ABSTRACT

In the present study, the crystal structure of recombinant diphosphomevalonate decarboxylase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus was solved as the first example of an archaeal and thermophile-derived diphosphomevalonate decarboxylase. The enzyme forms a homodimer, as expected for most eukaryotic and bacterial orthologs. Interestingly, the subunits of the homodimer are connected via an intersubunit disulfide bond, which presumably formed during the purification process of the recombinant enzyme expressed in Escherichia coli. When mutagenesis replaced the disulfide-forming cysteine residue with serine, however, the thermostability of the enzyme was significantly lowered. In the presence of β-mercaptoethanol at a concentration where the disulfide bond was completely reduced, the wild-type enzyme was less stable to heat. Moreover, Western blot analysis combined with nonreducing SDS-PAGE of the whole cells of S. solfataricus proved that the disulfide bond was predominantly formed in the cells. These results suggest that the disulfide bond is required for the cytosolic enzyme to acquire further thermostability and to exert activity at the growth temperature of S. solfataricus.

IMPORTANCE This study is the first report to describe the crystal structures of archaeal diphosphomevalonate decarboxylase, an enzyme involved in the classical mevalonate pathway. A stability-conferring intersubunit disulfide bond is a remarkable feature that is not found in eukaryotic and bacterial orthologs. The evidence that the disulfide bond also is formed in S. solfataricus cells suggests its physiological importance.

INTRODUCTION

Protein disulfide bonds are often found in proteins that are secreted outside the cells, including those transported into the oxidative cellular compartments of eukaryotes, such as endoplasmic reticulum, or into the periplasmic space of Gram-negative bacteria, and these bonds are also found in redox-active proteins, such as thioredoxin and in redox sensors in oxidized forms (1). Sometimes, these bonds can confer stability to a protein by increasing the number of covalent bonds, which would strengthen the three-dimensional fold of the protein. Mutagenesis of cysteine residues that form disulfide bonds in a protein is occasionally reported to generate unstable mutants. In contrast, the introduction of disulfide bonds is regarded as a technique of protein engineering to create a more stable protein (2). Historically, protein disulfide bonds were believed to sparsely form in the highly reducing cytosol of prokaryotic microorganisms. This belief is generally true, but recent studies have refuted it by revealing the exceptional fact that intracellular proteins from thermophilic microorganisms, mainly hyperthermophilic archaea such as Sulfolobus solfataricus and Pyrobaculum aerophilum, far more commonly possess disulfide bonds. T. O. Yeates’s group performed earlier comprehensive studies on this phenomenon. Those studies showed structural and biochemical evidence of the thermostabilizing effects of disulfide bonds on several proteins (3, 4) and produced genomic and proteomic data that indicated prevailing disulfide bond formation in the cells of such thermophiles. For example, by using two-dimensional diagonal SDS-PAGE, they identified several intermolecular disulfide-bonded proteins from P. aerophilum (5). The group also found a strong bias toward an even number of cysteines in each protein from P. aerophilum and some other thermophilic archaea, which suggests the common occurrence of disulfide bond formation in the microorganisms (6, 7). This frequent disulfide formation in such thermophilic archaea was also supported by the fact that a high percentage of the cysteine residues in the crystal structures of the proteins from the microorganisms tend to form disulfide bonds (8).

Pedone et al. have proposed that thermophilic protein disulfide oxidoreductase (PDO), which is a member of the thioredoxin family, plays a main role in the cytoplasmic disulfide formation in thermophilic microorganisms, such as S. solfataricus (9, 10). The microorganisms possessing thermophilic PDO seem to agree with those listed by Yeates’s group as the producers of abundant disulfide-bonded proteins in the cytosol (6, 7). Thus far, a number of studies, most of which are based on crystallographic data, have also suggested the formation of disulfide bonds in nonredox cytosolic proteins from thermophilic microorganisms (11–20), although not all of the microorganisms possess PDO. To be exact, none of these studies directly proved that the disulfide bonds were formed in vivo since the authors used recombinant proteins expressed in Escherichia coli for analysis, which means that the disulfide bonds they observed were formed during purification and/or crystallization processes. Even if the proteins were prepared from the original organisms, disulfide bonds could be formed through aerobic manipulation of the proteins, and in such cases, no one can claim that the redox states of the proteins are the same as those are in vivo. By using thiol-labeling techniques, a few reports have demonstrated that there are a large number of proteins possessing disulfide bonds in the cells of P. aerophilum and S. solfataricus (6, 21); however, as far as we could ascertain, there is no report that has clearly shown the redox state of a certain protein—i.e., what percentage of the protein is in the oxidized form—in the cells of thermophiles, while Heinemann et al. recently reported that the cytosol of S. solfataricus lacks reduced small molecule thiols like glutathione and that glutathione is mainly in the oxidized, disulfide-bonded form in the cells (21).

In the present study, we solved the crystal structures of diphosphomevalonate decarboxylase (DMD) from S. solfataricus, which had been discovered recently by us as the first archaeal DMD (22). DMD is an enzyme of the classical mevalonate (MVA) pathway and catalyzes the conversion of mevalonate diphosphate (MVAPP) into isopentenyl diphosphate (23, 24), accompanying the hydrolysis of ATP to ADP and inorganic phosphate. Isopentenyl diphosphate is essential for archaea because it is a biosynthetic precursor of isoprenoid compounds, including archaeon-specific membrane lipids. However, DMD is very rare in archaea, because almost all archaea utilize the modified MVA pathways that do not involve DMD (25, 26). S. solfataricus is the only example of archaea that has been proven to date to possess the classical MVA pathway (22). The crystal structures of DMD have been solved with the enzymes from several eukaryotes (Saccharomyces cerevisiae [27], Trypanosoma brucei [28], Homo sapiens [29], and Mus musculus), and bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus [28], Staphylococcus epidermidis [30, 31], Streptococcus pyogenes, and Legionella pneumophila). Most of the known DMD structures have been reported as homodimers, as elucidated biochemically for some eukaryotic enzymes (32–34), while DMD from Trypanosoma brucei was shown to be monomeric (28). The homodimer formation of DMD is supposedly important for its stability, because a temperature-sensitive L79P mutant of S. cerevisiae DMD, which usually forms a homodimer, was shown by two-hybrid assay to be monomeric (35, 36). The structure of S. solfataricus DMD, which also forms a homodimer, basically resembles those of eukaryotic and bacterial DMDs. Interestingly, however, its monomeric subunits are connected via a disulfide bond at the dimer interface. To understand the physiological importance of the disulfide bond, we examined the effect of the disulfide formation on the thermotolerance of recombinant S. solfataricus DMD via site-directed mutagenesis or reductive scission of the disulfide bond and surveyed the efficiency of the in vivo formation of the disulfide bond via nonreducing SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis of whole cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Recombinant expression and purification of S. solfataricus DMD.

