Abstract

A non-viral gene delivery nanovehicle based on Alkyl-PEI2k capped MnO nanoclusters was synthesized via a simple, facile method and used for efficient siRNA delivery and magnetic resonance imaging.

Inorganic nanoparticles (NPs) have shown great potential for molecular imaging and gene/drug delivery.1 Compared with other transfection methods, inorganic NP based nanocarriers have their own advantages: (1) high aspect ratio and tailorable surface for effective modification and gene binding;2 (2) biocompatible and can easily penetrate cell membrane which are must for efficient gene delivery;3 (3) can be used as imaging agents for gene tracking.4 Manganese oxide nanoparticles (MONPs) which can shorten the longitudinal (or spin-lattice) relaxation time have emerged as potential T1 contrast agents for MRI.5Very recently, the Park group6 reported polyethylenimine 25 kDa (PEI25k) coated hollow MONPs for efficient vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) siRNA delivery. PEI25k indeed has been reported as an efficient siRNA binding polymer for siRNA delivery, however, it also has shown certain cytotoxic effects (e.g., cell death, apoptosis and inhibition of cell differentiation).7–9 Previously, we reported alkylation modified PEI2k (N-Alkyl-PEI2k) capped superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) nanoparticles for siRNA delivery and T2 MRI tracking, which showed much less toxicity than that of PEI25k.10,11 However, SPIO based negative contrast agents are suboptimal for imaging when hemorrhages in tissues are present, such as in hemorrhagic transformed ischemic stroke, tumors, or cell injection locations.12–15

