Abstract

It is generally accepted that proper activation of NMDA receptors (NMDARs) promotes neuronal survival and supports neuroplasticity, and excessive NMDAR activation leads to pathological outcomes and neurodegeneration. As NMDARs are found at both synaptic and extrasynaptic sites, there is significant interest to determine how NMDARs at different subcellular locations differentially regulate physiological as well as pathological functions. Better understanding on this issue may aid the development of therapeutic strategies to attenuate neuronal death or promote brain functions including cognition and mental health. Although the current prevailing theory emphasizes the major role of extrasynaptic NMDARs in neurodegeneration, there is growing evidence indicating the involvement of synaptic receptors. It is also evident that physiological functions of the brain also involve extrasynaptic NMDARs. Our recent study demonstrates that the degree of cell death following neuronal insults depends on the magnitude and duration of synaptic and extrasynaptic receptor co-activation. This re-kindles the interest to revisit the function of extrasynaptic NMDARs in cell fate. Furthermore, the development of antagonists that preferentially inhibit synaptic or extrasynaptic receptors may better clarify the role of NMDARs in neurodegeneration.

Keywords: calcium, excitotoxicity, extrasynaptic NMDAR, neurodegeneration, synaptic NMDAR

Introduction

NMDARs are the most important channels mediating glutamate excitotoxicity due to their widespread distribution in the central nervous system and high permeability to Ca2+. Overload of intracellular Ca2+ induced by excessive NMDAR activity is directly linked to the activation of intracellular events responsible for cell death (Szydlowska and Tymianski 2010). Complementing the notion that the degree of death correlates with the magnitude of NMDAR activation (Choi and Rothman 1990), NMDARs can bi-directionally regulate cell fate. While low concentrations of extracellular glutamate or NMDA activate the pro-survival molecules, higher concentrations progressively trigger the activation of pro-death molecules (Chandler and others 2001; Zhou and others 2013a).

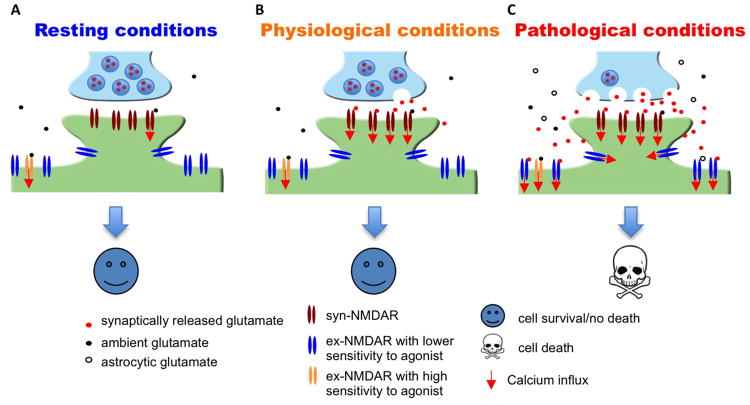

NMDARs are targeted to both synaptic and extrasynaptic sites. The synaptic NMDARs (syn-NMDARs) are located on the plasma membrane within 200-300 nm of the post-synaptic density (PSD). The extrasynaptic NMDARs (ex-NMDARs) are located on spine necks, dendritic shafts, or somas, which are further away from the PSD. Syn-NMDARs are activated by tonic and activity-dependent glutamate release from the presynaptic terminal. While certain populations of the ex-NMDARs are constitutively activated by ambient glutamate and contributes to the tonic currents (Sah and others 1989; Le Meur and others 2007; Papouin and others 2012), possibly the majority of ex-NMDARs are activated by glutamate spillover following intense synaptic activity or massive ectopic glutamate release following insults and brain trauma (Rossi and others 2007; Harris and Pettit 2008) (Figure 1). As the emerging proposals advocate that attenuation of excitotoxicity may be better achieved by targeting specific sub-populations of NMDARs rather than general inhibition, this review focuses on the function of syn- and ex-NMDARs in cell fate determination.