Enzyme expression using E. coli Rosetta(DE3) transformed with the pET-16b vector into which the sso2989 gene had been inserted (pET-SsoDMD) and partial purification with affinity chromatography using a 1-ml Histrap FF crude column (GE Healthcare) were performed as described in our previous study (22). The purified enzyme fraction containing DMD fused with an N-terminal polyhistidine tag was diluted with a 10-fold volume of a factor Xa cleavage buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.1 M NaCl, and 5 mM CaCl2, which was then reacted with 400 U of factor Xa (Merck Millipore, Germany) at 22°C for 16 h. The solution was then loaded onto a Histrap FF crude column to remove the cleaved polyhistidine tag. The flowthrough fraction was then recovered, transferred to a cellulose membrane tube (Sanko Jyunyaku Co., Japan), and dialyzed overnight against buffer A, which contained 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.7), 1 mM EDTA, and 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol. The dialyzed solution was loaded onto a Mono Q 5/50 column (GE Healthcare), and the column was washed with 10 ml of buffer A. The enzyme was eluted from the column with 20 ml of buffer A containing NaCl with a linear gradient that ranged from 0 to 0.3 M. The flow rate of the buffer was 0.5 ml/min. The eluate fractions containing the enzyme were gathered and condensed to 1 ml using an Amicon Ultra 10,000-molecular-weight cutoff (MWCO) centrifugal filter (Merck Millipore). The enzyme solution was loaded onto a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 prep-grade column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with buffer A, which additionally contained 0.15 M NaCl. The enzyme was eluted from the column with the same buffer, and the eluate fractions containing purified S. solfataricus DMD were gathered and condensed using Amicon Ultra 10,000-MWCO filters until the enzyme concentration reached 20 mg/ml. The presence and the purity of the enzyme were analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE. The enzyme concentration was measured via the Bradford method (37).

Crystallization, X-ray data collection, structure solution, and refinement.

The purified recombinant S. solfataricus DMD was crystallized at 20°C using the hanging-drop vapor diffusion method. Reservoir solutions for crystallization were screened using Crystal Screen and Crystal Screen 2 reagent kits (Hampton Research), and these were then optimized for the growth of crystals. Two different reservoir solutions were used to obtain crystals for data collection. One was 100 μl of 0.1 M HEPES sodium (pH 7.5) containing 0.8 M sodium phosphate monobasic, 0.8 M potassium phosphate monobasic, and 15% glycerol. The volume of the reservoir solution was 100 μl, and a drop was prepared by mixing 2 μl of the purified enzyme solution and 2 μl of the reservoir solution. The crystals formed with the solution (crystal type, DMD-P) were directly used for data collection. The other reservoir solution was 0.1 M sodium acetate trihydrate (pH 4.6) containing 1.5 M ammonium sulfate. After the crystals were grown, the reservoir solution was exchanged with 100 μl of 0.1 M sodium acetate (pH 4.6), which contained 3.0 M ammonium sulfate for cryoprotection. After 2 weeks of equilibration, the crystals (crystal type; DMD-AS) were used for X-ray data collection. Diffraction data from crystal types AS and P were collected via a beamline AR-NW12A at the Photon Factory (Tsukuba, Japan). Data indexing, integration, and scaling were carried out using the CCP4 programs (38) Mosflm (39) and SCALA (40). The data collection statistics are summarized in Table 1. The DMD-P and DMD-AS data sets belonged to space groups H32 and P21, respectively. The data sets were used for phase calculation via a molecular replacement method, in which the BALBES program (41) automatically performed the calculation with a series of search models that have a sequence homology with SsoDMD. Finally, using 2HKE and 2HK2 as search models for the calculation, we obtained the correct phases, respectively. The structures were built using the ARP/wARP (42) and COOT (43) programs and were refined using Refmac (44), with 5% of the data set aside as a free set. Models of phosphate, sodium, glycerol, and sulfate were placed based on different electron density maps. The superposition of the structures was performed using the program SUPERPOSE (45). The final model, comprised of residues ranging from 2 to 325, agreed with the crystallographic data with values for Rwork/Rfree of 21.1%/23.7% (DMD-P) and 25.4%/27.7% (DMD-AS), respectively (Table 1). The secondary structure was assigned by DSSP (46). All figures were produced using PyMOL software (http://www.pymol.org).

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Parameter | Result(s) for crystal typea: |

|

|---|---|---|

| DMD-P | DMD-AS | |

| Data collection and processing statistics | ||

| Beamline | AR-NW12A | AR-NW12A |

| Space group | H32 | P21 |

| Unit cell dimensions | ||

| a (Å) | 152.1 | 94.9 |

| b (Å) | 152.1 | 154.4 |

| c (Å) | 108.6 | 110.0 |

| β (°) | 114.4 | |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Resolution (Å) | 45.3–2.20 (2.32–2.20) | 50.0–2.70 (2.85–2.70) |

| Unique reflections (no.) | 23,569 | 78,276 |

| I/σ〈I〉 | 22.6 (7.9) | 16.4 (5.1) |

| Redundancy | 15.4 (15.7) | 3.7 (3.7) |

| Completeness (%) | 96.4 (96.8) | 96.6 (95.4) |

| Rmerge (%)b | 7.5 (26.3) | 5.5 (22.4) |

| Refinement statistics | ||

| Resolution | 45.3–2.20 | 47.63–2.70 |

| Protein molecules/asymmetric unit (no.) | 1 | 6 |

| Protein atoms (no.) | 2,597 | 15,582 |

| Ligand molecules (no.) | ||

| Phosphate | 2 | 0 |

| Sodium | 1 | 0 |

| Glycerol | 1 | 0 |

| Sulfate | 0 | 6 |

| Ligand atoms (no.) | 17 | 30 |

| Water molecules (no.) | 140 | 81 |

| Rwork/Rfree (%) | 21.1/23.7 | 25.4/27.7 |

| Root mean square deviation | ||

| Bond length (Å) | 0.009 | 0.010 |

| Bond angle (°) | 1.374 | 1.496 |

| Ramachandran statistics (%) | ||

| Residues in favored region | 96.6 | 96.5 |

| Residues in allowed region | 3.1 | 3.1 |

| Residues in outlier region | 0.3 | 0.4 |

Numbers in parentheses are for the highest-resolution shell.

Rmerge = 100Σ|I − 〈I〉|/Σ I, where I is the observed intensity and 〈I〉 is the average intensity of multiple observations of symmetry-related reflections.

Gel filtration column chromatography.

Polyhistidine-tagged recombinant S. solfataricus DMD, purified using an affinity column as described above, was dialyzed with three types of buffer solution: solution 1, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.7) containing 1 mM EDTA and 0.15 M NaCl; solution 2, 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.7) containing 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.15 M NaCl; and solution 3, 100 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.4) containing 1 mM EDTA and 0.15 M NaCl. Each of the dialyzed enzyme solutions was concentrated with a VivaSpin 20 10,000-MWCO centrifugal filter (GE Healthcare) and was loaded onto a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 prep-grade column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with the same buffer solution used for dialysis. Elution of the enzyme was also performed with the same buffer solution. To construct a molecular standard curve, a gel filtration standard (Bio-Rad), which contained several proteins and a small molecule, was applied afterward to the same column.

DLS analysis.

Polyhistidine-tagged recombinant S. solfataricus DMD in solution 1 or 3 for the gel filtration analysis was used for dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis on a Zetasizer nano (Malvern Instruments). After filtration with a 0.45-μm-pore-size membrane, 200 μl of each enzyme solution, diluted to a concentration of 0.5, 1.0 or 1.5 mg/ml, was analyzed to determine the average hydrodynamic radius size (RH) of an enzyme particle in the solution. The calculation of the radius of gyration (Rg) from the crystal structure of the enzyme was conducted using a CRYSOL program (47).

Site-directed mutagenesis.