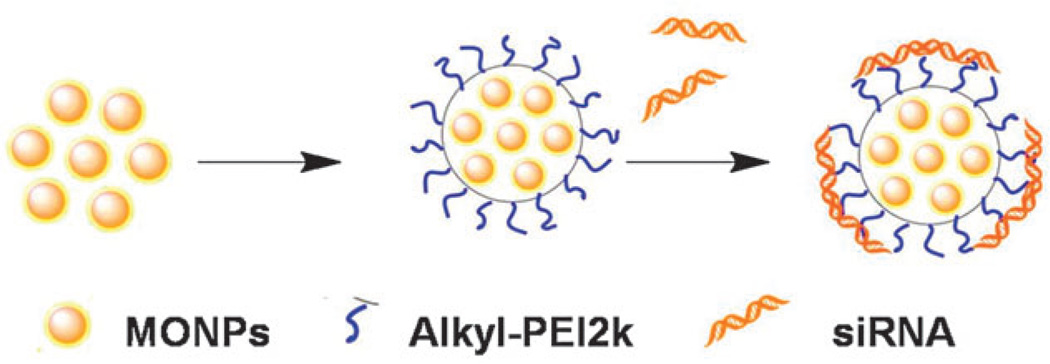

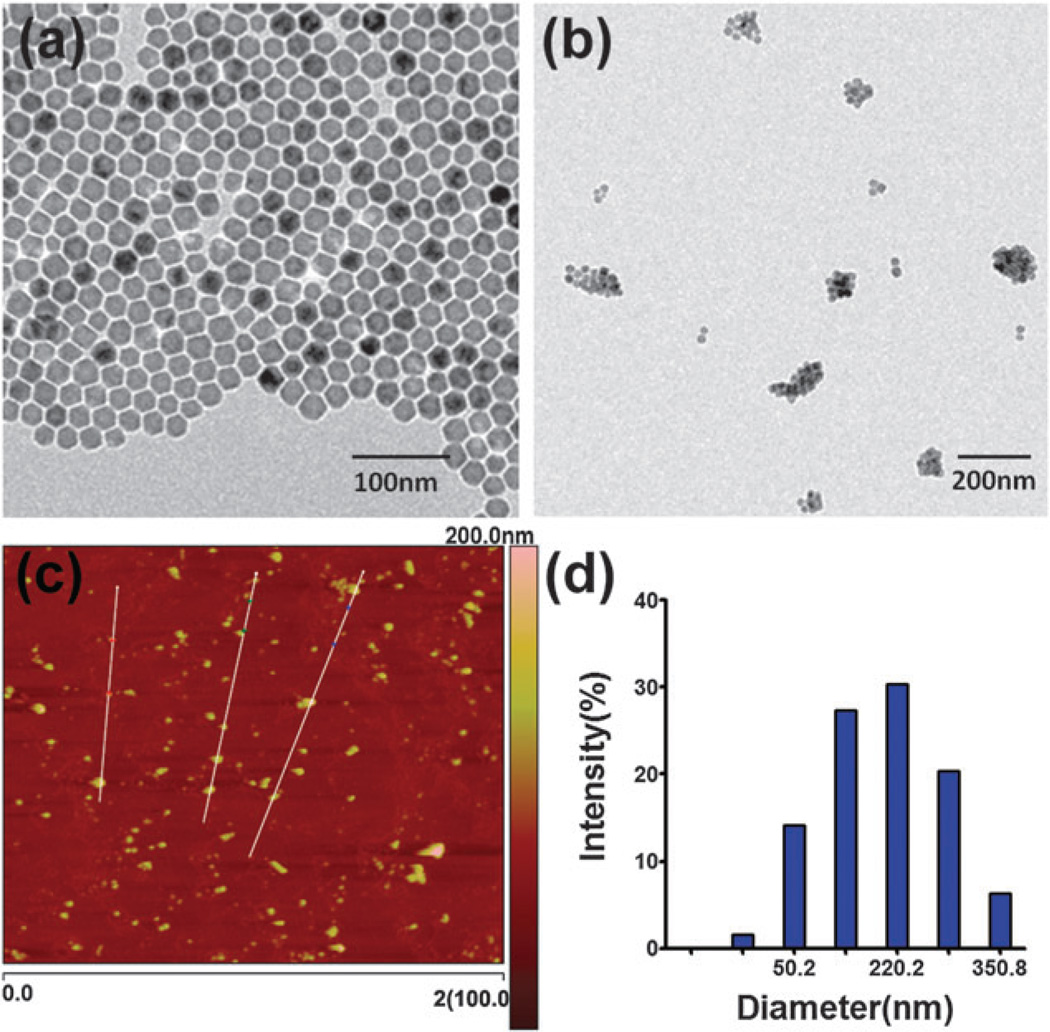

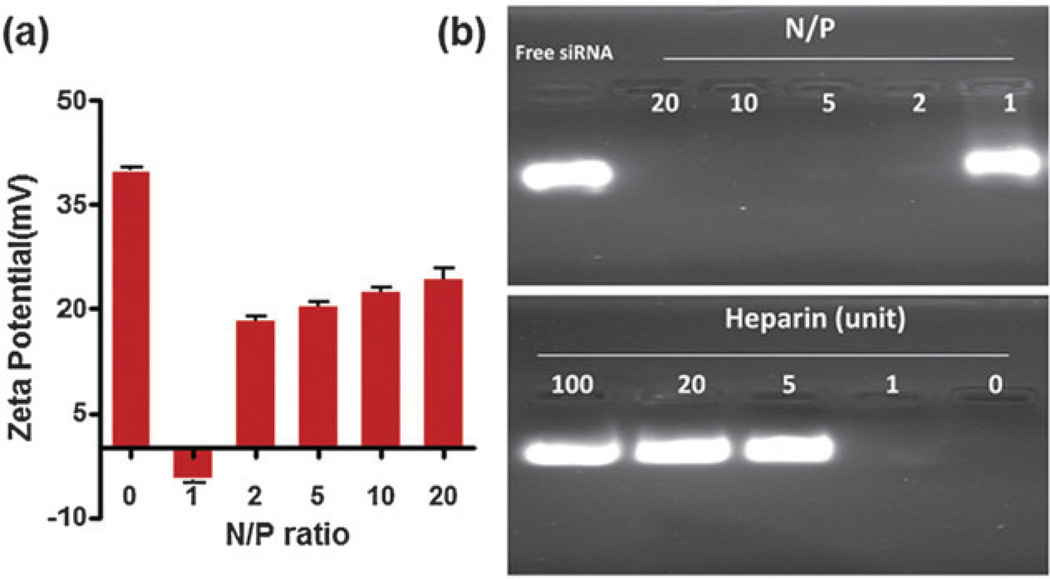

Here we report a novel MONP-based nanocarrier by using low molecular weight amphiphilic Alkyl-PEI2k to synthesize nanoclusters with MONPs (Alkyl-PEI2k-MnOs) (Fig. 1). Our results showed that such nanocarriers can effectively bind and deliver firefly luciferase (fluc) siRNA into 4T1-fluc cells and can be tracked by T1-weighted MRI. In this study, we used a facile strategy to prepare Alkyl-PEI2k-MnOs which was slightly modified from our previously reported procedure for iron oxide modifications.10 Briefly, 25 nm MnO nanoparticles (MONPs) in hexane16 were dried under argon and redispersed in chloroform together with Alkyl-PEI2k. Then, the mixed solution was added slowly into water with sonication. The mixture was under shaking for overnight and the remaining chloroform was removed through rotary evaporation. Fig. 2a shows the 25 nm hydrophobic MnO nanoparticles. The TEM image of the Alkyl-PEI2k-MnOs nanoclusters dispersed in water is shown in Fig. 2b with an average core size of the nanoclusters nearly 120 nm. The overall topographic analysis of the MONPs using AFM showed the average height and length of the clusters to be 150.6 nm and 197.4 nm, respectively (Fig. 2c). The larger diameter of the Alkyl-PEI2k-MnOs determined by AFM may be caused by the AFM tip broadening effect and particle-flattening on the mica surface. Due to the Alkyl-PEI2k polymer coating, the hydrodynamic size of clusters measured by DLS was about 220.2 ± 3.47 nm (Fig. 2d). Consequently, the thickness of Alkyl-PEI2k onto the nanocluster could be about 50 nm. Due to the presence of amine groups on the alkylated PEI2k coating, as expected, zeta potential of the Alkyl-PEI2k-MnO nanoclusters is positively charged (40.07 ± 0.55 mV, Fig. 3a).

Fig. 1.

Synthetic scheme for the formation of Alkyl-PEI2k-MnO/siRNA nanoclusters.

Fig. 2.

TEM images of the 25 nm MONPs dispersed in hexane (a), and Alkyl-PEI2k-MnO nanoclusters dispersed in water (b); (c) AFM image of the Alkyl-PEI2k-MnO nanoclusters; (d) hydrodynamic size of the Alkyl-PEI2k-MnO nanoclusters monitored by DLS.

Fig. 3.