Figure 1. Massive and prolonged co-activation of syn-NMDARs and ex-NMDARs leads to cell death.

(A) It is estimated that the EC50 of glutamate to activate naïve as well as recombinant NMDAR is 2 to 4 μM, and that the ambient extracellular glutamate concentration is between 0.5 to 5 μM. Thus, under resting conditions, ambient glutamate may be sufficient to activate certain population of syn-NMDARs as well as ex-NMDARs. (B) Under physiological conditions, glutamate released from the presynaptic terminal activates syn-NMDARs. (C) Under pathological conditions, massive release of glutamate from both neuronal terminal and astrocytes leads to significant co-activation of syn- and ex-NMDARs. Short-term co-activation, which may occur during intensive brain activity and brief insult, does not necessarily lead to significant cell death. If the magnitude of receptor co-activation is correlated to the degree of cell death, inhibition of syn- or ex-NMDARs or partial co-inhibition will attenuate neurodegeneration. The existence of ex-NMDARs showing either high or low sensitivity to receptor agonist is suggested by that certain ex-NMDARs are activated by ambient glutamate (Sah and others 1989; Le Meur and others 2007) and certain ex-NMDARs are only activated by high level NMDA (Zhou and others 2013a).

The role of syn- and ex-NMDARs in cell death following pathological insults

It is known that the activation of NMDARs triggered by synaptic activities is required for normal brain function. Pharmacological manipulations that only activate syn-NMDARs is protective rather than causing cell death. While the tonic and constitutive activation of NMDARs in healthy brains (Sah and others 1989; Le Meur and others 2007) is maintained by ambient extracellular glutamate (at concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 5 μM) (Featherstone and Shippy 2008), glutamate levels exceeding 20 μM start to cause excitotoxicity. As the physiological activity-triggered presynaptic release results in glutamate level in the synaptic cleft reaching 1000 μM (Featherstone and Shippy 2008), exposure of syn-NMDARs alone to high concentration of agonists is unlikely to cause death (Figure 1).

It has been confirmed by many research groups that low glutamate (e.g. 10 to 20 μM) or NMDA (e.g. 10 to 20 μM) does not cause death in cultured neurons (Chandler and others 2001; Zhou and others 2013a). Increasing concentrations progressively causes incremented death, and the maximal death level can be observed after exposure to 50 to 100 μM NMDA (Zhou and others 2013a). These phenomena have raised several important questions. Does low agonist concentration only activate syn-NMDAR or ex-NMDAR or partially activate both? Does higher agonist concentration preferentially activate more syn-NMDAR or more ex-NMDAR or both? Is cell death triggered by high concentrations of agonist caused by the overactivation of syn-NMDAR or ex-NMDAR or the co-activation of both?

The prevailing theory, which is supported by data collected from many labs, emphasizes that glutamate excitotoxicity is predominantly regulated by ex-NMDARs. In a seminal study, Hardingham et al. found that the activation of syn-NMDARs by bicuculline treatment activates the pro-survival molecule CREB. Subsequent bath incubation with high concentration glutamate shuts off CREB signaling and causes severe neuronal death (Hardingham and others 2002). Although bath glutamate incubation likely activates both syn- and ex-NMDARs (see more detailed discussion later), the authors suggest that the activation of ex-NMDARs counteracts syn-NMDARs and suppresses pro-survival signaling. Inspired by this interesting initial study, numerous follow-up investigations have tried to isolate the ex-NMDARs and examined their role in cell death. To specifically block syn-NMDARs, neurons were first treated with bicuculline along with the irreversible use-dependent NMDAR antagonist MK-801. Hence, the subsequent bath application of NMDA or glutamate would only activate ex-NMDARs. It has been demonstrated that ex-NMDAR activation leads to significant death in neurons cultured from different brain regions (for a review, see Hardingham and Bading 2010).

