Significance

The rise of drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) underscores the critical need for a better understanding of essential physiological processes. Among these is cell-wall synthesis, the target of many antibiotics. To understand how Mtb orchestrates synthesis of its cell wall, we performed whole-genome interaction studies in cells with different peptidoglycan synthesis mutations. We found that different enzymes become required for bacterial growth in ΔponA1, ΔponA2, or ΔldtB cells, suggesting that discrete cell envelope biogenesis networks exist in Mtb. Furthermore, we show that these networks’ enzymes are differentially susceptible to cell-wall–active drugs. Our data provide insight into the essential processes of cell-wall synthesis in Mtb and highlight the role of different synthesis networks in antibiotic tolerance.

Keywords: Mycobacterium tuberculosis, transposon sequencing, genetic interaction, peptidoglycan, cell wall

Abstract

Peptidoglycan (PG), a complex polymer composed of saccharide chains cross-linked by short peptides, is a critical component of the bacterial cell wall. PG synthesis has been extensively studied in model organisms but remains poorly understood in mycobacteria, a genus that includes the important human pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). The principle PG synthetic enzymes have similar and, at times, overlapping functions. To determine how these are functionally organized, we carried out whole-genome transposon mutagenesis screens in Mtb strains deleted for ponA1, ponA2, and ldtB, major PG synthetic enzymes. We identified distinct factors required to sustain bacterial growth in the absence of each of these enzymes. We find that even the homologs PonA1 and PonA2 have unique sets of genetic interactions, suggesting there are distinct PG synthesis pathways in Mtb. Either PonA1 or PonA2 is required for growth of Mtb, but both genetically interact with LdtB, which has its own distinct genetic network. We further provide evidence that each interaction network is differentially susceptible to antibiotics. Thus, Mtb uses alternative pathways to produce PG, each with its own biochemical characteristics and vulnerabilities.

One of the leading causes of infectious disease deaths worldwide is tuberculosis (TB), caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). One-third of the human population is thought to harbor Mtb and ∼1.5 million individuals died of TB last year (1). Mtb’s success as a pathogen is due in part to its unusual cell wall, which is notorious for its complexity and is implicated in Mtb’s innate resistance to many commonly used antibiotics (2). A critical component of the bacterial cell wall (including Mtb’s) is peptidoglycan (PG), a complex polymer that provides structural support and counteracts turgor pressure (3). PG is essential for cell survival, and its synthesis is targeted by many potent antibiotics (2).

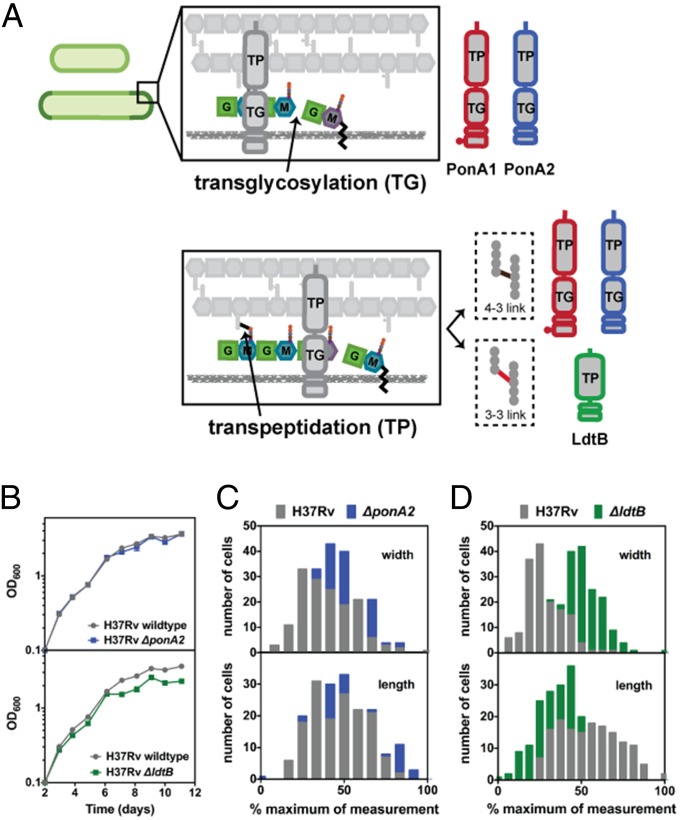

PG consists of long glycan chains composed of two different sugars (Fig. 1A) that are cross-linked via short peptide side chains that extend from the glycan chains. Notably, generation of mature PG occurs outside of the cell membrane and is mediated by enzymes that incorporate new PG subunits, which are formed in the cytoplasm, into the PG polymer. PonA1 and PonA2 are the two enzymes in Mtb that can both polymerize glycan strands and cross-link peptides [known as bifunctional penicillin binding proteins (PBPs), Fig. 1A]. The predominant peptide cross-links in mycobacteria join the third amino acids (3–3 link) of adjacent stem peptides (4, 5), which are synthesized by l,d-transpeptidases (Ldts) such as LdtB, one of the major Ldts in Mtb (Fig. 1A). The peptides can also be joined by cross-linking the fourth and third amino acids (4–3 link) (Fig. 1A) through the action of bifunctional or monofunctional (capable of only peptide cross-linking) PBPs. The activity of these distinct factors must be coordinated to ensure proper cell-wall synthesis. One method of coordination is the use of large protein complexes, the elongation complex and divisome, which mediate cell-wall biogenesis during cell elongation or division, respectively (2). The essential activity of these enzymes makes them prime drug targets; indeed, PBPs and Ldts are inhibited by carbapenems and penicillin (6, 7), which remains one of the most clinically important drugs in use.

Fig. 1.

Deletion of PG synthases influences growth and morphology of Mtb. (A) Transglycosylation (TG) and transpeptidation (TP) reactions incorporate new PG subunits into the cell wall. PonA1 and PonA2 carry out both TG and 4–3 TP reactions. LdtB only mediates 3–3 TP reactions. M, N-acetylmuramic acid. G, N-acetylglucosamine. (B) Deletion of either ponA2 or ldtB does not greatly affect Mtb growth during log phase, although loss of ldtB reduces population density in stationary phase. Error bars are often too small to see. (C) ponA2 mutant cells (n = 179) have increased width compared with wild-type cells (n = 153) (approximate P value <0.0001 by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). (D) ldtB mutant cells (n = 193) have increased width and decreased length compared with wild-type cells (n = 153) (approximate P value <0.0001 by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for both length and width).

Although the biosynthesis and structure of PG have been investigated for decades, predominantly in organisms such as Escherichia coli or Bacillus subtilis, the mechanisms that coordinate the biochemical activities required to polymerize and modify the cell wall remain incompletely understood. Moreover, much less is known about PG synthesis in many pathogenic organisms, including Mtb (2). However, previous studies in Mtb suggest that PG synthesis in this pathogen does not strictly conform to the E. coli paradigm. For example, E. coli has three bifunctional PBPs [PBP1A, PBP1B, and PBP1C (3)], whereas Mtb has just two [PonA1 and PonA2 (8)]. Additionally, PBP2 (known as PBPA in mycobacteria) is a monofunctional PBP and is required for cell elongation in E. coli, but instead seems to function in cell septation in mycobacteria (3, 9).

The structure of PG is also different in Mtb than in E. coli: Mycobacterial PG has an unusual prevalence of 3–3 peptide linkages. The abundance of 3–3 cross-links in mycobacterial PG throughout different growth stages (5) suggests that Ldts are active during normal growth; however, their cellular roles or regulation during growth and PG biogenesis remain largely unknown. Whereas penicillins and cephalosporins target only enzymes that produce 4–3 cross-links, Ldts can be targeted by carbapenems (7). Recent work suggests that these agents might be far more efficacious against both dividing and nondividing bacteria (10). Although little is known about Mtb’s five encoded Ldts (11), one, LdtB, is implicated in antibiotic tolerance (11–13), is required for normal virulence in a mouse model of TB (12), and is important for normal cell shape (13).