(a) Zeta potential of the Alkyl-PEI2k-MnOs/siRNA at different N/P ratios. (b) Agarose gel electrophoresis and heparin decomplexation assay of the Alkyl-PEI2k-MnO/siRNA complex.

The most attractive feature of the alkylation modified PEI2k for siRNA binding could be attributed to the electrostatic interactions between the amine groups of the polymer and phosphate groups of siRNAs which eventually help form polyelectrolyte complexes.17 Thus, to evaluate the siRNA binding ability of Alkyl-PEI2k-MnOs, we mixed the particles with fluc siRNA at varying nitrogen/phosphate (N/P) ratios (N/P ratio from 1 to 20) and conducted the agarose gel electrophoresis and heparin decomplexation assay. As shown in Fig. 3b, the migration of siRNA was completely retarded by the Alkyl-PEI2k-MnOs when N/P ratios are higher than 2, however, when heparin was added, siRNA was released from the complexes, indicating that lucsiRNA can successfully bind to the surface of Alkyl-PEI2k-MnOs. Efficient complexation at a low N/P ratio also suggested the strong binding ability of the Alkyl-PEI2k-MnOs to siRNA. Meanwhile, as surrounded by the negatively charged lucsiRNA, zeta potential of the Alkyl-PEI2k-MnOs/siRNA complexes at different N/P ratios also decreased accordingly (Fig. 3a). At an N/P ratio of 1, the zeta potential dropped to −4.64 ± 0.68 mV.

One motive to develop effective gene transfection methods is the inability of siRNA to adsorb and penetrate the negatively charged cell membrane.18 To examine the cellular uptake behavior of our new siRNA delivery vehicle, we carried out fluorescence microscope imaging of 4T1-fluc cells after being treated with Cy3-labeled lucsiRNA. Comparison of the free lucsiRNA, Lipofectamine™ 2000 and Alkyl-PEI2k-MnO/siRNA (Fig. S1, ESI†) revealed that the Alkyl-PEI2k-MnO/siRNA complex group emits much stronger fluorescent signals than those of the free lucsiRNA and Lipofectamine™ 2000 groups. Additional confocal microscopic images of 4T1-fluc cells in the presence of Lipofectamine™ 2000/siRNA and Alkyl-PEI2k-MnO/siRNA (Fig. S2, ESI†) further confirmed that more siRNA can be delivered into cells by using our new siRNA delivery vehicle compared to Lipofectamine™ 2000.