A single-amino-acid replacement (C210S) mutation on S. solfataricus DMD was introduced into pET-SsoDMD using a QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and oligonucleotide primers 5′-CAGAACTAATGGAAAGTAGGCTTAAATAC-3′ and 5′-GTATTTAAGCCTACTTTCCATTAGTTCTG-3′. The recombinant expression and purification of the mutant were performed by the same methods used for the wild-type enzyme.

Secondary structure analysis by far-UV CD spectroscopy.

The buffer solution of polyhistidine-tagged recombinant S. solfataricus DMD was exchanged into 20 mM sodium phosphate at pH 7.4 containing 0.5 M NaCl, using an Amicon Ultra 10,000-MWCO filter. The 0.2-mg/ml enzyme solution was used for the far-UV circular dichroism (CD) analysis and for the thermostability analysis described later. The heat-induced change in the secondary structures (α-helixes) of both the wild-type and the C210S mutant enzymes was measured using a J-720WI spectropolarimeter (Jasco, Japan) equipped with a PTC-348WI thermoelectric temperature controller. Ellipticity at 222 nm was monitored during the rise of the cell temperature from 60 to 110°C at a rate of 1°C/min.

Reductive heat treatment and enzyme assay.

Nine hundred microliters of a premixed solution for the enzyme reaction, containing 73 μmol of potassium phosphate at pH 7.0, 5 μmol of MgCl2, 0.16 μmol of NADH, 4 μmol of ATP, 5 μmol of phosphoenol pyruvate, and 600 μg of recombinant S. solfataricus DMD, was prepared and treated at different temperatures (60, 70, 80, or 90°C) for 1 h in the presence or absence of 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol. After the heat treatment, the precipitated enzyme was removed by centrifugation. After addition of 10 U of pyruvate kinase from rabbit muscle (Sigma-Aldrich) and 10 U of lactate dehydrogenase from a porcine heart (Oriental Yeast, Japan), 225 μl of the premixed solution was dispensed into each of the wells of a 96-well microtiter plate. To each well, 25 μl of 5 mM (R,S)-MVAPP (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to begin the enzyme reaction. The assay was performed at 28°C, and the change in the A340 was measured using a Multiskan FC microplate spectrophotometer (Thermo) at intervals of 2 min. The specific activity of S. solfataricus DMD was calculated from the initial rate of decrease in the absorption (−ΔA340/min), using the absorption coefficient for NADH, ε = 6,220 M−1 cm−1.

Nonreducing SDS-PAGE analysis.

The factor Xa-cleaved recombinant S. solfataricus DMD solution (used as the untreated enzyme) was reduced or oxidized by mixing with 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol or diamide, respectively, at room temperature. Each of the untreated, reduced, and oxidized enzymes was then mixed with the same volume of 2× nonreducing SDS-PAGE sample buffer, containing 0.125 M Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 4% (wt/vol) SDS, 20% (wt/vol) glycerol, and 0.01% (wt/vol) bromophenol blue, which was then boiled for 5 min, and 10 μl of each sample solution was analyzed via 8% SDS-PAGE. The gel was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue.

Western blotting.

S. solfataricus P2, which was provided by the RIKEN BioResource Center through the Natural Bio-Resource Project of the MEXT, Japan, was cultured in ATCC 1304 S. solfataricus medium at 80°C and harvested during the late log phase. The intact cells of S. solfataricus were suspended in and diluted with an isotonic medium containing 10 mM ammonium sulfate, 2 mM monopotassium phosphate, 1 mM magnesium sulfate, 2% glycerol, and an appropriate amount of sulfuric acid for a pH adjustment to 3.0. The diluted solution containing ∼60 mg wet cells/ml was analyzed by nonreducing SDS-PAGE as described above along with 8 μg/ml of the untreated and reduced recombinant S. solfataricus DMD. The processes of mixing with the SDS-PAGE sample buffer and boiling were performed as quickly as possible to avoid disulfide formation before the denaturing of DMD. Reduction of the lysed cell sample was performed at the same time by replacing the nonreducing SDS-PAGE sample buffer with the usual SDS-PAGE sample buffer to add β-mercaptoethanol at a final concentration of 280 mM. After electrophoresis, proteins were separated in the gel and transferred to an Amersham Hybond-P polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (GE Healthcare) using a Trans-Blot SD semidry transfer cell (Bio-Rad). S. solfataricus DMD on the membrane was detected by Western blot staining using a polyclonal rabbit antiserum against the enzyme (Operon Biotechnology, Japan) and an anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP). Because Precision Plus Protein WesternC standards (Bio-Rad) were used as molecular weight markers for SDS-PAGE, StrepTactin-HRP conjugate (Bio-Rad) was added to the secondary antibody reaction for the detection of the markers. Chemiluminescence detection was performed using a Clarity Western ECL (enhanced chemiluminescence) substrate (Bio-Rad) with a CoolSaver AE-6955 chemiluminescence detector (ATTO Co., Japan), according to the manufacturer's protocol. For the analysis of recombinant DMD expressed in E. coli cells, cell suspension was performed with 125 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8) containing 2% glycerol, and a solution of ∼160 μg wet cells/ml was used for nonreducing SDS-PAGE.

Protein structure accession numbers.

The crystallography data, atomic coordinates, and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB; www.pdb.org) under PDB ID no. 4Z7C for DMD-P and 4Z7Y for DMD-AS.

RESULTS

Crystal structures of S. solfataricus DMD.

Soon after our discovery of the first archaeal DMD from S. solfataricus (22), we began an X-ray crystallographic study to reveal the structural differences between the enzyme derived from the hyperthermophilic archaeon and known DMDs from mesophilic bacteria and eukaryotes. Two different conditions for crystallization gave crystals with different space groups, having qualities that were sufficient for X-ray diffraction analysis (crystal DMD-P and DMD-AS) (Table 1). The structures from the two lines of crystals were independently determined using the molecular replacement method, and these have been refined to resolutions of 2.2 Å (DMD-P) and 2.7 Å (DMD-AS). The electron density map of DMD-P and DMD-AS included the main chains and a large part of the side chains of the solved structures, while that for the regions corresponding to the side chains of residues 51 to 71, 81 to 91, and 187 to 191, which were located on the surface of the structures, were unidentified. The validation reports (48) of the structures gave high ratios for the side-chain outliers (DMD-P, 6.2%; DMD-AS, 8.2%) and RSRZ outliers (DMD-P, 7.7%; DMD-AS, 12.7%), which could have been caused by disorders in these side chains. Most of the residues in the structures lay within the preferred and allowed regions of the Ramachandran plot, whereas Asp24 (DMD-AS) and Asp281 (DMD-P and DMD-AS) fell into the disallowed region of the plot.

