaCMY gene is usually encoded on various plasmids, which can be distinguished by their incompatibility/replication features (Carattoli, Tosini et al. 2002; Carattoli, Bertini et al. 2005; Frye, Fedorka-Cray et al. 2008; Zhao, White et al. 2008; Folster, Pecic et al. 2010; Sjolund-Karlsson, Rickert et al. 2010). Plasmids with the same replication controls are incompatible and can therefore be grouped into several replicon (Inc) groups. Replicon type IncA/C and IncI1 are the predominant plasmid types encoding CMY β-lactamases (Hopkins, Liebana et al. 2006; Welch, Fricke et al. 2007; Baudry, Mataseje et al. 2009; Folster, Pecic et al. 2010; Folster, Pecic et al. 2011). IncI1 plasmids are commonly found among poultry-associated Salmonella serotypes including Heidelberg (Folster, Pecic et al. 2010; Folster, Pecic et al. 2011).

In the United States, antimicrobial resistance among non-typhoidal Salmonella is monitored by the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring Systems (NARMS), a collaboration among the Food and Drug Administration Center for Veterinary Medicine (FDA-CVM), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) which performs surveillance on Salmonella isolates from retail meats, food animals, and humans, respectively. Animal isolates originate from federally inspected slaughter and processing plants throughout the United States, retail meat isolates are collected from 11 states, including 10 Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet) sites and 1 state public health laboratory, and human isolates are collected from 54 NARMS-participating public health laboratories from all 50 states (United States Food and Drug Administration (B) 2009). The purpose of this surveillance is to monitor trends in antimicrobial resistance among different sources, and geographic locations over time.

Compared with 2008, 2009 showed a substantial increase in resistance to ceftriaxone (MIC ≥ 4 μg/ml) among Heidelberg isolated from retail meats (from 9.3% to 27.3%) food animals (9.4% to 17.3%), and humans (8% to 20.9%) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2009; United States Department of Agriculture 2009; United States Food and Drug Administration 2009). The increase in ESC resistance among isolates from humans appeared mainly in western states (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2009). To determine whether this increase was driven by the emergence of a new variant of ESC-resistant Heidelberg, we screened NARMS isolates for the presence of blaCMY, determined whether the gene was plasmid-encoded, examined pulsed-field gel electrophoresis patterns to assess the genetic diversities of the isolates, and categorized the blaCMY plasmids by plasmid incompatibility groups and plasmid multi-locus sequence typing.

Materials and methods

Isolate collection and testing

Salmonella isolates from ill persons were obtained from specimens submitted to clinical laboratories in the United States and subsequently forwarded to state public health laboratories. Participating state public health laboratories serotyped and submitted every twentieth non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS) to the CDC NARMS laboratory for susceptibility testing. NARMS retail meat monitoring was conducted by the United States FDA-CVM in collaboration with FoodNet (http://www.cdc.goc/foodnet/) as previously described (Zhao, White et al. 2008). Retail meat sources include chicken breasts, pork chops, ground beef, and ground turkey purchased from retail stores in the 10 FoodNet sites plus the Pennsylvania state public health laboratory. NARMS monitoring of food animals at slaughter was conducted by the USDA Bacterial Epidemiology and Antimicrobial Resistance Research Unit (BEAR) of the Agricultural Research Service (ARS) as previously described (Frye, Fedorka-Cray et al. 2008). Sampling is conducted on chickens, pigs, cattle, and turkeys at federally inspected slaughter and processing plants as part of the USDA Food Safety Inspection Service inspection program. Broth microdilution (Sensititre®, Trek Diagnostics, Westlake, OH) was used to determine the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) for 15 antimicrobial agents; amikacin, ampicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, cefoxitin, ceftiofur, ceftriaxone, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, kanamycin, nalidixic acid, streptomycin, sulfisoxazole, tetracycline, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Resistance was defined by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) interpretive standards, when available (CLSI 2011). For streptomycin, where no CLSI interpretive criteria for human isolates exist, the resistance breakpoint is 64 μg/ml (United States Food and Drug Administration (B) 2009). Testing was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions and the following quality control strains; E. coli ATCC 25922, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, E. coli ATCC 35218, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853.