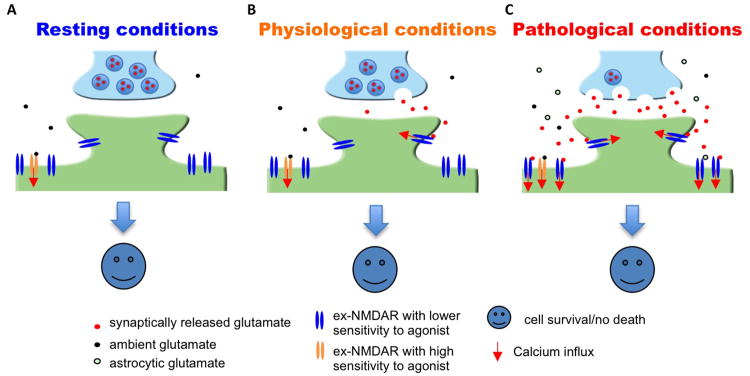

However, the “ex-NMDAR theory” on excitotoxicity has limitations in explaining some of the existing phenomena. First, it is known that ex-NMDARs are dominant receptors in young developing neurons, which are resistant to glutamate and NMDA insults (Hardingham and Bading 2002; Zhou and others 2009; Friedman and Segal 2010). Second, glutamate excitotoxicity is absent in retinal ganglion cells, in which there is no syn-NMDAR expression, and the NMDAR current is only mediated by ex-NMDARs (Chen and Diamond 2002; Ullian and others 2004). Thus, one can argue that the activation of ex-NMDARs alone is not sufficient to cause death (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Activation of ex-NMDARs in young or retinal ganglion neurons does not lead to cell death.

It is known that NMDAR function is mainly mediated through ex-NMDARs in young developing neurons and retinal ganglion neurons. It is known that, in these neurons, the activation of ex-NMDARs by ambient glutamate (A), synaptically released glutamate (B), or massive glutamate release from both synaptic terminals and astrocytes (C) does not trigger cell death.

Intriguingly, several studies even suggest the function of syn-NMDARs in excitotoxicity. Sattler et al. showed that decreasing the number of syn-NMDARs dampens the oxygen glucose deprivation (OGD)-induced cell death (Sattler and others 2000). By blocking syn-NMDARs with MK-801 or degrading ambient glutamate with glutamate pyruvate transaminase, a recent study demonstrated that syn-NMDARs participate in hypoxic excitotoxicity (Wroge and others 2012). Notably, Papouin et al. discovered that syn-NMDARs and ex-NMDARs in hippocampal neurons are differentially gated by the endogenous coagonist D-serine and glycine, respectively (Papouin and others 2012). They further demonstrated that syn-NMDARs are crucial for both synaptic potentiation and NMDA excitotoxicity. Cell death in hippocampal slices triggered by 50 μM NMDA was significantly reduced by RgDAAO (Rhodotorula gracilis D-amino acid oxidase), which degrades extracellular D-serine and in turn suppresses syn-NMDAR function. As the RgDAAO treatment may have only suppressed ∼60% synaptic NMDARs, it is not surprising that cell death was not eliminated. The authors further showed that BsGO (Bacillus subtilis glycine oxidase) inhibits ex-NMDARs through degrading extracellular glycine, and has marginal therapeutic effects on the NMDA-induced death. However, as BsGO only suppresses ∼55% of ex-NMDAR activity, one can argue that the remaining 45% activity may have led to almost full-scale death. Thus, the study convincingly demonstrates the role of syn-NMDARs in excitotoxicity, but does not rule out the involvement of ex-NMDARs.

By using cultured cortical neurons, Zhou and others (2013a) confirmed that the activation of syn-NMDARs does not cause cell death. Along with the syn-NMDAR activation, increasing amount of ex-NMDAR activation correlated with the increasing degree of cell death and the disruption of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis. After blocking syn-NMDARs, high concentrations of NMDA progressively activated increasing amount of ex-NMDARs but failed to trigger cell death and the disruption of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis. Blocking syn-NMDARs also totally rescued OGD-induced cell death. The results demonstrate that the activation of either syn-NMDARs or ex-NMDARs alone is not sufficient to cause excitotoxicity. Cell death depends on the co-activation of NMDARs at both synaptic and extrasynaptic sites (Figure 1). Hence, blocking either syn-NMDAR (Sattler and others 2000; Papouin and others 2012; Wroge and others 2012; Zhou and others 2013a) or ex-NMDAR (Tu and others 2010) attenuates excitotoxicity.

