Abstract

Objective:

To present the conceptual foundations that explain how events occurring during intrauterine life may influence body development, emphasizing the interrelation between low birth weight and risk of obesity throughout life.

Data sources:

Google Scholar, Library Scientific Electronic Online (SciELO), EBSCO, Scopus, and PubMed were the databases. “Catch-up growth”, “life course health”, “disease”, “child”, “development”, “early life”, “perinatal programming”, “epigenetics”, “breastfeeding”, “small baby syndrome”, “phenotype”, “micronutrients”, “maternal nutrition”, “obesity”, and “adolescence” were isolated or associated keywords for locating reviews and epidemiological, intervention and experimental studies published between 1934 and 2014, with complete texts in Portuguese and English. Duplicate articles, editorials and reviews were excluded, as well as approaches of diseases different from obesity.

Data synthesis:

Within 47 selected articles among 538 eligible ones, the thrifty phenotype hypothesis, the epigenetic mechanisms and the development plasticity were identified as fundamental factors to explain the mechanisms involved in health and disease throughout life. They admit the possibility that both cardiometabolic events and obesity originate from intrauterine nutritional deficiency, which, associated with a food supply that is excessive to the metabolic needs of the organism in early life stages, causes endocrine changes. However, there may be phenotypic reprogramming for low birth weight newborns from adequate nutritional supply, thus overcoming a restrictive intrauterine environment. Therefore, catch-up growth may indicate recovery from intrauterine constraint, which is associated with short-term benefits or harms in adulthood.

Conclusions:

Depending on the nutritional adequacy in the first years of life, developmental plasticity may lead to phenotype reprogramming and reduce the risk of obesity.

Keywords: Human development, Low birth weight, Nutrition, Obesity, Health, Disease

Introduction

The knowledge of the processes involved in human development contributes to the better understanding of the mechanisms associated with health and disease throughout life.1 To identify these mechanisms, when and how they work is probably the best way to prevent the disease onset. Only in recent years several diseases that affect adults have been associated with intrauterine period events.2 - 4

Although complementary examinations provide information that allows fetal development monitoring, obtaining data at birth provides better conditions for assessment, with adequacy of weight for gestational age being the first measurement capable of providing information on fetal interaction with the intrauterine environment.5

The fetus reflects, through nutrition, growth and body composition, the supplies and the energy it receives from the mother, also expressing its dependence on placental function.6 The fetus also receives a flow of chemical mediators, which inform about the maternal nutritional status and possibly the quality of the postnatal environment.3 This information contributes to define body composition and size, as well as to structure the endocrine and metabolic systems.7

The United Nations Children's Fund8 reports that the worldwide incidence of low birth weight remained at 15% in the period of 2008-2012, despite the advances in prenatal care. The World Health Organization9 confirms that more than 40 million children younger than 5 years are overweight or obese and, therefore, are susceptible to an increased risk of noncommunicable diseases. These statistics reinforce the importance of considering the interrelations between low birth weight and the risk of obesity and its comorbidities throughout life, considering that this understanding is the basis to establish early interventions that can change the natural history of this process.

This review aimed to disclose the conceptual and empirical foundations underlying the understanding of the effect of intrauterine life events on body development, emphasizing the interrelation between low birth weight and obesity throughout life.

Method

A narrative review was performed, using the descriptors “catch-up growth”, “life course health”, “disease”, “child”, “development”, “human evolution”, “adaptive”, “infant”, “early life”, “birth”, “weight”, “perinatal programming”, “epigenetics”, “breastfeeding”, “small baby syndrome”, “phenotype”, “micronutrients”, “maternal nutrition”, “fetus”, “obesity”, and “adolescence”, alone or in association with others, in the Google Scholar, Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO), EBSCO, Scopus and PubMed databases, to identify published articles.

Inclusion criteria comprised review articles, epidemiological, experimental or intervention studies published between 1934 and 2014, with full texts in Portuguese or English, addressing aspects of intrauterine development and its association with obesity. Abstracts or articles published in duplicate were excluded, as well as those addressing diagnosis or treatment of specific diseases rather than obesity, editorials and reviews.

Abstracts that met the inclusion criteria were reviewed by two independent reviewers who had knowledge of the central theme of the review, to attain consensual definition of the articles that would be read in full.