Previous studies have also revealed that PG biosynthesis differs between Mtb and the related saprophytic Mycobacterium smegmatis (Msm). As opposed to Mtb, Msm has three bifunctional PBPs: PonA1, PonA2, and PonA3 (14). PonA1 is required for Msm but not Mtb growth in culture (15, 16); however, PonA1 is required for robust growth of Mtb during infection (16). In contrast, Mtb and Msm ponA2 mutants do not have growth defects in culture (14, 17). However, Mtb strains with inactivated ponA1 or ponA2 exhibit similar survival defects during growth in a host (16, 18), suggesting that these two similar bifunctional enzymes have nonredundant and important contributions to PG synthesis during infection. Collectively, the differences in PG synthase functionality may imply that different PG synthetic pathways exist across species, which may have consequences for a pathogen’s virulence during infection.

Here, we interrogated PG synthesis in Mtb by investigating the genetic interactions of ponA1, ponA2, and ldtB, which encode three PG synthases critical for Mtb’s growth during infection. To identify these interactions, we performed genome-wide transposon mutagenesis screens in Mtb mutant strains that lacked one of these enzymes. Advances in high-throughput sequencing technology coupled with the power of whole-genome studies provide unique insights into key bacterial processes, such as cell-wall biosynthesis. Such studies have been performed to a limited extent in bacteria, and further work would substantially expand our understanding of the organization of prokaryotic metabolic processes. In this study, we identified diverse genetic interaction networks for ponA1, ponA2, and ldtB, suggesting that these synthases are embedded within distinct cellular networks for assembling Mtb’s PG. We found that either ponA1 or ponA2 is required for cell growth, and that ldtB interacts with both ponA1 and ponA2. Moreover, mutants that lack these enzymes have differential susceptibility to agents that interfere with cell-wall biogenesis. Thus, the Mtb cell wall is synthesized using multiple interacting networks that are both overlapping and unique.

Results

PonA1, PonA2, and LdtB Are Individually Dispensable for Growth of Mtb.

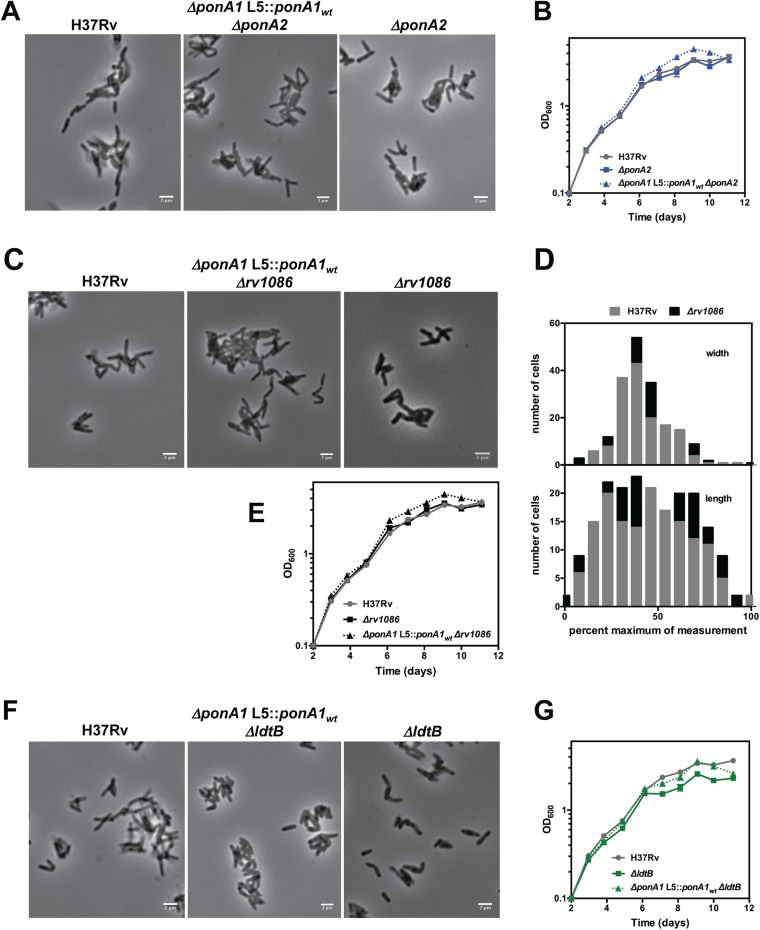

PonA1, its homolog PonA2, and LdtB can generate bonds between new PG subunits and those in the existing PG polymer (Fig. 1A). We generated independent ponA2 and ldtB deletion mutants and assessed their growth. As suggested by previous studies (14, 18) absence of either gene did not substantially affect Mtb’s exponential growth, although loss of LdtB diminished population density in stationary phase (Fig. 1B). However, ΔponA2 cells were moderately wider than wild-type Mtb (Fig. 1C). In contrast, ΔponA1 cells are longer than wild-type cells (16), suggesting these two homologous enzymes have distinct roles in PG synthesis in Mtb. Mutant cells that lack LdtB were significantly shorter [as previously reported (13)] and wider than wild-type cells (Fig. 1D), indicating that LdtB affects cell-wall synthesis and cell shape in a manner distinct from the two bifunctional PBPs. Thus, even though deletion of ponA1 (16), ponA2, or ldtB is compatible with cell growth, their individual deletions have detectable and distinct physiological effects.

Whole-Genome Mutagenesis Identifies PG Biogenesis Pathways in Mtb.