PCR amplification of blaCMY

For each isolate, DNA template for PCR was prepared by lysing the bacteria at 95°C and collecting the supernatant following centrifugation for 10 min at 20,000 g (Sorvall RC5B Plus, SS-34 rotor, Thermo Fischer Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA). PCR reactions contained 2× HotStar PCR Master Mix (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA), 0.4μM of each primer, 5μl template DNA and sterile PCR water to a final volume of 50μl. Thermal cycling was performed using the following conditions: 15 min at 95˚C, followed by 30 cycles of 95˚C for 30 s, 56˚C for 30 s and 72˚C for 90 s. To determine the presence of blaCMY genes, primers ampC1 (5′-ATGATGAAAAAATCGTTATGC-3′) and ampC2 (5′-TTGCAGCTTTTCAAGAATGCGC-3′) were used (Winokur, Vonstein et al. 2001).

Plasmid purification and characterization

Purified plasmid DNA was used to transform laboratory E. coli, separate the blaCMY plasmids from other plasmid types prior to replicon typing, and for plasmid multi-locus sequence typing (pMLST). Plasmids were purified using the QiaFilter Midi kit (Qiagen Inc.), following a modified manufacturer's protocol (Folster, Pecic et al. 2010). Electroporation of each plasmid into E. coli DH10B Electromax competent cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was performed as previously described (Folster, Pecic et al. 2010). Cells were plated on LB agar plates containing 100 mg/L of ampicillin or 4 mg/L ceftriaxone (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Plasmids were re-purified from a single blaCMY PCR-positive transformant to isolate a single plasmid from each isolate. Purification was performed as described above with the additional modification of growing the cells overnight in 25 ml of LB broth with 100 μg/ml of ampicillin or 4 μg/ml ceftriaxone. Plasmid PCR-based replicon typing (PBRT) was performed as previously described (Carattoli, Bertini et al. 2005). Plasmid multi-locus sequence typing was performed on IncI1 plasmids as previously described (Garcia-Fernandez, Chiaretto et al. 2008). Sequencing was performed using Big Dye version 3.1 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and sequence reactions were cleaned with Centri-sep plates (Princeton Separations, Adelphia, NJ). The reactions were electrophoresed through POP-7 polymer (Applied Biosystems) on a 3730 DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) equipped with a 48-capillary, 50 cm array. Sequence analysis was performed using Lasergene 8 software (DNASTAR Inc, Madison, WI). Sequences were submitted to the plasmid multi locus sequence type (pMLST) web page (http://pubmlst.org/plasmid/) and the ST type was determined.

Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE)

Two enzyme (XbaI and BlnI) PFGE was performed according to the CDC PulseNet protocol and all PFGE profiles generated were submitted to the PulseNet national database administered by CDC (NARMS-FDA and NARMS-CDC) or USDA VetNet (NARMS-USDA) (Ribot, Fair et al. 2006; Jackson, Fedorka-Cray et al. 2007). Gel images were captured using the GelDoc XR system (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and Quantity one 1-D analysis software (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Pattern analysis and UPGMA dendrogram generation were performed using BioNumerics software (Applied Maths, Saint-Martens-Latem, Belgium) with the Dice coefficient and tolerance of 1.5%.

Results

Identification of blaCMY-positive Salmonella ser. Heidelberg isolates

NARMS received and performed antimicrobial susceptibility testing on 223 isolates of Salmonella Heidelberg from food animals, retail meat, and humans in 2009. Of these, 47 isolates (21.1%) displayed resistance to ceftriaxone, ceftiofur, and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, suggesting the presence of a blaCMY allele. Isolates from humans (n=18) made up the largest proportion of these resistant isolates (38.3%). Two-thirds of these isolates (n=12) were obtained from patients in western states (CA, OR, and WA) over a five month period. Thirteen of the human isolates were from male patients and five were from females. The median age was 26. Among animal isolates, 96.1% (74/77) of the Heidelberg isolates and 92.3% (12/13) of the resistant isolates were obtained from chickens. Among retail meat isolates, 80.4% (45/56) of Heidelberg isolates were obtained from chicken breast samples while 17.9% came from ground turkey. Most of the cephalosporin-resistant isolates (14/16; 87.5%) were obtained from chicken breast samples. PCR-analysis confirmed that all 47 ESC-resistant isolates were positive for blaCMY.