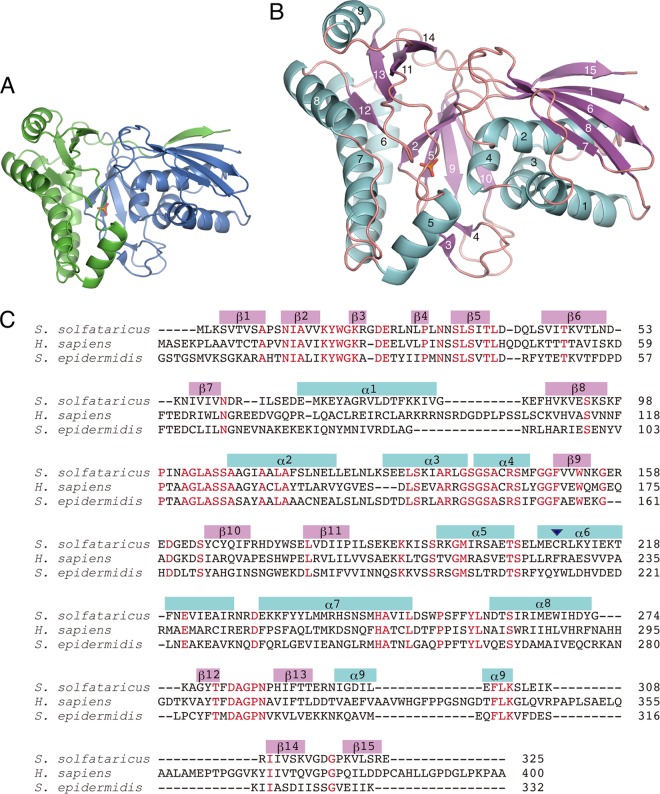

The solved two structures are basically similar, albeit with different numbers of DMD and bound inorganic molecules in each asymmetric unit. The structure of DMD-P is composed of one DMD molecule, two phosphate molecules, one sodium molecule, and one glycerol molecule in the asymmetric unit, with one inorganic phosphate molecule lying on a crystallographic 3-fold axis (Fig. 1A). The other phosphate and glycerol molecules are bound at a large cleft in the structure. A DMD molecule is composed of two domains: N (residues 2 to 173) and C (residues 174 to 325) terminals. Each of the domains consists of β-strands and α-helices that are numbered as shown in Fig. 1B and C. The N-terminal domain comprises four α-helices (α1 to α4) and 3 units of a β-sheet with the β-strands arranged in the order β1-β6-β8-β7, β2-β5-β9-β10 (antiparallel), and β3-β4 (antiparallel) surrounding the helices. The C-terminal domain has five α-helices (α5 to α9), a β-sheet (β12-β13-β11-β14), and an outstanding β-strand (β15) only that constitutes a β-sheet (β15-β1-β6-β8-β7) in the N-terminal domain. These structural features of S. solfataricus DMD have also been found in the structures of DMDs reported thus far from eukaryotes and bacteria. However, the whole structure of the archaeal enzyme apparently resembles those of bacterial DMDs rather than eukaryotic DMDs, because it lacks the additional loop-helix-loop structures that are typically composed of ∼30 amino acids and are found only in eukaryotic DMDs (the region corresponding with that around α10 in Fig. 1C).

FIG 1.

Crystal structure of recombinant DMD from S. solfataricus. (A) Monomer subunit structure of DMD-P in ribbon representation. N- and C-terminal domains are colored blue and green, respectively. A phosphate molecule bound in a cleft in DMD-P is shown as a stick model. (B) Ribbon diagram of S. solfataricus DMD-P subunit. α-Helices and β-strands, labeled in the order of appearance, are colored light blue and pink, respectively. The phosphate molecule bound to DMD-P is shown as a stick model. (C) Amino acid sequences of DMD from S. solfataricus, H. sapiens, and S. epidermidis are aligned. Conserved residues are colored red. α-Helices and β-strands in S. solfataricus are indicated as boxes in blue and pink, respectively. An arrowhead in the region of α6 represents the Cys210 residue of S. solfataricus DMD, which is involved in intersubunit disulfide bond formation.

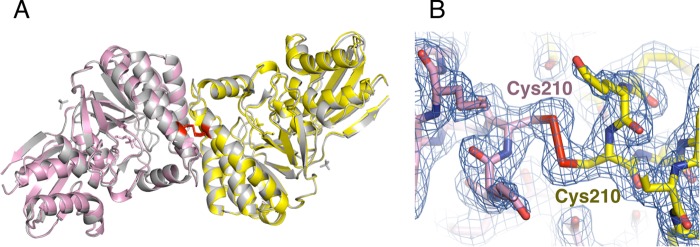

Intriguingly, in the DMD-P structure, a covalent disulfide bridge was observed between the neighboring DMD molecules, forming a 2-fold crystallographic symmetry (Fig. 2A and B). Covalent disulfide bridges have also been identified in the DMD-AS structure with the same arrangement, while the asymmetric unit of DMD-AS is composed of three covalent-bridged DMD dimers and six sulfate molecules. The root mean square deviations of protomers (0.260 Å) and covalent-bridged dimers (0.476 Å) between DMD-P and DMD-AS show that the structures of these protomers are essentially the same (Fig. 2A) and that a slight deviation between the covalent-bridged dimers is caused by a difference in crystal packing. The subunits of dimers are tightly associated, where a buried area of 1343 Å2 and 8 hydrogen bonds are included in addition to a covalent disulfide bridge. The relative orientation of the protomer and the interface for the dimerization of S. solfataricus DMD are similar to those of eukaryotic and bacterial DMDs whose biological units are also dimers. Therefore, the biological unit of S. solfataricus DMD is supposed to be a dimer, where the intermolecular interaction for the dimerization would be enforced largely by covalent bonding. A calculation of the probable assemblies of S. solfataricus DMD-AS using the PISA program (49), which is based on chemical thermodynamics, indicated only a covalent-bridged dimer as the biological unit, while that of S. solfataricus DMD-P suggested two possibilities: a covalent-bridged dimer and a hexamer. The hexamer was composed of three covalently bridged dimers related to the crystallographic 3-fold axis and inorganic phosphate molecules located on the axis. The proposed hexameric structure in the DMD-P closely agreed with the orientation of six molecules in an asymmetric unit of the DMD-AS. The intermolecular interaction in the hexameric structure included a buried area of 2,301 Å2 and 15 hydrogen bonds per protomer, which was 1.7-fold larger than that needed to form a dimer. Given that a product from the DMD reaction (i.e., inorganic phosphate) is involved in the formation of the hexamer structure, the multimeric structure of the enzyme could possibly change in the presence or absence of inorganic phosphate and might affect the enzyme activity. Gel filtration column chromatography of the enzyme using 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.7) containing 1 mM EDTA and 0.15 M NaCl (solution 1) gave a calculated molecular mass of 40 kDa, which approximates that expected for a monomer (37 kDa) and obviously is smaller than that for a dimer. Change in the buffer to 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.7) containing 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.15 M NaCl (solution 2), however, also gave a similar calculated mass of 42 kDa, suggesting that the enzyme took the same quaternary structure in both the oxidative and reductive buffers and that an interaction between the enzyme and the column caused the late elution time. The use of 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 1 mM EDTA and 0.15 M NaCl (solution 3) for gel filtration column chromatography resulted in a slightly faster elution of the enzyme, which gave a calculated molecular mass of 53 kDa. The increase in the calculated mass was, however, not so large that the formation of a hexamer could be suggested. Thus, we performed DLS analysis of the recombinant enzyme in both solutions 1 and 3 used for gel filtration column chromatography. At the concentrations between 0.5 and 1.5 mg/ml, the average hydrodynamic radius size (RH) of the enzyme ranged from 5.00 to 5.25 nm for solution 1 and from 4.95 to 5.73 nm for solution 3, which showed that the presence of the inorganic phosphate did not affect the quaternary structure of S. solfataricus DMD. The radii of gyration (Rg) were calculated to be 2.95 and 3.96 nm for a dimer and a hexamer, respectively, from the crystal structure of the protein (47). RH should be equivalent to 5/3 Rg if the electron density of the protein is equable. This means that the RH of the dimer and the hexamer of S. solfataricus DMD, as estimated from its crystal structure, would be 4.92 nm and 6.60 nm, respectively. The results from the DLS measurement suggest that the quaternary structure of the enzyme is a dimer.