Role of ex-NMDARs in mediating physiological functions

The “ex-NMDAR theory” on excitotoxicity is not consistent with the fact that the ex-NMDARs are also involved in physiological functions of the brain. Prior to synapse formation, the activation of ex-NMDARs is crucial for neuronal development, such as synaptogenesis, neuritogenesis, and neuronal migration and differentiation. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that the activation of ex-NMDARs by glutamate spillover leads to the initiation of NMDA spikes in basal dendrites, which is crucial for the integration of synaptic input (Chalifoux and Carter 2011; Oikonomou and others 2012). As indicated by the studies of Fellin et al. and Angulo et al., the astrocytic glutamate-triggered ex-NMDAR activation causes synchronous firing, which is suggested as a fundamental element in information processing (Angulo and others 2004; Fellin and others 2004). Moreover, 25-200 Hz short bursts, which occur during exploratory behavior, are sufficient to activate ex-NMDARs. The authors suggest that cross-talk between synaptic and extrasynaptic receptors increases synaptic strength (Harris and Pettit 2008). Some recent studies demonstrate that ex-NMDARs play a major role in long-term depression (LTD), a cellular substrate of neuroplasticity (Papouin and others 2012; Liu and others 2013). In the visual cortex, the expression of ex-NMDAR is up-regulated following sensory stimulation. Such activity-dependent changes of ex-NMDAR are thought to prime the synapses for potentiation/strengthening (Eckert and others 2013). There is also evidence to support that the activation of ex-NMDARs by back propagating action potentials regulates dendritic excitability through down-regulation of h-channel conductance (Wu and others 2012). In addition to synaptic glutamate spillover, glutamate exocytosis from astrocytes also activates ex-NMDARs and controls synaptic activity and strength (Jourdain and others 2007).

It is important to note that ex-NMDAR activation may always be accompanied by syn-NMDAR activation, regardless of whether it is in physiological or pathological conditions (Figure 1). The lack of excitotoxicity following physiological co-activation of syn-NMDARs and ex-NMDARs may be due to the short duration and low degree of the co-activation. An in vitro study demonstrates that a brief receptor co-activation (e.g. less than 4 min exposure to toxic levels of NMDA) leads to the up-regulation of pro-survival rather than apoptotic signaling. Consistently, a very brief ischemic insult is neuro-protective (Zhou and others 2013a). Although the concentration of ambient extracellular glutamate is low in healthy brains, it is sufficient to cause tonic activation of NMDARs at the extrasynaptic locations (Sah and others 1989; Le Meur and others 2007; Papouin and others 2012). This suggests that even chronic constitutive activation of ex-NMDARs (presumably at low level though) is not neurotoxic.

Pharmacological differences between syn-NMDAR and ex-NMDAR

The physiological and pathological functions of syn- and ex-NMDAR may be better understood by examining the effects of specific inhibitors. As the co-activation of both receptors is required to trigger excitotoxicity, specific inhibition of the ex-NMDARs may offer favorable therapeutic effects to suppress NMDAR overactivation without hampering synaptic function. Among the available NMDAR antagonists, memantine has been used for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease, and suggested to preferentially block ex-NMDARs (Xia and others 2010). However, Wroge et al. found that memantine blocks EPSC mediated by either syn- or ex-NMDARs (Wroge and others 2012). Further, intracellular signaling triggered by either synaptic or extrasynaptic activation is suppressed by memantine (Zhou and others 2013a). Consistent with the notion that co-activation of both receptors is required for excitotoxicity, partial and simultaneous blockade of syn- and ex-NMDARs by low dose memantine suppresses NMDA-induced cell death (Zhou and others 2013a). The non-specific effects are also suggested by that memantine attenuates the synaptic NMDAR-mediated LTP (Frankiewicz and others 1996; Papouin and others 2012) and the extrasynaptic NMDAR-mediated LTD (Scott-McKean and Costa 2011; Papouin and others 2012; Liu and others 2013).

