Abstract

Background

Coxiella burnetii, an obligate intracellular organism, is the causative agent of the zoonotic disease Q fever. The seroprevalence rate for Q fever in the United States is 3.1%, suggesting a high number of infections each year. However, less than 200 cases of Q fever are reported to the CDC annually. This discrepancy is likely the result of underutilized diagnostics and a high percentage (>50%) of asymptomatic infections. The detection of C. burnetii in patient blood during the first 2–3 weeks of infection raises the possibility that the organism could be present in donated human blood. The purpose of this study was to determine if extracellular C. burnetii would be stable in blood under normal storage conditions.

Study Design and Methods

Donated human blood was separated into whole blood, leukoreduced whole blood, packed RBCs, and plasma. Each component was spiked with purified, extracellular C. burnetii strain Nine Mile Phase 1, and the viability and infectivity of the organisms were tested weekly.

Results

C. burnetii did not decrease in viability or the ability to infect cells after storage in any of the blood products, even after six weeks of storage at 1–6°C.

Conclusions

Extracellular C. burnetii can survive and remain infectious in donated blood products.

Introduction

Coxiella burnetii is a gram-negative bacterium that causes the zoonotic disease Q fever. It is considered a category B agent of bioterrorism due to its low infectious dose, transmission by inhalation, and environmental stability1. Humans typically acquire Q fever after inhalation of contaminated aerosols that are derived from the waste products of infected animals. The most common reservoirs related to human infection are sheep and goats2. The presentation of Q fever in its acute form can include fever, headache, malaise, and myalgia3. An atypical pneumonia is often seen. A small percentage (2–5%) of C. burnetii infections result in a chronic disease that is difficult to treat and can present as a life-threatening endocarditis.

Q fever has been a nationally notifiable disease in the US since 1999, with reported cases never exceeding 200 in any given year. However, a study conducted using samples from the 2003–2004 survey cycle of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey found that seroprevalence in the United States was 3.1%, suggesting that many cases of Q fever go unreported4. Reasons for under-reporting of Q fever probably include the non-specific nature of its symptoms, difficulties in diagnosis, and the possibility that more than 50% of infections may be asymptomatic in humans3.

During acute Q fever, C. burnetii can be detected by PCR in blood and serum up to 17 days after the onset of symptoms5, but the presence of C. burnetii DNA in the blood typically declines after the emergence of the antibody response. In patients with chronic Q fever it is also possible to detect C. burnetii in blood months after the initial infection6. In a screen of blood donors from the Netherlands during a large outbreak of Q fever in 2009, 3/1004 (0.3%) blood donors tested positive for C. burnetii DNA by PCR and showed an antibody response, but none of these donors reported Q fever symptoms7. Thus, it is possible for asymptomatic, C. burnetii-infected donors to introduce C. burnetii into the blood supply. However, transmission of C. burnetii by transfusion has not been documented.

The length of time that C. burnetii can remain viable and infectious in stored blood is not known. C. burnetii has the ability to form a spore-like “small cell variant” (SCV) when it is not replicating, and this SCV form of C. burnetii has been reported to be very stable in a variety of environments8. However, very little is known about the survival of C. burnetii in human blood under normal storage conditions. In this study, human blood and blood products were spiked with purified C. burnetii, and the survival of the bacteria under normal storage conditions was monitored.

Materials and Methods

Five hundred mls of blood was obtained from each of 3 healthy human donors. Blood was drawn into a leukotrap WB system CPDA-1 double blood bag unit (Pall Medical, Covina, CA). An aliquot of whole blood was removed from each unit prior to leukoreduction. The blood was then leukoreduced using the leukotrap filter of the WB system (Pall Medical, Covina, CA). After an aliquot of leukoreduced blood was taken, the leukoreduced blood was separated into packed RBCs and plasma according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Blood was obtained in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review boards of Emory University and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Aliquots (40 mls) of whole blood, leukoreduced whole blood, packed RBCs, and plasma were placed in 50 ml conical tubes and spiked with approximately 1.6 × 106 genome equivalents of purified C. burnetii strain Nine Mile Phase 1 (RSA493). Aliquots of 600 µl were taken from each sample immediately after spiking, and then the tubes were stored at 1–6°C. At days 7, 14, 22, 28, 35, and 42 the samples were gently mixed and additional 600 µl aliquots were taken.