Results

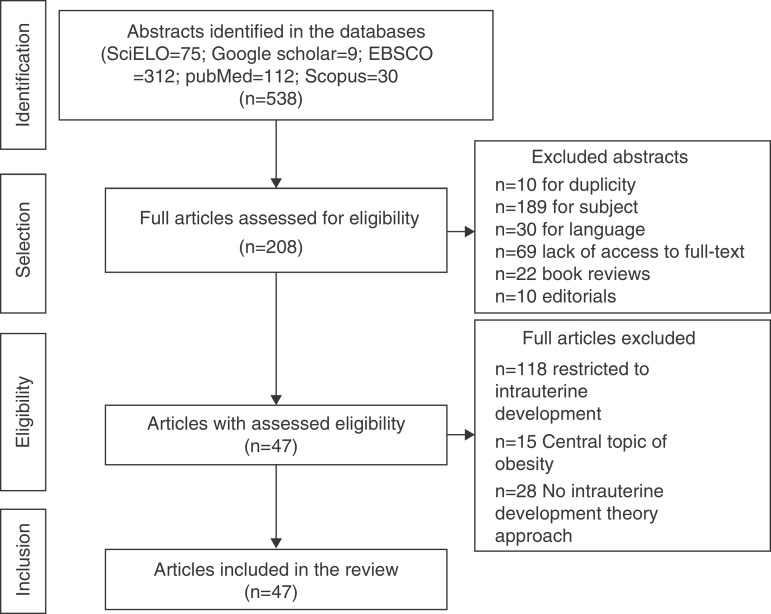

A total of 538 abstracts were found, of which 330 were excluded, resulting in the analysis of the full texts of 208 articles. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the sample comprised 47 eligible articles that were included in the review (Fig. 1) and which were used to prepare the glossary described in Table 1.

Figure 1. Flowchart of article selection for the review.

Table 1. Glossary of terms and concepts used in this review.

| Terms | Concepts |

|---|---|

| Catch-up growth | Period of rapid weight gain and/or acceleration in growth rate that occurs after a slowdown period |

| Epigenetics | Study of alterations in gene expression that can be transmitted to offspring and do not imply in DNA sequence alterations |

| Thrifty phenotype hypothesis | When the fetal environment is poor from a nutritional point of view, the fetal body goes through a programming process in which there is protection for the development of some organs (brain, heart); however, it leads to metabolic changes that may impact on later stages of life |

| Phenotypic plasticity | The capacity of the organism to develop several phenotypes from a single genotype, in response to different environmental stimuli |

| Fetal programming | Structural and functional changes that occur in the fetal body in response to stimuli that occur at critical periods of development |

| Predictive adaptive responses | A process through which the body, in the early stages of development, predicts the environment it will be exposed to in the future by modifying itself phenotypically, based on the perception of environmental stimuli |

First evidence and the thrifty phenotype hypothesis

The influence of factors present in early life was identified in reports that analyzed the mortality rate from all causes in the UK and Sweden, from 1845 to 1925, at the age range of 10-100 years, which originated the hypothesis that a change in the environment could help reduce mortality.10 , 11Failure to prove the hypothesis motivated the inclusion of the age group 5-10 years in the mortality study. This time, an association was observed between improvement in living conditions of children and adolescents and decrease in overall mortality rate in both countries, suggesting that the improvement of environmental conditions during pregnancy could have a direct effect on the health of children in the younger age groups.11

Studies carried out in equines12demonstrated the influence of the maternal body on the fetus, regardless of the genetic factor. Fetuses of large animals implanted in the uterus of small species resulted in foals that were smaller than expected, as well as fetuses generated in small equines showed greater development when implanted in large mares.

In the context of these ideas, Neel13published observations on the effects of maternal nutritional deprivation on the fetus. The author theorized that fetuses developed a type of metabolism aimed at conserving energy, with insulin resistance being important, which would be related to a random genetic mutation.13 The preponderance of this “thrifty genotype” would last and would be passed on to future generations, and thus, the abundant consumption of food would lead to obesity by excessive accumulation of reserves.

The effect of food shortages during the German siege of the Netherlands in World War II14 made women suffer the impact of malnutrition during pregnancy. The analysis of this natural experiment raised questions about Neel's hypothesis,13 as nutrient deprivation led to different effects than those expected. Fetuses that suffered malnutrition in the first trimester developed obesity in adulthood, while nutritional restriction after the initial phase of pregnancy was not associated with the same effect. Even if one would admit the importance of environmental stimuli in the occurrence of obesity, the genetic factor could not be ignored.

A Norwegian study15 reinforced the importance of nutritional status in childhood in the genesis of adult diseases. Considering the generation of individuals born between 1896 and 1925, it was verified that increased mortality in adults occurred in counties with higher infant mortality, with risk factors being increased blood cholesterol and a high-fat diet consumption, as well as individuals' social status, smoking and type of nutrition. Regarding the contribution of the high-fat diet to high cholesterol levels, the study identified different behaviors according to the socioeconomic status of individuals. The ones who had previously experienced poverty had increased cholesterol related to a high-fat diet, which did not occur with those with a financially stable life.15 These findings provided the basis for the hypothesis that the deprivation period contributed for individuals to develop “fat intolerance”, being exposed to a higher risk of death when they received an abundant diet.