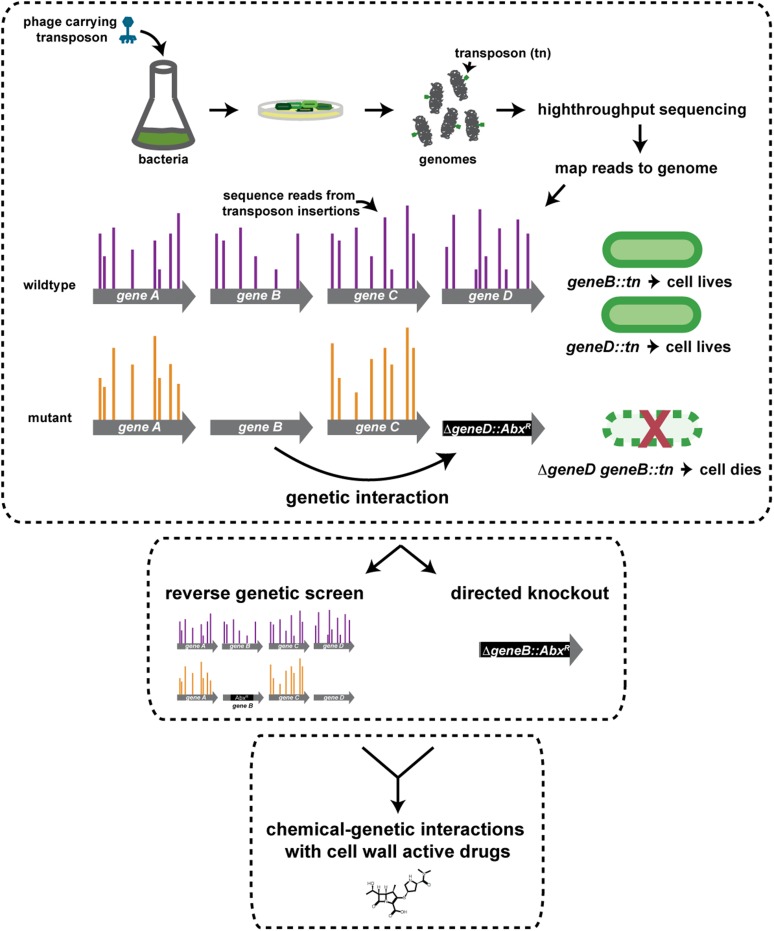

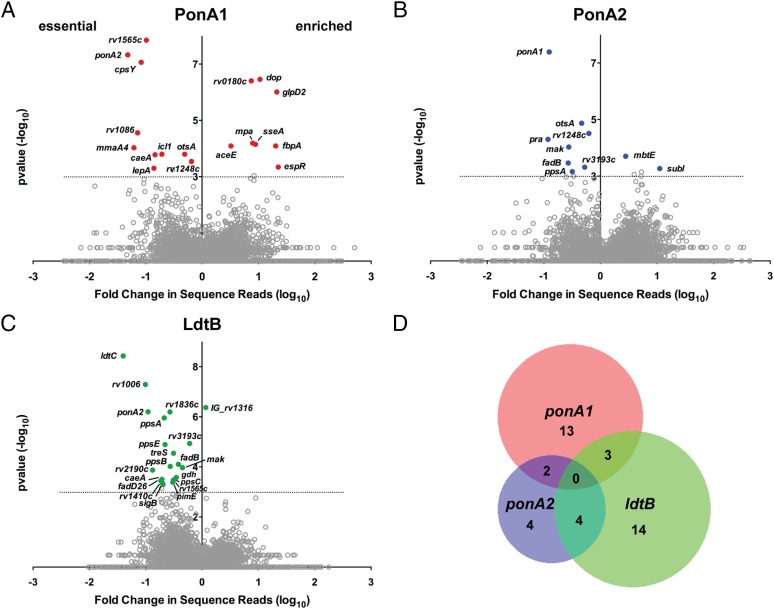

In E. coli, the PonA1 and PonA2 homologs, PBP1a and PBP1b, seem to function in different subcellular complexes and have been shown to have distinct interaction partners (3). We hypothesized that, in a similar fashion, PonA1 and PonA2 genetically interact with different pathways. To elucidate the shared and distinct roles of PonA1, PonA2, and LdtB in Mtb PG biogenesis, we used transposon mutagenesis and high-throughput sequencing in ΔponA1, ΔponA2, and ΔldtB Mtb strains to define the genetic interactions of these enzymes on a genome-wide scale (19, 20) (Figs. S1 and S2). These experiments measure bacterial fitness across a population. Genes that contain fewer than expected transposon insertions have a growth disadvantage (here termed “essential”) whereas those with larger numbers of insertions have an advantage (“enriched”). Comparisons of the transposon insertion profiles (21, 22) of the wild-type and mutant strains revealed both essential and enriched genes—two types of genetic interaction—in each strain (Fig. 2).

Fig. S1.

Schematic of genetic and chemical interaction studies in Mtb. Genome-wide genetic interactions are mapped by comparing the frequencies of transposon insertions in all loci in different genetic backgrounds using transposon mutagenesis and high-throughput sequencing. Genetic interactions can be identified by differential transposon insertion profiles in a gene in wild-type versus mutant cells. Genetic interactions can be confirmed by complementary reverse whole-genome screens or targeted knockouts. Cellular assays, for example with drug inhibition of cell-wall synthesis, can illuminate the relative contribution of genetic interactors to the targeted cell pathway. AbxR, antibiotic resistance cassette.

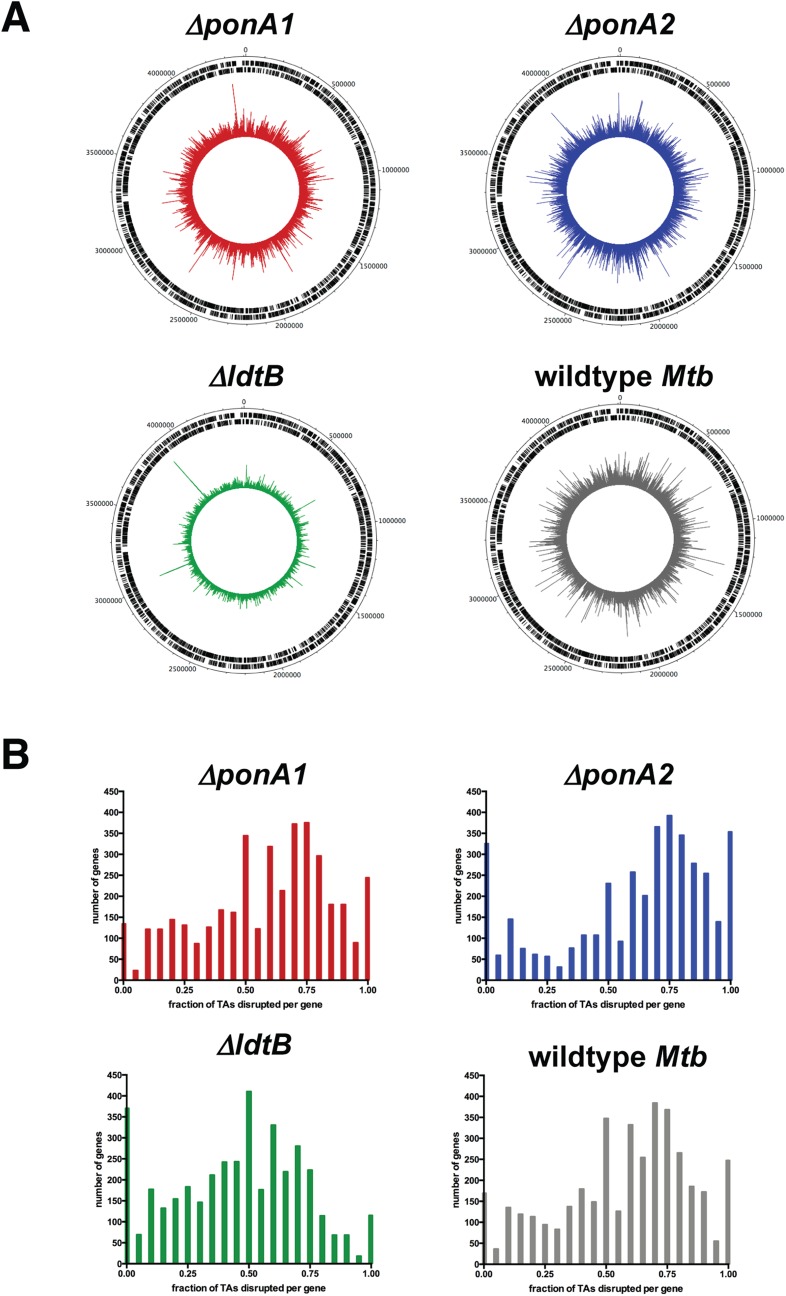

Fig. S2.

The transposon libraries are highly saturated. (A) The chromosomal distribution of sequence reads from the libraries was visualized with DNAPlotter. (B) The fraction of possible insertion sites (TA dinucleotides) that were actually disrupted by transposons was calculated per gene and plotted. The ΔponA1 library’s saturation is circa 70%. The ΔponA2 library is about 78% saturated. The ΔldtB library is circa 55% saturated, and wild-type Mtb is around 70% saturation.

Fig. 2.

ponA1, ponA2, and ldtB have largely distinct genetic interactions. Loci whose sequence reads were significantly different between wild-type and mutant cells [(A) ΔponA1, red circles; (B) ΔponA2, blue circles; (C) ΔldtB, green circles] with a P value <0.001 (represented by the dotted line) by the Mann–Whitney u test are plotted according to their P value and fold change in sequence reads from wild type (calculated from the geometric mean). Gray circles, nonsignificant loci. Gray circles above the dotted line are loci that are <90% significant in the simulations (SI Materials and Methods). (D) Venn diagram representation of the distinct interaction networks of ponA1, ponA2, and ldtB.