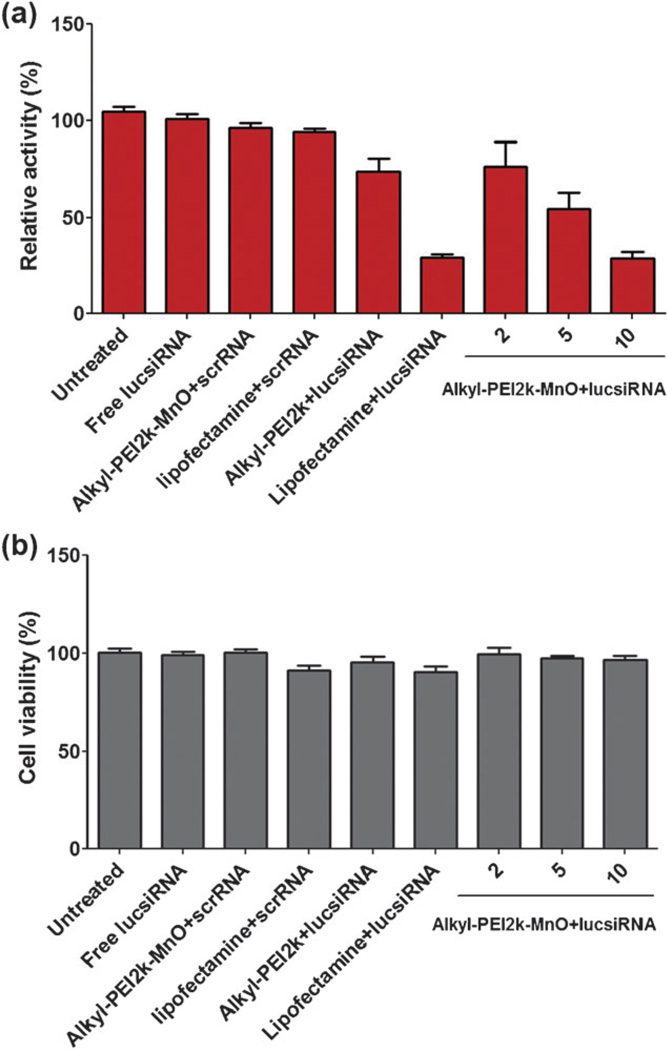

As the Alkyl-PEI2k-MnO/siRNA complexes can be successfully internalized by 4T1-fluc cells, it is expected that the flucsiRNA can be delivered and released into the cells and eventually cause gene-silencing. To confirm this, we measured the bioluminescence imaging (BLI) signal intensity of the transfected 4T1-fluc cells after conducting several control studies. From Fig. 4a we found that, compared to the untreated group, both the Lipofectamine™ 2000 and Alkyl-PEI2k-MnO/siRNA groups at an N/P ratio of 10 showed a great decrease of BLI signal intensity, suggesting a higher transfection rate. As expected, neither the scrambled siRNA (scrRNA) nor free lucsiRNA showed any significant decrease of the BLI signal intensity. However, the Alkyl-PEI2k (at an N/P ratio of 10) group showed somewhat reduced gene expression. This further confirmed that both Alkyl-PEI2k and MONPs can have an effect on transferring siRNA into cells. It is well known that PEI (polyethylenimine) is highly efficient for siRNA delivery due to the cationic surface.19,20 Additionally, it has been reported that physically stable siRNA complexes with size above 100 nm are more easily internalized into cells by the endocytic pathway than the smaller ones.21 To test the cytotoxicity of the Alkyl-PEI2k-MnOs, we conducted an MTT study. Results shown in Fig. 4b indicated that the toxicity of the Alkyl-PEI2k-MnOs is very low compared to the other control groups even at the highest N/P ratio.

Fig. 4.