For each time point, 10 µl of the aliquot was plated on a 100 mm plate containing ACCM-2 in 1% agarose and overlayed with ACCM-2 in 0.25% agarose. ACCM-2 was made according to published instructions9. The plates were incubated at 37°C in a tri-gas incubator (Thermo Scientific Heracell 150i, Waltham, MA), at 2.5% O2, 5% CO2, and 92.5% N2. Colonies were counted 14 days after plating. Also for each time point, 200 µl of the aliquot was introduced into a T-25 flask containing a 70% confluent monolayer of rabbit kidney (RK-13) cells. At 7 and 14 days after inoculation, 200 µl of the culture media was removed, DNA isolated using a QIAmp DNA mini kit tissue protocol (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and quantitative PCR targeting IS1111 was performed as described previously10.

Results

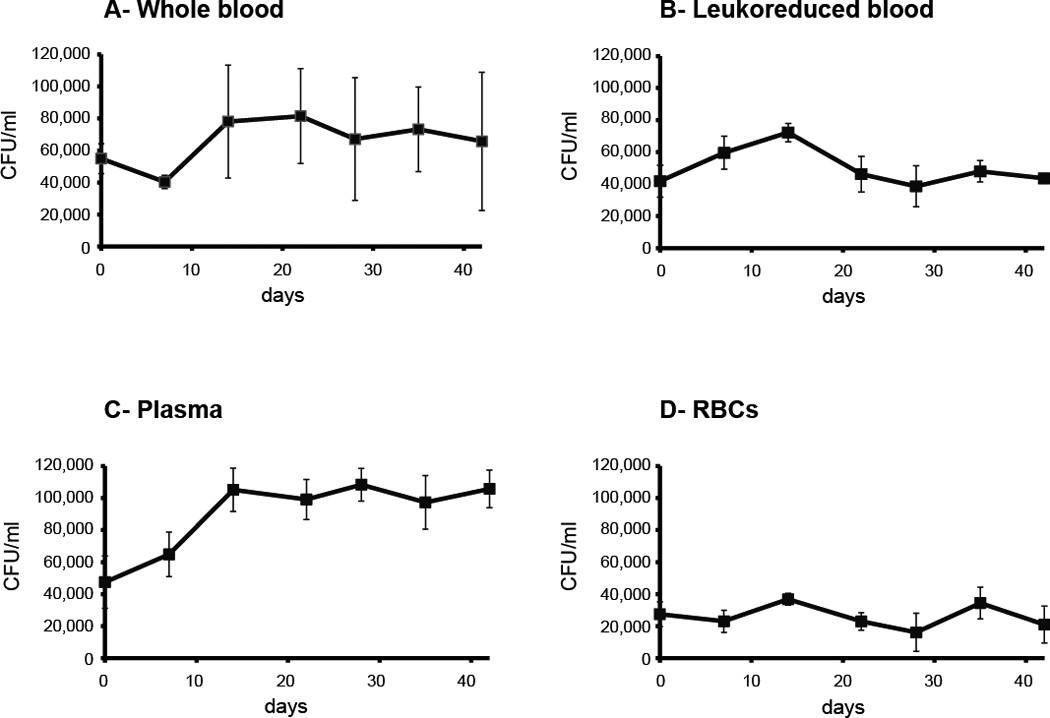

Whole blood from three random donors was separated into leukoreduced blood, RBCs, and plasma. Aliquots (40 mls) of each type of blood product were stored at 1–6°C, spiked with C. burnetii strain Nine Mile Phase 1, and samples were taken weekly for analysis. Although C. burnetii is an obligate intracellular bacterium, recent work has shown that C. burnetii can be grown on plates using a unique semisolid agarose medium and a microaerobic environment9. The colony forming units (CFU) determined by use of this growth system was employed to monitor viability of C. burnetii in the stored blood products. After separation of the components and adding C. burnetii, three of the products (whole blood, leukoreduced blood, and plasma) contained similar numbers of viable C. burnetii (Figure 1A, 1B, and 1C). The number of viable organisms in RBCs was reduced compared to the other products (Figure 1D). This difference was statistically significant when compared to each of the other three blood products (p<0.022).

Figure 1.

Viability of C. burnetii in whole blood and blood products. Donated human blood was separated into leukoreduced blood, plasma, and RBCs; spiked with viable C. burnetii, and then stored at 1–6°C. Aliquots were taken at the indicated times and the number of colony forming units (CFU) in the stored blood or blood products determined by counting colony growth on ACCM-2 agar plates.

The number of viable C. burnetii in whole blood or in specific fractionated blood products did not significantly decline during the 42 days that these products were stored and evaluated (Figure 1). The only significant change was an apparent increase in the number of viable C. burnetii in plasma by day 14. There was a statistically significant difference between the number of CFU at day 14 compared to days 0 and 7 (p<0.03). From day 14 through day 42, the number of viable C. burnetii in plasma did not significantly increase or decrease. The reason for higher numbers of bacteria in plasma at days 14–42 is not known.