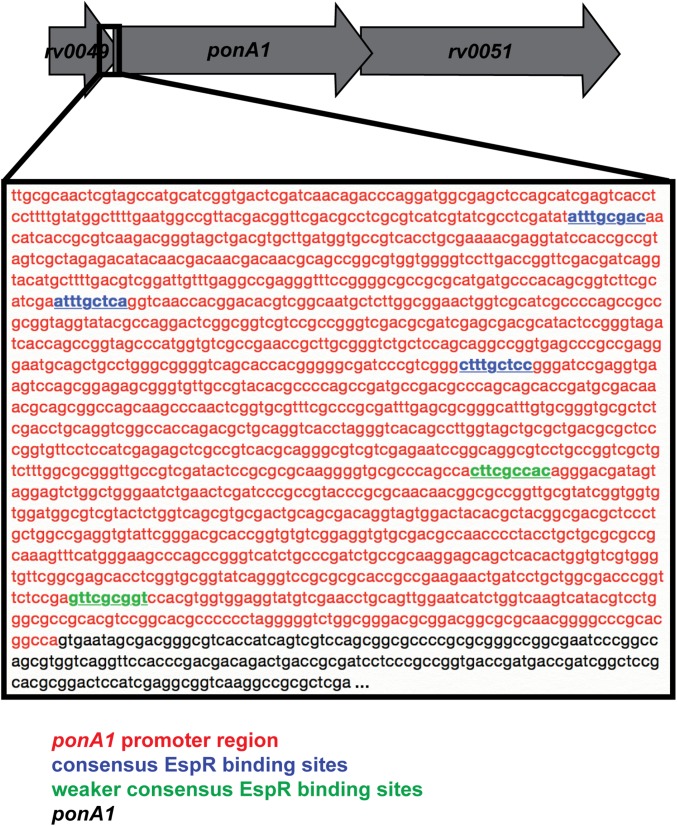

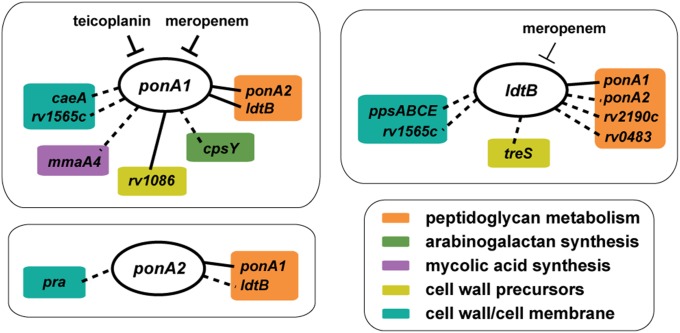

We identified 10 factors required in cells that lack PonA1 (Fig. 2A, essential factors). Most of these factors are associated with or predicted to be involved in cell-wall synthesis. For example, factors involved in peptidoglycan (PonA2), mycolic acid (MmaA4), and, potentially, arabinogalactan (CpsY) synthesis in addition to cell-wall precursor production (Rv1086) were found to be required in ΔponA1 cells (Fig. 2A). These data suggest that the cell requires either PonA1 or PonA2 for PG synthesis, analogous to the situation in E. coli (3). We also identified eight factors whose disruption in the ΔponA1 mutant seemed beneficial to the cell (Fig. 2A, enriched). For example, the transcription factor EspR (rv3849) had higher levels of transposon insertions in cells that lack ponA1 compared with wild-type Mtb, suggesting that cells that lack EspR may grow more rapidly than wild-type cells under these conditions. This could indicate that EspR regulates ponA1 transcription. Indeed, we found multiple canonical EspR binding sites (23) in the ponA1 promoter region (Fig. S3).

Fig. S3.

EspR may regulate ponA1 transcription. Several canonical EspR binding sites exist in the ponA1 promoter region at distances previously observed (23). See ref. 16 for the correct ponA1 transcriptional start site because it is misannotated in the H37Rv genome.

Our screen identified widely different genetic connections for ponA2 compared with ponA1. As predicted from the screen performed in ΔponA1 cells, ponA1 was required in ΔponA2 cells (Fig. 2B). Relatively few factors were shared between ΔponA1 and ΔponA2 cells. For example, rv3490 and rv1248c were required in both backgrounds. However, there were many differences, such as cpsY, rv1086, pra, and fadB, and the differences were in both the essential and enriched classes (Fig. 2 A and B). Thus, although either PonA1 or PonA2 is required for Mtb growth, both enzymes have predominantly different genetic interactions.

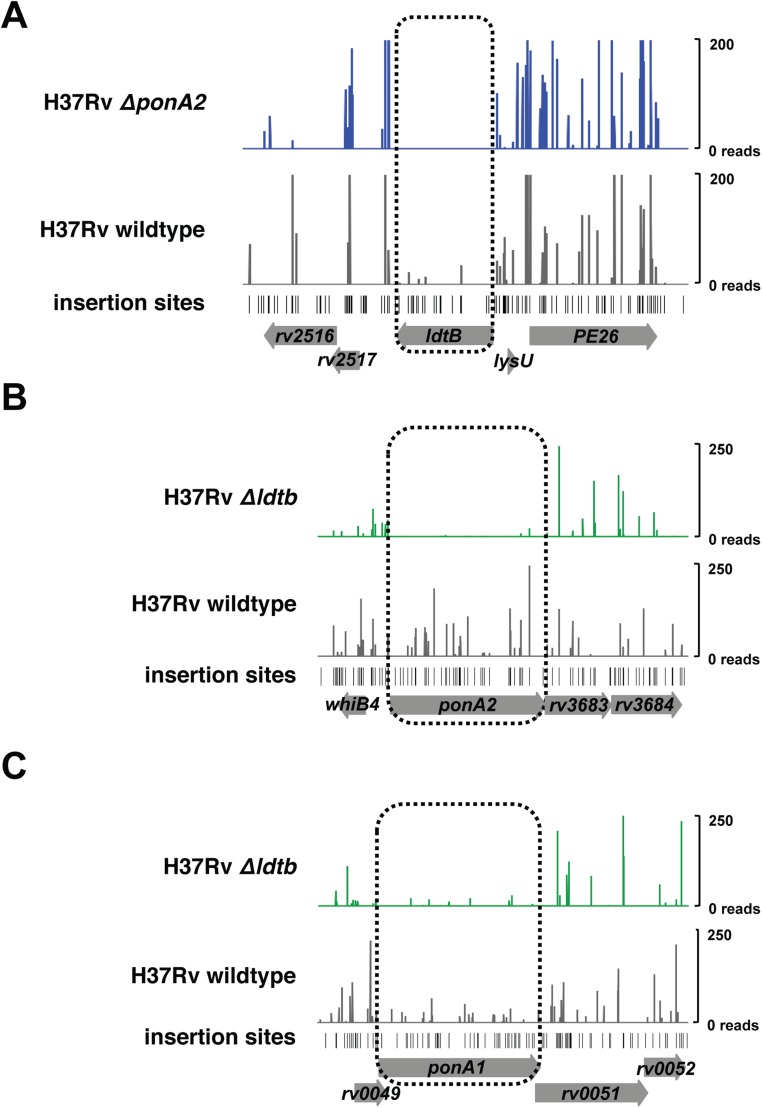

ldtB also interacts with a number of loci including some, such as ponA2, that overlap with ponA1 interactions (Fig. 2C). In the absence of either of the bifunctional enzymes that form 4–3 cross-links, 3–3 cross-linking may become more important for maintaining cell integrity. In addition, ldtB interacts with genes involved in cell-wall precursor synthesis (treS) and other steps in peptidoglycan metabolism, including the NlpP60 hydrolase Rv2190c (24). Collectively, these data show that the PG synthases PonA1, PonA2, and LdtB participate in largely distinct genetic networks (Fig. 2D).

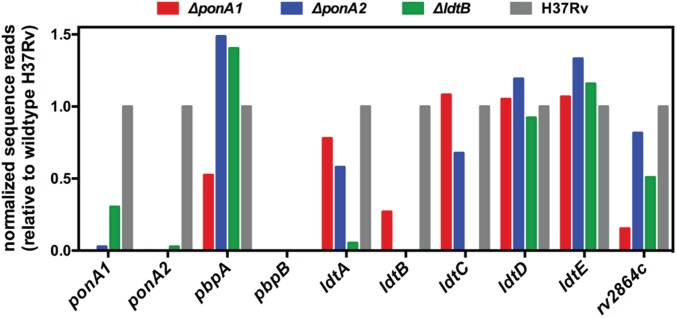

PG Synthases Are Variably Required in ponA1, ponA2, or ldtB Mutant Cells.

We took advantage of the depth and saturation of the mutant libraries to establish the relative contributions of PBPs and Ldts to bacterial fitness in the different mutant strain backgrounds. We analyzed the frequency of transposon insertions in the four PBP and five Ldt loci as well as a putative penicillin binding protein (Rv2864c) in each mutant strain. We found that particular PG synthases had differential insertion profiles in cells that lack ponA1, ponA2, or ldtB (Fig. 3). For example, transposon disruption of pbpA generated a relative growth disadvantage in ponA1 mutant cells compared with wild type whereas transposon disrupted pbpA exhibited growth advantages in ponA2 and ldtB mutant cells. These data suggest that PBPA may be more important for PG synthesis in cells without PonA1 than in cells without PonA2 or LdtB. Our data also support a role for rv2864c in PG synthesis. In ponA1 mutant cells, rv2864c was disrupted at just 15% of the wild-type frequency but was disrupted at 82% or 51% of the wild-type frequency in ponA2 or ldtB mutant cells, respectively (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Importance of PG synthases in ponA1, ponA2, or ldtB mutant cells. Sequence reads corresponding to transposon insertions at the indicated loci in the ΔponA1, ΔponA2, and ΔldtB mutant cells. Sequence reads at each locus are normalized to the respective locus in wild-type H37Rv cells.