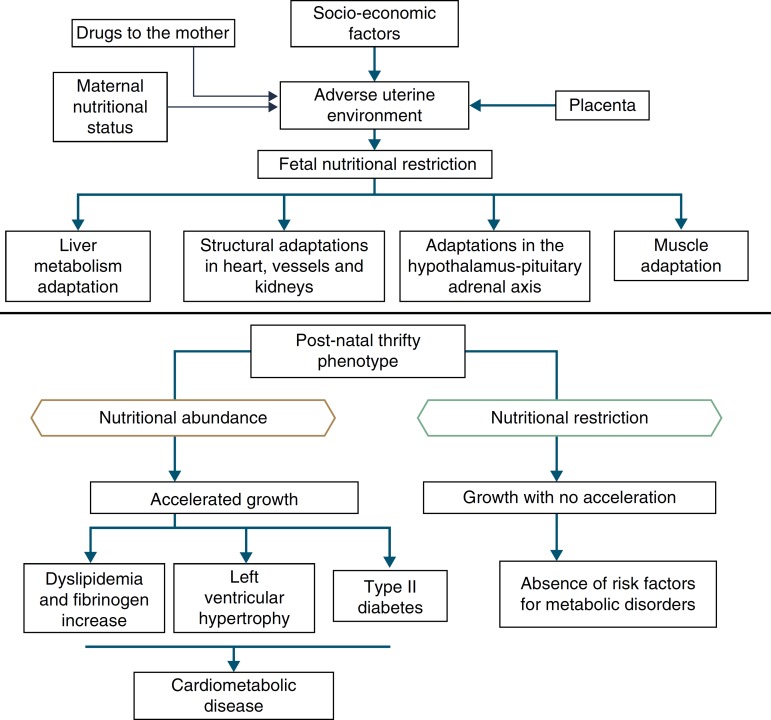

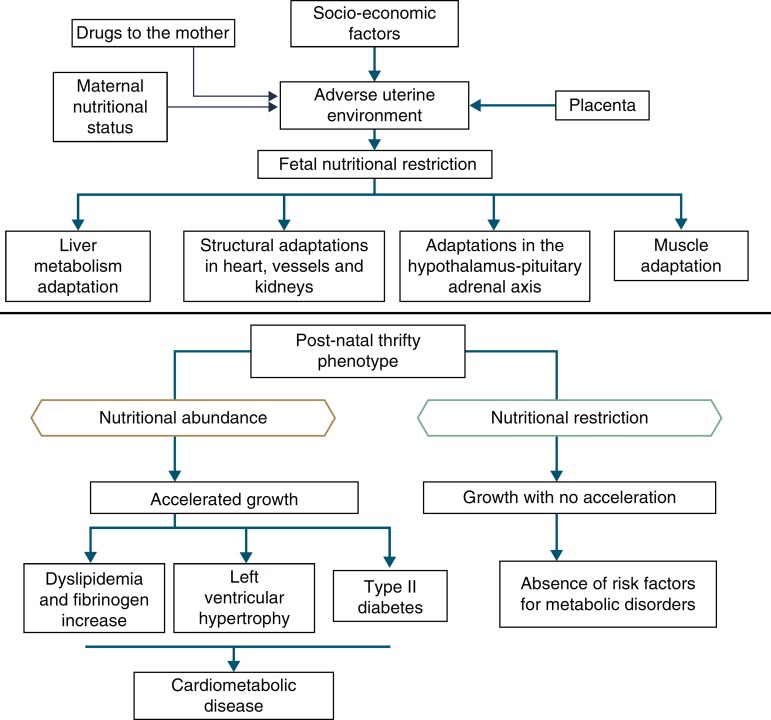

In addition to the hypotheses of fat intolerance and the “thrifty genotype”, a cohort in Hertfordshire16 , 17 demonstrated an association between low birth weight and death from coronary heart disease in adulthood. Risk factors for cardiovascular and metabolic diseases were more frequent among those born with low birth weight.17 Additionally, Barker16 proposed that the fetus responds with growth retardation when there is a nutrient deficit in its environment, which is associated with decreased insulin sensitivity, providing better survival circumstances. This adaptation also predicts, in adult life, maintenance of an environment with low supply of nutrients. If this situation does not occur, the abundant supply of food creates an imbalance that can lead to cardiometabolic diseases. This context led to the thrifty phenotype hypothesis,16 and subsequently, to the predictive adaptive response,3 which are depicted in Fig. 2.

Figure 2. The thrifty phenotype hypothesis and predictive adaptive response.