FIG 2.

Quaternary structure of recombinant S. solfataricus DMD. (A) Dimer structures of S. solfataricus DMD-P and DMD-AS in ribbon representation. The subunits of DMD-P are shown in yellow and pink, and those of DMD-AS are shown in gray. Phosphate and glycerol molecules bound to DMD-P and sulfate molecules to DMD-AS are shown as stick models. Disulfide bonds between protomers are shown as red stick models. (B) Intersubunit disulfide bond in the DMD-P structure is shown as stick models with the 2Fo − Fc electron density map at the 1.5σ level (blue). Stick models of the protomers are shown in the same colors used for panel A.

Effect of disulfide bond formation on thermostability.

The disulfide bond between the Cys210 residues of the recombinant S. solfataricus DMD is thought to emerge during enzyme purification performed under aerobic conditions, because it is unlikely to be an original part of the enzyme expressed in the reducing cytosol of E. coli, where disulfide bonds are rarely formed. It is noteworthy that S. solfataricus DMD has three cysteine residues and that no electric density was observed between the remaining Cys143 and Cys166 residues, while they were within a proximal distance (3.32 Å between their sulfur atoms in DMD-P) suitable for the formation of a disulfide bond in each subunit (data not shown). Cys143 and Cys166 exist inside the hydrophobic core of a subunit, while the intersubunit disulfide bond between Cys210 and Cys210′ exists on the surface of the dimer structure. The formation of intersubunit disulfide bonds has never been observed in the structures of eukaryotic and bacterial DMDs, and the cysteine residue corresponding to Cys210 of S. solfataricus DMD is not conserved among them. Meanwhile, the cysteine residue is highly conserved among the DMD orthologs from the order Sulfolobales (data not shown). Because the known members of Sulfolobales are all thermophiles, the disulfide bond is anticipated to confer a tolerance to high temperatures to their enzymes.

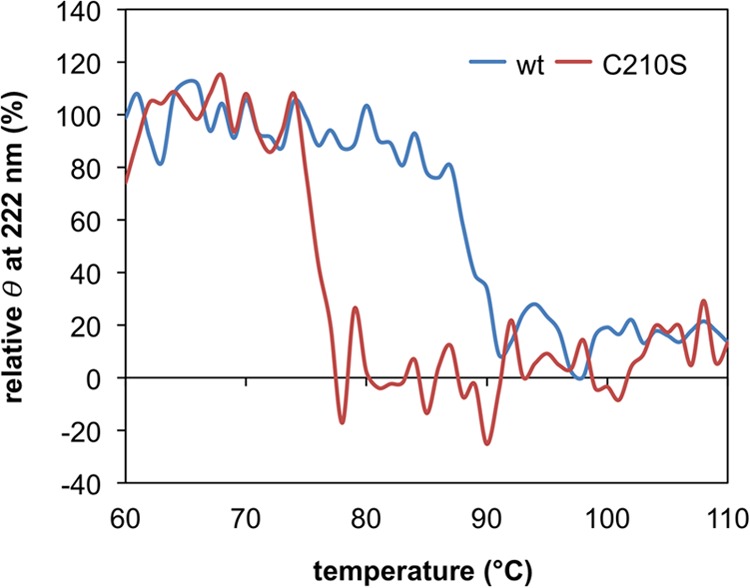

To show the importance of the intersubunit disulfide bond on the thermostability of S. solfataricus DMD, we constructed a mutant enzyme in which Cys210 was replaced with serine. The mutant C210S and the wild-type DMD were purified to perform CD spectrometry analysis, which allowed us to estimate the ratio of the residual secondary structure of proteins through the rise in temperature. The far-UV CD at 222 nm of the enzyme solution, which represents the presence of α-helices, was monitored during a temperature rise from 60 to 110°C. As shown in Fig. 3, the secondary structure of the C210S mutant decomposed at ∼78°C, while that of the wild-type enzyme was decomposed at ∼90°C. This suggests that the formation of the intersubunit disulfide bond results in an ∼10°C rise in thermostability.

FIG 3.

Heat-induced change in the secondary structure of the recombinant wild-type (wt) S. solfataricus DMD and the C210S mutant through far-UV CD spectroscopy analysis. The vertical axis represents the relative ellipticity (θ) at 222 nm, where the average of ellipticity values from 60 to 69°C for each measurement is set to 100%.

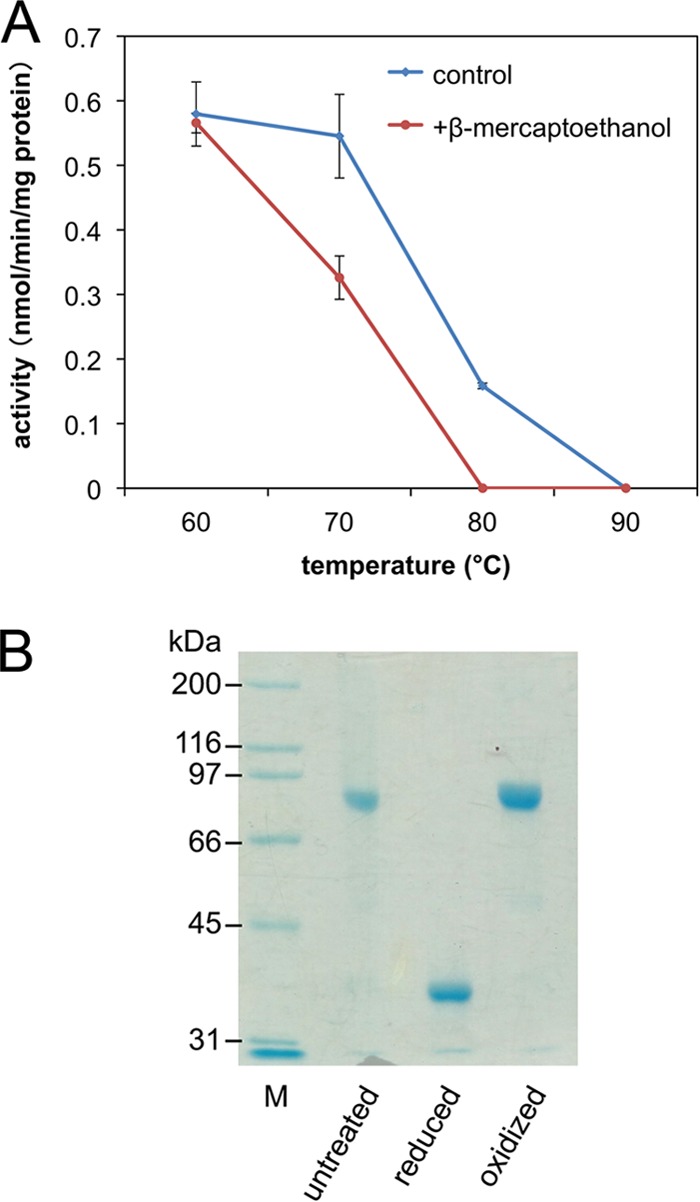

Next, we attempted to confirm this hypothesis by the reductive cleavage of the double bond of a wild-type recombinant S. solfataricus DMD. The enzyme was treated with or without 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol at 60, 70, 80, or 90°C for 1 h. CD spectrometry could not be used to observe the structural decomposition because the addition of the reducing agent had a significant effect on the spectrum. Therefore, following heat treatment, a DMD assay was performed at 28°C by coupling the formation of ADP with the reactions of pyruvate kinase and lactate dehydrogenase. The enzyme activity was detected as the rate of decrease in the absorption of NADH at 340 nm. The activity of recombinant S. solfataricus DMD was decreased by the treatment at 80°C and was fully lost at 90°C (Fig. 4A). In the presence of β-mercaptoethanol, however, the enzyme lost approximately half of its activity at 70°C and was completely inactivated by the treatment at 80°C. A nonreducing SDS-PAGE analysis confirmed the presence of the intersubunit disulfide bond in a major portion of the recombinant enzyme used for the experiment and also the ability of 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol to cleave the disulfide bond (Fig. 4B). This result supports our hypothesis that the formation of the intersubunit disulfide bond makes the enzyme more thermostable.