Better understanding of pharmacological and structural differences between syn- and ex-NMDAR may aid the development of specific inhibitors. Previous studies have suggested certain factors that may differentially affect the channel and pharmacological properties of synaptic and extrasynaptic receptors. The difference in channel property may be due to different density and component of scaffolding proteins that anchor NMDARs to dendritic spines and shafts (Gladding and Raymond 2011). The enrichment of NR3A subunits (Barria and Malinow 2002; Perez-Otano and others 2006), as well as specific splice variants and phosphorylation (Li and others 2002; Goebel-Goody and others 2009) in the ex-NMDARs may also render different agonist and co-agonist sensitivity from that of syn-NMDARs. Notably, it has been demonstrated that the ratio of synaptic to extrasynaptic NMDARs undergoes significant changes throughout neural development, partially due to the expression switches between NR2A and NR2B. Although some studies suggest that NR2A and NR2B regulate synaptic and extrasynaptic function as well as LTP and LTD, respectively. However, recent works demonstrate that NR2A and NR2B are present in both syn- and ex-NMDARs, and involved in regulating intracellular signaling mediated by either syn- or ex-NMDARs (Zhou and others, 2013b). Interestingly, Papouin and others (2012) have found that the syn-NMDARs are gated by co-agonist D-serine, whereas the ex-NMDARs are gated by glycine. This work suggests that NMDARs at different locations are pharmacologically different.