Characterization of the blaCMY plasmids

Plasmids were purified from the transformants and typed by PCR-based replicon typing (PBRT). Forty-one of 47 blaCMY plasmids were replicon type IncI1 and the remaining six plasmids were replicon type IncA/C (Table 1). The six IncA/C plasmids were identified among two human isolates, one pork chop isolate, and three chicken isolates. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) of the blaCMY plasmid transformants, along with a comparison to the resistance phenotypes of the original isolates, identified resistance phenotypes conferred by the plasmids (Table 1). Forty of the 41 IncI1-blaCMY plasmids only conferred resistance to drugs associated with presence of a blaCMY resistance determinant (ampicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, cefoxitin, ceftriaxone, and ceftiofur). The IncI1-blaCMY plasmid identified in isolate B095270 also conferred resistance to kanamycin. In contrast, all of the IncA/C-blaCMY plasmids conferred multi-drug resistance (MDR), defined as resistance to at least one antimicrobial in three or more antimicrobial classes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2009). The most common additional resistance conferred by the IncA/C plasmids was resistance to sulfisoxazole and tetracycline (Table 1). Resistance to chloramphenicol, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, gentamicin, and kanamycin was less common.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the blaCMY-positive Heidelberg isolates and associated blaCMY plasmids from humans, retail meat, and animals in 2009.

| Original isolate | Transformed DH10B (blaCMY-plasmid) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolate | Source | State/regiona | Additional resistanceb | Inc type | ST | Additional resistancec |