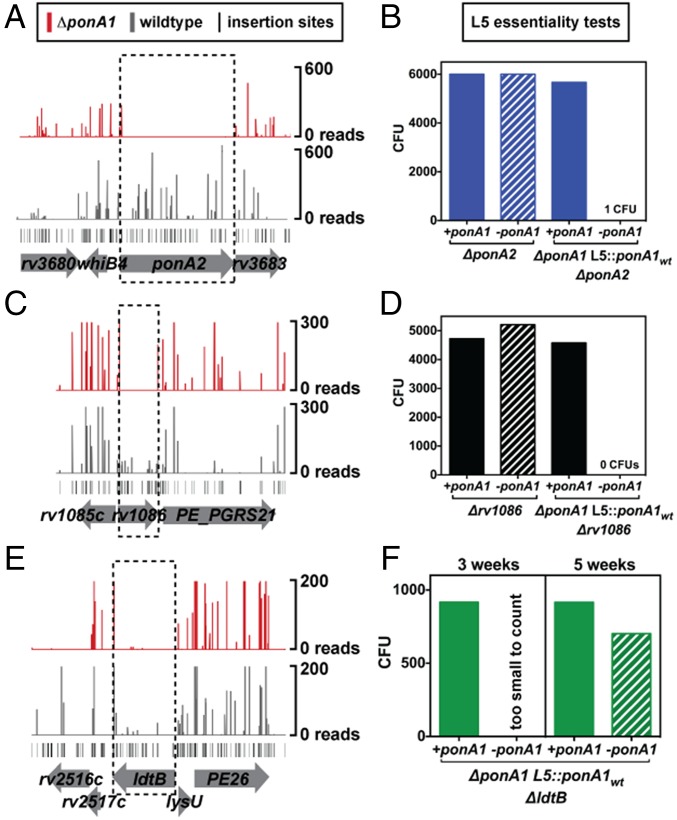

PonA2 Is Required for PG Synthesis in the Absence of PonA1.

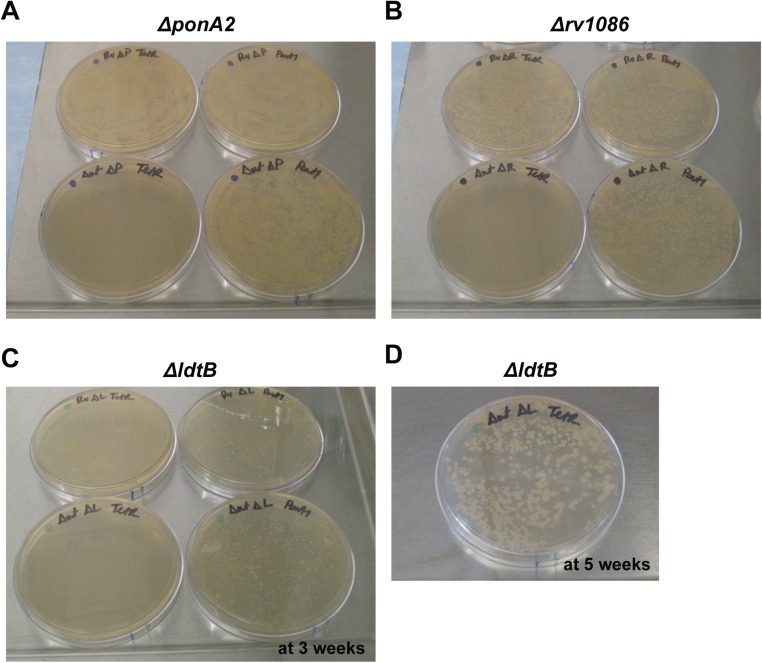

We chose select genes for individual validation of essentiality using a previously described allelic exchange method (16, 25) (Fig. 4A and Fig. S4). For example, we generated a ponA2 deletion in a strain whose only copy of ponA1 is at the L5 phage integration site (ΔponA1 L5::ponA1wt). We also generated a ponA2 deletion in wild-type H37Rv Mtb as a control. We assessed the impact of ponA2 loss in the mutant background and found that ΔponA1 L5::ponA1wt ΔponA2 cells grew at rates similar to and exhibited rod-shaped morphology similar to wild-type Mtb (Fig. S5 A and B). However, although we could integrate a wild-type ponA1 copy into the L5 site in ΔponA2 or ΔponA1 L5::ponA1wt ΔponA2 backgrounds (Fig. 4B and Fig. S6A), when we transformed an L5 empty vector we only obtained a significant number of colonies in the ΔponA2 cells that still encode ponA1 at the original locus (Fig. 4B and Fig. S6A). This confirms that PonA2 is required in the absence of PonA1 in Mtb and that even though these enzymes participate in largely distinct genetic networks they have at least partially complementary roles in PG biogenesis in Mtb.

Fig. 4.

Diverse cell-wall synthesis factors become required in ΔponA1 cells. (A) Transposon insertions (vertical bars), determined from high-throughput sequencing, are visualized at the ponA2 locus in either wild-type (gray) or ΔponA1 (red) cells. (B) Colony-forming units (CFUs) were counted from allelic exchanges with L5-integrating vectors that do or do not encode ponA1 in the experimental ΔponA1 L5::ponA1wt ΔponA2 strain or the control ΔponA2 strain (both control strain transformations had lawn growth, and CFUs were arbitrarily set to 6,000). (C) Transposon insertions at the rv1086 locus in wild-type (gray) and ΔponA1 (red) cells. (D) CFU counts from L5 allelic exchanges in the experimental ΔponA1 L5::ponA1wt Δrv1086 strain or the control Δrv1086 strain. (E) Transposon insertions at the ldtB locus in wild-type (gray) or ΔponA1 (red) cells. (F) CFU counts from L5 allelic exchanges in the experimental ΔponA1 L5::ponA1wt ΔldtB strain.

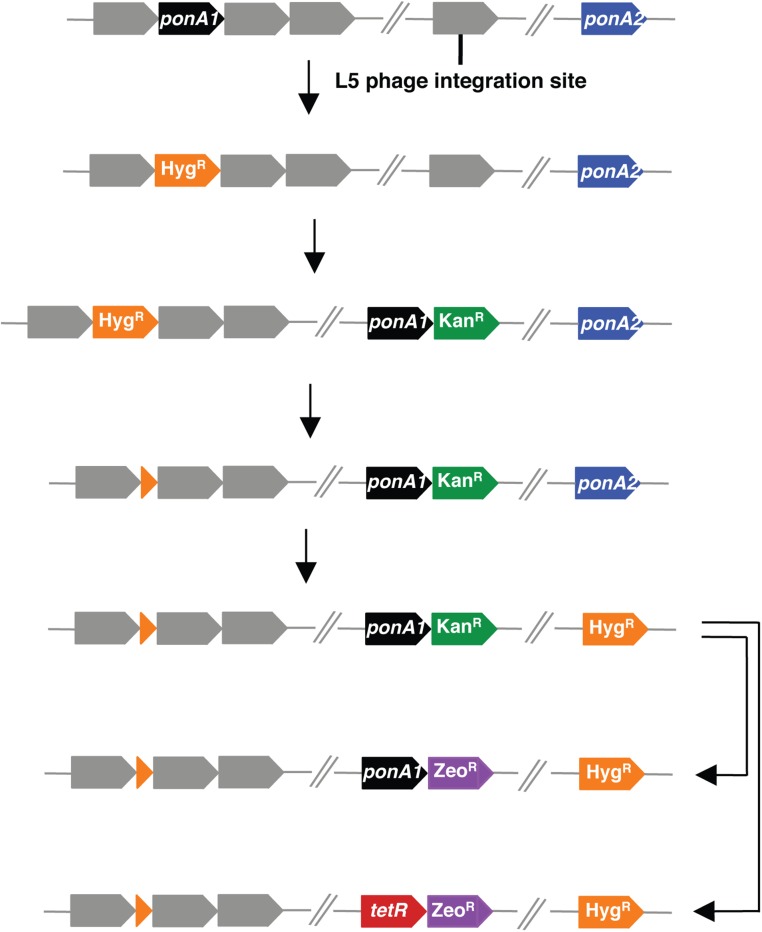

Fig. S4.