Situations related to birth weight alterations reinforce its importance as an indicative marker of intrauterine environment and predictor of cardiometabolic diseases in adolescence and adulthood.18 - 20 Thus, birth weight may have a constitutional origin or be secondary to intrauterine nutritional deprivation, which leads to fetal growth restriction. It is acknowledged that low birth weight newborns undergo the influence of different mechanisms of adaptation to extra-uterine environment, among which are the increase in carbohydrate metabolism and the consequent increase in adiposity, increasing the future risk of chronic diseases such as insulin resistance, obesity and type 2 diabetes.19 These mechanisms lead to high levels of leptin, secondary to increased resistance level of its receptors, related to lack of satiety in early life, which is associated with obesity and metabolic disorders in adolescence and adulthood, when these newborns are exposed to a nutritional environment with excessive nutritional offer in the early years of life.20

When leaving this situation of restricted growth, due to hormonal or nutritional issues, to another with adequate supply of nutrients, accelerated growth recovery may occur to achieve the genetically determined potential,21 which is the so-called catch-up growth.22

Catch-up growth can be defined as the rate of weight gain and/or growth that is higher than the statistical limits of normality for age and maturity that occurs during a defined period of time, following a transient period of growth inhibition.21 Catch-up growth is a physiological process related to size recovery of a body subjected to restriction, so that it can reach the adequate size for age, gender and degree of maturity, depending on the action of the somatotropic axis, with an increase in hormone receptors.21

This recovery, resulting from unfavorable conditions for growth during the prenatal and early postnatal periods, can influence the risk of developing cardiometabolic diseases throughout life.23 , 24 However, short-term growth recovery offers advantages for neurodevelopment, particularly for children born with very low birth weight, and also contributes to increased resistance to infections. Hence the question of identifying whether the benefits of increased growth velocity can occur without adverse metabolic consequences.18

It is accepted that a catch-up growth >0.67 standard deviations would be associated with central obesity25 and trigger insulin resistance, which leads to a compensatory increase in insulin secretion, even in low birth weight newborns that showed increased growth rate, but remain small during childhood. Even if these children show an increase in growth rate, they have compensatory hyperinsulinemia to a greater degree than well-nourished children or the ones who are excessively fed. Thus, hyperinsulinemia secondary to insulin resistance could be the key explanation for the genesis of metabolic syndrome.26

Insulin resistance in preterm infants is associated with hypersecretion of growth hormone and reduced levels of IGF-1, which persist for 3 months after birth in the absence of adequate nutritional supply. This altered endocrine status favors reduction of subcutaneous adipose tissue, with relative visceral adiposity, a marker of insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and the presence of other metabolic syndrome components.27

Despite these observations, it is not clear whether central obesity, rather than subcutaneous fat, is a function of prematurity, of being born small for gestational age or of catch-up growth. Studies have shown that infants with growth restriction at birth have reduced subcutaneous fat, but maintain levels of abdominal fat similar to those of newborns that are adequate for gestational age.28 A cohort study carried out to investigate the association between fetal and early postnatal growth and metabolic and anthropometric alterations showed that catch-up growth was associated with the fetal growth pattern, regardless of birth weight, and was related to higher insulin sensitivity and lower concentrations of leptin at birth. Therefore, the catch-up growth would promote the recovery of body size and fat stores without deleterious consequences to the metabolic profile and body composition, after one year of age.29

A recent review30 was performed to search evidence on the association between low weight, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes in adults, considering body composition and metabolic pathways. The empirical basis shows a multifactorial association and points out that, in some children and adults who were born preterm, insulin resistance and increased abdominal adiposity originate from the variation of the glucocorticoid receptor gene. Higher concentrations of glucocorticoids activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, promoting the intake of palatable foods, which activate the pleasure centers of the brain and trigger greater accumulation of adipocytes. Thus, adults who were born preterm may have increased sensitivity to stressors, leading to an overproduction of glucocorticoids, stimulating the omental population of pre-adipocytes, with increased abdominal fat deposition.

Experimental studies have brought new ideas to explain the origin of adult diseases in early life, but raised new questions. The hypotheses did not contribute to the understanding about the occurrence of these diseases in individuals born large for gestational age, as well as in fetuses with adequate weight that developed them in adulthood. Moreover, they did not explain how fetuses with intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), with decreased insulin sensitivity in early postnatal life, developed increased resistance only in adult life, which seems to indicate loss of the metabolic process continuum, as if the latter had started only in adulthood.

To analyze the association between low birth weight and hypertension development in adulthood, Huxley et al.,31 in a meta-analysis, compared 18 articles submitted by researchers that corroborated the thrifty phenotype hypothesis with 37 studies from other researchers. Although this meta-analysis31 did not show an association between low birth weight and hypertension in adults, it did not rule out the adaptive hypotheses, and other aspects of late expression of intrauterine life determinants started to be investigated. The hypotheses were based on the idea of conservation, which did not seem to represent the overall process. Observations from the beginning of life suggested a much wider and widespread phenomenon, in which the pattern of development could be modified in any direction, depending on the stimulus.32 , 33

The epigenetic explanation, the thrifty phenotype and cardiometabolic diseases

Based on the possibility that the phenotype can generate different genotype under different environmental conditions, that is, phenotypic plasticity, Gluckman et al.34 enunciated the hypothesis of an “adaptive predictive response” to the environment. The development plasticity would be evoked by environmental alterations early in life, generating an adaptive phenotypic response, of which advantages would manifest only in later stages. Therefore, the phenotypic plasticity might have granted advantages to the human species to face environments with nutritional restriction or high-energy expenditure. However, when submitted to a different nutritional environment than the programmed one, individuals would have exacerbated responses and develop diseases in adulthood.34 The “predictive adaptive response” will be an adaptive advantage when the “prediction” about the environment is correct (match) and may determine a disadvantage when it is wrong (mismatch),34 characterizing plasticity.