| AM38538 | human | CA | - | I1 | 2 | - |

| AM38653 | human | CA | - | I1 | 12 | - |

| AM39099 | human | CA | KAN STR TET | I1 | 12 | - |

| AM39223 | human | MO | CHL FIS KAN STR SXT TET | A/C | NA | CHL FIS KAN SXT TET |

| AM39617 | human | CA | GEN FIS KAN STR TET | A/C | NA | FIS TET |

| AM39619 | human | CA | - | I1 | 66 | - |

| AM39623 | human | CA | KAN TET | I1 | 66 | - |

| AM39638 | human | OR | KAN STR TET | I1 | 12 | - |

| AM40136 | human | CA | GEN(I) STR TET | I1 | 12 | - |

| AM40276 | human | CA | KAN STR TET | I1 | 66 | - |

| AM40553 | human | TX | KAN TET | I1 | 66 | - |

| AM40864 | human | LX | KAN STR TET | I1 | 12 | - |

| AM41042 | human | WA | - | I1 | 12 | - |

| AM41045 | human | WA | - | I1 | 12 | - |

| AM41063 | human | WA | KAN TET | I1 | 66 | - |

| AM41520 | human | SC | - | I1 | 12 | - |

| AM41677 | human | NY | - | I1 | 12 | - |

| AM42361 | human | NC | KAN STR TET | I1 | 12 | - |

| N19970 | chicken breast | CA | - | I1 | 12 | - |

| N23584 | chicken breast | OR | - | I1 | 12 | - |

| N23585 | chicken breast | OR | - | I1 | 12 | - |

| N23600 | chicken breast | OR | - | I1 | 12 | - |

| N20011 | chicken breast | CO | - | I1 | 65 | - |

| N23586 | chicken breast | OR | - | I1 | 12 | - |

| N20018 | chicken breast | CO | - | I1 | ND | - |

| N20244 | chicken breast | NM | - | I1 | 12 | - |

| N20019 | chicken breast | CO | - | I1 | 66 | - |

| N20020 | chicken breast | CO | - | I1 | 66 | - |

| N19997 | pork chop | CA | KAN FIS STR SXT TET | A/C | NA | FIS SXT |

| N20030 | chicken breast | CO | KAN STR TET | I1 | 66 | - |

| N19986 | chicken breast | CA | KAN STR TET | I1 | 66 | - |

| N19994 | chicken breast | CA | KAN STR TET | I1 | 66 | - |

| N19960 | chicken breast | CA | KAN STR TET | I1 | 23 | - |

| N20025 | ground turkey | CO | - | I1 | 12 | - |

| B094285 | chicken | 5 | - | I1 | 12 | - |

| B094322 | chicken | 3 | CHL FIS GEN KAN STR TET | A/C | NA | CHL FIS GEN(I) KAN(I) TET |

| B094329 | chicken | 5 | KAN STR TET | I1 | 12 | - |

| B094330 | chicken | 2 | KAN STR TET | I1 | 12 | - |

| B094338 | chicken | 5 | - | I1 | 12 | - |

| B094351 | chicken | 3 | CHL FIS GEN KAN STR | A/C | NA | CHL(I) FIS GEN(I) KAN(I) |

| B094559 | chicken | 3 | CHL FIS GEN KAN STR TET | A/C | NA | CHL FIS GEN(I) KAN(I) TET |

| B095017 | turkey | 3 | KAN STR TET | I1 | 12 | - |

| B094705 | chicken | 2 | - | I1 | 12 | - |

| B095082 | chicken | 5 | - | I1 | 12 | - |

| B094798 | chicken | 2 | - | I1 | 12 | - |

| B095265 | chicken | ND | - | I1 | 12 | - |

| B095270 | chicken | 1 | KAN | I1 | 12 | KAN |

State of isolation is given for human and retail meat sampling, whereas region where isolate was obtained is given for sampling of food animals at slaughter. Region 1 includes ME, VT, NH, NY, MA, CT, RI, PA, MD, DE, NJ, OH, IN, MI, DC; region 2 includes VA, KY, TN, NC, SC, GA, AL, WV, FL, Puerto Rico; region 3 includes ND, SD, NE, KS, MN, IA, MO, WI, IL; region 4 includes OK, AR, LA, TX, MS; region 5 includes WA, MT, OR, ID, WY, CO, UT, NM, AZ, NV, CA, AK; region 6 includes Hawaii, Guam, U.S. Virgin Islands, Mariana Islands, and American Samoa

All isolates were resistant to ampicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, cefoxitin, and ceftiofur.

All transformants were resistant to ampicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, cefoxitin, and ceftiofur. Additionally, all transformants were resistant to streptomycin due to the natural resistance of DH10B cells.

CHL, chloramphenicol; FIS, sulfisoxazole; GEN, gentamicin; KAN, kanamycin; SXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; TET, tetracycline; (I), intermediate Additional drugs tested: AMI, amikacin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; NAL, nalidixic acid Inc type, incompatibility/replicon type; ST, sequence type; -, none; NA, not applicable; ND, not determined

IncI1 plasmids were compared using plasmid multi-sequence typing (pMLST) (Garcia-Fernandez, Chiaretto et al. 2008). Currently, IncA/C plasmids are not included in the pMLST scheme. Of the 41 IncI1 plasmids, 27 (65.8%) were ST12 (Table 2). Ten plasmids had a new ST profile, ST66; however, since this profile differed from ST12 by only one allele (trbA), it is considered to be part of the ST12 clonal complex. We also identified a single ST2, ST23, ST65 (a new profile), and one plasmid that could not be typed due to a large insertion in the trbA allele.

Table 2. Plasmid multi-locus sequence type of the Heidelberg IncI1-blaCMY plasmids.

| Allele | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid | Source | ardA | pilL | repI | sogS | trbA | ST | Clonal Complex |

| pAM38538 | Human | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | |

| pAM38653 | Human | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

| pAM39099 | Human | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

| pAM39619 | Human | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 11 | 66 | CC-12 |

| pAM39623 | Human | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 11 | 66 | CC-12 |

| pAM39638 | Human | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

| pAM40136 | Human | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

| pAM40276 | Human | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 11 | 66 | CC-12 |

| pAM40553 | Human | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 11 | 66 | CC-12 |

| pAM40864 | Human | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

| pAM41042 | Human | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

| pAM41045 | Human | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

| pAM41063 | Human | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 11 | 66 | CC-12 |