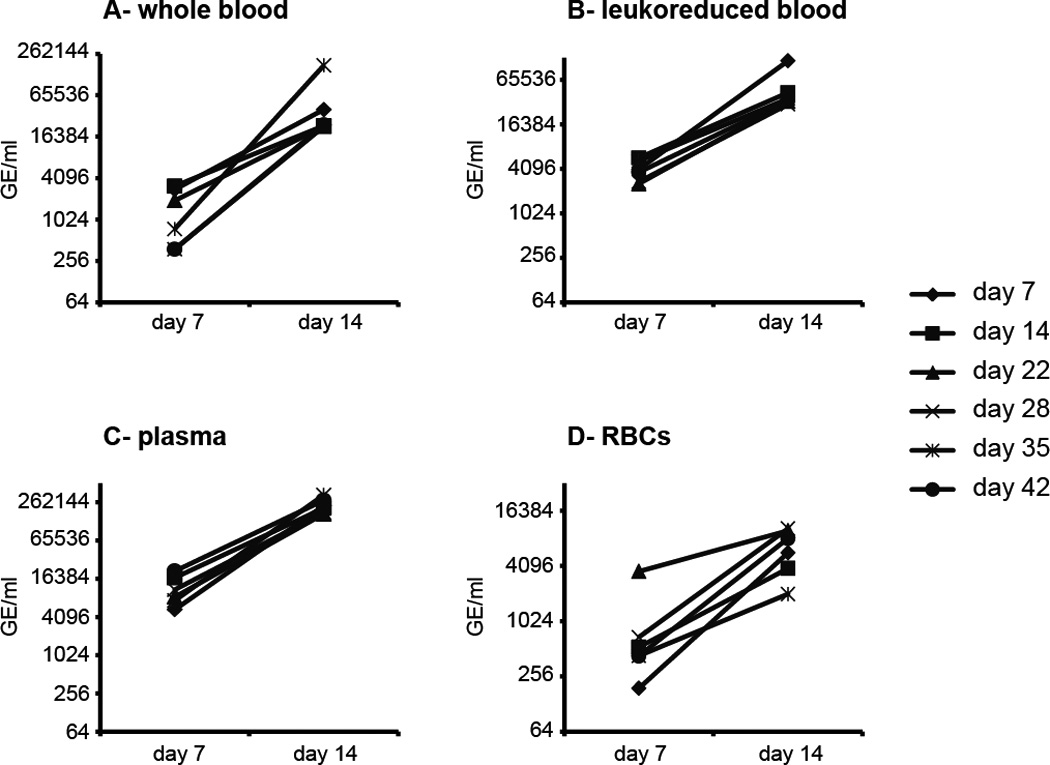

To determine if the C. burnetii in the stored blood products remained infectious, aliquots were placed on RK13 (rabbit kidney) cells and the growth of the organisms in culture was monitored by quantitative PCR. As shown in Figure 2, all of the samples were infectious in culture and demonstrated robust growth between the two sampling points (7 and 14 days after inoculation of the cultures). The most robust growth was seen in the plasma samples, most likely due to higher numbers of bacteria introduced into the cultures.

Figure 2.

C. burnetii stored in whole blood and blood products remains infectious. Donated human blood was separated into leukoreduced blood, plasma, and RBCs; spiked with viable C. burnetii, and then stored at 1–6°C. Aliquots were taken at the indicated times and used to inoculate cultures of RK13 rabbit kidney cells. At 7 and 14 days after inoculation an aliquot of the culture was analyzed by quantitative PCR targeting the C. burnetii IS1111 transposase. A higher number of genome equivalents (GE) at day 14 indicates infection of the RK13 cells and growth in culture.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that C. burnetii can retain significant viability and infectivity when kept in whole blood and blood products at 1–6°C. There was no decline in viability during 42 days of storage. Although plasma can be stored frozen for longer periods of time, blood products are not typically stored past 42 days at 1–6°C. For the CPDA-1 anticoagulant used in this study, the recommendation is to use the whole blood or leukoreduced blood product within 35 days, but a 42 day shelf life can be achieved with some additional additives. Therefore, testing out to 42 days of storage shows that C. burnetii present in a donated blood product stored at 1–6°C could maintain its ability to infect a recipient for the duration of the product’s shelf life. This suggests that blood product transfusion represents a possible means of transmitting Q fever.