Plasticity can trigger different responses with immediate expression, such as nutritional restrictions to the fetus, which reacts with a decrease in its nutritional reserves, decreased anabolism, plasma insulin, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), and blood flow diversion to protect the heart and brain. These immediate adaptations to the restrictive environment allow adequate survival, but result in low birth weight, increased risk of morbidity and mortality, cognitive impairment, and persistent growth deficit.35

Responses aimed at ensuring survival can, however, lead to adaptive errors. Maternal hyperglycemia in early pregnancy can contribute to embryopathy, by leading to the reduction of myo-inositol, which is essential for embryonic development during gastrulation and the neurulation stages. Myo-inositol deficiency seems to disturb the phosphoinositide system, which leads to abnormalities in the arachidonic acid-prostaglandin pathways and increase in reactive oxygen substances.36 This chain of events is responsible for fetal cardiovascular abnormalities, such as transposition of the great vessels, ventricular septal defects, hypoplastic left heart syndrome, and dextrocardia.37Increased maternal glycated hemoglobin is associated with embryonic alterations in 66% of fetuses, but when lower than 9.5%, it does not alter embryogenesis,36 characterizing disruption,3 in which a hormone can trigger an undesirable effect on the response process to environmental adaptation.

Although the fetal and postnatal organisms have adaptive responses to a restrictive intrauterine environment in a continuous manner, their development has “plasticity windows”, i.e., the possibility of interference with the adaptive programming, correcting inappropriate responses.38 This hypothesis is corroborated by an experimental study comparing offspring with growth retardation, born to malnourished rats during pregnancy, to the offspring of well-nourished rats, after feeding a hypercaloric diet to the offspring without IUGR and leptin to those with IUGR. The authors verified that growth in the two groups did not differ and concluded that the increase in leptin concentration signaled the presence of an adequate amount of adipose tissue in the offspring organism and, therefore, of nutritional reserves.38

The adaptive continuity to environmental changes and “windows of opportunity” are explained by the epigenetic theory, i.e., the possibility that environmental factors interfere with gene expression. Predictive adaptive responses are modulated by covalent modifications of deoxyribonucleic acid and histones, which are necessary for the phenomenon of gene transcription, namely the synthesis of ribonucleic acid for protein synthesis.39

Evidence suggests that the fetal period is more sensitive for the occurrence of epigenetic variations that will influence cell and tissue genetic expression, sexual dimorphism and the risk of triggering disorders that will manifest later in life.40 An example of the influence of epigenetics on the early neonatal period is the effect of high-fat diets during pregnancy,41 i.e., overeating in the offspring and increased expression of orexigenic peptides promoting increase and deregulation of neonatal leptin.

The deregulation is important, because leptin is one of the first hormones synthesized during embryonic development by the placenta, by adipocytes of white adipose tissue, liver cells, cartilaginous structures and heart muscle. This molecule acts on neurogenesis, axonal growth, dendritic proliferation, synapse formation,23 in the development of neurological pathways to satiety, hunger and thermal regulation, which begins in intrauterine life and is completed in the first months of life, when supplied by breast milk.42

During the first pregnancy trimester, leptin synthesis occurs in the placenta, triggering a cascade of transcription factors in pre-adipocytes, contributing to the formation of white adipose tissue, which becomes the main source of leptin synthesis. This molecule, by crossing the blood-brain barrier, contributes to the development of several brain regions, among them the hypothalamus, where their receptors are located.23 The leptin-receptor binding is essential to indicate the need for nutrient intake and the increase in energy reserves in adipose tissue. When leptin concentrations in the hypothalamus are reduced due to binding to the receptors, the feeling of satiety is triggered by the activation of anorexigenic neurons. Thus, the phenotypic alteration of leptin receptors, characterizing leptin resistance, results in the persistence of the feeling of hunger and promotes ingestion of large quantities of nutrients and adipose tissue hypertrophy.24

The epigenesis of leptin resistance explains the increased risk of obesity in children of obese and diabetic mothers, as well as in newborns with IUGR submitted to excess nutrient intake or whose mothers were fed lipid-rich diets. In contrast, when during pregnancy and lactation, the mothers receive balanced diets, or when fetuses with IUGR are submitted to restrictive diets during the lactation period, they show normal growth of the adipose tissue, but develop post-weaning hyperphagia, attributed to phosphorylation deregulation of hypothalamic leptin receptors, reduction in anorexigenic receptors and reduction in permeability of the blood-brain barrier to this molecule.24