| pAM41520 | Human | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

| pAM41677 | Human | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

| pAM42361 | Human | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

| pN19970 | Chicken breast | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

| pN23584 | Chicken breast | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

| pN23585 | Chicken breast | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

| pN23600 | Chicken breast | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

| pN20011 | Chicken breast | 4 | 3 | 1 | 10 | 18 | 65 | |

| pN23586 | Chicken breast | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

| pN20018 | Chicken breast | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ND | ND | |

| pN20244 | Chicken breast | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

| pN20019 | Chicken breast | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 11 | 66 | CC-12 |

| pN20020 | Chicken breast | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 11 | 66 | CC-12 |

| pN20030 | Chicken breast | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

| pN19986 | Chicken breast | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 11 | 66 | CC-12 |

| pN19994 | Chicken breast | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 11 | 66 | CC-12 |

| pN19960 | Chicken breast | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 11 | 66 | CC-12 |

| pN20025 | Ground turkey | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 23 | |

| pB094285 | Chicken | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

| pB094329 | Chicken | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

| pB094330 | Chicken | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

| pB094338 | Chicken | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

| pB095017 | Turkey | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

| pB094705 | Chicken | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

| pB095082 | Chicken | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

| pB094798 | Chicken | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

| pB095265 | Chicken | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

| pB095270 | Chicken | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 12 | CC-12 |

ST, sequence type

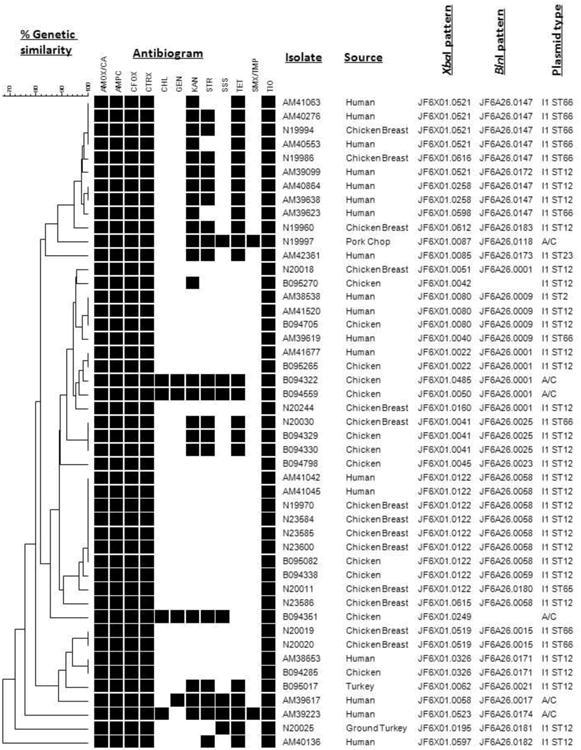

Determining similarity by PFGE of the blaCMY-positive isolates

Two-enzyme PFGE was used to evaluate the genetic relatedness of ESC-resistant strains from different sources (Figure 1). Twenty-seven patterns were generated for the 47 isolates, indicating the dissemination of multiple distinct isolate types. Four groups containing three or more indistinguishable PulseNet PFGE patterns were identified; VetNet patterns matched those found in PulseNet. The largest group contained seven isolates (JF6X01.122/JF6A26.0058) including a single chicken isolate and isolates from chicken breasts and humans. While most of the animal/retail meat isolates were recovered from chicken or chicken breasts, one isolate each was recovered from pork chop, ground turkey, and a turkey that grouped separately from chickens and chicken breast isolates (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PFGE patterns of blaCMY-positive Salmonella enterica ser. Heidelberg isolated from food animals, retail meat, and humans from the United States in 2009. Dendrogram of percent genetic similarity by PFGE was generated using BioNumerics based on XbaI and BlnI restriction digestion. Pattern analysis and UPGMA dendrogram generation were performed using BioNumerics software (Applied Maths, Saint-Martens-Latem, Belgium) with the Dice coefficient and tolerance of 1.5%. Percent similarity is located above dendrogram. Antibiogram displays the antimicrobial resistance profile of the isolates; a black box indicates resistance to that antimicrobial. Isolate number, source, XbaI pattern name, BlnI pattern name, plasmid incompatibility type, and sequence type (where applicable) are listed to the right of the antibiogram. The BlnI patterns for isolate B095270 and B094351 have not been identified previously by PulseNet so do not have pattern names at this time.