The endogenous locus of ponA1 is replaced with a hygromycin resistance cassette (HygR) flanked by LoxP sites. A kanamycin (KanR)-marked copy of ponA1 is integrated at the L5 phage site. The HygR is removed from the chromosome by Cre recombinase. The gene of interest (ponA2 is diagrammed here as an example) is replaced with HygR. The resulting strain is transformed with a vector that integrates at the same L5 phage integration site that encodes a zeocin (ZeoR)-marked ponA1 or the negative control gene tetR. If the gene of interest is required in the absence of ponA1, cells will not grow when transformed with the tetR vector.

Fig. S5.

Loss of individual factors does not dramatically alter cell fitness. (A) Cell morphology for wild-type Mtb, ΔponA1 L5::ponA1wt ΔponA2, and ΔponA2 cells was analyzed by light microscopy. (Scale bars, 2μm.) (B) Population growth of wild-type H37Rv, ΔponA2, and ΔponA1 L5::ponA1wt ΔponA2 cells in standard laboratory media (wild type and ΔponA2 reproduced from Fig. 1B). (C) Cell morphology for wild-type Mtb, ΔponA1 L5::ponA1wt Δrv1086, and Δrv1086 cells was analyzed by light microscopy. (Scale bars, 2μm.) (D) Cell length and width of wild-type and Δrv1086 cells were quantitated. No significant difference in either measurement was found (n = 188 cells). (E) Population growth of wild-type H37Rv, Δrv1086, and ΔponA1 L5::ponA1wt Δrv1086 cells in standard laboratory media. (F) Cell morphology for wild-type Mtb, ΔponA1 L5::ponA1wt ΔldtB, and ΔldtB cells was analyzed by light microscopy. (Scale bars, 2μm.) (G) Population growth of wild-type, ΔldtB, and ΔponA1 L5::ponA1wt ΔldtB cells in standard laboratory media (wild type and ΔldtB reproduced from Fig. 1B).

Fig. S6.

ponA1 is critical in cells that lack ponA2, rv1086, or ldtB. Transformation plates from allelic exchanges in (A) ΔponA2 (top) or ΔponA1 L5::ponA1wt ΔponA2 cells (bottom) with +ponA1 (right) or +tetR (left) vectors, (B) Δrv1086 (top) or ΔponA1 L5::ponA1wt Δrv1086 cells (bottom) with +ponA1 (right) or +tetR (left) vectors, or (C) ΔldtB (top) or ΔponA1 L5::ponA1wt ΔldtB cells (bottom) with +ponA1 (right) or +tetR (left) vectors at 3 wk. (D) The plate from the tetR transformed ΔponA1 L5::ponA1wt ΔldtB cells was left at 37 °C for 5 wk.

Rv1086 Is Required for Cell-Wall Synthesis in Cells That Lack PonA1.

Rv1086, a Z-isoprenyl diphosphate synthase, carries out the first committed step in the synthesis of the lipid carrier for cell-wall precursors (26). As with ponA2, we used allelic exchange to test whether rv1086 was required in cells that lack ponA1 (Fig. 4C). Indeed, we obtained robust growth only when we transformed ΔponA1 L5::ponA1wt Δrv1086 cells [which grew similarly to and exhibited cell shape similar to wild-type Mtb (Fig. S5 C–E)] with another ponA1 copy (Fig. 4D and Fig. S6B). These data demonstrate that rv1086 is required in cells that lack ponA1 and may indicate that PonA2 requires a dedicated pool of precursors.

LdtB Is Critical for Normal Bacterial Fitness in Cells Without PonA1.

An important prediction of the findings from our ΔponA1 and ΔponA2 screens is that both strains require ldtB for optimal growth (Fig. 4E and Fig. S7). Whereas bifunctional PBPs are critical in many bacterial species (3), mycobacterial PG exhibits very different architecture with its prevalence of 3–3 cross-links (4, 5). Using allelic exchange, we found that only tiny ΔponA1 ΔldtB colonies could be seen after 21 d of growth, when ΔldtB colonies were already large (Fig. 4F and Fig. S6C); these colonies required 35 d to reach a similar size (Fig. S6D). Thus, ldtB is required for robust growth in the absence of ponA1.

Fig. S7.

ldtB genetically interacts with ponA1 and ponA2. Sequence reads that represent individual transposon insertions are visualized at the (A) ldtB locus in wild-type (gray) or ΔponA2 (blue) cells, (B) ponA2 locus in wild-type (gray) or ΔldtB (green) cells, or (C) the ponA1 locus in wild-type (gray) or ΔldtB (green) cells.

Distinct Cell-Wall Synthesis Networks Exhibit Differential Tolerance to Cell-Wall–Active Drugs.

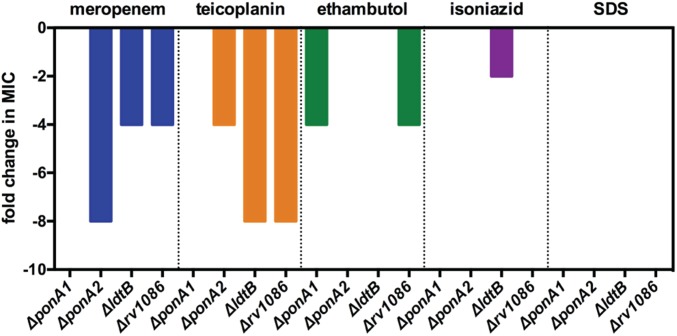

Our data suggest that PonA1, PonA2, and LdtB participate in distinct genetic networks with partially overlapping but largely unique genetic interactions for each enzyme. We hypothesized that these networks would have different cellular activity and could therefore be differentially susceptible to drugs that target cell-wall synthesis. To test this hypothesis, we treated cells that lack ponA1, ponA2, ldtB, or other members of their interaction networks with drugs that inhibit the various components of Mtb’s cell wall, including meropenem, which blocks PG transpeptidases; teicoplanin, which binds directly to PG to prevent further cross-linking (10, 27); ethambutol, which targets arabinogalactan synthesis; and isoniazid, which targets mycolic acid synthesis. We found that ΔponA1 cells had the same minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for meropenem and teicoplanin as wild-type Mtb (Fig. 5); however, ΔponA2 and ΔldtB cells were four- to eightfold more susceptible to both meropenem and teicoplanin. Furthermore, mutants that lack ponA1 exhibit a fourfold increased susceptibility to ethambutol. However, the ΔponA2 or ΔldtB mutants do not exhibit heightened sensitivity to this antibiotic. ΔponA1, ΔponA2, or ΔldtB cells exhibited no change in MIC when treated with SDS, and only ΔldtB cells were slightly more sensitive to isoniazid. The Δrv1086 mutant was eightfold more sensitive to teicoplanin and fourfold more sensitive to meropenem and ethambutol compared with wild-type Mtb (Fig. 5). Together, these data suggest that the enzymes that comprise distinct PG synthetic networks have different roles in antibiotic tolerance in Mtb.

Fig. 5.

Differential susceptibility of Mtb cell-wall mutants to cell-wall–active antibiotics. The fold change in MIC for the indicated drugs and SDS were calculated compared with wild-type Mtb for the indicated strains.

Discussion

Cell-wall synthesis requires the collaboration of multiple enzymes. In most bacterial species, individual PBPs are dispensable. This is generally interpreted as evidence of functional redundancy, suggesting that enzymes have overlapping functions. Clearly, this is not entirely true in both Msm and Mtb. In Msm, a single bifunctional PBP, PonA1, is essential for normal growth, but ponA1 and ponA2 are both required for robust growth of Mtb during infection. Our network analysis suggests that PonA1 and PonA2 are not identical—each is genetically associated with overlapping and, importantly, unique factors. This may suggest that although PonA1 and PonA2 mediate similar reactions, the pathways by which each synthesizes PG are different. This likely has functional consequences for bacterial growth in specific conditions. Indeed, we found that mutant cells exhibit differential survival under antibiotic treatment, suggesting that cell-wall synthesis enzymes, even closely related homologs, exhibit different functionality during Mtb growth. This is likely true for other bacterial species as well. Furthermore, we found that both ponA1 and ponA2 are genetically associated with ldtB. This suggests that the bifunctional PBPs function together with this major 3–3 transpeptidase to synthesize new PG during growth.