Epidemiological research18 has corroborated the hypothesis of adaptive predictive response,33 by demonstrating that an abundant food supply contributes to catch-up growth. However, it is also confirmed when there is absence of abdominal obesity, with normal neurodevelopment, in children receiving adequate nutrition, but not in excess. The significance of the nutrition of the newborn has been debated,43 especially for preterm ones, because there is more organic plasticity early in life. Thus, adequate interventions shortly after birth have plasticity as the possibility for correction of developmental delay, maintaining the benefits by cumulative effect. As age increases, with the decline in plasticity, nutrition that is adequate to the body's need will make the child's body composition reach the level of a child born to term, at the same age. Similarly, excess nutrition, also due to plasticity, will result in deleterious effects that will manifest throughout life.

One must consider4 the processes by which the quantity and quality of nutrients supplied to the fetus and the embryo are determined, due to their permanent effects on development, a process called nutritional programming, which depends on both maternal characteristics (before, during and after pregnancy), and fetal nutritional status.

Among the maternal and environmental characteristics that affect the fetal and newborn development are the socioeconomic and nutritional statuses, with direct effect, and maternal education, with an indirect effect. Nepalese infants born with low birth weight more frequently had mothers with low or very low socioeconomic level, low educational level and inadequate nutrition, factors that were associated with lower level of prenatal medical care.44 A population-based cohort followed between 1961 and 2000 disclosed that, in four decades, in the United Kingdom, socioeconomic inequalities still determined a higher frequency of low birth weight or premature births among mothers from the lower socioeconomic classes, even after adjusting for maternal age.44

Among the demographic and social factors are the maternal variables, such as age extremes (<20 and >30 years), low educational level, parity, short interbirth interval, drug use,45 and short stature.46 Breastfeeding is also considered, given its weak to moderate protective effect on adult obesity. Breastfeeding, by meeting the newborn's needs, reduces the risk of insulin resistance and increased intra-abdominal adiposity, and provides leptin concentrations capable of modulating the hunger-satiety mechanism.47