(a) Bioluminescence imaging (BLI) signal intensity of the transfected 4T1-fluc cells after being exposed to Alkyl-PEI2k-MnO/siRNA (siRNA = 6 pmol) complexes at different N/P ratios. (b) Cytotoxic effect of Alkyl-PEI2k-MnO/siRNA (siRNA = 6 pmol) complexes on 4T1-fluc cells.

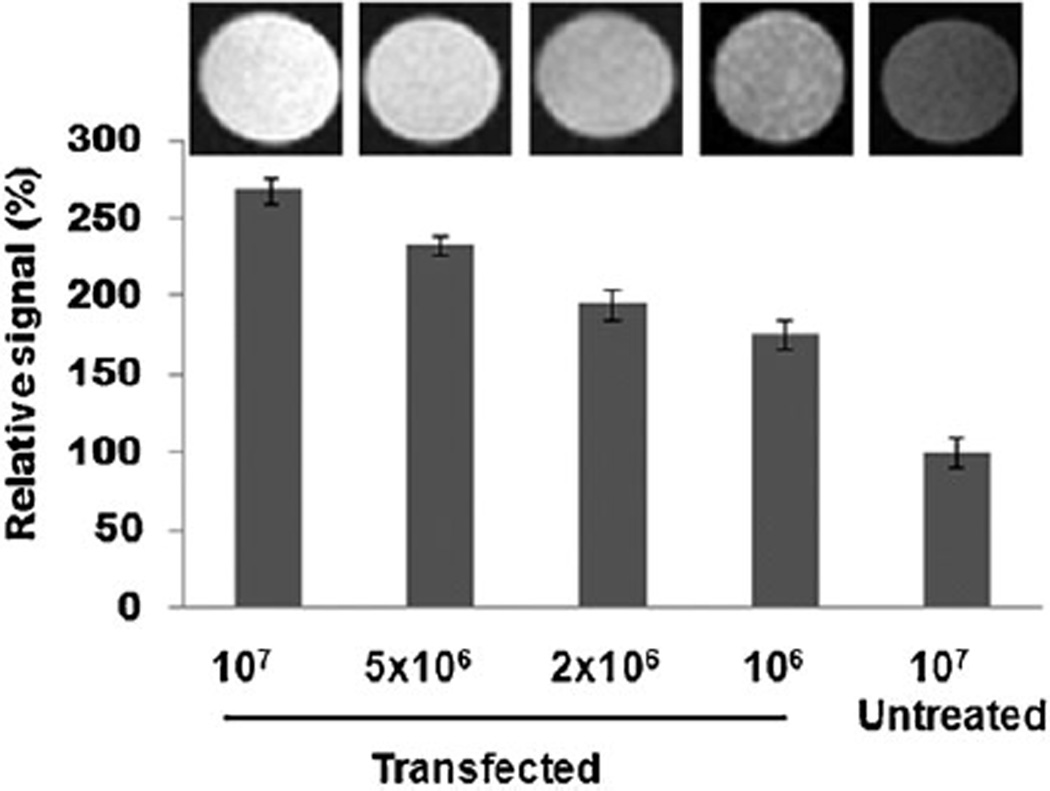

Finally, to evaluate the feasibility of using MRI to track the delivery of Luciferase siRNA, the MR signal intensity of 4T1-fluc cells treated with Alkyl-PEI2k-MnO/siRNA complexes was measured using a 7T MRI. As shown in Fig. 5, the T1-weighted MR images of the cells with internalized Alkyl-PEI2k-MnO/siRNA complexes presented signal enhancement with increased cell concentration. These results demonstrated that Alkyl-PEI2k-MnOs not only can deliver siRNA into 4T1-fluc cells but also can track the delivery efficiency by T1 MRI due to the strong positive T1 contrast effect.

Fig. 5.

Compared to the untreated group, the relative T1 signal intensity at different cell amounts after Alkyl-PEI2k-MnO/siRNA (N/P ratio = 10, siRNA = 6 pmol) transfection.