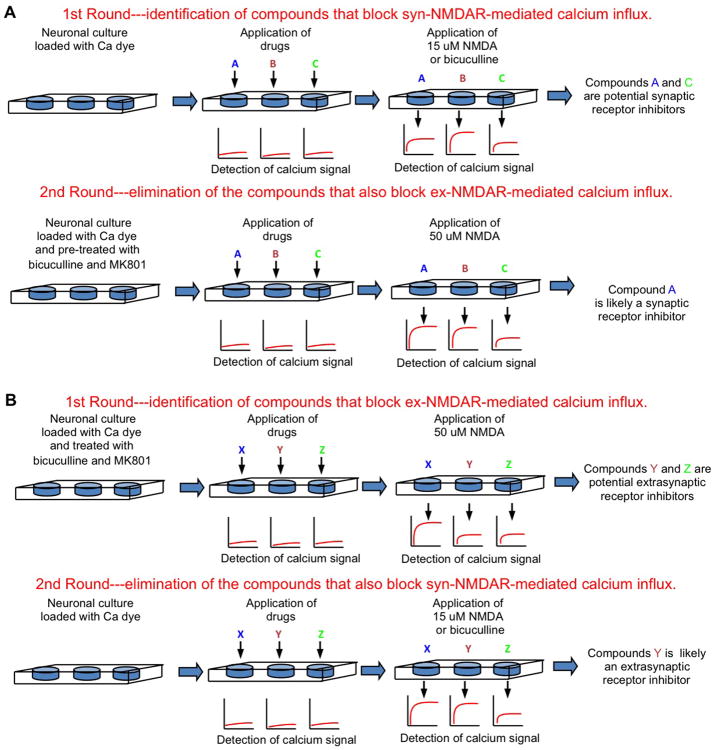

It is estimated that the EC50 of glutamate to activate the NMDARs is 2 to 4 μM. Glutamate at ∼50 μM triggers maximal response. As high but not low concentrations of NMDAR agonists are excitotoxic, the current understanding predicts that there may be at least two populations of ex-NMDARs. One is sensitive to low and ambient agonist, and responsible for tonic and constitutive NMDAR current (Le Meur and others 2007). The other is only activated by high level NMDA or glutamate, which may occur transiently in physiological conditions and chronically in neurodegenerative situations. By using the fluorescence-based imaging, Zhou and others (2013a) determined the NMDAR-mediated Ca2+ influx in live neurons. Neurons were first pre-treated with bicuculline and MK801 to block the synaptic receptors. MK801 in the pre-treatment cocktail should have also irreversibly blocked the active ex-NMDARs that mediate the tonic currents. The subsequent application of 15 μM NMDA failed to induce Ca2+ influx, but higher NMDA (from 20 to 50 μM) did. In another experiment, neurons were pre-treated with 15 μM NMDA and MK801, so that receptors sensitive to NMDA at ≤15 μM should be blocked. Subsequent application of bicuculline or 15 μM NMDA failed to cause Ca2+ influx, but 20-50 μM NMDA did. This indicates that the majority of the ex-NMDAR is sensitive to higher NMDA (i.e. > 15 μM), and low NMDA (at ≤ 15 μM) activates most of the syn-NMDARs. Based on this finding, we propose a simple high-throughput strategy to screen for synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDAR-specific inhibitors (Figure 3).

Figure 3. High-throughput screening strategies to identify inhibitors for synaptic or extrasynaptic NMDARs.

Primary cultured neurons are seeded in 96- or 384-well plates. The NMDAR-mediated Ca2+ influx will be detected by an automated plate reader using fluorescent Ca2+-sensitive dyes. (A) Strategy to screen for synaptic receptor inhibitors. (B) Strategy to screen for extrasynaptic receptor inhibitors.

The existence of ex-NMDARs with high and low agonist sensitivity may help to explain the different cell fate in normal and degenerative brains. As implicated in ischemic stroke, the massive glutamate release elevates extracellular concentration and may in turn activates ex-NMDARs that are not sensitive to the low ambient glutamate. The low sensitivity ex-NMDARs may also be transiently activated by significant glutamate spillover during exploration when bursts of synaptic transmission are detected (Harris and Pettit 2008). In the brains of Alzheimer's patients or animal models, there is a reduction of glutamate transporters, reduced glutamate uptake, and therefore an increase in ambient glutamate level, which is hypothesized to activate more ex-NMDARs (Parsons and Raymond 2014).

The higher agonist sensitivity in syn-NMDARs (than the “pathological” ex-NMDARs) may offer explanation to the dose-dependent cell death induced by bath NMDA application. In our opinion, bath incubation does not always trigger global NMDAR activation. Low NMDA (e.g. ≤15 μM) mainly activates synaptic NMDAR, and hence is neuroprotective rather than neurotoxic. Most of the “pathological” ex-NMDARs are only activated by higher levels of NMDA (i.e. > 20 μM). Thus, high but not low NMDA triggers receptor co-activation and causes excitotoxicity. Other evidence also supports that syn-NMDARs may be more sensitive to agonist than ex-NMDARs. While promoting glutamate efflux from a small population of astrocytes in neuron/glia co-cultures mainly activates syn-NMDARs, glutamate efflux from significantly more astrocytes causes ex-NMDAR activation (Gouix and others 2009).