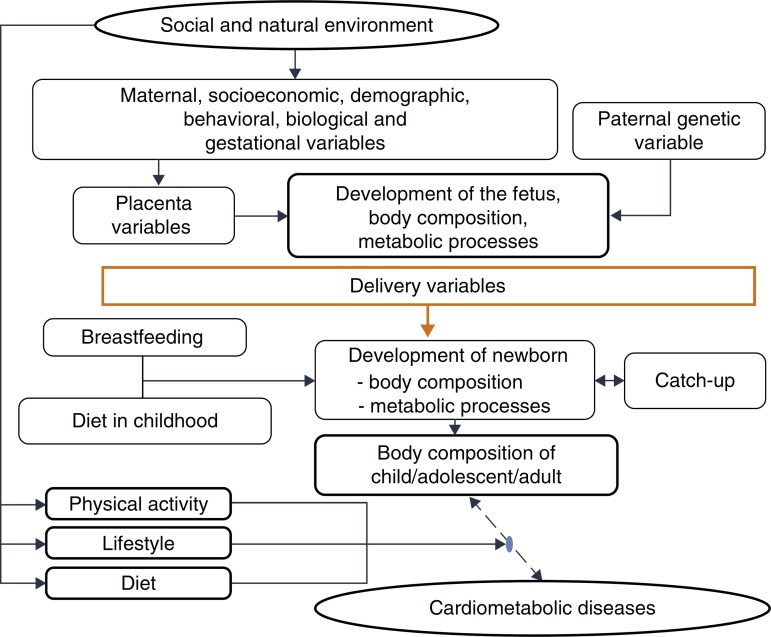

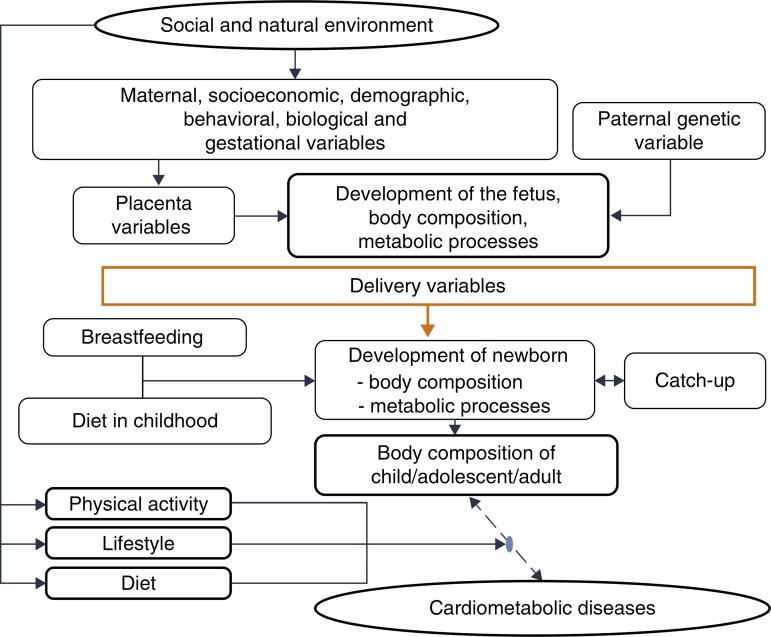

This evidence is consistent with the hypothesis accepted by Gluckman et al.,3 which affirms that nature directs its efforts to reproduction. Thus, if there are signs of a threatening postnatal environment, the fetus is born prematurely or smaller than expected, and in a nutrient-rich environment, unlike the planned trajectory, develops metabolic disease, in a multifactorial process in which many maternal and fetal factors interact (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Explanatory model – cardiometabolic diseases.

Currently, a large number of experimental, epidemiological and clinical studies that provide a robust empirical basis contribute to a paradigm change in relation to the understanding of early origin of diseases. All this knowledge has a direct effect on the training of health care professionals, particularly, in medical training. It shows the need for apprehending several aspects of biological knowledge, especially of the evolution theory, because it is through this view that one can capture the importance of the interaction between genotype and the environment and the several mechanisms used by the body to adapt to the environment. Physicians, especially pediatricians, have a key role in this scenario, as they care for human beings at a time when there are more opportunities to act and generate changes, due to developmental plasticity.

Footnotes

Funding

Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), for funding productivity grants given to Pedro Lira, Marília Lima and Giselia Alves.

Referências

- 1.Halfon N, Larson K, Lu M, Tullis E, Russ S. Lifecourse health development: past, present, and future. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18:344–365. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1346-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Cooper C, Thornburg KL. Effect of in utero and early-life conditions on adult health and disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:61–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0708473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Beedle AS. Early life events and their consequences for later disease: a life history and evolutionary perspective. Am J Hum Biol. 2007;19:1–19. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desai M, Ross MG. Fetal programming of adipose tissue: effects of intrauterine growth restriction and maternal obesity/high-fat diet. Semin Reprod Med. 2011;29:237–245. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1275517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Departamento de Análise de Situação em Saúde . Saúde Brasil 2006: uma análise da situação de saúde no Brasil. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suhag A, Berghella V. Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR): etiology and diagnosis. Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep. 2013;2:102–111. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Symonds ME, Mendez MA, Meltzer HM, Koletzko B, Godfrey K, Forsyth S, et al. Early life nutritional programming of obesity: mother-child cohort studies. Ann Nutr Metab. 2013;62:137–145. doi: 10.1159/000345598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Unicef Low birthweight. [19 de julho de 2014]. página na Internet. Disponível em: http://www.data.unicef.org/nutrition/low-birthweight.

- 9.World Health Organization Obesity and overweight. [19 de julho de 2014]. página na Internet. Disponível em: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/