Discussion

In the last decade, the rise in ESC- resistant Salmonella ser. Heidelberg in the United States has been documented, but the recent sharp increase in resistance among retail meat, food animal, and human isolates is especially concerning (United States Food and Drug Administration (B) 2009; Folster, Pecic et al. 2010). Taken together with studies documenting the invasiveness and antimicrobial resistance observed among isolates of serotype Heidelberg, it is imperative to understand the factors driving this phenomenon and determine what actions may mitigate its impact in the future (Crump, Medalla et al. 2011).

In this study, we examined 47 CMY-β-lactamase producing Heidelberg isolated in 2009 from retail meat, food animals, and humans and characterized their blaCMY plasmids. PFGE analysis identified five clusters with indistinguishable patterns for isolates recovered from both human clinical cases and chicken carcasses/chicken breasts. The largest group contained seven isolates with XbaI PulseNet pattern JF6X01.0122 (VetNet pattern JF6X01.0001 ARS), one of the more common Heidelberg patterns in PulseNet and VetNet. Most of the isolates could be distinguished by their XbaI pattern (27 different XbaI patterns among 47 isolates). This suggests that the rise in ESC resistant Heidelberg in human and food animal sources is not due to a single clone expansion, but is likely due to multiple independent events of ESC resistance acquisition in a serovar associated with poultry, where cephalosporins are used (Silvers 2002). This observation is consistent with what has been observed in retail meat isolates of Heidelberg from 2004-2009 (United States Food and Drug Administration (A) 2009).

All of the blaCMY genes were located on plasmids, which mediate nearly all ESC resistance in Salmonella in the U.S. Most plasmids (41/47) were replicon type IncI1, a common blaCMY-encoding plasmid type along with IncF, IncHI1, and IncA/C (Hopkins, Liebana et al. 2006; Baudry, Mataseje et al. 2009; Fricke, McDermott et al. 2009; Folster, Pecic et al. 2010). All of the IncI1 plasmids except one conferred only blaCMY associated resistance. Plasmid pB095270 also conferred kanamycin resistance, which is the first IncI1-blaCMY plasmid we identified that conferred an additional resistance phenotype (Folster, Pecic et al. 2010; Folster, Pecic et al. 2011). IncI1-blaCMY plasmids are common among poultry associated Salmonella serotypes and Escherichia coli from various agricultural and clinical sources (Baudry, Mataseje et al. 2009). IncI1 plasmids are usually highly mobile and are characterized by the presence of a type IV pilus locus, which may be involved in conjugation and virulence, and have been shown to be more common among pathogenic rather than commensal E. coli (Kim and Komano 1997; Johnson, Wannemuehler et al. 2007). The six remaining plasmids were IncA/C, a MDR-plasmid ubiquitous in agricultural settings (Lindsey, Fedorka-Cray et al. 2009; Mulvey, Susky et al. 2009).

Subtyping using pMLST revealed that most IncI1 plasmids in this study were sequence type 12, consistent with earlier observations (Folster, Pecic et al. 2010; Folster, Pecic et al. 2011). The pMLST database (Jolley and Maiden 2010) also documents additional ST12 IncI1 plasmids, including a blaCMY-2 positive Salmonella Kentucky isolate from poultry (Fricke, McDermott et al. 2009) and blaCMY-2 plasmids from Salmonella and E. coli isolated from human, animal, and environmental sources in Canada (Fricke, McDermott et al. 2009; Mataseje, Baudry et al. 2010).