FIG 4.

Thermostability of recombinant S. solfataricus DMD in the presence and absence of β-mercaptoethanol. (A) DMD activity remaining after 1 h of heat treatment at the indicated temperatures. (B) Nonreducing SDS-PAGE analysis of untreated, reduced, and oxidized S. solfataricus DMD. M, standard molecular mass markers.

Formation of the disulfide bond of DMD in S. solfataricus cells.

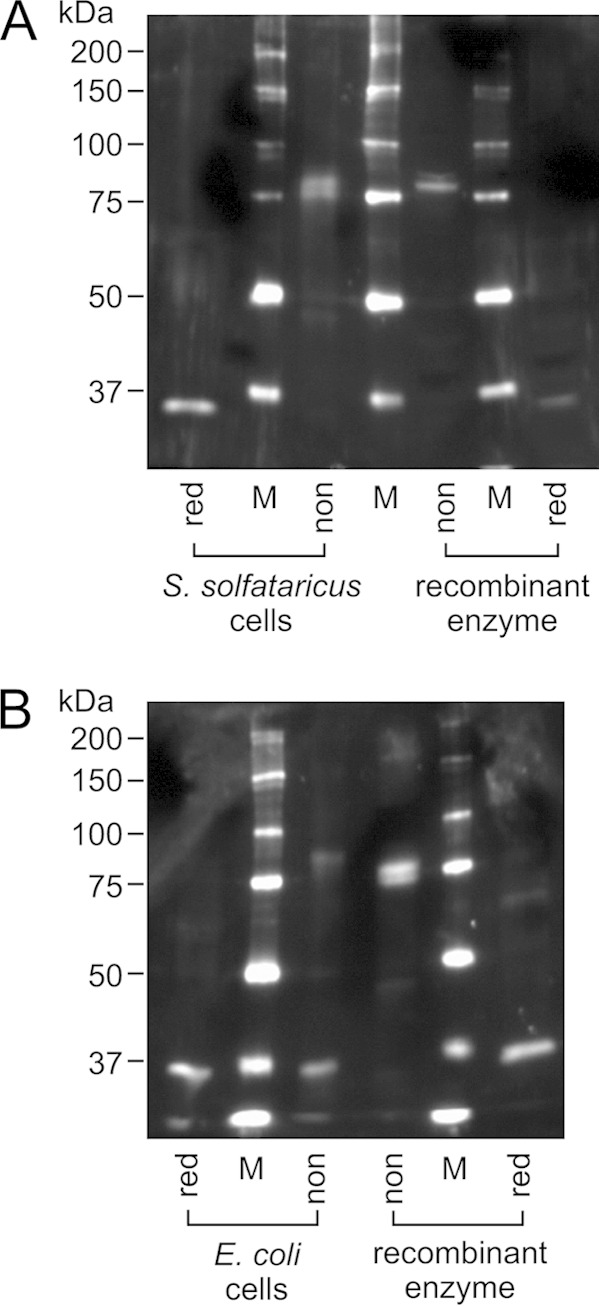

Because ∼80°C is reported as the optimal growth temperature of S. solfataricus (50), and because the inactivation of recombinant DMD occurred at similar temperatures when Cys210 was replaced by serine or when the disulfide bond was reduced, it is tempting to imagine that the formation of the disulfide bond is required for DMD to exhibit activity at the growth temperature of S. solfataricus. However, even though frequent in vivo formation of disulfide bonds in some thermophilic archaea has been proven (6, 21), the efficiency of disulfide formation in each kind of protein is still unclear. Thus, we attempted to examine the formation of the disulfide bond of DMD in the cells of S. solfataricus using nonreducing SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. As suggested by the present study, aerobic manipulation of a protein can cause the a posteriori formation of disulfide bonds. To avoid the oxidation of DMD after leakage from the cells of S. solfataricus, the cells were suspended in an isotonic solution for dilution and were boiled immediately after the addition of the sample buffer that contained a detergent. After the nonreducing SDS-PAGE, endogenous DMD was detected by Western blotting using an anti-DMD antiserum. As with the analysis of purified recombinant DMD shown in Fig. 4B, a band of DMD with a molecular mass corresponding to a connected dimer was detected in the analysis of the nonreduced archaeal cellular sample (Fig. 5A). The treatment of the cellular sample with β-mercaptoethanol gave the reduced form of DMD. This result suggested that the intersubunit disulfide bond between Cys210 residues is also formed in a major portion of DMD in the archaeal cells because the other cysteine residues in S. solfataricus DMD cannot form intersubunit disulfide bonds. In contrast, a similar analysis using E. coli cells that express S. solfataricus DMD showed that the recombinant enzyme is mostly in the reduced form in vivo, as expected (Fig. 5B). These data strongly suggest that the Cys210-Cys210′ intersubunit disulfide bond of DMD is predominantly formed in the cells of S. solfataricus and is likely required to exhibit enzyme activity, particularly when the growth temperature of the archaeon is high. It should be noted that an intrasubunit disulfide bond between Cys143 and Cys166 is possibly formed as well in the archaeal cells and might contribute to a further degree of thermostabilization, although the formation of the Cys143-Cys166 disulfide bond in S. solfataricus cells could not be confirmed because of experimental difficulties.

FIG 5.