What do these genetic interactions mean? They may imply separate biochemical pathways that, for example, provide precursors to PonA1 and PonA2. Several pieces of evidence indicate that PonA1 and PonA2 have distinct cellular roles, including their susceptibilities to host-like stresses or infection (14) as well as structural differences (28) and different impacts on cell shape (Fig. 1) (16). These data may support a model wherein PonA1 and PonA2 exist in different subcellular complexes (3). Our genetic analyses also support different cellular roles for PonA1 and PonA2. Notably, few interactions were identical for ponA1 and ponA2, suggesting their cellular activities are not truly redundant (Fig. 6). Because a fully redundant system would unlikely be maintained through evolution, there is likely some selective advantage to having multiple independent systems for PG synthesis (in Mtb and other organisms). There could be several reasons for this. For example, these proteins could be individually regulated, either transcriptionally or by substrate availability provided by proteins lying within dedicated synthesis pathways. This could result in altered rates of PG formation and, consequently, growth, or could result in a different structure of PG. For example, loss of 4–3 cross-links could increase the importance of 3–3 cross-links for cell-wall integrity. This model is consistent with the relative importance of ldtB, one of the major 3–3 cross-linking enzymes, with loss of either ponA1 or ponA2.

Fig. 6.

ponA1, ponA2, and ldtB are hubs of distinct cell-wall synthesis networks. Selected interactions with cell-wall synthesis genes discovered in whole-genome screens (dashed lines) and/or by directed knockouts (solid lines) for ponA1, ponA2, and ldtB. The members of these networks respond differently to specific cell-wall drugs, such as teicoplanin and meropenem. For example, meropenem may target PonA1 more (thicker “T”) than LdtB (thinner “T”).

ldtB is the single Ldt that becomes critical for growth in the absence of ponA1 or ponA2 (Fig. 3). The genetic interaction between the bifunctional PBPs and ldtB suggests that these enzymes together promote new cell-wall synthesis during growth. This may indicate that new glycan strands (synthesized by PonA1 or PonA2) are predominantly first cross-linked in a 3–3 manner (for example, by LdtB). This model is supported by the prevalence of 3–3 cross-links in mycobacterial PG at all growth stages (5). Our data also show that LdtB is critical for the maintenance of normal cell shape (Fig. 1), which suggests that LdtB holds a key role in cell-wall synthesis. Such 3–3 peptide cross-links, which also exist in other bacteria, may provide increased structural integrity to the cell during adverse conditions.

Whereas the cellular changes brought about by mutation are the ends of the spectrum, it is likely that the balance between PonA1 and PonA2 activity is altered under different growth conditions. This produces bacilli that can closely adapt to particular growth conditions. For example, although there is little effect on growth rate in culture, loss of PonA1 or PonA2 results in attenuation during murine infection. This could be associated with changes in cell morphology that are observed even in culture or could be specific for interactions between the cell wall and the host.

A specific example of adaptation is the presence of antibiotics. Mutant cells have altered susceptibility to some antibiotics (Figs. 5 and 6). It is possible that this is due to altered bacterial permeability. However, these differences are mainly specific for drugs that affect the synthesis of cell-wall components and not the detergent SDS, suggesting that increased susceptibility is actually caused by changes in the requirement for specific cell-wall synthetic enzymes in the presence of mutations. The differential antibiotic response of ponA1 and ponA2 mutant cells further supports a model wherein they exist in separate PG synthesis pathways. For example, ponA2 mutant cells are more sensitive to meropenem and teicoplanin than ponA1 mutant cells. This suggests that these drugs may more efficiently inhibit the active enzymes in ΔponA2 cells (including PonA1) than the remaining enzymes in ΔponA1 cells. These observations suggest that inhibition of PG synthesis by transpeptidase inhibitors such as β-lactam or glycopeptide antibiotics could synergize with other cell-wall biosynthesis inhibitors and increase their efficacy. Understanding the pathways involved could help to design such synergistic pairs of inhibitors—for Mtb as well as other bacterial pathogens, many of which have not been subjected to similar studies. Efforts to target these pathogens could ultimately profit from similar strategies to identify novel members of key metabolic pathways and define individual contributions to antibiotic tolerance.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions.

M. tuberculosis H37Rv and E. coli Top10 (Invitrogen; used for cloning) were cultured as in ref. 16. The construction of the ΔponA1 and ΔponA1 L5::ponA1wt Mtb strains was described in ref. 16.

Transposon Mutagenesis.

The H37Rv transposon libraries were generated using the ϕMycoMarT7 phagemid as previously described (29).

Genomic Library Construction and High-Throughput Sequencing.

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was harvested from the transposon libraries and prepared for PCR amplification as described (19). PCR-amplified transposon–gDNA junctions were then subjected to high-throughput sequencing (Illumina). For additional details of library preparation and data analysis, see SI Materials and Methods.

Mapping and Counting Transposon Insertions.

Sequence data were filtered for transposon-specific information and trimmed of transposon sequence except for the TA dinucleotide insertion site with custom Python scripts (SI Appendix, sections 1, 2, and 3). Trimmed reads were mapped to the H37Rv genome using Bowtie2 (30). Insertions at each genomic TA site were counted with custom Python scripts (SI Appendix, sections 4 and 5).

Analysis of Differentially Inserted Genes.

Loci that were differentially disrupted between wild-type and mutant cells were assessed as in ref. 22 (Dataset S1). We used the Mann–Whitney u test and simulation-based normalization without the hidden Markov model (HMM) (22). For each library’s locus, the geometric mean of the sequence reads was calculated (Dataset S2) with a custom MATLAB script using the encoded geomean function (SI Appendix, section 10).

Recombinant DNA Constructs and Gene Knockouts.

ponA1 was subcloned into the L5 pMC1s vector as in ref. 16. The ponA2 knockout cassette was amplified by PCR from a custom phage (31). The rv1086 and ldtB knockout cassettes consisted of 500 nucleotides 5′ or 3′ of rv1086 or ldtB flanking a hygromycin cassette with PmeI sites at each end (Gen9). Digestion with PmeI (New England Biolabs) generated linear recombineering products. The ponA2, ldtB, and rv1086 deletions were generated in the ΔponA1 L5::ponA1wt strain (16) via recombineering (for more details, see SI Materials and Methods).

Allelic Exchange in Mtb.

Allelic exchange occurs as described (16, 23). The ΔponA1 L5::ponA1wt loxed strain wherein ponA2, rv1086, or ldtB was deleted was used for allelic exchange. Simultaneous control transformations with the same L5 vectors were performed in ΔponA2, Δrv1086, and ΔldtB cells. Colony-forming units were counted at 21 d, except for the ΔponA1 L5::tetR ΔldtB plate, which was counted at 35 d.

Optical Density Measurements.

Population growth curves for Mtb strains were performed as in ref. 16.

Light Microscopy and Image Analysis.

Cells were fixed overnight in 1% formalin at 4 °C in the Biosafety Level 3 facility. Cells were imaged and morphology analyzed as in ref. 16. Final images were prepared in Fiji (32).

Antibiotic MIC Assays.

The antibacterial effects of meropenem, teicoplanin, ethambutol, isoniazid, and SDS (Sigma Aldrich) were determined as in ref. 16.

Data Representation and Statistical Analysis.

Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software) was used to graph and analyze numerical data. Statistical tests in Prism calculated significance of measurements as reported in figure legends. The Venn diagram was generated with BioVenn (33). Transposon insertions were visualized in DNAplotter (34) or Artemis (35) by converting the insertion counts to appropriate data structures with custom Python scripts (SI Appendix, sections 8 and 9).

SI Materials and Methods

Transposon Library Preparation.

About 100,000 colonies were collected for each of the transposon libraries. A single replicate library was constructed for each strain and used in downstream analyses.

Mapping and Counting Transposon Insertions.

For the ΔponA1 library, a FASTQ file was generated from the raw sequencing data using a custom Python script (SI Appendix, section 1) (all other libraries were sequenced on Illumina machines that automatically generated FASTQ files). The ΔponA1 library had 3.2 million mapped reads with an average read count of 50. The ΔponA2 library had 2.4 million mapped reads with an average read count of 37. The ΔldtB library had 1.3 million mapped reads with an average read count of 20. The wild-type Mtb library had 4.4 million mapped reads with an average read count of 69 (Fig. S2A).