Interestingly, ten of the plasmids we characterized in this study were ST66, a novel sequence type differing from ST12 by a single allelic change (trbA3 to trbA11) (Table 2). Since five out of six alleles match, ST66 is thought to be related to ST12 and has been placed in the same clonal complex (CC) as ST12, CC12. When we examined the source and state/region of the isolates with the ST66 plasmid, all ten isolates were from chicken breasts or humans, and nine out of ten isolates were obtained in western states (California, Colorado, and Washington). These were collected over a five month period suggesting that they were not due to a single outbreak. None of the animal isolates obtained at slaughter, including those from region 5 (western states), contained the ST66 IncI1 plasmid. Additional studies are needed to explain this phenomenon. However, due to our limited number of Heidelberg isolates from animals, it's also possible that we simply missed the ST66 plasmids among this source.

Among the IncI1-blaCMY plasmids we also identified a ST2, ST23, ST65, and a nontypeable plasmid. Previously identified ST2 IncI1 plasmids include blaCMY-2 positive isolates of S. Heidelberg, S. Typhimurium, and E. coli found in humans, dogs, and environmental sources (Garcia-Fernandez, Chiaretto et al. 2008; Mataseje, Baudry et al. 2010). ST23 IncI1 plasmids have been identified in blaCMY-2 positive isolates of S. Heidelberg and E. coli from humans (Mataseje, Baudry et al. 2010). ST65 is a new sequence type and the unidentifiable plasmid had a large insertion into the trbA allele that prevented it from being typed, although the remaining four alleles matched ST12 and ST66, suggesting that it may be related to these sequence types. Further sequencing and categorization are necessary to fully understand the diversity of plasmids that carry ESC and other relevant antimicrobial resistance.

Conclusions

Overall, this work demonstrates that the 2009 increase in ESC resistance among Salmonella Heidelberg in the United States was due to the dissemination of blaCMY on IncI1 and IncA/C plasmids in a variety of genetic backgrounds, and likely not the result of clonal expansion. The IncI1 plasmids showed identical STs in strains from humans, chicken carcasses, and chicken breasts, further supporting chicken products as an important source of human infection with ESC-resistant Salmonella Heidelberg. Both resistant and susceptible strains of Salmonella Heidelberg continue to present a significant public health burden in the U.S. and elsewhere. Ongoing monitoring of human clinical cases, resistances associated with the food supply, and the characterization of plasmids from different sources will help attribute distinct resistances to different food animal sources, and will help facilitate a more global understanding of the genetics and ecology of antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella Heidelberg.

Acknowledgments

We thank the NARMS participating public health laboratories for submitting the isolates, Anne Whitney for DNA sequencing, Alessandra Carattoli for the plasmid incompatibility typing control strains, and Maria Karlsson for her critical review. This work was partially supported by an interagency agreement between CDC, USDA, and the FDA Center for Veterinary Medicine.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC, FDA or USDA.