Nonreducing SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis of the cells of S. solfataricus (A) and E. coli expressing recombinant S. solfataricus DMD (B). Approximately 300 μg and 0.8 μg wet cells of S. solfataricus and E. coli, respectively, were applied on each lane. The cells were treated with nonreducing (non) or reducing (red) SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Purified recombinant S. solfataricus DMD, untreated (non) and reduced (red), was used as the controls. M, standard molecular mass markers. To avoid the effect of the reducing agent on the redox state of samples on adjacent lanes, the sample lanes were separated by those for markers.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we solved the crystal structures of recombinant S. solfataricus DMD as the first example of those of archaeal and hyperthermophile-derived DMD. An intersubunit disulfide bond between Cys210 residues, which is not conserved in eukaryotic and bacterial orthologs, is one of the most intriguing characteristics of the structures, and its removal, by mutagenesis or reductive scission, decreases thermostability of the enzyme by ∼10°C, suggesting that the disulfide bond helps the enzyme exert activity at the growth temperature of S. solfataricus. We also examined the actual redox state of DMD in the cells of the archaeon, by directly using whole cells for nonreducing SDS-PAGE analysis. Unless the disulfide bond formation occurs almost instantaneously, the result from the analysis can properly reflect the in vivo redox state of the enzyme. Oxidation of DMD was proven not to be a very fast process because the majority of the recombinant enzyme expressed in the cells of E. coli was not oxidized through the nonreducing SDS-PAGE analysis. Based on these results, we concluded that most of the native DMD molecules in S. solfataricus cells also have the Cys210-Cys210′ intersubunit disulfide bond, which enhances the thermostability of the enzyme. This conclusion strongly supports Yeates's theory that disulfide bond formation is a common strategy employed by some thermophilic microorganisms to promote the thermostability of their proteins. To our knowledge, the present study is the first report that demonstrates the high percentage of in vivo disulfide formation in a certain enzyme. At the same time, we also showed the contribution of the disulfide bond to the thermostability of the enzyme. The existence of disulfide bonds in a recombinant protein tends to be treated as proof of disulfide formation in the cells of the original organism. As we demonstrated in the present study, this logic is likely sound when the cytosol of the original organism is known to be oxidizing, like those of S. solfataricus and P. aerophilum. At the same time, however, we should be careful to adopt the same logic for an organism about which information is insufficient. The oxidation of the recombinant protein, which can occur easily through processes of manipulation, does not always guarantee the in vivo formation of the same disulfide bonds. The presence of disulfide bond formation machinery such as PDO in the organism might be helpful in judging whether the disulfide formation also occurs in vivo.