For this study, C. burnetii was added to the blood products after separation, and was therefore present in the extracellular portion of each component. In human infections, C. burnetii primarily infects cells of the monocyte lineage, and can only replicate when inside a parasitophorous vacuole. However, there is evidence that a significant portion of C. burnetii is present in the extracellular compartment of human blood during infection. Early in infection, C. burnetii can readily be detected in human serum by PCR5, and in mouse experiments we have found similar numbers of C. burnetii genomes present in murine serum and whole blood during acute infection (unpublished observations). C. burnetii found in both whole blood and serum during acute infection is viable. Leukoreduction of infected blood may remove most or all of the intracellular C. burnetii, but the evidence suggests that significant numbers of organisms will remain after leukoreduction. It is difficult to test this idea directly because of the low availability of sufficient quantities of blood from acute Q fever patients. Nevertheless, the results described here demonstrate that any C. burnetii found in stored blood components will easily survive normal storage conditions.

C. burnetii exists in two morphological forms: the large cell variant (LCV) and the small cell variant (SCV). The LCV form is the replicative form and will predominate in the parasitophorous vacuole. The SCV form is considered to be spore-like, undergoes little or no replication, and has the ability to survive for extended periods under relatively harsh conditions. Extracellular C. burnetii will transition to the SCV after leaving the vacuole. It is therefore expected that the SCV form of C. burnetii will predominate in leukoreduced blood, plasma, or RBCs. C. burnetii in whole blood likely be a mixture of LCV and SCV and could convert to the SCV form during storage. Thus, the extended survival attributes of the SCV would be quite relevant for survival of C. burnetii in blood products.

Although the stability of C. burnetii was very similar among the different blood products, there were distinct differences in the growth and yield of organisms among the products. Immediately after spiking, the number of CFU in plasma was similar to whole blood and leukoreduced blood, but the number of CFU in plasma increased at day 7 and day 14. The possibility exists that there was some cell-free growth of C. burnetii in plasma, however it is more likely that whole blood contains inhibitors of C. burnetii colony formation that were removed in the plasma. These inhibitors may be present in RBCs, as fewer CFU were recovered from RBCs at all time points compared to the other products. Interestingly, the inhibition of growth imparted by RBCs was even observed after RBC-stored C. burnetii was inoculated onto RK13 cultures (Figure 2). The source of this inhibition warrants further study.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the CDC or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

All of the authors report no conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Madariaga MG, Rezai K, Trenholme GM, Weinstein RA. Q fever: a biological weapon in your backyard. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3:709–721. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(03)00804-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McQuiston JH, Childs JE. Q fever in humans and animals in the United States. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2002;2:179–191. doi: 10.1089/15303660260613747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maurin M, Raoult D. Q fever. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:518–553. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.4.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson AD, Kruszon-Moran D, Loftis AD, McQuillan G, Nicholson WL, Priestley RA, Candee AJ, Patterson NE, Massung RF. Seroprevalence of Q fever in the United States, 2003–2004. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81:691–694. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2009.09-0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schneeberger PM, Hermans MH, van Hannen EJ, Schellekens JJ, Leenders AC, Wever PC. Real-time PCR with serum samples is indispensable for early diagnosis of acute Q fever. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2010;17:286–290. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00454-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Hoek W, Versteeg B, Meekelenkamp JC, Renders NH, Leenders AC, Weers-Pothoff I, Hermans MH, Zaaijer HL, Wever PC, Schneeberger PM. Follow-up of 686 patients with acute Q fever and detection of chronic infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:1431–1436. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hogema BM, Slot E, Molier M, Schneeberger PM, Hermans MH, van Hannen EJ, van der Hoek W, Cuijpers HT, Zaaijer HL. Coxiella burnetii infection among blood donors during the 2009 Q-fever outbreak in The Netherlands. Transfusion. 2012;52:144–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coleman SA, Fischer ER, Howe D, Mead DJ, Heinzen RA. Temporal analysis of Coxiella burnetii morphological differentiation. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:7344–7352. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.21.7344-7352.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Omsland A, Beare PA, Hill J, Cockrell DC, Howe D, Hansen B, Samuel JE, Heinzen RA. Isolation from animal tissue and genetic transformation of Coxiella burnetii are facilitated by an improved axenic growth medium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:3720–3725. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02826-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loftis AD, Reeves WK, Szumlas DE, Abbassy MM, Helmy IM, Moriarity JR, Dasch GA. Rickettsial agents in Egyptian ticks collected from domestic animals. Exp Appl Acarol. 2006;40:67–81. doi: 10.1007/s10493-006-9025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]