- 10.Kermack WO, McKendrick AG, McKinlay PL. Death-rates in Great Britain and Sweden: some general regularities and their significance. Lancet. 1934;31:698–703. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.4.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kermack WO, McKendrick AG, McKinlay PL. Death-rates in Great Britain and Sweden: expression of specific mortality rates as products of two factors, and some consequences thereof. J Hyg (Lond) 1934;4:433–457. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400043230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walton A, Hammond J. The maternal effects on growth and conformation in shire horse-shetland pony crosses. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1938;125:311–335. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neel JV. Diabetes mellitus: a thrifty genotype rendered detrimental by progress? Am J Hum Genet. 1962;14:353–362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lumey LH, Poppel FW Van. The Dutch Famine of 1944-45 as a human laboratory: changes in the early life environment and adult health. In: Lumey L, Vaiserman A, editors. Early life nutrition and adult health and development: lessons from changing dietary patterns, famines, and experimental studies. London: Nova; 2013. pp. 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forsdahl A. Are poor living conditions in childhood and adolescence an important risk factor for arteriosclerotic heart disease? Br J Prev Soc Med. 1977;31:91–95. doi: 10.1136/jech.31.2.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barker DJ. The intrauterine origins of cardiovascular and obstructive lung disease in adult life. The Marc Daniels Lecture 1990. J R Coll Physicians Lond. 1991;25:129–133. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hales CN, Barker DJ, Clark PM, Cox LJ, Fall C, Osmond C, et al. Fetal and infant growth and impaired glucose tolerance at age 64. BMJ. 1991;303:1019–1022. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6809.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ong KE, Loos RJ. Rapid infancy weight gain and subsequent obesity: systematic reviews and hopeful suggestions. Acta Pediatr. 2006;95:904–908. doi: 10.1080/08035250600719754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hofman PL, Regan F, Jackson WE, Jefferies C, Knight DB, Robinson EM, et al. Premature birth and later insulin resistance. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2179–2186. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ong KK, Dunger DB. Birth weight, infant growth and insulin resistance. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151(Suppl 3):U131–U139. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.151u131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boersma B, Wit JM. Catch-up growth. Endocr Rev. 1997;18:646–661. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.5.0313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prader A, Tanner JM, von Harnack G. Catch-up growth following illness or starvation. An example of developmental canalization in man. J Pediatr. 1963;62:646–659. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(63)80035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Djiane J, Attig L. Role of leptin during perinatal metabolic programming and obesity. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2008;59(Suppl 1):55–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parlee SD, MacDougald OA. Maternal nutrition and risk of obesity in offspring: the Trojan horse of developmental plasticity. Biochim Bophysica Acta. 2014;1842:495–506. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bertotto ML, Valmórbida J, Broilo MC, Campagnolo PD, Vitolo MR. Association between weight gain in the first year of life with excess weight and abdominal adiposity at preschol age. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2012;30:507–512. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yeung MY. Postnatal growth, neurodevelopment and altered adiposity after preterm birth-from a clinical nutrition perspective. Acta Pediatr. 2006;95:909–917. doi: 10.1080/08035250600724507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Uthaya S, Thomas EL, Hamilton G, Doré CJ, Bell J, Modi N. Altered adiposity after extremely preterm birth. Pediatr Res. 2005;57:211–215. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000148284.58934.1C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ibáñez L, Ong K, Dunger DB, Zegher F. Early development of adiposity and insulin resistance after catch-up weight gain in small-for-gestational-age. JCEM. 2006;91:2153–2158. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beltrand J, Nicolescu R, Kaguelidou F, Verkauskiene R, Sibony O, Chevenne D, et al. Catch-up growth following fetal growth restriction promotes rapid restoration of fat mass but without metabolic consequences at one year of age. PLoS One. 2009;4:E5343–E5350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas EL, Al Saud NB, Durighel G, Frost G, Bell JD. The effect of preterm birth on adiposity and metabolic pathways and the implications for later life. Clin Lipidol. 2012;7:275–288. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huxley R, Neil A, Collins R. Unravelling the fetal origins hypothesis: is there really an inverse association between birthweight and subsequent blood pressure? Lancet. 2002;360:659–665. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09834-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Spencer HG, Bateson P. Environmental influences during development and their later consequences for health and disease: implications for the interpretation of empirical studies. Proc Biol Sci. 2005;272:671–677. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.3001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gluckman PD, Hanson MA. The developmental origins of the metabolic syndrome. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2004;15:183–187. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gluckman PD, Hanson MA, Spencer HG. Predictive adaptive responses and human evolution. Trends Ecol Evol. 2005;20:527–533. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilcox A. On the importance-and the unimportance-of birthweight. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:1233–1241. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.6.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gilbert-Barness E. Teratogenic causes of malformations. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2010;40:99–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hornberger LK. Maternal diabetes and the fetal heart. Heart. 2006;92:1019–1021. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.083840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vickers M, Gluckman PD, Coveny A, Hofman PL, Cutfield W, Gertler A, et al. Neonatal leptin treatment reverses developmental programming. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4211–4216. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fu Q, Yu X, Callaway CW, Lane RH, McKnight RA. Epigenetics: intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) modifies the histone code along the rat hepatic IGF-1 gene. FASEB J. 2009;23:2438–2449. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-124768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bogdarina I, Welham S, King PJ, Burns SP, Clark AJ. Epigenetic modification of the renin-angiotensin system in the fetal programming of hypertension. Circ Res. 2007;100:520–526. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000258855.60637.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leibowitz SF, Chang GQ, Dourmashkin JT, Yun R, Julien C, Pamy PP. Leptin secretion after a high-fat meal in normal-weight rats: strong predictor of long-term body fat accrual on a high-fat diet. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;290:E258–E267. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00609.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pico C, Palou A. Perinatal programming of obesity: an introduction to the topic. Front Physiol. 2013;4:255. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hanson M, Godfrey KM, Lillycrop KA, Burdge GC, Gluckman PD. Developmental plasticity and developmental origins of non-communicable disease: theoretical considerations and epigenetic mechanisms. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2011;106:272–280. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kehinde OA, Njokanma OF, Olanrewaju D. Parental socioeconomic status and birth weight distribution of Nigerian term newborn babies. Niger J Paed. 2013;40:299–302. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perez-Pereira M, Fernandez P, Gómez-taibo M, Gonzalez L, Trisac JL, Casares J, et al. Neurobehavioral development of preterm and full term children: biomedical and environmental influences. Early Hum Dev. 2013;89:401–409. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Addo OY, Stein AD, Fall CH, Gigante DP, Guntupalli AM, Horta BL, et al. Maternal height and child growth patterns. J Pediatr. 2013;163:549–554. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rotteveel J, van Weissenbruch MM, Twisk JW, Delemarre-Van de Waal HA. Infant and childhood growth patterns, insulin sensitivity, and blood pressure in prematurely born young adults. Pediatrics. 2008;122:313–321. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]