References

- Baudry PJ, Mataseje L, et al. Characterization of plasmids encoding CMY-2 AmpC beta-lactamases from Escherichia coli in Canadian intensive care units. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;65(4):379–383. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carattoli A, Bertini A, et al. Identification of plasmids by PCR-based replicon typing. J Microbiol Methods. 2005;63(3):219–228. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carattoli A, Tosini F, et al. Characterization of plasmids carrying CMY-2 from expanded-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Salmonella strains isolated in the United States between 1996 and 1998. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46(5):1269–1272. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.5.1269-1272.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System for Enteric Bacteria (NARMS): Enteric Bacteria Annual Report 2009 [Google Scholar]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twenty-first Informational Supplement CLSI Document M100-S21. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Crump JA, Medalla FM, et al. Antimicrobial resistance among invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella enterica isolates in the United States: National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System, 1996 to 2007. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(3):1148–1154. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01333-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne EF, Fey PD, et al. Emergence of domestically acquired ceftriaxone-resistant Salmonella infections associated with AmpC beta-lactamase. JAMA. 2000;284(24):3151–3156. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.24.3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folster JP, Pecic G, et al. Characterization of extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg isolated from humans in the United States. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2010;7(2):181–187. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2009.0376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folster JP, Pecic G, et al. Characterization of bla(CMY)-Encoding Plasmids Among Salmonella Isolated in the United States in 2007. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2011 doi: 10.1089/fpd.2011.0944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe CT, Ernst ME. Do fluoroquinolones commonly cause arthropathy in children? CJEM. 2007;9(6):459–462. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500015517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricke WF, McDermott PF, et al. Antimicrobial resistance-conferring plasmids with similarity to virulence plasmids from avian pathogenic Escherichia coli strains in Salmonella enterica serovar Kentucky isolates from poultry. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75(18):5963–5971. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00786-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye JG, Fedorka-Cray PJ, et al. Analysis of Salmonella enterica with reduced susceptibility to the third-generation cephalosporin ceftriaxone isolated from U.S. cattle during 2000-2004. Microb Drug Resist. 2008;14(4):251–258. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2008.0844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Fernandez A, Chiaretto G, et al. Multilocus sequence typing of IncI1 plasmids carrying extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in Escherichia coli and Salmonella of human and animal origin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61(6):1229–1233. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins KL, Liebana E, et al. Replicon typing of plasmids carrying CTX-M or CMY beta-lactamases circulating among Salmonella and Escherichia coli isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50(9):3203–3206. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00149-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson CR, Fedorka-Cray PJ, et al. Introduction to United States Department of Agriculture VetNet: status of Salmonella and Campylobacter databases from 2004 through 2005. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2007;4(2):241–248. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2006.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TJ, Wannemuehler YM, et al. Plasmid replicon typing of commensal and pathogenic Escherichia coli isolates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(6):1976–1983. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02171-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolley KA, Maiden MC. BIGSdb: Scalable analysis of bacterial genome variation at the population level. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:595. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SR, Komano T. The plasmid R64 thin pilus identified as a type IV pilus. J Bacteriol. 1997;179(11):3594–3603. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.11.3594-3603.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey RL, Fedorka-Cray PJ, et al. Inc A/C plasmids are prevalent in multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica isolates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75(7):1908–1915. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02228-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mataseje LF, Baudry PJ, et al. Comparison of CMY-2 plasmids isolated from human, animal, and environmental Escherichia coli and Salmonella spp. from Canada. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;67(4):387–391. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey MR, Susky E, et al. Similar cefoxitin-resistance plasmids circulating in Escherichia coli from human and animal sources. Vet Microbiol. 2009;134(3-4):279–287. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippon A, Arlet G, et al. Plasmid-determined AmpC-type beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46(1):1–11. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.1.1-11.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribot EM, Fair MA, et al. Standardization of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocols for the subtyping of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella, and Shigella for PulseNet. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2006;3(1):59–67. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2006.3.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scallan E, R H, Angulo FJ, Tauxe RV, Widdowson MA, Roy SL, et al. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States—major pathogens. Emerging Infectious Disease [serial on the internet. 2011 doi: 10.3201/eid1701.P11101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvers LE, Spires CD. Use of Antimicrobials in Hatcheries: A Field Assignment. FDA Veterinarian Newsletter. 2002 January/February 2002 Volume XVII, No 1 from http://www.fda.gov/AnimalVeterinary/NewsEvents/FDAVeterinarianNewsletter/ucm106872.htm.

- Sjolund-Karlsson M, Rickert R, et al. Salmonella isolates with decreased susceptibility to extended-spectrum cephalosporins in the United States. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2010;7(12):1503–1509. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2010.0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture. National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System for Enteric Bacteria (NARMS): Animal Arm Annual Report. Washington DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- United States Food and Drug Administration (A) NARMS Retail Meat Annual Report. Rockville, MD: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- United States Food and Drug Administration (B) NARMS excutive report. Rockville, MD: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Welch TJ, Fricke WF, et al. Multiple antimicrobial resistance in plague: an emerging public health risk. PLoS One. 2007;2(3):e309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winokur PL, Vonstein DL, et al. Evidence for transfer of CMY-2 AmpC beta-lactamase plasmids between Escherichia coli and Salmonella isolates from food animals and humans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45(10):2716–2722. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.10.2716-2722.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S, White DG, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg isolates from retail meats, including poultry, from 2002 to 2006. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74(21):6656–6662. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01249-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]