In summary, we successfully synthesized and characterized a new kind of siRNA delivery vehicle based on MONPs by using Alkyl-PEI2k as the hydrophilic coating. The cationic surface of the Alkyl-PEI2k-MnOs allows them to bind to siRNA effectively via electrostatic interactions, protecting them from enzymatic degradation. When the fluc-4T1 cells were treated with Alkyl-PEI2k-MnO/lucsiRNA complexes, reduced fluc gene expression and high T1 enhancement were detected. Additionally, our results also revealed low toxicity of Alkyl-PEI2k-MnOs. In conclusion, a safe and effective siRNA delivery vehicle was developed via a simple, facile method.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program (IRP), National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the International Cooperative Program of the National Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (81028009). R.X. was partially supported by the Chinese Scholarship Council (CSC) and NSFC (51172005), the National Basic Research Program of China (2010CB934602). G.L. was partially supported by projects from China (81101101 & 2011JQ0032).

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/c1cc15408g

Statement of the 12 authors: RX, GL, XC designed the experiments. RX, GL, AB, QQ, GZ, AJ, HB, AZ and AL performed the experiments. RX, GL, AB and QQ co-wrote the paper. And all authors discussed the data and proof-read the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Yanglong Hou, Email: hou@pku.edu.cn.

Xiaoyuan Chen, Email: shawn.chen@nih.gov.

Notes and references

- 1.Hao R, Xing R, Xu Z, Hou Y, Gao S, Sun S. Adv. Mater. 2010;22:2729–2742. doi: 10.1002/adma.201000260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu G, Swierczewska M, Lee S, Chen XY. Nano Today. 2010;5:524–539. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xie J, Liu G, Eden HS, Ai H, Chen X. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011 doi: 10.1021/ar200044b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu G, Xia C, Wang Z, Lv F, Gao F, Gong Q, Song B, Ai H, Gu Z. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Med. 2011;22:601–606. doi: 10.1007/s10856-010-4227-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tremel W, Schladt TD, Shukoor MI, Schneider K, Tahir MN, Natalio F, Ament I, Becker J, Jochum FD, Weber S, Kohler O, Theato P, Schreiber LM, Sonnichsen C, Schroder HC, Muller WEG. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010;49:3976–3980. doi: 10.1002/anie.200906689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bae KH, Lee K, Kim C, Park TG. Biomaterials. 2011;32:176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dorsett Y, Tuschl T. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2004;3:318–329. doi: 10.1038/nrd1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lieberman J, Song E, Lee SK, Shankar P. Trends Mol. Med. 2003;9:397–403. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4914(03)00143-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park TG. J. Controlled Release. 2008;129:75. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu G, Wang ZY, Lu J, Xia CC, Gao FB, Gong QY, Song B, Zhao XN, Shuai XT, Chen XY, Ai H, Gu ZW. Biomaterials. 2011;32:528–537. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu G, Xie J, Zhang F, Wang Z, Luo K, Zhu L, Quan Q, Niu G, Lee S, Ai H, Chen X. Small. 2011 doi: 10.1002/smll.201100825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu G, Yang H, Shao Y, Jiang H, Zhang XM. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging. 2010;5:53–58. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y, He ZJ, Xu B, Wu QZ, Liu G, Zhu H, Zhong Q, Deng DY, Ai H, Yue Q, Wei Y, Jun S, Zhou G, Gong QY. Brain Res. 2011;1391:24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JH, Na HB, An KJ, Park YI, Park M, Lee IS, Nam DH, Kim ST, Kim SH, Kim SW, Lim KH, Kim KS, Kim SO, Hyeon T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:5397–5401. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gu ZW, Luo K, Liu G, He B, Wu Y, Gong QY, Song B, Ai H. Biomaterials. 2011;32:2575–2585. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Z, Liu G, Sun J, Wu B, Gong Q, Song B, Ai H, Gu Z. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2009;9:378–385. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2009.j033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogris M, Walker G, Blessing T, Kircheis R, Wolschek M, Wagner E. J. Controlled Release. 2003;91:173–181. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(03)00230-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woods NB, Bottero V, Schmidt M, von Kalle C, Verma IM. Nature. 2006;440:1123. doi: 10.1038/4401123a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park TG, Mok H, Park JW. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007;18:1483–1489. doi: 10.1021/bc070111o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park TG, Mok H. Biopolymers. 2008;89:881–888. doi: 10.1002/bip.21032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park TG, Mok H, Lee SH, Park JW. Nat. Mater. 2010;9:272–278. doi: 10.1038/nmat2626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.