To count transposon insertions, the genomic location of all TA dinucleotides was first mapped (the H37Rv FASTA sequence was downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information; SI Appendix, section 4). The mapped transposon insertions were then counted at each TA site and associated with their appropriate genetic feature using an H37Rv gene list that was downloaded from the J. Craig Venter Institute (SI Appendix, section 5).

Assessment of Library Saturation.

The complexity of the libraries was assessed at the genome scale by calculating the number of TA sites in the genome that contained a transposon insertion (SI Appendix, section 6). The ΔponA1 library had 54% of the genome’s TA sites disrupted. The ΔponA2 library had 57% disruption. The ΔldtB library had 42% disruption, and wild type had 54% disruption. To gain a gene-level resolution of transposon disruption, the fraction of disrupted TA sites per gene was calculated as previously described (21) using a custom Python script (SI Appendix, section 7) and Excel functions. The middle of the right-hand peak (Fig. S2B) can be used to estimate the true saturation of the libraries (because insertions in essential genes cannot be sequenced because the bacteria are not viable, calculating the genome’s percent TA disruption is an underestimate of true saturation).

Analysis of Differentially Inserted Genes.

We did not use the HMM because HMMs are robust for sequentially selected libraries but are less robust for the analysis of independently generated libraries (e.g., different strain backgrounds). We performed 100 simulations and asked for loci that were statistically significantly different from wild type (P value < 0.001) in at least 90 of the 100 simulations.

Construction of Gene Knockouts in Mtb.

A hygromycin resistance cassette flanked with LoxP sites marked the ponA1 deletion in the ΔponA1 L5::ponA1wt strain. The hygromycin cassette was removed by transforming the strain with Cre recombinase (containing a counterselectable sucrose marker). Several hygromycin sensitive clones were counterselected on sucrose. This strain is still referred to as ΔponA1 L5::ponA1wt throughout the text. This loxed strain was then transformed with a gentamicin-resistant RecE/T plasmid for recombineering. After recombineering, cells were recovered 24 h in nonselective 7H9 and then plated on selective 7H10. Positive recombinants were identified by multiple PCR reactions: the appropriate genomic position of the 5′ and 3′ recombineering construct and the absence of wild-type 5′ and 3′ sequence at those junctures. Such clones were then screened for the absence of the gene of interest to verify that a gene duplication had not occurred. Wild-type H37Rv was used as a control in all PCR reactions. PCR screening was performed with GoTaq polymerase (Promega) or KOD Xtreme Hot Start DNA polymerase (EMD Millipore).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the E.J.R. and Fortune laboratories for thoughtful discussions and technical expertise and M. Larsen for the phage encoding the ponA2 knockout cassette. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants U19 AI107774 (to E.J.R., T.R.I., C.M.S., and J.C.S.), U01 GM094568 (to E.J.R.), F32 GM108355-02 (to M.C.C.), and F32 A1093049 (to J.E.L.), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (C.M.S. and M.K.W.), and a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (Grants DGE1144152 and DGE0946799 to K.J.K.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1514135112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Global Tuberculosis Report. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kieser KJ, Rubin EJ. How sisters grow apart: Mycobacterial growth and division. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12(8):550–562. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Typas A, Banzhaf M, Gross CA, Vollmer W. From the regulation of peptidoglycan synthesis to bacterial growth and morphology. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10(2):123–136. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lavollay M, et al. The peptidoglycan of stationary-phase Mycobacterium tuberculosis predominantly contains cross-links generated by L,D-transpeptidation. J Bacteriol. 2008;190(12):4360–4366. doi: 10.1128/JB.00239-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar P, et al. Meropenem inhibits D,D-carboxypeptidase activity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol. 2012;86(2):367–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dubée V, et al. Inactivation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis l,d-transpeptidase LdtMt1 by carbapenems and cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56(8):4189–4195. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00665-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wivagg CN, Bhattacharyya RP, Hung DT. Mechanisms of β-lactam killing and resistance in the context of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2014;67(9):645–654. doi: 10.1038/ja.2014.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole ST, et al. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393(6685):537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dasgupta A, Datta P, Kundu M, Basu J. The serine/threonine kinase PknB of Mycobacterium tuberculosis phosphorylates PBPA, a penicillin-binding protein required for cell division. Microbiology. 2006;152(Pt 2):493–504. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28630-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hugonnet J-E, Tremblay LW, Boshoff HI, Barry CE, 3rd, Blanchard JS. Meropenem-clavulanate is effective against extensively drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 2009;323(5918):1215–1218. doi: 10.1126/science.1167498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanders AN, Wright LF, Pavelka MS., Jr Genetic characterization of mycobacterial L,D-transpeptidases. Microbiology. 2014;160(Pt 8):1795–1806. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.078980-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta R, et al. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein LdtMt2 is a nonclassical transpeptidase required for virulence and resistance to amoxicillin. Nat Med. 2010;16(4):466–469. doi: 10.1038/nm.2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schoonmaker MK, Bishai WR, Lamichhane G. Nonclassical transpeptidases of Mycobacterium tuberculosis alter cell size, morphology, the cytosolic matrix, protein localization, virulence, and resistance to β-lactams. J Bacteriol. 2014;196(7):1394–1402. doi: 10.1128/JB.01396-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patru MM, Pavelka MS., Jr A role for the class A penicillin-binding protein PonA2 in the survival of Mycobacterium smegmatis under conditions of nonreplication. J Bacteriol. 2010;192(12):3043–3054. doi: 10.1128/JB.00025-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hett EC, Chao MC, Rubin EJ. Interaction and modulation of two antagonistic cell wall enzymes of mycobacteria. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(7):e1001020. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kieser KJ, et al. Phosphorylation of the peptidoglycan synthase PonA1 governs the rate of polar elongation in mycobacteria. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(6):e1005010. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vandal OH, Pierini LM, Schnappinger D, Nathan CF, Ehrt S. A membrane protein preserves intrabacterial pH in intraphagosomal Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat Med. 2008;14(8):849–854. doi: 10.1038/nmXXXX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vandal OH, et al. Acid-susceptible mutants of Mycobacterium tuberculosis share hypersusceptibility to cell wall and oxidative stress and to the host environment. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(2):625–631. doi: 10.1128/JB.00932-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Long JE, et al. Identifying essential genes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by global phenotypic profiling. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1279:79–95. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2398-4_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joshi SM, et al. Characterization of mycobacterial virulence genes through genetic interaction mapping. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(31):11760–11765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603179103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chao MC, et al. High-resolution definition of the Vibrio cholerae essential gene set with hidden Markov model-based analyses of transposon-insertion sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(19):9033–9048. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pritchard JR, et al. ARTIST: High-resolution genome-wide assessment of fitness using transposon-insertion sequencing. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(11):e1004782. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blasco B, et al. Virulence regulator EspR of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a nucleoid-associated protein. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(3):e1002621. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parthasarathy G, et al. Rv2190c, an NlpC/P60 family protein, is required for full virulence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43429. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pashley CA, Parish T. Efficient switching of mycobacteriophage L5-based integrating plasmids in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2003;229(2):211–215. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00823-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schulbach MC, et al. Purification, enzymatic characterization, and inhibition of the Z-farnesyl diphosphate synthase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(15):11624–11630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007168200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong SD, et al. The structural basis for induction of VanB resistance. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124(31):9064–9065. doi: 10.1021/ja026342h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calvanese L, et al. Structural and binding properties of the PASTA domain of PonA2, a key penicillin binding protein from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biopolymers. 2014;101(7):712–719. doi: 10.1002/bip.22447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sassetti CM, Boyd DH, Rubin EJ. Comprehensive identification of conditionally essential genes in mycobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(22):12712–12717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231275498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9(4):357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jain P, et al. Specialized transduction designed for precise high-throughput unmarked deletions in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. MBio. 2014;5(3):e01245–e14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01245-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schindelin J, et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9(7):676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hulsen T, de Vlieg J, Alkema W. BioVenn - a web application for the comparison and visualization of biological lists using area-proportional Venn diagrams. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:488. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carver T, Thomson N, Bleasby A, Berriman M, Parkhill J. DNAPlotter: Circular and linear interactive genome visualization. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(1):119–120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carver T, Harris SR, Berriman M, Parkhill J, McQuillan JA. Artemis: An integrated platform for visualization and analysis of high-throughput sequence-based experimental data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(4):464–469. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.