DMD is a rare enzyme in the domain Archaea, although almost all eukaryotes and a large number of bacterial species such as Gram-positive cocci possess it. This comes from the fact that the classical MVA pathway is limited to the order Sulfolobales in Archaea. Instead, the other archaeal species use the modified MVA pathways, which do not go through MVAPP (25, 26, 51, 52). In the modified pathways, isopentenyl diphosphate is formed from isopentenyl phosphate, which is not an intermediate of the classical pathway. However, the biosynthetic routes to convert MVA into isopentenyl phosphate are different among archaeal lineages; for example, MVA 5-kinase and phosphomevalonate decarboxylase are used in a halophilic archaeon Haloferax volcanii (53), and MVA 3-kinase, MVA-3-phosphate 5-kinase, and probably MVA-3,5-bisphosphate decarboxylase are used in a thermophilic archaeon, Thermoplasma acidophilum (54, 55). Among these recently discovered enzymes, phosphomevalonate decarboxylase and MVA 3-kinase are closely related to DMD. Because the crystal structure of T. acidophilum MVA 3-kinase has been reported very recently (56), the comparison of it with the structures of S. solfataricus DMD will give us valuable information about the evolution of these homologous enzymes and of the MVA pathways in the domain Archaea. The substrate complex structures of S. solfataricus DMD will be needed, however, to reveal the molecular mechanisms that lead to the catalysis of reactions different from that catalyzed by MVA 3-kinase.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI grant no. 23580111, 23108531, and 25108712 for H.H.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kadokura H, Katzen F, Beckwith J. 2003. Protein disulfide bond formation in prokaryotes. Annu Rev Biochem 72:111–135. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dombkowski AA, Sultana KZ, Craig DB. 2014. Protein disulfide engineering. FEBS Lett 588:206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toth EA, Worby C, Dixon JE, Goedken ER, Marqusee S, Yeates TO. 2000. The crystal structure of adenylosuccinate lyase from Pyrobaculum aerophilum reveals an intracellular protein with three disulfide bonds. J Mol Biol 301:433–450. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.King NP, Lee TM, Sawaya MR, Cascio D, Yeates TO. 2008. Structures and functional implications of an AMP-binding cystathionine β-synthase domain protein from a hyperthermophilic archaeon. J Mol Biol 380:181–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boutz DR, Cascio D, Whitelegge J, Perry LJ, Yeates TO. 2007. Discovery of a thermophilic protein complex stabilized by topologically interlinked chains. J Mol Biol 368:1332–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mallick P, Boutz DR, Eisenberg D, Yeates TO. 2002. Genomic evidence that the intracellular proteins of archaeal microbes contain disulfide bonds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:9679–9684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142310499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jorda J, Yeates TO. 2011. Widespread disulfide bonding in proteins from thermophilic archaea. Archaea 2011:409156. doi: 10.1155/2011/409156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beeby M, O'Connor BD, Ryttersgaard C, Boutz DR, Perry LJ, Yeates TO. 2005. The genomics of disulfide bonding and protein stabilization in thermophiles. PLoS Biol 3:e309. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pedone E, Limauro D, D'Alterio R, Rossi M, Bartolucci S. 2006. Characterization of a multifunctional protein disulfide oxidoreductase from Sulfolobus solfataricus. FEBS J 273:5407–5420. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2006.05533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pedone E, Limauro D, D'Ambrosio K, De Simone G, Bartolucci S. 2010. Multiple catalytically active thioredoxin folds: a winning strategy for many functions. Cell Mol Life Sci 67:3797–3814. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0449-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Appleby TC, Mathews II, Porcelli M, Cacciapuoti G, Ealick SE. 2001. Three-dimensional structure of a hyperthermophilic 5′-deoxy-5′-methylthioadenosine phosphorylase from Sulfolobus solfataricus. J Biol Chem 276:39232–39242. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105694200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cacciapuoti G, Porcelli M, Bertoldo C, De Rosa M, Zappia V. 1994. Purification and characterization of extremely thermophilic and thermostable 5′-methylthioadenosine phosphorylase from the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. Purine nucleoside phosphorylase activity and evidence for intersubunit disulfide bonds. J Biol Chem 269:24762–24769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chu X, Yu W, Wu L, Liu X, Li N, Li D. 2007. Effect of a disulfide bond on mevalonate kinase. Biochim Biophys Acta 1774:1571–1581. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeDecker BS, O'Brien R, Fleming PJ, Geiger JH, Jackson SP, Sigler PB. 1996. The crystal structure of a hyperthermophilic archaeal TATA-box binding protein. J Mol Biol 264:1072–1084. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guelorget A, Roovers M, Guerineau V, Barbey C, Li X, Golinelli-Pimpaneau B. 2010. Insights into the hyperthermostability and unusual region-specificity of archaeal Pyrococcus abyssi tRNA m1A57/58 methyltransferase. Nucleic Acids Res 38:6206–6218. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hwa KY, Subramani B, Shen ST, Lee YM. 2014. An intermolecular disulfide bond is required for thermostability and thermoactivity of β-glycosidase from Thermococcus kodakarensis KOD1. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 98:7825–7836. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5731-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singleton M, Isupov M, Littlechild J. 1999. X-ray structure of pyrrolidone carboxyl peptidase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus litoralis. Structure 7:237–244. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(99)80034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang Y, Nock S, Nesper M, Sprinzl M, Sigler PB. 1996. Structure and importance of the dimerization domain in elongation factor Ts from Thermus thermophilus. Biochemistry 35:10269–10278. doi: 10.1021/bi960918w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feese MD, Kato Y, Tamada T, Kato M, Komeda T, Miura Y, Hirose M, Hondo K, Kobayashi K, Kuroki R. 2000. Crystal structure of glycosyltrehalose trehalohydrolase from the hyperthermophilic archaeum Sulfolobus solfataricus. J Mol Biol 301:451–464. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hopfner KP, Eichinger A, Engh RA, Laue F, Ankenbauer W, Huber R, Angerer B. 1999. Crystal structure of a thermostable type B DNA polymerase from Thermococcus gorgonarius. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96:3600–3605. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heinemann J, Hamerly T, Maaty WS, Movahed N, Steffens JD, Reeves BD, Hilmer JK, Therien J, Grieco PA, Peters JW, Bothner B. 2014. Expanding the paradigm of thiol redox in the thermophilic root of life. Biochim Biophys Acta 1840:80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishimura H, Azami Y, Miyagawa M, Hashimoto C, Yoshimura T, Hemmi H. 2013. Biochemical evidence supporting the presence of the classical mevalonate pathway in the thermoacidophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. J Biochem 153:415–420. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvt006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuzuyama T, Hemmi H, Takahashi S. 2010. Mevalonate pathway in Bacteria and Archaea, p 493–516. In Mander L, Liu H-W (ed), Comprehensive natural products. II. Chemistry and biology, vol 1 Elsevier, Oxford, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miziorko HM. 2011. Enzymes of the mevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis. Arch Biochem Biophys 505:131–143. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lombard J, Moreira D. 2011. Origins and early evolution of the mevalonate pathway of isoprenoid biosynthesis in the three domains of life. Mol Biol Evol 28:87–99. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsumi R, Atomi H, Driessen AJ, van der Oost J. 2011. Isoprenoid biosynthesis in Archaea—biochemical and evolutionary implications. Res Microbiol 162:39–52. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonanno JB, Edo C, Eswar N, Pieper U, Romanowski MJ, Ilyin V, Gerchman SE, Kycia H, Studier FW, Sali A, Burley SK. 2001. Structural genomics of enzymes involved in sterol/isoprenoid biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:12896–12901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181466998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Byres E, Alphey MS, Smith TK, Hunter WN. 2007. Crystal structures of Trypanosoma brucei and Staphylococcus aureus mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase inform on the determinants of specificity and reactivity. J Mol Biol 371:540–553. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Voynova NE, Fu Z, Battaile KP, Herdendorf TJ, Kim JJ, Miziorko HM. 2008. Human mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase: characterization, investigation of the mevalonate diphosphate binding site, and crystal structure. Arch Biochem Biophys 480:58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barta ML, McWhorter WJ, Miziorko HM, Geisbrecht BV. 2012. Structural basis for nucleotide binding and reaction catalysis in mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase. Biochemistry 51:5611–5621. doi: 10.1021/bi300591x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barta ML, Skaff DA, McWhorter WJ, Herdendorf TJ, Miziorko HM, Geisbrecht BV. 2011. Crystal structures of Staphylococcus epidermidis mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase bound to inhibitory analogs reveal new insight into substrate binding and catalysis. J Biol Chem 286:23900–23910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.242016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krepkiy D, Miziorko HM. 2004. Identification of active site residues in mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase: implications for a family of phosphotransferases. Protein Sci 13:1875–1881. doi: 10.1110/ps.04725204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cordier H, Karst F, Berges T. 1999. Heterologous expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae of an Arabidopsis thaliana cDNA encoding mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase. Plant Mol Biol 39:953–967. doi: 10.1023/A:1006181720100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alvear M, Jabalquinto AM, Eyzaguirre J, Cardemil E. 1982. Purification and characterization of avian liver mevalonate-5-pyrophosphate decarboxylase. Biochemistry 21:4646–4650. doi: 10.1021/bi00262a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cordier H, Lacombe C, Karst F, Berges T. 1999. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase (erg19p) forms homodimers in vivo, and a single substitution in a structurally conserved region impairs dimerization. Curr Microbiol 38:290–294. doi: 10.1007/PL00006804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berges T, Guyonnet D, Karst F. 1997. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase is essential for viability, and a single Leu-to-Pro mutation in a conserved sequence leads to thermosensitivity. J Bacteriol 179:4664–4670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bradford MM. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Collaborative Computational Project Number 4. 1994. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leslie AG. 2006. The integration of macromolecular diffraction data. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 62:48–57. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905039107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Evans P. 2006. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 62:72–82. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905036693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Long F, Vagin AA, Young P, Murshudov GN. 2008. BALBES: a molecular-replacement pipeline. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 64:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444907050172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Langer G, Cohen SX, Lamzin VS, Perrakis A. 2008. Automated macromolecular model building for X-ray crystallography using ARP/wARP version 7. Nat Protoc 3:1171–1179. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. 2010. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murshudov GN, Skubak P, Lebedev AA, Pannu NS, Steiner RA, Nicholls RA, Winn MD, Long F, Vagin AA. 2011. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 67:355–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krissinel E, Henrick K. 2004. Secondary-structure matching (SSM), a new tool for fast protein structure alignment in three dimensions. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60:2256–2268. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904026460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kabsch W, Sander C. 1983. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers 22:2577–2637. doi: 10.1002/bip.360221211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Svergun D, Barberato C, Koch MHJ. 1995. CRYSOL—a program to evaluate X-ray solution scattering of biological macromolecules from atomic coordinates. J Appl Crystallogr 28:768–773. doi: 10.1107/S0021889895007047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Read RJ, Adams PD, Arendall WB III, Brunger AT, Emsley P, Joosten RP, Kleywegt GJ, Krissinel EB, Lutteke T, Otwinowski Z, Perrakis A, Richardson JS, Sheffler WH, Smith JL, Tickle IJ, Vriend G, Zwart PH. 2011. A new generation of crystallographic validation tools for the Protein Data Bank. Structure 19:1395–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Krissinel E, Henrick K. 2007. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol 372:774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zillig W, Stetter KO, Wunderl S, Schulz W, Priess H, Scholz I. 1980. The Sulfolobus-Caldariella group—taxonomy on the basis of the structure of DNA-dependent RNA-polymerases. Arch Microbiol 125:259–269. doi: 10.1007/BF00446886. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grochowski LL, Xu H, White RH. 2006. Methanocaldococcus jannaschii uses a modified mevalonate pathway for biosynthesis of isopentenyl diphosphate. J Bacteriol 188:3192–3198. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.9.3192-3198.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smit A, Mushegian A. 2000. Biosynthesis of isoprenoids via mevalonate in Archaea: the lost pathway. Genome Res 10:1468–1484. doi: 10.1101/gr.145600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vannice JC, Skaff DA, Keightley A, Addo J, Wyckoff GJ, Miziorko HM. 2014. Identification in Haloferax volcanii of phosphomevalonate decarboxylase and isopentenyl phosphate kinase as catalysts of the terminal enzymatic reactions in an archaeal alternate mevalonate pathway. J Bacteriol 196:1055–1063. doi: 10.1128/JB.01230-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Azami Y, Hattori A, Nishimura H, Kawaide H, Yoshimura T, Hemmi H. 2014. (R)-Mevalonate 3-phosphate is an intermediate of the mevalonate pathway in Thermoplasma acidophilum. J Biol Chem 289:15957–15967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.562686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vinokur JM, Korman TP, Cao Z, Bowie JU. 2014. Evidence of a novel mevalonate pathway in archaea. Biochemistry 53:4161–4168. doi: 10.1021/bi500566q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vinokur JM, Korman TP, Sawaya MR, Collazo M, Cascio D, Bowie JU. 2015. Structural analysis of mevalonate-3-kinase provides insight into the mechanisms of isoprenoid pathway decarboxylases. Protein Sci 24:212–220. doi: 10.1002/pro.2607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]