Concluding remarks and future directions

Accumulating efforts are made to elucidate the role of syn- and ex-NMDARs in physiological and pathological functions. Although elevated ex-NMDAR activity is associated with neurodegeneration, analysis of the existing data suggests that the activation of ex-NMDAR alone may not lead to significant excitotoxicity. However, preferential inhibition of the overactivated ex-NMDARs may represent a favorable mean to battle neurodegeneration. In our opinion, specific and potent inhibitors targeting the ex-NMDARs are not available. The development of effective high-throughput screening strategies is greatly needed.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by start-up fund from Nanjing Medical University affiliated Changzhou Hospital (to XZ), Science and Technology Developmental Key Project of Nanjing Medical University (2013NJU212 to XZ), Changzhou Applied Basic Research Program (CJ20130023 to ZC), NIH grants (MH093445 and NS072668 to HW), and American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship (10POST4550000 to XZ).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- Angulo MC, Kozlov AS, Charpak S, Audinat E. Glutamate released from glial cells synchronizes neuronal activity in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6920–6927. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0473-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barria A, Malinow R. Subunit-specific NMDA receptor trafficking to synapses. Neuron. 2002;35:345–353. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00776-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalifoux JR, Carter AG. Glutamate spillover promotes the generation of NMDA spikes. J Neurosci. 2011;31:16435–16446. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2777-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler LJ, Sutton G, Dorairaj NR, Norwood D. N-methyl D-aspartate receptor-mediated bidirectional control of extracellular signal-regulated kinase activity in cortical neuronal cultures. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:2627–2636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003390200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Diamond JS. Synaptically released glutamate activates extrasynaptic NMDA receptors on cells in the ganglion cell layer of rat retina. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2165–2173. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02165.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi DW, Rothman SM. The role of glutamate neurotoxicity in hypoxic-ischemic neuronal death. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1990;13:171–182. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.13.030190.001131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert MJ, Guevremont D, Williams JM, Abraham WC. Rapid visual stimulation increases extrasynaptic glutamate receptor expression but not visual-evoked potentials in the adult rat primary visual cortex. Eur J Neurosci. 2013;37:400–406. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone DE, Shippy SA. Regulation of synaptic transmission by ambient extracellular glutamate. Neuroscientist. 2008;14:171–181. doi: 10.1177/1073858407308518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellin T, Pascual O, Gobbo S, Pozzan T, Haydon PG, Carmignoto G. Neuronal synchrony mediated by astrocytic glutamate through activation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors. Neuron. 2004;43:729–743. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankiewicz T, Potier B, Bashir ZI, Collingridge GL, Parsons CG. Effects of memantine and MK-801 on NMDA-induced currents in cultured neurones and on synaptic transmission and LTP in area CA1 of rat hippocampal slices. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;117:689–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman LK, Segal M. Early exposure of cultured hippocampal neurons to excitatory amino acids protects from later excitotoxicity. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2010;28:195–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladding CM, Raymond LA. Mechanisms underlying NMDA receptor synaptic/extrasynaptic distribution and function. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2011;48:308–320. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebel-Goody SM, Davies KD, Alvestad Linger RM, Freund RK, Browning MD. Phospho-regulation of synaptic and extrasynaptic N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors in adult hippocampal slices. Neuroscience. 2009;158:1446–1459. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouix E, Leveille F, Nicole O, Melon C, Had-Aissouni L, Buisson A. Reverse glial glutamate uptake triggers neuronal cell death through extrasynaptic NMDA receptor activation. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2009;40:463–473. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardingham GE, Bading H. Coupling of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors to a CREB shut-off pathway is developmentally regulated. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1600:148–153. doi: 10.1016/s1570-9639(02)00455-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardingham GE, Bading H. Synaptic versus extrasynaptic NMDA receptor signalling: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:682–696. doi: 10.1038/nrn2911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardingham GE, Fukunaga Y, Bading H. Extrasynaptic NMDARs oppose synaptic NMDARs by triggering CREB shut-off and cell death pathways. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:405–414. doi: 10.1038/nn835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AZ, Pettit DL. Recruiting extrasynaptic NMDA receptors augments synaptic signaling. J Neurophysiol. 2008;99:524–533. doi: 10.1152/jn.01169.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jourdain P, Bergersen LH, Bhaukaurally K, Bezzi P, Santello M, Domercq M, Matute C, Tonello F, Gundersen V, Volterra A. Glutamate exocytosis from astrocytes controls synaptic strength. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:331–339. doi: 10.1038/nn1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Meur K, Galante M, Angulo MC, Audinat E. Tonic activation of NMDA receptors by ambient glutamate of non-synaptic origin in the rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 2007;580:373–383. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.123570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Chen N, Luo T, Otsu Y, Murphy TH, Raymond LA. Differential regulation of synaptic and extra-synaptic NMDA receptors. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:833–834. doi: 10.1038/nn912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu DD, Yang Q, Li ST. Activation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors induces LTD in rat hippocampal CA1 neurons. Brain Res Bull. 2013;93:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oikonomou KD, Short SM, Rich MT, Antic SD. Extrasynaptic glutamate receptor activation as cellular bases for dynamic range compression in pyramidal neurons. Front Physiol. 2012;3:334. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papouin T, Ladepeche L, Ruel J, Sacchi S, Labasque M, Hanini M, Groc L, Pollegioni L, Mothet JP, Oliet SH. Synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA receptors are gated by different endogenous coagonists. Cell. 2012;150:633–646. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons MP, Raymond LA. Extrasynaptic NMDA Receptor Involvement in Central Nervous System Disorders. Neuron. 2014;82:279–293. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Otano I, Lujan R, Tavalin SJ, Plomann M, Modregger J, Liu XB, Jones EG, Heinemann SF, Lo DC, Ehlers MD. Endocytosis and synaptic removal of NR3A-containing NMDA receptors by PACSIN1/syndapin1. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:611–621. doi: 10.1038/nn1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi DJ, Brady JD, Mohr C. Astrocyte metabolism and signaling during brain ischemia. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1377–1386. doi: 10.1038/nn2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sah P, Hestrin S, Nicoll RA. Tonic activation of NMDA receptors by ambient glutamate enhances excitability of neurons. Science. 1989;246:815–818. doi: 10.1126/science.2573153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattler R, Xiong Z, Lu WY, MacDonald JF, Tymianski M. Distinct roles of synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA receptors in excitotoxicity. J Neurosci. 2000;20:22–33. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00022.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-McKean JJ, Costa AC. Exaggerated NMDA mediated LTD in a mouse model of Down syndrome and pharmacological rescuing by memantine. Learn Mem. 2011;18:774–778. doi: 10.1101/lm.024182.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szydlowska K, Tymianski M. Calcium, ischemia and excitotoxicity. Cell Calcium. 2010;47:122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu W, Xu X, Peng L, Zhong X, Zhang W, Soundarapandian MM, Balel C, Wang M, Jia N, Zhang W, Lew F, Chan SL, Chen Y, Lu Y. DAPK1 interaction with NMDA receptor NR2B subunits mediates brain damage in stroke. Cell. 2010;140:222–234. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullian EM, Barkis WB, Chen S, Diamond JS, Barres BA. Invulnerability of retinal ganglion cells to NMDA excitotoxicity. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;26:544–557. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wroge CM, Hogins J, Eisenman L, Mennerick S. Synaptic NMDA receptors mediate hypoxic excitotoxic death. J Neurosci. 2012;32:6732–6742. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6371-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YW, Grebenyuk S, McHugh TJ, Rusakov DA, Semyanov A. Backpropagating action potentials enable detection of extrasynaptic glutamate by NMDA receptors. Cell Rep. 2012;1:495–505. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia P, Chen HS, Zhang D, Lipton SA. Memantine preferentially blocks extrasynaptic over synaptic NMDA receptor currents in hippocampal autapses. J Neurosci. 2010;30:11246–11250. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2488-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Hollern D, Liao J, Andrechek E, Wang H. NMDA receptor-mediated excitotoxicity depends on the coactivation of synaptic and extrasynaptic receptors. Cell Death Dis. 2013a;4:e560. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Moon C, Zheng F, Luo Y, Soellner D, Nunez JL, Wang H. N-methyl-D-aspartate-stimulated ERK1/2 signaling and the transcriptional up-regulation of plasticity-related genes are developmentally regulated following in vitro neuronal maturation. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:2632–2644. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Ding Q, Chen Z, Yun H, Wang H. Involvement of the GluN2A and GluN2B subunits in synaptic and extrasynaptic N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor function and neuronal excitotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2013b;288:24151–24159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.482000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]